Abstract

Sphingolipids comprise a highly diverse and complex class of molecules that serve as both structural components of cellular membranes and signaling molecules capable of eliciting apoptosis, differentiation, chemotaxis, and other responses in mammalian cells. Comprehensive or “sphingolipidomic” analyses (structure specific, quantitative analyses of all sphingolipids, or at least all members of a critical subset) are required in order to elucidate the role(s) of sphingolipids in a given biological context because so many of the sphingolipids in a biological system are inter-converted structurally and metabolically. Despite the experimental challenges posed by the diversity of sphingolipid-regulated cellular responses, the detection and quantitation of multiple sphingolipids in a single sample has been made possible by combining classical analytical separation techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with state-of-the-art tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) techniques. As part of the Lipid MAPS consortium an internal standard cocktail was developed that comprises the signaling metabolites (i.e. sphingoid bases, sphingoid base-1-phosphates, ceramides, and ceramide-1-phosphates) as well as more complex species such as mono- and di-hexosylceramides and sphingomyelin. Additionally, the number of species that can be analyzed is growing rapidly with the addition of fatty acyl Co-As, sulfatides, and other complex sphingolipids as more internal standards are becoming available. The resulting LC-MS/MS analyses are one of the most analytically rigorous technologies that can provide the necessary sensitivity, structural specificity, and quantitative precision with high-throughput for “sphingolipidomic” analyses in small sample quantities. This review summarizes historical and state-of-the-art analytical techniques used for the for the identification, structure determination, and quantitation of sphingolipids from free sphingoid bases through more complex sphingolipids such as sphingomyelins, lactosylceramides, and sulfatides including those intermediates currently considered sphingolipid “second messengers”. Also discussed are some emerging techniques and other issues remaining to be resolved for the analysis of the full sphingolipidome.

Keywords: Sphingolipids, analysis, mass spectrometry, tandem mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography, electrospray, nanospray, MALDI

1. INTRODUCTION

Sphingolipids (SLs) are 1, 3-hydroxy-2-amino alkanes or alkenes with substantial structural diversity apart from this common core moiety. SLs are structural components of cellular membranes in all eukaryotes and some prokaryotes, but their variety of signal transduction roles is also well established [1,2]. Selected SLs and a portion of their de novo biosynthetic and turnover pathways are shown in Figure 1, from which it is clear that some molecular species are free sphingoid bases (non-acylated, long-chain bases), other species are N-acylated sphingoid bases, and still other species are more complex N-acylated sphingoid bases with a polar moiety at the 1-position. While this increasing molecular diversity results from a series of biosynthetic enzymatic reactions, it should not be overlooked that reversal of these reactions (catabolism or turnover) is a commonly encountered aspect of SL metabolism. Cells exert fine-tuned control over SL metabolic flux and opposing outcomes in cellular state may hang in the balance. For example, sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate are interconverted by kinases and phosphatases [3]; the non-phosphorylated sphingoid base is pro-apoptotic [4] while the phosphorylated sphingoid base is anti-apoptotic [5]. Studies of SL biology clearly require a high degree of specificity for quantitation of multiple molecular species in a single sample because of the structural similarity and interconversion of SL species. Thus, the ability to analytically distinguish (resolve) these species is critical for the accurate determination of metabolic flux. The focus of this review is the development of state-of-the-art technologies in SL analysis, including a compilation of SL publications based upon classical analytical approaches. Although the topics are mentioned here, more comprehensive reviews of SL metabolism [6,7], metabolic inhibition, and signaling [8–11] are available.

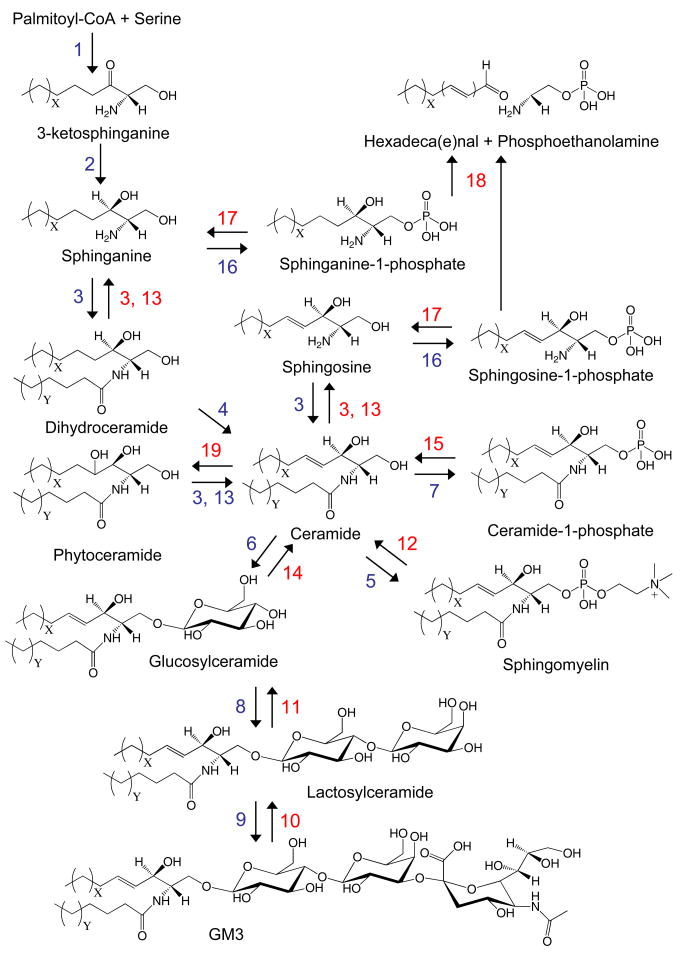

Figure 1.

A partial sphingolipid metabolic pathway with structures of selected species and numerically designated enzymatic reactions. The methylene subscript -(CH2)x- of long-chain sphingoid bases is often 13 yielding a 1, 3-dihydroxy, 18 carbon linear alkyl chain containing no sites of unsaturation (d18:0), but can range from 9 (d14:0) to greater than 17 (d22:0). The methylene subscript -(CH2)y- of the fatty acid acyl chain typically ranges from 11 (16 carbons total) to greater than 25 (30 carbons total). Enzymes of sphingolipid biosynthesis and degradation (blue and red, respectively) correspond to serine palmitoyltransferase – 1, 3-ketosphinganine reductase – 2, dihydroceramide synthases – 3, dihydroceramide desaturases – 4, sphingomyelin synthase – 5, glucosylceramide synthase - 6, ceramide kinase – 7, galactosylceramide transferase – 8, sialotransferase – 9, sialidase – 10, galactosidase – 11, sphingomyelinases (C-type) – 12, ceramidases – 13, β-glucoceramidase – 14, ceramide-1-phosphate phosphatase (putative) – 15, sphingosine/sphinganine kinases – 16, sphingosine/sphinganine-1-phosphate phosphatase – 17, sphinganine/sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase – 18, and dihydroceramide-4-hydroxylase – 19.

2. SPHINGOLIPID NOMENCLATURE

2.1. Sphingoid bases

Sphingoid bases (also called long-chain bases) include 3-ketosphinganine, sphinganine, phytosphingosine (4-hydroxysphinganine), and sphingosine (also called sphing-4-enine). The first products of de novo SL biosynthesis are 3-ketosphinganine and sphinganine. In many mammalian cell types, phytosphingosine and sphingosine are the products of phytoceramide and ceramide de-N-acylation, respectively, not direct 4-hydroxylation and 4,5-E-desaturation of sphinganine. However, yeast cells and some mammalian cell types (i.e. intestinal epithelia [12]) directly synthesize 4-hydroxy sphinganine. The number of carbon atoms in mammalian sphingoid bases is usually 18, but longer 20- and 22-carbon sphingoid bases have been detected in human skin [13], and shorter sphingoid bases, 14 carbon atoms, are prevalent in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster [14]. A systematic sphingoid base nomenclature has been proposed in which d and t designate di- and tri-hydroxylation, respectively, and two colon-delineated numbers designate the number of carbon atoms and desaturation(s) in the sphingoid base, respectively. A superscript indicates the first carbon atom of any double bond(s), thus, phytosphingosine is t18:0 and sphingosine (sphing-4-enine) is d18:1Δ4 according to this system.

Metabolites of sphingoid bases include branched chains (methyl group addition at ω-1, ω-2, and other positions), hydroxylated species at the 4- and 6-positions, 1-phosphorylated species [15], mono-, di-, and tri-N-methyl species, and N-acyl (14 to 30 or more carbon atoms) species. Double bonds of the E-configuration (trans) at the Δ4-, Δ8-, Δ4,8-, and other positions of sphinganine are the product of direct sphingoid base desaturation in yeast, but in mammals, desaturation of N-acyl sphinganine (also called dihydroceramide) is the predominant source of sphingosine-based SLs [16]. Free long chain sphingoid bases are not typically abundant, for example, sub-micromolar concentrations have been detected in human glioma cells [17], however, sphingoid base phosphates are a significant component of blood platelet membranes [18]. Cleavage of sphingoid base phosphates at the 2,3-position by sphingosine phosphate lyase eliminates the defining SL moiety, and remains the only known exit of SL from their metabolic pathway [19].

2.2. Dihydroceramide and Ceramide

The terms dihydroceramide and ceramide connote classes of N-acyl sphinganine and N-acyl sphingosine molecular species, respectively, where fatty acid alkyl chains of C16 to C24 [or greater than C30 in dermal tissues [20]] are amide linked to the amino group of the sphingoid base. This N-acyl chain variety derives from the acyl-CoA substrate specificity of six known human (dihydro)ceramide synthase isoforms [21,22], for which the systematic names CerS1 to CerS6 have been proposed. Dihydroceramide can be 4,5-E-desaturated to produce ceramide [23], or 4-hydroxylated by Δ4-dihydroceramide desaturase 1 or 2 to produce phytoceramide in mammalian cells [12]. Hydroxylation and desaturation at other positions in the ceramide portion of monohexosylceramides have also been reported [24].

Functional group addition at the 1-hydroxy position of dihydroceramide or ceramide is prevalent, and some of the most abundant SLs on a per-cell basis are modified in this way. Headgroups may be primarily linked by phosphodiester bonds at the 1-hydroxyl position yielding sphingomyelin (ceramide-1-phosphocholine, SM), ceramide phosphoethanolamine (CPE), and ceramide phosphoinositiols). Ceramide may also be 1-O modified via phosphorylation or acylation to yield ceramide-1-phosphate or 1-O-acyl ceramide, respectively, both of which interact directly with phospholipase A2 [25,26]. De-N-acylation of dihydroceramide produces sphinganine, providing an alternative to de novo biosynthesis for the generation of this sphingoid base. De-N-acylation of ceramide and phytoceramide produces sphingosine and phytosphingosine, respectively. These sphingoid bases are therefore derived from the “turnover” or “salvage” pathway, and are subject to further metabolism as described above.

2.3. Glycosphingolipids

By far the most structurally diverse sphingolipids are the glycosphingolipids (GSLs). Here a carbohydrate moiety is linked to the 1-hydroxyl position yielding a monohexosylceramide, which may be either glucosylceramide (GlcCer) or galactosylceramide (GalCer). Collectively called cerebrosides, these molecules serve as the foundations for hundreds of unique molecular structures generated by the repeated glycosylation (and deglycosylation) of a growing carbohydrate “tree” using different carbohydrate monomers (i.e. glucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, fucose, N-acetylneuraminic acid, etc.). The GSL family may be subdivided into broad classes of neutral and acidic lipids based on the absence or presence of ionizable moieties such as a carboxylic acid or sulfate, and may be further subdivided into the ganglio- (Gg), globo- (Gb), isoglobo- (iGb), lacto- (Lc), neolacto- (nLc), arthro- (At), and mollu- (Mu) series, each of which is defined by a unique tetrasaccharide core (Figure 2).

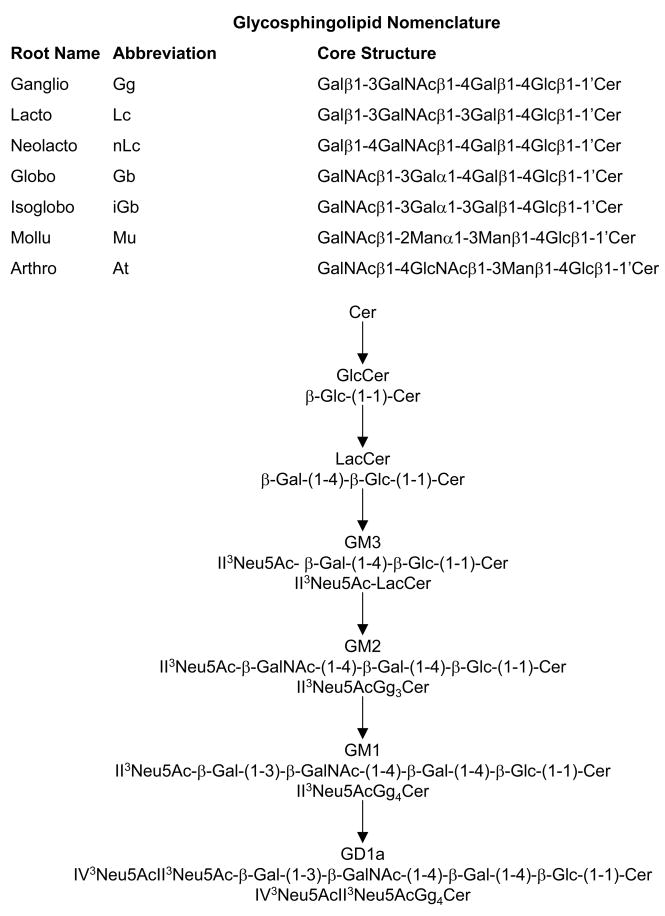

Figure 2.

Glycosphingolipid nomenclature. The core tetrasaccharide structures that define each GSL group are listed, and a portion of monosialyl ganglioside biosynthesis is shown with abbreviated nomenclature.

One nomenclature for GSL is the Svennerholm system [27] where G is used to denote ganglioside followed by the letter M, D, and T, which represents the number of sialic acid residues (mono-, di-, and tri-sialyl GSL, respectively) and ending with a number that represents the relative position of the species after resolution by thin-layer chromatography (for example the relative migrations of the GM series are GM3 > GM2 > GM1). Another more explicit nomenclature system sequentially lists saccharide subunits from the non-reducing end to the ceramide moiety, and specifies both the branching carbon atom linkage and the anomeric configurations of inter-saccharide bonds. For example, the core tetrasaccharide structure of ganglio-series GSL may be written Gal β 1-3GalNAc β 1-4Gal β 1-4Glc β 1-1′Ceramide, or simply Gg4Ceramide. Because some GSLs are isomeric (the same set of saccharide subunits but different anomeric linkages or different branching), this nomenclature system uses Roman numerals and Arabic superscripts to designate the root saccharide and its specific position(s), respectively, which are substituted, and abbreviates the core tetrasaccharide moiety. For example, GD1a may be written IV3Neu5AcII3Neu5AcGg4Ceramide and its isomer GD1aα as III6Neu5AcII3Neu5AcGg4Ceramide. As an alternative to Roman numerals and Arabic superscripts, branch saccharides may be written in parentheses after the saccharide to which they are linked. The multiple anomeric linkages between carbohydrate monomers and further carbohydrate modifications such as sulfation and acetylation increase the number of potential GSL structures beyond 10,000, indicating considerable room for discovery and characterization.

2.4. Lysosphingolipids

Other types of sphingoid base derivatives have recently garnered a great deal of attention because they have been found to be highly bioactive. These lipids include the 1-phosphates and the “lyso” sphingolipids such as lyso sphingomyelin (sphingosyl-phosphocholine) and psychosine (glucosyl/galactosyl sphingosine). Additionally, the N-methyl-derivatives (N-methylsphingosine, N, N-dimethylsphingosine, and N, N, N-trimethylsphingosine) have also been observed, however, their route of synthesis and biological function have not been fully determined.

3. CLASSICAL METHODS OF SPHINGOLIPID ANALYSIS

3.1. Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

TLC has been used for the qualitative study of sphingoid bases and their phosphates, ceramides [28], sphingomyelins [29] and more complex GSLs. Advances in high performance TLC (HPTLC) have allowed improved resolution of some molecular species [29,30]. However, TLC does not offer sufficient structural specificity to guarantee homogeneity within a single spot of lipid using detection by Rhodamine 6G or iodine vapor. This has lead to its use as a step to check fraction collections in separations of SLs followed by structural analysis by other techniques, such as boron trifluoride derivatization of fatty acids within a scraped spot followed by their TLC resolution [31,32].

3.2. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

HPLC has also been employed for separation and identification of sphingoid bases [33–35], sphingoid base 1-phosphates [36], ceramides, sphingomyelins [37], and monohexosylceramides [38]. HPLC has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive while providing resolution of SLs based on headgroup (normal phase) or N-acyl chain length (reverse phase). Detection of SLs has been primarily performed by UV or fluorescence after deacylation (for complex SLs) and modification of the free amine via addition of a chromaphore such as ortho-phthaldehyde [39]. However, recent advances in evaporative light-scattering detection (ELSD) [40] avoid any necessity for derivatization. Ceramides or other complex SL can also be analyzed either by O-benzylation derivatization using benzoyl chloride [41,42] or benzoic anhydride [43] or by examining the metabolism of synthetic derivatives (such as short chain analogues with N-[7-(4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazol] (NBD) moieties [44,45]. However, accurate quantitation often depends on definitive resolution of SL species, which HPLC alone cannot guarantee. This disadvantage exemplifies the requirement for more specific techniques of structural elucidation.

3.3. Immunochemical methodologies

Immunochemistry techniques have provided information on membrane interactions with GD3 [46], and sphingolipid recognition by anti-ceramide antibodies [47]. These methods typically employ antibody affinities for isolation of SLs for quantitation or standard protein isolations through gel electrophoresis coupled to blotting. However, it should be remembered that a high degree of specificity is not assured, and the affinity of the antibody for the desired target as well as undesired targets is possible. Certainly protein work is valuable for understanding the expression of regulatory enzymes and their precursor genes; however, these studies prove much more valuable when coupled to more rigorous quantitative analysis of the individual molecular species in the sphingolipid biosynthetic and regulatory pathways.

4. SPHINGOLIPID ANALYSIS VIA MASS SPECTROMETRY

4.1. Electron Ionization (EI) Mass Spectrometry

Electron ionization mass spectrometry was initially used to elucidate the structures of ceramides [48,49] and neutral GSL species [50,51]. These early experiments permitted the analysis of SLs as intact molecular species, and yielded diagnostic fragmentations that could distinguish isomeric SL structures [52,53]. Because these molecules were either relatively large or polar they required derivatization of the SL to trimethylsialyl or permethyl ethers to reduce their polarity and increase their volatility for efficient transfer to the gas phase. However, in some cases observation of intact higher mass molecular ions was precluded because EI induced extensive fragmentation owing to its relatively high-energy imparted during ionization. Additionally, resolution of complex mixtures of SLs with varying 1-moieties, sphingoid bases, and N-acyl combinations was particularly challenging using these methods as resulting spectra displayed numerous fragments from multiple precursors.

4.2. Fast Atom Bombardment (FAB) and Liquid Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (LSIMS)

FAB and LSIMS are ionization techniques for non-volatile lipids in which SLs are ionized off a probe tip by collisions with a beam of either accelerated atoms or ions, respectively. FAB and LSIMS ionize lipids directly without need for derivatization, and yield intact molecular ions with a lesser degree of fragmentation observed. They are therefore considered to be much “softer” ionization techniques than EI. Use of FAB or LSIMS allowed analysis of complex mixtures of monohexosylceramides [54], sphingoid bases [55] and SM [56] as individual molecular species could be distinguished by mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

Since molecular ions were primarily generated via FAB and LSIMS, structural information could also be obtained via tandem mass spectrometric analyses. Here a given precursor ion of interest would be selected by the first stage of MS, then it could be fragmented by collision-induced dissociation (CID) with a neutral gas, and resultant product ions detected by the second stage of mass analysis. When either singly protonated [M + H]+ or singly deprotonated [M − H]− precursor ions fragment, they do so at specific chemical bonds to yield product ions distinctive for the structural portions of SL: 1-position moiety, sphingoid base, and N-acyl fatty acid [57]. These pathways of fragmentation can be influenced by the inclusion of alkali metal ions as [M + Me+]+ where Me+ = Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, or Cs+ [58].

FAB and LSIMS have some limitations for SL analysis. Both of these methods require a non-volatile, protic matrix to solubilize the analyte of interest and aid in its ionization. These matrices also become ionized and give rise to a significant amount of background chemical noise, which can limit sensitivity, especially for lower molecular mass species, such as the free sphingoid bases and their phosphates. Methods such as dynamic FAB [59,60] partially addressed this problem by continuous infusion of a dilute solution of the matrix to the probe tip. However, the ~ 100-fold reduction in background noise was not enough to completely eliminate background chemical noise from matrix at low analyte concentrations.

4.3. Electrospray Ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry

ESI allows SLs in solution to be continuously infused directly into the ion source of a mass spectrometer. The central component of this ion source is a hollow metal needle, which is held at a high positive or negative potential. At the exit tip of the needle highly charged solvent droplets containing SLs are formed and are subsequently drawn into the orifice of a mass spectrometer via both a potential and atmospheric pressure difference. During transition from atmosphere to high vacuum, the charged droplets shrink as neutral solvent molecules are pumped away. Eventually the charge on the surface of the droplet exceeds the forces holding it together, and it undergoes a coulomb explosion creating new smaller charged droplets. This process continues repeatedly until the analyte of interest reaches the surface and becomes ionized in the gas phase. This ionization technique results in a much softer ionization, and when optimized yields primarily intact molecular ions with little or no fragmentation.

Early ESI ion sources required low flow rates (1–10 uL/min) and multiple pumping stages to remove excess solvent. However, ESI provided greatly reduced chemical noise and yielded sensitivity orders of magnitude lower than either FAB or LSIMS. More recently ESI sources have been developed to handle either very low or very high flow rates. The low flow rate regime of 10–500 nL/min is known as nanospray, and provides greatly enhanced sensitivity. The high flow rate regime can now easily handle flow rates of several mL/min using heated gas flow to nebulize solvent flow for high throughput sample processing. As with the other soft ionization techniques, structural information could likewise be obtained via MS/MS, allowing specific 1-position moiety, sphingoid base, and fatty acid combinations to be determined.

4.4. High Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry and Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The ESI method of direct sample introduction and ionization via solution naturally lends itself to coupling HPLC prior to mass spectrometric analysis for added separation and analytical robustness for quantitation. When analyzed in this manner SLs may be de-salted, chromatographically focused, and selectively eluted, all of which enhance sensitivity. HPLC also serves to reduce the complexity of the eluent at any given elution time, which greatly reduces ionization suppression effects from other species further improving quantitative accuracy and sensitivity. Additionally, HPLC allows the separation of isomeric and isobaric species, which are indistinguishable by mass spectrometry alone.

HPLC-MS/MS has been used to identify, quantify, and determine the structures of free sphingoid bases, free sphingoid base phosphates, ceramides, monohexosylceramides (both GalCer and GlcCer), lactosylceramides (LacCer), SM [61,62] and more complex GSLs [63,64]. Complete chromatographic resolution of all individual species within a given class of SLs is not required in LC-MS/MS as long as non-chromatographically resolved species have unique precursor ion-product ion m/z values. Here the unique combination of an individual molecular species precursor ion m/z value and structure specific product ion (for example, all of the N-acyl chain length variants of LacCer) allows the mass spectrometer to differentiate between many components present in a complex mixture even if they co-elute during LC. The inclusion of an appropriate internal standard that co-elutes with analytes allows normalization reflecting any ionization suppression/enhancement occurring during that LC elution time. However, species with identical precursor ion-product ion m/z values (such as GlcCer and GalCer) must be baseline resolved by LC for accurate quantitation.

Separations of sphingolipids via HPLC have mainly been distributed between two types of HPLC: reversed phase LC [65–67] for separations based on the length and saturation of N-acyl chain (for example, to separate sphingosine and sphinganine) and normal phase LC [65,68,69] to separate compounds primarily by their 1-position moiety constituents (for example, resolving ceramide, hexosylceramide, dihexosylceramide, and SM from each other and from other lipids, etc.). The requirement for some LC separations may not be immediately realized. For example, sphingosine and sphinganine have easily resolved precursor and product ion m/z values. However, typically in biological samples sphingosine is much more abundant than sphinganine, and the naturally occurring [M + 2] isotope of sphingosine (~ 2.0% natural isotopic abundance) will have the same precursor and product ion m/z as sphinganine. It will therefore interfere with the quantitation of sphinganine unless the sphingoid bases have been separated by LC [65]. Although it is simple to calculate the mass isotopomer distribution of a particular analyte based on its molecular formula and correct (by subtraction) any contribution that non-monoisotopic isotopomers are making to higher m/z analytes, on triple quadrupole instruments this approach requires a nominal m/z difference of at least 1 Da between the analytes and is therefore not applicable to isobaric (and non-resolved by LC) analytes such as GlcCer and GalCer as well as several other isomeric species.

4.5. Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization (MALDI) Mass Spectrometry and Tandem Mass Spectrometry

MALDI has been used to identify several different classes of SLs including ceramide, monohexosylceramide, and SM [70] as well as complex GSLs, including LacCer, globosides [71], and gangliosides. Samples are often prepared for MALDI by mixing a solution containing the analyte with a solution containing a matrix compound that is usually at a much higher concentration than the analyte. MALDI matrices are typically small substituted organic acids that contain a moiety that can absorb the photonic energy of the laser. Absorption of the laser energy causes the matrix to become vibrationally excited and volatilize taking matrix molecules, ions, and analyte molecules with it into the gas-phase. Here the analyte, matrix molecules, and ions under go charge exchange reactions resulting in the analyte becoming ionized. These may then be accelerated out of the source for subsequent mass analysis. Matrix choice is critical to successful generation of intact molecular species with regard to minimal fragmentation, maximum sensitivity, and has been thoroughly reviewed [72].

MALDI ion sources are typically used in conjunction with time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzers because the laser pulse and resulting ion plume provides a discreet event that is compatible with TOF mass analysis. Because of the nature of MALDI ionization, studies of more complex GSLs have often utilized this technique. MALDI efficiently produces primarily singly charged ions, which in conjunction with the high m/z range of TOF instruments, has aided in the observation of higher molecular weight GSLs. One disadvantage of this ionization technique is that many matrices produce abundant background chemical noise at lower m/z values, which precludes analysis of smaller free sphingoid bases and similarly sized SLs. However, new advances in matrix choices, high pressure ion sources, and MS/MS may provide an opportunity to study these lower molecular weight SLs by MALDI.

5. EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES FOR SPHINGOLIPIDOMIC ANALYSES

The term “sphingolipidomic” analysis refers to the structure specific and quantitative measurement of all the individual molecular species of sphingolipids so that the role of each in a given biological context (i.e. biosynthesis or turnover) may be determined. To this end, LC-MS/MS is currently the analytical tool of choice for “sphingolipidomic” analyses for several important reasons. First, LC-MS/MS provides three orthogonal points of specificity with regard to differentiation of complex molecular species: retention time, molecular mass, and structure. This is especially true when used in conjunction with high resolution and accurate mass measurement, which yields empirical formula of both precursor and product ions. Second, LC-MS/MS provides levels of sensitivity that are orders of magnitude lower than those of classical techniques. This enables detection of SLs present in minute quantities (~ fmol or less) in small sample amounts (~106 cells). Third, the signal response of SLs analyzed by LC-MS/MS can be correlated to their concentration yielding quantitative information. (It should be noted that accurate and precise quantitation via MS requires use of appropriate internal standards to control for sample losses in extraction, and normalization for differences in ionization and fragmentation of various individual molecular species.) Fourth, liquid chromatography is essential for separation of complex mixtures of sphingolipids. This is because interferences from other molecules having the same mass (isobaric) or similar structures (galactose vs. glucose 1-position moieties) can yield erroneous quantitative results. Finally, LC-MS/MS provides a wide dynamic range, typically several orders of magnitude for quantitation of SLs. This allows analysis of SLs that vary in abundance over this range in biological systems (ie. SM versus sphingosine-1-phosphate). In spite of all these positive attributes, poor choices in analytical techniques and experimental design can yield erroneous results. Critical steps during quantitation include sample handling and extraction protocols, separation of isomeric and isobaric species prior to mass analysis, internal standards, ionization technique, instrument choice (mass analyzer, interface, and tuning), and MS or MS/MS analysis technique. Serious errors at any of these steps will result in compromised data that is not adequate for quantitation, and this experimental complexity is a potential disadvantage of LC-MS/MS of SL.

Useful “sphingolipidomic” data generated via MS depends fundamentally on the gas-phase chemistry of the molecules of interest. They must readily form abundant intact precursor and subsequent product ions, which will serve as unique and sensitive identifiers of each individual molecular species. Fortunately, SLs have been demonstrated to be highly amenable to analyses via MS as they are readily ionized, and many fragment to produce abundant and distinctive product ions that are indicative of the headgroup, sphingoid base, or fatty acid moieties. In the positive ion mode both the free long chain sphingoid bases and complex sphingolipids ionize readily via ESI to form (M + H)+ ions. Alternatively, when ionized in the negative ion mode, anionic SLs form abundant molecular ions, such as [M − H]− sphingoid base-1-phosphates, [M − H]− ceramide-1-phosphates, [M − 15]− SM (loss of one methyl group), [M − H]− sulfatides, and [M − nH]n− gangliosides. However, when some sphingolipids fragment and the charge site is located on the 1-position moiety rather than on the ceramide moiety, such as with SM, only the total number of carbon atoms and unsaturations can be determined. No direct information about the composition of the sphingoid base or fatty acid can be elucidated, unless alternative techniques, such as negative mode analysis or multiple stages of tandem mass spectrometry (MSn) are employed.

Sphingolipidomic analyses are important because they reveal changes in the pathways of metabolic flux of SLs from either biosynthesis or turnover in a biological system. For example, a family of genes has recently been linked to the biosynthesis of ceramides and dihydroceramides in mammalian cells, and different gene products preferentially utilize different fatty acyl-CoA substrates [21,73–75]. One of these (dihydro) ceramide synthase (CerS) enzymes (formerly named LASS-1) was identified as a mammalian homolog of the yeast Longevity Assurance Gene 1 (LAG-1) [73]. Detailed analysis of the full spectrum of N-acyl chain lengths of ceramides and monohexosylceramides in HEK-293T cells transiently over-expressing LASS1 revealed an increase in C18:0 N-acyl chain species, and this increase also showed resistance to inhibition by fumonisin B1 (FB1), a known inhibitor of CerS [76]. While radiolabeling experiments were also performed, the structure-specific data from LC-MS/MS analysis provided the necessary specificity to demonstrate the chain length preference of CerS1 for the stearoyl-CoA substrate.

CerS4 and CerS5 (formerly LASS4 and LASS5) also have demonstrated fatty acyl-CoA substrate preference during biosynthesis of dihydroceramides [21]. Analysis of complex SL N-acyl chain lengths in HEK-293T cells transiently over-expressing CerS4 or CerS5 included ceramides, monohexosylceramides, SM, and their dihydro- counterparts. CerS5 over-expression increased synthesis of C16:0 dihydroceramides, while CerS4 over-expression resulted in a less pronounced increase in C18:0 and C20:0 species. Also in both cases, the over-expression of a CerS family protein conferred FB1 resistance for biosynthesis of that particular chain length (see the CerS1 over-expression results above). The changes in dihydroceramide N-acyl profile in both cases were shown to consequently alter N-acyl profiles of monohexosylceramides and SM and their corresponding dihydro species. This work clearly demonstrated CerS5 to be an actual DHCerS [22]. Additionally, hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged CerS5 was immuno-purified and assayed for activity with palmitoyl-CoA and stearoyl-CoA. The purified CerS5 was shown to have a higher preference for palmitoyl-CoA. Thus, combinatory studies between “sphingolipidomics” and more traditional biochemical methodologies were able to identify a family of genes through homology, characterize the sphingolipids they influenced, determine their susceptibility to an inhibitor, and give direction to enzymatic classification.

6. INNOVATIONS AND NEW APPLICATIONS IN THE MASS SPECTROMETRIC ANALYSIS OF SPHINGOLIPIDS

6.1. “Shotgun” lipidomics

Other mass spectrometric techniques have been introduced for the identification, structure determination, and quantitation of sphingolipids. For example, two-dimensional (2D) ESI MS, using a triple quadrupole instrument has been described by Han and Gross [77,78]. This technique utilizes MS and MS/MS analyses of an infused sample in both positive and negative ESI conditions. The formation of charged molecular adducts in the positive mode and anionic species in the negative mode is promoted by the presence of aqueous LiOH and/or LiCl. These techniques are advantageous because they are a relatively simple and rapid way to profile numerous classes of SLs and glycerol lipids in a crude lipid extracts. However, it should be noted that the disadvantages such as the possibility of ionization suppression and the inability to distinguish isomeric and isobaric species are significant.

The 2D technique involves acquiring an MS scan over an m/z range encompassing the lipids of interest using the first quadrupole, with the instrument in positive ion mode when analyzing cationic lipids and Li+ adducts, and in negative ion mode when analyzing anionic lipids and Cl− adducts. The resulting mass spectra contain some peaks representing a single molecular species, but also contain some peaks representing the sum of isobaric lipids that cannot be directly resolved and quantitated by a single stage of mass analysis even in the presence of internal standards. However, the lipid classes and their individual molecular species may be differentiated by precursor ion scans and/or neutral loss scans that can indicate structural components of the molecules of interest. These signature fragmentations of a particular lipid class or species have been used to distinguish phosphatidlycholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositols (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS), diacyl- and triacylglycerols (DAG/TAG), cardiolipin, free fatty acids, phosphatidic acid, as well as sphingolipids such as ceramides, cerebrosides, and SM in diluted chloroform extracts of mouse livers [78]. Although the calculation of isotopomer abundance can be used to correct the “spillover” of an analyte to higher m/z values (see above), the inability to distinguish the relative abundances of isobaric (but isomerically distinct) species within a single mass spectrum peak is a limitation of non-LC methods.

6.2. Nanospray and high-resolution mass spectrometry

The use of nanospray in conjunction with high resolution MS and MS/MS analyses via quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometers has been shown to be an innovative extension of the 2D lipid profiling technique [79]. In this method very small volumes of sample are infused into the mass spectrometer for extended periods of time via a chip containing a high-density array of nanospray nozzles. This allows numerous product ion analyses to be performed incrementally across a desired mass range. The resulting product ion data is then queried for structure specific fragment ions or neutral losses corresponding to unique lipid fragment ions or neutral losses similar to the triple quadrupole approach. The resulting output yields the individual 1-position moiety, fatty acid, and sphingoid base combinations of the various intact lipid species present in the sample. Furthermore, the high resolution and mass accuracy of the TOF mass analyzer allows a much smaller product ion selection window to be used versus a quadrupole mass analyzer. This results in a reduction of the detection of spurious peaks not associated with the lipids of interest.

The advent of chip-based nanospray techniques [80–82] provides several unique advantages over other profiling techniques. Since flow rates are on the order nL/min, very little sample is consumed and background chemical noise is greatly reduced. This serves to enhance overall sensitivity and minor lipid species are more readily detected. The chip-based nanospray systems contain a high-density array of nanospray nozzles that are robust and reproducible enabling analyses from highly organic solvents and automated analyses for increased throughput. Additionally, samples can be analyzed discreetly (one sample and tip per spray nozzle) removing the possibility of sample carry-over and cross contamination when comparing different samples.

It should be noted that all infusion-based techniques have limitations with regard to unambiguous identification and more importantly quantitation of sphingolipids. In several cases these methods cannot differentiate highly important isomeric or isobaric species precluding their quantitation. Sphingolipid quantitation via these methods is questionable for several reasons. First, these methods are highly susceptible to ionization suppression/enhancement. This is a direct result of the sample consisting of a complex mixture of analytes having widely varied concentrations and each class of lipid species having much different gas-phase basicity or acidity. Therefore, a change in a single component in the sample can greatly affect the relative abundances of numerous other species in the sample. Second, infusion based methods using MS/MS are affected by isotopic interferences. Here an isotope of one species may occur at the same nominal m/z as another species, and if the two species possess some structural similarities (ie. fatty acid, 1-position moiety, etc.), a false or inflated signal will result demonstrating the need for an orthogonal means of separation. While relatively simple calculations can be done to predict “isotopic spillover” of a sample component to higher m/z values, these calculations are not useful until the presence and identity of the sample component(s) are known. Third, the rate of dissociation of ions (kinetics) not only varies between classes of lipid species, but also with the chain length [83,84], hydroxylation [83], and unsaturation [83,84] within a given class. Therefore, at one collision energy a given set of ions may yield one set of relative abundances, but with another collision energy the relative abundances would be quite different. A final point of consideration is that those methods that utilize TOF mass analyzers typically have micro channel plate detectors. These detectors yield high sensitivity and temporal resolution, but have a very limited dynamic range, typically only slightly more than 2 orders of magnitude. Thus, quantitative information regarding specific molecular species using these techniques is narrowly constrained.

Newer chip-based nanospray systems can address some of these issues by enabling HPLC column coupling directly to the chip as well as simultaneous fraction collection of excess eluent. When used in this manner complex mixtures can be separated and analytes selectively eluted under conditions where ionization suppression effects are minimized. Similarly, isotopic, isomeric and isobaric effects can be differentiated. The resulting LC-MS or LC-MS/MS data may then be used for quantitation when the kinetic and dynamic range issues are addressed and the appropriate internal standards are included. Furthermore, additional more detailed structural information may be obtained by analyzing a particular fraction containing an analyte of interest in greater detail (i.e. MSn).

6.3. Ultra high-resolution mass spectrometry

Ultra high-resolution and accurate mass measurement also hold promise for a more comprehensive elucidation of the sphingolipidome. Both nanoESI [85,86] and MALDI [87,88] have been used to ionize SLs for subsequent analysis via Fourier transform mass spectrometry (FTMS). The former methods have been primarily focused on the identification and structure determination of glycosphingolipids. In this work some interesting new alternative fragmentation techniques for lipids such as infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD), electron capture dissociation (ECD), and electron detachment dissociation were used providing observation of additional fragment ions [85]. The latter technique has been used to analyze glycolipids directly from TLC plates [88], and profile lipid species present in intact cells [89], and plant tissues [90]. The use of ultra high resolution and accurate mass measurement has been shown to be able to group various classes of phospholipids [89], and uniquely identify lipid or carbohydrate fragment ions using mass defect plots [85].

Unambiguous differentiation of isomeric species such as the glycosphingolipids Glc/GalCer, for subsequent identification and/or quantitation can currently only be done via use of liquid chromatography. The advent of alternative separation techniques such as ion mobility mass spectrometry offers additional possibilities to address separation of lipids [91]. Here ions of the same m/z are separated based on differences in their mobility through a buffer gas in an applied electric field [92]. The time required for a given ion to traverse the length of the field is directly affected by its three-dimensional shape. Therefore, ions with a greater cross section (more expansive) migrate more slowly than do more compact ions [92]. Thus, it is theoretically possible to distinguish between different isomers or conformations of ions having the same m/z [93,94].

6.4. Imaging mass spectrometry

The impetus for sphingolipidomic analyses has been to identify and quantify all lipids so that an understanding of how they are interconverted from one species to another results in a biological response. Unfortunately, almost all the techniques used to identify and quantify sphingolipids involve their extraction and removal from their biological, topological, and sub-cellular environment resulting in a loss of this information. Direct tissue analysis and imaging mass spectrometry are emerging technologies that have promise to address these questions not answered by the analytical techniques mentioned previously.

Briefly, the SIMS technique utilizes a tightly focused beam of primary ions to impinge on the surface of the biological material generating a secondary stream of ions from it. This is contrasted by MALDI in which the surface of a sample is coated with a matrix which serves to absorb the laser light, then volatilize and ionize the sample as described earlier. The SIMS technique provides greater spatial resolution owing to a more tightly focused high-energy beam. However, this high-energy ion beam causes extensive fragmentation of molecular species sputtered from the surface, precluding identification of intact molecular species. This is contrasted by MALDI, which has a lower spatial resolution because of the larger laser spot size, but can generate intact molecular ions. In both techniques the ionization beam is incrementally moved across the surface of interest generating discrete mass spectra for a given location. Specific m/z values may then be plotted in x, y-space, and different colors assigned to each distinct m/z value of interest to yield a molecular image of the biological sample. Thus, specific molecular species may be assigned to discrete regions in the sample. Significant challenges to both techniques such as the requirement of analysis under high vacuum, interpretation of large data sets, and ionization suppression still remain.

Both the MALDI and SIMS TOF techniques have been recently used to directly analyze tissues [95,96] and cells [97] for their lipid content and localization. Brain slices directly probed via MALDI revealed that the primary sphingolipids observed were SM, sulfatides, and gangliosides [95]. Interestingly, some differential localization was observed such that cerebellar cortex contained small amounts of SM/sulfatide, and larger amounts of the gangliosides GM1, GD1, and GT1. This is contrasted by cerebellar peduncle that contained much higher levels of ST and primarily ganglioside GM1 with smaller quantities of GD1. Similarly, brain slices probed by SIMS TOF revealed that chain length variants of GalCer were differentially localized in white matter [96]. Here it was observed that C18 GalCer was localized in cholesterol regions and C24 GalCer was primarily found in Na/K-enriched areas [96].

7. SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVE

Initially described and named in 1884 by Jo-han Ludwig Wilhelm Thudichum [98], sphingolipids are now known to mediate many important cellular processes, such as apoptosis, differentiation, and chemotaxis. The structural diversity of SLs has been established by numerous chromatographic separation techniques, including TLC and HPLC. Mass spectrometry provides many advantages in the detection of SLs, especially sensitivity, and both specificity and structural information may be provided by MS/MS scans. An additional advantage of MS and MS/MS is the ability to detect or quantitate multiple analytes in a single sample, because the extensive metabolic interconversion of SLs necessitates multi-component analysis. Resolution with TLC or HPLC before MS and MS/MS analysis provides an additional criterion (relative mobility or retention time) for identification, but also allows distinction of isobaric and isomeric species while reducing ionization suppression, which may dramatically effect subsequent quantitation.

In spite of the last century’s advances in the detection, structural elucidation, and quantitation of SLs, important challenges remain unsolved. The numerous roles of GSLs, the most structurally elaborate sphingolipids, are being uncovered by many groups. The subcellular localization and distribution of SLs are beginning to be probed directly by SIMS and imaging MALDI TOF. Stable isotopes are being used to trace SL metabolic flux, and at least one mathematical model of this flux has also been developed [99]. Connections between SL and non-SL signal transduction cascades are being reported. However, the location, timing, and regulation of changes in SL metabolic flux (the status of the sphingolipidome) remain among the most difficult fields of study wherein the analytical tools described by this review are indispensable and a selected portion of this legacy knowledge is summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Selected techniques used for the analysis of sphingolipids.

| ESI | MALDI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLC/HPTLC | HPLC | EI | FAB-MS & MS/MS | MS | MS/MS | MS | MS/MS | ||

| Sphingoid bases | [18,22, 100–103] | [14,33–36, 39,40,65, 104–110] | [48,103, 110] | [55, 111–117] | [14,65, 109, 118–120] | [17,65, 108,109, 118–121] | |||

| Sphingoid base phosphates | [122–125] | [36,40,65, 107,124] | [111, 115,117] | [17,65,119, 121,126–128] | |||||

| Ceramide | [28, 129–135] | [41,45,65, 107,109, 136–138] | [48,139, 140] | [113, 141,142] | [17,65,109, 119–121] | [143–145] | |||

| Sphingomyelin | [55,125,129, 133,146–154] | [37,65,68, 107,150, 155–163] | [152] | [113, 164,165] | [14,17,65, 68,119,121, 162,163, 166,167] | [154,168–171] | |||

| Ceramide phosphoethanolamines | [172,173] | [173,174] | [172,173] | [172] | |||||

| Lyso- sphingolipids | Ceramide phosphate | [125,175–177] | [172] | [116] | [115,117] | [126] | |||

| Psychosine | [135,137, 178–180] | [33,137, 181,182] | [183] | [184] | [185] | ||||

| Sphingosyl- phosphocholine | [124,145, 186,187] | [33,124, 186–188] | [55, 186,189] | [107,127] | [124,145,188] | ||||

| Neutral glyco- sphingolipids | Glucosyl- ceramide | [116,125, 174,178, 190–192] | [38,60,65, 193–198] | [51,54, 116,191, 196,197] | [59,60, 141,191] | [120, 167,199] | [17,65,118, 120,121, 167,199] | [70,143] | |

| Galactosyl- ceramide | [137,178, 200] | [42,65, 109,194] | [53,201] | [141, 142,201] | [109, 199,202] | [65,109, 118,199] | [200,203] | [204] | |

| Lactosyl- ceramide | [192, 205–207] | [65,66, 160,193,194, 197,198] | [208,209] | [141, 142,210] | [66,167] | [65,66, 118,167] | [211] | [211] | |

| Lacto series | [28,212,213] | [213–215] | [216] | ||||||

| Globo series | [135,178, 192,205] | [41,193, 197,198, 217–219] | [51,209, 216, 220–222] | [60,141, 216,219, 223–225] | [167,226] | [60,167, 227,228] | [145,191,211] | [145, 211] | |

| NeoLacto series | [212,229–231] | [232] | [216,223,225,233] | [232] | [232,234] | ||||

| Acidic glyco- sphingolipids | Gangliosides | [29,30, 192,207, 235–241] | [59,109,197, 207,214, 242–252] | [51,209, 213,216,222, 239, 253–256] |

[59,207,216,223–225,238,240, 252,253,255,257–265] |

[109, 167,266] | [109,167, 266–268] | [203,269,270] | |

| Sulfo- glycosphingolipid | [29,129,135, 190,271–273] | [109,197, 274–276] | [225,254] | [109, 167,277] | [109,167, 277] | [185,202,278–280] | |||

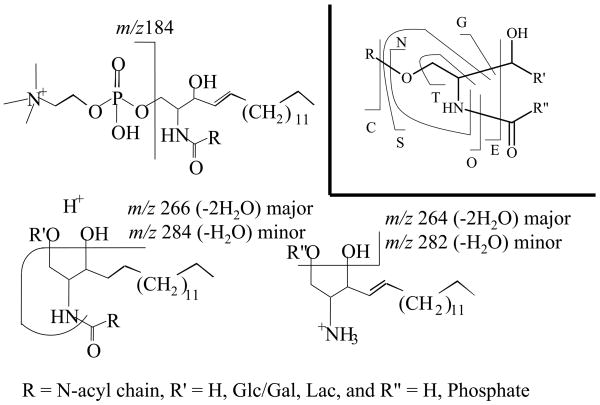

Figure 3.

Fragmentation of sphingolipids observed in the positive ion mode. Fragmentation of long-chain bases, long-chain base phosphates, ceramides and monohexosylceramides involves dehydration at the 3-position, dehydration at the 1-position or cleavage of the 1-position moiety with charge retention on the sphingoid base. Sphingomyelin similarly cleaves at the 1-position, however the charge is retained on the phosphorylcholine headgroup yielding the m/z 184 ion.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Alfred H. Merrill, Jr. for critical reading of this manuscript and Lipid MAPS (U54 GM069338) for continued support.

Abbreviations

- SLs

sphingolipids

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- SM

sphingomyelin

- CPE

ceramide phosphoethanolamine

- GSLs

glycosphingolipids

- GlcCer

glucosylceramide

- GalCer

galactosylceramide

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- EI

electron ionization

- FAB

fast atom bombardment

- LSIMS

liquid secondary ion mass spectrometry

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- m/z

mass-to-charge ratio

- [M + H]+

singly protonated molecule

- [M −H]−

singly deprotonated molecule

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- LC

liquid chromatography

- LacCer

lactosylceramide

- MALDI

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization

- TOF

time-of-flight

- SIMS

secondary ion mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Buccoliero R, Futerman AH. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:409. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel S, Merrill AH., Jr Faseb J. 1996;10:1388. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.12.8903509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Stunff H, Galve-Roperh I, Peterson C, Milstien S, Spiegel S. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung WC, Chang HC, Chuang LY. Biochem J. 1999;338(Pt 1):161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osawa Y, Banno Y, Nagaki M, Brenner DA, Naiki T, Nozawa Y, Nakashima S, Moriwaki H. J Immunol. 2001;167:173. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Echten-Deckert G, Herget T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hannun YA, Luberto C, Argraves KM. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4893. doi: 10.1021/bi002836k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menaldino DS, Bushnev A, Sun A, Liotta DC, Symolon H, Desai K, Dillehay DL, Peng Q, Wang E, Allegood J, Trotman-Pruett S, Sullards MC, Merrill AH., Jr Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:373. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalfant CE, Spiegel S. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4605. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futerman AH, Hannun YA. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:777. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnino S, Prinetti A, Mauri L, Chigorno V, Tettamanti G. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2111. doi: 10.1021/cr0100446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omae F, Miyazaki M, Enomoto A, Suzuki M, Suzuki Y, Suzuki A. Biochem J. 2004;379:687. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart HJ, Rougon G, Dong Z, Dean C, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Glia. 1995;15:419. doi: 10.1002/glia.440150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fyrst H, Herr DR, Harris GL, Saba JD. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:54. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300005-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maceyka M, Sankala H, Hait NC, Le Stunff H, Liu H, Toman R, Collier C, Zhang M, Satin LS, Merrill AH, Jr, Milstien S, Spiegel S. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ternes P, Franke S, Zahringer U, Sperling P, Heinz E. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullards MC, Wang E, Peng Q, Merrill AH., Jr Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2003;49:789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tani M, Sano T, Ito M, Igarashi Y. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2458. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500268-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiss U, Oskouian B, Zhou J, Gupta V, Sooriyakumaran P, Kelly S, Wang E, Merrill AH, Jr, Saba JD. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farwanah H, Wohlrab J, Neubert RH, Raith K. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383:632. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riebeling C, Allegood JC, Wang E, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahiri S, Futerman AH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel C, van Echten-Deckert G, Rother J, Sandhoff K, Wang E, Merrill AH., Jr J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullards MC, Lynch DV, Merrill AH, Jr, Adams J. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(200003)35:3<347::AID-JMS941>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettus BJ, Bielawska A, Subramanian P, Wijesinghe DS, Maceyka M, Leslie CC, Evans JH, Freiberg J, Roddy P, Hannun YA, Chalfant CE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abe A, Shayman JA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svennerholm L. J Lipid Res. 1964;5:145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack JD, Clark DS, Somerson NL. J Lipid Res. 1971;12:563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollet S, Ermidou S, Le Saux F, Monge M, Baumann N. J Lipid Res. 1978;19:916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban PF, Harth S, Freysz L, Dreyfus H. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;125:149. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-7844-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledeen R, Salsman K, Cabrera M. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rokukawa C, Kushi Y, Ueno K, Handa S. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1982;92:1481. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jungalwala FB, Evans JE, Bremer E, McCluer RH. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura K, Nakamura A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1985;98:1247. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shephard GS, van der Westhuizen L. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1998;710:219. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lester RL, Dickson RC. Anal Biochem. 2001;298:283. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith M, Monchamp P, Jungalwala FB. J Lipid Res. 1981;22:714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki A, Handa S, Yamakawa T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1976;80:1181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caligan TB, Peters K, Ou J, Wang E, Saba J, Merrill AH., Jr Anal Biochem. 2000;281:36. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McNabb TJ, Cremesti AE, Brown PR, Fischl AS. Anal Biochem. 1999;276:242. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki T, Suzuki A, Handa S, Yamakawa T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1979;86:803. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCluer EH, Evans JE. J Lipid Res. 1976;17:412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCluer RH, Evans JE. J Lipid Res. 1973;14:611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipsky NG, Pagano RE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.9.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin OC, Pagano RE. Anal Biochem. 1986;159:101. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prinetti A, Prioni S, Chigorno V, Karagogeos D, Tettamanti G, Sonnino S. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1162. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowart LA, Szulc Z, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:2042. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200241-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samuelsson B, Samuelsson K. J Lipid Res. 1969;10:41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuelsson B, Samuelsson K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968;164:421. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(68)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuelsson K, Samuelsson B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969;37:15. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sweeley CC, Dawson G. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969;37:6. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hammarstrom S, Samuelsson B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;41:1027. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samuelsson K, Sameulsson B. Chem Phys Lipids. 1970;5:44. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(70)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamanaka S, Asagami C, Suzuki M, Inagaki F, Suzuki A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1989;105:684. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hara A, Taketomi T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1983;94:1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi A, Matsubara T, Morita M, Kinoshita T, Nakamura T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1989;106:264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeanette Adams QA. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 1993;12:51. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qinghong Ann JA. Analytical Chemistry. 1992;65:7. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki M, Yamakawa T, Suzuki A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1990;108:92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suzuki M, Sekine M, Yamakawa T, Suzuki A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1989;105:829. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullards MC, Merrill AH., Jr Sci STKE. 2001;2001:pl1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.67.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pettus BJ, Bielawska A, Kroesen BJ, Moeller PD, Szulc ZM, Hannun YA, Busman M. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:1203. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kushi Y, Rokukawa C, Numajir Y, Kato Y, Handa S. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:405. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki M, Yamakawa T, Suzuki A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1991;109:503. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Merrill AH, Jr, Sullards MC, Allegood JC, Kelly S, Wang E. Methods. 2005;36:207. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaga N, Kazuno S, Taka H, Iwabuchi K, Murayama K. Anal Biochem. 2005;337:316. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee MH, Lee GH, Yoo JS. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:64. doi: 10.1002/rcm.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pacetti D, Boselli E, Hulan HW, Frega NG. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1097:66. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pettus BJ, Kroesen BJ, Szulc ZM, Bielawska A, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Busman M. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:577. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujiwaki T, Yamaguchi S, Sukegawa K, Taketomi T. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1999;731:45. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(99)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suzuki Y, Suzuki M, Ito E, Goto-Inoue N, Miseki K. Journal of Biochemistry. 2006 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.David JH. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2006;25:595. doi: 10.1002/mas.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Venkataraman K, Riebeling C, Bodennec J, Riezman H, Allegood JC, Sullards MC, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mizutani Y, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Biochem J. 2005;390:263. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pewzner-Jung Y, Ben-Dor S, Futerman AH. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang E, Norred WP, Bacon CW, Riley RT, Merrill AH., Jr J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han X, Gross RW. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1071. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han X, Yang J, Cheng H, Ye H, Gross RW. Anal Biochem. 2004;330:317. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ekroos K, Chernushevich IV, Simons K, Shevchenko A. Anal Chem. 2002;74:941. doi: 10.1021/ac015655c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ejsing CS, Duchoslav E, Sampaio J, Simons K, Bonner R, Thiele C, Ekroos K, Shevchenko A. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6202. doi: 10.1021/ac060545x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ejsing CS, Moehring T, Bahr U, Duchoslav E, Karas M, Simons K, Shevchenko A. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:372. doi: 10.1002/jms.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwudke D, Oegema J, Burton L, Entchev E, Hannich JT, Ejsing CS, Kurzchalia T, Shevchenko A. Anal Chem. 2006;78:585. doi: 10.1021/ac051605m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haynes CA, Allegood JC, Sims K, Wang EW, Sullards MC, Merrill AH., Jr The Journal of Lipid Research. 2008;49:1113. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D800001-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shaner RL, Allegood JC, Park H, Wang E, Kelly S, Haynes CA, Cameron Sullards M, Merrill AH., Jr Journal of Lipid Research. 2008:D800051. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D800051-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McFarland MA, Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL, Nilsson CL, Fredman P, Mansson JE. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:752. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vukelic Z, Zamfir AD, Bindila L, Froesch M, Peter-Katalinic J, Usuki S, Yu RK. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:571. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Connor PB, Costello CE. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1862. doi: 10.1002/rcm.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ivleva VB, Elkin YN, Budnik BA, Moyer SC, O’Connor PB, Costello CE. Anal Chem. 2004;76:6484. doi: 10.1021/ac0491556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jones JJ, Stump MJ, Fleming RC, Lay JO, Jr, Wilkins CL. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1665. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jones JJ, Batoy SM, Wilkins CL. Comput Biol Chem. 2005;29:294. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jackson SN, Wang HY, Woods AS, Ugarov M, Egan T, Schultz JA. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:133. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verbeck GF, Ruotolo Brandon T, Sawyer Holly A, Gillig Kent J, Russell David H. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques. 2002;13:56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu Y, Clemmer David E. Analytical Chemistry. 1997;69:2504. doi: 10.1021/ac9701344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clowers BH, Dwivedi P, Steiner WE, Hill HH, Jr, Bendiak B. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:660. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Woods AS, Jackson SN. AAPS J. 2006;8:E391. doi: 10.1007/BF02854910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Borner K, Nygren H, Hagenhoff B, Malmberg P, Tallarek E, Mansson JE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johansson B. Surface and Interface Analysis. 2006;38:1401. doi: 10.1002/sia.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thudichum JLW. A treatise on the chemical constitution of the brain. Bailliere, Tindall, and Cox; London: 1884. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alvarez-Vasquez F, Sims KJ, Cowart LA, Okamoto Y, Voit EO, Hannun YA. Nature. 2005;433:425. doi: 10.1038/nature03232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stewart ME, Downing DT. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wertz PW, Downing DT. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:159. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chigorno V, Negroni E, Nicolini M, Sonnino S. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gaskell SJ, Brooks CJ. J Chromatogr. 1976;122:415. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)82263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Flamand N, Justine P, Bernaud F, Rougier A, Gaetani Q. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994;656:65. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rodriguez-Lafrasse C, Rousson R, Pentchev PG, Louisot P, Vanier MT. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226:138. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ribar S, Mesaric M, Bauman M. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2001;754:511. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mano N, Oda Y, Yamada K, Asakawa N, Katayama K. Anal Biochem. 1997;244:291. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lieser B, Liebisch G, Drobnik W, Schmitz G. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:2209. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D300025-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Colsch B, Afonso C, Popa I, Portoukalian J, Fournier F, Tabet JC, Baumann N. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:281. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300331-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bouhours JF, Bouhours D. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Van Veldhoven PP, De Ceuster P, Rozenberg R, Mannaerts GP, de Hoffmann E. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:91. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00739-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khan WA, Dobrowsky R, el Touny S, Hannun YA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;172:683. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ohashi Y, Tanaka T, Akashi S, Morimoto S, Kishimoto Y, Nagai Y. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rubino FM, Zecca L. Organic Mass Spectrometry. 1992;12:1357. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hayashi A, Matsubara T, Nakamura T, Kinoshita T. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 1990;1990:57. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kaneshiro ES, Jayasimhulu K, Sul D, Erwin JA. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:2399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matsubara T, Morita M, Hayashi A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1042:280. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90154-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hsu FF, Turk J. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2001;12:61. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00194-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bielawski J, Szulc ZM, Hannun YA, Bielawska A. Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gu M, Kerwin JL, Watts JD, Aebersold R. Anal Biochem. 1997;244:347. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sullards MC. Methods Enzymol. 2000;312:32. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)12898-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Benaud C, Oberst M, Hobson JP, Spiegel S, Dickson RB, Lin CY. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Imai H, Nishiura H. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:375. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Liliom K, Sun G, Bunemann M, Virag T, Nusser N, Baker DL, Wang DA, Fabian MJ, Brandts B, Bender K, Eickel A, Malik KU, Miller DD, Desiderio DM, Tigyi G, Pott L. Biochem J. 2001;355:189. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kawase M, Watanabe M, Kondo T, Yabu T, Taguchi Y, Umehara H, Uchiyama T, Mizuno K, Okazaki T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1584:104. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dragusin M, Wehner S, Kelly S, Wang E, Merrill AHJ, Kalff JC, van Echten-Deckert G. FASEB J. 2006 doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5518fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sullards MC, Merrill AH., Jr Sci STKE 2001. 2001:PL1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.67.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Murata N, Sato K, Kon J, Tomura H, Yanagita M, Kuwabara A, Ui M, Okajima F. Biochem J. 2000;352(Pt 3):809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hara A, Taketomi T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1975;78:527. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Motta S, Monti M, Sesana S, Caputo R, Carelli S, Ghidoni R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1182:147. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(93)90135-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Okumura K, Hayashi K, Morishima I, Murase K, Matsui H, Toki Y, Ito T. Lipids. 1998;33:529. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liu G, Kleine L, Hebert RL. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;63:187. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cordis GA, Yoshida T, Das DK. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1998;16:1189. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(97)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Weerheim A, Ponec M. Arch Dermatol Res. 2001;293:191. doi: 10.1007/s004030100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Skipski VP, Smolowe AF, Barclay M. J Lipid Res. 1967;8:295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yano M, Kishida E, Muneyuki Y, Masuzawa Y. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:2091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Dasgupta S, Hogan EL. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhou Q, Zhang L, Fu XQ, Chen GQ. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;780:161. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gaskell SJ, Edmonds CG, Brooks CJ. J Chromatogr. 1976;126:591. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)84104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Raith K, Darius J, Neubert RH. J Chromatogr A. 2000;876:229. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hemling ME, Yu RK, Sedgwick RD, Rinehart KL., Jr Biochemistry. 1984;23:5706. doi: 10.1021/bi00319a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Domon B, Vath JE, Costello CE. Anal Biochem. 1990;184:151. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Fujiwaki T, Yamaguchi S, Tasaka M, Sakura N, Taketomi T. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;776:115. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Fujiwaki T, Yamaguchi S, Sukegawa K, Taketomi T. Brain Dev. 2002;24:170. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(02)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fujiwaki T, Tasaka M, Takahashi N, Kobayashi H, Murakami Y, Shimada T, Yamaguchi S. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;832:97. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Coch EH, Kessler G. Clin Chem. 1972;18:490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gasser W, O’Brien J, Schwan D, Wilcockson D, Bitter P. Am J Med Technol. 1977;43:1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Das SK, Steen ME, McCullough MS, Bhattacharyya DK. Lipids. 1978;13:679. doi: 10.1007/BF02533745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Blass KG, Briand RL, Ng DS, Harold S. J Chromatogr. 1980;182:311. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ng HT, Hsu LM, Leung WY, Chen CY. Proc Natl Sci Counc Repub China B. 1987;11:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Fabre E, Martinez MA, Ruiz J, Serrano JL, Veintemilla MJ. Rev Esp Fisiol. 1986;42:171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ramstedt B, Leppimaki P, Axberg M, Slotte JP. Eur J Biochem. 1999;266:997. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Weerheim AM, Kolb AM, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Anal Biochem. 2002;302:191. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Schiller J, Muller K, Suss R, Arnhold J, Gey C, Herrmann A, Lessig J, Arnold K, Muller P. Chem Phys Lipids. 2003;126:85. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(03)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Jungalwala FB, Milunsky A. Pediatr Res. 1978;12:655. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197805000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Jungalwala FB, Hayssen V, Pasquini JM, McCluer RH. J Lipid Res. 1979;20:579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Briand RL, Harold S, Blass KG. J Chromatogr. 1981;223:277. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)80099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.D’Costa M, Dassin R, Bryan H, Joutsi P. Clin Biochem. 1985;18:27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(85)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Ramstedt B, Slotte JP. Anal Biochem. 2000;282:245. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Rombaut R, Camp JV, Dewettinck K. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:482. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Redden PR, Huang YS. J Chromatogr. 1991;567:21. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(91)80305-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Byrdwell WC. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1998;12:256. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19980314)12:5<256::AID-RCM149>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Isaac G, Bylund D, Mansson JE, Markides KE, Bergquist J. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;128:111. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Shimizu A, Ashida Y, Fujiwara F. Clin Chem. 1991;37:1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Murphy RC, Harrison KA. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 1994;13:57. [Google Scholar]

- 166.Kerwin JL, Tuininga AR, Ericsson LH. J Lipid Res. 1994;35:1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Mills K, Eaton S, Ledger V, Young E, Winchester B. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:1739. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Ham BM, Cole RB, Jacob JT. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3330. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Estrada R, Borchman D, Reddan J, Hitt A, Yappert MC. Anal Chem. 2006;78:1174. doi: 10.1021/ac051540n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Huang Y, Shen J, Wang T, Yu YK, Chen FF, Yang J. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2005;37:515. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Schiller J, Arnhold J, Glander HJ, Arnold K. Chem Phys Lipids. 2000;106:145. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Nichols FC, Riep B, Mun J, Morton MD, Bojarski MT, Dewhirst FE, Smith MB. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2317. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400278-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Moreau RA, Young DH, Danis PO, Powell MJ, Quinn CJ, Beshah K, Slawecki RA, Dilliplane RL. Lipids. 1998;33:307. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Helling F, Dennis RD, Weske B, Nores G, Peter-Katalinic J, Dabrowski U, Egge H, Wiegandt H. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:409. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Bektas M, Jolly PS, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Anal Biochem. 2003;320:259. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Rile G, Yatomi Y, Takafuta T, Ozaki Y. Acta Haematol. 2003;109:76. doi: 10.1159/000068491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Johns DG, Webb RC, Charpie JR. J Hypertens. 2001;19:63. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Bodennec J, Pelled D, Futerman AH. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:218. doi: 10.1194/jlr.d200026-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Igisu H, Suzuki K. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Hikita T, Tadano-Aritomi K, Iida-Tanaka N, Anand JK, Ishizuka I, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Kwon OS, Newport GD, Slikker W., Jr J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1998;720:9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Cecconi O, Ruggieri S, Mugnai G. J Chromatogr. 1991;555:267. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)87188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Hara A, Taketomi T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1986;100:415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Whitfield PD, Sharp PC, Taylor R, Meikle P. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]