Abstract

The totality of data indicate that the window of opportunity for reducing mortality and coronary heart disease (CHD) is initiation of hormone therapy (HT) within 6 years of menopause and/or by 60 years of age and continued for 6 years or more. Additionally, the risks of HT are rare (<1/1,000) especially in younger postmenopausal women and comparable to other primary prevention therapies. In fact, as randomized controlled trial results accumulate, the more they look like the consistent observational data that young postmenopausal women with menopausal symptoms who use HT for long periods of time have lower rates of mortality and CHD than comparable postmenopausal women who do not use HT.

Introduction

The consistency of observational data demonstrating a reduction of coronary heart disease (CHD) with exogenous postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) is unparalleled by any other potential therapy for the primary prevention of CHD in women. The consistency across observational studies led to formulation of the estrogen cardioprotective hypothesis that operated un-tested until the 1990's when a series of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were undertaken to test this hypothesis. These RCTs demonstrated 3 salient points: 1) HT reduces total mortality while potentially reducing CHD in younger but not in older postmenopausal women; 2) duration of HT is important in expressing the benefits on total mortality and CHD; and, 3) the risks of HT are rare especially in younger postmenopausal women and comparable to other primary prevention therapies for CHD. In this chapter, the RCTs designed to study the effects of HT on CHD will be summarized relative to the observational data and placed into perspective with other primary prevention data of CHD in women.

Discordance between RCTs and Observational Studies of HT

Approximately 40 observational studies have consistently shown that both estrogen (1-3) and estrogen plus progestogen (4-8) therapies are associated with a reduced incidence of CHD and total mortality in postmenopausal women. Five RCTs of HT and CHD that have used morbidity and mortality as the trial end point have been published (Table 1). Three of these RCTs were secondary prevention (conducted in women with CHD at randomization) (9-11) and 2 of these trials were primary prevention (conducted in women without pre-existing CHD) (12-15). Additionally, 5 RCTs of HT in postmenopausal women that have used serial arterial imaging as the trial end point have been published; 3 trials used quantitative coronary angiography to measure change in coronary artery lesions (16-18) in women with CHD at randomization and 2 trials used B-mode ultrasound to measure progression of carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT)(Table 2)(19,20).

Table 1.

Randomized Controlled Trials of Coronary Heart Disease and Total Mortality with Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy

| Trial | Sample Size | Mean Age at Entry, y | Time from Menopause, years1 | Treatment | Mean Duration, years | Coronary Heart Disease Relative Risk (95% CI) | Total Mortality Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SECONDARY PREVENTION | |||||||

| HERS (9) | 2,763 | 66.7 | 18.8 | oral CEE 0.625 mg + MPA 2.5 mg | 4.1 | 0.99 (0.80-1.22) | 1.08 (0.84-1.38) |

| PHASE (10) | 255 | 66.5 | >102 | transdermal 17B-E2 alone or sequential NE | 2.6 | 1.29 (0.84-1.95) | not reported |

| ESPRIT (11) | 1,017 | 62.6 | 16 | oral E2-V 2 mg alone | 2.0 | 0.99 (0.70-1.41) | 0.79 (0.50-1.27) |

| PRIMARY PREVENTION | |||||||

| WHI-EP (12,13) | 16,608 | 63.3 | 13.4 | oral CEE 0.625 mg + MPA 2.5 mg | 5.2 | 1.24 (uCI, 1.00-1.54) (aCI, 0.97-1.60) | 0.98 (uCI, 0.82-1.18) (aCI, 0.70-1.37) |

| WHI-E (14,15) | 10,739 | 63.6 | >102 | oral CEE 0.625 mg alone | 6.8 | 0.95 (uCI, 0.79-1.16) (aCI, 0.76-1.19) | 1.04 (uCI, 0.88-1.22) (aCI, 0.81-1.32) |

at randomization

Exact information has not been published

HERS=Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study; PHASE=Papworth HRT Atherosclerosis Study; ESPRIT=Estrogen in the Prevention of Reinfarction Trial; WHI-EP=Women's Health Initiative Estrogen+Progestin Trial; WHI-E=Women's Health Initiative Estrogen Trial CEE=conjugated equine estrogen; MPA=medroxyprogesterone acetate; 17B-E2=17B-estradiol; NE=norethisterone; E2-V=estradiol valerate uCI=unadjusted confidence interval, describes the variability of the point estimate that would arise from a simple trial for a single outcome aCI=adjusted confidence interval, describes the variability of the point estimate corrected for multiple outcome analyses

Table 2.

Coronary Angiographic and Carotid Artery Intima-Media Thickness Trials of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy

| Trial | Mean Age at Entry, y | Time from Menopause, years1 | Treatment | Mean Duration, years | Outcome | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHIC TRIALS | |||||||

| ERA (16) | 65.8 | 23 | oral CEE 0.625 mg alone or with MPA 2.5 mg | 3.2 | placebo | -0.09±0.02 mm | 0.38 |

| CEE | -0.09±0.02 mm | ||||||

| CEE+MPA | -0.12±0.02 mm | ||||||

| WAVE (17) | 65 | >15 | oral CEE 0.625 mg + MPA 2.5 mg | 2.8 | placebo | -0.010MPA 2.5 mg0.15 mm/y | 0.17 |

| CEE+MPA | -0.048±0.14 mm/y | ||||||

| WELL-HART (18) | 63.5 | 18.2 | oral 17B-E2 1 mg alone or seqiential MPA 5 mg | 3.3 | placebo | 1.89±0.78%S | 0.66 |

| 17B-E2 | 2.18±0.76%S | ||||||

| 17B-E2+MPA | 1.24±0.80%S | ||||||

| CAROTID ARTERY IMT TRIALS | |||||||

| EPAT (19) | 62.2 | 13.4 | oral 17B-E2 1 mg alone | 2.0 | Overall | 0.045 | |

| placebo | 0.0036 mm/yr | ||||||

| 17B-E2 | -0.0017 mm/yr | ||||||

| No lipid-lowering medication | 0.002 | ||||||

| placebo | 0.0134 mm/yr | ||||||

| 17B-E2 | -0.0013 mm/yr | ||||||

| PHOREA (20) | NR | NR | oral 17B-E2 1 mg + gestodene 0.025 mg (hd) or | 48 weeks | placebo | 0.02±0.05 mm* | NS |

| 17B+gest (hd) | 0.03±0.05 mm* | ||||||

| oral 17B-E2 1 mg + gestodene 0.025 mg (ld) | 17B+gest (ld) | 0.03±0.05 mm* | |||||

at randomization

IMT=intima-media thickness

NR=not reported

ERA=Estrogen Replacement Atherosclerosis Trial; WAVE=Women's Angiographic Vitamin and Estrogen Trial; WELL-HART=Women's Estrogen-Progestin Lipid-Lowering Hormone Atherosclerosis Regression Trial; EPAT=Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial;

PHOREA=Postmenopausal Hormone Replacement against Atherosclerosis Trial

CEE=conjugated equine estrogen; MPA=medroxyprogesterone acetate; 17B-E2=17B-estradiol

hd = high dose, gestodene 0.025 mg days 17 to 28 every month

ld = low dose, gestodene 0.025 mg days 17 to 28 every 3 months

mm=millimeter change from baseline in minimum lumen diameter by quantitative coronary angiography (QCA)

mm/y=millimeter per year change in minimum lumen diameter by QCA

%S=percent diameter stenosis change from baseline by QCA

mm/yr=millimeter per year change in common carotid artery intima-media thickness

mm*=change in carotid artery intima-media thickness over 48 weeks

Whereas observational studies have shown a 30-50% reduction in CHD and total mortality in users versus nonusers of HT (1-8), RCTs have shown a null effect on these outcomes when analyzed among all women regardless of age (Table 1). Discordance between observational studies and RCTs is best exemplified within the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) that evaluated HT in both an observational cohort and in RCTs. The WHI observational study of 53,054 women showed a 50% reduction in CHD in women who used estrogen+progestin (E+P) relative to nonusers. In contrast, the risk of CHD was increased 18% in women randomized to daily continuous combined conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg + medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg (CEE+MPA) relative to placebo in the Women's Health Iinitiative estrogen-progestn (WHI-EP) trial (8). The discordance in outcomes between observational studies and RCTs is likely explained by the differences in the characteristics of the cohorts.

Examination of Table 3 clearly shows that the women selected for RCTs were a different population than the women in observational studies. Observational studies reflect the pattern of HT use within the general population. As such, women who used HT in the observational studies were relatively young at the time of HT initiation (30-55 years old), recently postmenopausal (majority initiated HT at the time of menopause), were relatively lean (approximate body mass index of 25 kg/m2) and were predominantly symptomatic mainly with flushing and other menopausal symptoms since these symptoms were the primary reason for using HT. Many of the women in the observational studies who used HT did so for decades (10-40 years). On the other hand, women selected for RCTs were much older with more than 90% of women older than 55 years and on average more than 10 years beyond menopause when randomized (range of trial averages, 13-23 years). Women with significant menopausal symptoms, predominantly flushing, were excluded from RCT participation. Mean duration of therapy (1-6.8 years) in RCTs was also considerably less than that of the HT users in observational studies. Additionally, women in RCTs were on average overweight (approximate body mass index of 29 kg/m2). It is clear that the characteristics of women selected for RCTs were markedly different from those of women studied from the general population in observational studies. This accounts in part for the discordance of the HT effects on CHD from observational studies compared to RCTs when analyzed among all women regardless of age.

Table 3.

Differences in Study Populations between Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies of Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy

| Randomized Controlled Trials | Observational Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age or age range at enrollment (years) | >62 | 30-55 |

| Time since menopause (years) | >10 | >6 (<2)1 |

| Duration of therapy (years) | <7 | >10 |

| Menopausal symptoms (flushing) | excluded | predominant |

| Body mass index (mean) | ~29 kg/m2 | ~25 kg/m2 |

>80% of the women initiated hormone therapy at the time of menopause.

Cardioprotective Effect of HT According to Age and Timing of Initiation

Although the effect of HT on CHD over all ages is null in RCTs, these trials also indicate that there are beneficial effects of HT on CHD according to the timing of initiation of therapy relative to age and menopause (21). This is most evident in WHI, the largest RCT (22). Relative to placebo, women who were randomized to CEE+MPA within 10 years of menopause had a 12% reduction in CHD events whereas women randomized between 10-20 years after menopause had a 23% increased risk of CHD and women randomized more than 20 years after menopause had a 66% increased risk of CHD (p=0.05 for trend)(Table 4)(22). In the WHI-estrogen alone (E) trial, hysterectomized women randomized to daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg (CEE) therapy within 10 years of menopause had a 52% reduction in CHD events, those randomized between 10-20 years after menopause had a 4% reduction in CHD events and those randomized more than 20 years after menopause had a 12% increased risk of CHD, all relative to placebo treated women (Table 4)(22). The p-for-trend was not significant. However, several categories of CHD events (nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary death, confirmed angina and coronary artery revascularization) were significantly reduced 34-45% in the CEE treated group relative to the placebo treated group in women who were 50-59 years old when randomized but not in the women in the 60-69 or 70-79 year old age ranges (15). With the CEE+MPA and CEE trials combined, the trend in CHD reduction according to the time of initiation of HT is stronger than either trial alone, due to the greater sample size. Relative to placebo, women randomized to HT within 10 years of menopause had a 24% reduction in CHD events whereas women randomized between 10-20 years after menopause had a 10% increased risk of CHD and women randomized more than 20 years after menopause had a 28% increased risk of CHD (p=0.02 for trend)(Table 4)(22). Data from observational studies additionally indicate that the beneficial effects of HT on CHD risk depends upon the time from menopause when HT is initiated (23). Although only one-third of the women randomized to the WHI trials were less than 60 years old and less than 5% were within a few years of menopause, the subgroup of women randomized to these trials who are representative of the women in observational studies had reduced CHD with HT. On the other hand, older women (>60 years old) who were randomized to HT many years beyond menopause (>10 years) who are not representative of the women in observational studies had increased risk of CHD with HT.

Table 4.

Relative Risks for CHD: HT Compared to Placebo by Years-Since-Menopause at Randomization into WHI

| Years-Since-Menopause | HR (95% CI) | No. of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| CEE+MPA Trial | ||

| <10 | 0.88 (0.54-1.43) | 5,494 |

| 10-19 | 1.23 (0.85-1.77) | 6,041 |

| ≥20 | 1.66 (1.14-2.41) | 3,653 |

| P-value for trend | 0.05 | |

| CEE Trial | ||

| <10 | 0.48 (0.20-1.17) | 1,643 |

| 10-19 | 0.96 (0.64-1.44) | 2,936 |

| ≥20 | 1.12 (0.86-1.46) | 4,550 |

| P-value for trend | 0.15 | |

| Combined Trials | ||

| <10 | 0.76 (0.50-1.16) | 7,137 |

| 10-19 | 1.10 (0.84-1.45) | 8,977 |

| ≥20 | 1.28 (1.03-1.58) | 8,203 |

| P-value for trend | 0.02 |

HR=Hazard ratio

The beneficial effect of HT on CHD risk according to age or time since menopause has also been demonstrated in a large meta-analysis. Using 23 RCTs (39,049 participants with 191,340 patient-years of follow-up) that reported at least 1 CHD event in postmenopausal women comparing HT with placebo of at least 6 months duration, the effect of HT on CHD events over all ages was null (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.88-1.11)(24). A statistically significant 32% reduction in CHD events was found for subjects less than 60 years old or within 10 years since menopause when randomized (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.96). The magnitude of the reduction in CHD events for the women younger than 60 years old or within 10 years since menopause when randomized was similar to that of observational studies (1-8). On the other hand, the effect of HT on CHD events in women greater than 60 years old or more than 10 years since menopause when randomized was null (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.91-1.16) and similar to that reported over all ages in RCTs (Table 1). The HT-associated RR for CHD events significantly differed between these two groups of women.

Reduction of Total Mortality by HT According to Age of Initiation

Similar to the effect of HT on CHD, WHI indicates that the effect of HT on total mortality is related to the age at which HT is initiated (22). Relative to placebo, women who were 50-59 years old when randomized to CEE+MPA had a 31% reduction in total mortality whereas women 60-69 years old when randomized had a 9% increased risk of total mortality and women 70-79 years old when randomized had a 6% increased risk of total mortality (Table 5)(22). In the WHI-E trial, women who were randomized to CEE therapy between the ages of 50-59 years had a 29% reduction in total mortality, those randomized between the ages of 60-69 years had a 2% increased risk of total mortality and those randomized between the ages of 70-79 years had a 20% increased risk of total mortality, all relative to placebo treated women (Table 5)(22). With the CEE+MPA and CEE trials combined, total mortality was significantly reduced 30% in women 50-59 years old when randomized, whereas women 60-69 years old when randomized had a 5% increased risk of total mortality and women 70-79 years old when randomized had a 14% increased risk of total mortality, all relative to placebo treated women (Table 5)(22). The subgroup of younger women randomized to WHI is more representative of the women in observational studies (Table 3), data from which also indicate that women who use HT relative to those who do not have a reduction in total mortality (1-8,25).

Table 5.

Relative Risks for Total Mortality: HT Compared to Placebo by Age at Randomization into WHI

| Age | HR (95% CI) | No. of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| CEE+MPA Trial | ||

| 50-59 | 0.69 (0.44-1.07) | 5,494 |

| 60-69 | 1.09 (0.83-1.44) | 6,041 |

| 70-79 | 1.06 (0.80-1.41) | 3,653 |

| P-value for trend | 0.19 | |

| CEE Trial | ||

| 50-59 | 0.71 (0.46-1.11) | 1,643 |

| 60-69 | 1.02 (0.80-1.30) | 2,936 |

| 70-79 | 1.20 (0.93-1.55) | 4,550 |

| P-value for trend | 0.18 | |

| Combined Trials | ||

| 50-59 | 0.70 (0.51-0.96) | 7,137 |

| 60-69 | 1.05 (0.87-1.26) | 8,977 |

| 70-79 | 1.14 (0.94-1.37) | 8,203 |

| P-value for trend | 0.06 |

HR=Hazard ratio

The beneficial effect of HT on total mortality according to age has also been demonstrated in a large meta-analysis (26). The effect of HT on total mortality according to age was examined using 30 RCTs (26,708 participants with 119,118 patient-years) that reported at least 1 death in postmenopausal women comparing HT with placebo of at least 6 months duration (26). In this study, the effect of HT on total mortality was null over all ages (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.87-1.18). However, when the data were examined by the age of subjects, a statistically significant reduction in total mortality was found for subjects less than 60 years old at randomization (mean age 54 years). The magnitude of the reduction in total mortality of 39% (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.39-0.95) for the women younger than 60 years old was similar to that of observational studies (1-8,25), notably comparable to that of the Nurses' Health Study, the largest observational study (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.56-0.70)(27). The age at initiation of HT among the women in the observational studies and the age of the younger women randomized to RCT's examined in the meta-analysis is similar. On the other hand, in this meta-analysis, the effect of HT on total mortality in women greater than 60 years old (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.90-1.18) was similar to that reported over all ages in RCTs (Table 1).

In the final analysis, the totality of data from RCTs indicate that young postmenopausal women who initiate HT in close proximity to menopause have reduced total mortality and CHD. These results parallel the consistency of a reduction in total mortality and CHD seen in observational studies where almost all the women initiated HT in close proximity to menopause, typically within 6 years (1-8,25,27).

The Atheroprotective Effect of HT Varies According to Stage of Atherosclerosis

The effect of HT on atherosclerosis progression is determined by the stage of atherosclerosis. This was demonstrated in the sister RCTs, the Women's Estrogen-progestin Lipid Lowering Hormone Atherosclerosis Regression Trial (WELL-HART)(18) and the Estrogen in the Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial (EPAT)(19). WELL-HART and EPAT were designed to determine the effects of HT on the progression of atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women with and without symptomatic pre-existing atherosclerotic vascular disease, respectively. The differing outcomes of no effect of HT on atherosclerosis progression in WELL-HART and a reduction in atherosclerosis progression in EPAT may be related to the timing of the intervention relative to the stage of atherosclerosis as reflected by the arterial imaging methods used in these 2 trials. Quantitative coronary angiography used in WELL-HART is a measure of symptomatic late stage atherosclerosis whereas common carotid artery intima-media thickness (CCA-IMT) used in EPAT is a measure of asymptomatic early subclinical atherosclerosis (28). CCA-IMT was also used in a RCT to evaluate the effects of oral CEE and micronized 17B-estradiol with sequential progestogens on atherosclerosis in 121 perimenopausal women with a mean age of 47 years (29). Although a high drop out rate of 48% prevented reliable conclusions from this RCT, women randomized to HT showed a reduction in the progression of CCA IMT compared with placebo after 2 years of treatment (29). Even though the sample size was limited in this RCT, the magnitude of reduction in CCA IMT progression was similar to that of EPAT (19).

Since age and atherosclerosis are inextricably linked, further investigation will be required to determine which factor is most important in determining whether HT will be atheroprotective or atherogenic. Age and/or time since menopause likely serve as chronological markers for vascular age (stage of atherosclerosis) which is the ultimate determinate as to whether HT will be cardioprotective since human and animal studies indicate that an underlying healthy endothelium is required for HT to be atheroprotective (30).

Duration of HT and Cardioprotection

Evidence for a long-term beneficial effect of HT on CHD is derived from RCTs including HERS and WHI which have the longest randomized follow-up. There was a statistically significant trend toward a reduction in CHD in years 4 and 5 in the CEE+MPA treated group relative to the placebo group (p=0.009 for trend) in HERS (9). In the WHI-EP trial, there was a statistically significant trend toward a reduction in CHD outcome in year 6 and beyond in the HT group relative to the placebo group (p=0.02 for trend)(13).

Further, the beneficial effect on CHD with longer duration of HT use is strongly supported by consistency between the WHI RCTs and the WHI observational study (3,8). Consistent with other observational studies (1,2,4-7), the WHI observational study showed a 50% decreased risk of CHD in E+P users relative to nonusers and a 32% decreased risk of CHD in estrogen alone users relative to nonusers (3,8). In both the WHI-EP trial and the WHI observational study of E+P users (n=17,503 women), the RR for CHD decreased with increasing duration of E+P use (8). After 5 years of E+P use, the risk for CHD in both the WHI-EP trial (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.36-1.21) and the WHI observational study of E+P users (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.67-1.01) was reduced relative to nonusers (Table 6)(8). Reduction of CHD risk with longer duration of HT use is also supported by the consistency between the WHI-E trial and the WHI observational study of estrogen use (3). After 5 years of estrogen alone use, the risk for CHD in both the WHI-E trial (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.57-1.12) and the WHI observational study of estrogen users (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61-0.84) was reduced relative to nonusers (Table 6)(3). The WHI RCTs and observational studies of E+P and estrogen alone demonstrate consistency within the same study across 2 different HTs of a reduction in CHD with duration of HT use as well as consistency with other RCTs and observational studies.

Table 6.

Hazard Ratios for Coronary Heart Disease in the Women's Health Initiative Clinical Trials and Observational Study According to Duration of Use of Estrogen + Progestin and Estrogen Alone*

| Clinical Trial |

Observational Study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of Use (Years) | Hazard Ratio1 | 95% Confidence Interval | Hazard Ratio2 | 95% Confidence Interval |

| CEE+MPA (8) | ||||

| <2 | 1.68 | 1.15-2.45 | 1.12 | 0.46-2.74 |

| 2-5 | 1.25 | 0.87-1.79 | 1.05 | 0.70-1.58 |

| >5 | 0.66 | 0.36-1.21 | 0.83 | 0.67-1.01 |

| CEE alone (3) | ||||

| <2 | 1.07 | 0.68-1.68 | 1.20 | 0.49-2.94 |

| 2-5 | 1.13 | 0.79-1.61 | 1.09 | 0.75-1.60 |

| >5 | 0.80 | 0.57-1.12 | 0.73 | 0.61-0.84 |

Adjusted for age, race, body mass index, educational level, smoking, age at menopause and physical activity.

CEE=conjugated equine estrogen

MPA=medroxyprogesterone acetate

Relative to placebo

Relative to nonusers of hormone therapy

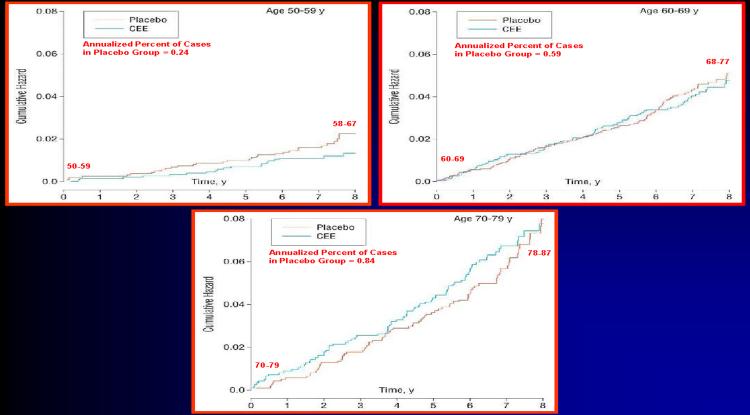

HT has the longest observational follow-up than any other primary prevention therapy for CHD. There is no evidence from observational studies with decades of follow-up that HT causes an increased risk of CHD with long-term use. In fact, observational studies have demonstrated a long-term benefit of HT on total mortality and CHD for up to 10-40 years of HT use. In addition, HT has some of the longest RCT data, up to 8 years of randomized treatment. Over this period of time, there is no evidence that CHD risk increases with longer duration of CEE therapy (Figure 1)(15). In fact, as shown by the cumulative hazard in WHI-E, women between 50-59 years old when randomized to CEE therapy had a reduction in CHD events relative to placebo over 8 years of HT at which time women were 58-67 years old (Figure 1). The cumulative hazard indicated that women between 60-69 years old when randomized to CEE therapy or placebo had the same rates of CHD. After 8 years of treatment, when women were 68-77 years old, there was no evidence that the women receiving HT had any greater risk of CHD relative to placebo (Figure 1). In fact, after 6 years of therapy, the CEE curve dipped below the placebo curve (Figure 1). Women at the greatest risk of CHD, those who were between 70-79 years old when randomized showed a greater risk for CHD when receiving HT relative to placebo. However, after 8 years of treatment when women were 78-87 years old, there was no evidence that the women receiving HT had any greater risk of CHD relative to placebo. In fact, the HT and placebo event curves came together after 8 years of treatment (Figure 1). WHI indicates that even amongst the women at greatest risk for CHD, long-term HT does not increase CHD events above that of placebo treated women (15).

Figure 1.

Annualized Percentage of Coronary Heart Disease Events in the Women's Health Initiative Estrogen Trial by Age at Baseline

Reduction of CHD risk with prolonged HT use (more than 6 years) is consistent across the large RCTs (HERS and WHI-EP), observational studies, case-control studies and arterial imaging studies (3,8,9,13,25,31-35). Comparison of the results from RCTs (HERS and WHI-EP), prospective observational studies and case-control studies indicates that confounding and selection biases do not explain the consistent evidence that HT is associated with a duration-dependent lowering of CHD risk. The WHI trials along with observational studies suggest that this duration-dependent lowering of CHD risk may predominantly manifest in women initiating HT in close proximity to menopause (within 6 years) or before 60 years of age.

Risks of HT in Recently Menopausal Women

Although many of the adverse effects of HT were known prior to conduct of the RCTs of CHD prevention, the magnitude of these effects were not completely understood. WHI and other RCTs have indicated that the majority of adverse outcomes associated with HT are rare (<1 event/1,000 treated women) (36). In addition, WHI has demonstrated that recently menopausal and younger postmenopausal women have lower absolute risks for adverse outcomes from HT than do remotely menopausal and older postmenopausal women (22). For example, the time- and age-related stroke data from WHI indicate that the number of additional cases of stroke is rare for CEE+MPA therapy when initiated in women less than 5 years since menopause (3 extra strokes per 10,000 women per year of CEE+MPA therapy) and even reduced for CEE therapy in women less than 60 years old (2 fewer strokes per 10,000 women per year of CEE therapy)(36). Even though there is a rare incidence of stroke with CEE+MPA therapy, this magnitude of risk occurs with other commonly used medications such as raloxifene (36).

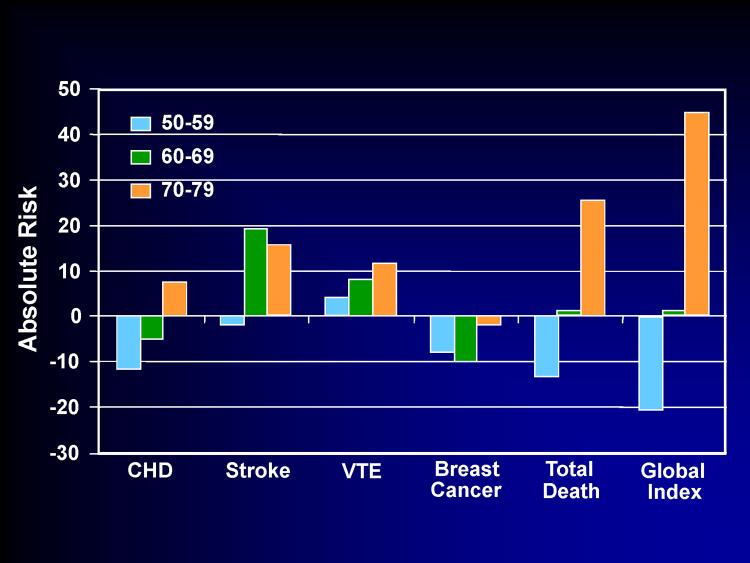

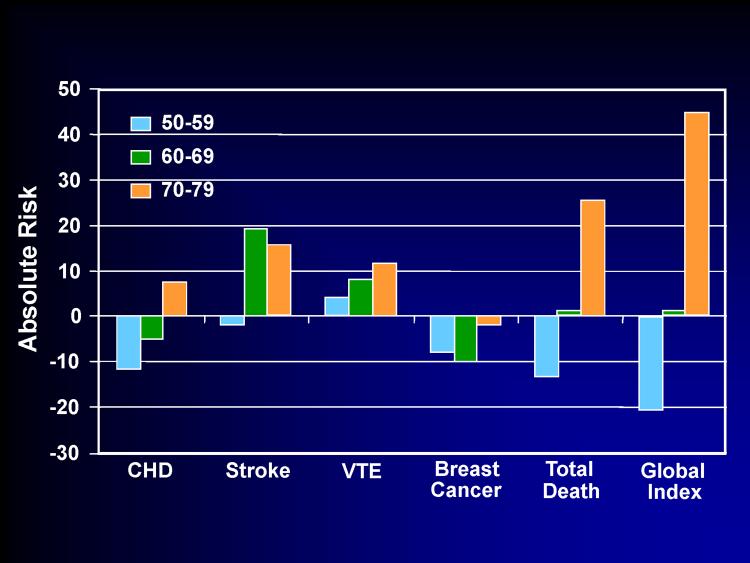

For women randomized between 50-59 years old in the WHI-E trial, the additional risks from CEE therapy were negligible. The greatest additional risk in this age group was for venous thromboembolic events, which was also rare (4 events per 10,000 women per year of CEE therapy) and comparable to many other commonly used medications such as fenofibrate (36). Relative to placebo, CEE alone was associated with less breast cancer across all age ranges. The mortality rate in younger women was reduced with CEE therapy. Event outcomes by age are shown for CEE therapy compared to placebo from the WHI-E trial (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of Events per 10,000 Women per Year of Conjugated Equine Estrogen Therapy Compared to Placebo in the Women's Health Initiative Estrogen Trial by Age at Baseline

Clinical Perspective of HT Relative to other Primary Preventive Therapies for Women

Lipid-lowering medications, predominantly HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are the mainstay for the primary prevention of CHD in women (37,38). The cumulated data across 6 RCTs and 11,435 women however, do not provide convincing evidence for the reduction of CHD or total mortality with lipid-lowering therapy in the primary prevention of CHD in women (39): RR, 0.89 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.69-1.09) for CHD events; RR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.22-1.68) for nonfatal myocardial infarction; RR, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.62-1.46) for total mortality; and, RR, 1.07 (95% CI, 0.47-2.40) for CHD mortality. Data supporting lipid-lowering therapy for the primary prevention of CHD in women and upon which current recommendations are based are small compared with those of men (39). Recommendations for lipid-lowering therapy in the primary prevention of CHD in women are predominantly extrapolated from data derived from men and from secondary prevention trials in women (37,38).

Additionally, prophylactic use of aspirin for the primary prevention of CHD in women is a common medical practice recommended by major health organizations (38). However, the Women's Health Study (WHS) of 39,876 healthy women randomized to aspirin 100 mg every other day or placebo for 10 years showed a null effect of aspirin on the primary trial end point of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke or cardiovascular death (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.80-1.03) (40). Total mortality and cardiovascular death from any cause were also unaffected by aspirin. Within this null finding was no effect on fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.84-1.25) and a 17% (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.69-0.99) reduction in stroke with aspirin relative to placebo; 2 fewer strokes per 10,000 women per year of aspirin use. Although ischemic stroke was reduced 24% (RR, 0.76, 95% CI, 0.63-0.93) with aspirin relative to placebo, hemorrhagic stroke was also increased 24% (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.82-1.87) with aspirin relative to placebo.

In stark contrast to lipid-lowering and aspirin therapy for the primary prevention of CHD, the cumulated data across more than 2 dozen RCTs demonstrate a significant reduction in total mortality and CHD in women less than 60 years old or less than 10 years since menopause when randomized to HT relative to placebo (Table 7) (24,25).

Table 7.

Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease with Hormone Therapy in Clinical Perspective

| Hormone Therapy1(24,26) | Lipid Lowering (39) | Aspirin Therapy (40) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD | 0.68 (0.48-0.96) | 0.89 (0.69-1.09) | 0.91 (0.80-1.03) | ||

| Total Mortality | 0.61 (0.39-0.95) | 0.95 (0.62-1.46) | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | ||

| No. of Patients (Annualized %) |

No. Additional Breast Cancer Cases per 10,000 Women per Year | ||||

| Study | Placebo | Statin | Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Statins meta (41) | 64 (0.23) | 81 (0.30) | 1.33 | (0.79-2.26) | 7 |

| Statins meta (42) | 124 (0.29) | 132 (0.31) | 1.04 | (0.81-1.33) | 2 |

| WHI-EP (44) | 150 (0.33) | 199 (0.42) | 1.24 | (adj 0.97-1.59) | 9 |

| WHI-E (43)2,3 | 161 (0.42) | 129 (0.34) | 0.82 | (0.65-1.04) | -8 |

In women <60 years old and/or <10 years-since-menopause when randomized

Adherence adjusted = 0.67 (0.47-0.97)

Ductal carcinoma = 0.71 (0.52-0.99)

On the other hand, the type and magnitude of risks associated with statin and aspirin therapy for the primary prevention of CHD are similar to those of HT. In one meta-analysis reporting data from 5 randomized controlled trials of statin therapy, a 33% (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.79-2.26) increased risk of breast cancer associated with statin use was reported (41). There were 81 cases of breast cancer per 27,112 women-years in those women randomized to statin therapy and 64 cases of breast cancer per 27,462 women-years in those women randomized to placebo indicating 7 additional breast cancer cases per 10,000 women per year who used statin therapy (41). In a second meta-analysis reporting data from 7 randomized controlled trials, a 4% (RR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.81-1.33) increased risk of breast cancer associated with statin use was reported (42). There were 132 cases of breast cancer per 42,412 women-years in those women randomized to statin therapy and 124 cases of breast cancer per 42,757 women-years in those women randomized to placebo indicating 2 additional breast cancer cases per 10,000 women per year who used statin therapy (Table 7)(42).

Although the breast cancer results from WHI differ with CEE alone associated with a reduction in breast cancer risk (43) and CEE+MPA associated with an increased risk (44), the magnitude of risk seen with statin therapy is comparable to that of CEE+MPA therapy (36). In the WHI-EP trial, the RR for breast cancer was increased 24% with CEE+MPA therapy resulting in 9 additional cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women per year of CEE+MPA therapy (Table 7)(44). Total mortality and mortality due to breast cancer did not differ between CEE+MPA therapy and placebo. A more detailed analysis from WHI-EP with adjustment for breast cancer risk factors indicated a 20% (RR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.94-1.53) increased risk of breast cancer associated with CEE+MPA therapy (45). The elevated breast cancer risk in WHI-EP was limited to those women who used postmenopausal HT prior to the WHI-EP trial (45). In HERS, CEE+MPA therapy (same HT as WHI-EP) was associated with a non-significant increased risk of breast cancer of 12 additional cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women per year of CEE+MPA therapy (9). The increased absolute risk of breast cancer with statin therapy contrasts with CEE therapy. In the WHI-E trial, breast cancer was decreased with CEE therapy relative to placebo 18% (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.65-1.04) resulting in 8 fewer cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women per year of CEE therapy (Table 7) (43). In subgroup analyses, breast cancer risk was further reduced in those women adherent to CEE therapy relative to placebo (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47-0.97) and in those women who developed the most common form of breast cancer, ductal carcinoma (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52-0.99)(43). In the final analysis, the cumulated data indicate that the absolute risk of breast cancer associated with statin therapy and oral daily continuous combined CEE+MPA therapy as seen in WHI-EP and HERS is rare and similar; -1 to 7.7 additional breast cancers per 1,000 women per year of statin therapy versus -0.8 to 1.2 additional breast cancers per 1,000 women per year of HT (36). Although these trials show that the risk of breast cancer ascertained over the duration of the trial associated with CEE+MPA therapy is rare and at most of borderline significance, the same magnitude of risk exists with statin therapy. Such comparisons bring into focus the clinical perspective of the breast cancer risk of oral daily CEE+MPA therapy relative to other commonly used medications for preventive therapies in women (Table 7).

In the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly Risk (PROSPER), a 3.2 year RCT in men and women 70 to 82 years old, the diagnosis of new cancer was significantly increased 25% (hazard ratio (HR), 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.51) in the pravastatin treated group relative to placebo accounting for approximately 52 additional cancer cases per 10,000 persons per year of pravastatin use (46). On the other hand, the effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in 3,000 women was null (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.79-1.18). Unlike WHI-EP, gastrointestinal cancer risk was increased by 46% with pravastatin treatment relative to placebo in PROSPER (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.00-2.13); 22 additional cases of gastrointestinal cancer per 10,000 persons per year of pravastatin use (46). In WHI-EP, colorectal cancer was reduced with CEE+MPA therapy relative to placebo 37% (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43-0.92) resulting in 6 fewer cases of colorectal cancer per 10,000 women per year of CEE+MPA therapy (12).

Although lipid-lowering trials other than PROSPER have not shown statistically significant increased risk for cancer overall, the absolute cancer risk in the primary prevention trials with statins that have reported cancer incidence is consistently elevated relative to placebo-treated subjects (47,48). The overall absolute cancer risk specifically determined in women in the primary prevention trial Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) was elevated with approximately 15 additional cases of cancer per 10,000 women per year of lovastatin use (47). In the primary prevention trial Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT), the overall absolute cancer risk was 5 additional incident cases of cancer and 7 additional cancer deaths per 10,000 persons per year of pravastatin use compared to placebo (48). Site-specific cancers have not been reported in all lipid-lowering RCTs and thus the breast cancer-related risk in particular remains unknown across all lipid-lowering medications (36).

Bleeding diatheses, not seen with HT were all significantly increased with aspirin versus placebo in the WHS (40). Relative to placebo, any gastrointestinal bleeding was increased 22% (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.10-1.34) and gastrointestinal bleeding requiring blood transfusion was increased 40% (RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.07-1.83) with aspirin. The absolute increased risk for any gastrointestinal bleeding was 8 additional cases per 10,000 women per year of aspirin use. The other RCTs of aspirin therapy that included women, the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) (n=8883 women, 3.8 years) (49) and the Primary Prevention Project (PPP) (n=2583 women, 3.6 years) (40,50) were of smaller size and shorter duration than WHS but showed similar magnitudes of bleeding risk with no overall reduction in cardiovascular events. Meta-analyses confirm the same or greater levels of risks for bleeding diatheses and hemorrhagic stroke for men where the data are more substantial since the majority of study participants in the RCTs of aspirin have been men (51). Sudden death was increased in men randomized to aspirin versus placebo. In the Physicians' Health Study (PHS) (n=22,071), there were 22 sudden deaths in the men randomized to aspirin and 12 such events in men randomized to placebo (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 0.91-4.23) or an increased absolute risk of 5 sudden deaths per 10,000 men per year of aspirin use (52). Whether aspirin causes sudden death in women is unknown since these data have not been reported in WHS, HOT or PPP. The magnitude of the side effects from bleeding associated with aspirin resembles those of CEE+MPA therapy (12).

In contrast to lipid-lowering and aspirin therapy for the primary prevention of CHD, the cumulated data indicate that in postmenopausal women less than 60 years old or within 10 years of menopause, HT reduces total mortality and CHD. Initiation of HT in close rather than remote proximity of menopause appears to be key in the full expression of the cardioprotective effects of HT (24,26,30,36). On the other hand, in specific trials, certain risks of lipid-lowering medications such as breast cancer resemble those of CEE+MPA reported from WHI-EP (Table 7)(36).

Conclusion

The totality of data indicate that the effect of postmenopausal HT on total mortality and CHD is modified by the timing of initiation (age and time since menopause) and the duration of therapy (>6 years of use). The absolute risks associated with HT are rare (less than 1 additional event per 1,000 women) and even rarer in women who initiate HT below age 60 years or within 5 years of menopause. It is this latter group of women who are in the most need of symptomatic relief of menopausal symptoms such as flushing for which estrogen remains the most effective therapy (53). The risks associated with estrogen alone appear to be quite negligible. RCTs are supported by approximately 40 observational studies that also indicate that initiation of HT early in the postmenopausal period and continued for a prolonged period of time results in a significant reduction of total mortality and CHD. Comparison of the results from RCTs, observational studies and case-control studies indicates that selection bias does not explain the consistent evidence that HT is associated with a duration- and time-dependent lowering of total mortality and CHD. The window of opportunity for maximal expression of the beneficial effects of HT on CHD appears to be initiation of HT within 6 years of menopause and/or by 60 years of age and continued for 6 years or more.

As with all medications, especially those used for primary prevention of disease, benefits must be carefully weighed against risks. RCTs of HT have confirmed that the risks of HT are rare and of the same magnitude as other primary prevention therapies for CHD (36). Further analyses of the subgroups of women within RCTs that resemble the women from observational studies indicate a consistency between the 2 types of study designs with similar benefit of HT on the reduction of total mortality and CHD. Unlike lipid-lowering and aspirin therapy, HT reduces CHD and more importantly, total mortality in this sub-group of women.

No other single preventive therapy offers systemic-wide effects for women and as such, the use of HT in the primary prevention of disease must be considered differently than medications currently used for prevention. Administration of exogenous estrogen after menopause should not be viewed as a therapy for any specific disease entity but as a replacement for a hormone that appears by the cumulated data to lessen the impact of aging on a multitude of organ systems such as the cardiovascular, skeletal and potentially the central nervous systems (30). Timing in the initiation of hormone replacement before tissue damage due to aging becomes too extensive appears to be the key for successful prevention and amelioration of any further damage (30).

In the final analysis, the discordance in total mortality and CHD outcomes between RCTs and observational studies is a function of the differences in study design and the characteristics of the populations studied and not the result of one study design being superior to another. In fact, as data from RCTs accumulate, it is important to realize how much the results look more and more like the more than 40 consistent observational studies that indicate that young postmenopausal women with menopausal symptoms who use HT for long periods of time have lower rates of total mortality and CHD than comparable postmenopausal women who do not use HT.

References

- 1.Grodstein F, Stampfer M. The epidemiology of coronary heart disease and estrogen replacement in postmenopausal women. Prog Cardiol Dis. 1995;38:199–210. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(95)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grodstein F, Stampfer M. Estrogen for women at varying risk of coronary disease. Maturitas. 1998;30:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prentice RL, Langer R, Stefanick ML, et al. Combined analysis of Women's Health Initiative observational and clinical trial data on postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:589–599. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson SG, Meade TW, Greenberg G. The use of hormonal replacement therapy and the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction in women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1989;43:173–178. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falkeborn M, Persson I, Adami HO, et al. The risk of acute myocardial infarction after oestrogen and oestrogen-progestogen replacement. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:821–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Atkins D, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction associated with the combined use of estrogens and progestins in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1333–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen and progestin use and the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:453–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prentice RL, Langer R, Stefanick ML, et al. Combined postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease: toward resolving the discrepancy between observational studies and the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:404–414. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke SC, Kelleher J, Lloyd-Jones H, et al. A study of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with ischemic heart disease: the Papworth HRT Atherosclerosis Study. BJOG. 2002;109:1056–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry N, Gilmour K, Hannaford P, et al. Oestrogen therapy for the prevention of reinfarction in postmenopausal women: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:2001–2008. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)12001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy menopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:523–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Women's Health Initiative Steering Committee Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsia J, Langer RD, Manson JE, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease: the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:357–365. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan KB, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:522–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters DD, Alderman EL, Hsia J, et al. Effects of hormone replacement therapy and antioxidant vitamin supplements on coronary atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:2432–2440. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Azen SP, et al. Hormone therapy and the progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:535–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, et al. Estrogen in the prevention of atherosclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:939–953. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angerer P, Stork S, Kothny W, et al. Effect of oral postmenopausal hormone replacement on progression of atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:262–268. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo R. What is the cardioprotective role of hormone replacement therapy? Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2003;5:56–66. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JA, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;297:1465–1477. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grodstein F, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ. Hormone therapy and coronary heart disease: the role of time since menopause and age at hormone initiation. J Women's Health. 2006;15:35–44. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Greyber E, et al. Coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson BD, Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK. Decreased mortality in users of estrogen replacement therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Greyber E, et al. Mortality associated with hormone replacement therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grodstein F, Manson JE, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective, observational study of postmenopausal hormone therapy and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:933–941. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-12-200012190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blankenhorn DH, Hodis HN. Duff Memorial Lecture: arterial imaging and atherosclerosis reversal. Arterioscl Thromb. 1994;14:177–192. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Kleijn MJJ, Bots ML, Bak AAA, et al. Hormone replacement therapy in perimenopausal women and 2-year change of carotid intima-media thickness. Maturitas. 1999;32:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Randomized controlled trials and the effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular disease: facts, hypotheses and clinical perspective. In: Lobo RA, editor. Treatment of the postmenopausal woman. 3rd ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 529–564. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chilvers CED, Knibb RC, Armstrong SJ, et al. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a case control study of women in the East Midlands, UK. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:2197–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heckbert SR, Weiss NS, Koepsell TD, et al. Duration of estrogen replacement therapy in relation to the risk of incident myocardial infarction in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1330–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrara A, Quesenberry CP, Karter AJ, et al. Current use of unopposed estrogen and estrogen plus progestin and the risk of acute myocardial infarction among women with diabetes: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente diabetes registry, 1995-1998. Circulation. 2003;107:43–48. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042701.17528.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akhrass F, Evans AT, Wang Y, et al. Hormone replacement therapy is associated with less coronary atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5611–5614. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett-Connor E, Laughlin GA. Hormone therapy and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic postmenopausal women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Menopause. 2005;12:40–48. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200512010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Postmenopausal hormone therapy in clinical perspective. Menopause. 2007;14:944–957. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31802e8508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672–693. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh JME, Pignone M. Drug treatment of hyperlipidemia in women. JAMA. 2004;291:2243–2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, et al. Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsavaris N, et al. Use of statins and breast cancer: a meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials and nine observational studies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8606–8612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295:1647–1657. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3243–3253. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Rossouw JE, et al. Prior hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin. Maturitas. 2006;55:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clearfield M, Downs JR, Weis S, et al. Air force/Texas coronary atherosclerosis prevention study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS): efficacy and tolerability of long-term treatment with lovastatin in women. J Women's Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:971–981. doi: 10.1089/152460901317193549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT-LLT) JAMA. 2002;288:2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kjeldsen SE, Kolloch RE, Leonetti G, et al. Influence of gender and age on preventing cardiovascular disease by antihypertensive treatment and acetylsalicylic acid: the HOT study. J Hypertens. 2000;18:629–642. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collaborative group of the Primary Prevention Project (PPP) Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomized trial in general practice. Lancet. 2001;357:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03539-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:161–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steering Committee of the Physicians' Health Study Research Group Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians' Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1984;321:129–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhumoral therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:2057–2071. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]