Abstract

BACKGROUND

Youths perinatally infected with HIV often receive psychotropic medication and behavioral treatment for emotional and behavioral symptoms. We describe patterns of intervention for HIV-positive youth and youth in a control group in the United States.

METHODS

Three hundred nineteen HIV-positive youth and 256 controls, aged 6 to 17 years, enrolled in the International Maternal Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials 1055, a prospective, 2-year observational study of psychiatric symptoms. One hundred seventy-four youth in the control group were perinatally exposed to HIV, and 82 youth were uninfected children living in households with HIV-positive members. Youth and their primary caregivers completed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-referenced symptom-rating scales. Children's medication and behavioral psychiatric intervention histories were collected at entry. We evaluated the association of past or current psychiatric treatment with HIV status, baseline symptoms, and impairment by using multiple logistic regression, controlling for potential confounders.

RESULTS

HIV-positive youth and youth in the control group had a similar prevalence of psychiatric symptoms (61%) and impairment (14% to 15%). One hundred four (18%) participants received psychotropic medications (stimulants [14%], antidepressants [6%], and neuroleptic agents [4%]), and 127 (22%) received behavioral treatment. More HIV-positive youth than youth in the control group received psychotropic medication (23% vs 12%) and behavioral treatment (27% vs 17%). After adjusting for symptom class and confounders, HIV-positive children had twice the odds of children in the control group of having received stimulants and >4 times the odds of having received antidepressants. Caregiver-reported symptoms or impairment were associated with higher odds of intervention than reports by children alone.

CONCLUSIONS

HIV-positive children are more likely to receive mental health interventions than control-group children. Pediatricians and caregivers should consider available mental health treatment options for all children living in families affected by HIV.

Keywords: HIV, psychiatric disorders, treatment

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT.

HIV-positive youth have and are treated for psychiatric conditions, which occur at relatively high rates. Earlier studies were based on small samples or carried out early in the pediatric HIV epidemic.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS.

We document psychiatric treatment rates in a representative sample of HIV-positive children and controls. We found that HIV-positive youth had higher rates of past treatment than controls (both medical and behavioral) but similar rates of current medical treatment.

Youth with pediatric HIV infection have a high rate of psychiatric symptoms, particularly attention and depression1–10 for which they often receive pharmacological or behavior treatment.9–13 Yet, there is little literature on the patterns and efficacy of such treatment. Previous studies were based on small or nonrepresentative samples or were conducted early in the HIV pediatric epidemic, when children were more severely affected by comorbid infectious and noninfectious complications.14,15 Complex antiretroviral regimens, such as those taken by most HIV-positive children today, may affect adherence to psychiatric medication regimens as well as potentially interfere with drug metabolism.

In this study, we describe and compare psychotropic drug therapy and behavioral treatment patterns in 2 cohorts, perinatally HIV-infected children and a control group comprising both perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected children and HIV-uninfected children living in families affected by HIV. In our analyses, we adjust for entry characteristics that have been shown to affect access to and choice of care in low income families, specifically, age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity.16–19

METHODS

Participants

The International Maternal Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) group 1055 is a prospective, multisite, 2-year observational study of psychiatric symptoms in HIV-infected and uninfected children. It was designed to enroll similar numbers of HIV-infected and control subjects within each of the 4 age (<12 or ≥12 years) and gender subgroups across the 29 research sites. Youth must have lived with the same primary caregiver for at least 12 months before entry; youth with known mental retardation (IQ < 70 or special-education evaluations) were excluded from the study. From June 2005 through September 2006, the study enrolled 582 youth aged 6 to 17 years, 575 of whom met eligibility criteria (319 HIV-positive and 256 controls). Controls were either perinatally HIV-exposed and uninfected (PHE) or HIV-uninfected but living in a household with at least 1 HIV-infected person (LWH). At each visit, information about study participants and their families was gathered through interviews and self-completed instruments. Caregivers were asked about ~18 previous-year family life stressors (eg, loss of health insurance; separation, marriage, or divorce of the primary caregiver; death in the family). They also reported on their education, household income, and biological relationship to the study participant. Lifetime psychotropic and antiretroviral medication histories including start and stop dates were obtained through chart reviews and clinical interviews.

Participants could return to complete the interview within 90 days of initiation if more time was needed. Informants wrote their own answers on self-report instruments, but staff was available to read the questions to informants as needed. This study was approved by an institutional review board (IRB) at each of the 29 participating IMPAACT sites. Written informed consent was obtained from primary caregivers and assents were obtained from youth as allowed by local IRBs. Each participating site submitted a site implementation plan for how they would handle psychiatric referrals and unintended HIV disclosure, recruitment and retention, incentives, and quality control. Incentives varied according to site, were approved by the IRBs, and included, for example, coupons or small cash outlays to cover meals, transportation, parking, and noncash equivalents such as child care.

Psychiatric Treatments

Psychiatric medications were classified as stimulants, antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), neuroleptic agents, antihypertensive agents, and other medications. We evaluated both past medication history and current medication (children receiving medication at study entry). Caregivers also reported broadly on nonmedication treatment histories for the child's behavioral problems, including individual, family, and group counseling, behavior modification, after school tutoring, hospitalization, and dietary interventions.

Psychiatric Measures

Youth and their primary caregivers completed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) referenced rating scales for their children's psychiatric symptoms. The Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R (CASI-4R) is a 147-item, caregiver-completed, self-completed rating scale for evaluating youth 5 to 18 years of age; individual items correspond to DSM-IV symptoms and are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (never = 0, very often = 3).20 The CASI-4R is reliable and valid.21 The presence or absence of psychological conditions were determined by screening cutoff scores (meeting the number of symptoms defined by DSM-IV threshold criteria) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, including the inattentive, hyperactive, and combined types), generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive episode, dysthymia, somatization, separation anxiety, social phobia, bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and disturbing events or posttraumatic stress disorder. In addition, respondents were asked whether they had trouble functioning at school, at home, or in social situations because of symptoms. Any response of “often” or “very often” was classified as symptom-related impairment.

Youth self-reports were collected by 2 instruments, according to age group. The Youth's (Self-report) Inventory-4 (YI-4) is a 128-item, self-report rating scale for children and adolescents, ages 12 to 18 years, with items parallel to those in the CASI-4R. The YI-4 has satisfactory internal consistency (α = .66 –.87), test-retest reliability (r = 0.54 – 0.92), and convergent and discriminant validity.22,23 The YI-4 also includes impairment questions. The Child (Self-report) Inventory-4 contains 34 items parallel to the YI-4 for young children (8 – 11 years of age), focusing on 7 symptom areas: generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, social phobia, somatization, major depressive episode, dysthymia, and disturbing events.24 Younger children were not asked to assess impairment.

Statistical Analyses

Psychiatric conditions were defined to be present if the symptom cutoff score was met by either child or caregiver assessment. Clinically significant symptom-related impairment was defined if a child met both symptom cutoff and impairment (each reported by either caregiver or adolescent). We also separately analyzed caregiver-assessed and adolescent self-reported impairment scores.

HIV-infected and control-group characteristics, treatment experiences, and psychiatric symptom and impairment measures were compared by using Fisher's exact tests, Exact R × C tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and χ2 tests. The percentage of children receiving each type of mental health intervention was summarized for those with and without psychiatric conditions. We explored the relationship between the child's past and current treatment experience, HIV infection status, baseline psychiatric symptom status (assessed by caregiver or child), age at psychiatric assessment (<12 or ≥12 years), and gender by using multiple logistic regression analyses, controlling for the a priori potential confounders, socioeconomic class (caregiver education), and race/ethnicity. Pairwise and 3-way interactions between age, gender, and HIV status and between symptom report and HIV status were retained in the regression models if they met the criterion of P < .15. Each analysis focused on a different symptom class (psychiatric condition) and treatment modality (behavioral or medication, past or current, type of medication) pair. Logistic regression models were also used to evaluate the association between each type of mental health intervention and the child's psychological symptoms classified in 3 levels: not reported, child report alone, and caregiver-reported (with or without child self-report). The association of symptom-related impairment with mental health interventions was addressed by using logistic regression models for each type of intervention, first, by considering impairment as reported only by the caregiver and, second, as classified in 3 levels (no impairment reported, adolescent-reported, caregiver-reported). We also explored whether clinically significant symptom-related impairment (ie, both symptom and impairment reported by either child self-report or by caregiver assessment) predicted treatment. Additional analyses controlled for age in 2-year groups (6–7, 8–9, 10–11, 12–13, 14–15, and ≥16 years of age). In hypothesis testing, P values of <.05 were considered to be statistically significant. However, given the large number of models fit and predictors evaluated, the results are considered exploratory in nature, and particular attention in interpretation was paid to consistency across analyses. All analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.125 and are based on data submitted as of October 12, 2007.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants

HIV-infected subjects (n = 319) and controls (n = 256) were comparable by gender, race and ethnicity, experience with previous-year life stressors, and the proportion of caregivers self-reporting psychological symptoms. However, HIV-infected children were older than controls (62% ≥12 years of age versus 42%, respectively), less likely to live with biological parents (43% vs 76%, respectively), and more likely to live in households with higher socioeconomic status, as measured by household income and primary caregiver education. Of the controls, 174 (68%) were in the PHE subgroup and 82 were in the LWH subgroup; 96% of the PHE subgroup also lived with an HIV-positive person and >30% of both control subgroups lived with an HIV-positive sibling (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

P1055: Demographic Characteristics at Study Entry According to HIV Status and for HIV-Uninfected Subgroups

| HIV Status |

HIV+ vs Uninfected |

HIV-Uninfected Subgroup |

3-Group Comparison |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected (N = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (N = 256) | P | Perinatally HIV-Exposed (N = 174) | Living With HIV+ Person (N = 82) | P | |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 163 (51) | 122 (48) | .45a | 80 (46) | 42 (51) | .52a |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic, Asian, or other race | 44 (14) | 39 (15) | .03b | 25 (14) | 14 (17) | .007b |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 173 (54) | 111 (43) | 86 (49) | 25 (31) | ||

| Hispanic (regardless of race) | 102 (32) | 106 (41) | 63 (36) | 43 (52) | ||

| Age group at entry visit | ||||||

| Median | 13.12 | 11.26 | <.001c | 10.2 | 13.4 | <.001c |

| ≥12 y, n (%) | 200 (63) | 134 (43) | 56 (32) | 53 (65) | ||

| Caregiver is biological parent, n (%) | 134 (43) | 192 (76) | <.001a | 135 (80) | 57 (70) | <.001a |

| Family composition—participant lives with, n (%) | ||||||

| Another HIV+ person | 223 (70) | 248 (97) | <.001a | 166 (96) | 82 (100) | <.001a |

| HIV+ biological mother | 167 (52) | 188 (74) | <.001a | 141 (82) | 47 (57) | <.001a |

| HIV+ parentd | 186 (58) | 200 (78) | <.001a | 148 (86) | 52 (63) | <.001a |

| HIV+ siblingd | 54 (17) | 97 (38) | <.001a | 55 (32) | 42 (51) | <.001a |

| Life stressors | ||||||

| Median | 1.00 | 1.00 | .05c | 1.00 | 1.00 | <.001c |

| ≥1, n (%) | 199 (64) | 178 (69) | 108 (64) | 65 (79) | ||

| Caregiver met at least 1 psychiatric symptom cutoff, n (%) | 37 (12) | 38 (15) | .26a | 21 (13) | 17 (21) | .09a |

| Household income ≤20 000, n (%) | 133 (48) | 155 (66) | <.001a | 101 (64) | 54 (69) | <.001a |

| Caregiver completed high school, n (%) | 219 (70) | 152 (61) | .02a | 99 (59) | 53 (65) | .04a |

Four HIV-infected children and 5 controls had missing data on caregiver relationship; 6 of each group had missing data on life stressors; 7 HIV-infected children and 9 controls had missing data on caregiver psychiatric symptoms; 41 HIV-infected children and 20 controls had missing data on household income; 7 HIV-infected children and 5 controls had missing data on caregiver education; 1 HIV-infected child had missing entry RNA data. One control was missing household composition variables. One PHE control was missing family composition data.

Fisher's exact test.

Pearson's χ2 test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Biological or nonbiological relation.

The PHE and LWH control subgroups were comparable in gender, whether caregivers were biological parents, reported emotional problems, education, and income.

However, the subgroups differed in age (LWH median age: 13 years, similar to the HIV-positive group, versus PHE: 10 years of age) and race/ethnicity. Of the 3 study subgroups, more families of LWH children (79%) had previous-year life stressors compared with either HIV-positive or PHE children (64% each; P < .001). Also, more LWH children had caregivers who met psychiatric cutoffs (21%) compared to 12%–13% for the HIV-positive and PHE groups (P = .09; Table 1).

At study entry, 81% of the HIV-infected youth were taking highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), defined as ≥3 antiretroviral medications from ≥2 classes, whereas only 8% were not taking antiretroviral medications. Approximately one quarter (23%) was defined as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention class C, almost 75% had CD4% values of ≥25%, and almost 60% had undetectable HIV RNA levels at study entry (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

HIV Disease Characteristics

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| CDC HIV clinical class | |

| N: not symptomatic | 38 (12) |

| A: mildly symptomatic | 96 (30) |

| B: moderately symptomatic | 112 (35) |

| C: severely symptomatic | 73 (23) |

| Entry CD4% | |

| Median | 31.00 |

| 0%–14% | 22 (7) |

| 15%–24% | 62 (19) |

| 25%–34% | 122 (38) |

| ≥35% | 113 (35) |

| Entry HIV RNA copies | |

| Median | 400.00 |

| 0–400 | 189 (59) |

| 401–5000 | 49 (15) |

| 5001–10 000 | 15 (5) |

| 10 001–100 000 | 49 (15) |

| >100 000 | 16 (5) |

HIV-infected participants (N = 319). CDC indicates Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Psychiatric Symptoms and Impairment

Perinatally HIV-infected and control youth had a similar prevalence of psychiatric symptoms (61% of each group had at least 1 condition). Similar percents across groups (14%–18%) reported impairment or clinically significant impairment in at least 1 condition (Table 3). However, LWH controls reported more conduct disorder problems (7.5%) than either HIV-positive or PHE controls (each ~1%, 3-way unadjusted comparison; P = .006).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of Selected Psychiatric Conditions and Impairment According to HIV Infection Status and Perinatal HIV-Exposure Status for Controls

| Screening Prevalence (Assessed by Child or Caregiver), n (%)a |

Impairment (Assessed by Caregiver), n (%)b |

Impairment and Screening Prevalence (Assessed by Child or Caregiver), n (%) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-lnfected (n = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (n = 256) | Pc | HIV-lnfected (n = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (n = 256) | Pc | HIV-lnfected (n = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (n = 256) | Pc | HIV-Uninfected |

Pd | ||

| PHE (n = 174) | LWH (n = 82) | |||||||||||

| Any problems | 194 (61) | 155 (61) | >.999 | 46 (15) | 35 (14) | .90 | 55 (17) | 42 (17) | .91 | 27 (16) | 15 (18) | .84 |

| ADHD | 56 (18) | 42 (17) | .82 | 38 (12) | 28 (11) | .79 | 37 (12) | 28 (11) | .90 | 19 (11) | 9 (11) | 1.0 |

| Aggression | 45 (14) | 41 (16) | .48 | 19 (6) | 17 (7) | .73 | 20 (6) | 19 (8) | .62 | 10 (6) | 9 (11) | .28 |

| Mood | 55 (17) | 51 (20) | .39 | 4 (1) | 7 (3) | .23 | 9 (3) | 11 (4) | .37 | 8 (5) | 3 (4) | .57 |

| Anxiety | 119 (37) | 111 (44) | .12 | 17 (5) | 12 (5) | .85 | 9 (3) | 11 (4) | .37 | 7 (4) | 4 (5) | .48 |

Any problems: include mood, anxiety, ADHD, and aggression; ADHD: includes inattentive, hyperactive, and combined types; aggression: includes oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder; mood disorders: includes major depressive episode, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia; anxiety: includes generalized anxiety, separation anxiety.

For screening cutoffs, any problems also includes disturbing events (posttraumatic stress disorder). Anxiety also includes somatization and social phobia.

For impairment, anxiety also includes social phobia (caregiver assessment only).

Fisher's exact test.

Exact test, 3-group comparison, HIV-positive, PHE, and LWH.

Psychiatric Interventions

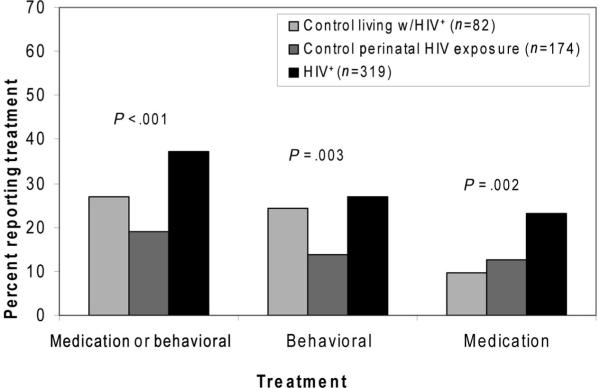

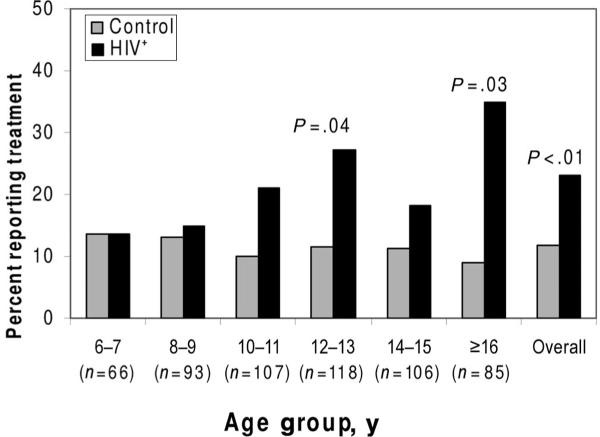

Children with HIV were more likely than controls to have received psychotropic medications and behavioral interventions, but the latter result varied by control subgroup (Fig 1). For example, 12% of controls and 23% of HIV-positive children had received psychiatric medication before study entry (P < .001; Table 4), a trend that held across age categories (for children ≥10 years of age; Fig 2) and medication classes (SSRIs, stimulants; data not shown). SSRIs were primarily given to adolescents (≥12 years of age), whereas stimulants were given across all age groups (data not shown). For behavioral interventions, the LWH subgroup reported as high a rate (24%) as the HIV-positive group (27%), both higher than for the PHE subgroup (14%, 3-way comparison; P = .003; Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

Percent of HIV-infected and uninfected participants who received treatment for emotional and behavioral problems.

TABLE 4.

P1055: Psychiatric Interventions According to HIV Status and Control Subgroup

| HIV Infection Status, n (%) |

HIV+ vs Control |

HIV-Uninfected, n (%) |

3-Group Comparison |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected (n = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (n = 256) | Pa | Perinatally HIV-Exposed (n = 174) | Living With HIV+ Person (n = 82) | Pb | |

| Past or current interventions | ||||||

| Medication or behavioral | 116 (37) | 54 (22) | <.001 | 32 (19) | 22 (27) | <.001 |

| Behavioral | 84 (27) | 43 (17) | .01 | 23 (14) | 20 (24) | .003 |

| Psychiatric medication | 74 (23) | 30 (12) | <.001 | 22 (13) | 8 (10) | .002 |

| ≥2 targeted medication classes | 21 (7) | 7 (3) | .049 | 4 (2) | 3 (4) | .10 |

| Stimulants | 54 (17) | 25 (10) | .01 | 18 (10) | 7 (9) | .05 |

| SSRIs | 30 (9) | 5 (2) | <.001 | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | <.001 |

| Neuroleptic agents | 14 (4) | 7 (3) | .37 | 4 (2) | 3 (4) | .57 |

| Antihypertensive agents | 6 (2) | 1 (0) | .14 | 1 (1) | 0 | .36 |

| Other psychiatric drugs | 6 (2) | 5 (2) | 1.00 | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | .91 |

| Current interventions | ||||||

| Psychiatric medicationc | 43 (13) | 25 (10) | .19 | 18 (10) | 7 (9) | .38 |

Missing observations: 6 each for controls and HIV-infected children for any past or current treatment; 6 for controls and 8 for HIV-infected children for past or current behavioral treatment.

Fisher's exact test.

Exact test, 3-group comparison among perinatally HIV-exposed controls, controls living with HIV-positive persons, and HIV-positive children.

Children currently receiving medication at study entry.

FIGURE 2.

Percent of HIV-positive (n = 319) and control (n = 256) children who were treated in the past or currently with medication for emotional and behavioral problems by 2-year age groups and overall. P values are shown if they are <.05.

Of the 104 participants who ever took a psychotropic agent, 90% had taken 1 or 2 drugs in a regimen, and only 21% had lifetime experience with >2 drugs. Medications taken by at least 5 children included: methylphenidate (n = 59), amphetamine salts (n = 32), atomoxetine (n = 13), risperidone (n = 13), sertra-line (n = 12), fluoxetine (n = 12), and bupropion (n = 6). Thirteen percent of the 292 HIV-infected children who were on antiretroviral medications at study entry were simultaneously taking psychotropic medications.

Rates of specific behavioral interventions were comparable for the HIV-infected and control groups, ranging from <15% (special diets, hospitalization), 30% to 50% (tutoring, group counseling, behavior modification, family counseling), to >80% (individual counseling) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Behavioral Interventions by Study Group

| HIV Infection Status, n (%) |

Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-lnfected (n = 319) | HIV-Uninfected (n = 256) | ||

| Past or current behavioral intervention | 84 (27) | 43 (17) | .01 |

| Individual counselingb | 69 (83) | 39 (91) | .29 |

| Family counselingb | 39 (47) | 22 (56) | .44 |

| Behavior modificationb | 26 (33) | 15 (43) | .30 |

| Group counselingb | 30 (36) | 11 (29) | .42 |

| After school tutoringb | 31 (38) | 11 (29) | .41 |

| Hospitalizationb | 11 (14) | 1 (3) | .10 |

| Special dietb | 9 (11) | 1 (3) | .17 |

Missing observations: 6 for controls and 8 for HIV-infected children for past or current behavioral treatment.

Fisher's exact test.

Percentages are of those children receiving any behavioral treatment.

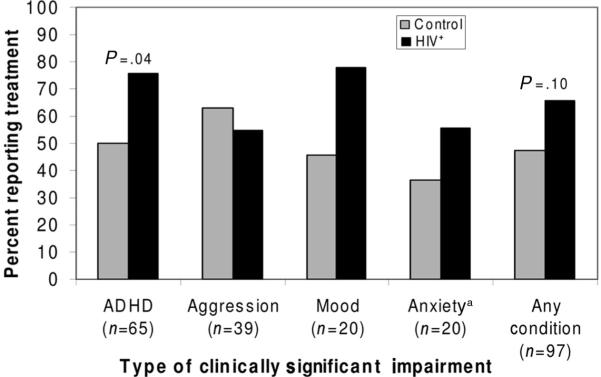

Treatment Stratified According to Psychiatric Condition

More HIV-positive children with clinically significant ADHD (76% of 37) received treatment compared with controls (50% of 28; P = .04; Fig 3). For the 3-way subgroup comparisons, among those with clinically significant impairment (HIV-positive group [n = 55], PHE group [n = 27], and LWH group [n = 15]), there were no differences in the percentages reporting lifetime psychiatric medication use (PHE group: 37%, LWH group: 20%, HIV-positive group: 40%; P = .41). However, fewer PHE controls with impairment still reported behavioral treatment (30%) than either the HIV-positive (57%) or LWH controls (60%; P = .05).

FIGURE 3.

Percent of HIV-positive and control children with clinically significant impairment who received behavioral or medication treatment. aSeparation or general anxiety. P values < .10 are shown for unadjusted comparison.

Predictors of Behavioral Interventions and Treatment With Psychiatric Medication

After controlling for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and caregiver education, perinatally HIV-infected youth had 4 to 13 times the odds of having treatment with antidepressant medication compared with controls, depending on the analysis (odds ratio [OR]: 3.9, any symptoms; OR: 4.3, ADHD; OR: 13.1, aggression; OR: 7.4, mood disorders; OR: 4.4, anxiety; Table 6). HIV-infected children also had higher odds than controls of having been treated with stimulants; after adjusting for ADHD symptoms (OR: 2.5), aggression (OR: 2.4), or mood disorders (OR: 2.1). The association between HIV-positive status and increased odds of intervention also held when age was controlled for in fine-grained categories (Fig 2 shows unadjusted data). The effect of HIV status on treatment sometimes was moderated by other factors. For example, within the younger ADHD-symptomatic group, HIV-infected children had half the odds as controls of having received medications, a result that countered the general trend (Table 6; interaction data not shown).

TABLE 6.

Adjusted ORs for Psychiatric Interventions Associated With Psychiatric Symptom Cutoffs

| Intervention and Psychiatric Condition |

Adjusted OR/(95% CI) for Interventiona |

Adjusted OR/(95% CI) for Intervention Based on Who Reported the Symptoma,b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ vs Control | Adolescent vs Younger Child (<12 y) | Symptom Cutoff vs None | HIV+ vs Control | Symptom Reported by Caregiver vs Child Only | |

| Ever received behavioral intervention | |||||

| Symptom cutoff | |||||

| Any condition | NS | 2.2 (1.2, 4.2) | NS | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.1) |

| ADHD | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.6) | 4.8 (2.2, 10.3) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.4) | NS |

| Aggression | 2.0 (1.2, 3.5) | NS | 7.9 (3.6, 17.4) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.4) | NS |

| Mood | 1.6 (1.0, 2.8) | 2.7 (1.4, 5.3) | 3.3 (1.6, 7.0) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | 8.9 (1.5, 50.8) |

| Anxiety | NS | 2.2 (1.1, 4.2) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.0) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.5) | NS |

| Ever received psychiatric medication Symptom cutoff | |||||

| Any condition | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1.6 (0.9, 2.9) |

| ADHD | NS | NS | 8.2 (3.5, 19.4) | 3.8 (1.8, 8.1) | NS |

| Aggression | NS | NS | 5.6 (2.3, 13.6) | 3.4 (1.6, 6.8) | NS |

| Mood | NS | NS | 2.9 (1.3, 6.7) | NS | 5.6 (1.4, 22.9) |

| Anxiety | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Ever received stimulants Symptom cutoff | |||||

| Any condition | NS | NS | NS | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | NS |

| ADHD | 2.5 (1.2, 5.0) | NS | 7.6 (3.1, 18.6) | 2.3 (1.0, 5.3) | 4.7 (1.1, 19.8) |

| Aggression | 2.4 (1.3, 4.7) | NS | 5.9 (2.4, 14.8) | 2.1 (1.0, 4.7) | NS |

| Mood | 2.1 (1.1, 3.9) | NS | 3.4 (1.4, 8.3) | 1.7 (1.0, 3.0) | 4.3 (1.1, 17.2) |

| Anxiety | NS | NS | NS | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) | NS |

| Ever received antidepressants Symptom cutoff | |||||

| Any condition | 3.9 (1.5, 10.5) | 4.9 (1.8, 13.0) | 2.6 (1.1, 6.1) | 3.9 (1.4, 10.5) | 3.4 (1.1, 10.5) |

| ADHD | 4.3 (1.6, 11.7) | 4.5 (1.7, 12.0) | 4.1 (1.9, 8.9) | 4.1 (1.3, 12.8) | 8.4 (1.0, 73.7) |

| Aggression | 13.1 (1.7, 99.3) | 3.8 (1.4, 10.2) | 18.1 (1.9, 170.4) | 4.0 (1.3, 12.3) | NS |

| Mood | 7.4 (1.7, 32.4) | 4.9 (1.8, 13.2) | 7.4 (1.2, 47.1) | 4.2 (1.5, 11.7) | 6.0 (0.9, 40.4) |

| Anxiety | 4.4 (1.3, 15.3) | 4.5 (1.7, 12.2) | NS | 3.8 (1.4, 10.1) | NS |

CLs indicates confidence limits; NS, not significant.

Adjusted in a logistic regression model for age group, gender, race/ethnicity, and caregiver education level. Psychiatric conditions were assessed by symptom cutoff score. ORs are shown if they were significant (P < .05) or marginally significant (P < .10).

Analyses of any symptom, mood (including major depressive episode, dysthymia, or bipolar symptoms), and anxiety (generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, social phobia, or somatization) included all children; ADHD (any type) and aggression (oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder) were based on adolescents (≥12 years of age) only.

Impairment As a Predictor of Treatment Intervention

The multivariable logistic regression analyses of associations between HIV status, impairment, and treatment outcomes supported the main results with only a few differences. For analyses of aggression and anxiety disorders, HIV-infected children with impairment had equal or lower odds of treatment than corresponding controls rather than higher ones (data not shown). For example, ~32% of controls with clinically significant aggression received stimulants compared with 10% of HIV-infected participants.

Caregiver Versus Child Self-Report and Age Effects

The odds of the child receiving treatment were more than twice as high when caregivers reported compared with when the child alone reported. For example, the odds of treatment were >4 times as high when caregivers compared with children reported mood disorder symptoms (Table 6). Our multivariable analysis also showed that adolescents had higher odds of behavioral interventions and antidepressant medication use compared with younger-aged children (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found more HIV-infected than control children (37% vs 22%) received behavior or medication interventions for emotional and behavioral problems. Although children from poor and minority families, similar to many of our study participants, are less likely to receive appropriate intervention for mental health concerns than their more affluent peers,16–19 low-income children with perinatally acquired HIV may be better connected to health care delivery systems compared with HIV-uninfected siblings.11 Another suggestive finding, although based on small numbers, was that, among control children with emotional problems, more PHE than LWH children received psychotropic medications. This could also be due to different treatment trajectories influenced by early health care contact because of their mother's HIV.

Although we found that perinatally HIV-infected participants had higher rates of lifetime psychotropic medication treatment compared with controls (23% vs 12%, respectively), the rates of current psychiatric medication use were comparable (13% vs 10%, respectively), results that held after adjusting for symptom status, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and caregiver education. We can infer that, similar to Medicaid-eligible youth,26 HIV-positive children may take psychiatric medications for short time periods, because almost twice as many of them reported experience with medication as were taking medications at study entry. Once prescribed, providers and/or caregivers may be reticent to continue administering psychotropic medications to HIV-positive youth.

We observed slightly higher psychotropic medication rates compared with overall rates reported by Gaughan et al10 and for ADHD9 but lower antidepressant and stimulant treatment rates than reported by Wiener et al.13 Still, we found slightly higher rates of current psychiatric medication intervention in the HIV-infected group than reported for the US Medicaid-eligible population.16 Because we controlled for caregiver education in our multivariable analyses as a marker of socioeconomic status, it is unlikely that the higher odds of treatment that we observed in the HIV-infected group relates to higher socioeconomic status, as reported for public-served youth.16,17,26,27 Instead, we may be observing a bias toward treatment for the chronically ill (HIV-positive) and against treatment for healthy (HIV-uninfected) children living with chronically ill family members. Many more of the control youth compared with the HIV-infected youth lived with HIV-infected parents (78% vs 58%) and with HIV-infected siblings (38% vs 17%), a finding that offers support for such an explanation.

We found no statistical differences between HIV-infected youth and controls in symptomatology or impairment, a finding consistent with those reported by Mellins et al7 in a study of children 3 to 8 years of age. Although unexpected, the lack of group difference may be partly attributable to in utero antiretroviral exposure or to family environment, including caregiver-child relationship, caregiver health, and life stressors. Fewer HIV-infected participants compared with controls (43% vs 76%, respectively) lived with biological parent caregivers, but more control parents were HIV-infected (see above), findings that suggest both groups had high levels of family stressors. Also, our data suggest that most of the controls were exposed to antiretroviral treatment in utero, whereas most of the HIV-infected children were not. We chose not to include caregiver relationship in our multivariate analyses, because we did not have a specific hypothesis as to how the relationship may have influenced treatment patterns, which was the primary focus of this study rather than the etiology of emotional problems in HIV-positive children.

Two other findings are consistent with current research. First, many of our participants received behavioral interventions; these strategies should continue to be assessed in the HIV-positive pediatric populations.12,28 Second, because children were less likely to receive treatment if the child alone indicated problems, children should be asked directly about their emotional problems.29,30

There were several limitations to this analysis. First, because the HIV-infected participants in our study were older than the controls, they had greater opportunity to have received treatment. To mitigate this problem, we controlled for age group in our logistic regression analyses. Second, our data suggest that LWH controls may have represented a more vulnerable population (as measured by more experience with life stressors and caregiver symptomatology), which conceivably could have led to different symptomatology and treatment experiences. We felt that the family composition data and similar symptom profiles justified pooling the 2 control subgroups for our main analysis. In our multivariable analyses, we also controlled for other entry characteristics (age, race/ethnicity) that differed between the 2 control subgroups. Future analyses can look into differential effects on treatment of other differences, for example, the impact of living with biological HIV-positive mothers.

CONCLUSIONS

We urge pediatricians who serve families affected by HIV to screen and refer for emotional and behavioral problems. More research is needed on effective service delivery patterns and on caregiver and youth decision-making regarding care-seeking. Because substantial proportions of HIV-infected youth who report emotional problems also receive psychotropic medications, research is also needed on potential drug-drug interactions and on adherence to both antiretroviral and psychotropic medication regimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Overall support for the IMPAACT group was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U01 AI068632), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institutes of Mental Health. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (5 U01 AI-41110) and with the IMPAACT group (1 U01 AI-068616).

We thank Kimberly Hudgens for operational support of this study and Janice Hodge for data management. In addition to their contributions to the manuscript, we acknowledge the help given by Nagamah Sandra Deygoo in representing the site research staff on the protocol team and Vinnie Di Paolo for representing the community affected by HIV.

The following institutions and individuals participated in IMPAACT P1055: 2901, HMS Children's Hospital Boston, Division of Infectious Diseases: Sandra Burchett; 3601, UCLA-Los Angeles/Brazil AIDS Consortium/Clinical Research Cite (CRS): Karin Nielsen, MD, Nicole Falgout, RN, Joseph Geffen, and Jaime G. Deville, MD, FAAP; 3606, Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, Miller Children's Hospital: Audra Deveikis; 3609, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases: Margaret Keller; 3702, University of Maryland Medical Center, Division of Pediatric Immunology and Rheumatology: Vicki Tepper; 4001, Chicago Children's CRS: Ram Yogev; 4501, UCSF Pediatric AIDS CRS: Diane Wara; 4601, UCSD Maternal, Child, and Adolescent HIV CRS: Stephen A. Spector, MD, Lisa Stangl, CPNP, Mary Caffery, RN, MSN, and Rolando Viani, MD, MTP; 4701, DUMC Pediatric CRS: Kreema Whitfield, Sunita Patil, PhD, Joan Wilson, RN, Mary Jo Hassett, RN; 5012, NYU NY Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) CRS: Sandra Deygoo, William Borkowsky, Sulachni Chandwani, and Mona Rigaud; 5013, Jacobi Medical Center Bronx NICHD CRS: Andrew Wiznia; 5017, University of Washington Children's Hospital Seattle NICHD CRS: Lisa Frenkel; 5018, USF Tampa NICHD CRS: Patricia Emmanuel, MD, Jorge Lujan Zilberman, MD, Carina Rodriguez, MD, and Carolyn Graisbery, RN; 5026, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY: Roberto Posada, MD, and Mary S. Dolan, RN; 5031, San Juan City Hospital PR NICHD CRS: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, MT, MD, Lourdes Angeli, BS, MPH, Milagros Gonzalez, MD, and Dalila Guzman, RPh; 5038, Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Disease: Warren A. Andiman, MD, Leslie Hurst, BS, and Anne Murphy, MSW; 5039, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Department of Pediatrics: Leonard Weiner; 5040, SUNY Stony Brook NICHD CRS: Denise Ferraro, RN, Michele Kelly, PNP, and Lorraine Rubino; 5044, Howard University Washington DC NICHD CRS: Sohail Rana; 5048, USC LA NICHD CRS: Suad Kapetanovic; 5051, University of Florida Jacksonville NICHD CRS: Mobeen H. Rathore, MD, Ayesha Mirza, MD, Kathleen Thoma, MA, and Chas Griggs; 5052, University of Colorado Denver NICHD CRS: Robin McEvoy, Emily Barr, Suzanne Paul, and Patricia Michalek; 5055, South Florida CDC Ft Lauderdale NICHD CRS: Ana Puga; 6501, St Jude/UTHSC CRS: Patricia Garvie; 6701, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia IMPAACT CRS: Richard Rutstein; 6704, St Christopher's Hospital for Children: Roberta LaGuerre; 6901, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital IMPAACT CRS: Murli Purswani; 6905, Metropolitan Hospital Center: Mahrukh Bamji; and 7301, WNE Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS CRS: Katherine Luzuriaga.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CASI-4R

Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral treatment

- IMPAACT

International Maternal Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials

- IRB

institutional review board

- LWH

HIV-uninfected but living in a household with at least 1 HIV-infected person

- OR

odds ratio

- PHE

perinatally HIV-exposed and uninfected

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- YI-4

Youth's Inventory-4

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

This work was presented in part at the 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 25–28, 2007; Los Angeles, CA; and the 68th annual meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology; March 25–29, 2008; Memphis, TN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertou G, Thomaidis L, Spoulou V, Theodoridou M. Cognitive and behavioral abilities of children with HIV infection in Greece [abstract] Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):S100. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Pao M. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam PK, Naar-King S, Wright K. Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(1):20–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nozyce ML, Lee SS, Wiznia A, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):763–770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeremy RJ, Kim S, Nozyce M, et al. Neuropsychological functioning and viral load in stable anti-retroviral therapy-experienced HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):380–387. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams EJ. Psychiatric disorders in youth with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(5):432–437. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000217372.10385.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellins CA, Smith R, O'Driscoll P, et al. High rates of behavioral problems in perinatally HIV-infected children are not linked to HIV disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):384–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharko AM. DSM psychiatric disorders in the context of pediatric HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18(5):441–445. doi: 10.1080/09540120500213487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutstein R, Josephs J, Guar A, et al. Mental health and special education issues in a cohort of HIV infected children: results from a multisite survey. Presented at: the 14th Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Los Angeles, CA. February 25–28, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaughan DM, Hughes MD, Oleske JM, Malee K, Gore CA, Nachman S. Psychiatric hospitalizations among children and youths with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e544. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/6/e544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donenberg GR, Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: psychiatry's role in a changing epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Wight RG, et al. Improving the quality of life among young people living with HIV. Eval Program Plann. 2001;24(2):227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiener L, Battles H, Ryder C, Pao M. Psychotropic medication use in human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth receiving treatment at a single institution. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(6):747–753. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nachman SA, Chernoff M, Gona P, et al. PACTG 219C Team. Incidence of noninfectious conditions in perinatally HIV-infected children and adolescents in the HAART era. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(2):164–171. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.163.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gona P, Van Dyke RB, Williams PL, et al. Incidence of opportunistic and other infections in HIV-infected children in the HAART era. JAMA. 2006;296(3):292–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zito JM, Safer DJ, Zuckerman IH, Gardner JF, Soeken K. Effect of medicaid eligibility category on racial disparities in the use of psychotropic medications among youths. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(2):157–163. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leslie LK, Weckerly J, Landsverk J, Hough RL, Hurlburt MS, Wood PA. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of psychotropic medication in children at high risk and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1433–1442. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000091506.46853.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costello EJ, Farmer EM, Angold A, Burns BJ, Erkanli A. Psychiatric disorders among American Indian and white youth in Appalachia: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):827–832. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiello AE, Simanek AM, Galea S. Population levels of psychological stress, herpesvirus reactivation and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9358-4. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-4R. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. The Symptom Inventories: An Annotated Bibliography. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Youth's Inventory-4 Manual. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson GA, et al. A DSM-IV-referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):671–679. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Self-report Inventory-4. Checkmate Plus; Stony Brook, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.SAS Software. Release 9.1. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2002. [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, et al. Utilization of pharmacologic treatment in youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Medicaid database. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(1):24–31. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zito JM, Tobi H, de Jong-van den Berg LT, et al. Antidepressant prevalence for youths: a multinational comparison. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(11):793–798. doi: 10.1002/pds.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Detels R, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Duan N. The effect of social support on mental and behavioral outcomes among adolescents with parents with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1820–1826. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauman LJ, Silver EJ, Draimin BH, Hudis J. Children of mothers with HIV/AIDS: unmet needs for mental health services. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2680. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/5/e1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford T, Sayal K, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Parental concerns about their child's emotions and behaviour and referral to specialist services: general population survey. BMJ. 2005;331(7530):1435–1436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7530.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]