Abstract

The cigarette companies and their lobbying organization used tobacco industry-produced films and videos about tobacco farming to support their political, public relations, and public policy goals. Critical discourse analysis shows how tobacco companies utilized film and video imagery and narratives of tobacco farmers and tobacco economies for lobbying politicians and influencing consumers, industry-allied groups, and retail shop owners to oppose tobacco control measures and counter publicity on the health hazards, social problems, and environmental effects of tobacco growing. Imagery and narratives of tobacco farmers, tobacco barns, and agricultural landscapes in industry videos constituted a tobacco industry strategy to construct a corporate vision of tobacco farm culture that privileges the economic benefits of tobacco. The positive discursive representations of tobacco farming ignored actual behavior of tobacco companies to promote relationships of dependency and subordination for tobacco farmers and to contribute to tobacco-related poverty, child labor, and deforestation in tobacco growing countries. While showing tobacco farming as a family and a national tradition and a source of jobs, tobacco companies portrayed tobacco as a tradition to be protected instead of an industry to be regulated and denormalized.

The cigarette companies experienced increasing pressure from governments and health groups and declining public opinion beginning in the 1950s (Hobhouse 2003). Reports on tobacco companies’ practices that contribute to deforestation, mono-cropping, food insecurity, and pesticide contamination in developing countries beginning in the 1970s created additional threats to Philip Morris and British American Tobacco (BAT) (Freeman 1978; Muller 1978; Chapman and Wong 1990; Chapman 1994). Beginning in the 1970s, the tobacco industry produced films and videos on the economic benefits of tobacco growing to influence public perception of the contribution tobacco makes to tobacco growing communities and influence health policy (Table 1). Unlike tobacco advertising (Warner 1985; Broder 1992; King and Siegel 1999; Anderson, Glantz et al. 2005), there has not been a systematic study of films and videos the industry has used to promote a corporate vision of tobacco culture and support its political, public relations, and public policy goals.

Table 1.

Sample of Tobacco Industry Videos and Video Excerpts on Tobacco Economics, 1956-1999

| Title | Summary | Producer* | Date | Location** | Total Length (mins.) | Total Segment Length/Segment Used (mins.) | Segment Categories† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Plant for Tomorrow (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956) | History of the Lorillard Company, focusing on operations at its Greensboro plant | Lorillard | 1956 | Legacy | 15 | 1:00 0:00-1:00 |

CT, EJ, TIH TS |

| Leaf (Tobacco Institute 1974) | History of the growth and harvesting of tobacco in the U.S. | TI | 1974 | IA | 15 | 9:05 0:00-5:25 7:45-9:05 11:05-11:50 13:25-15:00 |

CS, CT, EJ TIH, TS |

| The Brown & Williamson Story (Brown and Williamson 1975 [inferred]) | Tobacco farming in the U.S. | BW | 1975 | IA | 12 | 2:00 0:00-2:00 |

CT, EJ, T TCFP, TIH |

| Tobacco: Seed to Pack (Philip Morris 1979) | Steps in the tobacco growing, curing, aging and manufacturing process | PM | 1979 | IA | 16 | 11:10 0:00-9:35 14:15-15:50 |

CT, EJ TIH, TFCP TS, USTB |

| Gringo Amigo (Verband der Cigarettenindustrie 1979) | Portrait of Berkeley Cohn, an agricultural tobacco extension worker in Guatemala | Verband | 1979 | IA | 12 | 12:00 | CT, DC, EJ TFCP, TS |

| Tobacco Speaks Out (Tobacco Institute 1983) | Employment in the U.S. tobacco industry | TI | 1983 | Legacy | 15 | 1:10 0:00-0:50 14:35-14:55 |

EJ, TIH |

| A Taste for Tobacco: The Story of Tobacco from Seed to Smoker (Symes 1991) | The story of tobacco from seed to smoker (Chinese Mandarin) | BAT | 1984 | Legacy | 28 | 3:25 4:50-8:15 |

ACL, CT EJ, TIH, TS USTB |

| BAT in the Developing World [Kenya] (British American Tobacco 1988) | BAT's help to tobacco farmers in Kenya | BAT | 1988 | Legacy | 8 | 8:00 | DC, EJ TFCP, TS |

| How Cigarettes Are Made (Philip Morris 1993) | Illustration of leaf processing and cigarette making | PM | 1993 | Legacy | 8 | 0:35 0:00-0:35 |

EJ, TGP, TS |

| Real Lives (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994) | Negative impact of President Clinton's proposed cigarette tax on tobacco farmers | NNSA | 1994 | IA | 7 | 3:34 0:00-2:45 5:50-6:50 |

CT, EJ, GI T, TGP, TS |

| Carolina Tobacco: Roots of an Ageless Triumph (Carolina Tobacco Company 1995) | History of tobacco farming in the U.S. | Lorillard CCC | 1995 | IA | 24 | 5:15 2:15-7:30 |

CT, EJ, TGP TIH, TS |

| Tobacco Working for America (Brown and Williamson 1996) | Overview of the financial impact of tobacco and tobacco products in the U.S. | BW | 1996 | Legacy | 11 | 3:45 0:00-3:45 |

CT, TGP TS, USTB |

| Brown and Williamson Web Site- Tobacco Processing (Brown and Williamson 1999 [inferred]) | Tobacco growing in Kentucky | BW | 1999 | IA | 9 | 5:55 0:00-5:55 |

CT, EJ, TS |

Lorillard: Lorillard Tobacco Company; CCC: Carolina Cigarette Company; TI: Tobacco Institute; BAT: British American Tobacco; PM: Philip Morris; NNSA: National Nonsmokers’ Alliance; BW: Brown & Williamson; Verband: Verband der Cigarettenindustrie (trade organization for the tobacco industry in Germany)

IA: Internet Archive; Legacy: Legacy Tobacco Documents Library at the University of California, San Francisco

ACL: alternative crops and livelihoods; CS: cigarettes and smoking; CT: culture and tradition; DC: developing countries; EJ: employment and jobs; GI: government intervention; T: taxes; TC: technology and skills; TFCP: tobacco farmer-company partnership; TGP: tobacco growing process; TIH: tobacco industry history; USTB: U.S. trade balance

Corporations, investment bankers, and international financial institutions like the World Bank influence culture and knowledge about economic life through text and visual imagery. Anthropologist Karen Ho (2005) has described how Wall Street investment bankers contribute to the cultural production of knowledge about globalization by disseminating investors’ pro-corporate perceptions of the world economy. Bret Benjamin's analysis of World Bank speeches and public documents suggests that the Bank “traffics in culture” through “rhetorical acts of public persuasion that rely on cultural formations and that appeal to cultural values” (Benjamin 2007). As a cultural institution, the World Bank has used its literature on economic development to humanize and naturalize its role in the post World War Two era and deflect criticism against the Bank's economic policies (Benjamin 2007).

Researchers have analyzed tobacco companies’ influence on cultural understandings of tobacco growing to fend off criticism, build public goodwill and resist regulation in Kenya (Currie and Ray 1984), Malaysia (Barraclough and Morrow 2008), and the U.S. (Lindblom 1999). Tobacco is associated with nostalgia about prestige and pride in agricultural communities, personal and collective identity, and memory of the past in agricultural communities and economies (Stull 2000; Ranzetta 2006). Tobacco companies draw upon these cultural associations to promote a corporate worldview of tobacco and portray companies as proponents of tobacco farmers’ interests. Tobacco companies traffic in culture. Companies use nostalgia and narrative of tobacco farm culture and the economic benefits of tobacco in films and videos to appeal to farmers and consumers and justify companies’ role in societies critical of tobacco growing and tobacco companies. Through this visual imagery, tobacco companies also portray themselves as authentic members of tobacco culture and suppress details on tobacco's contribution to death and disease.

Tobacco industry films and videos are part of $6 billion a year sponsored film industry (Solbrig 2004) with 300,000 sponsored films and videos produced in the U.S. between 1891 and 2006, far more than any other type of motion picture (Prelinger 2006). Sponsored films (also called “industrial films,” “institutional films,” “ephemeral films,” and “faux documentaries”) are ones “whose costs, including those of production, promotion, and distribution, are all paid for by a business or organization.” (Kennard 1990). The sponsored film is a non-theatrical, public relations film produced to win audiences to the funder's point of view (Klein 1976; Levin 2006; Prelinger 2006). Documentary film strategies including realism, expert talking heads and narration over archival photographs and moving images (Juhasz and Lerner 2006) are used to legitimize the sponsored film as a communications medium and to “construct ideologically informed arguments about the social world” (Solbrig 2004).

We focused on discursive narrative rather than the filmic/aesthetic composition of video to illuminate what the tobacco industry says in video to enhance its economic power and how the industry produces meanings about tobacco farmers and tobacco farming. We used critical discourse analysis to assess the video images and transcripts at the level of story structure, scene composition, and cast of characters such as a tobacco farmer and segments with farm workers harvesting tobacco (Hanjalic 2004). Discourse is a “pattern of talking and writing about or visually representing an event, object, issue, individual, or group” (Lupton 1994). Discourse is embedded in the social, economic and political contexts in which the discourse is produced and the belief systems that provide meaning to the discourse (Lupton 1994; Perakyla 2005). Discourse analysis is a tool to reveal the subtextual meanings that underpin video imagery and the relationships among media-makers, audiences, images, and social contexts (Lupton 1994; Sturken and Cartwright 2003). Health researchers have applied discourse analysis to the study of discussions between smokers and nonsmokers about smoking in public places in Canada (Poland 2000), testimony of industry, government, and lay activists on tobacco advertising regulations in U.S. Congressional hearings (Murphy 2001), and tobacco advertisements in newspapers in Spain to understand industry self-regulation as a strategy to avoid or delay effective government legislation (Martin, Quiles Mdel et al. 2004). Critical discourse analysis focuses on the meanings and relationships of power, dominance and control in written, oral, and visual language (Wodak 2004). Critical discourse analysis is committed to social justice and power relations that do not privilege one group over another based on gender, religion, ethnicity, or other social identities (Fairclough 2001; Lazar 2007).

Despite the richness of the sponsored film industry, film historians and visual researchers have neglected the sponsored film (Perkins 1982). The positive imagery of tobacco farming ignores actual behavior of tobacco companies designed to promote dependency and subordination of tobacco farmers and to contribute to tobacco-related poverty, child labor, and deforestation in tobacco growing countries. By representing tobacco farming as a family and a national tradition and a source of jobs, tobacco companies used film and video imagery to portray tobacco as a tradition to be protected instead of as an industry that needs to be regulated and denormalized.

METHODS

Tobacco Industry Film and Video Imagery

Tobacco companies produced moving pictures as 16mm and 35mm film until the 1970s, when they changed to video. (We use “video” to refer to both films and videos.) Our criteria for selecting a video for study were that it included segments on tobacco farming or farmers, growing or growers, economy or economics, employment, jobs, or developing countries, and was publicly available. We excluded product advertising, television news stories, feature films and independent (of the industry) documentaries, and Internet videos. We selected videos from approximately 6,395 tobacco industry videotapes that had been released by December 2007 as a result of litigation against the tobacco industry. The videos were indexed in the Legacy Tobacco Industry Documents Library (legacy.library.ucsf.edu) or British American Tobacco Documents Archive (bat.library.ucsf.edu). Video titles that were mentioned in tobacco industry documents, Lexus Nexus, World Cat, the University of California Melvyl library catalog, and Internet search engines (Google, Yahoo, and Clusty) were used to ensure a broad search of tobacco industry videos. Tobacco industry documents mentioned the existence of 40 videos produced by or for the tobacco industry that reflected the study themes of tobacco farming and tobacco economics. Further research showed that 27 of 40 videos never existed. We selected the remaining 13 videos as the sample based on availability, video content value, picture and sound quality, and themes of tobacco farming and tobacco economics (Table 1).

Videos in the sample of thirteen have an average length of 14 minutes and were produced between 1956 and 1999 (Table 1). Twelve of the videos are in English and one (A Taste for Tobacco) is in Mandarin Chinese; we obtained the English transcript from the industry documents (Symes 1991). We analyzed 2 complete videos and 17 video segments from the remaining 11 videos totaling 66:19 minutes. Video segments were selected from whole videos when the segment dealt with tobacco farming or tobacco economics. Segments with tobacco farming and tobacco economics were in broader stories of tobacco history and cigarette production in 12 videos.

We converted videos to digital files with Cinematize Pro 2.01 and used QuickTime Pro 7.3 and Final Cut Pro 5.3 to create Quicktime video files using compression settings with the H.264 codex, frame rate 15, bit rate 700 kbits per second, video dimensions 320 X 240 pixels, and AAC audio format. We obtained transcripts from the industry documents (Concept Films and Tobacco Institute 1974; Symes 1991) (2 videos) or by preparing our own verbatim transcripts (11 videos).

We watched each video with transcript in hand at least three times to understand the story, document each new cut, or “shot” that demarcates the endpoints of a segment, and mark relevant images in every segment (Jernigan and Dorfman 1996).

We related the results from the analysis to the findings of written text analysis of video transcripts that we conducted by crosschecking for patterns of tobacco culture and economics from the 1950s to 2007 in industry arguments, statements, and practices, and in related literature. We combined critical discourse analysis with ethnographic content analysis to decipher narratives from the videos and situate the narratives in the broader social, economic, and political contexts. We focused on video narratives and discursive representations to illuminate how the industry understands itself and responds to threats to the smoking business. We used ethnographic content analysis to create a detailed explanation and description of video images through tobacco industry documents with details on the videos (Jernigan and Dorfman 1996; Dimitrova, Zhang et al. 2002; Hanjalic 2004). Ethnographic content analysis is a method for making inferences from visual text to the contexts in which text is produced and used (Hirsch 1996; Jernigan and Dorfman 1996). Ethnographic content analysis is grounded in “an orientation toward constant discovery and constant comparison of relevant situations, settings, styles, images, meanings, and nuances” (Altheide 1987). We used the categories of culture and tradition, tobacco industry history, employment and jobs, taxes, U.S. trade balance, technology and skills, alternative crops and livelihoods, tobacco growing process, cigarettes and smoking, government intervention, tobacco farmer-company partnership, and developing countries to organize video imagery and analyze their meanings and contexts.

We also used the tobacco industry documents to identify the companies’ intentions and uses of the videos and the context of tobacco industry videos. We searched with terms “video,” “film,” “economic benefits,” and “tobacco farming.” Follow-up searches using standard snowball approaches to locating and screening documents (Malone and Balbach 2000; Balbach 2002) were done based on adjacent pages (Bates numbers) for relevant documents and the names of key individuals and organizations identified in previous searches. We screened 1,864 documents and used 18 for this analysis.

RESULTS

Tobacco companies were early adopters of film to promote their products and interests. In 1897, the Edison Manufacturing Company produced the silent film Admiral Cigarette (30 seconds) (Prelinger 2006). Admiral Cigarette is one of the first advertising films in the world (Prelinger 2006). In 1938, the Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company produced Tobaccoland about cigarette production in the 1930s. In a magazine advertisement promoting its services, Castle Service, Liggett and Myers’ film distributor, reported that, “In only eighteen months [Tobaccoland] was shown to more than twenty-two million men and women!” (Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company 1944). Early examples of tobacco industry films and subsequent tobacco industry videos focus on corporate culture and public relations strategies. The films and videos represent recorded history of tobacco industry practices, and document changing tobacco industry arguments on the economic benefits of tobacco growing.

Promotion of Positive Industry Images to Counteract Negative Public Perceptions of Smoking and Smoking Restrictions

Following the increase in publicity on the negative health effects of smoking in the 1950s, Lorillard Tobacco Company produced the classroom educational film A Plant for Tomorrow in 1956 (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956). A Plant for Tomorrow features the company's history and its automated plants in Greensboro, North Carolina (Figure 1) (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956). The black and white film begins with the title over a small group of farm workers and a horse in a tobacco field. African American farm workers wear work shirts and trousers without protective clothing, which was typical in the 1950s. Dramatic music plays over the segment until the narrator says, “From our earliest beginnings, first as a colony and then as a nation, tobacco has been inseparably bound with our history. As our country won independence and flourished, so did the tobacco industry grow and prosper. And the story of the company founded in 1760 by a young juggernaut Pierre Lorillard is virtually the history of tobacco manufacturer in America” (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956).

Figure 1.

A Plant for Tomorrow. Lorillard Tobacco Company, 1956. Editor suggested we reduce text in captions. Format follows standard of Visual Anthropology Review.

The segment uses major symbols and spaces of rural life and tobacco farming to show the value of tobacco to individuals, families and communities, tobacco as a labor-intensive crop, and the collective work process. Lorillard, through the juxtaposition of the title over a harvesting scene, suggests that the future of tobacco growing and tobacco companies is secure in the 1950s and beyond (A Plant for Tomorrow!). The subtext of the title screen and African American farm workers is that tobacco is an economically viable, labor-intensive crop the tobacco industry uses to mask relationships of dependency and subordination. A Plant for Tomorrow features common symbols and spaces that signify tobacco culture such as tobacco fields, drying sheds filled with tobacco, and freshly plowed land. Lorillard appropriates these spaces to present itself through video imagery as an authentic stakeholder in the welfare of tobacco farmers. The company uses tobacco symbols and spaces to create perceptions of trust and empowerment to influence people to overcome internal conflict they may have over tobacco and smoking in society.

The segment in A Plant for Tomorrow also reveals the racialized dimension of imagery with depictions of African Americans as hired hands and continued relations of exploitation. The segment and imagery suggest that little has changed for African Americans in the rural South since the Civil War. Lorillard's nostalgia for tobacco history ignores the fact that African Americans slaves were forced to devote their labor to tobacco farming beginning in the 1700s, and subsequently tied to tobacco through unfair sharecropping arrangements after emancipation (Table 2) (Daniel 1985; van Willigen 1998). Imagery in the segment does not show the long hours of stoop labor, harassment of workers by farm authorities, abject poverty, staggering debt, exposure to nicotine and pesticides, and poor health of workers and farmers that characterize the inequalities of tobacco farm culture (Farm Labor Organizing Committee 2007). Discourses and imagery from A Plant for Tomorrow contain the primary message that tobacco is imbued with nostalgia about agricultural history and economy. The discourses and imagery also contain the primary message that people who promote tobacco control threaten tobacco families and national values in the U.S. Lorillard produced a master narrative of the benefits of tobacco farming that intersects with other discourses about the protection of tobacco farm culture, the economic empowerment of communities through tobacco farming, and the association of tobacco with patriotism and nationalism.

Table 2.

Unfair Portrayals of Tobacco Farming in Tobacco Industry Videos

| Categories | Video Title | Year | Portrayals of Tobacco Farming in Tobacco Industry Videos | More Accurate Portrayals of Tobacco Farming in Industry Videos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture and Tradition | A Plant for Tomorrow (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956) | 1956 | “[Tobacco is] part of our heritage. This is our bread-and-butter crop.” | Tobacco farm culture is characterized by long hours of stoop labor, abject poverty, staggering debt, exposure to nicotine and pesticides (Farm Labor Organizing Committee 2007). |

| Brown and Williamson Web Site- Tobacco Processing (Brown and Williamson 1999 [inferred]) | 1999 | “Stripping tobacco has become a family tradition. With the check from tobacco sales at auction, the farmer pays his bills, provides for his family, and gets ready for the holidays, and starts buying seeds and fertilizer for next years crop.” | Tobacco companies ensure farmer subordination through inflated prices for farm inputs and fields for tobacco instead of food crops (Loker 2004; Gostin 2007). | |

| Tobacco Industry History | A Plant for Tomorrow (Lorillard Tobacco Company 1956) | 1956 | “From our earliest beginnings, first as a colony and then as a nation, tobacco has been inseparably bound with our history. As our country won independence and flourished, so did the tobacco industry grow and prosper.” | Tobacco history intersects with enslaved African Americans involved in tobacco farming beginning in the 1700s, and unfair sharecropping arrangements in the 1900s (Daniel 1985; van Willigen 1998). |

| Tobacco Speaks Out (Tobacco Institute 1983) | 1983 | “[Tobacco] is in fact, America's oldest industry dating back to the early 1600s when John Roll, better known as the husband of Pocahontas became America's first tobacco farmer and exporter.” | The tobacco industry obtained its economic influence over farmers through a monopoly and monopsony of tobacco buyers since the industry was established (Algeo 1997; Craig 2005). | |

| Employment and Jobs | The Brown and Williamson Story (Brown and Williamson 1975 [inferred]) | 1975 | “[W]hen you count all the people who grow the tobacco and those who manufacture it, distribute it, and sell it, you've got 17 million Americans for all or part of their income.” | Tobacco companies ignore annual health-related economic costs of $167 billion, including adult death-related productivity costs, adult and newborn medical expenditures (American Cancer Society 2007). |

| Tobacco: Seed to Pack (Philip Morris 1979) | 1979 | “[Tobacco] provides jobs for two million Americans. 600,000 farm families receive income from the production of tobacco. | U.S. tobacco companies harm local tobacco farmers by increasingly growing, processing, and making cigarettes overseas beginning in the 1970s (Lindblom 1999). | |

| Taxes | The Brown and Williamson Story (Brown and Williamson 1975 [inferred]) | 1975 | “Annual taxes collected on the sale of tobacco products are well over $5 billion.” | Smuggled illegal cigarettes deny governments $40 to $50 billion in taxes each year (Framework Convention Alliance 2007). |

| Real Lives (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994) | 1994 | “Nationwide, the tobacco industry employs more than 2.3 million people, who along with industry, pay more than $39 billion in taxes.” | Tobacco companies paid $2.9 million to state lobbyists in the U.S. in 1997 to minimize tax increases and weaken state tobacco control policies (Givel and Glantz 2001). | |

| U.S. Trade Balance | Tobacco: Seed to Pack (Philip Morris 1979) | 1983 | “A significant part of American tobacco and tobacco products is shipped out of the country. Each year these international sales contribute a positive foreign trade balance of more than $1.7 billion to our economy.” | U.S. tobacco companies hurt U.S. tobacco farmers by purchasing inexpensive tobacco from developing countries, paying low tobacco prices to U.S. farmers, establishing cigarette manufacturing plants abroad, and entering new markets outside the U.S. (Johnson 1994). |

| A Taste for Tobacco: The Story of Tobacco from Seed to Smoker (Symes 1991) | 1984 | “America's been wrestling a lot lately with foreign trade, balance of payments, exported jobs, and imported products. Tobacco gives us a trade surplus of $6 billion.” | In 1984, U.S. tobacco companies lobbied the U.S. government to oppose high tariffs and high retail taxes in Asia in tobacco-related global trade disputes (Shaffer, Brenner et al. 2005). | |

| Technology and Skills | Leaf (Tobacco Institute 1974) | 1974 | “From seed beds to barning, to grading leaf for auction sales, good tobacco depends largely on the hands, the eyes, the skills of those who understand this temperamental plant.” | Tobacco farmers and workers suffer from bladder cancer, allergic or irritant skin disorders (contact eczema), and pesticide exposure (Schmitt, Schmitt et al. 2007) |

| BAT in the Developing World [Kenya] (British American Tobacco 1988) | 1988 | “[A tobacco farmer in Kenya] realizes that [BAT] will instruct him in new agricultural methods which are relevant to his needs. At the same time, traditional skills such as plowing with oxen are not forgotten if they represent the most appropriate technology.” | A tobacco farmer in Kenya said, “The loan the tobacco firm provides is really weighing down on us. Actually, after the deduction you get nothing. Year in year out of the company ensures that you have an outstanding loan” (Patel, Collin et al. 2007). | |

| Alternative Crops and Livelihoods | A Taste for Tobacco: The Story of Tobacco from Seed to Smoker (Symes 1991) | 1984 | “[T]obacco is not an easy crop to grow for it requires more than 270 hours of labor per acre. In contrast, an acre of wheat needs only three and half hours of labor.” | U.S. tobacco farmers successfully diversified to organic bell peppers, tomatoes, and dozens of other heirloom vegetables (Halweil 2003), and in many cases, replacement crops demand as much if not more labor than tobacco (Warren 2002). |

| A Taste for Tobacco: The Story of Tobacco from Seed to Smoker (Symes 1991) | 1984 | “[T]he tobacco plant is from the same family as the tomato, pepper, potato and petunia.” | The tobacco plant contains nicotine, a substance responsible for cigarette addiction and 490,000 tobacco-related deaths in America each year (Institute of Medicine 2007). | |

| Tobacco Growing Process | How Cigarettes Are Made (Philip Morris 1993) | 1993 | “The process of making cigarettes begins in the field, where the tobacco is grown and harvested.” | Tobacco companies alter and manipulate nicotine levels to ensure cigarette addiction and marketplace viability of tobacco products (Hurt and Robertson 1998). |

| Carolina Tobacco: Roots of an Ageless Triumph (Carolina Tobacco Company 1995) | 1995 | “At maturity, the burley plants stand about two meters tall. It is harvested whole stalk and speared on stakes usually 5 to 6 stalks each. Stakes are positioned so the severed end of the stalk faces the sun at its greatest intensity to provide maximum protection to the leaves.” | Tobacco workers suffer from green tobacco sickness due to nicotine poisoning from dermal nicotine absorption, leading to vomiting or nausea during or after exposure. The cumulative seasonal exposure to nicotine of workers in tobacco fields is equivalent to smoking 180 cigarettes (Schmitt, Schmitt et al. 2007). | |

| Cigarettes and Smoking | How Cigarettes Are Made (Philip Morris 1993) | 1993 | “The unique taste of American cigarettes is a result of the blending of burley and bright tobaccos, which have different characteristics.” | Tobacco companies use expanded and reconstituted tobacco with nitrogen, isopentane, and liquid carbon dioxide additives to puff up discarded tobacco to use in cigarettes (Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids 2001). |

| Tobacco Working for America (Brown and Williamson 1996) | 1996 | “Today, approximately 45 million Americans enjoy tobacco products from plants grown in fields like this one.” | Cigarette consumption is declining 1.5% each year in the U.S. and increasing 2.1% a year in developing countries, where inadequate health care systems exist and restrictions on tobacco companies are virtually absent (Warner 2000). | |

| Government Intervention | Real Lives (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994) | 1994 | “To raise only a tiny portion of what [President Clinton's administration] need[s] to fund health care reform, the administration has chose to place an unfair burden on not only the 15 million adults who choose to smoke but on an industry that has been the backbone of American society since colonial times.” | Tobacco companies place an unfair burden on 38,000 nonsmokers who die each year due to exposure to secondhand smoke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005). |

| Real Lives (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994) | 1994 | “From plant workers, to farmers to convenient store workers people all over the country real people with jobs and lives that depend on decisions that you could make or influence wait for the outcome of the health care reform battle with mixed emotions. They want health care for all Americans, but they don't want to be singled out for unfair taxation.” | Health Professor Gary Giovina said, “1 year of [tobacco-related] employment comes at the expense of one person losing 15 years of life from a disease caused by the product supporting the job. Because money not spent on tobacco would be spent on other goods and services, the job is replaceable. The life, however, is not” (Giovino 2007). | |

| Farmer-Company Partnerships | Tobacco: Seed to Pack (Philip Morris 1979) | 1983 | “[Tobacco] contributes to America in a positive tangible way financially. It is able to do so because of a successful partnership between manufacturer and grower. .” | In 2003, tobacco companies opposed U.S. government recommendations to provide economic development assistance to tobacco communities; tobacco growers supported the Commission's report and recommendations (The President's Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Public Health 2001; Myers 2003). |

| BAT in the Developing World [Kenya] (British American Tobacco 1988) | 1988 | “[BAT] agricultural extension workers visit the farmers on a regular basis providing advice on how to improve the quality of all their crops not just tobacco.” | BAT, other tobacco companies, and leaf buying companies provide seeds and fertilizers on loan to farmers in Kenya and elsewhere, pushing farmers into debt, poverty, and in extreme cases, desperation leading to suicide from pesticide exposure or unfulfilled contract arrangements with leaf companies (Christian Aid 2002; La Via Campesina 2007; Patel, Collin et al. 2007). | |

| Developing Countries | Gringo Amigo (Verband der Cigarettenindustrie 1979) | 1979 | “Berkeley Cohn has been living in Guatemala for the past five years. He speaks Spanish. And since he wasn't willing to simply accept their poverty and misery, he decided to do something about it all by himself. Berkeley is financing the schooling of Ricardo Perez’ youngest son, Gandalfo, from his own pocket.” | Similar to anthropologist Dinah Rajak's findings on mining companies in South Africa (Rajak 2006), tobacco companies in Guatemala and other developing countries conceal their power over farmers and economies with claims that tobacco companies are synonymous with empowerment and sustainable development. |

| BAT in the Developing World [Kenya] (British American Tobacco 1988) | 1988 | ““[In Kenya] BAT has worked hard to improve farming methods which have led to higher standards of living for rural Kenyans.” | BAT contributes to poverty through tobacco-related deforestation, soil erosion, chemical contamination of water tables, farmer indebtedness to BAT, and child labor in Kenya and other tobacco growing countries (Eldring, Nakanyane et al. 2000; Chacha 2003). Clearing land for tobacco amounts to 500,000 acres cleared every year worldwide (Geist 1999; Esson and Leeder 2004). |

The Tobacco Institute and the Development of a Tobacco Industry Video Strategy to Weaken Health Policy

The industry developed a strategy to use film types such as documentaries for lobbying policy makers to oppose tobacco-related regulations or for advancing public relations goals in 1969 (Tiderock Corporation 1969 i[nferred]). In 1969, the Tobacco Institute (the tobacco industry's lobbying and public relations arm) requested “A Film Program” from the Tiderock Corporation (Tiderock Corporation 1969 [inferred]) (one the Institute's public relations agencies) that refined the industry's strategy to use films and videos to influence public opinion and health policy. Tiderock listed the public health films opposed to smoking produced by the American Cancer Society and other health groups in the 1960s, and suggested that, “the Tobacco Institute could make many effective uses of a fully up-to-date, objective, authoritative- and lively-documentary film that dramatizes ‘the other side’ of the controversy [that the industry was seeking to create about the health effects of smoking (Clements 1968)] for general audiences” (Tiderock Corporation 1969 [inferred]). The film-based strategy that Tiderock recommended had multiple parts:

In half-hour form, such a film could serve valuably as the core of personal presentations to adult civic, social, business and professional groups by Institute and intra-industry representatives, including medical speakers. The film could have nationwide exposure to the desired organized adult audiences even without an accompanying speaker, through distribution as a self-contained feature for one of their regular meetings. The film might be shown in theatrical and other settings where “captive” potential audiences congregate -- i.e., resort hotels, airports, etc. Although many complexities may be involved, television exposure of the film should also be explored (Tiderock Corporation 1969 [inferred]).

In 1970, the Tobacco Institute implemented this strategy (Duffin 1970). In 1972 the Tobacco Institute produced the film Smoking and Health: The Need to Know “to demonstrate that evidence linking smoking and health problems is far from conclusive” (Tobacco Institute 1972). A confidential memo from Andrew Whist (corporate affairs manager with Philip Morris Australia) to Alexander Holtzman (a Philip Morris lawyer in New York and company liaison to the Tobacco Institute) said of Smoking and Health, “Irrespective of the attitude of legislators and scientists before and after seeing the documentary, there can be no doubt that it does open dialogue with interested parties, a dialogue which we did not have previously” (Whist 1974). The tobacco industry's video strategy also focused on establishing a dialogue with tobacco farmers and others whose livelihoods depended on tobacco to recruit them as allies in arguments about the economic benefits of tobacco (Mayes 1974).

“We've grown tobacco ever since tobacco has been grown. It's part of our heritage.”: The Tobacco Institute's Leaf Video

Leaf is an example of a video the Tobacco Institute produced and distributed in 1974 (Figure 2) (Tobacco Institute 1974). Leaf is comprised of scenes of family members harvesting tobacco, meeting the family's subsistence needs through tobacco earnings, and honoring the memory of previous generations who passed down crop husbandry skills (Tobacco Institute 1982). In 1984, a representative of the Modern Picture Talking Service (which helped the Institute distribute its videos) reported to the Institute that Leaf was the Institute's “most heavily viewed and requested film” among its for major films in circulation. Leaf reached 26,879 average monthly viewers and received 526 average monthly bookings from cable television stations, public schools, and other groups in the U.S. in 1984 (Tobacco Institute 1984).

Figure 2.

Leaf. Tobacco Institute, 1974.

In a segment from Leaf on a North Carolina tobacco farm, a white middle-aged male farm owner wearing a baseball cap and a short sleeve collar shirt is interviewed. In the background, a small group of African American and Latino workers and an individual that may be a family member of the farmer prepare a load of tobacco.

Tobacco farmer: We've grown tobacco ever since tobacco has been grown. It's part of our heritage.

Narrator: Gerald Aycock and his family farm in Eastern North Carolina. Aycocks have been growing Virginia leaf for flue-cured tobacco since the 1600s. What accounts for the dedication of those who raise it for years, for generations?

Tobacco farmer: It's part of our heritage. This is our bread and butter crop (Tobacco Institute and Philip Morris 1974).

The segment from Leaf reflects the Tobacco Institute's efforts to promote the benefits such as jobs from tobacco (Tobacco Institute 1974). The segment reflects the Tobacco Institute's efforts to appeal to tradition and economic contribution of tobacco to farming communities and the national economy to counter negative public perceptions of the tobacco industry. In a segment on tobacco economics in Leaf, the narrator says, “Today this plant, with its enormous impact on the life and cultures of people of all lands, remains one of the most demanding of crops to grow” (Tobacco Institute 1982). The subtle meanings of video imagery of tobacco farmers and farm workers in Leaf demonstrate tobacco industry efforts to characterize tobacco as a socially important crop and hide behind tobacco culture and economics to normalize tobacco. Imagery in the segment of African Americans and Latino farm workers confers the racialized dimension of tobacco culture and history. Imagery in the segments shows the industry's role in legitimizing and naturalizing race and class inequalities at the farm level. The Tobacco Institute, through Leaf, also promoted its own vision of tobacco culture that privileged tobacco as a family farm affair and a contributor of wealth in the U.S. The Tobacco Institute promoted its tobacco culture vision while excluding details on the loss of workforce productivity and health care costs due to tobacco-related death and disease.

Tobacco Companies Use Video Imagery to React to Criticism of Tobacco Production Practices in Developing Countries

At the same time that U.S. cigarette consumption started to decline in 1981 for the first time (Lindblom 1999), tobacco companies were expanding efforts that began in the 1970s in developing countries to open cigarette factories, advertise smoking to women and children, and obtain low cost tobacco (Ensor 1992; Stebbins 1994). From 1970 to 2000, tobacco leaf production doubled in developing countries, compared to a 36% increase in developed countries (Davis, Wakefield et al. 2007) and reached 90% of the world's tobacco in 2006 (Food and Agriculture Organization 2008).

In his 1978 study, Mike Muller found that tobacco companies were marketing and selling cigarettes in developing countries with tar levels that were twice that in cigarettes available in Britain (Muller 1978). He reported that tobacco cultivation was steadily increasing in developing countries, aggravating deforestation, food insecurity, and seasonal unemployment as food crops decreased from labor being diverted to tobacco (Muller 1978). In 1979, the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded that tobacco growing is “far from sound as an economic activity,” global tobacco exports needed to be discouraged, the size of tobacco growing and manufacturing industries should be reduced, and “no country should allow a tobacco growing or manufacturing industry to be developed. Where such an industry exists, priority should be given to the development of substitute crops, with international cooperation” (Tobacco Institute [inferred] 1979; World Health Organization 1979).

To counter these criticisms, Verband der Cigarettenindustrie (the German cigarette manufacturers’ trade organization) used the grower-manufacturer partnership theme in the narrative structure of its Gringo Amigo (“white friend”) in 1979 to present a positive image of tobacco companies in developing countries (Figure 3) (Verband der Cigarettenindustrie 1979). Gringo Amigo focuses on Berkeley Cohn (a German national who speaks Spanish in the video, and is an agricultural extension worker with an unnamed tobacco company) to depict efforts in Guatemala's tobacco growing areas to reduce poverty and bring peace through tobacco production. Philip Morris or BAT (the only cigarette manufacturers in Guatemala) may have employed Cohn. Philip Morris and BAT provide financing, equipment and agrochemicals for tobacco growers in Guatemala and control Guatemala's cigarette market (Foreign Agricultural Service 1995). In contrast to arguments that tobacco growing harms farmers and environments in developing countries, still images of Cohn and a child farm laborer from Gringo Amigo communicate the positive social and economic influence of tobacco companies in developing countries. The images communicate the benevolence and control over individuals and communities that companies rely on to ensure access to tobacco produced by unpaid or underpaid laborers.

Figure 3.

Gringo Amigo. Verband der Cigarettenindustrie, 1979.

Gringo Amigo portrays the farmer-manufacturer partnership as based on recommendations from Cohn to farmers to be economically productive and peaceful citizens. Cohn speaks with tobacco farmers about the value of saving money and ensuring that their children attend school. Cohn takes two tobacco farm laborers to visit a banker to show the laborers the money they saved and earned by depositing some of their tobacco money in savings for one year rather than spending it on alcohol and gambling. Later, the narrator explains that Cohn pays for the schooling of Gandalfo, the youngest son of tobacco farmer Ricardo Perez, and two sons of tobacco farmer Lopez Brocomontare. According to the narrator, Cohn “is ashamed of the social injustice of the country's long dependence on the United States has left behind.” The narrator continues,

Sometimes, this young foreigner, the gringo, feels anger rising up inside him. Anger at the injustice he sees in this country he loves. He says that until these people learn that their worst enemy is ignorance, neither he nor anyone else will be able to help. The path they have to take is a long one. Poverty and ignorance produce fear. Fear, in turn, causes despair. And despair could be dynamite. Berkeley does not believe that violence is the answer. He knows just how patient these simple people are. How ready they are just to wait. Don't resort to violence he says to his friends but just waiting won't get you anywhere either (Verband der Cigarettenindustrie 1979).

Associations with paternalism and benevolence in Guatemala's tobacco sector evoke companies’ roles as a friend and partner of tobacco farmers. The depiction of tobacco companies as a benevolent force represents an idealized corporate self-representation. The depiction represents symbolic industry recognition of tobacco's demise in the U.S. and increasing cultural and economic presence in developing countries. The tobacco companies’ capacity to profit through low-cost tobacco during Guatemala's wartime while recruiting new smokers in disenfranchised communities makes companies’ roles analogous to an exploiter of individuals and environments in developing countries and a vector for tobacco-related death and disease (Yach and Bettcher 2000; Chapman 2006).

Video Imagery of the Economic Benefit of Tobacco to Farmers and the U.S.

In 1979, following global condemnation by health and social advocates of the tobacco industry's production practices in developing countries, Philip Morris produced Tobacco: Seed to Pack apparently to promote positive industry practices among politicians and consumers in the U.S. (Figure 4) (Philip Morris 1979). According to Tobacco, “Tobacco contributes $50 billion a year to the nation's economy. In the process, it provides jobs for two million Americans. 600,000 farm families receive income from the production of tobacco. It's the number one cash crop in North and South Carolina, and Kentucky. Number two in Georgia and Virginia and fourth in Tennessee. Tobacco farmers earn their money” (Philip Morris 1979). In the video Philip Morris conveys messages about hardworking farmers and the American spirit originating in the soil on tobacco farms. Philip Morris promotes the messages with narration “Tobacco farmers earn their money” and imagery of rural families, agricultural landscapes, and farm revenues. The messages represent Philip Morris’ attempt to create an authentic view of tobacco's cultural heritage. Tobacco also discussed the contribution of tobacco to the U.S. trade balance:

A significant part of American tobacco and tobacco products is shipped out of the country. Each year these international sales contribute a positive foreign trade balance of more than 1.7 billion dollars to our economy. That's symbolic of our tobacco industry. It contributes to America in a positive tangible way financially (Philip Morris 1979).

Figure 4.

Tobacco: Seed to Pack. Philip Morris, 1979.

Tobacco featured the labor required to cultivate tobacco and discussed tobacco as a superior crop to wheat based on the labor required to produce tobacco. “[Tobacco] is not an easy crop to grow for it requires more than 270 hours of labor per acre. In contrast, an acre of wheat needs only three and a half hours of labor” (Philip Morris 1979). Contrasting the hours of labor for tobacco and wheat characterizes tobacco as a dominant crop that strengthens industry arguments about the absence of viable crops and livelihoods to replace tobacco. The subtext of still video images of hand labor on tobacco farms shows Philip Morris’ efforts to humanize the company and use “tobacco crop” as a discourse of economic empowerment portrayed as a social fact. The underlying message of Tobacco is that crop substitution projects are ineffective and tobacco remains the ideal crop for jobs and economic vitality.

In contrast to the images in Tobacco, industry practices show disdain for tobacco farmers and farm culture. Tobacco companies downgrade (assign a lower quality, and so a lower financial value, to) tobacco, promote large scale farms over family farms and use scare tactics to argue that tobacco communities “will live or die by tobacco and nothing else” (Johnson 1994). Companies’ purchases of low-cost tobacco from developing countries and use of foreign tobacco in U.S. manufactured cigarettes (Lindblom 1999; Reaves and Purcell 1999) contradict companies’ images in Tobacco and other videos that the tobacco companies are partners with domestic farmers to protect the tradition of tobacco (Table 2).

In 1983, the Tobacco Institute produced Tobacco Speaks Out about the public relations activities of the Tobacco Institute with segments on the importance of people involved in tobacco production to distance tobacco use from death and disease (Figure 5) (Tobacco Institute 1983). The opening segment shows a tobacco auction overlaid with onscreen text, “The following is a presentation of the Tobacco Institute in the belief that a free, full, and informed discussion of all issues involving tobacco is in the public interest.” The segment supports the industry argument that public health and media discussions unfairly exclude it and misrepresent its positions (Saloojee and Dagli 2000; Smith and Malone 2003). A secondary meaning of the onscreen text reflects the industry strategy of portraying itself as a reasonable partner in public debates about tobacco economics. Tobacco companies’ support for “a free, full, and informed [public] discussion of all issues involving tobacco” in Tobacco Speaks Out, shows that tobacco industry nostalgia for farm culture is imbued with rhetorical acts of public persuasion and a corporate vision of tobacco culture veiled in neutrality.

Figure 5.

Tobacco Speaks Out. Tobacco Institute, 1983.

In a segment on tobacco economics in the Tobacco Speaks Out, the Tobacco Institute uses tobacco employment data from industry consultants at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School to argue the economic importance of tobacco in the U.S.: “[T]hroughout history, tobacco has meant one thing more than any other, people. In the fields, in the factories, and all kinds of places in between. A study by the University of Pennsylvania's highly respected Wharton School reveals in America today tobacco means jobs to more than 2 million people. But today, this golden leaf also means something else. In its own interest certainly, but also in the public interest America's oldest industry is speaking out” (Tobacco Institute 1983). The tobacco industry uses economic figures from tobacco industry-funded studies from university researchers at the Wharton School and consulting firms such as PriceWaterhouse to give credence to industry economic arguments (Warner, Fulton et al. 1996; Cohen, Ashley et al. 1999).

Tobacco industry-funded analyses do not take into account the cost to society from tobacco production and consumption, particularly costs of tobacco use for the health care sector, and inflate tobacco-related job losses due to tobacco control measures that reduce tobacco employment in communities reliant on tobacco farming (Warner 1987). In Tobacco Speaks Out, the Tobacco Institute featured research that inaccurately reported tobacco-related jobs and incomes as irreplaceable and understated tobacco-related costs for health care and the mortuary business (Warner 1987). The Tobacco Institute and the tobacco industry rely on employment and other economic data from industry-funded consultants to argue the economic contribution of tobacco to farming communities.

BAT Claims of Development and Environmental Stewardship in the Video BAT in the Developing World [Kenya]

In 1988, BAT focused on its economic partnership with tobacco farmers in Kenya in BAT in the Developing World on the company's contract farming arrangements, reforestation schemes and agricultural extension assistance to tobacco farmers in Kenya (Figure 6) (British American Tobacco 1988). BAT in the Developing World is a set of three videos that focus on tobacco growing and reforestation in Kenya, Sri Lanka and Brazil. We were only able to obtain the Kenya episode. According to the video, BAT “has been working with tobacco farmers in developing countries for several generations. Understanding their needs is not only good for our business, it's good for theirs” (British American Tobacco 1988). Kenya is one of Africa's most important growers of tobacco and producers of cigarettes (Patel, Collin et al. 2007). BAT directly contracts 8,000 tobacco farmers in Kenya (British American Tobacco 2004).

Figure 6.

BAT in the Developing World [Kenya]. British American Tobacco, 1988.

BAT in the Developing World discusses the links between contract farming and farmer welfare. According to the narrator, BAT “helps to arrange loans to meet their capital costs and underwrites their credit with the bank” (British American Tobacco 1988). The video suggests that BAT loans contribute to the farmer's economic sustenance and ability to learn new agricultural methods through BAT representatives. The video suggests that farmers enjoy the increasing yields from tobacco crops through the use of fertilizers purchased from BAT. According to the video, relationships of farmers with BAT contribute to the maintenance of traditional agricultural practices, prevention urban migration from rural areas in Kenya, and application of farm chemicals to increase tobacco yields. BAT interviews Mr. Mowita, government minister and tobacco farmer in Kenya, on the company's reforestation scheme, as a strategy to humanize and legitimize BAT's environmental stewardship in Kenya.

Very little of this tree planting, but in 1979, BAT started because they saw the effect that without encouraging the farmers from planting trees the areas will remain death paths. Therefore, up to last year the total number of trees planted in my area is about 4 million. And this is quite a big contribution than the government policies. BAT is also encouraging the farmers to have their own seed beds, an average per farmer of about 200-500 trees which to me if you come back to this country in another four years time you'll see tremendous. The landscape will be beautiful...power...from BAT and supplemented by others I think...I'm happy when I see my people and look forward to buy small vehicles to transport other people. Their condition of living has improved. I think BAT to me and I think to not only to me to all the farmers and people at home they are quite grateful to BAT (British American Tobacco 1988).

Latent meanings of the excerpt on BAT's tree planting and video still images of tobacco warehouse workers and a farmer consulting with a BAT agricultural extension officer in a field reveal that BAT portrays itself as a contributor to socioeconomic development and partner in reforestation programs to conceal BAT's role in tobacco-related poverty in developing countries. In the interview with Mowita, BAT depicted farmers’ and government officials’ gratitude for BAT's reforestation effort and environmental stewardship in Kenya. Beginning 1982, opposition emerged to raise public awareness of BAT's contribution to deforestation and land degradation in Kenya (Currie 1984; Kweyuh 1994; Bazinger 1187). BAT's video imagery constitutes a corporate activity to build public faith and neutralize opposition to tobacco company practices in Kenya.

BAT promoted imagery of tobacco as a driver of socio-economic development when actual companies’ practices such as contract farming hurt tobacco farmers’ social and economic lives. In BAT in the Developing World, BAT claims that contract farming contributes to social and economic development of tobacco farmers in Kenya. Problems with contract farming include inflated prices for seeds and agricultural chemicals and little or no financial benefits with high risks for tobacco farmers (Patel, Collin et al. 2007). Problems with contract farming include indebtedness of farmers to companies who provide agricultural inputs on loan, and monopolistic leaf buying practices that enable companies to underpay and control local farmers (Patel, Collin et al. 2007). Joe Asila (founder of Kenya's Social Needs Network) reported that many tobacco farmers in Kenya who did not understand the contracts signed the contracts (Asila 2004). Asila said that, “80 per cent of tobacco farmers [in Kenya] actually lose money. Because they are usually poorly educated, they lack the skills to organize a budget for their nine months of toil. When the payoff comes they see the cash-in-hand, not the loss they may have incurred. Their only certainty is that tobacco farming does little to improve their hand-to-mouth existence” (Asila 2004). BAT's images of tobacco's contribution to higher living standards for farmers in Kenya and other tobacco growing countries portrayed in videos such as BAT in the Developing World are contradicted by the poverty and chronic indebtedness of tobacco farmers, and, in extreme cases, desperation leading to suicide from pesticide exposure or unfulfilled contract arrangements with tobacco companies (Table 2) (Christian Aid 2002; World Health Organization 2004; Otañez, Muggli et al. 2006; La Via Campesina 2007; Patel, Collin et al. 2007).

Potential Tobacco Regulation and Tax Increases Threaten Tobacco Companies

In 1993, U.S. President Bill Clinton proposed a $0.75 per pack cigarette tax increase as part of health care reform legislation that would have guaranteed every American private health insurance (Schroeder 1993).

In 1994, the National Smokers’ Alliance, a front group Philip Morris created to oppose tobacco control legislation (Stauber and Rampton 2004), produced Real Lives as a response to Clinton's proposed tax increase, arguing that it would hurt tobacco farmers (Figure 7) (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994). According to Real Lives, “The Administration has chose to place an unfair burden on not only the 15 million adults who choose to smoke but on an industry that has been the backbone of American society since colonial times” (National Smokers’ Alliance 1994). Tobacco industry support for an end to unfair attacks on adult smokers in Real Lives illustrates industry efforts to appeal to viewers’ empathy for companies’ arguments and to promote a corporate worldview of tobacco culture.

Figure 7.

Real Lives. Philip Morris, 1993.

Tobacco companies convinced tobacco farmers in the U.S. to lobby against President Clinton's proposed tobacco tax when in reality tobacco companies hurt farmers more than the proposed tobacco tax would have ever done (Johnson 1994). In 2003, tobacco companies opposed the recommendations of the President's Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Health with recommendations such as providing economic development assistance to tobacco communities to create non-tobacco jobs, income and wealth (Table 2) (The President's Commission on Improving Economic Opportunity in Communities Dependent on Tobacco Production While Protecting Public Health 2001; Myers 2003). In contrast, tobacco growers supported the Commission's report and recommendations. Video imagery of the economic benefits of tobacco for farm communities ignores the tobacco companies’ opposition to the Commission's report and recommendations.

In a segment on tobacco farmers in Real Lives, the National Smokers’ Alliance and Philip Morris portrayed Paul Hornbeck and his wife Pat as ordinary farmers in Kentucky to argue that tobacco control policies threaten to destroy the Hornbecks and other U.S. tobacco farmers. Paul Hornbeck says, “I've been in farming all my life. I grew up on a farm. Starting raising tobacco probably when I was ten, twelve years old with a small crop of tobacco. This farm we have here is close to average size for this area. Tobacco counts for 60% of my net income here on this farm.” Paul is pictured with a baseball cap, a long-sleeve flannel shirt and work pants, standing next to Pat who is wearing a long sleeve collar turquoise work shirt sitting on a tractor in front of tobacco seedling nurseries covered in white plastic sheeting. The subtext of video still images of the Hornbecks posed on a pick-up truck and farm workers planting seedlings shows how companies such as Philip Morris present themselves as friends of farmers to authenticate companies as legitimate community members and defenders of farmer interests.

In addition to being a farmer, Hornbeck helped Philip Morris derail the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) 1994 proposed rule to regulate tobacco products as drug delivery devices (Benowitz and Henningfield 1994). In 1995, Hornbeck was an organizer in the tobacco farm community in Kentucky and met with representatives from Jack Guthrie and Associates, the public relations firm retained by Philip Morris, “regarding distribution of material to the state's key tobacco markets and to discuss logistics of collecting petitions/letters and forwarding them to FDA prior to 1/2/96” (Jack Guthrie and Associates 1996). Tobacco companies viewed the FDA's actions a threat to their economic interests and lobbied government officials and filed a lawsuit in North Carolina in 1995 to challenge the authority of the FDA to regulate tobacco as a drug in 1998 (Borio 2002). The Philip Morris newsletter called News Line distributed to tobacco farmers and industry allies in Kentucky featured Hornbeck in a story about the threat to tobacco earnings of farmers due to a proposed 40 percent cut in tobacco farmer quotas and revenues through the national price support agreements in 1995 (Philip Morris 1995). Dan Hartlage in a summary of activities for Guthrie/Mayes Public Relations in April 1996 reported that he conducted several telephone discussions with Hornbeck “regarding implementation of communication program from tobacco-growing community targeting Congress. Discussions focused on developing tactics where farmers could have ‘face-to-face’ contact with members of Congress on issues related to tobacco” (Jack Guthrie and Associates 1996) such as proposed FDA legislation to control tobacco as a drug. In 1996, Brown and Williamson used Hornbeck in Tobacco: Working for America about tobacco's long American tradition and it economic contribution to the U.S. (Figure 8) (Brown and Williamson 1996). BAT in an October 1996 progress report of the company's Consumer and Regulatory Affairs department said that Brown and Williamson distributed Tobacco: Working for America to “smoker support groups, one of which has included this material on its internet site” (British American Tobacco 1996), and “employees, retirees, customers, state treasurers, state agricultural commissioners, chamber of commerce, tobacco industry analysts, tobacco associations, state farm bureaus, and the deans of agricultural colleges in states across the country” (British American Tobacco 1996). Hornbeck, who is described as a tobacco farmer from Shelby county Kentucky, says,

On this farm here I've got 90 acres and I raise some 15 acres of tobacco here plus I raise another 25 acres of tobacco. It's on a landlord-tenant-share scattered within a two-mile radius of this farm. This plant represents my way of life. It represents me making a farm payment at the end of the year and my family having a good Christmas, or whether we're going to college, or whatever, and paying the bills for us during the year. To the government, it amounts to some $5 per plant versus some $0.25 cents for me per plant. But if you look on a large scale, the tobacco plant means whether we farm or whether we don't farm (Brown and Williamson 1996).

Figure 8.

Tobacco: Working for America. Brown and Williamson, 1996.

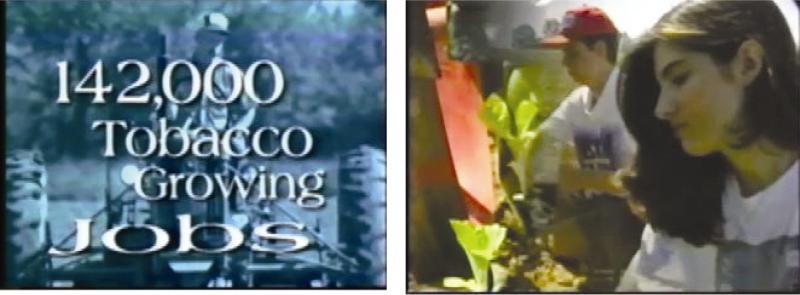

The National Smokers’ Alliance and Philip Morris (who also featured Paul Hornbeck as an ordinary farmer who would be harmed economically by government regulation of tobacco in its 1993 video Real Lives) failed to provide details that Hornbeck was a lobbyist and community organizer for Philip Morris. Brown and Williamson in Tobacco: Working for America used images of Hornbeck's family planting seedlings and Hornbeck driving a tractor overlaid with the text “142,000 Tobacco Growing Jobs” to present Brown and Williamson's position in human terms and argue that tobacco farmers and jobs would be threatened by FDA regulation.

DISCUSSION

Accurate Portrayals of the Tobacco Industry Would Include Poverty and Environmental Degradation

Tobacco industry video imagery and narratives of the social and environmental benefits of tobacco farming ignores tobacco-related poverty, child labor, political instability and deforestation in developing countries. Philip Morris, BAT and other cigarette manufacturers buy tobacco in Kenya and Guatemala (and elsewhere) that is produced by child laborers and cultivated under duress from poverty, political oppression, and environmental degradation (Stebbins 1994; Otañez, Muggli et al. 2006; Patel, Collin et al. 2007). Tobacco industry entry and the expansion of tobacco farming in developing countries contributes to poverty, economic instability, and death and disease in developing countries (Shaffer, Brenner et al. 2005; Lee 2007). In an analysis of the effects of tobacco production in the Copan Valley in Honduras, geographer William Loker concluded, “The entry of BAT-sponsored tobacco production reinforced a highly unequal social and economic system in the [Copan] valley and tied this system more tightly to national and international markets, quickening the pace of exploitation” (Loker 2004). Loker presented a counter-narrative to the narrative of the economic benefits of tobacco the tobacco industry promoted to legitimize itself and reduce threats to the smoking business.

Tobacco growing contributes to deforestation and global climate change. Curing one pound of tobacco requires 20 pounds of wood and clearing land for tobacco amounts to 500,000 acres cleared every year worldwide (Geist 1999; Esson and Leeder 2004). The 9 million acres being deforested annually for tobacco production account for nearly 5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (Farrell 2007). Replacing tobacco with food crops could feed up to twenty million of the world's current 28 million undernourished people (Farrell 2007). Tobacco's contribution to poverty, deforestation and economic instability in developing countries contradicts imagery of tobacco companies’ efforts to improve the standards of living for tobacco farmers in developing countries in Gringo Amigo and BAT in the Developing World (Table 2).

The tobacco industry imagery presents tobacco as the only viable crop in terms of hours of labor per acre, employment and earnings. In Tobacco: Seed to Pack, Philip Morris claims that tobacco requires 270 hours of labor per acre and wheat requires three and half hours of labor per acre (Philip Morris 1979). In Tobacco: Working for America, Brown and Williamson claims that the economic contribution of tobacco in 1996 includes 45 million tobacco farmers, 120,000 tobacco farm families, 2 million tobacco jobs, $22 billion in annual Federal taxes, and a $6 billion annual U.S. trade surplus derived from tobacco (Brown and Williamson 1996). Tobacco companies lobbied governments and published reports that exaggerate the economic benefits of tobacco growing (Framework Convention Alliance 2007; Otañez, Patel et al. 2007). Tobacco companies overtly and covertly funded research on tobacco crops to argue that a replacement crop for tobacco does not exist, and funded the few existing studies on alternative crops to promote the economic benefits of tobacco and counter public health arguments in support of alternative crops and livelihoods to tobacco (Framework Convention Alliance 2007; Otañez, Patel et al. 2007). In addition, tobacco companies created a climate of fear of diversification claiming that unemployment from crop substitution would increase rural to urban migration of unemployed workers and increase political instability (Framework Convention Alliance 2007; Otañez, Patel et al. 2007).

There are strong images that could be used to present an alternative narrative about tobacco farming (Figure 9). These images, from Malawi, more accurately represent reality than the images in recent tobacco industry-produced videos on the benefits of tobacco farming. The image of a shoeless child with torn clothes plucking leaves from tobacco plants reveals the tobacco harvesting tasks performed by children that prevent children from attending school. The child labor image shows the poverty pertaining to child labor of tobacco farming that is absent in industry-produced videos. The image informs viewers that tobacco companies benefit from unpaid child labor and that tobacco farming requires regulation. The image of two pesticide containers with tattered labels on dirt-covered ground depicts messages on the pesticide poisoning of farmers, agricultural chemical pollution of water tables, and depletion of soil nutrients from fertilizers and pesticides in tobacco farming. The pesticide containers, that appear to be discarded, are signs of health and environmental effects of agricultural chemical use and of tobacco as a socially damaging crop. The image of cut trees in piles next to tobacco flue-curing barns that consume wood for fuel elicits tobacco-related deforestation and destroyed land that could otherwise be used for less harmful export crops or food crops. The image of cut trees and flue-curing barns contributes to understanding of the role of tobacco companies in environmental degradation. The image offers a counter narrative to industry videos that portray companies as responsible stewards of the environment. The image of a tobacco farmer, his child, and several other farmers and children dressed in ragged clothes and shoeless sitting on dirt ground shows the human misery of tobacco growing. The weathered and stern faces of the farmers and children in the image reveal dissatisfaction with farmer indebtedness to farm landlords and tobacco companies from inflated costs for seeds and fertilizers and low tobacco prices paid by global tobacco companies. The image and narrative highlights the actual human experiences of tobacco farming and is an alternative to industry video images of tobacco companies as contributors to socioeconomic development that are intended to strengthen the industry argument about the benefits of tobacco farming.

Figure 9.

Images of the social, economic, and environmental consequences of tobacco farming in Malawi and other developing countries are strong counter messages to imagery in tobacco industry-produced videos about the benefits of tobacco farming. Photos by Martin Otañez.

Conclusion

Tobacco companies engage in the creation and circulation of visual tobacco culture to portray tobacco farming as a tradition to be protected instead of an industry to be regulated and denormalized. Images and narratives of the tobacco industry as a friend of tobacco farm families and tobacco as a driver of socio-economic development are at odds with tobacco-related child labor, deforestation, and pesticide poisoning of farmers. Tobacco companies’ partnership with American farmers portrayed in industry videos is a corporate strategy to nominally show support for farmers through loan schemes and contract arrangements while using the partnership to conceal industry influence in grower-related legislation. Tobacco industry videos contribute to visual researchers’ understanding of discourse construction and message making through videos that are unlikely to be found in photographs and text documents. Videos have been used by tobacco companies to supplement photographs, text documents, and new forms of visual data such as websites and cell phone text and photographic messages. In 2008, tobacco companies continue to use visual imagery and discursive narrative that appeal to cultural formations and values to build public faith, goodwill, and a customer base. We anticipate that tobacco companies will increase its use of videos about tobacco farming to promote claims of economic improvement in developing countries and to deflect attention away from the health and social implications of tobacco. Tobacco companies use of video imagery of tobacco farming on the Internet (British American Tobacco 2006 [inferred]) and probable use of YouTube and other free Internet social networking sites to disseminate pro-tobacco images and narratives (Freeman and Chapman 2007) suggests that health media makers need to understand and counter Internet based imagery on the economic benefits of tobacco.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a postdoctoral research grant from the American Cancer Society and a research grant (CA-87472) from the National Cancer Institute. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bazinger Tobacco depletes food-crop land. Smoke Signals. 1982;3 [Google Scholar]

- Algeo K. The rise of tobacco as a southern Appalachian staple: Madison County, North Carolina. Southeastern Geographer. 1997;37(1):46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Altheide D. Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology. 1987;10(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society Tobacco-related cancers fact sheet. 2007.

- Anderson SJ, Glantz SA, et al. Emotions for sale: cigarette advertising and women's psychosocial needs. Tobacco Control. 2005;14(2):127–35. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asila J. No cash in this crop. New Internationalist. 2004 July;369 [Google Scholar]

- Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: comparing the Minnesota Depository and internet access. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(1):68–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough S, Morrow M. A grim contradiction: The practice and consequences of corporate social responsibility by British American Tobacco in Malaysia. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1784–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin B. Invested interests: capital, culture and the World Bank. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz N, Henningfield J. Establishing a nicotine threshold for addiction- the implications for tobacco regulation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(2):123–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borio G. Tobacco timeline: the twentieth century 1950-1999- the battle is joined. 2002.

- British American Tobacco BAT in the developing world [Kenya] [videorecording] 1988.

- British American Tobacco . Consumer and Regulatory Affairs: Progress Report. British American Tobacco; Oct, 1996. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/ali34a99. [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco . News from BAT Industries. British American Tobacco; 1996. http://bat.library.ucsf.edu//tid/rni73a99. [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco Report to society. 2004 www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/BF6078CA0DD6142DC12573140052F027/$FILE/Kenya%202003-04.pdf?openelement.

- British American Tobacco Crop to consumer. 2006 [inferred] www.bat.com/group/sites/uk__3mnfen.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO76PHQU?opendocument&SKN=1&TMP=1.

- Broder S. Cigarette advertising and corporate responsibility. Jama. 1992;268(6):782–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown and Williamson The Brown and Williamson Story [videorecording] 1975 [inferred] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/glk21c00.

- Brown and Williamson Tobacco: working for America [videorecording]. 1996 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jly27a00.

- Brown and Williamson Tobacco: working for America [videorecording] 1996 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jly27a00.

- Brown and Williamson Brown and Williamson web site- tobacco processing [videorecording] 1999 [inferred] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ukk21c00.

- Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids . Golden Leaf, Barren Harvest: The Costs of Tobacco Farming. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids; Washington, D.C.: 2001. http://tobaccofreekids.org/campaign/global/FCTCreport1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Carolina Tobacco Company Carolina tobacco: roots of an ageless triumph featuring the Harley Davidson TV spot “Stuntman” [videorecording] 1995 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vnk64a00.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses- United States, 1997-2001. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacha B. Killing trees to cure tobacco: tobacco and environmental change in Kuria district, Kenya, 1969-1999; World Forestry Congress; Quebec City, Canada. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S. Tobacco and deforestation in the developing world [editorial]. Tobacco Control. 1994;3:191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S. Regulating the global vector for lung cancer. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):706–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman S, Wong WL. Tobacco control in the Third World: a resource atlas. International Organization of Consumers Unions; Penang, Malaysia: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Aid . Hooked on tobacco: British American Tobacco report. London, England: 2002. http://212.2.6.41/indepth/0201bat/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Clements E. 1968: Year of smoking and health controversy. 1968 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cyd92f00.

- Cohen JE, Ashley MJ, et al. Institutional addiction to tobacco. Tobacco Control. 1999;8(1):70–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concept Films and Tobacco Institute . Leaf: a fifteen-minute film. Brown & Williamson; 1974. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pzw93f00. [Google Scholar]

- Craig VA. Geography. Rutgers University; 2005. Restructuring tobacco livelihoods: burley growers and the federal tobacco program [dissertation]. [Google Scholar]

- Currie K, Ray L. Going up in smoke: the case of British American tobacco in Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(11):1131–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel P. Breaking the land: the transformation of cotton, tobacco, and rice cultures since 1880. University of Illinois Press; Urbana: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RM, Wakefield M, et al. The Hitchhiker's Guide to Tobacco Control: a global assessment of harms, remedies, and controversies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:171–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova N, Zhang H, et al. Applications of video-content analysis and retrieval. 2002 www-video.eecs.berkeley.edu/papers/Dimitrove/IEEE_MM2002.pdf.

- Duffin A. [Memorandum to William Kloepfer, Jr. regarding the Tiderock Corporation] Tobacco Institute; Sep 24, 1970. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jed91f00. [Google Scholar]

- Eldring L, Nakanyane S, et al. Child labor in the tobacco growing sector in Africa. 2000 www.fafo.no/pub/rapp/654/654.pdf.