Abstract

We describe a case of profound hyponatraemia in a postoperative patient after total hip replacement caused by corticosteroid insufficiency due to a non-functioning pituitary macroadenoma diagnosed by dynamic endocrine tests and radiological imaging. Adopting a multidisciplinary approach, successful diagnosis and management lead to a complete recovery without any long-term sequelae.

Keywords: Hyponatraemia, Pituitary apoplexy, Corticosteroid insufficiency

Case report

Four days after an elective total hip replacement, a previously fit and healthy 70-year-oldman complained of a headache before collapsing on the ward with a Glasgow Coma Score of 5. His blood pressure was recorded at 80/45 and his temperature was 38°C. No fit was witnessed; although his conscious level improved, he remained confused with slurred speech. His new patient finger prick capillary glucose was 4.7. A right-sided sixth cranial nerve palsy was noted causing paralysis of the lateral rectus with diplopia. His blood sodium concentration was recorded as 117 mmol/l. Treatment was instigated immediately with fluid restriction to 750 ml per 24 h and appropriate biochemical investigations were requested. A short synacthen test revealed a baseline serum cortisol level of 160 nmol/l at 09:30 (normal morning range, 450–700 nmol/l), rising to 461 nmol/l 60min after administration of 250 μM tetracosactrin. Random serum sodium osmolality was recorded as 245 mOsmol/kg (normal range, 275–295 mOsmol/kg) and urine osmolality was 417 mOsmol/kg. A chest radiograph and ECG were requested and antibiotics were commenced for basal pneumonia. Hydrocorticone (100 mg i.v.) was administered. Serum prolactin, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinising hormone (LH), testosterone, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), T3 and T4 levels were checked and urgent imaging of the pituitary fossawas arranged.Acomputed tomography scan revealed an enlargement of the sella turcica with a low density mass arising from the pituitary fossa into the supraseller cistern extending a little to the left of the mid-line with lateral extension into the cavernous sinus. The mass abutted both internal carotid vessels and the optic chiasm was significantly elevated and displaced. Appearances were suggestive of a pituitarymacro-adenoma.

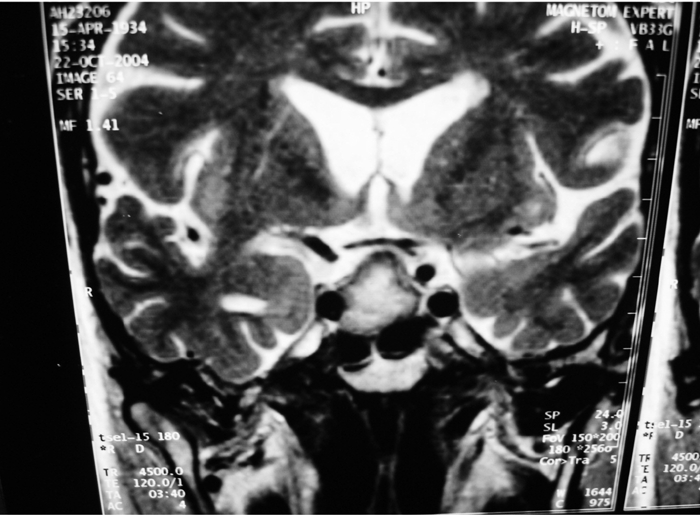

Hormone assays revealed a low FSH level at 1.5 mIU/l (normal range, 1.5-12.5 mIU/l); a low LH level at 1.6 mIU/l (normal range, 1.7–8.4 mIU/l); low TSH at 0.12 (normally, 0.3–4.5); low free T4 level 9.7 pmol/l (11–24 pmol/l); low prolactin at 25 mIU/l (normal range, 98–450 mIU/l) and a low testosterone level at 2.0 (reference range, 10–28). Formal assessment of visual fields showed superior bitemporal quandrantanopia. Gradually, over 5 days, the serum sodium level was normalised with fluid restriction and the mild cognitive impairment improved. Eight days after the initial collapse, a left-sided facial droop was noted with left inattention and slurred speech. This completely resolved within 24 h. A carotid and vertebral artery duplex scan showed only mild plaque disease. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a recent bleed into the pituitary tumour (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

T2-weighted coronal magnetic resonance images showing bleed into pituitary tumour

The patient was discharged after 2 weeks and has stabilized on hormone replacement therapy including thyroxine, hydrocorticone, monthly testosterone injections and Viagra PRN. He attends regular follow-up with the endocrinologists and has remained asymptomatic. Fortunately, he sustained no permanent brain damage from his hyponatraemic episode and the sixth cranial nerve palsy resolved. His latest MRI scan shows satisfactory tumour shrinkage; although he has been seen by the neurosurgeons, there are no plans for surgery at present.

Discussion

Hyponatraemia is the most common electrolyte disorder found in the general population and its incidence increases with age and use of thiazide diuretics.1 Over the peri-operative period, it can be aggravated by: (i) the injudicious prescription of hypotonic dextrose-containing intravenous fluids causing water overload; and (ii) the patient's normal physiological response to surgical stress causing an increased antidiuretic hormone secretion. Patients with a low plasma sodium may exhibit signs of water excess such as confusion, fits, hypertension, cardiac failure, oedema, anorexia, nausea and muscle weakness. If hyponatraemia is corrected too rapidly, a demyelinating disorder (central pontine myelinolysis) can occur, which presents with quadriplegia, dysarthria and dysphagia.

There is much in the literature regarding the dangers of hyponatraemia in the postoperative period and several papers have looked specifically at the risks for elderly orthopaedic trauma and elective patients.2,3 The orthopaedic community in particular were criticised in an editorial published in the BritishMedical Journal when they were accused of not only causing, but failing to recognize and treat appropriately, a case of hyponatraemia in a female postoperative patient after an elective total knee replacement.4 This article provoked a stream of responses and considerable debate from orthopaedic surgeons, anaesthetists, nephrologists and junior doctors.5

We describe an unusual cause of hyponatraemia in a postoperative patient after total hip replacement caused by hypo-adrenalism secondary to a non-functioning pituitary macro-adenoma. The low basal serum cortisol level which did not rise satisfactorily in response to the synacthen (an analogue of ACTH) suggested adrenocortical insufficiency as a cause for his hyponatraemia and precipitated further hormonal assays which revealed hypopituitarism. From here, imaging of the sella turcica confirmed a large tumour.

Pituitary tumours account for 10% of intracranial neoplasia and are almost always benign ademomas.1 The symptoms can be caused by local pressure effects, hormone secretion or hypopituitarism. Local pressure effects can cause headache, visual field defects (bilateral hemianopia initially of the superior quandrants), cranial nerve palsy of III, IV, VI, occasionally disturbance of temperature, sleep and feeding and, in extreme cases, erosion through the floor of the sella leading to CSF rhinorhea. The features related to hypopituitarism include amenorrhea in females, impotence in males, tiredness, anorexia, reduced libido, headache, depression, symptoms of hypothyroidism as well as postural hypotension and hyponatraemia.

If hypopituitarism is unrecognized, there is a greatly increased risk of peri-operative hypoglycaemia (reduced glucocorticoid effects of low cortisol response), hypothermia (due to hypothyroidism), water intoxication (due to ACTH deficiency and impaired ability to excrete a water load) and respiratory failure (the respiratory centre is less responsive to hypoxia and hypercarbia in hypothyroidism). If the diagnosis is known, planned replacement substitution therapy is indicated before surgery including steroid cover with hydrocortisone.

Of interest is the timing of the presentation in this case. Ten months earlier, our patient successfully recovered from the stress of a total hip replacement on the contralateral side without any detection of electrolyte disturbance. It suggests the crisis described was precipitated by the intracerebral bleed detected on MRI causing rapid expansion of the pituitary tumour leading to the sudden local pressure effects of headache with loss of consciousness – pituitary apoplexy. Since his first hip replacement, the patient commenced aspirin and clopidogrel after developing a forefoot embolism. This may have increased his risk of intracerebral haemorrhage during subsequent periods of anaesthesia. The profound hyponatraemia was caused by the glucocorticoid insufficiency and failure to excrete a water load perhaps aggravated by increased antidiuretic hormone secretion in an attempt to maintain volume in the postoperative situation.

References

- 1.Flear CTG, Gill GV, Burns J. Hyponatraemia: mechanism and management. Lancet. 1981;2:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malin JW, Kolstad K, Rothman RH. Thiazide-induced hyponatraemia in the postoperative total joint replacement patient. Orthopaedics. 1997;20:681–3. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19970801-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPherson E, Dunsmuir RA. Hyponatraemia in hip fracture patients. Scot Med J. 2002;47:115–6. doi: 10.1177/003693300204700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane N, Allen K. Hyponatraemia after orthopaedic surgery. BMJ. 1999;318:1363–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7195.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Electronic responses. Hyponatraemia after orthopaedic surgery. eBMJ. 1999;318 doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7195.1363. < www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/318/7195/1363>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]