Abstract

Purpose

The current study examined the long-term relationship of early adolescent alcohol use to number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood.

Methods

Using data from a 10-year longitudinal study, we collected data on 6th and 7th grade students’ alcohol use and their lifetime number of sexual partners ten years later.

Results

We found a significant effect of early alcohol use in the 6th and 7th grades on lifetime number of sexual partners 10 years later, controlling for gender, age, race, peer norms, and sensation seeking. Early age at first intercourse mediated the association between early alcohol use and number of sexual partners.

Conclusions

Interventions focused on preventing use of alcohol at an early age may have the potential to reduce risks for sexually transmitted diseases during adolescence and emerging adulthood.

The majority of girls and boys engage in sexual intercourse at some point during adolescence, many with multiple sexual partners,1 putting them at greater risk of having unplanned pregnancies and contracting sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) including HIV.2,3 Adolescent sexual activity is an important health concern, as almost half of all STDs each year are among people between the ages of 15 and 24.4 Given these threats to the sexual health of adolescents, it is critical to identify early predictors of sexual risk-taking in adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Problem behavior theory suggests that risky behaviors adopted during childhood or early adolescence put youth on a developmental trajectory that leads to other risky behaviors later in life.5,6 Risky sexual behavior is viewed as a violation of a social norm affected by an individual’s attitudes, and this behavior often covaries with other norm-breaking behaviors such as substance use and delinquency.7 Alcohol use in early adolescence is a particularly relevant risk behavior, as youth are more likely to drink than use other drugs,8 and national surveys show that drinking behavior usually increases between the 7th and 10th grades.9

Alcohol impairs judgment10 and may increase the risk for unplanned, casual sex by diminishing an individual’s ability to consider adverse consequences.11 Studies have shown that early use of alcohol is associated with an earlier age of first intercourse12,13 and engaging in sexual activity with multiple sex partners.14 However, methodological features of these studies limit the ability to draw temporal, if not causal, inferences about the association between alcohol use and risky sex. First, many of these studies were cross-sectional in nature, sampling youth at only one point in adolescence.15,16 Second, some of the existing longitudinal studies either did not assess alcohol use early in adolescence when drinking behavior typically begins17,18 or did not follow students beyond the high school years.19 Third, several of these studies concentrated on alcohol use during the past month,17 but given that only 7% of 8th grade adolescents report being drunk in the past month,9 total lifetime use of alcohol may be a more representative measure of the drinking behavior of young adolescents. Similarly, previous studies have typically assessed number of sexual partners during the past year.20,21,22 Because half of adolescents report having sex at least once by the 12th grade,23 lifetime sexual experience may be a more valid indicator of sexual experience from adolescence to the early adult years. Fourth, although research has established an association between alcohol use and early intercourse initiation, few studies have had the benefit of an extended longitudinal design and tested early age at first intercourse as a mechanism by which early adolescent drinking influences later sexual behavior. Finally, several studies have suggested that other variables may mitigate the relationship between early drinking and later sexual behavior, including sensation seeking,24 and peer norms about alcohol use,25 suggesting that longitudinal studies should consider these important factors.

Current Study

The current study evaluated the long-term relationship between early adolescent alcohol use and sexual behavior in emerging adulthood 10 years later using cumulative measures of alcohol use (i.e., total lifetime drinking behavior) and sexual behavior (i.e., total number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood) and tested early age at first intercourse as a critical mediator. Because these data do not involve experimental manipulation, significant findings can only support particular causal pathways, but cannot rule out the possibility that an unknown “third variable” accounts for significant associations among the variables. Accordingly, we included several important covariates in order to eliminate alternative explanations for our results, including gender, age, race, peer norms about drinking, and sensation seeking.

Method

Participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California. Two longitudinal samples were derived from an ongoing drug abuse prevention trial, the Midwestern Prevention Project, which has been implemented since 1984 in Kansas City and since 1987 in Indianapolis, Indiana. The program was introduced into schools during the initial grant period of the study between grades 6/7 and 12 (from 1984 through 1992). Details of the program intervention are described elsewhere.26 All students in these schools gave full active parental and self-consent prior to participation (response rate > 96%). The Kansas City sample (N = 1002) was based on entering 6th and 7th grade students from eight schools and the Indianapolis sample (N = 1206) was based on entering 6th and 7th grade students from 57 schools. Both samples were demographically matched, randomly assigned to a program or control condition, and targeted for follow-up through emerging adulthood. The current study used data from Time 1 (i.e., approximately age 12) and a follow-up assessment ten years later (i.e., approximately age 22). Details of follow-up sample selection, attrition, population and experimental group representativeness are reported elsewhere,27 which showed slightly greater loss of males, but no differential loss of alcohol users or program group over time.

Time 1 Measures: Early Adolescence

Demographic variables

Gender (0 = female; 1 = male), race/ethnicity (0 = non-White; 1 = White), grade at Time 1 (0 = 6th grade; 1 = 7th grade), and experimental intervention group (0 = control; 1 = program) were included as covariates.

Early alcohol use

To assess lifetime alcohol use, participants were asked: “How many alcoholic drinks (beer, wine, or liquor) have you ever had in your whole life?” (none, only sips, part or all of one drink, 2 to 4 drinks, 5 to 10 drinks, 11 to 20 drinks, 21 to 100 drinks, more than 100 drinks). The mean was approximately 1 drink, consistent with previous research on early adolescent drinking.9 Ten percent of the sample reported never having a sip of alcohol, 37% only sips, 31% part or all of one drink, and 22% 2 or more alcoholic drinks in their lifetime. Thus, 90% reported some lifetime alcohol use, a rate also consistent with previous research.9 Because we were primarily interested in distinguishing adolescents who would be willing to engage in unsanctioned alcohol consumption, we compared participants who reported having no alcohol or only sips (47% of sample; coded as 0) to those who reported having at least part of a drink or one or more drinks (53% of sample; coded as 1).

Peer norms about alcohol use

The alcohol use of participants’ peers was assessed with one item: “How many of your close friends drink alcohol (beer, wine, or liquor)” (none; 1, 2, 3 or 4; 5 to 7; 8 to 10; more than 10). The mean response was 0.72 (SD = 1.21), representing approximately 1 close friend engaging in alcohol use. To simplify the data analysis, we compared participants with no friends using alcohol with participants with ≥ 1 friend using alcohol.

Sensation seeking

Two items adapted from the Sensation Seeking Scale28 were “Do you like to take chances?” and “Is it worth getting into trouble if you have fun?” Both items were measured on a 4-point scale (1 = never to 4 = most of the time) and were aggregated to create a composite variable (correlation between the 2 items =.40, p <.001) with a range from 1 to 8. The mean composite sensation seeking score was 4.41 (SD = 1.55).

Time 2 Measures: Emerging Adulthood (10 Year Follow-Up)

Lifetime number of sexual partners

Participants were asked if they have ever engaged in sexual intercourse. The participants who responded “yes” (94% of the total sample) were asked: “In your lifetime, approximately how many sexual partners have you had?” (1, 2–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, 21–40, more than 40). This question was derived from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). The mean response was 2.65 (SD = 1.48), representing approximately 4 sexual partners. Participants who responded “no” to the initial question were coded as “0” or no sexual partners. As a comparison, the median number of lifetime sexual partners for men age 25–44 is 6.7 and 3.8 for women.29

Age of first sexual intercourse

Similar to other assessments of coital debut; 30,31 sexually active participants indicated the age at which they first engaged in sexual intercourse. The mean age of first sex was 16.32 (SD = 2.27).

Treatment of Missing Data and Final Sample

Of the original 2208 participants at Time 1539 (70%) completed the assessment at Time 2; due to a planned missingness procedure whereby only two-thirds of the forms included the sensation seeking scale,32 476 were missing this variable. This retention rate is similar to other studies.33 In order to be included in the analyses, participants had to complete all measures on the surveys at both time points. As a control for Time 1 sexual activity, we removed the 139 participants who reported an age at first sex ≤ 13. The final sample was 924 participants (78% White, 20% African-Americans, and 2% from other races/ethnicities; 56% female; and 74% in the 7th (vs. 6th) grade at Time 1). Participants who completed the Time 2 assessment were more likely to be White, female, and from the control condition, have fewer peers using alcohol, and less likely to use alcohol at Time 1.

Data Analysis Strategy

Previous analyses have shown no differences between program and control groups in substance use at Time 1.26 We used SAS PROC MIXED34 with individual as unit and controlling for cluster effect of original school (N = 8 in Kansas, N = 57 in Indianapolis) in order to calculate the ICC (intra-class correlation coefficient) for lifetime alcohol use at Time 1 and for number of sexual partners at Time 2. The ICCs for Kansas and Indianapolis were very small indicating that the cluster effect of school was negligible; therefore, we simplified the analytic strategy by ignoring the nested design. Statistical analyses also indicated that program intervention assignment yielded no prediction nor did it affect any of the other statistical tests; nevertheless, we retained program intervention as a covariate in all analyses.

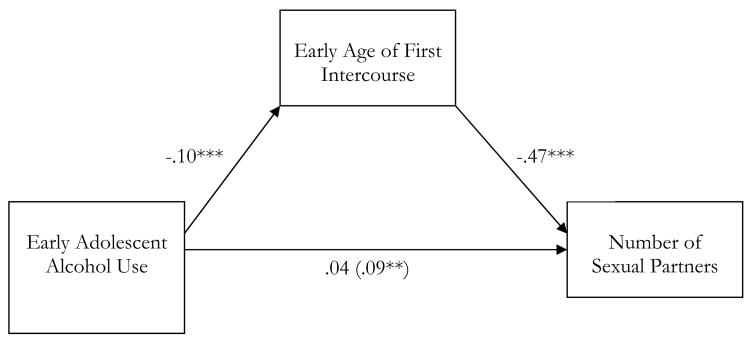

We examined the association between early alcohol use at Time 1 and lifetime number of sexual partners at Time 2 using path analysis controlling for grade, gender, race/ethnicity, peer norms about alcohol use, sensation seeking, and program intervention. Because lifetime sexual partners were collected on an ordinal response scale, we treated it as an ordered categorical dependent variable and used a standard logistic link function. The assumption that the covariate and predictor relationships were consistent for all logits (i.e., parallel lines assumption) was confirmed using SPSS 16 prior to fitting the path models. Mediation was tested via path analysis using newer recommendations36 to use bootstrapping to create empirical standard errors for the mediating effect (see Figure 1). To ascertain the strength of the mediating effect, Model 1 tested the covariates without the mediator (age at first intercourse), followed by Model 2, which tested the mediation effect. All analyses were conducted using Mplus 5.2.37

Figure 1.

Standardized Results Depicting Early Age at First Intercourse as a Mediator between Early Drinking and Number of Sexual Partners by Emerging Adulthood.

Note. N = 964; ***p <.001, **p <.01, *p <.05. Original direct effect in parentheses.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics regarding reported lifetime sexual partners. Most of the sample (43%) reported 2–5 partners in their lifetime. Gender, race, group, and grade were all independent of lifetime sexual partners as assessed by chi-square tests of independence. However, participants with friends who consumed alcohol tended to be more likely to have 16 or more partners, and participants who drank at an early age tended to have more partners.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Number of Lifetime Sexual Partners and Bivariate Relationships among Predictors and Covariates.

| Lifetime Sexual Partners | Chi-squarea | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2–5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | 16–20 | 21–40 | 41+ | ||

| Sample | 5 | 148 | 413 | 216 | 87 | 44 | 38 | 13 | |

| Frequencies | |||||||||

| Percent Male | 40.0% | 44.6% | 37.8% | 43.1% | 48.3% | 38.6% | 50.0% | 61.5% | Χ2(6)=8.2 |

| Percent White | 80.0% | 89.2% | 85.7% | 89.4% | 86.2% | 81.8% | 78.9% | 61.5% | Χ2(6)=12.1 |

| Percent Early Drinkers | 20.0% | 41.2% | 48.4% | 53.7% | 52.9% | 59.1% | 65.8% | 69.2% | Χ2(6)=13.6* |

| Percent 7th Graders | 60.0% | 73.0% | 67.6% | 78.7% | 75.9% | 70.5% | 78.9% | 76.9% | Χ2(6)=10.7 |

| Percent with friends who drank | 60.0% | 69.6% | 59.1% | 56.5% | 59.8% | 43.2% | 28.9% | 53.8% | Χ2(6)=25.9* |

| Percent in control group | 40.0% | 45.3% | 48.9% | 54.6% | 51.7% | 50.0% | 42.1% | 53.8% | Χ2(6)=4.5 |

| Coital debut Mean (SD) | 17.0 (2.3) | 18.4 (1.3) | 17.1 (1.7) | 16.2 (1.6) | 15.9 (1.6) | 15.2 (1.6) | 15.4 (1.1) | 15.3 (1.5) | |

| Sensation seeking Mean (SD) | 4.3 (0.0) | 4.1 (1.3) | 4.3 (1.2) | 4.4 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.2) | 4.4 (1.3) | 4.4 (1.5) | |

Notes. denotes significant chi-square at 0.05 alpha level. Chi-square test of independence did not include the five people who reported no age of first intercourse because of small expected values.

Table 2 presents the standardized results of the two models tested. Model 1 showed that early alcohol use predicted having more sexual partners by emerging adulthood, even after controlling for sex, grade, race/ethnicity, peer norms, sensation seeking, and current alcohol use. Non-Whites (marginally significant) and those with at least one risky peer in early adolescence also reported having a greater number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood. There were no significant interactions between early adolescent alcohol use and either sex or race/ethnicity in predicting number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood.

Table 2.

Standardized Results from the Bootstrapped Mediational Path Models Predicting Lifetime Number of Sex Partners from Early Adolescent Alcohol Use, Covariates, and Age of First Intercourse.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking in early adolescence | .09** | .04 |

| Sex of participant | .03 | .04 |

| Grade of participant | .02 | .02 |

| Race/ethnicity | −.07† | −.07† |

| Treatment/control group | −.02 | −.02 |

| Peer norms about alcohol use | −.10** | −.10** |

| Sensation seeking | .05 | .06 |

| Age of first intercourse | −.47*** | |

| Drinking in early adolescence predicting age of first intercourse | −.10*** |

Note. N = 964,

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.06

We then examined age at first sexual intercourse as a mediator of the association between early alcohol use and number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood (see Figure 1). The path model depicted in Figure 1 was bootstrapped 1,000 times with samples sizes equal to n. The bootstrapped standard errors were used to assess the significance of the mediating effect. As shown in Table 2 (Model 2), early adolescent drinking was associated with age at first intercourse, which was in turn associated with lifetime number of sexual partners. Moreover, without accounting for age at first intercourse, early adolescent drinking predicted lifetime sexual partners, but after including the mediating effect, this relationship became nonsignificant, providing evidence for full mediation. This was confirmed by the indirect effect test using the bootstrapped standard error, β =.05, p <.001.

Discussion

Although numerous studies have investigated the link between early adolescent drinking behavior and later sexual behavior, many of these studies were either cross-sectional or short-term longitudinal studies that limit our ability to draw temporal inferences about the association between alcohol use and risky sex. In this 10-year longitudinal study, we found that early adolescent alcohol use was associated with an earlier age of first intercourse and, in turn, with having a greater number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood. This association remained significant after controlling for other important contributors, including age/grade, ethnicity, sensation seeking, peer norms about alcohol use, and current alcohol use. These results go beyond current research by showing that drinking in early adolescence may put adolescents on a risky sexual lifestyle trajectory, leading to frequent sexual encounters with new partners, thus providing important implications for STD transmission as the likelihood of contracting an infection compounds with each additional sexual partner.38

There were several important effects of the covariates on the number of acquired sexual partners by emerging adulthood. Non-White participants reported marginally more sexual partners than did White participants, confirming previous findings.39 Participants with at least one risky peer in early adolescence also reported significantly more sexual partners ten years later. Sensation seeking was not associated with lifetime number of sex partners.

Several limitations should be noted. First, the IRB approval did not allow for questions about sexual behavior prior to age 18, thus we do not know at what specific age most of these sexual encounters occurred. Some participants may have had all their sexual interactions before entering college, while others may not have accumulated their sexual experiences until shortly before the Time 2 assessment. Second, our study did not explore whether these sexual encounters were casual and unplanned, and future research is needed to address this question. Third, given that this study relied on existing data, all of the variables were measured with only one or two key indicators. Fourth, we should acknowledge that age at first intercourse and number of sexual partners were assessed concurrently, which may have produced biased self-reports. Finally, although participants in this study had been in a previous drug use prevention study, results were identical regardless of whether study condition was included in the analyses. Nevertheless, future research is needed to replicate the findings in a new sample and to examine the impact of early drinking on condom use behavior in emerging adulthood.

These findings have two important implications for designing future prevention programs. First, current evidence-based drug abuse prevention programs that address alcohol use in early adolescence may have the potential to significantly lower risk for contracting STDs later in adulthood potentially by delaying adolescents’ first experience of intercourse and number of sexual partners by emerging adulthood. Second, the results suggest that we can potentially intervene to reduce young adults’ risk for contracting STDs far earlier than the onset of sexual activity in adolescence or emerging adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a NIDA grant (DA010366) to Pentz (P.I.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Amy Strachman, Institute for Prevention Research, University of Southern California

Emily A. Impett, Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California, Berkeley

James Matthew Henson, Department of Psychology, Old Dominion University

Mary Ann Pentz, Institute for Prevention Research, University of Southern California

References

- 1.CDC. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing. Vital and Health Statistics. 2002;23:1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finer LB, Darroch JE, Singh S. Sexual partnership patterns as a behavioral risk factor for sexually transmitted diseases. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:228–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55(SS5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstock H, Berman CW. Sexually Transmitted Diseases among American Youth: Incidence and Prevalence Estimates. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2000;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper ML, Wood PK, Orcutt HK, et al. Personality and the Predisposition to Engage in Risky or Problem Behaviors during Adolescence. J of Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:390–410. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jessor R, Van Den Bos J, Vanderryn J, et al. Protective Factors in Adolescent Problem Behavior: Moderator Effects and Developmental Change. Dev Psych. 1995;31:923–933. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellickson PL, Hays RD, Bell RM. Stepping through the Drug Use Sequence: Longitudinal Scalogram Analysis of Initiation and Regular Use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:441–451. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, et al. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2006, Volume I: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. NIH Publications N0-07-6205. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steel CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol Myopia—Its prized and Dangerous Effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter MR, et al. Early Age of First Drunkenness as a Factor in College Students’ Unplanned and Unprotected Sex Attributable to Drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:34–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo J, Stanton B, Cottrell L, et al. Substance Use among Rural Adolescent Virgins as a Predictor of Sexual Initiation. J Adol Health. 2005;37:252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen W, Samuelsen SO, Wichstrom L. Intercourse Debut Age: Poor Resources, Problem Behavior, or Romantic Appeal? A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. J Sex Research. 2003;40:333–345. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper ML. Does Drinking Promote Risky Sexual Behavior? A Complex Answer to a Simple Question. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter DL, Valois RF, McKewon RE, et al. Correlates of Condom Use and Number of Sexual Partners among High School Adolescents. J Sch Health. 1993;63:91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, et al. Multiple Sexual Partners among U.S. Adolescents and Young Adults. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TK, et al. Risky Sex Behavior and Substance Use among Young Adults. Health Soc Work. 1999;24:147–154. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells JE, Horwood LI, Fergusson DM. Drinking Patterns in Mid-Adolescence and Psychosocial Outcomes in Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood. Addiction. 2004;99:1529–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stueve A, O’Donnell LN. Early Alcohol Initiation and Subsequent Sexual and Alcohol Risk Behaviors among Urban Youths. Am J Public Health. 2005;5:887–893. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogart LM, Collins RL, Ellickson PL, et al. Adolescent Predictors of Generalized Health Risk in Young Adulthood: A 10-year Longitudinal Assessment. J Drug Issues. 2006;36:571–596. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo J, Chung I, Hill KG, et al. Developmental Relationships between Adolescent Substance Use and Risky Sexual Behavior in Young Adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:354–362. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkes A, Wight D, Henderson M, et al. Explaining Associations between Adolescent Substance Use and Condom Use. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:180e1–180.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.YRBS. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991–2005. Trends in the Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors. 2005 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/2005_YRBS_Sexual_Behaviors.pdf.

- 24.Zuckerman M, Kuhlman DM. Personality and Risk-Taking: Common Biosocial Factors. J Pers. 2000;68:999–1029. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Yoerger K. Middle Childhood Antecedents to Progressions in Male Adolescent Substance Use: An Ecological Analysis of Risk and Protection. J Adol Research. 1999;14:175–205. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pentz MA, MacKinnon DP, Flay BR, et al. Primary Prevention of Chronic Diseases in Adolescence: Effects of the Midwestern Prevention Project on Tobacco Use. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:713–724. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riggs NR, Chou C, Pentz MA. Protecting against intergenerational problem behavior: Mediational effects of prevented marijuana use on second-generation parent-child relationships and child impulsivity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuckerman M, Kolin EA, Price L, et al. Development of a Sensation-Seeking Scale. J Consult Psychol. 1964;28:477–482. doi: 10.1037/h0040995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. [Accessed November 5, 2008];National Survey of Family Growth. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

- 30.Martino SC, Elliott MN, Collins RL, et al. Virginity Pledges among the Willing: Delays in First Intercourse and Consistency of Condom Use. J Adol Health. 2008;43:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller TE, Gavin LE, Kulkarni A. The Association between Sex Education and Youth’s Engagement in Sexual Intercourse, Age at First Intercourse, and Birth Control Use at First Sex. J Adol Health. 2008;42:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, et al. Planned Missing Data Designs in Psychological Research. Psychol Methods. 2006;11:323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun W, Skara S, Sun P, et al. Project Towards No Drug Abuse: Long-Term Substance Use Outcomes Evaluation. Prev Med. 2006;42:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latour D, Latour K, Wolfinger RD. Getting Started with PROC MIXED. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT Software: Changes and enhancements through release 6.11. Cary, NC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthen B, Muthen L. Computer Software. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2008. MPlus. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niccolai LM, Ethier KA, Kershaw TS, et al. New Sex Partner Acquisition and Sexual Transmitted Disease Risk among Adolescent Females. J Adol Health. 2004;34:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CDC. [Accessed September 8, 2008];Percentage of students who had sexual intercourse with four or more persons during their life. 2007 Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss/QuestYearTable.asp?cat=4&Quest=Q60&Loc=XX&Year=2007&compval=&Graphval=yes&path=byHT&loc2=&colval=2007&rowval1=Race&rowval2=Sex&ByVar=CI&Submit2=GO.