Abstract

Aims

Previous studies showed that autonomic activation by high-frequency electrical stimulation (HFS) during myocardial refractoriness evokes rapid firing from pulmonary vein (PV) and atria, both in vitro and in vivo. This study sought to investigate the autonomic mechanism underlying the rapid firings at various sites by systematic ablation of multiple ganglionated plexi (GP).

Methods and results

In 43 mongrel dogs, rapid firing-mediated atrial fibrillation (AF) was induced by local HFS (200 Hz, impulse duration 0.1 ms, train duration 40 ms) to the PVs and atria during myocardial refractoriness. The main GP in the atrial fat pads or the ganglia along the ligament of Marshall (LOM) were then ablated. Ablation of the anterior right GP and inferior right GP significantly increased the AF threshold by HFS at the right atrium and PVs. The AF threshold at left atrium and PVs was significantly increased by ablation of the superior left GP and inferior left GP, and was further increased by ablation of the LOM. Ablation of left- or right-sided GP on the atria had a significant effect on contralateral PVs and atrium. Administration of esmolol (1 mg/kg) or atropine (1 mg) significantly increased AF threshold at all sites.

Conclusion

HFS applied to local atrial and PV sites initiated rapid firing via activation of the interactive autonomic network in the heart. GP in either left side or right side contributes to the rapid firings and AF originating from ipsolateral and contralateral PVs and atrium. Autonomic denervation suppresses or eliminates those rapid firings.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Ganglionated plexus, Autonomic nervous system

1. Introduction

It has been shown that most of the paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) is because of rapid firings originating from pulmonary veins (PVs) and non-PV sites.1,2 Previous investigations have focused on specific histological and electrophysiological properties of PVs. However, the results of numerous in vivo and in vitro studies on this subject have not conclusively defined a mechanism. Our prior studies3–8 suggested that some of the rapid PV firings can be induced and eliminated by stimulation and interruption of the intrinsic cardiac autonomic nervous system (ICANS). Clinical evidence also demonstrated that ablation of the main ganglionated plexi (GP) on the atria increases the success of the standard PV isolation by catheter ablation for AF.9 These studies underscore the important role of the ICANS in the formation of rapid firings coming from PV or non-PV sites.

Multiple anatomic studies10,11 have shown that the ICANS forms an interconnected neural network composed of multiple GP and the ligament of Marshall (LOM) with their associated axonal fields on the heart. Several GP within epicardial fat pads on the atria of mammalian hearts include: (i) the anterior right GP (ARGP) located at the right superior PV (RSPV)–atrial junction; (ii) the inferior right GP (IRGP) situated at the junction of inferior vein cava and both atria; (iii) the superior left GP (SLGP) located near the left superior PV (LSPV)–atrial junction and left pulmonary artery, and (iv) inferior left GP (ILGP) at the left inferior PV (LIPV)–atrial junction. Furthermore, recent studies12–15 demonstrated a cluster of autonomic ganglia along LOM. In a previous animal study,16 rapid firings from PV or non-PV sites were produced by local high-frequency electrical stimulation (HFS) of the neural elements during myocardial refractoriness, resembling findings in patients with focal AF. We hypothesized that rapid firing can be eliminated by ablation of the atrial GP. Using a similar model, we systematically investigated the neural mechanism underlying the rapid firing by ablation of the adjacent or distant GP.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal preparation

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). A total of 43 adult mongrel dogs weighing 20–25 kg were anaesthetized with Na-pentobarbital 50 mg/kg, and followed by additional dose of 2 mg/kg at the end of each hour. All dogs were ventilated with room air by a positive pressure respirator. Core body temperature was maintained at 36.5 ± 1.5°C. At the end of each study, animals were euthanized with a large dose of pentoparbital, followed by ventricular fibrillation induced by DC current. Standard ECG and blood pressure were continuously recorded, filtered at 0.1–250 Hz. All tracings from the electrode catheters were amplified and digitally recorded using a computer-based Bard Lab System (CR Bard Inc., Billerica, MA, USA), filtered at 30–500 Hz.

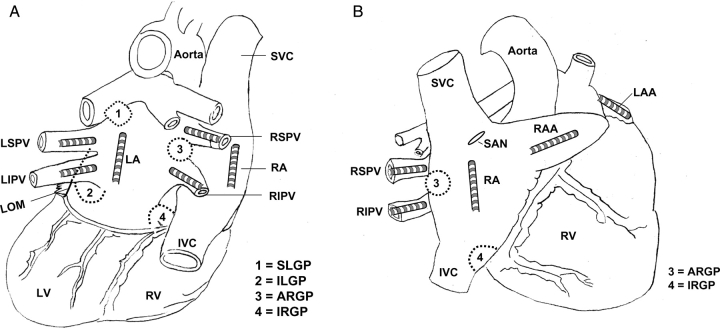

The chest was entered via a left or right thoracotomy at the fourth intercostal space.5–8 Multi-electrode catheters were sutured to multiple sites to allow recording and stimulation at the left atrial appendage (LAA), left atrium (LA), left superior PV (LSPV), and left inferior PV (LIPV) (Figure 1A). Similar electrode catheters were attached to right atrial appendage (RAA), right atrium (RA), right superior PV (RSPV), and right inferior PV (RIPV) (Figure 1B). Both cervical vagosympathetic trunks were dissected and a pair of Teflon-coated silver wires (0.1 mm diameter) was inserted into each of the vagosympathetic trunks for electrical stimulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation and catheter position. (A) Posterior–anterior view; (B) right anterior oblique view. Multi-electrode catheters were sutured to the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV), left inferior PV (LIPV), left atrium (LA), left atria appendage (LAA), right superior PV (RSPV), right inferior PV (RIPV), right atrium (RA), and right atrial appendage (RAA). ARGP, anterior right ganglionated plexi located adjacent to the RSPV–atrial junction; IRGP: inferior right GP, located at the junction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and both atria; SLGP: superior left GP, located adjacent to the LSPV and atrial junction; ILGP: inferior left GP located near the junction of LIPV and LA. LOM: ligament of Marshall; LV: left ventricle; RV: right ventricle.

2.2. Local high-frequency stimulation

HFS15,16 consisted of trains of high-frequency electrical stimuli (200 Hz, 0.1 ms in duration of each impulse, train duration 40 ms, 0.6–12 V) (S-88 Grass stimulator; Astro-Med, West Warwick, RI, USA). The voltages reported in this study are those delivered at the tip of the catheter, not the readings on the Grass stimulator. The local site where HFS was delivered was paced at 2× threshold (TH) at a rate of 182/min (330 ms). The trains of HFS were delivered at 2 ms after each pacing stimulus. The coupling interval (2 ms) was fixed so that the high-frequency train was delivered immediately after the onset of the paced local tissue excitation (within its refractory period) to ensure that the HFS only stimulated local neural elements, not the myocardium15,16 (Figure 2). The HFS was immediately discontinued if rapid activation was observed (Figure 3). According to a previous report,8 AF was defined as irregular atrial rates faster than 500 b.p.m. associated with irregular AV conduction lasting >5 s without HFS (Figure 3). The lowest HFS voltage at which AF was induced, i.e. AF threshold, was determined at the tip pair of electrode catheter positioned at each site before and after GP ablation. In rare cases, only focal firing could be induced at certain voltages but could not convert into AF after HFS stopped. The HFS was then kept for 5 s. If the focal firing could still not sustain, the voltages would be increased until AF was induced.

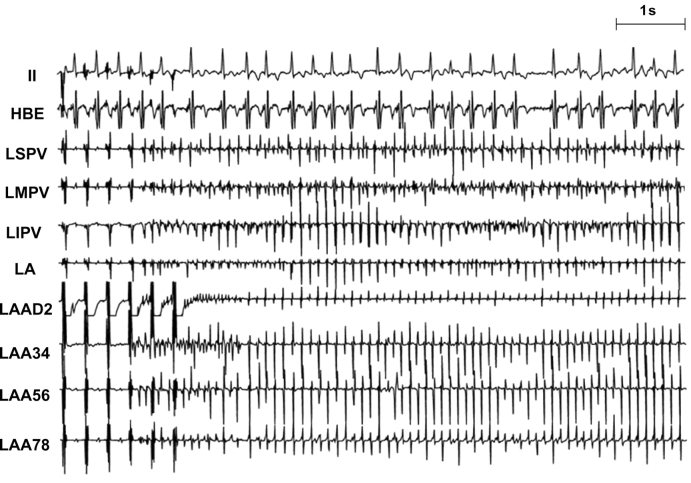

Figure 2.

An example of prolongation of A–H interval and slowing of the AV conduction during high-frequency stimulation (HFS). (A) Prolongation of A–H interval and 2:1 AV conduction block were induced by HFS (1.5 V) at the LSPV. (B) Significant slowing of AV conduction was induced by HFS (2.4 V) at LIPV during atrial fibrillation (AF). AV block was observed just before initiation of AF. HFS was intentionally not discontinued to show the slowing of AV conduction in the second half as shown in (B). Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

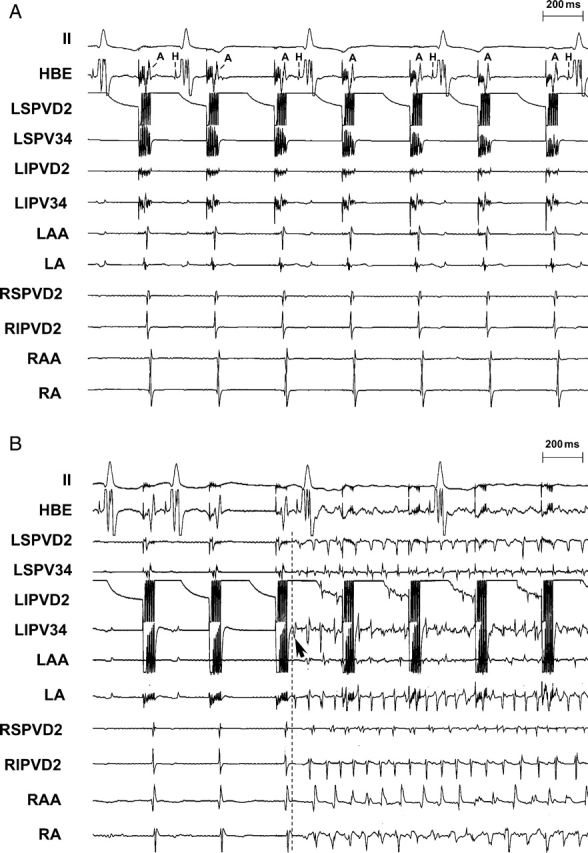

Figure 3.

An example of electrograms during AF initiated by HFS at the LAA. AF was defined as irregular atrial rates faster than 500 b.p.m. associated with irregular AV conduction lasting >5 s without HFS. Rapid firing and AF was induced by HFS at the LAA. Of note, left PVs replaced the LAA as the rapid firing site maintaining AF at the last part of the tracings, indicating that the autonomic nervous network was activated by HFS to the LAA. After ablation of the main atrial GP on both sides, AF could not be induced at the same site (LAA) at maximal voltage (12 V).

2.3. GP ablation

The ARGP located in the fat pad at the RSPV–atrial junction was identified by applying HFS (20 Hz, 0.1 ms duration, 0.6–4.5 V) with a bipolar stimulation/ablation probe electrode (AtriCure, West Chester, OH, USA).5–8 In this voltage range, progressive slowing of the heart rate (HR) was observed directly related to the voltage applied. The same device was later used to deliver radiofrequency current (460 kHz, ≤32.5 W) in order to ablate the ARGP. The IRGP, SLGP, ILGP, and autonomic ganglia along the LOM (Figure 1) were also identified and subsequently ablated using the same device.5–8 In all cases, radiofrequency current was delivered to the epicardial surface of the LOM and each GP. Complete ablation of each GP or autonomic ganglia along the LOM was verified by applying maximal strength of stimulation (12 V) that failed to slow the sinus rate or inhibit AV conduction.

2.4. Protocols

Group 1: Effects of ablation of ARGP+IRGP on AF threshold at ipsolateral and contralateral PVs and atrial sites. Ipsilateral sites included the RSPV, RIPV, RA, and RAA sites, whereas contralateral sites include LSPV, LIPV, LA, and LAA sites.

Group 2: Effects of ablation of SLGP+ILGP+LOM on AF threshold at ipsolateral and contralateral PVs and atrial sites. Contralateral sites included the RSPV, RIPV, RA, and RAA sites, whereas ipsilateral sites include LSPV, LIPV, LA, and LAA sites.

Group 3: Effects of a beta-blocker (esmolol, 1 mg/kg) or a muscarinic receptor blocker (atropine, 1 mg) intravenously, on AF threshold at the PVs and atrial sites.

Group 4: Effects of the extrinsic cardiac autonomic nervous system on AF threshold by HFS (200 Hz, 0.01 ms in the duration of each impulse, train duration 40 ms) at multiple PV and atrial sites. The AF threshold of HFS was measured with and without ipsilateral ceral vagosysmpathetic trunk stimulation (VTS) before and after GP ablation. The strength of VTS was set at the voltage required for slowing the HR by 50% or inducing 2:1 AV block. After GP (ARGP + IRGP + SLGP + ILGP + LOM) ablation, the measurements of AF threshold at the same VTS voltage as prior to ablation were repeated.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The median of AF thresholds (in volts) are presented along with the first quartile and the third quartile (Tables 1–4, within parentheses). The threshold level for AF inducibility before and after GP ablation or autonomic blockades administration or VTS at any given site were compared by non-parametric Wilcoxon-signed ranks test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Effects of ablation of ARGP and IRGP on the voltage threshold (volts) for AF inducibility at PVs and atria

| Ipsolateral |

Contralateral |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAA (n = 14) | RA (n = 10) | RSPV (n = 14) | RIPV (n = 14) | LAA (n = 7) | LA (n = 7) | LSPV (n = 7) | LIPV (n = 7) | |

| Before ARGP + IRGP ablation | 1.5 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.5; 4.5) | 2.4 (2.2; 6.5) | 3.2 (2.2; 7.5) | 1.5 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.5; 3.2) | 3.2 (3.2; 7) | 2.4 (1.5; 6) |

| After ARGP + IRGP ablation | 2.4 (2.2; 5.8) | 2.8 (2.2; 6.5) | >12a (9.6; >12 V) | >12 (11.3; >12) | 3.2 (1.5; >12) | 4.5 (1.5; >12) | 9.5 (4.5; >12) | 11.2 (3.2; >12) |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

Non-parametric Wilcoxon-signed ranks test was used for this analysis. The median of the AF thresholds was expressed as median (first quartile; third quartile). ARGP = anterior right ganglionated plexi; IRGP = inferior right ganglionated plexi; AF, atrial fibrillation; PV, pulmonary vein; RAA, right atrial appendage; RA, right atrium; RSPV, right superior PV; RIPV, right inferior PV; LAA, left atrial appendage; LA, left atrium; LSPV, left superior PV; LIPV, left inferior PV.

a>12 Indicates that AF could not be induced by maximal voltage (12 V).

Table 2.

Effects of ablation of SLGP and ILGP on the voltage threshold (volts) for AF inducibility at PVs and atria

| Ipsolateral |

Contralateral |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAA (n = 10) | LA (n = 6) | LSPV (n = 10) | LIPV (n = 10) | RAA (n = 10) | RA (n = 8) | RSPV (n = 10) | RIPV (n = 10) | |

| Before SLGP+ILGP ablation | 1.5 (1.5; 3.3) | 2.8 (2.2; 4.5) | 2.4 (2.2; 2.6) | 2.8 (2.2; 4.8) | 1.5 (1.5; 1.8) | 1.5 (1.4; 1.5) | 2.8 (1.5; 9) | 3.8 (2.2; 9) |

| After SLGP + ILGP ablation | 3.8 (2.2; 8) | 8.5 (4.5; 9.5) | 8 (3.2; 11.2) | 9.5 (3.2; >12) | 2.8 (1.9; 3.2) | 2.4 (1.8; 4.8) | 6.5 (4.5; 9.8) | 7 (4.5; 9.2) |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.01 | 0.2 |

SLGP, superior left ganglionated plexi; ILGP, inferior left ganglionated plexi. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Table 3.

Effects of ablation of autonomic ganglia along the LOM on the voltage threshold (volts) for AF inducibility at left PV and atrial sites

| LAA (n = 9) | LA (n = 6) | LSPV (n = 9) | LIPV (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After, SLGP + ILGP ablation | 3.2 (2; 9.3) | 8.5 (4.5; 9.5) | 8 (3.2; 9.6) | 9.6 (5.2; >12) |

| After SLGP + ILGP + LOM ablation | 8 (4; 11.6) | >12 (6.7; >12) | >12 (8; >12) | >12 (11; >12) |

| P-value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

LOM, ligament of Marshall.

Table 4.

Effects of autonomic blocker administration on the voltage threshold (volts) for AF inducibility at atria and PV

| LAA | LA | LSPV | LIPV | RAA | RA | RSPV | RIPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine (n = 5) | ||||||||

| Before | 2.4 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.5; 4) | 3.2 (1.5; 3.2) | 2.4 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.5; 2.6) | 2.4 (2; 6.5) | 4.5 (2.4; 9.3) |

| After | >12 | >12 | >12 | >12 | >12 | >12 | >12 | >12 |

| P-value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Esmolol (n = 7) | ||||||||

| Before | 1.5 (1.5; 2.4) | 1.5 (1.4; 2.4) | 3.2 (1.5; 6) | 3.2 (2.4; 4.5) | 1.5 (1.5; 2.4) | 2.4 (1.5; 4.5) | 3.2 (2.4; 3.2) | 3.2 (2.4; 8) |

| After | 4.5 (3.2; 6) | 4.5 (3.2; 6) | 6 (4.5; 9) | 8 (7; 10.4) | 4.5 (2.4; 6) | 6 (3.2; 7) | 6 (3.2; 6) | 6 (4.5; 9) |

| P-value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

3. Results

3.1. AF inducibility before GP ablation

The threshold for atrial pacing was 0.2 ± 0.05 V and was not altered by ablation. When HFS was applied to the neural elements during myocardial refractoriness at each site, prolongation of the A–H interval or slowing of the ventricular rate during AF was frequently observed, especially when HFS was delivered at the PVs. As shown in Figure 2, prolongation of A–H interval or 2:1 AV conduction block was induced by HFS (1.5 V) at the LSPV (Figure 2A). Significant slowing or block of AV conduction was also induced by HFS (2.4 V) at LIPV during AF (Figure 2B). In this example, AV block was observed just before initiation of AF. AF initiated by rapid firing was reliably induced by applying HFS during myocardial refractoriness at each atrial/PV site in all cases. As shown in Figures 2B (arrows) and 3 (LAA), rapid firing originated from where HFS was applied. The average cycle length of the first 10 beats of the rapid firing was 55 ± 15 ms. The average duration of AF was 8 ± 5 s.

3.2. AF inducibility after GP ablation

3.2.1. Group 1

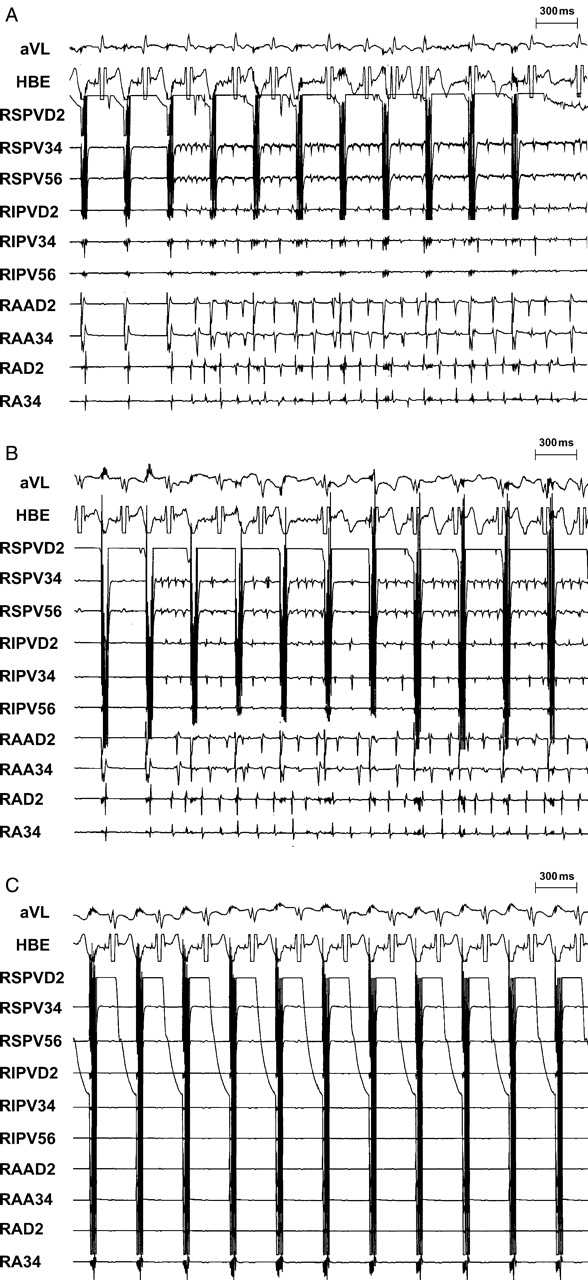

After ablation of ARGP and IRGP, AF threshold by HFS was significantly increased at RA, RAA, RSPV, and RIPV, ipsilateral to the ARGP and IRGP. AF could not be induced by HFS at maximal voltage (12 V) in 9 of 14 dogs at RSPV and 10 of 14 dogs at RIPV, and could still be induced in 13 of 14 dogs at the RAA and 10 of 10 dogs at the RA, but the increase in AF threshold was significant. The AF threshold at the contralateral sites (LAA, LA, LSPV, and LIPV) was also significantly elevated by ablation of ARGP and IRGP (Table 1).

3.2.2. Group 2

Ablation of SLGP and ILGP significantly increased the AF threshold at both ipsolateral (LAA, LA, LSPV, and LIPV) and contralateral sides (RAA, RA, and RSPV except RIPV) (Table 2). Subsequently, ablation of the autonomic ganglia along the LOM further increased the AF threshold at all left sites (Table 3). Of note, in six dogs after ablation of all major GP on the atria (ARGP + IRGP + SLGP + ILGP + LOM), AF could not be induced at any PV site at maximal voltage in all the six dogs and still could be induced at either atrium or atrial appendage in four of six dogs, but AF thresholds were significantly increased (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

An example of HFS at the RSPV before and after GP ablation. (A) Rapid firing-mediated AF was initiated by HFS (1.5 V) from RSPV; (B) after ablation of ipsolateral (right-sided) GP (ARGP + IRGP), the AF threshold at RSPV was increased to 9.3 V; (C) AF could not be induced at maximal voltage (12 V) after further ablation of contralateral (left-sided) GP (SLGP + ILGP + LOM).

3.2.3. Group 3

Administration of autonomic blockers, esmolol (1 mg/kg) significantly increased the AF threshold at all sites and atropine (1 mg) eliminated AF inducibility at all sites in each dog (Table 4).

3.3. Effects of extrinsic cardiac nervous system on AF inducibility

3.3.1. Group 4

Stimulation of vagosympathetic trunks at the voltage required for slowing the HR by 50% or inducing 2:1 AV block significantly decreased the AF threshold at all sites before GP (ARGP + IRGP + SLGP + ILGP + LOM) ablation. However, VTS at the same voltage as prior to GP ablation did not alter the AF threshold after GP ablation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of ipsilateral ceral vagosysmpathetic trunk stimulation (VTS) on AF inducibility by HFS before and after GP ablation (n = 7). Left VTS was denoted as ‘ipsilateral’ to the left PVs, atrium and atrial appendage while right VTS was denoted as ‘ipsolateral’ to the right PVs, atrium and atrial appendage. After GP (ARGP + IRGP + SLGP + ILGP + LOM) ablation, the measurements of AF threshold at the same VTS voltage as prior to ablation were repeated. The HFS for measurements of AF threshold was set at 200 Hz, 0.01 ms in duration of each impulse, train duration 40 ms, and was delivered within the myocardial refractoriness.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The present study showed that ablation of either left- or right-sided GP on the atria significantly increased the AF threshold by HFS at both the ipsolateral and contralateral PVs and atrium (Tables 1 and 2). Ablation of the neural elements in the LOM further elevated the AF threshold at the left sites (Table 3). Administration of autonomic blockers, esmolol, or atropine, significantly increased AF thresholds at all sites (Table 4). GP ablation prevented the decrease of AF threshold induced by stimulation of vagosympathetic trunks (Figure 5). These findings underscore the presumptive mechanism that the interconnected atrial autonomic network formed by the ICANS contributes to the formation of rapid firing from PV sites or non-PV sites in structurally normal hearts.

4.2. Autonomic mechanism for rapid firing-mediated AF

The mechanism operative in rapid PV firing that initiates AF is not well understood. Both triggered activity and reentry have been shown to generate rapid firing.3,4,17,18 However, reentry occurring clinically must be initiated by spontaneous premature beats. Notably, for the vast majority of the AF induced by rapid firing, the initial premature beat and following rapid discharges all appear to arise from the same site, implying that a common mechanism may be responsible for providing the premature beat and the following rapid discharges; the latter can be either triggered activity or reentry. This common mechanism is indeed the main focus of this study.

By delivery of HFS during atrial refractoriness to a superfused canine PV-atrial preparation, Patterson et al.3 demonstrated that rapid triggered firing could be induced. This response was inhibited by tetrodotoxin, atropine, or atenolol, indicating that both parasympathetic and sympathetic neural elements are involved in such triggered firing. The authors hypothesized that activation of the ICANS leads to local release of both cholinergic and adrenergic neurotransmitters.3 The former causes shortening of refractoriness, whereas the latter induces a rise in intracellular Ca2+, leading to early after-depolarizations and rapid focal discharges. Another study by Patterson et al.4 induced similar rapid firings by administering acetylcholine and norepinephrine. The first beat, showing a centrifugal conduction pattern by optical mapping, was found to be caused by triggered activity. The rest of the rapid firing was caused by either triggering or reentry. Multi-electrode mapping with 56 electrodes in the PV in patients with AF defined a focus as a site with maximal dimension ≤ 1 cm that initiates centrifugal, concentric activation,19 corroborating the findings from the in vitro studies. In the present study, we hypothesized that the focal firing was initiated by an autonomic mechanism that involves the activation of the ICANS and our results support this hypothesis. While the muscarinic receptor, KACh channel and β-receptor are all known to be critical elements in modulating the cellular responses to autonomic stimulation, the contribution from other membrane or subcellular proteins or hormones remains to be understood.

4.3. Interactive GP in the ICANS

Previous studies have demonstrated that the atrial GP form an interconnected autonomic network to regulate the sinoatrial nodal and atrioventricular nodal function.20,21 In this study, ablation of either the left-sided GP (SLGP, ILGP and LOM) or right-sided GP (ARGP and IRGP) on the atria significantly increased the AF threshold induced by HFS at a distant site (Tables 1–3; Figure 4). These observations underscore the critical role of the interconnected autonomic network formed by the ICANS. Other studies22 also showed that stimulating the GP in patients induced fractionated electrograms in contralateral PVs 4–5 cm away. Injection of acetylcholine into ARGP induced rapid firings at contralateral LSPV.23 These observations along with the present study suggest that these GP on the atria, acting as ‘integration centers’ in the ICANS, are extensively interactive in modulating pathophysiological functions of the PVs and atria. Stimulation or inhibition of GP on one side can enhance or suppress AF inducibility at a distant site through the ICANS.

4.4. Extrinsic and intrinsic autonomic nervous system

It is known that stimulation of the vagosympathetic trunks markedly suppresses the sinus and AV nodal function and enhance the initiation and maintenance of AF. In the present study, VTS significantly increased the AF inducibility by HFS delivered at multiple atrial and PV sites. We hypothesized that the extrinsic autonomic nervous system may contribute to the initiation of focal firing via activation of intrinsic ANS. This is supported by the observation that VTS did not reduce the AF threshold after GP ablation (Figure 5).

4.5. Ligament of Marshall

Histological and functional studies12–15 showed that both sympathetic and parasympathetic elements are present along the LOM. The present study showed the AF threshold at left PVs and atrium was increased by ablation of the SLGP and ILGP (Table 2), and was further increased by ablation of the neural elements in the LOM (Table 3). These results are consistent with the observations by Doshi et al.14 and Lin et al.15 that autonomic neural elements in the LOM play an important role in the formation of rapid firing in dogs.

4.6. Clinical implications

Clinical studies1,2 showed that a subgroup of AF patients with rapid firings coming from PV and non-PV sites. The mechanism(s) operative in such rapid firing in patients with paroxysmal AF but without structural heart diseases remains poorly understood. Previous reports3–8 showed that some of the rapid PV firings are autonomically mediated and can be attenuated or eliminated by interruption of the ICANS. In the present study, AF was also easily inducible by HFS in normal dogs and AF became non-inducible or very difficult to induce after autonomic denervation, suggesting that the ICANS may have an essential causative role in conjunction with other mechanisms responsible for rapid firing. Since standard PV isolation for the treatment of paroxysmal AF involves inadvertent partial ablation of the ARGP, SLGP, LOM and many autonomic nerves, autonomic denervation may contribute to the success of PV isolation in the treatment of paroxysmal AF. The data presented in this study support this hypothesis.

4.7. Methodology considerations

In the present study, HFS was applied during the myocardial refractory period to activate autonomic nervous terminals. It is arguable that by releasing neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, 40 ms of HFS may produce enough shortening of the refractoriness to permit capturing and direct electrical stimulation of the myocardium to initiate AF. However, several observations did not support direct stimulation of myocardium: (i) There is always a latency (30–200 ms) between the end of HFS and the beginning of rapid firing. If direct myocardial stimulation was the cause of rapid firing, such firing should have started during the 40 ms HFS or immediately after the end of HFS. (ii) If one of the stimuli during the HFS did capture the myocardium, it would initiate only a single captured beat, not runs of rapid firing since all the rest of the stimuli during the 40 ms train would fall into the refractory period of the captured beat. (3) Both atropine and esmolol markedly increased the voltage that was required to induce rapid firing, which should not have changed if all the rapid firing was induced by direct myocardial stimulation.

In this study, multiple GP in the epicardial fat pads were ablated. It is possible that unintended destructions of the myocardium at the atria or PV sleeves after ablation may contribute to the increase of AF threshold. However, the histological examination in a recent study8 showed that the damage to the underlying myocardium by GP ablation was minimal. Furthermore, the observation that the threshold for AF inducibility on atrium or PVs was increased after ablation of the contralateral GP 4–5 cm away, further confirms that the potential damage to the myocardium by ablation is not an important factor. In animals without GP ablation (Group 3), administration of autonomic blockers suppressed or eliminated rapid AF at all sites, indicating that neural elements are the predominant factor for the genesis of rapid firing.

5. Conclusion

HFS applied to local atrial and PV sites initiated rapid firing via activation of the interactive autonomic network formed by the ICANS in the heart. Autonomic denervation suppresses or eliminates those rapid firings. Since standard PV isolation for the treatment of paroxysmal AF involves inadvertent partial denervation, autonomic denervation may contribute to the success of PV isolation in the treatment of paroxysmal AF.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grant 0650077Z from the American Heart Association (to S.S.P.), grant K23HL069972 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (to S.S.P.), grant from the Helen and Wil Webster Arrhythmia Research Fund of the University of Oklahoma Foundation (to B.J.S.), grant 30700313 from National Natural Science Foundation of China (to Z.L. and H.J.), and grant 200750730309 from Disciplinary Leadership in Scientific Research Project of Wuhan City, China (to Z.L. and H.J.).

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Joseph Klimkoski and Tushar Sharma for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang C, Wu TJ, Doshi RN, Peter CT, Chen PS. Vein of Marshall cannulation for the analysis of electrical activity in patients with focal atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;101:1503–1505. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson E, Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Lazzara R. Triggered firing in pulmonary veins initiated by in vitro autonomic nerve stimulation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson E, Lazzara R, Szabo B, Liu H, Tang D, Li YH, et al. Sodium-calcium exchange initiated by the Ca2+ transient: an arrhythmia trigger within pulmonary veins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1196–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Yamanashi WS, Edwards J, Zhou J, Wu R, et al. Experimental model for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation arising at the pulmonary vein–atrial junctions. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherlag BJ, Hou YL, Lin J, Lu Z, Zacharias S, Dasari T, et al. An acute model for atrial fibrillation arising from a peripheral atrial site: evidence for primary and secondary triggers. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:519–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Z, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Niu G, Ghias M, Jackman WM, et al. Autonomic mechanism for complex fractionated atrial electrograms: evidence by fast Fourier transform analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:835–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Z, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Niu G, Fung K-M, Zhao L, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation: autonomic mechanism for atrial electrical remodeling induced by short-term rapid atrial pacing. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2008;1:184–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.784272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherlag BJ, Nakagawa H, Jackman WM, Yamanashi WS, Patterson E, Po S, et al. Electrical stimulation to identify neural elements on the heart: their role in atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2005;13:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s10840-005-2492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan BX, Ardell JL, Hopkins DA, Losier AM, Armour JA. Gross and microscopic anatomy of the canine intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Anat Rec. 1994;239:75–87. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092390109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauza DH, Skripka V, Pauziene N. Morphology of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system in the dog: a whole-mount study employing histochemical staining with acetylcholinesterase. Cells Tissues Organs. 2002;172:297–320. doi: 10.1159/000067198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makino M, Inoue S, Matsuyama TA, Ogawa G, Sakai T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Diverse myocardial extension and autonomic innervation on ligament of Marshall in humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:594–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulphani JS, Arora R, Cain JH, Villuendas R, Shen S, Gordon D, et al. The ligament of Marshall as a parasympathetic conduit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1629–H1635. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00139.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doshi RN, Wu TJ, Yashima M, Kim YH, Ong JJ, Cao JM, et al. Relation between ligament of Marshall and adrenergic atrial tachyarrhythmia. Circulation. 1999;100:876–883. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin J, Scherlag BJ, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Liu S, Patterson E, et al. Inducibility of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias along the ligament of Marshall: role of autonomic factors. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:955–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schauerte P, Scherlag BJ, Patterson E, Scherlag MA, Matsudaria K, Nakagawa H, et al. Focal atrial fibrillation: experimental evidence for a pathophysiologic role of the autonomic nervous system. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:592–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arora R, Verheule S, Scott L, Navarrete A, Katari V, Wilson E, et al. Arrhythmogenic substrate of the pulmonary veins assessed by high-resolution optical mapping. Circulation. 2003;107:1816–1821. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000058461.86339.7E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Po SS, Li Y, Tang D, Liu H, Geng N, Jackman WM, et al. Rapid and stable re-entry within the pulmonary vein as a mechanism initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1871–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson E, Jackman WM, Beckman KJ, Lazzara R, Lockwood D, Scherlag BJ, et al. Spontaneous pulmonary vein firing in man: relationship to tachycardia-pause early afterdepolarizations and triggered arrhythmia in canine pulmonary veins in vitro. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1067–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhou J, Song J, Zhang Y, et al. Interactive atrial neural network: determining the connections between ganglionated plexi. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Truong K, et al. Ganglionated plexi modulate extrinsic cardiac autonomic nerve input: effects on sinus rate, atrioventricular conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Nakagawa H, Po SS, Scherlag BJ, Wu R, Beckman KJ, et al. Autonomic ganglionated plexi stimulation induces fractionated atrial potentials in contralateral pulmonary veins in patients with atrial fibrillation (abstract) Circulation. 2006;114:454. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin J, Scherlag BJ, Zhou J, Lu Z, Patterson E, Jackman WM, et al. Autonomic mechanism to explain complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE) J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1197–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]