Introduction

Because chronic illnesses are the foremost health problem globally; many people are faced with the task of adapting to a chronic health condition. Adapting is the process whereby thinking and feeling individuals use conscious awareness and choice to create human and environmental integration (Roy & Andrews, 1999). Yet, there is much to be learned about the adaptation process and strategies that will promote more positive adaptive responses to chronic illnesses (Pollock, 1993). The definition of nursing includes “alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human responses” (ANA, 2003), and nursing research plays a key role in identifying the predictors of adaptation to chronic illness (diagnosis) and designing nursing models (treatment frameworks) that will maximize successful adaptation (human response). The utility of a nursing model is to provide a frame of reference for explaining the components of the human responses to be studied and facilitating the synthesis of relationships among these components with the ultimate purpose of guiding nursing practice (Pollock, Frederickson, Carson, Massey, & Roy, 1994). The purpose of this article is to describe the evolution of “The Women to Women Conceptual Model for Adaptation to Chronic Illness” from its inception to its current permutation.

The Women to Women Program

The Women to Women (WTW) project has been described in detail in several publications, thus only a brief review will be provided here (Cudney & Weinert, 2000; Weinert, Cudney, & Winters, 2005). WTW is a computer-based research intervention designed to provide support and health information to middle-aged women who are chronically ill and live in rural areas of the western United States -- Montana, Wyoming, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. The following summary of the phases of WTW will sketch the project design, describe major outcomes, and trace the trajectory of the conceptual thinking of the research team.

Phase One

The goal of WTW Phase One (1995–2000) was to determine the impact of a 5-month, computer-based research intervention on the social support of chronically ill rural women who participated in asynchronous online discussion forums that allowed them to exchange feelings and discuss health issues. From pilot testing until the end of Phase One, 308 middle-aged women participated either in the intervention or control groups. Social support was defined as “provision for attachment/intimacy, being an integral part of a group, opportunity for nurturant behavior, reassurance of worth, and availability of informational and emotional help” (Weiss, 1969).

The intervention group experienced gains in their social support (Hill, Schillo, & Weinert, 2004) as measured by the Personal Resource Questionnaire-85 (Weinert & Brandt, 1987). Analysis of their online messages revealed a recurring, universal theme that was reflected in their descriptions of their attempts to reconstruct their lives to accommodate their illnesses. This realization indicated a need to broaden the conceptual base for the intervention and to acknowledge that the overarching framework of the study was ‘adaptation to chronic illness’ (Cudney, Winters, Weinert, & Anderson, 2005; Weinert et al., 2005).

Phase Two

In Phase Two (2002–2005), the overall goal of a revised and more sophisticated telehealth intervention was to enhance the potential for rural chronically ill women to better adapt to their chronic illnesses. The length of the intervention was 22 weeks with follow-up extending to 2 years. During Phase Two, 233 women participated in one of three groups: intense intervention, less intense intervention, and control. The intervention group was taught the computer skills necessary to find and discriminately evaluate health information available on the internet, studied online health teaching units, participated in an associated expert-facilitated health education forum, and engaged in an online self-help support group.

Broadening the conceptual framework required the identification of indicators that could be used to measure adaptation to chronic illness. The task was not to incorporate all the possible factors that relate to adaptation, but to select a small part of the explanatory web to be studied or targeted for change (Earp & Ennett, 1991). Psychosocial variables have been found to be better predictors of adaptation than disease activity (McFarlane & Brooks, 1988); therefore, based on the literature and the experience of the investigators, the WTW project targeted psychosocial concepts (social support, self-efficacy, self-esteem, empowerment, depression, loneliness, and stress) as indicators of psychosocial adaptation. To complement these data, the qualitative data embedded in the women’s online exchanges were also examined to gather insights into their experiences.

The intervention had a positive influence on the chosen indicators of adaptation to chronic illness, confirming that they were measurable and amenable to change (Hill, Weinert, & Cudney, 2006). A key element in their adaptive experiences was identified as self-management of chronic illness. It was also seen that their successes and failures in the process of adaptation to chronic illness ultimately impacted the women’s quality of life. The women’s descriptions of the influence of the rural environment on their self-management abilities and adaptation processes confirmed the need to respond to the environmental and social forces that impinge on individuals.

Emerging from these results and descriptions was the realization that there were unanswered questions about and undefined relationships among the factors associated with adaptation to chronic illness that merited investigation, examination, thought, and organization. Based on the WTW data related to the psychosocial indicators of adaptation, the insights of the women participants, and the adaptation work of Roy & Andrews (1999), Stuifbergen, Seraphine, & Roberts (2000), Pollock (1993), Chen (2005), and others, it was deemed that, in Phase Three, a move toward developing a new more complex model of adaptation to chronic illness was warranted.

Phase Three

Currently, the Women to Women Project (2006–2010) design includes two-groups -- a computer intervention group and a control group. A total of eight cohorts will participate in this phase (N=320) with each cohort consisting of 20 intervention and 20 control. The intervention group participates in an 11-week, computer-based intervention in which they have access 24/7 to: (a) self-study health teaching units, (b) a peer-led virtual support group, and (c) the internet. Adaptation variables are measured at baseline, in week 12 and week 24 for both the intervention and control groups.

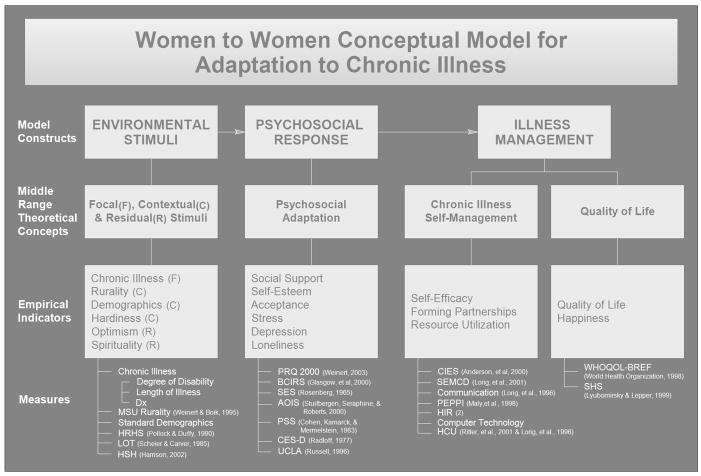

The aims for Phase Three are to: (a) test the effectiveness of the WTW intervention in promoting psychosocial adaptation, fostering self-management, and contributing to an improved quality of life; and (b) explore associations among focal, contextual, and residual stimuli; psychosocial adaptation, chronic illness self-management; and quality of life. The WTW Conceptual Model for Adaptation to Chronic Illness is displayed in Figure 1. (Figure 1 about here.)

Figure 1.

The Women to Women Conceptual Model for Adaptation to Chronic Illness

The WTW Conceptual Model for Adaptation to Chronic Illness

The central theme in “The WTW Conceptual Model for Adaptation to Chronic Illness” is that the process of psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness is key to developing self-management skills and achieving an acceptable quality of life. Adaptation, as delineated in the Roy Adaptation Model (RAM) (Roy & Andrews, 1999), has been a major theoretical construct guiding nursing practice over the past 25 years. Pollock and colleagues (Pollock, 1993; Pollock, Christian, & Sands, 1990) used the RAM as the theoretical framework for integrating the major variables of chronicity, stress, hardiness, and adaptive behavior. Chen (2005) tested the fit of the RAM as a framework for studying the nutritional health and adaptation of community-dwelling elders. Stuifbergen and colleagues (2000) developed the “Model of Health Promotion and Quality of Life in Chronic Disabling Conditions” that associates optimal self-management with quality of life.

From this prior work, the major constructs of the Women to Women model: (a) environmental stimuli, (b) psychosocial response, and (c) illness management were derived. The implied dynamics between these constructs is that individuals are constantly confronted with stimuli from the environment that can elicit psychosocial responses which, in turn, can influence illness management positively or negatively. Associated with each construct are appropriate middle range theoretical concepts and their empirical indicators. The instruments used to measure the empirical indicators were selected based on the strength of their psychometric properties, prior use in research with chronic illness, conceptual fit, and/or previous use by the research team (see Table 1). (Table 1 about here.)

Table 1.

Model Constructs, Theoretical Concepts, Empirical Indicators, Measures

| MODEL CONSTRUCTS |

MIDDLE RANGE THEORETICAL CONCEPTS |

EMPIRICAL INDICATORS |

MEASURES | # OF ITEMS |

RELIABILITY | VALIDITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENVIRONMENTAL STIMULI | Focal (F), Contextual (C), and Residual (R) Stimuli | Chronic Illness (F) | Degree of disability, length of illness, and diagnosis | 5 | N/A | N/A |

| Rurality (C) | MSU Rurality Scale (Weinert & Boik, 1995) | 2 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Demographics (C) | Standard Demographic Information | 19 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Hardiness (C) | Health Related Hardiness Scale(Pollock & Duffy, 1990) | 34 | α = .91 | Convergent | ||

| Optimism (R) | Life Orientation Test (Scheier & Carver, 1985) | 12 | α = .76 | Convergent Discriminant | ||

| Spirituality (R) | Harrison Spirituality Scale (Harrison, 2002) | 33 | α = .87–.93 | Content | ||

| PSYCHOSOCIAL RESPONSE | Psychosocial Adaptation | Social Support | PRQ2000 (Weinert, 2003) | 15 | α = .87–.92 | Construct Divergent |

| Social Support | Brief Chronic Illness Resources Survey.(Glasgow, Strycker, Toobert, & Eakin, 2000) | 29 | α = .79 | Convergent | ||

| Self-Esteem | Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) | 10 | α = .77–.88 | Convergent Discriminant | ||

| Acceptance | Acceptance of Illness Scale (Stuifbergen et al., 2000) | 14 | α = .83 | Content | ||

| Stress | Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) | 18 | α = .84–.86 | Convergent Discriminant | ||

| Depression | CES-D (Radloff, 1977) | 20 | α = .84–.90 | Convergent Discriminant | ||

| Loneliness | UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell,1996) | 20 | α = .94 | Convergent Discriminant | ||

| ILLNESS MANAGEMENT | Chronic Self-Management Illness | Self-Efficacy | Chronic Illness Empowerment Scale (Anderson, Fitzgerald, Funnell, & Marrero, 2000) | 10 | α = .96 | Concurrent |

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease (Lorig, Sobel, Ritter, Laurent, & Hobbs, 2001) | 6 | α = .91 | |||

| Forming Partnerships | Communication with Physicians(Lorig et al., 1996) | 3 | α = .73 | |||

| Forming Partnerships | Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions Questionnaire (Maly, Frank, Marshall, DiMatteo, & Reuben, 1998) | 10 | α = .91 | Construct | ||

| Resource Utilization | Health Information Resources | 11 | ||||

| Resource Utilization | Helpfulness of Health Information Resources | 11 | ||||

| Resource Utilization | Computer Technology | 5 | ||||

| Resource Utilization | Health Care Utilization (Lorig et al., 1996) | 4 | r = .76 – .97 | |||

| Quality of Life | QOL | WHOQOL-BREF (WHOQOL Group, 1998) | 26 | α = .64–.87 | Content Discriminant | |

| QOL | Quality of Life | 1 | ||||

| Happiness | Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) | 4 | α = .79–.94 | Convergent Discriminant |

Environmental Stimuli

Environmental stimuli include three middle range theoretical concepts, and their empirical indicators. These are: (a) focal—those stimuli immediately confronting individuals, i.e., chronic illness; (b) contextual--contributing factors, i.e., degree of rurality, demographics, and hardiness; and (c) residual stimuli--unknown factors that may influence the situation, i.e., optimism, spirituality (Roy & Andrews, 1999).

Focal Stimuli

Focal stimuli are those confronting an individual that necessitate adaptation (Pollock et al., 1994). The focal stimulus that is being targeted for this discussion is chronic illness, which can be defined as a condition of long-term duration, not curable, and/or having some residual features that impose limitations on functional capabilities (Dimond & Jones, 1983). Chronic illness affects all aspects of life including perceptions of stress, social support, and quality of life and may coexist with health in the same individual at any point in the life span. Thus, adaptation to the illness and health maintenance are important to the quality of life of those with chronic health problems.

Contextual Stimuli

Several contextual stimuli are being examined to determine their impact on psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness. These are: degree of rurality, and other demographics, and hardiness.

Degree of rurality and other demographics

Degree of rurality, age, marital status, ethnic identification, education, economic status, number of children, and employment history are empirical indicators of contextual stimuli. Chronic illness disproportionately affects vulnerable populations such as women and those living in rural areas (CDC, 2002) who are most vulnerable to health care quality problems due to demographic factors. In rural areas, travel time, weather conditions, distance, e.g., an average of 57.3 miles, one way, for routine health care (Weinert, 2005), inadequate transportation systems and relatively few health care resources, are barriers to establishing and maintaining support for those managing a chronic illness.

Hardiness

Hardiness is a personal characteristic that reflects commitment, a tendency to appraise demands as challenging rather than threatening, and a sense of control over fate (Pollock, 1989). Kobasa (1982) noted other psychosocial processes, such as adaptation and social support, that may either facilitate or hinder resistance to stress, but suggested that the personality resource of hardiness may very well have a direct effect on the ability to adapt or to utilize social support.

Residual stimuli

The residual stimuli that are being examined are optimism and spirituality. At this point in the thinking of the research team, these are the unknown factors that may influence adaptation.

Optimism

Optimism can be defined as a disposition that is marked by a cross-situation consistent and enduring tendency to expect favorable outcomes. Optimism has been interpreted as a psychosocial disposition that exerts a protective effect on health (O’Brien, VanEgeren, & Mumby, 1995) and can be associated with more successful goal-seeking, lower stress levels, and fewer physical symptoms (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Optimistic people, with a sense of personal control, may have more social support or be more effective at mobilizing it (Taylor & Brown, 1994).

Spirituality

Spirituality is an overreaching human need to understand and develop connections with a larger world and is an integrating force that allows us to be most fully human (Craig, Weinert, Walton, & Derwinski-robinson, 2004). The results of studies tie religious/spiritual practices and beliefs to positive health outcomes (Idler & Kasl, 1997; Morris, 2001; Strawbridge, Cohen, Shema, & Kaplan, 1997) while others indicate that spiritual well-being is associated with overall good health (Brady, Peterman, Fitchett, Mo, & Cella, 1999; Riley et al., 1998). Health outcomes in chronic illness also are linked with spirituality, although the research remains sparse (Craig et al., 2004). (Matthews et al., 1998) noted, from a review of the literature, that religious commitment might help people adapt to illness and facilitate recovery.

Psychosocial Response

The second major construct is psychosocial response with a focus on the middle range theoretical concept of psychosocial adaptation. The empirical indicators of psychosocial adaptation are: social support, self esteem, acceptance, stress, depression, and loneliness.

Social Support

Social support can buffer the negative impact of life events on health (Pollachek, 2001) and positively influence psychosocial adjustment and self-management of chronic illness (Gallant, 2003). Inadequate social support can contribute to increased levels of depression and stress (Connell, Davis, Gallant, & Sharpe, 1994). The consequences of a chronic illness may be buffered by enhancing social support, increasing adherence to treatment recommendations, and promoting overall psychological adaptation (Wortman & Conway, 1985). Because practicing behaviors that promote health may improve quality of life, persons with chronic conditions could benefit from interventions designed specifically to enhance social support (Phillips, 2005). Research supports the notion that greater levels of social support are related to better self-management (Bodenheimer, Lorig, Holman, & Grumbach, 2002).

Self-Esteem

A definition of self-esteem is the extent to which one prizes, values, approves of, or likes oneself (Robinson, Shaver, & Wrightsman, 1991). Self-esteem is indicator of psychological well-being (Heidrich, 1996) and can be considered as one dimension of the potential to manage chronic illness. People who have a positive sense of self-worth, believe in their own control, and are optimistic about the future may be more likely to exhibit better health behaviors (Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Bower, & Gruenewald, 2000). LeMaistre (1995) stated that positive self-esteem is needed for true adaptation because to be psychologically well, while physically sick, implies the belief that your personal worth transcends physical limitations.

Acceptance

Realistic acceptance of chronic illness is proposed by Stuifbergen and colleagues (2000) to have a direct influence on health-promoting behaviors, on optimal self-management, and, ultimately, on an improved quality of life. Acceptance is defined, not as resignation, but as integration of the disease into one’s overall lifestyle. It is the notion that, realistically, one must accept the illness in order to “get on with living.”

Stress

Any agent or stimulus that challenges one’s adaptive capabilities can be considered a stressor (Lawrence & Lawrence, 1979). Although people with chronic illness experience the same kinds of stress as everyone else, they are vulnerable to additional stressors associated with having a chronic illness (Leidy, Ozbolt, & Swain, 1990), e.g., changes in lifestyle, social stigma, self-management tasks, and threats to self-esteem (Devins & Binik, 1996). Developing the capacity to manage stress is often helpful in managing the additional problems of a chronic illness (National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 1994). The perception of the stressor and how to adapt to it are important variables of the adaptation process (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Depression

Depression is common among people with chronic illnesses and can impair the ability to cope, as well as detract from quality of life (Davis & Gershtein, 2003). Fewer depressive symptoms can predict a higher quality of life in adults with various chronic conditions (Patrick, Kinne, Engelberg, & Pearlman, 2000). Psychological and social support resources have a direct favorable effect on depressive symptoms (Bisschop, Kriegsman, Beekman, & Deeg, 2004).

Loneliness

A deficit in human intimacy and negative feelings about being alone (Hall & Havens, 1999) is one definition of loneliness. Chronically ill rural women’s risk for loneliness is compounded by their geographic isolation. Social support is thought to enhance psychological well-being directly by fulfilling one’s need for a sense of coherence and belonging, and thus counteracting feelings of loneliness (Wortman & Conway, 1985).

Illness Management

Illness management is the third major model construct. Chronic illness self-management and quality of life are the middle range theoretical concepts associated with illness management. The empirical indicators for assessing chronic illness self-management are: self-efficacy, forming partnerships with healthcare providers, and resource utilization. Indicators to assess quality of life are: physical condition, psychological status; social relationships; and environment.

Chronic Illness Self-Management

Self-management refers to the daily activities that promote health, manage symptoms, minimize the impact of the chronic illness on functioning, and deal with psychosocial sequelae (Anderson, Funnell, Fitzgerald, & Marrero, 2000). Programs teaching self-management skills are more effective than information-only education in improving clinical outcomes (Gruman & von Korff, 1996). Lorig and Holman (2003) proposed that satisfactory self-management requires the basic skills of problem-solving, resource utilization, and the forming of an individual/health care provider partnership. Essential to accomplishing the core self-management skill of problem-solving is the characteristic of self-efficacy.

Self efficacy

The empirical indicator of self-efficacy can be defined as the confidence that one can carry out a behavior necessary to reach a desired goal. Self-efficacy theory dictates that self-management education requires a focus on problem solving skills (Bandura, 1997) and is related to engagement in health promotion and a higher quality of life (Bodenheimer et al., 2002).

Forming partnerships

To deal with a long-term illness, individuals must be able to accurately report symptoms, make informed choices about treatment, and discuss these with the health care provider. Forming partnerships with one’s care providers is another empirical indicator of one’s ability to self-manage. Self-management training prepares people with chronic illness to become active partners in their care (Lorig & Holman, 2003).

Resource utilization

The ability to find and utilize resources is an empirical indicator of the ability to self-manage (Gustafson et al., 1999). Helping people to optimally self-manage requires teaching them how to seek and use resources, such as using the computer and accessing the internet. More familiar resources such as the phone book, library, and community resource guides are also valuable. Other non-professional resources that can be tapped in time of need are immediate family, friends, neighbors, and coworkers. Chronically ill individuals must sometimes be reminded that identifying the specific kind of assistance they need is often appreciated by those who would like to help but do not know what they can do to contribute to easing the person’s illness burden. It is also important to know when it is appropriate to seek professional assistance. Utilizing these educational modalities and community resources may impact actual health care utilization such as number and quality of office visits to the health care provider.

Quality of Life

If individuals self-manage their chronic illness successfully, it is likely that their quality of life will be enhanced. Quality of life can be defined as individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live as related to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns (Lorig & Holman, 2003) as well as their degree of happiness. There are four empirical indicators of quality of life: physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment (WHOQOL Group, 1994). Self-management education can promote positive perceptions of self, health, and functional ability, and has the potential to greatly enhance quality of life (WHOQOL Group, 1994). While there is no firm consensus on the definition of quality of life, there is some agreement that it is a multidimensional construct, encompassing aspects of perceived psychological, social, and physical well-being (Snoek, 2000).

Well-being, or quality of life, is defined by O’Connor (1993) as the sense of happiness or satisfaction, and reflects a global assessment of all aspects of life. Happiness, its relationship to quality of life, and the tenant that happiness can be lastingly increased, is an emerging concept (Seligman, 2002).

Discussion

Nursing conceptual models are representations of the reality of nursing practice that represent the factors at work and how they are related (Smith, 1994). “Conceptual models are useful for summarizing and integrating the knowledge we have, defining concepts, providing explanations for causal linkages and generating hypotheses” (Earp & Ennett, 1991). Pollock (1993) contended that the potential value of a conceptual model to increase the understanding of adaptation to chronic illness to nursing practice is the development and testing of interventions. Since it is not possible to alter the focal stimulus of chronic illness, emphasis needs to be placed on psychosocial adaptation and illness management. When developing new models based on those that have come before, it must be kept in mind that all constructs and concepts of a given model do not need to be measured in order to contribute to knowledge of adaptation, and other concepts can be added and tested (Pollock et al., 1994). It was from these perspectives that the path of the conceptualization of the Women to Women Project was traced from a single concept base to its present explanatory, multi-concept model consisting of three major adaptation model constructs with related middle range theoretical concepts including empirical indicators and measures for each. The middle range theoretical concepts are useful because they are less abstract and address variables seen in particular situations that are empirically grounded and focus on practical problems and produce more specific indications for practice (Smith, 1994).

The model is continually evolving, and it is anticipated that the current research will further strengthen the notion that interventions that foster positive psychosocial responses to chronic illness, enhance self-management skills, and improve quality of life will promote successful adaptation to chronic illness. Livneh (2001) noted that successful adaptation is reflected in one’s ability to effectively reestablish and manage both the external environment and one’s inner experiences, such as cognitions and feelings, which ultimately ensures the attainment of improved quality of life. Individuals who successfully adapt to their chronic health condition will have more control over their health status and health care, and will live healthier lives.

Conceptual models are dynamic and constantly changing as new evidence emerges -- they are not intended to be static and unchanging. Therefore, by testing the impact of the WTW intervention on psychosocial adaptation, self-management ability, and quality of life, and exploring the impact of the focal, contextual, and residual stimuli, it is expected that evidence will be generated on which to judge the adequacy of the model and indicate areas of ‘goodness of fit’ (Stuifbergen et al., 2000) or areas that need re-examination and modification. The ultimate goal is to achieve a fully developed conceptual model that will serve to further inform nursing research, define research questions, identify fruitful targets of interventions, and impact nursing practice (Earp & Ennett, 1991; Stuifbergen et al., 2000) so as to more effectively assist chronically ill individuals to adapt to living with their chronic health conditions.

References

- ANA. Nursing’s social policy statement. 2. Washington, D. C.: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, Marrero DG. The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(6):739–743. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: WH Freeman Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bisschop MI, Kriegsman DM, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ. Chronic diseases and depression: the modifying role of psychosocial resources. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(4):721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8(5):417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Burden posed by chronic disease. 2002 Retrieved June 2, 2004, from http://www.cdc.gov/washington/overview/chronidis.htm.

- Chen C. A framework for studying the nutritional health of community-dwelling elders. Nursing Research. 2005;54(1):13–21. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Davis WK, Gallant MP, Sharpe PA. Impact of social support, social cognitive variables, and perceived threat on depression among adults with diabetes. Health Psychology. 1994;13(3):263–273. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig C, Weinert C, Walton J, Derwinski-robinson R. I am not alone: Spirituality of chronically ill rural dwellers. Rehbilitation Nursing. 2004;29(5):164–168. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2004.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudney S, Weinert C. Computer-based support groups: Nursing in cyberspace. Computers in Nursing. 2000;18(1):35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudney S, Winters C, Weinert C, Anderson K. Social support in cyberspace: Lessons learned. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2005;30(1):25–29. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2005.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Gershtein C. Screening for depression in patients with chronic illness: Why? Disease Management & Health Outcomes. 2003;11(6):375–378. 374. [Google Scholar]

- Devins DM, Binik YM. Facilitating coping with chronic physical illness. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, application. New York: Wiley; 1996. pp. 640–696. [Google Scholar]

- Dimond M, Jones SL. Chronic illness across the life span. Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Earp J, Ennett T. Conceptual models for health education research and practic. Health Education Research. 1991;6(2):163–171. doi: 10.1093/her/6.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Eakin E. A social-ecologic approach to assessing support for disease self-management: The Chronic Illness Resources Survey. J Behav Med. 2000;23(6):559–583. doi: 10.1023/a:1005507603901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruman J, von Korff M. Indexed bibliography on Self-management for People with Chronic Disease. Washington DC: Center for Advancement in Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Boberg E, Owens BH, Sherbeck C, Wise M, et al. Empowering patients using computer based health support systems. Quality in Health Care. 1999;8(1):49–56. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Havens B. The Effects of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Health of Older Women. Prairie Women’s Health Center of Excellence; Winnipeg: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Rc. Harrison spirituality scale. 2002. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich SM. Mechanisms related to psychological well-being in older women with chronic illnesses: Age and disease comparisons. Research in Nursing Health. 1996;19(3):225–235. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199606)19:3<225::AID-NUR6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill W, Schillo L, Weinert C. Effect of a computer-based intervention on a social support for chronically ill rural women. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2004;29(5):169–173. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2004.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill W, Weinert C, Cudney S. Influence of a computer intervention on the psychological status of chronically ill rural women: Preliminary results. Nursing Research. 2006;55(1):34–42. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl SV. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons II: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52(6):S306–316. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.6.s306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobasa SC. The hardy personality: Toward a social psychology of stress and health. In: Sandeis GS, Sus J, editors. Social psychology of health and illness. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SA, Lawrence RM. A model of adaptation to the stress of chronic illness. Nursing Forum. 1979;18(1):33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1979.tb00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy NK, Ozbolt JG, Swain MAP. Psychophysiological processes of stress in chronic physical illness: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1990;15:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1990.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMaistre J. After the Diagnosis. Berkeley: Ulysses Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Livneh H. Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disablity: A conceptual framework. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2001;44(3):151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Sobel D, Ritter P, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effective Clinical Practice. 2001;4(6):256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Lepper H. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research. 1999;46(2) [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, DiMatteo MR, Reuben DBc. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): Validation of an instrument in older persons. Journal of the Amerian Geriatrics Society. 1998;46(7):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DA, McCullough ME, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Swyers JP, Milano MGc. Religious commitment and health status: A review of the research and implications for family medicine. Archives of Family Medicine. 1998;7(2):118–124. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Brooks PM. Determinants of disability in rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1988;27(1):7–14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/27.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EL. The relationship of spirituality to coronary heart disease. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2001;7(5):96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Coping with Stress. New York: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien W, VanEgeren L, Mumby P. Predicting health behaviors using measures of optimism and perceived risk. Health Values. 1995;19(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor R. Issues in the measurement of health-related quality of life. Melbourne, Australia: National Centre for Health Program Evaluation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D, Kinne S, Engelberg R, Pearlman R. Functional status and perceived quality of life in adults with and without chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53(8):779–785. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L. Analysis of the explanatory model of health promotion and QOL in chronic disabling conditions. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2005;30(1):18–24. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2005.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollachek JB. The Relationship of hardiness, social support, and health promoting behaviors to well-being in chronic illness. Rutgers The State University of New Jersey; Newark, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock S. The hardiness characteristic: A motivating factor in adaptation. Advances in Nursing Science. 1989;11(2):53–62. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock S. Adaptation to chronic illness: A program of research for testing nursing theory. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1993;6(2):86–92. doi: 10.1177/089431849300600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock S, Duffy M. The Health-Related Hardiness Scale: Development and psychometric analysis. Nursing Research. 1990;39(4):218–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock S, Frederickson K, Carson M, Massey V, Roy C. Contributions to nursing science: Synthesis of findings from adaptation model research. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1994;8(4):361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock SE, Christian BJ, Sands D. Responses to chronic illness: Analysis of psychological and physiological adaptation. Nursing Research. 1990;39(5):300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LSc. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Riley BB, Perna R, Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Anderson C, Luera G. Types of spiritual well-being among persons with chronic illness: their relation to various forms of quality of life. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1998;79(3):258–264. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Shaver P, Wrightsman L. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. New York: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Mc. Society and the Adolescent Self-image. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Roy C, Andrews H. The Roy Adaptation Model. 2. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4(3):219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M. Authentic Happiness. New York:NY: The Free Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Models, Theories and Concepts. Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Snoek FJ. Quality of Life: A Closer Look at Measuring Pateints’ Well-Being. Diabetes Spectrum. 2000;13(1):24. [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(6):957–961. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuifbergen A, Seraphine A, Roberts G. An explanatory model of health promotion and quality of life in chronic disabling conditions. Nursing Research. 2000;49(3):122–129. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: separating fact from fiction. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116(1):21–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Bower JE, Gruenewald TL. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):99–109. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C. Women to Women Project: unpublished raw data. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Boik RJ. MSU Rurality Index: Development and evaluation. Research in Nursing Health. 1995;18(5):453–464. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Brandt P. Measuring social support with the Personal Resource Questionnaire. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1987;9(4):589–602. doi: 10.1177/019394598700900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Cudney S, Winters C. Social support in cyberspace: The next generation. Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2005;23(1):7–15. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert Cc. Measuring social support: PRQ2000. In: Strickland O, Dilorio C, editors. Measurement of nursing outcomes: Self care and coping. Vol. 3. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group. The development of the World Health Organization quality of life assessment instrument. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortman CB, Conway TL. The role of social support in adaptation and recovery from physical illness. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]