Patient 1

A 54-year-old man presented with a 3-day history of difficulty speaking and an unsteady gait after having a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. He had been taking oral metronidazole for bronchiectasis for 2 months before presentation (estimated cumulative dose of about 60 g). His medical history included recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. He had no family history of neurologic disorders.

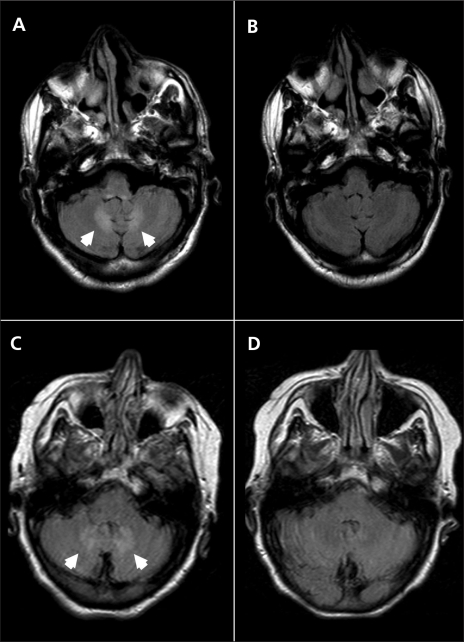

Neurological examination showed cerebellar dysarthria, bilateral dysmetria and an ataxic wide-based gait. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. The results of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient’s brain were reported to be normal, although, in retrospect, faint hyperintensities within the dentate nuclei could be seen on the T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scans. The patient’s symptoms and signs improved over the next 4 days.

One week later, the patient’s dysarthria and ataxia (gait and appendicular) worsened, and he was admitted to hospital. Repeat T2-weighted FLAIR MRI showed obvious bilateral symmetric hyperintensities within the dentate nuclei of the cerebellum (Figure 1A). The results of a thorough work-up for cerebellar disorders were negative: nutritional causes (vitamin B12 and vitamin E deficiencies) and genetic disorders (Friedreich ataxia, spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis) were ruled out. About 1 month after admission, phenytoin was initiated after a second seizure.

Figure 1.

Axial magnetic resonance images of the first patient’s brain while taking metronidazole (A) and after discontinuation of metronidazole (B), and of the second patient’s brain while on metronidazole (C) and after disconntinuation of metronidazole (D). Cerebellar dentate hyperintensities (arrowheads) on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging are visible for both patients while taking metronidazole (A, C), which resolved after the drug was stopped (B, D).

At the initial presentation, the cause of the patient’s difficulties was not recognized, and he continued to take metronidazole for bronchiectasis until this therapy was discontinued about 2 months later. At a follow-up examination 3 months after discontinuation of metronidazole, the patient’s cerebellar syndrome had resolved. A repeat MRI scan of the patient’s brain showed complete resolution of signal changes within the dentate nuclei (Figure 1B).

Patient 2

A 72-year-old woman was admitted with pain in her left leg and flank from an intra-abdominal abscess. Her medical history included coronary artery disease with a remote myocardial infarction and subsequent coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Her history also included hypothyroidism, a left nephrectomy for a renal abscess and a remote history of smoking.

About 3 weeks after initiation of metronidazole (500 mg twice a day, cumulative dose of about 25 g), she developed a cerebellar syndrome with cerebellar dysarthria, dysmetria and gait ataxia. An MRI scan of her brain taken about 2 months after the onset of this syndrome showed abnormal signal within the cerebellar dentate nuclei bilaterally on T2-weighted FLAIR imaging (Figure 1C), which was virtually identical to the findings for patient 1. Based on these findings, metronidazole toxicity was suspected, and the drug was discontinued. The patient’s symptoms gradually resolved over the next few weeks. An MRI scan of her brain taken 1 month after metronidazole was stopped showed complete resolution of the cerebellar dentate lesions (Figure 1D). The patient died 2 months later of unrelated causes.

Discussion

Metronidazole is an antibiotic widely used in clinical practice, but case reports1–4 have shown that both peripheral and central nervous system–associated neurotoxicity can occur with metronidazole use (Box 1). Peripheral neuropathy is the most common adverse neurologic effect caused by metronidazole. Most of the adverse effects are reversible within weeks of discontinuation of treatment.

Box 1.

Neurologic complications associated with the use of metronidazole

Cerebellar syndrome

Encephalopathy

Seizures

Autonomic neuropathy

Optic neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy

A reversible cerebellar syndrome with characteristic cerebellar dentate nuclei lesions on T2-weighted FLAIR MRI scans has been attributed to metronidazole use, as described for our 2 patients and by others.4–7 Patients usually present with cerebellar dysarthria and ataxia that may occasionally fluctuate, as in our first patient. The duration of treatment with metronidazole before cerebellar symptoms manifest is variable, ranging from 28 days6 to 3 months,7 and cumulative doses range from 25 g (as in our second patient) to 90 g.7 Patients usually experience complete resolution of the symptoms after discontinuation of metronidazole, sometimes within a few days. To our knowledge, there have been no published reports of cerebellar syndrome associated with metronidazole that have not improved after discontinuation of metronidazole therapy. Our patients’ symptoms and signs resolved within weeks of stopping metronidazole. The MRI changes also resolved in both patients, thereby implicating the drug as the causative agent.

The reversible cerebellar syndrome described by us and by others is correlated with striking and symmetric MRI T2–FLAIR hyperintensities within the dentate nuclei of the cerebellum. Other areas of the brain may also be affected by metronidazole use, including the midbrain, pons, medulla, corpus callosum and other brainstem regions.8 The cerebellar dentate nuclei is the most commonly affected area.

The mechanism of action of metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity on the central and peripheral nervous systems is not well understood. Proposed mechanisms include binding of metronidazole to RNA, DNA and inhibitory neurotransmitters, as well as inducing both vasogenic and cytotoxic edema.6 Metronidazole is structurally similar to the thiazole precursor of thiamine and could thereby lead to a reduction in thiamine absorption by acting as a thiamine analog.9

The propensity to develop these adverse effects is poorly understood. There may be some relation to dose, but in both of our patients, the administered dose was within the recommended range. Patient 2 developed the syndrome after a relatively low cumulative dose of only 25 g, which is at the low end of the range of doses associated with cerebellar syndrome. Synergistic toxicity with other medications is also possible.10

The neurotoxic adverse effects of metronidazole continue to be underrecognized despite its widespread use. Our recognition of the cause for the dentate lesions in our first patient was delayed until one of us (S.F.) came across a case description in a specialty journal. Recognition of the syndrome prompted discontinuation of metronidazole for patient 2.

Adverse side effects from medications, particularly when unexpected and serious, should be reported to the Canada Vigilance Program (www.healthcanada.gc.ca/medeffect).

Key points

Cerebellar syndrome, encephalopathy, seizures and autonomic, optic and peripheral neuropathies have been associated with the use of metronidazole.

Cerebellar syndrome usually begins gradually within several months of taking metronidazole.

Once the medication is discontinued, the syndrome generally improves within days and resolves within several weeks.

This syndrome is associated with prominent reversible bilateral cerebellar dentate nuclear hyperintensities on T2-weighted magnetic resonance images.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Previously published at www.cmaj.ca

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGrath NM, Kent-Smith B, Sharp DM. Reversible optic neuropathy due to metronidazole. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35:585–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobson-Webb LD, Roach ES, Donofrio PD. Metronidazole: newly recognized causes of autonomic neuropathy. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:429–31. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210051201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frytak S, Moertel CH, Childs DS. Neurologic toxicity associated with high-dose metronidazole therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:361–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-3-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel K, Green-Hopkins I, Lu S, et al. Cerebellar ataxia following prolonged use of metronidazole: case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:e111–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodruff BK, Wijdicks EFM, Marshall WF. Reversible metronidazole-induced lesions of the cerebellar dentate nuclei. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:68–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200201033460117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusumi RK, Plouffe JF, Wyatt RH, et al. Central nervous system toxicity associated with metronidazole therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:59–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seok JI, Yi H, Song YM, et al. Metronidazole-induced encephalopathy and inferior olivary hypertrophy: lesion analysis with diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient maps. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1796–800. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim E, Na DG, Kim EY, et al. MR imaging of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy: lesion distribution and diffusion-weighted imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1652–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapoor K, Chandra M, Nag D, et al. Evaluation of metronidazole toxicity: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1999;19:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toumi S, Hammouda M, Essid A, et al. Metronidazole-induced reversible cerebellar lesions and peripheral neuropathy [French] Med Mal Infect. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.11.007. Epub 2008 Dec. 30 ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]