Abstract

Whether competition among large groups played an important role in human social evolution is dependent on how variation, whether cultural or genetic, is maintained between groups. Comparisons between genetic and cultural differentiation between neighboring groups show how natural selection on large groups is more plausible on cultural rather than genetic variation.

Keywords: altruism, cultural FST, group selection, prosociality

Human societies are unusual among vertebrates. While people in small-scale societies exhibit much more cooperation and division of labor than other primates, people in even very large societies also show strong tendencies toward altruism. Warfare, food sharing, and taxation are all examples of prosocial patterns of behavior that are common in human societies but nearly completely absent in other vertebrates. Even when plausible analogues can be found in other vertebrates, the scale of costliness of human altruism is extraordinary (1).

Explaining the levels of human altruism observed ethnographically and experimentally has proven to be difficult. Much of this altruism is directed at strangers, and so is difficult to explain as simple reciprocity, or it benefits entire tribes or nations of only distant genealogical kin, and so is difficult to explain as altruism among individuals sharing recent common ancestry. Another scenario many researchers, since at least Darwin (2), are concerned with is competition among residential human groups that are too large to comprise close genealogical kin (2–6). If groups differ in the frequency of individuals who are willing to sacrifice their own labor, time, or safety in ways that promote the competitive ability of the residential group, then over time groups with higher frequencies of such “altruists” may tend to replace groups with fewer (7–9).

In this paper, we refer to this scenario as “group-level selection,” the evolution of behavior that reduces individual fitness but increases the average fitness within large groups of only distantly related individuals. By “distantly related,” we mean that most individuals within the residential group do not share very recent common ancestors, and so common descent alone does not maintain much genetic variation among residential groups. Nevertheless, given the right population structure and low rates of mixing among groups, individuals within groups may be much more genetically similar to one another than they are to members of other groups, and therefore they may be closely “related” in one important sense of the term (10). If genetic variation among groups is sufficiently large, evolutionary theory predicts that self-sacrifice on behalf of large residential groups can evolve under the same processes that evolve self-sacrifice on behalf of close kin. This is because all hypotheses about the evolution of altruistic behavior—behavior that reduces the absolute fitness of the actor but increases the absolute fitness of recipients—hinge on processes that change and maintain variation among social groups (11–14).

Selection for altruism in such large groups, however, remains a controversial topic in part because it is not clear that enough between-group variation existed in human societies to make it an appreciable evolutionary force (15). In very large residential groups, migration can quickly erode between-group genetic variation. Nevertheless, recent work argues that sufficient variation did exist by invoking reproductive leveling (7) [see also (16)]. Reproductive leveling reduces the amount of between group variation needed for selection to favor group-beneficial but individually-costly traits. While it is not known how the estimates of genetic differentiation for small forager groups reported in (7) relate to Pleistocene foraging groups (see SI), it is intriguing to note that reproductive leveling itself already has strong hints of prosociality, begging the question of how it could evolve before altruism (17). This illustrates that for genetic selection to favor altruism in large residential groups, theorists need to invoke particularly strong assumptions.

An alternative scenario is that human propensities to cooperate arose through selection on cultural rather than genetic variation (15, 18). Humans developed the capacity for complex culture perhaps beginning 250,000 years ago (19). Since that time, culturally transmitted traits have come, along side of genes, to have a large influence on human behavior. Ever since the advanced human capacity for social learning began, groups of individuals likely began rapid divergence in behavior due to cumulative cultural changes. This behavioral variation between groups can persist, given the right kinds of cultural evolutionary forces (20). Even among our closest living relatives, chimpanzees, plausibly socially-learned traits show some between group variation (21).

Selection for culturally-prescribed altruists occurs through the same process as for genes: groups of altruists leave more daughter societies (8, 9). However, one advantage that cultural variation has over genetic is that it does not require violent inter-group competition, nor group extinctions (22, 23). If failed groups were incorporated routinely into successful ones, conformist transmission and other forms of resocialization of failed groups can lead to effective cultural selection on groups even though such a pattern will generate rates of migration that keep genetic FST very low between neighbors. Thus selection on culture can be powerful precisely when genetic selection at the group level is weakest.

What is the scope for group-level selection on cultural variation and how does this compare to the equivalent for genes? A number of mechanisms may permit cultural variation to be larger than genetic variation between groups (15, 20). If these mechanisms are important, the scope for group-level selection on culture will be much greater than for genes. Here we compute estimates of cultural variation among human groups and compare these to previous estimates of genetic variation among groups. We restrict ourselves to neighboring groups in the main analysis since only neighbors could compete directly. Despite good reasons to believe our estimates of cultural variation are underestimates, we find much greater scope for multilevel selection on human culture than on human genes. These results call for attempts to produce better estimates relevant to quantitative models of human cultural evolution.

Calculating Cultural and Genetic Variation.

The formal condition for altruism to arise can be expressed using the Price equation (11, 13). Unlike most evolutionary theory, the Price equation is axiomatic—it does not depend upon simplifying assumptions, but rather is an exact description of how selection works. Put in terms of regression coefficients and the statistic FST, a measure of genetic differentiation between populations (24), the condition for the frequency of altruism to increase is:

Here β(wg, pg) is the increase in the mean fitness of the group with an increase the frequency of altruists, and β(wig, pig) is the fitness decrease of the individual acquiring the altruistic allele. FST estimates the proportion of the total variation in a trait or set of traits (or alleles) that is accounted for by between-group differences. The greater the genetic differentiation (FST) between two groups, the greater the scope for selection at the group level. View the left hand side of the inequality as the benefit-cost ratio for the addition of another altruist in a population at the scale of the group and individual, respectively. The right-hand side of this inequality should be computed for two populations that may compete. There is no reason, in principle, not to use the same F-statistic, FST, for use in describing cultural differentiation between populations, because the derivation of the Price equation makes no assumptions about the nature of the underlying variants. As in the case of genetic FST, cultural FST is the proportion of the total variance in allele (or trait) frequencies found between groups. The higher this number, the greater the cultural differentiation is between groups. By comparing FST for genes and culture, we can assess the relative ability of either inheritance system to respond to group-level selection.

An obstacle to computing cultural FST is that social anthropologists have not traditionally sampled individuals explicitly. The one exception known to us is analyzed in the SI and Table S2. Instead, most ethnography consists of statements about normative behavior that is often observed to vary among groups. To compute cultural FST, we require systematic samples of individual beliefs or behavior.

We used the World Values Survey (WVS) (25) as a source of data to compute cultural FST for a fairly large sample of national neighbors. The WVS asks a large battery of questions that are likely to be heavily influenced by culture in a large number of countries. The sample size within countries is also large and thus favorable to calculating precise estimates of within and between group variation. We then compare these corresponding genetic FST estimates from (24).

Results

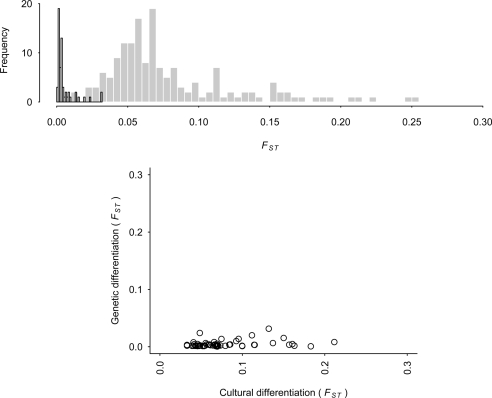

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the distribution of FST estimates for culture and genes and the bottom panel shows how these estimates relate to equation (1) and the scope for selection among groups. It is evident that the scope for group-level selection, as described in equation (1), is much greater for culture than genes. Cultural FST (mean = 0.0800, median = 0.0660) between populations is more than order of magnitude larger than their corresponding genetic FST (mean = 0.0053, median = 0.0032). In Table S1 in the SI, we list all of the pairwise cultural FST values. The full tables for genetic FST are given in (24). In the case of both culture and genes, the similarity of neighbors is much greater than non-neighbors.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of genetic and cultural differentiation. Above: Histogram of 150 cultural FST (gray fill) and 59 genetic FST (black border) for neighboring countries calculated from the World Values Survey and in (24), respectively. Bottom: Plot of the cultural against genetic FST for 59 pairs of neighboring countries.

From these estimates we can compute the minimum group benefit over individual cost ratio that would favor altruism, the left-hand side of equation (1). For genes the mean and median benefit across all paired countries is 437 and 311 (range from 31–2,272), while the respective mean and median for cultural traits is 16 and 14 (range 3–75). For genes, group beneficial behaviors should be hundreds of times greater than the individual cost to be favored by selection, whereas for culture, group-level selection can operate under much less stringent conditions.

Discussion

Our calculations show much greater scope for cultural rather than genetic group-level selection, although we should acknowledge how this inference may be limited. The low and very low genetic FST values that characterize modern national neighbors might not be typical of ancestral Pleistocene populations. Certainly, much smaller population sizes would have generated more drift. On the other hand, we do not think that the available data from living populations is consistent with neighbors having FST values as high as 0.076, the baseline figure used in (7) (see SI). It is difficult to know how last Glacial population structures might have been like compared to Holocene hunter-gatherers. Human populations densities in most times and places in the Pleistocene were apparently very low. Highly variable climates and a disproportionate emphasis on big game hunting in the last glacial compared to the Holocene would probably have made populations more mobile and more prone to long distance movements in the last glacial. Even in Upper Paleolithic Western Eurasia last glacial populations were apparently only on the order of tens of thousands of people and division into markedly distinct ethnic groups was absent (26). The main Western Eurasian Upper Paleolithic cultures, the Aurignacian and Gravettian, occurred over the whole of Europe and neighboring West Asia without any strongly marked stylistically marked subdivision (27). The culturally innovative Southern African Still Bay and Howieson's Poort Middle Stone Age traditions appear to have been widespread spatially like the Upper Paleolithic but were more restricted in time than the Aurignacian and Gravettian (28). In most parts of the Old World for most of the history of Anatomically Modern Humans most populations made rather simple Middle Stone Age or Mode 3 tools (28). Population densities of Mode 3 toolmakers were probably even lower than Upper Paleolithic West Eurasians (29).

We are frustrated to have to use estimates of FST derived from late Holocene populations to infer what transpired in Middle and Late Paleolithic contexts. The paleoclimatology and paleoanthropology suggest that Paleolithic populations were structured much differently than contemporary populations, even than the ethnographic and genetic samples we have from small-scale foraging populations. Nevertheless, the same differences in evolutionary processes that allow culture more easily than genes to maintain between-group differences should have operated in the Middle and Upper Paleolithic as well as in contemporary populations. The large differences we find between cultural and genetic FST argue that that the evolutionary processes acting on these two systems of inheritance would have to be very different in the late Pleistocene to affect the qualitative conclusion that the scope for cultural group-level selection was greater than for genetic group-level selection, then as now.

The WVS is not the best dataset to use for this purpose. Ideally, we would like to have neighbor cultural FST estimates for small-scale societies as close as possible in structure to those that characterized our Pleistocene ancestors. One set of data from Africa does provide data sufficient to compute cultural FST (see SI and Table S2), but no genetic data are available for these groups (30). Cultural FST estimates reported here are likely the lower bound for ethnic groups as questionnaires typically underestimate behavioral variation across groups (31, 32). Also, most nations have multiple ethnic groups that live within their boundaries and different nations often have the same or similar subcultures as neighboring nations. Some of the variation in the WVS questions may be genetic, as behavior geneticists often report appreciable (genetic) heritabilities for seemingly cultural traits like political preferences (33). As we see above, genetic FST is generally much smaller than cultural FST so a mixture of genetic and cultural effects will lead to an underestimate of cultural FST. The discussions by anthropologists of differences between tribal scale societies that presumably most resemble the late Pleistocene conditions under which our propensities for cooperation arose suggest that cultural differences between tribes were roughly similar to those obtaining between ethnic groups in modern societies [e.g., (34)]. For example, different tribes often have different languages or dialects that may function to limit communication between them (35). As with modern societies, immigration into simple societies was often accompanied by cultural assimilation [e.g., (36)]. Thus, national scale data offer some interesting insights on neighbor cultural and genetic differences.

Finding that there is greater scope for inter-group competition to select for prosociality on culture rather than genes does not mean that genes are unimportant to the story. With our early ancestors inheriting both cultural and genetic variants, one inheritance system likely exerted pressure on the other. Support for gene-culture coevolution for well-studied physiological traits can be logically extended to the puzzle of human prosociality. Cattle domestication and the innovation of dairy farming led to selection pressure on genes to produce the enzymes to break down milk sugars beyond weaning (37). Similarly, innate propensities to cooperate might have evolved by gene-culture coevolution rather than by selection among groups for solely genetic variants (38). That is, the evolution of cultural rules mandating cooperation between group members could exert ordinary selection pressures for genotypes that obey cultural rules. Social selection mechanisms such as exclusion from the marriage market, denial of the fruits of cooperative activities, banishment, and execution would have exerted strong selection against genes tending toward antisocial behavior. Social selection in favor of genes that predisposed individuals toward prosociality are also easy to imagine.

One important function of our calculation is to call attention to the importance and feasibility of quantitatively estimating the important parameters of evolutionary models in human populations. Data from small-scale human societies that better resemble the kinds of social systems important in our evolutionary past would be particularly interesting. (See SI for an analysis of four east-African populations). A conjecture based on ethnographic accounts [e.g., (39)] is that cultural selection among groups is often driven by differences in institutions. One well-described case, the Nuer versus Dinka tribes, exemplifies contest-based selection acting on institutional cultural variation among groups. Differences in marriage institutions led to a deeper reckoning of kinship among the Nuer compared to the Dinka, which led to the Nuer raising larger fighting forces and the expansion of the Nuer at the expense of the Dinka. These fights were not genocidal and many defeated Dinka families were incorporated into Nuer tribes, complete with fictive descent to give them a place in the Nuer social order (36). In any case, the Nuer and Dinka peoples were genetically similar, as neighbors would typically have been before long distance mass transport was available. The way the losing side was integrated demographically, and re-socialized culturally, into Nuer society further reduced the possibility of maintaining genetic variation between the groups. Thus the genetic variation between groups in such contexts may be quite small, while cultural variation can remain quite large.

The Nuer-Dinka case illustrates this feature of human inter-group competition. The Nuer-Dinka difference was institutional. Human social life is typically regulated by rules of conduct that take the form of self-reinforcing games (40). Few people will behave contrary to the institution and the non-conformists that do exist will not usually be adhering to the institutions of a neighboring group. Thus selection acts on competing equilibria as far as the traits upon which group-level selection is acting. The situation is as if cultural FST was approximately 1 as far as the relevant trait is concerned, as if each population was nearly monomorphic for the same haploid allele.

We conclude that the available evidence suggests that direct group-level selection on genes played a smaller role in human evolution than group-level selection on cultural variation. Human genes affecting social behavior, such as our docility compared to chimpanzees (41), probably arose by gene-culture coevolution (42).

Materials and Methods

Using data from four phases of the WVS, we computed a pair-wise cultural FST for 154 neighboring pairs of countries sampled therein. We restrict ourselves to neighboring countries in the main analysis since only neighbors could compete directly. We matched these estimates to available estimates of genetic FST from a database of calculated genetic differentiation between nations and ethnic groups (24).

For discrete traits, questions in the World Values Survey (WVS) were regarded as “loci” and responses as “alleles.” In the WVS, data such as “no answer” or “not asked” and the like were not included in the calculation because they were not considered responses. Questions that explored personal idiosyncrasies rather than cultural beliefs were omitted (e.g., self-reported state of health). Further, similar responses were pooled as one response if the choice of responses could not be considered as cardinal. For example, if the possible responses were “agree,” “strongly agree,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree,” then the first two and the last two would be combined as one response. Detailed choice of questions and pooling of responses for all questions in the WVS is available upon request from the corresponding author.

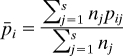

For these discrete traits, following (24), cultural FST was computed as follows. For a locus with L alleles and pij is the frequency of allele i in population j,

where

|

is the average allele frequency across s populations weighted by sample size (n) and

|

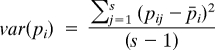

is the between group variance in variance in allele frequencies. Across all loci, the FST is

|

Cardinal responses in the WVS were treated as quantitative characters, and for each locus (question), an FST was computed from the ratio of the between group (Vg) and total variance (VT), FST = Vg/VT. The mean FST across all loci is the reported FST between a pair of populations. A full table of paired bordering countries with their genetic and cultural FST is found in the SI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Samuel Bowles and three anonymous reviewers for commenting on previous versions of this paper. This work was supported in part by a University of California Davis block grant (to A.V.B.) and National Science Foundation award 0340148.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903232106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Culture and the evolution of human social instincts. In: Enfield NJ, Levinson SC, editors. Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition, and Interaction. New York: Berg; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darwin C. The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. 2nd Ed. New York: American Home Library; 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton WD. Innate social aptitudes of man: An approach from evolutionary genetics. In: Fox R, editor. Biosocial Anthropology. New York: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander RD. The Biology of Moral Systems. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1987. p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eibl-Eibesfeld I. Warfare, man's indoctrinability, and group selection. Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie. 1982;67:177–198. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson EO. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Cambridge MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1975. p. 697. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowles S. Group competition, reproductive leveling, and the evolution of human altruism. Science. 2006;314:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.1134829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S, Richerson PJ. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3531–3535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630443100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grafen A. A geometric view of relatedness. In: Dawkins R, Ridley M, editors. Oxford Surveys in Evolutionary Biology. Vol 2. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1985. pp. 28–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price GR. Selection and covariance. Nature. 1970;227:520. doi: 10.1038/227520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton WD. The evolution of altruistic behavior. Am Nat. 1963;97:354. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank SA. Foundations of Social Evolution. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson DS, Sober E. Reintroducing group selection to the human behavioral sciences. Behav Brain Sci. 1994;17:585–654. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henrich J. Cultural group selection, coevolutionary processes and large-scale cooperation. J Econ Behav Organ. 2004;53:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehm C. Impact of the human egalitarian syndrome on Darwinian selection mechanics. Am Nat. 1997;150:S100–S121. doi: 10.1086/286052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd R. The puzzle of human sociality. Science. 2006;314:1555–1556. doi: 10.1126/science.1136841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Cultural transmission and the evolution of cooperative behavior. Hum Ecol. 1982;10:325–351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBrearty S, Brooks AS. The revolution that wasn't: A new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. J Hum Evol. 2000;39:453–563. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richerson P, Boyd R. Not by Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiten A, et al. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature. 1999;399:682–685. doi: 10.1038/21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Group beneficial norms can spread rapidly in a structured population. J Theor Biol. 2002;215:287–296. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Voting with your feet: Payoff biased migration and the evolution of group beneficial behavior. J Theor Biol. 2009;257:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Univ Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Values Study Group and World Values Survey Association. European and World Values Surveys Four-Wave Integrated Data File, 1981–2004. 2006. p. v.20060423. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bocquet-Appel JP, Demars PY, Noiret L, Dobrowsky D. Estimates of Upper Palaeolithic meta-population size in Europe from archaeological data. J Archeol Sci. 2005;32:1656–1668. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein RG. The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins. 2nd Ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999. p. 810. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs Z, et al. Ages for the Middle Stone Age of Southern Africa: Implications for human behavior and dispersal. Science. 2008;322:733–735. doi: 10.1126/science.1162219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henrich J. Demography and cultural evolution: How adaptive cultural processes can produce maladaptive losses - The Tasmanian case. Am Antiquity. 2004;69:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgerton RB. Individual in Cultural Adaptation; A Study of Four East African Peoples. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen D. Methods in cultural psychology. In: Kitayama S, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Cultural Psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. Toward a psychological science for a cultural species. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2006;1:251–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alford JR, Funk CL, Hibbing JR. Are political orientations genetically transmitted? Am Polit Sci Rev. 2005;99:153–167. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgensen JG. Western Indians: Comparative Environments, Languages, and Cultures of 172 Western American Indian Tribes. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McElreath R, Boyd R, Richerson PJ. Shared norms and the evolution of ethnic markers. Curr Anthropol. 2003;44:122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly RC. The Nuer Conquest: The Structure and Development of an Expansionist System. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1985. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beja-Pereira A, et al. Gene-culture coevolution between cattle milk protein genes and human lactase genes. Nat Genet. 2003;35(4):311–313. doi: 10.1038/ng1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richerson PJ, Boyd R, Henrich J. Cultural evolution of human cooperation. In: Hammerstein P, editor. Genetic and Cultural Evolution of Cooperation. Berlin: MIT Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly RC. The Nuer Conquest: The Structure and Development of an Expansionist System. Ann Arber: University of Michigan Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greif A. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon HA. A mechanism for social selection and successful altruism. Science. 1990;250:1665–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.2270480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richerson PJ, Boyd R. The evolution of human ultrasociality. In: Eibl-Eibesfeldt I, Salter FK, editors. Indoctrinability, Ideology, and Warfare. New York: Berghahn Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.