Abstract

Biofilm formation by 102 Bacillus cereus and B. thuringiensis strains was determined. Strains isolated from soil or involved in digestive tract infections were efficient biofilm formers, whereas strains isolated from other diseases were poor biofilm formers. Cell surface hydrophobicity, the presence of an S layer, and adhesion to epithelial cells were also examined.

The Bacillus cereus group includes B. cereus sensu stricto, B. anthracis, and B. thuringiensis, three genetically close pathogenic species. Based on genetic evidence, it has been suggested that they could represent one species (7). B. cereus sensu stricto is itself an opportunistic human pathogen occasionally found to cause various diseases such as endophthalmitis or periodontitis but is more frequently involved in gastrointestinal diseases with diarrheal or emetic syndromes (4, 12). Emetic syndromes result from the presence of cereulide, a heat-stable toxin produced in food before ingestion, whereas diarrheal syndromes require survival of the bacterium in the host digestive tract. B. thuringiensis is an insect pathogen, and B. anthracis causes anthrax, a lethal human disease.

The persistent contamination of industrial food processing systems by B. cereus (12) may facilitate its involvement in gastroenteritis. This persistence is due to spores, which may survive pasteurization, heating, and gamma-ray irradiation (9, 13), and to biofilms, which have been shown to be highly resistant to cleaning procedures (18). Biofilms are also suspected to be involved in bacterial pathogenicity, as they may form on host epithelia (15).

In this study, we wanted to test whether biofilm formation by species of the B. cereus group could be connected to the pathogenicity of the bacterium. For this purpose, we screened a collection of 102 pathogenic (diarrheal, emetic, and oral diseases) and nonpathogenic strains of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis for their capability to form biofilms. As adhesion to inert or living surfaces is a prerequisite for biofilm formation, we have investigated relationships within our collection of strains between biofilm formation and cell surface hydrophobicity, the presence of an S-layer, or adhesion to epithelial cells.

Biofilm-forming capacity in microtiter plates.

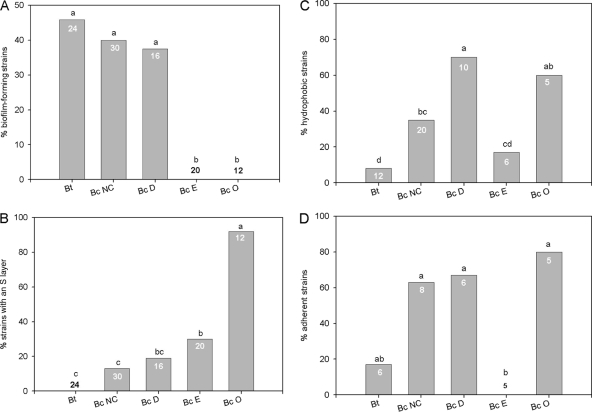

B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains were assayed for biofilm formation by the use of 96-well polyvinylchloride (PVC) microtiter plates (Falcon 35911) and LB medium containing bactopeptone at 30°C as described earlier (2). Under these conditions, the sporulation level was less than 10% after 72 h of culture. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet, and the dye was subsequently solubilized (2). The optical density at 595 nm (OD595) of the solubilized dye ranged from 0.0 to 2.8, and the OD595 threshold value over which strains were considered to be significant biofilm formers was fixed at 0.5. As shown earlier, strong differences between strains with respect to biofilm formation were found (27). However, grouping strains according to their origins revealed significant differences in biofilm production between groups (Fig. 1A). After 72 h of incubation, 37.5% to 47% of B. thuringiensis and nonclinical and diarrheal B. cereus strains had formed biofilms whereas none of the emetic and oral diseases strains had done so, although some emetic strains formed small transient biofilms after 24 h (see Table S2 in the supplementary material). The homogeneity of the emetic group can be explained by its clonal population structure (5). Strains causing oral diseases were all collected from patients with periodontitis disease, with the exception of one strain (AH817) collected from a lichen planus (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). These strains were genetically close but belonged to at least four different serotypes (7). Nonclinical strains of B. cereus were isolated as spores from soil samples and might have included pathogens or symbionts of the insect gut (8). Biofilms may be beneficial to entomopathogenic or diarrheal B. cereus or B. thuringiensis strains by conferring protection against antimicrobial agents and enhancing persistence in the host digestive tract. In contrast, emetic strains are not gut colonizers, as the cereulide is produced outside from the host. Similarly, periodontal strains do not need to form biofilms de novo on host tissues, as they are not involved in dental plaque initiation (10).

FIG. 1.

Bar plots of the frequencies of phenotypes in the different B. thuringiensis and B. cereus groups. (A) Frequencies of strains found to have formed biofilms (after 72 h of incubation) with an OD595 of >0.5 after crystal violet staining. (B) Frequencies of strains displaying an S layer. (C) Frequencies of strains with a hydrophobicity index (LnK) greater than 3. (D) Frequencies of strains adherent to HeLa cells. Figure symbols: bars sharing the same letters (a, b, and c) represent results that were not significantly (P < 0.05) different, as determined by a c2 test; the numbers within bars indicate sample sizes. Bc, B. cereus; Bt, B. thuringiensis; NC, nonclinical; D, diarrheal; E, emetic; O, oral.

Presence of an S layer.

The S layer, a regularly ordered protein layer, is the outermost cell envelope component of numerous archaea and bacteria (22). The presence of an S layer has been described for B. anthracis (6, 16) and for some B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains (11, 14, 17, 24). The presence of the S layer was assayed using the 102 strains tested for biofilm formation by Western blot analysis as described previously (16). None of the 24 B. thuringiensis strains tested here possessed an S layer; however, of the 12 B. cereus oral disease strains, all 11 of the periodontal strains, but not the lichen planus strain, had one. Between these extremes, from 13% to 30% of the nonclinical, diarrheal, and emetic B. cereus strains exhibited an S layer. The differences were significant (Fig. 1B), showing that the presence of the S layer was dependent upon strain origin. The S-layer presence was negatively correlated with biofilm formation in PVC microtiter plates (Pearson coefficient r = −0.28 [P < 0.01]).

Cell surface hydrophobicity.

The hydrophobic properties of planktonic cells grown in LB medium at 30°C and harvested in the early stationary phase at an OD of 3.0 were determined for a subset of 53 strains selected from the 102 strains screened for biofilm formation and S-layer presence. We used an assay examining bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon (3, 21), which measures the distribution of cells between an aqueous and a hydrophobic phase. The equilibrium constant K was calculated as previously described (21) and is expressed as the hydrophobicity index LnK, which spanned a range from −0.38 to 4.58. A strain was considered hydrophobic when the LnK value was greater than 3. Whereas 70% of the diarrheal isolates displayed a hydrophobic surface, only 17% of the emetic strains were hydrophobic, and this difference was significant (Fig. 1C). For the B. thuringiensis, nonclinical B. cereus, and B. cereus oral disease groups, the frequencies of hydrophobic strains were 8%, 35%, and 60%, respectively. Therefore, the diarrheal and oral diseases groups, both of which are involved in mammal tissue infections, displayed the highest hydrophobic scores. The S layer has been suggested to play an important role in attachment to surfaces (23) and has been reported to be involved in cell surface hydrophobicity in studies of B. cereus (11) and lactobacilli (25, 26). However, in our study, hydrophobicity was not positively correlated with biofilm formation in PVC microtiter plates (r = −0.23 [not significant]) or with S-layer presence (r = 0.124 [not significant]).

Adhesion of B. cereus and B. thuringiensis strains to epithelial cells.

In mammals, epithelial cells are the first and major cell type encountered by microorganisms in the mucosa (20) and are the main site of host-pathogen interactions. Adhesion to HeLa epithelial cells was assessed as previously described (19) for a subset of 30 strains selected within the 102 strains screened for biofilm formation and S-layer presence. These 30 strains were all also included in the cell surface hydrophobicity assay. The level of adhesion ranged from 0.003 bacterium per HeLa cell to 1 bacterium per HeLa cell. A strain was considered positive for adhesion to epithelial cells when more than 0.07 bacteria were found to bind to each HeLa cell. Within the oral diseases group, all the periodontal strains were positive for adhesion to epithelial cells, supporting the hypothesis that these strains may be actively involved in dental plaque development. In contrast, the emetic strains, which are not found in the host, were not adherent to epithelial cells. The difference between the B. cereus oral diseases and emetic groups was significant (Fig. 1D). The results determined for the B. cereus diarrheal and nonclinical groups, in which 67% and 63%, respectively, of the strains were positive for adhesion, were also significantly different from those determined for the emetic group. Finally, 16% of the B. thuringiensis strains were positive for adhesion. Whereas no correlation was found between adhesion to epithelial HeLa cells and biofilm formation in experiments using PVC microtiter plates or cell surface hydrophobicity, adhesion was positively correlated with the presence of an S layer (r = 0.335 [P < 0.05]). Previous studies, carried out using four strains, suggested that the B. cereus S layer may promote interactions with human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and other host tissues (11). Here we confirm this link, using 30 strains. In addition, S layers can play an important role in adhesion to extracellular matrix components such as collagens and laminin in Lactobacillus crispatus (1).

In conclusion, our study shows that the ability to form biofilms in PVC microtiter plates at 30°C in LB medium is strongly dependent on the strain origin in the B. cereus group. Strains involved in gut colonization were better biofilms formers. Cell surface hydrophobicity, the presence of an S layer, and adhesion on HeLa epithelial cells were not positively correlated to biofilm formation. However, periodontal strains exhibited specific properties compared to strains of other groups: the presence of an S layer, inability to form a biofilm, and strong adhesion on HeLa cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. A. Okstad (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) for the B. cereus oral disease strains and C. Nguyen-The (INRA, Avignon, France) for the B. cereus emetic strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 July 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antikainen, J., L. Anton, J. Sillanpaa, and T. K. Korhonen. 2002. Domains in the S-layer protein CbsA of Lactobacillus crispatus involved in adherence to collagens, laminin and lipoteichoic acids and in self-assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 46:381-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auger, S., E. Krin, S. Aymerich, and M. Gohar. 2006. Autoinducer 2 affects biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:937-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos, R., and H. Busscher. 1999. Role of acid-base interactions on the adhesion of oral streptococci and actinomyces to hexadecane and chloroform—influence of divalent cations and comparison between free energies of partitioning and free energies obtained by extended DLVO analysis. Colloids Surfaces B 14:169-177. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehling-Schulz, M., M. Fricker, and S. Scherer. 2004. Bacillus cereus, the causative agent of an emetic type of food-borne illness. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 48:479-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehling-Schulz, M., B. Svensson, M. H. Guinebretiere, T. Lindback, M. Andersson, A. Schulz, M. Fricker, A. Christiansson, P. E. Granum, E. Martlbauer, C. Nguyen-The, M. Salkinoja-Salonen, and S. Scherer. 2005. Emetic toxin formation of Bacillus cereus is restricted to a single evolutionary lineage of closely related strains. Microbiology 151:183-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etienne-Toumelin, I., J. C. Sirard, E. Duflot, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 1995. Characterization of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer: cloning and sequencing of the structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:614-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helgason, E., D. A. Caugant, I. Olsen, and A. B. Kolsto. 2000. Genetic structure of population of Bacillus cereus and B. thuringiensis isolates associated with periodontitis and other human infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1615-1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen, G. B., B. M. Hansen, J. Eilenberg, and J. Mahillon. 2003. The hidden lifestyles of Bacillus cereus and relatives. Environ. Microbiol. 5:631-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamat, A. S., D. P. Nerkar, and P. M. Nair. 1989. Bacillus cereus in some Indian foods, incidence and antibiotics, heat and radiation resistance. J. Food Saf. 10:31-41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolenbrander, P. E., N. Ganeshkumar, F. J. Cassels, and C. V. Hughes. 1993. Coaggregation: specific adherence among human oral plaque bacteria. FASEB J. 7:406-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotiranta, A., M. Haapasalo, K. Kari, E. Kerosuo, I. Olsen, T. Sorsa, J. H. Meurman, and K. Lounatmaa. 1998. Surface structure, hydrophobicity, phagocytosis, and adherence to matrix proteins of Bacillus cereus cells with and without the crystalline surface protein layer. Infect. Immun. 66:4895-4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotiranta, A., K. Lounatmaa, and M. Haapasalo. 2000. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bacillus cereus infections. Microbes Infect. 2:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen, H. D., and K. Jorgensen. 1999. Growth of Bacillus cereus in pasteurized milk products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 46:173-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luckevich, M. D., and T. J. Beveridge. 1989. Characterization of a dynamic S layer on Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Bacteriol. 171:6656-6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macfarlane, S., and J. F. Dillon. 2007. Microbial biofilms in the human gastrointestinal tract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102:1187-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesnage, S., E. Tosi-Couture, M. Mock, P. Gounon, and A. Fouet. 1997. Molecular characterization of the Bacillus anthracis main S-layer component: evidence that it is the major cell-associated antigen. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1147-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mignot, T., B. Denis, E. Couture-Tosi, A. B. Kolsto, M. Mock, and A. Fouet. 2001. Distribution of S-layers on the surface of Bacillus cereus strains: phylogenetic origin and ecological pressure. Environ. Microbiol. 3:493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng, J. S., W. C. Tsai, and C. C. Chou. 2002. Inactivation and removal of Bacillus cereus by sanitizer and detergent. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 77:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramarao, N., and D. Lereclus. 2006. Adhesion and cytotoxicity of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis to epithelial cells are FlhA and PlcR dependent, respectively. Microbes. Infect. 8:1483-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos, H. C., M. Rumbo, and J. C. Sirard. 2004. Bacterial flagellins: mediators of pathogenicity and host immune responses in mucosa. Trends Microbiol. 12:509-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg, M., D. Gutnick, and E. Rosenberg. 1980. Adherence of bacteria to hydrocarbons: a simple method for measuring cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 9:29-33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sára, M., and U. B. Sleytr. 2000. S-layer proteins. J. Bacteriol. 182:859-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneitz, C., L. Nuotio, and K. Lounatma. 1993. Adhesion of Lactobacillus acidophilus to avian intestinal epithelial cells mediated by the crystalline bacterial cell surface layer (S-layer). J. Appl. Bacteriol. 74:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidhu, M. S., and I. Olsen. 1997. S-layers of Bacillus species. Microbiology 143(Pt. 4):1039-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smit, E., F. Oling, R. Demel, B. Martinez, and P. H. Pouwels. 2001. The S-layer protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356: identification and characterisation of domains responsible for S-protein assembly and cell wall binding. J. Mol. Biol. 305:245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Mei, H. C., B. van de Belt-Gritter, P. H. Pouwels, B. Martinez, and H. J. Busscher. 2003. Cell surface hydrophobicity is conveyed by S-layer proteins—a study in recombinant lactobacilli. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 28:127-134. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wijman, J. G., P. P. de Leeuw, R. Moezelaar, M. H. Zwietering, and T. Abee. 2007. Air-liquid interface biofilms of Bacillus cereus: formation, sporulation, and dispersion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1481-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.