Abstract

Mutations in a variety of myofibrillar genes cause dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in humans, usually with dominant inheritance and incomplete penetrance. Here, we sought to clarify the functional effects of the previously identified DCM-causing TTN 2-bp insertion mutation (c.43628insAT) and generated a titin knock-in mouse model mimicking the c.43628insAT allele.

Mutant embryos homozygous for the Ttn knock-in mutation developed defects in sarcomere formation and consequently died before E9.5. Heterozygous mice were viable and demonstrated normal cardiac morphology, function and muscle mechanics. mRNA and protein expression studies on heterozygous hearts demonstrated elevated wild-type titin mRNA under resting conditions, suggesting that up-regulation of the wild-type titin allele compensates for the unstable mutated titin under these conditions.

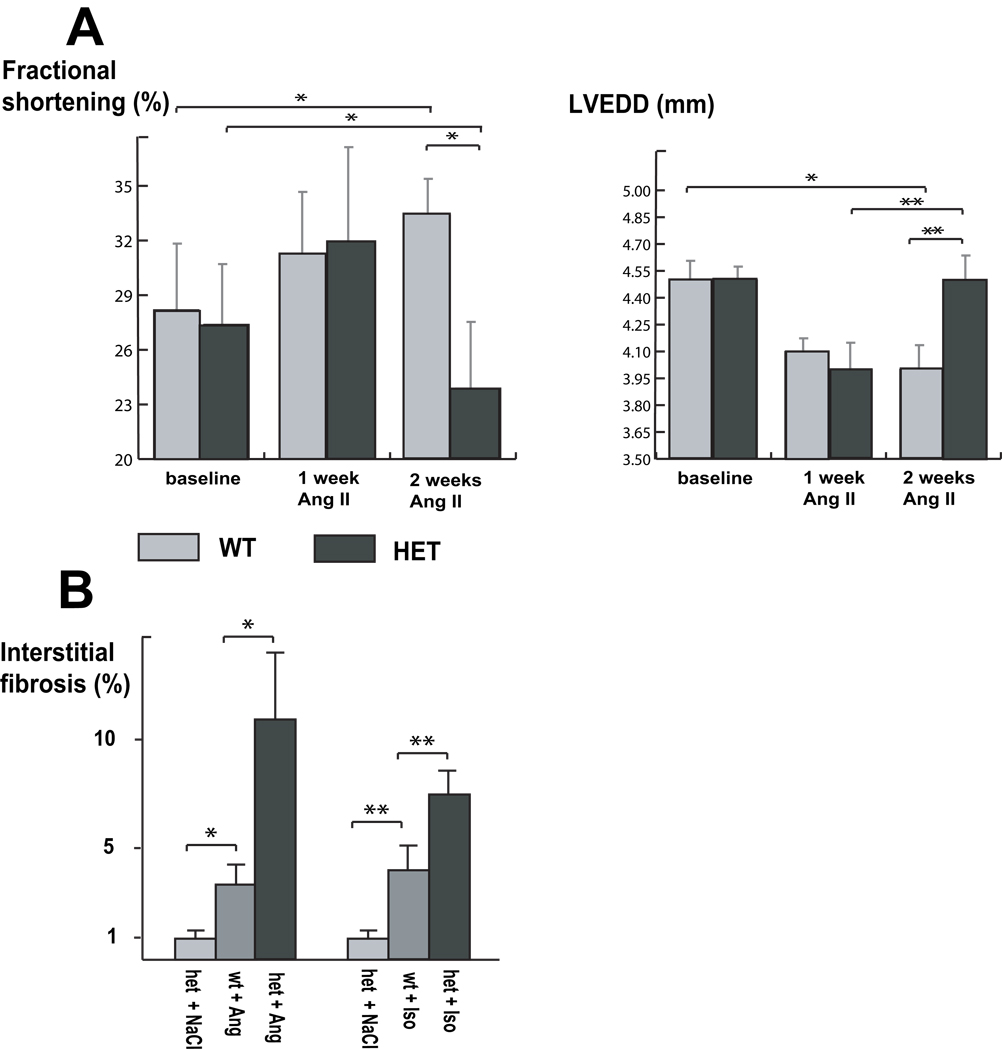

When chronically exposed to angiotensin II or isoproterenol, heterozygous mice developed marked left ventricular dilatation (p<0.05) with impaired fractional shortening (p<0.001) and diffuse myocardial fibrosis (11.95 ± 2.8% versus 3.7 ±1.1%). Thus, this model mimics typical features of human dilated cardiomyopathy and may further our understanding of how titin mutations perturb cardiac function and remodel the heart.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Development, Sarcomere formation, Genetics, Mouse model, Heart failure, Pathogenesis, Titin

1. Introduction

Heart failure is a major and growing cause of human morbidity and mortality in the world, responsible for more than 10,000 deaths annually in the United States only [1]. Heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a familial disease in 20–35% of cases and is clinically characterized by ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction. The molecular mechanisms by which the mutated proteins result in heart failure are complex and incompletely understood: Familial DCM is associated with mutations in genes encoding a broad range of proteins, e.g. sarcomeric, cytoskeletal, and nuclear membrane proteins, as well as proteins involved in Ca(2+) metabolism, suggesting that various pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of heart failure [2].

Here we have attempted to characterize the morphological and functional impairments that result from a mutation in the giant filamentous protein titin: titin is responsible for autosomal dominant DCM in humans (OMIM188844, see [3,4,5]) and is functionally linked to the control of myocellular mechanics [6].

Titin is the largest single protein known; the entire coding region consists of 363 exons, which encode polypeptides of up to 3.7 MDa in size. Like a myofibrillar backbone, titin filaments up to 1µm in length span half sarcomeres from the Z-disk to the M-line [7]. Titin acts as a molecular scaffold for sarcomere assembly; plays a putative role in the myocardial stress-response machinery, and, through its elastic domains, contributes substantially to the diastolic properties of the heart [6,8]. Furthermore it has been reported that changes in titin expression, with a shift to the more compliant N2BA isoform, occurs in patients with DCM, thereby significantly impacting diastolic filling by lowering myocardial stiffness [9].

During recent years, various animal and tissue culture models have been generated to dissect the structural, mechanical, and signalling functions of titin [6,8,10–16]. However, so far it is not well understood how mutant titin alleles in human patients cause either HCM [5], or DCM [3,4], and if the mutant and wild-type alleles are co-expressed or not. Here, we generated a mouse model that recapitulates a TTN truncation mutation (c.43628insAT), a mutation that was previously identified in a large family with autosomal dominant DCM [3]. By homologous recombination, we introduced this 2-bp AT-insertion into the corresponding site of the mouse titin gene. This animal model allows dissection of affected pathways leading to titin-based DCM. Homozygous mice died in utero before E9.5 as a result of defects in sarcomere formation. Heterozygous animals showed no alterations in cardiac morphology and function. However, when exposed to cardiac stressors (angiotensin II, isoproterenol), heterozygous animals developed typical morphological and functional features of DCM significantly earlier and more pronounced compared to wild-type mice, thereby recapitulating the human phenotype.

2. Materials and Methods

An expanded version of the Methods is available in the online Data Supplement.

2.1 Generation of Ttn Knock-in mouse model

Gene targeting was performed using a targeting vector that includes the human TTN mutation c.43628insAT at the corresponding site in the mouse genome, followed by a neomycin resistance cassette with a poly-adenylation signal. Experimental procedures regarding the generation, genotyping, morphological, histological, and ultrastructural characterization of the knock-in mice are described in the online data supplement. Homozygous embryos were obtained by time-mated crossings of heterozygous mice. Embryos and resorption bodies were harvested from E8.5–E13.5. Histology, electron microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy of mouse embryos were performed as described in the expanded methods online.

All animal investigations were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, as well as by the Berlin Animal Review Board (Reg. G0115/05).

2.2 Expression analysis

We determined the expression levels of cardiac mRNA (n=8 per genotype) for selected molecular markers of heart failure and titin ligands involved in myofibrillar signal transduction and Ca(2+) signalling (detailed information in the expanded methods online). Frozen tissue samples from LV apexes (n=8 per genotype) were homogenized in 6M urea buffer using a pestle and mortar and separated on 2% (w/v) agarose gels essentially as described [17]. The relative amounts of titin, nebulin, and myosin were compaired by densitometry of coomassie-stained agarose gels. For the detection of potential minor truncated titin species, more sensitive silver stains were used. The separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, incubated with an antibody directed against Z1Z2 and M8M9 and detected by an AP-conjugated secondary antibody.

2.3 Muscle mechanics and cardiac function

Papillary muscles were isolated from mouse LV and mechanically investigated as described previously [18,19]. Additional information can be found in the data supplement. The cardiac performance of heterozygous mice and wild-type littermates was assessed by physiological studies, including echocardiography (Vevo 770, Visual Sonics) and induction of hypertrophy by two weeks continued angiotensin II (Ang II) and isoproterenol (ISO) application via ALZET mini pumps, which are described in detail in the online data supplement.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Differences between experimental groups were analyzed by use of an adjusted student t test or ANOVA for repeated measures, as appropriate. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Values of P<0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 Ttn insertion mutation results in early embryonic lethality in mice

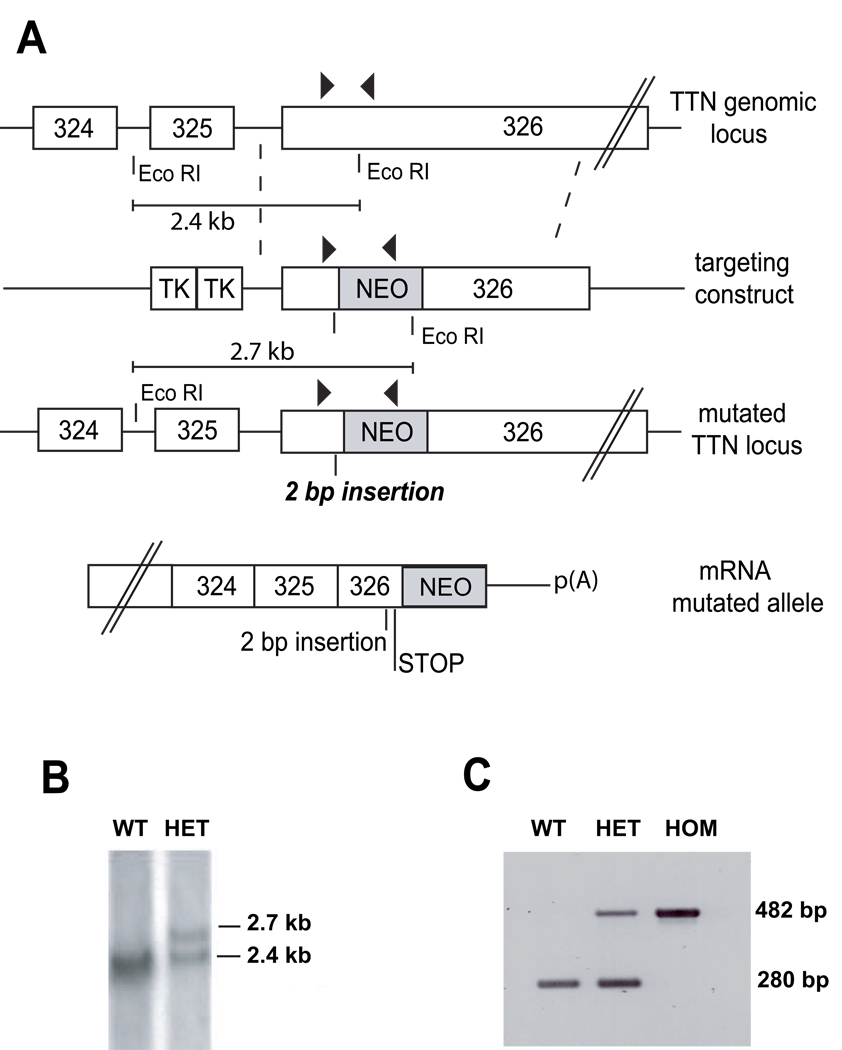

The 2-bp TTN insertion mutation (c.43628insAT), which was previously identified in a family suffering from DCM [3], was introduced into mouse ES cells by homologous recombination. The targeting vector was designed as shown in Figure 1A. The human exon 326 AT-insertion mutation was included at the corresponding site of the mouse genome, followed by a neomycin resistance cassette. Homologous recombination events were identified by Southern blot analyses (Fig. 1B), and a mouse line with stable transmission of the mutated Ttn allele was obtained for subsequent generations. Genotypes were determined by PCR and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B,C). Crosses between heterozygous mice produced no homozygous offspring, implying that homozygous embryos died during embryogenesis.

Figure 1. Generation of Ttn knock-in mouse by gene targeting.

(A) Depiction of the mouse Ttn genomic locus, the targeting vector, the allele resulting from homologous recombination, and the mutant mRNA allele. Exons are indicated as white boxes, and 324–326 (above) refers to the numbers of titin exons in the human TTN sequence. Arrowheads denote the positions of primers used for PCR genotyping. The position of the 2-bp (AT) insertion mutation is designated.

(B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA digested with EcoRI produced bands of the expected sizes (2.7 kb and 2.4 kb) in heterozygous animals.

(C) PCR-based genotyping. PCR products derived from the wild-type (WT) and homozygous (HOM) alleles were 280bp and 482bp, respectively. Heterozygous animals (HET) showed both the WT and HOM alleles. Embryos were genotyped from the yolk sack.

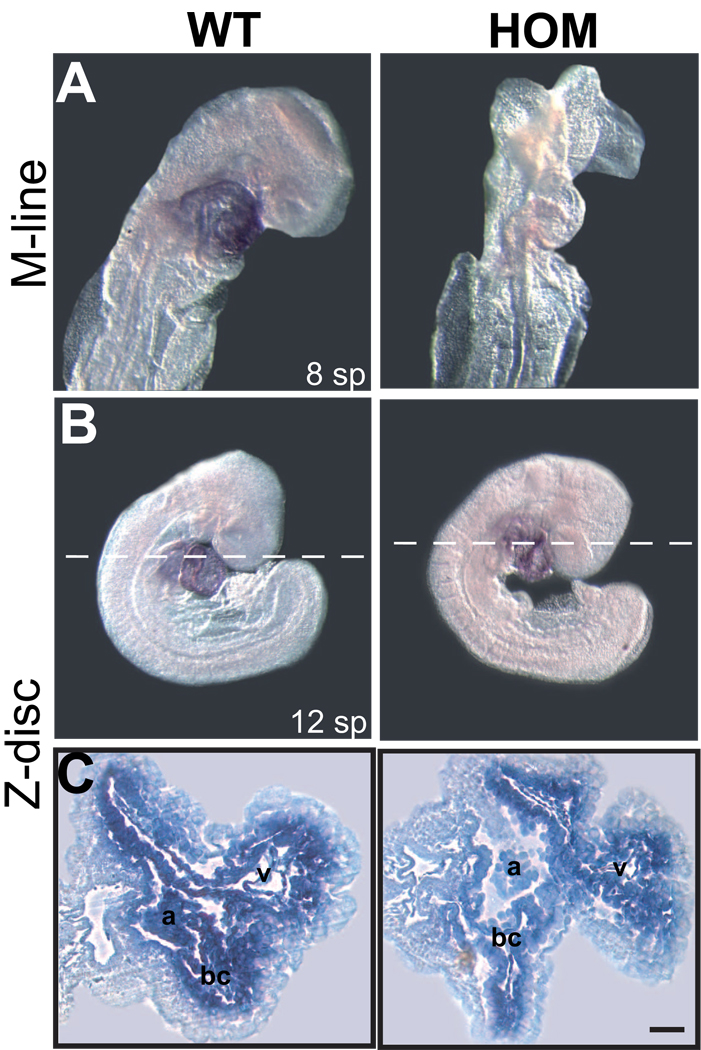

To determine the day of embryonic lethality, embryos from different developmental stages were genotyped by PCR (Fig. 1C). None of the 126 embryos between E10.5–E13.5 was identified as a homozygous mutation carrier (69 heterozygotes, 29 wild-types, Table 1), whereas resorption bodies as well as homozygous embryos could be detected at E9.5. However, the homozygous embryos at E9.5 were poorly developed and smaller in size compared to the heterozygous embryos, suggesting that resorption of these embryos had been initiated by this developmental stage. At E8.5, homozygous embryos were similar to the expected Mendelian ratio of 1:2:1 (Table 1) and normal in size and appearance compared to wild-type and heterozygous animals. To investigate titin mRNA expression in wild-type and homozygous embryos during early cardiac development, whole-mount in situ hybridization at E8.5 (8 somite pairs) and E8.75 (12 somite pairs) was performed using antisense probes directed against the Z-disc and the M-line region (exon 358, located close to the 3’ end of the murine titin gene). In wild-type embryos, titin mRNA expression was detectable with both probes at all investigated stages [20], whereas the M-line probe did not hybridize to homozygous embryos (Fig. 2A,B). Transverse sections at the 12 somite stage showed no fundamental differences in heart formation between wild-type and homozygous embryos. Cardiac looping was observed, suggesting that Ttn did not affect early heart-looping processes. However, the homozygous heart region appeared enlarged and demonstrated a pericardial edema (Fig. 2C). Additional histological sections of the developing heart of homozygous embryos at E8.5 confirmed these observations by demonstrating slightly enlarged common ventricles with thinner ventricular walls, loosely packed endocardial cells, and pericardial edema in comparison to wild-type embryos. At E9.0, the process of dissolving the heart was much more advanced, the ventricles and atria appeared smaller and without a proper layer structure, and the pericardial edema had increased (Fig. 2D–G). Homozygous embryos at the same stage examined by scanning electron microscopy confirmed these observations. The heart region appeared edematous and the whole embryo, especially the head region, was smaller than wild-type embryos (Fig. 2H–K). Remaining homozygous embryos at E9.5 were profoundly macerated, without any detectable heart structures.

Table 1.

Viability of embryos resulting from heterozygous intercrosses.

| Stage | WT (+/+) | HET(+/−) | HOM(−/−) | Resorbed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E8.5 | 6 (22%) | 14 (52 %) | 7 (26%) | 0 (0%) | 27 |

| E9.5 | 13 (24%) | 25 (46%) | 10 (19%) | 6 (11%) | 54 |

| E10.5 | 4 (18%) | 13 (59%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (23%) | 22 |

| E11.5 | 13 (23%) | 34 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (18%) | 57 |

| E12.5 | 10 (37%) | 12 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19%) | 27 |

| E13.5 | 2 (10%) | 10 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (40%) | 20 |

Embryonic stage is indicated as the embryonic day after coitum. Completely resorbed bodies occur from E9.5, indicating a very early development defect. All embryos were counted at E8.5 by ultrasound and genotyped at the stage as indicated.

Figure 2. Defects in heart development at E9.0 caused by unformed sarcomeres in homozygous Ttn knock-in embryos.

(A–C) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Ttn Z-disc (A) and Ttn M-line (B) in wild-type (WT) and homozygous (HOM) embryos. Hearts are stained in all wild-type embryos, whereas the M-line probe in homozygous embryos does not show a signal. Note the intact cardiac looping in the homozygous embryo (A). Transverse sections (C) in two sections planes with dotted lines in B.

(D–G) Histological analysis of transverse sections through the forming heart of WT and HOM embryos at E8.5 and E9.0 demonstrates an enlarged common ventricle (v) with reduced ventricular wall thickness, loosely packed endocardial cells, and pericardial edema (E,G) in HOM embryos.

(H–K) Scanning electron microscopy of WT and HOM animals at E9.0 confirmed the observation of an enlarged heart region in HOM animals (I,K).

(L–O) Ultrastructural analysis of cardiac sarcomere maturation in WT and HOM hearts showed appropriate myofibrils at E8.5. At E9.0, sarcomeres had been assembled in WT hearts (N), in contrast to titin-deficient hearts, which demonstrated no striation or sarcomere formation (O).

sp, somite pairs; v, common ventricular chamber; bc, bulbus cordis; a, atrial chamber; Z, Z-disc; M, M-band; J, cellular junctions. Scale bars, (C) 100 µm (D)–(K) 200µm; (L)–(O) 1 µm.

The defects in heart development of homozygous embryos at E8.5 correlate with the expression pattern of titin and the development of muscle striation in the embryonic heart, because expressed titin dots are observed in E8.25 hearts, followed by filament expression at E8.5 and the first muscle striation at E9.0 [21]. To further determine the changes in heart muscle striation and sarcomere assembly in homozygous hearts, electron microscopy analysis of ventricular myocardium from E8.5 and E9.0 homozygous and wild-type embryos was carried out. In wild-type myocardium, the myofibrils exhibited an organized sarcomere structure with clearly distinguishable Z-discs and M-lines. In contrast, homozygous myocardium of the same stage (E9.0) showed no striations, indicating that the sarcomeres had not been assembled (Fig. 2L–O). To determine the functional consequence of unformed sarcomeres, we examined wild-type and homozygous embryos between E8.75 and E9.25 by ultrasound (data not shown). In wild-type embryos, the heart started to beat at E8.75, whereas heartbeats were never observed in homozygous embryos, suggesting that initiation of cardiac function required an organized striated muscle architecture.

3.2 Posttranslational degradation of the truncated titin protein

Mice heterozygous for the mutated titin allele were viable and fertile, and they grew to adulthood without obvious abnormalities in general health and appearance.

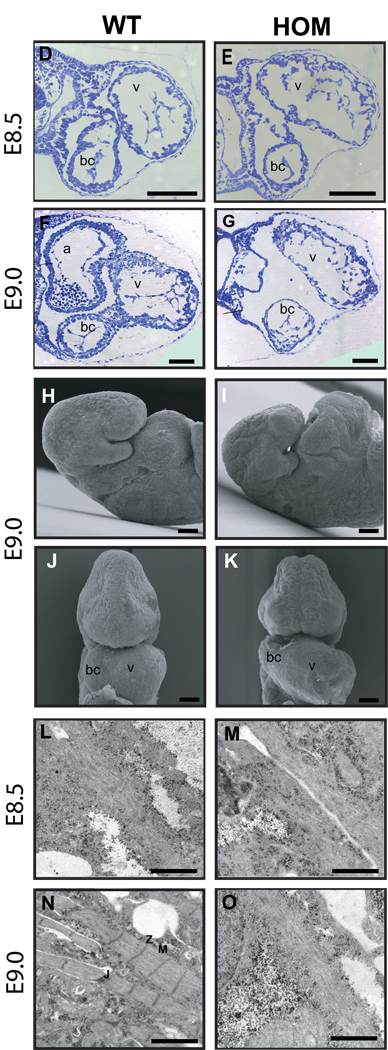

In order to detect the predicted truncated protein in heart muscle tissue extracted from heterozygous animals, we performed Western blots using anti-titin antibodies with binding sites c-terminal (Z1Z2) and n-terminal (M8M9) of titin. Although the truncated protein (~2.0 MDa) was detectable in hearts of heterozygous mice, the very small amount of approximately 1% indicates a posttranslational degradation or modification process of the mutated titin protein. Furthermore major differences in wild-type protein expression were not observed (titin:myosin protein ratio: WT 0.27; HET 0.21; p>0.1; Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Titin expression analysis in heterozygous mice.

(A) SDS agarose gel analysis of heart muscle tissue from unstressed (− Ang II) and stressed (+ Ang II) heterozygous (HET) and wild-type (WT) mice revealed in HET’s of both groups an extra band consistent with a small amount of a truncated protein (~2.0 MDa) which is detectable with anti-Z1/Z2, but not with anti-M8M9. Note no obvious difference in wild-type titin protein amounts between HET’s and WT’s. T1 undegraded titin, T2 degraded titin, Ang II angiotensin II.

(B) Real-time PCR analysis of titin mRNA expression in hearts of heterozygous mice compared to their wild-type littermates. Primer pairs specific for Z-disc titin (amplifying both alleles) and M-line titin (amplifying only the wild-type allele) were used for PCR. Titin mRNA levels were 76±11% measured with the M-line probe and 131±24% measured with the Z-disc probe (*p<0.05), indicating a partial compensation (full compensation would result in 100% mRNA expression with the M-line and 150% with the Z-disc probe relative to mRNA expression levels of wild-type littermates).

RT-PCR using oligonucleotides specific for the wild-type or the mutant titin allele, respectively, showed that both alleles were stably expressed at mRNA level in heterozygous hearts. To further quantify cardiac titin mRNA expression, we performed real-time RT-PCR analysis with oligonucleotides specific for titin’s Z-disc portion (amplifying both alleles), or with allele-specific oligonucleotides (amplifying only the wild-type allele of titin’s M-line portion). We found that wild-type titin mRNA transcription was elevated in the presence of the mutant titin allele, although this compensation was incomplete (see Fig. 3B: 76±11% wild-type M-line expression as experimentally determined vs. theoretically expected 50% allele-specific mRNA expression; p<0.05).

In summary, our mRNA and protein expression studies on heterozygous hearts suggest that the mutated allele is unstable, leading to an up-regulation of wild-type titin mRNA and protein.

3.3 Heterozygous mice demonstrate normal cardiac function and mechanical properties

Titin filaments are major determinants for muscle elasticity and passive tension. To investigate the impact of titin protein changes on mechanical properties in our heterozygous model, we measured active and passive tension as well as the contribution of titin and collagen to passive tension in skinned ventricular papillary muscle fibers of 12 months old wild-type and heterozygous mice (n=6 for each group). Maximal active tension was not different (48.7±5.3mN/mm2 vs. 39.2±1.9mN/mm2 p<0.15) (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Passive tension was measured by stretching the fibers to a SL of 2.3 µm and then holding the length constant for 5 min. to measure steady-state passive tension. Cardiac muscle fibers from heterozygous mice showed no significant change in peak passive tension at SL of 2.3 µm (p<0.44) nor in steady state passive tension (p<0.35) compared with those from wild-type mice (Suppl. Fig. 1B;C), suggesting that there is no difference in the passive viscoelastic properties of both groups. Passive myocardial tension is known to be largely the result of titin and collagen [6]. To assess the passive tension due to titin we used high concentrations of KCl/KI to cause disassociation of the thin and thick filaments, respectively, which also disallows passive forces produced by titin due its association with those filaments. However, we did not detect any difference between wild-type and heterozygous animals either in titin`s or in collagen’s contribution to passive forces (Suppl. Fig. 1D).

Our in vitro assessment of mechanical properties of heterozygous cardiac muscle could be confirmed by in vivo echocardiography. Neither systolic cardiac function and left ventricular diameters nor diastolic filling parameters were significantly different between both genotypes under resting conditions (Suppl. Table 1).

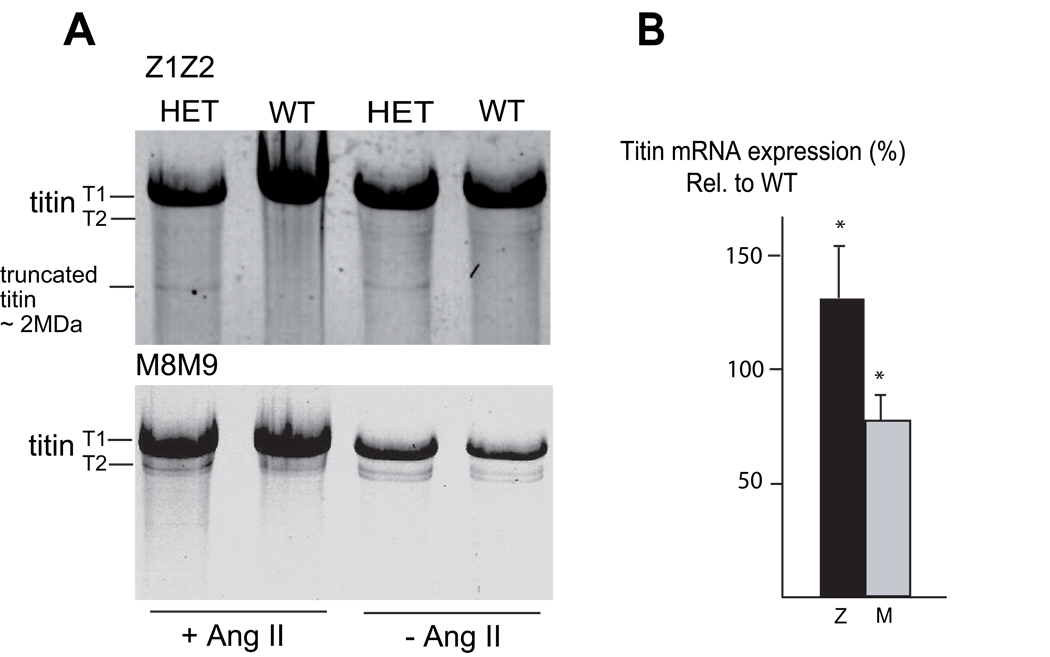

3.4 Stress-induced left ventricular dilatation with impaired systolic function in heterozygous mice

To assess cardiac performance under chronic cardiac stress, the response of heterozygous Ttn knock-in mice to pathological cardiac hypertrophic stimuli was tested by angiotensin II (Ang II) application for 14 days via osmotic mini-pumps at doses that induce arterial hypertension (1.4 mg/kg). Heterozygous animals showed a similar hypertrophic response compared to wild-type littermates after one week of Ang II infusion. The ventricular ejection fraction and fractional shortening increased and ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters decreased in both groups.

After two weeks of Ang II infusion ejection fraction and fractional shortening increased in wild-type animals from 54.4±6.8% at baseline to 60.8±3.6% (p<0.001) and from 28.2±4.5% at baseline to 33.4±2.8% (p<0.001), respectively. Although systolic function improved after one week of Ang II treatment in heterozygous mice by an increase in ejection fraction from 53.2±6.5% to 56.0±8.2% and in fractional shortening from 27.4±4.3% to 31.9±6.1%, it deteriorated significantly after two weeks of treatment: ejection fraction fell to 47.3±7.8% (p<0.001) and fractional shortening was reduced to 23.9±4.6% (p<0.001). Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) decreased in Ang II treated wild-type animals over two weeks from 4.5±0.3 to 4.0±0.4mm (p<0.05). Although heterozygous mice showed also decreased LVEDD after one week of Ang II treatment (from 4.5±0.2 to 4.0±0.5mm), left ventricular size started to increase after another week of Ang II treatment to 4.5±0.4mm (p<0.05). These data indicate a negative remodelling effect after prolonged exposure to Ang II in animals heterozygous for the Ttn insertion mutation when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4A, Table S2).

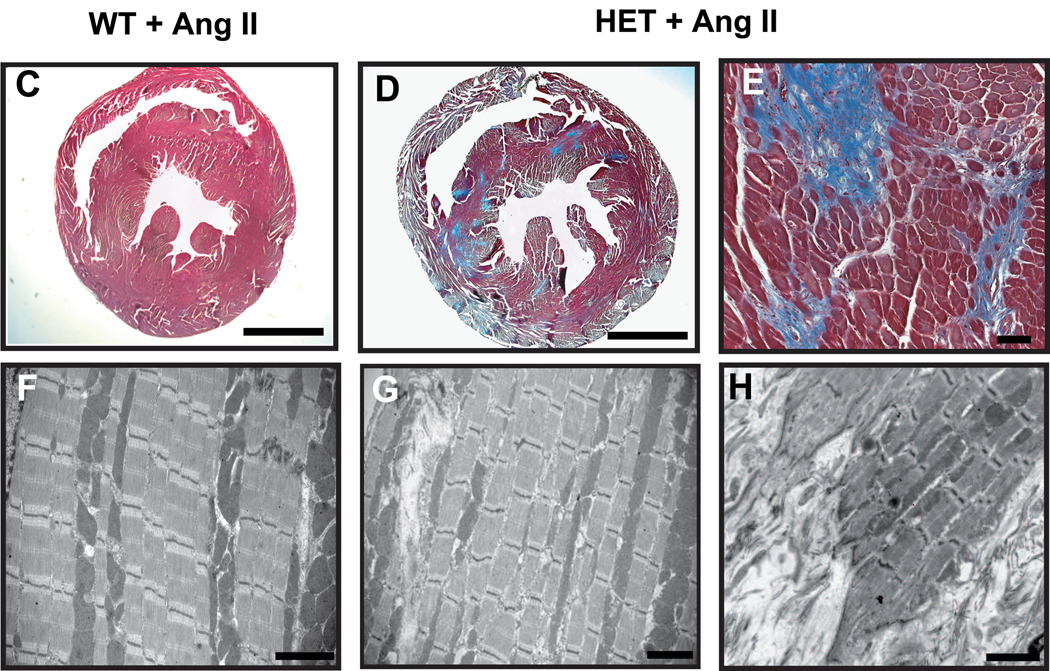

Figure 4. Stressed heterozygous Ttn knock-in mice develop features of DCM.

(A) Echocardiographic assessment before, after one week, and after two weeks of angiotensin II (Ang II) application. After one week, both genotypes showed cardiac hypertrophy, as observed in end-diastolic dimensions (LVEDD) and enhanced systolic contractility (fractional shortening). After two weeks of Ang II application, the hypertrophy in wild-type (WT) animals is increased, whereas heterozygous mice (HET) develop left ventricular dilatation (**p<0.05) with impaired systolic function (*p<0.001). Compared to baseline conditions fractional shortening is decreased (*p<0.001) in heterozygous animals.

(B) Quantification of interstitial myocardial fibrosis after application of two weeks of Ang II or one week of isoproterenol (ISO). The development of fibrosis after Ang II/ISO application administration is pronounced in heterozygous animals (*p<0.01; † p<0.05) compared with their wild-type littermates.

(C–H) Myocardial histology and electron microscopy of mouse hearts after Ang II application. Representative sections from hearts of wild-type and heterozygous animals after two weeks of Ang II application stained with Masson’s trichrome (C–E). Note the increased level of fibrosis in heterozygous hearts. Electron microscopy of heterozygous ventricles demonstrates regions of preserved sarcomere assembly (G) and interstitial fibrosis (G, arrowhead and H). Note areas of increased fibrosis and infiltration into the sarcomere (H).

Scale bars: (C) and (D) 2 mm; (E) 40µm; (F–H) 2 µm

In addition to these functional observations, the development of interstitial fibrosis induced by Ang II was assessed by light microscopy. Two weeks of treatment with Ang II led to significantly increased fibrosis in heterozygous mice vs. wild-type controls. Semi-quantitative analysis of the extent of cardiac interstitial fibrosis showed significantly more trichrome Masson staining signals in heterozygous animals than in wild-type littermates (11.95±2.8% vs. 3.7±1.1%; p<0.001; Fig. 4B,C–E). However, the sarcomere structure was preserved, with regular longitudinal alignment of myofibrils and the presence of intact Z–discs observed by electron microscopy (Fig. 4F–H) Particularly noticeable, but only in areas with apparent massive fibrosis, we found myofibrillar disarray and partial loss of myocyte structure in the transition zone, as seen in Fig. 4H.

To exclude an Ang II–specific effect, cardiac performance was also assessed using the beta-receptor agonist isoproterenol (ISO). Continuous infusion of ISO at a dose of 30mg/kg via osmotic mini-pumps over one week caused a similar extent of cardiac hypertrophy in heterozygous mice and controls. However, heterozygous mice developed dilated cardiomyopathy, with significant enlargement of left ventricular cardiac chambers, a reduction in the ejection fraction (38.6±7.0% vs. 52.8±9.1%; p<0.01), and fractional shortening (23.7±5.7% vs. 34.2±7.6%; p<0.01) after one week of ISO application compared to wild-type animals (Table S3). Blood pressure analysis of Ang II– and ISO-treated animals demonstrated no significant differences between heterozygous and wild-type mice (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Despite considerable progress in elucidating the genetic etiology of familial DCM, the pathogenetic processes leading to heart failure still remain largely obscure. Given the large number of DCM causing mutations and the diverse nature of the respective disease genes, multiple functional and/or structural pathways are likely to be perturbed in DCM. Here, we generated a knock-in mouse model that includes a 2-bp insertion mutation in A-band titin, corresponding to the human DCM causing mutation, to elucidate titin’s role during disease development of familial DCM. While loss of Ttn in homozygous mice caused developmental defects in sarcomere formation, leading to early embryonic lethality at E9.0, precluding further studies, heterozygous mice were viable and could be characterized in detail. Protein expression analysis suggests a compensation of the mutant titin allele by up-regulation of wild-type titin leading to proper cardiac function without obvious structural and mechanical alterations of cardiomyocytes under resting conditions. In response to cardiac stress, the heart de-compensates, resulting in left ventricular dilatation, systolic dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis.

Our failure to detect homozygous offspring for the mutant titin demonstrates the requirement of the Z-disk to M-line titin spanning system during development. Although homozygous embryos could be observed at early embryonic stages (before E9.5), those animals showed an arrest in heart development and no sarcomere formation. Titin has been proposed to act as a molecular scaffold for sarcomere formation and assembly through its ability to multimerize into filaments extending throughout the muscle fiber [7,8]. Our results provide evidence that the removal of titin’s M-line region leads to unformed sarcomere structures, resulting in embryonic hearts that never beat. Titin has been reported to be initially expressed at E8.25 in the muscle tissue, titin filaments appeared at E8.5, and muscle striation could be observed at E9.0 [21]. Our data confirm these findings and demonstrate a chronological relationship between titin expression, sarcomere formation, and embryonic lethality due to non-beating hearts.

The TTN 2bp-insertion mutation has been reported in a large family with autosomal dominant DCM causing congestive heart failure with variable phenotypic expression and age of onset in affected patients [3]. Our heterozygous knock-in mice did not demonstrate major changes in cardiac morphology or function, neither in 6 months nor one-year old animals, most likely because the wild-type allele is up-regulated and only trace amounts of mutant titin protein can be detected. Consistent with this, studies on skinned myocardium confirmed normal biomechanical properties of myofibrils from heterozygous hearts. Apparently, the minimal amount of a mutant truncated protein (roughly 1% when compared to full-length wild-type titin) is insufficient to cause a cardiac disease phenotype in mice under resting conditions. These findings are consistent with the protein analysis of a cardiac biopsy sample obtained from a patient with the 2-bp AT-insertion mutation of TTN: Here, SDS-agarose gel analysis also did not show a truncated titin protein (Suppl. Fig. 2), indicating either proteolytic processing or that other yet unknown post-transcriptional editing mechanisms must prevent the translation or incorporation of mutant titin’s into myofibrils [22,23].

Because titin has been suggested to play a role in biomechanical sensing and signalling [24–28], we performed extensive expression studies using known titin ligands involved in those functions, but we did not find any significant changes in our un-stressed heterozygous mice (Suppl. Fig. 3). Although we cannot exclude dysregulation of a yet unknown binding partner, the remaining truncated protein as well as the up-regulated wild-type titin protein seems to be sufficient to preserve myofibrillar signal transduction. Presumably, these functions are not involved in the pathogenesis of familial DCM, at least with respect to our mouse model.

To test the phenotype of our mice under chronic myocardial stress, we induced cardiac hypertrophy by activating angiotensin receptors with Ang II [29]. As expected, both genotypes developed cardiac hypertrophy after one week of Ang II application. However, after two weeks, hypertrophy in wild-type animals was further increased, whereas their heterozygous littermates showed left ventricular dilatation with impaired systolic function and extended myocardial fibrosis. Although the sarcomere structures were not altered in general, in the transition zones between fibrotic tissue and myocytes we observed partial myocyte loss and myofibrillar disarray (Fig. 4H), which presumably contributes to cardiac remodelling processes leading to the development of dilated cardiomyopathy. Future studies are required to establish the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of titin in this process.

A remaining puzzle lies in the absence of any detectable skeletal muscle phenotype in patients carrying the DCM causing TTN mutation, which is expressed in cardiac and non-cardiac muscle isoforms. To characterize skeletal muscle function in our mouse model, heterozygous mice underwent a detailed gait analysis program that is able to detect clinically in-apparent stages of skeletal muscle disorder [30]. Nevertheless, we did not find a skeletal muscle phenotype in titin-deficient mice. Consistent with the results in heart muscle tissue, titin ligands were equally expressed in both genotypes, and titin mRNA and protein expression patterns were similar compared to cardiac tissue in heterozygous animals (data not shown).

In summary, our titin knock-in mouse that truncates titin within its central A-band portion caused homozygous, early embryonic lethality, demonstrating the requirement of a Z-disk to M-line spanning system during mammalian muscle development. In addition it is possible that part of the titin molecule that is missing performs a function that is independent of titin’s Z-disk to M-line spanning function. In heterozygous mice, features of the human DCM phenoptype are mimicked under cardiac stress. Therefore, this mouse model may contribute in the future to the development of therapeutic strategies for combating genetic heart diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Liebner, M. Taube, W.P. Schlegel, J. Nissen for expert technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Stiftung für Herzforschung (F/26/02), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GE 1222/1-2; La668/7-2 and 13-1), and NIH (HL62881).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available online.

References

- 1.Dec GW, Fuster V. Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1564–1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412083312307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morita H, Seidman J, Seidman CE. Genetic causes of human heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:518–526. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerull B, Gramlich M, Atherton J, McNabb M, Trombitás K, Sasse-Klaassen S, et al. Mutations of TTN, encoding the giant muscle filament titin, cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;30:201–204. doi: 10.1038/ng815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerull B, Atherton J, Geupel A, Sasse-Klaassen S, Heuser A, Frenneaux M, et al. Identification of a novel frameshift mutation in the giant muscle filament titin in a larger Australian family with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Mol M. 2006;84:478–483. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh M, Takahashi M, Sakamoto T, Hiroe M, Marumo F, Kimura A. Structural analysis of the titin gene in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of a novel disease gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262(2):411–417. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granzier HL, Labeit S. The giant protein titin. A major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:284–295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117769.88862.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labeit S, Komerer B. Titins: giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science. 1995;270:293–296. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linke WA. Sense and stretchability: the role of titin and titin-associated proteins in myocardial stress-sensing and mechanical dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagueh SF, Shah G, Wu Y, Torre-Amione G, King NMP, Lahmers S, et al. Altered titin expression, myocardial stiffness, and left ventricular function in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110:155–162. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135591.37759.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng J, Raddatz K, Molkentin JD, Wu Y, Labeit S, Granzier H, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy and reduced contractility in hearts deficient in the titin kinase region. Circulation. 2007;115:743–751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.645499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotthardt M, Hammer RE, Hübner N, Monti J, Witt CC, McNabb M, et al. Conditionally expression of mutant M-line titin results in cardiomyopathy with altered sarcomere structure. J Biol Chem. 2002;278:6059–6065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radke M, Peng J, Wu Y, McNabb M, Nelson OL, Granzier H, et al. Targeted deletion of titin N2B region leads to diastolic dysfunction and cardiac atrophy. PNAS. 2007;104:3444–3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608543104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinert S, Bergmann N, Luo X, Erdmann B, Gotthardt M. M line-deficient titin causes cardiac lethality through impaired maturation of the sarcomere. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(4):559–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Person V, Kostin S, Suzuki K, Labeit S, Schaper J. Antisense oligonucleotide experiments elucidate the essential role of titin in sarcomerogenesis in adult rat cardiomyocytes in long-term culture. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3851–3859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu X, Meiler SE, Zhong TP, Mohideen M, Crossley DA, Burggren WW, et al. Cardiomyopathy in zebrafish due to mutation in an alternatively spliced exon of titin. Nat Genet. 2002;30:205–209. doi: 10.1038/ng816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller G, Musa H, Gautel M, Peckham M. A targeted deletion of the C-terminal end of titin, including the titin kinase domain, impairs myofibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4811–4819. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren CM, Krzesinski PR, Greaser ML. Vertical agarose gel electrophoresis and electroblotting of high-molecular-weight proteins. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:1695–1702. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granzier HL, Irving TC. Passive tension in cardiac muscle: contribution of collagen, titin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Biophys J. 1995 Mar;68:1027–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80278-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granzier H, Helmes M, Trombitás K. Nonuniform elasticity of titin in cardiac myocytes: a study using immunoelectron microscopy and cellular mechanics. Biophys J. 1996 Jan;70(1):430–442. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolmerer B, Olivieri N, Witt CC, Herrmann BG, Labeit S. Genomic organization of M line titin and its tissue-specific expression in two distinct isoforms. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:556–563. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaart G, Viebahn C, Langmann W, Ramaekers F. Desmin and titin expression in early postimplantation mouse embryos. Development. 1989;107:585–596. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witt SH, Granzier H, Witt CC, Labeit S. J Mol Biol. 2005;350(4):713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller G, Musa H, Gautel M, Peckham M. A targeted deletion of the C-terminal end of titin, including the kinase domain, impairs myofibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4811–4819. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granzier H, Labeit S. Structure-function relations of the giant elastic protein titin in striated and smooth muscle cells. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:740–755. doi: 10.1002/mus.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raju R, Dalakas MC. Absence of upregulated genes associated with protein accumulations in desmin myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:386–388. doi: 10.1002/mus.20680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Biesiadecki BJ, Jin JP. Selective deletion of the NH2-terminal variable region of cardiac troponin T in ischemia reperfusion by myofibril associated mu-calpain cleavage. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11681–11694. doi: 10.1021/bi060273s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller MK, Granzier H, Ehler E, Gregorio CC. The sensitive giant: the role of titin-based stretch sensing complexes in the heart. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lange S, Xiang F, Yakovenko A, Vihola A, Hackman P, Rostkova E, et al. The kinase domain of titin controls muscle gene expression and protein turnover. Science. 2005;308:1599–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1110463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harada K, Komuro I, Shiojima I, Hayashi D, Kudoh S, Mizuno T, et al. Pressure overload induces cardiac hypertrophy in angiotensin II type 1A receptor knockout mice. Circulation. 1998;97:1952–1959. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.19.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wooley CM, Sher RB, Kale A, Frankel WN, Cox GA, Seburn KL. Gait analysis detects early changes in transgenic SOD1(G93A) mice. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:43–50. doi: 10.1002/mus.20228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.