Abstract

The interactions that may occur between microorganisms in different ecosystems have not been adequately studied yet. We investigated yeast-bacterium interactions in a synthetic medium using different culture associations involving the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica 1E07 and two bacteria, Staphylococcus xylosus C2a and Lactococcus lactis LD61. The growth and biochemical characteristics of each microorganism in the different culture associations were studied. The expression of genes related to glucose, lactate, and amino acid catabolism was analyzed by reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR. Our results show that the growth of Y. lipolytica 1E07 is dramatically reduced by the presence of S. xylosus C2a. As a result of a low amino acid concentration in the medium, the expression of Y. lipolytica genes involved in amino acid catabolism was downregulated in the presence of S. xylosus C2a, even when L. lactis was present in the culture. Furthermore, the production of lactate by both bacteria had an impact on the lactate dehydrogenase gene expression of the yeast, which increased up to 30-fold in the three-species culture compared to the Y. lipolytica 1E07 pure culture. S. xylosus C2a growth dramatically decreased in the presence of Y. lipolytica 1E07. The growth of lactic acid bacteria was not affected by the presence of S. xylosus C2a or Y. lipolytica 1E07, although the study of gene expression showed significant variations.

Complex microbial activities play an important role in numerous biological transformations, such as the cheese-ripening process. The global activity of a mixed microbial community is determined by the functions of each species (e.g., yeast and bacteria), which are strongly influenced by the interactions between the different partners. However, the current knowledge of microbial physiology is generally based on pure-culture studies performed under conditions that are different from those encountered in a complex ecosystem. As a consequence, performing mixed-culture studies is an essential way to get closer to the reality of a complex community.

One key limitation of such studies is the fact that most of the approaches used to study microbial communities are essentially descriptive and examine the influence of one microbial species on another microbial species based only on identification (e.g., 16S rRNA phylogeny) or enumeration (e.g., fluorescent in situ hybridization). Nevertheless, some articles mention the use of DNA biochips with rRNA gene sequences without quantification of the levels of expression (47, 49). Additional insights into functional interactions are difficult to obtain.

In food processes such as cheese making, molecular approaches are still exploratory. Until recently, the transcriptomic approach for studying mixed-culture associations involved only two (25) or three microorganisms (9). Real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR is the most sensitive method for the detection and quantification of gene expression levels, particularly for low-abundance mRNA (8, 39). However, use of this method to study a heterogeneous microbial community presents a scientific challenge. Lactate metabolism and amino acid metabolism play a central role during cheese ripening. Lactate is involved in pH variation (19), and amino acids are precursors for cheese flavor formation (44, 48).

Yarrowia lipolytica is a ubiquitous yeast that naturally occurs in a variety of food products. It has been isolated from dairy products, such as cheese and yoghurt, as well as kefir and shoyu, and from salads containing meat or shrimp (3). Previous studies demonstrated involvement of the yeast Y. lipolytica in the production of cheese aroma compounds (7, 10). Moreover, the impact of Y. lipolytica in association with other ripening yeasts was studied. The results suggested that the presence of this organism inhibited Geotrichum candidum mycelial expansion and affected Debaryomyces hansenii cell viability (31).

However, in most cases, Y. lipolytica lives with other microorganisms, such as lactococci and staphylococci (16, 29). It is therefore important to be able to study the behavior of Y. lipolytica in mixed cultures. The lactic acid bacterium (LAB) Lactococcus lactis was shown to coexist with Y. lipolytica strains in cheese (2). L. lactis is encountered in numerous food fermentation processes, particularly cheese production (11, 24, 37, 45). Its contribution primarily consists of the formation of lactate from the available carbon source, which results in rapid acidification of the food raw material. In addition, starter cultures containing LAB and Staphylococcus xylosus are widely used in the production of fermented sausages to enhance the organoleptic properties of the products (32, 36). Moreover, S. xylosus was found to naturally occur in many food microfloras, such as those in cheese and sausages (30, 45).

In this study, the transcription of three cheese-ripening microorganisms in association was investigated by focusing on glucose metabolism, lactate metabolism, and amino acid metabolism. Due to the difficulty of studying a transcriptional ecosystem in a real food environment, pure and mixed Y. lipolytica 1E07, L. lactis LD61, and S. xylosus C2a batch cultures were grown in a synthetic medium (SM). The growth behavior of each microorganism was analyzed together with nutritional parameters and the levels of expression of target genes involved in important metabolism (amino acids and lactate) in the cheese-ripening process. Possible microbial interactions were investigated by comparison of combinations of one-, two-, and three-species associations for each species. This paper describes an efficient way to investigate the microbial interactions using a transcriptional approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and storage conditions.

The microorganisms used in this work were Y. lipolytica 1E07, S. xylosus C2a, and L. lactis LD61. Y. lipolytica 1E07 was originally isolated from Livarot cheese; it was obtained from the Laboratoire des Micro-organismes d'Interêt Laitier et Alimentaire, Caen, France, and was selected because of its biotechnological potential. S. xylosus C2a was derived from type strain DSM20267 of human skin origin and was cured of its endogenous plasmid, pSX267 (13). L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis LD61 was provided by Soredab (Bongrain, La Boissière-Ecole, France). This strain contains plasmids that allow optimal growth in milk (41). Strains were stored in 5% glycerol-nonfat dry milk at −80°C until they were used.

Culture conditions.

The microorganisms were cultivated in 500-ml flasks containing 100 ml of medium. A preculture of each microorganism was grown in a 100-ml flask containing 20 ml of potato dextrose broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) for the yeast, brain heart infusion broth (Biokar Diagnostc, Beauvais, France) for S. xylosus C2a, and M17 (Biokar Diagnostc, Beauvais, France) for L. lactis LD61. These media were inoculated with 200 μl of a strain stock suspension and incubated for 48 h at 25°C with agitation (100 rpm) for Y. lipolytica 1E07 and S. xylosus C2a. The anaerobic bacterium L. lactis LD61 was cultivated at 30°C without agitation. The precultures served as inocula for the cultures. A defined SM, adapted from the medium described by Otto et al. (34), was used for all culture conditions since it contains the substrates that allowed us to study glucose and amino acid metabolism. It essentially contained 48 components, including glucose as the main carbon source, 19 free amino acids, 14 vitamins, five metallic ions, and four nucleic acid bases (see the supplemental material). The pH of the culture media was adjusted to 6.7. Cultures were incubated at 30°C (100 rpm) for either 14 h or 24 h.

Microbial and substrate analyses.

Viable cell counts, expressed in CFU ml−1, were determined using a standard aerobic plate count procedure. Different media were used for the three microorganisms, as follows: yeast extract glucose chloramphenicol agar (Biokar Diagnostics, Paris, France) for Y. lipolytica, brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 50 mg/liter amphotericin (Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France) for S. xylosus, and M17 agar supplemented with 50 mg/liter amphotericin (Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France) for L. lactis. Colonies were enumerated after incubation for 2 days at 25°C or at 30°C for the LAB.

Amino acid production was analyzed using the ninhydrin method, as previously described by Grunau and Swiader (14).

Glucose and lactate were quantified by performing high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters TCM; Waters, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France) with a cation-exchange column (diameter, 7.8 mm; length, 300 mm; Aminex HPX-87H; Bio-Rad, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) and a thermostat set at 35°C. The culture supernatants were filtered using a polyethersulfone membrane filter (pore size, 0.22 μm; diameter, 25 mm). The mobile phase was sulfuric acid (0.01 N) at a flow rate of 0.6 ml · min−1. Detection of compounds of interest was performed with a Waters 486 tunable UV/visible detector regulated at 210 nm. All compounds were quantified using calibration curves established with pure chemicals.

Genomic DNA extraction.

Yeast or bacterial cultures (5 ml) were centrifuged for 5 min at 5,000 × g, washed with 1 ml of distilled water, and then harvested again by centrifugation for 5 min at 5,000 × g. Fifty-five microliters of TES (50 mM Tris, 0.1 mol liter−1 EDTA, 6.7% sucrose; pH 8) was added to each pellet along with 75 μl of a lysozyme (3 mg)-lyticase (20 μl of a 5,000-U/ml solution) mixture. The mixture was incubated for 60 min at 37°C. Forty microliters of proteinase K (14 mg ml−1) and 100 μl of a sodium dodecyl sulfate solution (20%) were added and incubated for 30 min at 65°C. The solution was mixed every 30 min and then poured into 2-ml tubes containing 200 mg zirconium beads (diameters, 0.1 and 0.5 mm; BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for better efficiency. The tubes were vigorously shaken in a bead beater (Fast-Prep-24; MP Biomedicals, France) by using three 45-s mixing sequences at a speed of 6 m s−1. They were cooled on ice for 5 min before each mixing sequence. After centrifugation for 45 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C, the supernatant was collected. It was transferred to a 2-ml tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and 500 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol/vol; pH 8) was added. The tubes were gently mixed by inversion and then centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. The aqueous phase was treated with RNase A (20 mg/ml; SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and was transferred to two tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). A volume of sodium acetate 3 M corresponding to 1/10 of the final volume and 2 volumes of cool pure ethanol were added. The tubes were then incubated overnight at −20°C. The DNA was recovered by centrifugation for 15 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C, and the pellet was subsequently washed three times with 2 ml of 80% (vol/vol) ethanol. The pellet was then dried for 15 min in an incubator at 42°C and dissolved in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA.

Extraction and purification of total RNA.

Cultures were centrifuged for 5 min at 8,200 × g and 4°C. Each pellet was resuspended in 1.25 ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), and the suspension was poured into 2-ml tubes containing 800 mg zirconium beads (diameters, 0.1 and 0.5 mm; BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). The tubes were vigorously shaken in a bead beater (Fast-Prep-24; MP Biomedicals, France) by using three 60-s mixing sequences at a speed of 6.5 m s−1. They were cooled on ice for 5 min before each mixing sequence. After centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C, the supernatant was collected. It was transferred to a 2-ml tube (Phase Lock Gel Heavy; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and 230 μl of chloroform was added. The tubes were gently mixed by inversion and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube, and an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (pH 4.7) (Sigma) was added. The tubes were gently mixed by inversion and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g and 4°C. The upper phase was collected. An equal volume of 100% ethanol was added to the aqueous phase, after which purification with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were treated with DNase using a DNase Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA quality and quantity were analyzed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA).

Real-time RT-PCR analyses.

The RNA extraction and purification procedures used are described above. In order to study the gene expression of the microorganisms, samples were taken after 14 h of culture. cDNAs were subsequently synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). A mixture containing up to 5 μg of total RNA, random, and deoxynucleoside triphosphate (10 mM) primers was prepared, incubated at 65°C for 5 min, and then placed on ice for at least 1 min. A cDNA synthesis mixture containing 10× RT buffer, MgCl2 (25 mM), dithiothreitol (0.1 M), RNaseOUT (40 U μl−1), and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (200 U μl−1) was added to each RNA-primer mixture and then incubated for 50 min at 50°C. The reaction was stopped by incubation for 5 min at 85°C.

The primers for real-time RT-PCR were designed so that they were about 20 to 25 bases long and had G+C contents of over 50% and melting temperatures of about 60°C. The lengths of the PCR products ranged from 90 to 150 bp. LightCycler software (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was used to select primer sequences. All of the primers were synthesized by Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) (Tables 1, 2, and 3).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for the transcriptomic study of Y. lipolytica 1E07 genes

| Primer | Accession no. | Sequence (5′-3′) | Putative functionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAP1-R | YALI0B16522g | CGACCACAGCAATGACTTTAATA | Amino acid transporter |

| GAP1-F | AACTACTGGAATGAAGCTAACG | ||

| ARO8-R | YALI0E20977g | GGCTCCGACCCAGTTGT | Aromatic amino acid aminotransferase |

| ARO8-F | TTCTCCTCCGCCATCGAGTG | ||

| BAT1-R | YALI0D01265g | GTTGGCTCCCAGCTTCTTGT | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase |

| BAT1-F | CTCTCGGCGTCGGAACC | ||

| BAT2-R | YALI0F19910g | TCCAACGGCCTTGGAGTTCT | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase |

| BAT2-F | CCTCAAGCTCTACTGCTCCGA | ||

| JEN1-R | YALI0D20108g | TTAATGTGAGCGTCACAGATATCAC | Organic acid transporter |

| JEN1-F | AGCTCCAGCACAATAAATAGAACAC | ||

| GHD2-R | YALI0E09603g | CTTGAGGAGCAAATCAATGACC | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| GDH2-F | TCCATGTTCGACGAGAACTAC | ||

| GHD3-R | YALI0F17820g | CTTAGAGTCGGACATGGAGACAAC | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| GDH3-F | TACGTTGAGAAGATGATTGAGTACG | ||

| GND1-R | YALI0B15598g | GATGTCCTGGAAAATCTTCTTAATG | Pentose pathway |

| GND1-F | GATATCATCATTGACGGTGGTAACT | ||

| PGI1-R | YALI0F07711g | GGTTCTCTGTGAAGTTGATCTTGTC | Glycolysis |

| PGI1-F | CTTTGATGACTCCAAGATTCTGTTT | ||

| PYC1-R | YALI0C24101g | CAGAGATAACCATCTCCATCTTCAT | Pyruvate carboxylase |

| PYC1-F | GAAAGATTTCTGTTGAGGACAAGAA | ||

| CHA1-R | YALI0B16214g | TTTCCTCCAGAAGAAGAAAAGAAGT | l-Serine/l-threonine deaminase |

| CHA1-F | TGCTTCTCAAATACGAAACTACACA | ||

| HXT2-R | YALI0F19184g | ATAGAAAAAGTAGTTGGCACCACAG | High-affinity hexose transporter |

| HXT2-F | GAACTCAAGGCTATTGAGAACTCTG | ||

| DLD1-R | YALI0E03212g | AAACGTATTCCTCACCGATAG | Lactate oxidoreductase |

| DLD1-F | TGGCCCTTAAGAAGGAAGAT | ||

| KAD-R | YALI0D08690g | CTACTACTCGGTAAGTAGGCATGGA | 2-Oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase |

| KAD-F | AAAACATGTCCATAAGACCCAGTT | ||

| PDA1-R | YALI0F20702g | TAGATATCCTCAAACAGAACCTTGG | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| PDA1-F | AACGATCCTATTTCTGGTCTCAAG | ||

| PDB1-R | YALI0E27005g | AGTCTTCTTGATGGAGTTGAAAATG | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| PDB1-F | TAAGGATATCACTCTTGTCGGTCAC | ||

| CYB2-R | YALI0E21307g | TGCATCCACTGAGTCTGTTT | LDH |

| CYB2-F | TACATCACCGCTACAGCTCTA | ||

| Act21r | YALI0D08272ga | GGCCAGCCATATCGAGTCGCA | Gene encoding actin |

| Act20 | TCCAGGCCGTCCTCTCCC |

Data from reference 6.

Annotations from Génolevures (http://cbi.labri.fr/Genolevures/).

TABLE 2.

Primers used for the transcriptomic study of S. xylosus C2a genes

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Putative function |

|---|---|---|

| ILVE-R | CCG AAA GTT GAT GAA GAG ACA GTA T | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase |

| ILVE-F | AAT AAG AAG GAC GTA CGC CTA GAA T | |

| GyrA-R | TAC AAT GTT ACC GTT ACG CTC AGT A | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase |

| GyrA-F | ATG TTA CAA ATG CTG AAA GTG ATG A | |

| LDH-R | TCT TCA ATT CTG TGT TGT CTT TCA G | Putative 1-phosphofructokinase |

| LDH-F | ATT AGC AGA AGA ATT TGG TGT TTC A | |

| pgiA-R | ACG ACA AAT GTT TCA TAA CCT TCA T | NADH oxidase |

| pgiA-F | AAA TCA GGT ACT ACG ACT GAA CCA G | |

| PDHA-R | TCA ACA ACT GTT TGT TTT TCA GTG T | Pyruvate oxidase |

| PDHA-F | GAA AAA GGA TCC ATT AGT ACG CTT T | |

| PDHB-R | CTA GAG CTA AAC CAC CAA TAC CAG A | Mannose-specific phosphotransferase system component IID |

| PDHB-F | AAA CCG AAT TAC AAA ATG ATG AAA A | |

| Lac-permease-R | CCA TCT GTC CAT TCT TCT TTA GGT A | Lactate permease |

| Lac-permease-F | GCT AGC GCT AAT TGG TAT TGT GTA T | |

| Glucose transporter-R | GTA CAA AGG CTG CAA TAA CGA TAA G | Glucose transporter |

| Glucose transporter-F | CAA AAG TTG GTG TAG CGA CTA GTT T | |

| AA transporter-R | ATC GCT TTT ACT TTA GCG TTA GGT T | Amino acid transporter |

| AA transporter-F | TAG CAA AAT CTA AAG GTG CAG AAC T | |

| GyrA-R | TAC AAT GTT ACC GTT ACG CTC AGTA | DNA gyrase subunit A |

| GyrA-F | ATG TTA CAA ATG CTG AAA GTG ATG A |

TABLE 3.

Primers used for the transcriptomic study of L. lactis LD61 genes

| Primer | Accession no. | Sequence (5′-3′) | Putative function |

|---|---|---|---|

| pgiA-R | L0012 | TCT TTA CCT TGC AAG TAT CCA AGT C | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase |

| pgiA-F | TTC AGC TAA CTT CTC AAC AGA CCT T | ||

| BcaT-R | L0086 | GTT TGC TTT CAC CA TTG TTT AAC T | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase |

| BcaT-F | ATT AAA AGC CTA TCG AAC AAA GGA T | ||

| LacC-R | L0032 | CAA AGA TTG CTT CTA GTT CTT CTC G | Putative 1-phosphofructokinase |

| LacC-F | GTG AAG ATT TCT ATG AGC GTT TGA T | ||

| noxE-R | L196579 | ATT TCC TGC AAT TAT TTC ACT CTT G | NADH oxidase |

| noxE-F | AAT CGG CCT AGA AGT TTC ATT TAG T | ||

| poxL-R | L0199 | GAT GCC AAA CTG ACA ATT AAG AAA T | Pyruvate oxidase |

| poxL-F | GAT GCC AAA CTG ACA ATT AAG AAA T | ||

| ptnD-R | L147466 | CTG GTT TAC AGT ACG TCC TAT CGT T | Mannose-specific phosphotransferase system component IID |

| ptnD-F | CTT TAG TGA TTG CAG AAC CTG ATT T | ||

| purM-R | L165202a | GCC ACT CCA GCC ACA ACT TG | Phosphoribosyl-aminoimidazole synthetase |

| purM-F | GAT TGC GTA GCC ATG TGC GTC |

Data from reference 46.

SYBR green I PCR amplification was performed using a LightCycler (Roche). Amplification was carried out using a 10-μl (final volume) mixture containing 250 ng of an RNA sample, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM primer, and 1 μl of LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR green I (Roche). Five dilutions of cDNA were made to determine the efficiencies of real-time RT-PCR. A negative control without cDNA was systematically included. The amplification procedure involved incubation at 95°C for 8 min for initial denaturation, followed by 40 cycles consisting of (i) denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, (ii) annealing at a temperature that was 5°C below the melting temperature of the primers for 7 s, (iii) extension at 72°C for 6 s, and (iv) fluorescence acquisition (530 nm) at the end of extension. The temperature transition rate was 20°C/s for each step. After real-time RT-PCR, a melting curve analysis was performed by continuously measuring fluorescence during heating from 65 to 95°C at a rate of 0.1°C/s. The cycle threshold (CT) values were determined with the LightCycler software (version 3.3), using the second derivative method. Standard curves were generated by plotting the CT values as a function of the log of the initial RNA concentration. PCR efficiency (E) was then calculated using the following formula: E = 10−1/slope. A suitable internal control gene to normalize the results was used for each microorganism. The actin gene (6) was used for Y. lipolytica, the purine M gene was used for L. lactis, and the gyrase A (46) gene was used for S. xylosus. The Pffafl method (38) was used to calculate the change in transcript abundance normalized to the control gene and relative to a pure culture sample. A statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

(i) Housekeeping gene.

Appropriate normalization strategies are required to control the experimental error introduced during the multistage process required to extract and process RNA. An appropriate housekeeping gene was therefore chosen for each microorganism. An important aspect of the validation procedure is to ensure that the gene chosen for normalization of the RNA expression level is truly invariant under the different sample conditions (data not shown). The actin gene was chosen for Y. lipolytica (6), the purine M gene was chosen for L. lactis, and the gyrase A gene was chosen for S. xylosus (46).

(ii) Confirmation of primer specificity.

Real-time RT-PCR experiments were performed in order to confirm the absence of cross-hybridization between a specific microorganism primer and the other associated microorganisms. All of the primers were tested with DNA samples from the two other microorganisms. In these conditions, no nonspecific hybridization was found. In addition, a LightCycler melting curve analysis was performed by continuously measuring the fluorescence during heating from 65°C to 95°C at a rate of 0.1°C/s. No primer dimers were generated during the 40 real-time RT-PCR amplification cycles that were performed.

(iii) Method of quantification.

The ΔΔCT method uses a single sample, referred to as the calibrator sample, for comparison of every sample's gene expression level. The calibrator sample is analyzed in every assay with the samples of interest. In this study, the calibrator samples were the pure cultures of the microorganisms, and the unknown samples were the mixed cultures. The CT value corresponds to the time (expressed in the number of cycles) at which the reporter fluorescent emission increases beyond a threshold level (based on the background fluorescence of the system). The following formula is used: induction (fold) =  , where ΔΔCT = (CT for the gene of interest in the mixed culture − CT for the housekeeping gene in the mixed culture) − (CT for the gene of interest in the pure culture − CT for the housekeeping gene in the pure culture). The expression in the pure culture thus represents 1× expression of the gene of interest. The major problem in a study of a microbial coculture is that the concentration of each microorganism may vary depending on the association. Consequently, the proportion of the RNA of each microorganism may also fluctuate. The normalization method that we used in the present study has the advantage of circumventing this problem.

, where ΔΔCT = (CT for the gene of interest in the mixed culture − CT for the housekeeping gene in the mixed culture) − (CT for the gene of interest in the pure culture − CT for the housekeeping gene in the pure culture). The expression in the pure culture thus represents 1× expression of the gene of interest. The major problem in a study of a microbial coculture is that the concentration of each microorganism may vary depending on the association. Consequently, the proportion of the RNA of each microorganism may also fluctuate. The normalization method that we used in the present study has the advantage of circumventing this problem.

RESULTS

For simplicity, the following abbreviations were used for the cultures: Y, Y. lipolytica 1E07 pure culture; S, S. xylosus C2a pure culture; L, L. lactis LD61 pure culture; YL, Y. lipolytica 1E07-L. lactis LD61 coculture; YS, Y. lipolytica 1E07-S. xylosus C2a coculture; LS, L. lactis LD61-S. xylosus C2a coculture; and YLS, Y. lipolytica 1E07-L. lactis LD61-S. xylosus C2a coculture.

Growth properties of the microorganisms.

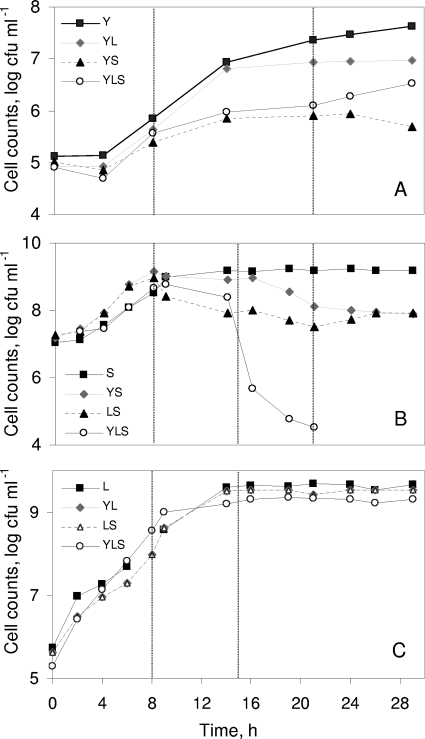

The growth characteristics of the microorganisms as a function of the association are shown in Fig. 1. There was good reproducibility (a difference of less than 0.5 log10 unit) between the results of duplicate experiments.

FIG. 1.

Growth of Y. lipolytica 1E07 (A), S. xylosus C2a (B), and L. lactis LD61 (C) in SM.

Up to 8 h of culture, the cell counts of Y. lipolytica 1E07 were similar in Y, YL, YS, and YLS cultures (Fig. 1A). Between 8 h and 22 h, the presence of L. lactis LD61 in the YL culture slightly decreased the growth of Y. lipolytica 1E07. In the YS and YLS cultures, Y. lipolytica 1E07 cells did not grow to the same high density that they grew to in the Y and YL cultures, and the concentration reached 106 CFU ml−1 at 22 h. At 29 h, the concentration of Y. lipolytica 1E07 was 100-fold lower in the YS culture than in the Y culture.

Up to 8 h in the YLS culture, the presence of L. lactis LD61 or Y. lipolytica 1E07 had no impact on the growth of S. xylosus C2a (Fig. 1B). From 8 to 15 h, S. xylosus C2a growth reached the stationary phase in the S culture (109 CFU ml−1) and in the YS culture (109 CFU ml−1). In addition, in the LS and YLS cultures, the S. xylosus C2a cell counts steadily decreased, and the concentration reached 108 CFU ml−1 at 15 h. At 20 h, the cell counts of S. xylosus C2a in the YLS culture were 10,000-fold lower than those in the S culture. The growth of L. lactis LD61 was similar regardless of the culture (Fig. 1C).

pH, glucose, lactate, and amino acid dynamics.

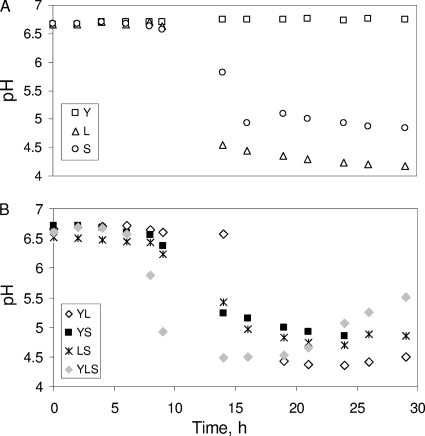

Changes in pH are shown in Fig. 2. The results showed that at 29 h, the pH dropped to 4.2 and 5 in the L and S cultures, respectively (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the pH decreased in the YL, YS, LS, and YLS cultures (Fig. 2B). The acidification was highly correlated with the lactate production from glucose by S. xylosus C2a and L. lactis LD61 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

pH variation for microorganisms in pure cultures (A) and in mixed cultures (B).

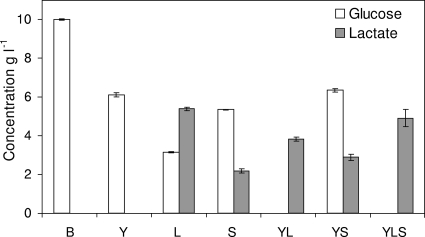

The glucose and lactate concentrations in the supernatants of the microorganism cultures at 14 h are shown in Fig. 3. After 14 h of incubation, 4 g liter−1 of glucose had been consumed by Y. lipolytica 1E07. In pure cultures, L. lactis LD61 and S. xylosus C2a consumed 7 g liter−1 and 5 g liter−1 of glucose, respectively, and produced 5 g liter−1 and 2 g liter−1 of lactate, respectively. Glucose was totally exhausted after 14 h in the YL and YLS cultures, and 4 g liter−1 and 5 g liter−1 of lactate were produced, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Glucose and lactate concentrations in the supernatants of microorganism cultures after 14 h of incubation in SM. B, blank.

Only 4 g liter−1 of glucose was consumed in the YS culture, with production of 2.5 g liter−1 of lactate. High levels of amino acids were consumed in the YS and YLS cultures, and there was greater consumption in the YS culture (threonine, alanine, glutamine, glycine, and lysine were the main amino acids consumed) (data not shown).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the different microorganism associations.

In order to better understand possible interactions between microorganisms, real-time RT-PCR analyses were carried out by focusing on glucose metabolism, lactate metabolism, and amino acid metabolism, which are the main energy sources in the SM. Total RNA was extracted after 14 h of incubation. The time of extraction was chosen so that there were enough cells (the minimum number required is about 106 cells) and so that the culture was at the end of the exponential phase. Real-time RT-PCR analyses were then performed with primers specific for target genes involved in glucose, amino acid, and lactate catabolism.

Levels of expression of the gene transcripts investigated in the different cultures.

The levels of expression of several genes involved in glucose, lactate, and amino acid metabolism were investigated. Seventeen genes were chosen to study the possible effect of S. xylosus C2a and/or L. lactis LD61 on Y. lipolytica 1E07. Real-time RT-PCR was then performed with primers specific for eight genes involved in amino acid catabolism, six genes involved in lactate catabolism, and three genes involved in glucose catabolism (Table 1).

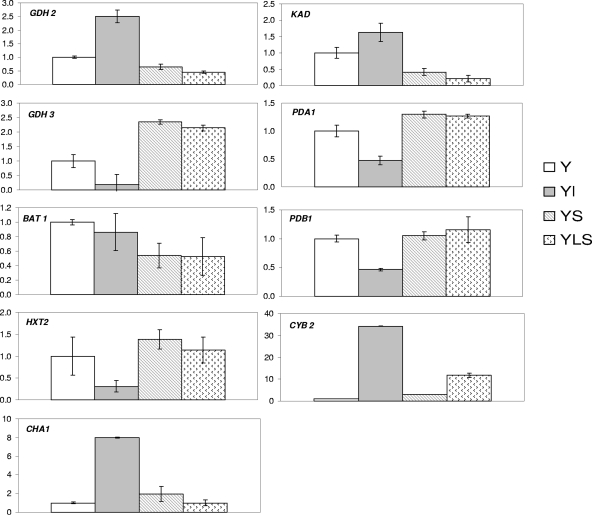

Nine genes of Y. lipolytica whose expression levels significantly differed in the pure and cocultures are shown in Fig. 4. The level of expression of the HXT2 gene involved in glucose catabolism was lower in the pure culture was than in the YL culture, probably due to the total consumption of glucose by L. lactis LD61 at 14 h, which corresponded to the time of RNA extraction. In addition, the levels of expression of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) CYB2 gene were higher in all the cultures in which some lactate was produced than in the Y culture, in which lactate was not produced. The levels of expression of the CYB2 gene were 35, 2.5, and 5 times higher in the YL, YS, and YLS cultures, respectively, than in the pure culture. Moreover, the levels of expression of several genes related to amino acid catabolism, such as BAT1, KAD, and GDH2, were lower in the presence of S. xylosus C2a. Additionally, the induction of the anabolic GDH3 gene encoding the NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase was opposite the induction of the catabolic GDH2 gene encoding an NAD+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. Also, the genes encoding two subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase, PDA1 and PDB1, were induced similarly.

FIG. 4.

Levels of expression of the GDH2, GDH3, BAT1, HXT2, CHA1, KAD, PDA1, PDB1, and CYB2-2 genes, measured by real-time RT-PCR. The levels of expression of genes in a Y culture were compared to those in cocultures after 14 h of incubation in SM.

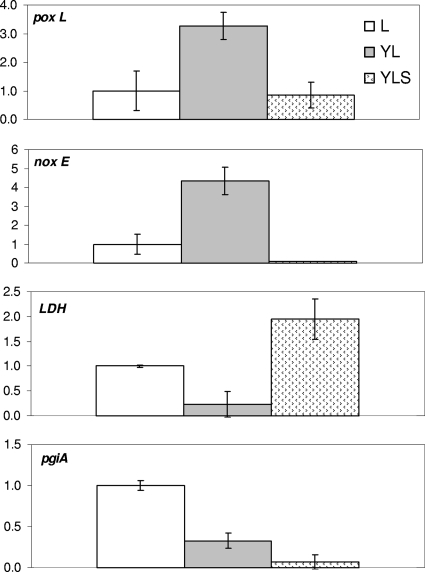

In order to study the effect of S. xylosus C2a and/or Y. lipolytica 1E07 on the gene expression of L. lactis LD61, six genes of L. lactis LD61 were selected; one of these genes is involved in amino acid catabolism, three of these genes are involved in lactate catabolism, and two of these genes are involved in the glucose pathway (Table 3). The levels of expression of four genes were significantly different in coculture and in the L culture (Fig. 5). For instance, the levels of expression of the noxE and poxL genes involved in the oxidative catabolism of glucose or lactate were higher in the YL culture than in the L culture. Moreover, the level of expression of the ldh gene was decreased in the YL culture, whereas it was increased in the YLS culture. At 14 h, glucose was not completely exhausted, which could explain the higher level of expression of the pgiA gene involved in glucose catabolism in the L culture than in the YL and YLS cultures.

FIG. 5.

Levels of expression of the poxL, noxE, ldh, and pgiA genes, measured by real-time RT-PCR. The levels of expression of genes in an L culture were compared to those in cocultures after 14 h of incubation in SM.

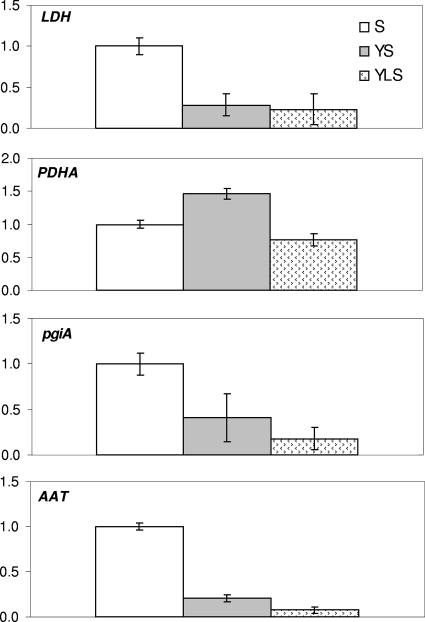

The effect of Y. lipolytica 1E07 and/or L. lactis LD61 on S. xylosus C2a was also investigated. To do this, six genes were selected; one of these genes is involved in amino acid catabolism, three of these genes are involved in lactate catabolism, and two of these genes are involved in the glucose pathway (Table 2). The results for four genes of S. xylosus C2a whose levels of expression significantly differed in the pure and mixed cultures are shown in Fig. 6. These results show that the level of expression of the LDH gene (ldh) decreased in the YS and YLS cultures compared to the S culture. Furthermore, the level of expression of the gene encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase, which is involved in the catabolism of glucose, was higher in the YS culture, whereas the expression of this gene decreased in the YLS culture. The level of expression of the gene involved in amino acid transport significantly decreased regardless of the microbial association (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Levels of expression of the ldh, pdhA, pgiA, and aat genes, measured by real-time RT-PCR. The levels of expression of genes in an S culture were compared to those in cocultures after 14 h of incubation in SM.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the interactions of three microorganisms and the effects on the levels of expression of genes involved in glucose catabolism, lactate catabolism, and amino acid catabolism were investigated using an SM. To our knowledge, little is known about gene expression in microorganisms in cocultures. Most mixed-culture studies have been limited to a biochemical approach using two (27, 28) or, rarely, more microorganisms (1, 31). Recently, transcriptomic approaches have been developed to investigate possible interactions between two or three microorganisms (9, 17, 25), indicating that such alternative approaches could be used to investigate coculture behavior.

Efficiency of the quantification method.

The method used to generate quantitative values must be taken into account when gene expression data are interpreted. Previous studies have demonstrated the linearity of real-time RT-PCR and described the use of standard curves for relative quantification of target genes. The relative expression of a given gene can be obtained by the ΔΔCT method (38). The housekeeping gene chosen for each microorganism is used to normalize the level of expression of each gene. The expression of the housekeeping gene has to be truly invariant under the different sample conditions used (40). This normalization makes it possible to avoid the problem of cell concentration in different association samples.

Effect of L. lactis LD61 and/or S. xylosus C2a interactions on Y. lipolytica 1E07.

The presence of both bacteria considerably reduced the growth of Y. lipolytica 1E07. The presence of S. xylosus C2a resulted in a 100-fold decrease in the Y. lipolytica 1E07 cell count compared to the pure culture. Competition for amino acids between Y. lipolytica 1E07 and S. xylosus C2a may explain this phenomenon. In fact, the amino acids were dramatically consumed in the YS culture. As a result of the low amino acid concentration in the medium, the expression of genes involved in amino acid catabolism (GDH2, BAT1, and KAD) was downregulated in the presence of S. xylosus C2a, regardless of the type of association (YS and YLS cultures). In addition, the expression of the GDH3 (anabolic) and GDH2 (catabolic) genes coding for an NADP+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase and an NAD+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase, respectively, was induced in the opposite way. DeLuna et al. (12) indicated that the coordinated regulation of the GDH3- and GDH2-encoded enzymes resulted in glutamate biosynthesis and balanced utilization of α-ketoglutarate under respiratory conditions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The increase in the levels of expression of Y. lipolytica 1E07 genes involved in amino acid catabolism strongly suggests that amino acids are preferentially consumed by this yeast. A recent study of Y. lipolytica demonstrated the involvement of this yeast in amino acid degradation (26). It showed that the amino acids are used by Y. lipolytica 1E07 primarily as a main energy source and that lactate is consumed following amino acid depletion. Cholet et al. (10) investigated the patterns of expression of target genes related to l-methionine catabolism and lactate catabolism in this yeast. They found that Y. lipolytica was involved mainly in l-methionine catabolism.

In YL or YLS cultures, lactate produced by L. lactis LD61 from glucose led to a 30-fold increase in the level of expression of the CYB2 LDH gene compared to the expression in a Y. lipolytica 1E07 pure culture in which no lactate was produced. Our results are in good agreement with those of Lodi and Guiard (21), who found that in S. cerevisiae the CYB2 gene was subject to several metabolic controls at the transcription level, including inhibition due to glucose fermentation and induction by lactate. At the same time, the level of expression of the glucose transporter-encoding gene HXT2 was decreased twofold. In fact, after 14 h of culture, the glucose was totally consumed by L. lactis LD61 and partially converted to lactate, which accumulated in the medium. A 50-fold decrease in the expression of the HXT2 gene in glucose-depleted media was also reported by Higgins et al. (15). In contrast, Ozcan and Johnston (35) showed that the transcription of the HXT2 genes of the yeast S. cerevisiae is repressed when glucose levels are high and is induced after glucose is depleted. There are several potential reasons for these discrepancies, including the type of culture, strain differences, microorganism associations, and culture medium composition.

Effects of Y. lipolytica 1E07 and/or S. xylosus C2a interactions on L. lactis LD61.

We found that some genes were differentially expressed depending on the association, despite the fact that the growth of L. lactis LD61 was not affected by the microorganisms with which it was associated.

L. lactis LD61 exhibits homofermentative sugar metabolism with lactate as a major end product under most fermentation conditions. The presence of oxygen results in radical changes in the carbon metabolism of L. lactis (23). It has been shown previously that the principal metabolic shifts observed under aerobic conditions coincided with the induction of NADH oxidase (NOX) activity (4, 23). The overproduction of this enzyme results in a decrease in the NADH/NAD ratios. In fact, as a result of NOX activity, the electrons originating from sugar metabolism are used for reduction of oxygen and not for reduction of pyruvate to lactate. Lopez de Felipe et al. (22) demonstrated that the metabolic level of the key cofactor NADH can change L. lactis from a homolactic bacterium to a bacterium producing high levels of acetoin or diacetyl. Under aerobic conditions, the NADH is used as a substrate by the LDH. As a consequence, when NOX is highly expressed, the LDH activity is low and lactate production is further decreased, which is essentially what was found with our cultures.

The pyruvate produced from the consumption of glucose and/or lactate could be transformed into acetyl-phosphate via the pyruvate oxidase involved in its oxidative decarboxylation. A second pathway could be the conversion of pyruvate into lactate via the LDH. In the YL culture, the level of expression of ldh decreased while the level of expression of pox increased compared to the L culture. This result shows that L. lactis LD61 produces mainly acetyl-phosphate from pyruvate in the presence of Y. lipolytica 1E07.

Opposite regulation of the poxL, noxE, and ldh genes was observed in the YLS culture. This result may suggest that in the presence of S. xylosus, the NADH/NAD ratios are important for the reduction of pyruvate to lactate.

The level of expression of the pgiA gene encoding a glucose-6-phosphate isomerase was lower in the YL and YLS cultures than in the L culture due to total consumption of glucose. In fact, this enzyme is highly regulated, and its activity is correlated with substrate abundance (5).

Effects of L. lactis LD61 and/or Y. lipolytica 1E07 interactions on S. xylosus C2a.

Y. lipolytica 1E07 and/or L. lactis LD61 associated with S. xylosus C2a considerably affected the growth of the latter bacterium. Two main reasons could be responsible for the decrease in the growth of S. xylosus C2a in coculture. The first reason is the acidification of the medium due to lactate production by the LAB and S. xylosus C2a. The effect of pH on the growth of S. xylosus has been studied previously. The results showed that lowering the pH from 6.0 to 4.6 decreased the growth of S. xylosus (42, 43). The second reason is that competition for amino acids may occur in the presence of Y. lipolytica 1E07, which is known to preferentially consume amino acids at the expense of lactate (26). Lincoln et al. (20) found that seven Staphylococcus aureus strains required arginine, proline, cysteine, valine, leucine, and glycine for growth. The same results were obtained by Onoue and Mori (33) using a chemically defined medium. Keller et al. (18) observed that S. aureus could utilize glutamate, proline, histidine, aspartate, alanine, threonine, serine, or glycine as a major energy source. The combination of acidification and amino acid competition could explain the dramatic decrease in the size of the S. xylosus C2a population in the YLS culture. Moreover, as a consequence of the decrease in S. xylosus C2a growth, the expression of all the genes in the mixed culture with Y. lipolytica 1E07 and/or L. lactis LD61 significantly decreased compared to the expression of the genes in the pure culture. The same profile was obtained with the mixed culture with Y. lipolytica 1E07, with the exception of the level of expression of the pyruvate dehydrogenase gene, which was slightly higher than that in the S culture.

This study describes an efficient way to investigate microbial interactions using a transcriptional approach. To obtain a better understanding of the interactions that may occur, it would be interesting to use microarray technology that would provide an overview of the whole-cell response to environmental changes at the transcriptional level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Colle, V. Laroute, and R. Tâche for their technical assistance. We also thank N. Desmasures (Laboratoire des Micro-organismes d'Interêt Laitier et Alimentaire, Caen, France) and Soredab (Bongrain, La Boissière Ecole, France) for providing microbial strains.

S.M. is grateful to the ABIES Doctoral School for awarding her a Ph.D. scholarship. This work was supported by an ANR (French National Research Agency) grant within the framework of the “Genoferment” 2E.11 PNRA program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 August 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addis, E., G. H. Fleet, J. M. Cox, D. Kolak, and T. Leung. 2001. The growth, properties and interactions of yeasts and bacteria associated with the maturation of Camembert and blue-veined cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 69:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Álvarez-Martín, P., A. B. Flórez, A. Hernández-Barranco, and B. Mayo. 2008. Interaction between dairy yeasts and lactic acid bacteria strains during milk fermentation. Food Control 19:62-70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett, J. A., R. W. Payne, and D. Yarrow. 2000. Yeasts: characteristics and identification. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 4.Bassit, N., C.-Y. Boquien, D. Picque, and G. Corrieu. 1993. Effect of initial oxygen concentration on diacetyl and acetoin production by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1893-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhosale, S. H., M. B. Rao, and V. V. Deshpande. 1996. Molecular and industrial aspects of glucose isomerase. Microbiol. Rev. 60:280-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchin-Roland, S., G. D. Costa, and C. Gaillardin. 2005. ESCRT-I components of the endocytic machinery are required for Rim101-dependent ambient pH regulation in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Microbiology 151:3627-3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaïti, C., F. Irlinger, H. E. Spinnler, and E. Engel. 2005. An iterative sensory procedure to select odor-active associations in complex consortia of microorganisms: application to the construction of a cheese model. J. Dairy Sci. 88:1671-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustin, S. A. 2000. Absolute quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 25:169-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cholet, O., A. Henaut, S. Casaregola, and P. Bonnarme. 2007. Gene expression and biochemical analysis of cheese-ripening yeasts: focus on catabolism of l-methionine, lactate, and lactose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2561-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cholet, O., A. Henaut, A. Hebert, and P. Bonnarme. 2008. Transcriptional analysis of l-methionine catabolism in the cheese-ripening yeast Yarrowia lipolytica in relation to volatile sulfur compound biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3356-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corsetti, A., J. Rossi, and M. Gobbetti. 2001. Interactions between yeasts and bacteria in the smear surface-ripened cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 69:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLuna, A., A. Avendano, L. Riego, and A. Gonzalez. 2001. NADP-glutamate dehydrogenase isoenzymes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification, kinetic properties, and physiological roles. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43775-43783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Götz, F., J. Zabielski, L. Philipson, and M. Lindberg. 1983. DNA homology between the arsenate resistance plasmid pSX267 from Staphylococcus xylosus and the penicillinase plasmid pI258 from Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 9:126-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunau, J. A., and J. M. Swiader. 1992. Chromatography of 99 amino acids and other ninhydrin-reactive compounds in the Pickering lithium gradient system. J. Chromatogr. A 594:165-171. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins, V. J., A. G. Beckhouse, A. D. Oliver, P. J. Rogers, and I. W. Dawes. 2003. Yeast genome-wide expression analysis identifies a strong ergosterol and oxidative stress response during the initial stages of an industrial lager fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4777-4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irlinger, F., and A. Morvan. 1997. Taxonomic characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci in ripening flora from traditional French cheese. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:319-328. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakubovics, N. S., S. R. Gill, S. E. Lobst, M. M. Vickerman, and P. E. Kolenbrander. 2008. Regulation of gene expression in a mixed-genus community: stabilized arginine biosynthesis in Streptococcus gordonii by coaggregation with Actinomyces naeslundii. J. Bacteriol. 190:3646-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller, G. M., R. S. Hanson, and M. S. Bergdoll. 1978. Molar growth yields and enterotoxin B production of Staphylococcus aureus S-6 with amino acids as energy sources. Infect. Immun. 20:151-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leclercq-Perlat, M. N., F. Buono, D. Lambert, H. E. Spinnler, and G. Corrieu. 2004. Controlled production of Camembert-type cheeses. Part I. Microbiological and physicochemical evolutions. J. Dairy Res. 71:346-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lincoln, R. A., J. A. Leigh, and N. C. Jones. 1995. The amino acid requirements of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from cases of bovine mastitis. Vet. Microbiol. 45:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lodi, T., and B. Guiard. 1991. Complex transcriptional regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CYB2 gene encoding cytochrome b2: CYP1(HAP1) activator binds to the CYB2 upstream activation site UAS1-B2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3762-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez de Felipe, F., M. Kleerebezem, W. M. de Vos, and J. Hugenholtz. 1998. Cofactor engineering: a novel approach to metabolic engineering in Lactococcus lactis by controlled expression of NADH oxidase. J. Bacteriol. 180:3804-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez de Felipe, F., M. J. C. Starrenburg, and J. Hugenholtz. 1997. The role of NADH-oxidation in acetoin and diacetyl production from glucose in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis MG1363. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:15-19. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lücke, F.-K. 2000. Utilization of microbes to process and preserve meat. Meat Sci. 56:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maligoy, M., M. Mercade, M. Cocaign-Bousquet, and P. Loubiere. 2008. Transcriptome analysis of Lactococcus lactis in coculture with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:485-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansour, S., J. M. Beckerich, and P. Bonnarme. 2008. Lactate and amino acid catabolism in the cheese-ripening yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6505-6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masoud, W., and M. Jakobsen. 2005. The combined effects of pH, NaCl and temperature on growth of cheese ripening cultures of Debaryomyces hansenii and coryneform bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 15:69-77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masoud, W., and M. Jakobsen. 2003. Surface ripened cheeses: the effects of Debaryomyces hansenii, NaCl and pH on the intensity of pigmentation produced by Brevibacterium linens and Corynebacterium flavescens. Int. Dairy J. 13:231-237. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mounier, J., R. Gelsomino, S. Goerges, M. Vancanneyt, K. Vandemeulebroecke, B. Hoste, S. Scherer, J. Swings, G. F. Fitzgerald, and T. M. Cogan. 2005. Surface microflora of four smear-ripened cheeses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6489-6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mounier, J., S. Goerges, R. Gelsomino, M. Vancanneyt, K. Vandemeulebroecke, B. Hoste, N. M. Brennan, S. Scherer, J. Swings, G. F. Fitzgerald, and T. M. Cogan. 2006. Sources of the adventitious microflora of a smear-ripened cheese. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:668-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mounier, J., C. Monnet, T. Vallaeys, R. Arditi, A.-S. Sarthou, A. Helias, and F. Irlinger. 2008. Microbial interactions within a cheese microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:172-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nychas, G. J., and J. S. Arkoudelos. 1990. Staphylococci: their role in fermented sausages. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 19:167S-188S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onoue, Y., and M. Mori. 1997. Amino acid requirements for the growth and enterotoxin production by Staphylococcus aureus in chemically defined media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 36:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otto, R., B. Ten Brink, H. Veldkamp, and W. N. Konings. 1983. The relationship between growth rate and electrochemical proton gradient of Streptococcus cremoris. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 16:69-74. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozcan, S., and M. Johnston. 1995. Three different regulatory mechanisms enable yeast hexose transporter (HXT) genes to be induced by different levels of glucose. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1564-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papamanoli, E., P. Kotzekidou, N. Tzanetakis, and E. Litopoulou-Tzanetaki. 2002. Characterization of Micrococcaceae isolated from dry fermented sausage. Food Microbiol. 19:441-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patrignani, F., R. Lanciotti, J. M. Mathara, M. E. Guerzoni, and W. H. Holzapfel. 2006. Potential of functional strains, isolated from traditional Maasai milk, as starters for the production of fermented milks. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 107:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfaffl, M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfaffl, M. W., and M. Hageleit. 2001. Validities of mRNA quantification using recombinant RNA and recombinant DNA external calibration curves in real-time RT-PCR. Biotechnol. Lett. 23:275-282. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radonic, A., S. Thulke, I. M. Mackay, O. Landt, W. Siegert, and A. Nitsche. 2004. Guideline to reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 313:856-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raynaud, S., R. Perrin, M. Cocaign-Bousquet, and P. Loubiere. 2005. Metabolic and transcriptomic adaptation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis in response to autoacidification and temperature downshift in skim milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8016-8023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Søndergaard, A. K., and L. H. Stahnke. 2002. Growth and aroma production by Staphylococcus xylosus, S. carnosus, and S. equorum—a comparative study in model systems. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 75:99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sørensen, B. B., and M. Jakobsen. 1996. The combined effects of environmental conditions related to meat fermentation on growth and lipase production by the starter culture Staphylococcus xylosus. Food Microbiol. 13:265-274. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spinnler, H. E., C. Berger, C. Lapadatescu, and P. Bonnarme. 2001. Production of sulfur compounds by several yeasts of technological interest for cheese ripening. Int. Dairy J. 11:245-252. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talon, R., I. Lebert, A. Lebert, S. Leroy, M. Garriga, T. Aymerich, E. H. Drosinos, E. Zanardi, A. Ianieri, M. J. Fraqueza, L. Patarata, and A. Lauková. 2007. Traditional dry fermented sausages produced in small-scale processing units in Mediterranean countries and Slovakia. 1. Microbial ecosystems of processing environments. Meat Sci. 77:570-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theis, T., R. A. Skurray, and M. H. Brown. 2007. Identification of suitable internal controls to study expression of a Staphylococcus aureus multidrug resistance system by quantitative real-time PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 70:355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, L., X. Liu, C. W. Schadt, and J. Zhou. 2006. Microarray-based analysis of subnanogram quantities of microbial community DNAs by using whole-community genome amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4931-4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yvon, M., and L. Rijnen. 2001. Cheese flavour formation by amino acid catabolism. Int. Dairy J. 11:185-201. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou, J. 2003. Microarrays for bacterial detection and microbial community analysis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:288-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.