Abstract

Background

The Hutchinson Study of High School Smoking randomized trial was designed to rigorously evaluate a proactive, personalized telephone counseling intervention for adolescent smoking cessation.

Methods

Fifty randomly selected Washington State high schools were randomized to the experimental or control condition. High school junior smokers were proactively identified (N = 2151). Trained counselors delivered the motivational interviewing plus cognitive behavioral skills training telephone intervention to smokers in experimental schools during their senior year of high school. Participants were followed up, with 88.8% participation, to outcome ascertainment more than 1 year after random assignment. The main outcome was 6-months prolonged abstinence from smoking. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

The intervention increased the percentage who achieved 6-month prolonged smoking abstinence among all smokers (21.8% in the experimental condition vs 17.7% in the control condition, difference = 4.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.2 to 8.1, P = .06) and in particular among daily smokers (10.1% vs 5.9%, difference = 4.1%, 95% CI = 0.8 to 7.1, P = .02). There was also generally strong evidence of intervention impact for 3-month, 1-month, and 7-day abstinence and duration since last cigarette (P = .09, .015, .01, and .03, respectively). The intervention effect was strongest among male daily smokers and among female less-than-daily smokers.

Conclusions

Proactive identification and recruitment of adolescents via public high schools can produce a high level of intervention reach; a personalized motivational interviewing plus cognitive behavioral skills training counseling intervention delivered by counselor-initiated telephone calls is effective in increasing teen smoking cessation; and both daily and less-than-daily teen smokers participate in and benefit from telephone-based smoking cessation intervention.

CONTEXT AND CAVEATS

Prior knowledge

Approximately half of adolescent smokers have tried to quit, but only less than 5% succeed. Results from clinical trials of smoking cessation among adolescents have been variable due to methodological issues.

Study design

Randomized trial of smoking cessation intervention using multiple-component personalized counseling by telephone vs no intervention of more than 2000 high school senior smokers who were proactively identified as high school juniors in 50 schools. The primary outcome was 6-month abstinence from smoking.

Contribution

The intervention increased 6-month abstinence from smoking from 18% to 22%, and more than 88% of students who were followed-up were still participating 1 year after random assignment.

Implications

Smoking cessation intervention using personalized telephone counseling using proactive identification of participants can increase abstinence from smoking among adolescents.

Limitations

Because of the study design, the individual effects of each of the multiple types of intervention could not be determined. More than one-third of the proactively identified participants did not complete one intervention call. The number of minority participants was too small to perform analysis by racial and ethnic minority groups.

From the Editors

An estimated 26.5% of high school seniors smoke monthly (1), which is well above the Healthy People 2010 goal of 16% (2), and 13.6% smoke 10 or more cigarettes daily (1). Teen smokers are at high risk for a lifetime of smoking and associated health problems and premature death (3,4), and these risks also apply to teens who smoke less frequently than daily (5). Although nearly half (49.7%) of all current adolescent smokers report having tried to quit smoking in the past 12 months (1), unfortunately only about 4% per year succeed (6–8).

To address this need, substantial research in teen cessation intervention has been conducted in the past two decades (9–11). This work has revealed important methodological challenges, including poor recruitment and retention, small sample size, short-duration cessation outcome measures, short follow-up periods, and high attrition (11–22). These challenges have, in turn, contributed to conflicting results from adolescent smoking cessation trials. For example, in their 2006 meta-analysis of 48 controlled trials, 19 of which were randomized, Sussman et al. (10) estimated an overall treatment effect equal to an additional 2.9% of participants who quit smoking (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.47 to 4.33, P < .001) across a broad range of studies with different interventions, settings, endpoint definitions, and postintervention follow-up lengths. However, the 2006 Cochrane review (11) identified just 15 trials that were of sufficient quality and had extractable data, and only one of them found statistically significant evidence of an intervention effect (23). They concluded that there was insufficient evidence for judging the effectiveness of specific interventions (11). Also, Garrison et al. (24) examined 281 published studies, of which only six met their strict selection criteria; three reported statistically significant increases in cessation, but only one was a randomized trial. The authors therefore concluded that there was only limited evidence demonstrating efficacy of adolescent smoking cessation interventions and no evidence for long-term effectiveness (24).

Since the period covered by these meta-analyses, additional randomized controlled trials of teen smoking interventions have been reported (25–32), but only one (30) found a treatment effect at 6-month follow-up. The most recent review of the field (22) concluded that “overall, the evidence base for youth smoking cessation is quite modest.” Indeed, to our knowledge, no randomized trial in adolescent smoking cessation has found a statistically significant intervention effect on prolonged (6 months or more) cessation.

Equal in importance to intervention effectiveness is intervention reach; both elements are critical for achieving population impact on teen smokers (33,34). But reaching a large fraction of teen smokers has proven difficult (12,14,16,35,36). For example, only 2%–10% of smokers are typically recruited in school-based smoking cessation programs (14). Major obstacles have included teens’ concerns about participating in cessation interventions,including concerns about privacy (14,35,37–45) and autonomy (39,46), and their lack of enthusiasm for, and misperceptions about, the relevancy, accessibility, and helpfulness of cessation strategies (37,39,46–51). Furthermore, methods that have been used to recruit teens to smoking cessation interventions often require teens to take the first step––for example, to call a phone number, sign up for a program, or attend an informational meeting. Such requirements present additional obstacles to participation (10,12,52).

Clearly, there is a need for more effective interventions that are specifically designed to overcome these challenges of teen smokers (11,24) and that reach out to all those who could benefit from them (12). Testing them rigorously will require randomized controlled trials that address the previously identified methodological challenges (22,11).

Here, we report on the Hutchinson Study of High School Smoking (HS), a group-randomized adolescent smoking cessation trial that included the following elements in its design: proactive identification and contact; inclusion of daily smokers and less-than-daily smokers; inclusion of a selected sample of nonsmokers to protect the confidential status of smoker participants; proactive, counselor-initiated delivery of a personalized telephone counseling intervention that combined motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive behavioral skills training (CBST); and evaluation via a rigorous randomized controlled trial of the intervention effect in terms of prolonged abstinence.

Subjects and Methods

Study Population and Sample Size

The HS trial was conducted in 50 public high schools located throughout Washington State. To achieve the goal of 50 participating high schools, 59 public high schools were randomly selected and contacted for recruitment, yielding a recruitment rate of 84.7%. Reasons for school declines were current involvement in other similar studies (5.1%), unwillingness to provide student and parent names and contact information (5.1%), and lack of time for extra activities (5.1%). The 50 participating schools had an average enrollment of 1224 students (SD = 527.7). The average percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, an indicator of a school’s socioeconomic status, was 24.6 (SD = 13.7%). The communities in which the schools are located included both rural and urban populations, and were diverse in size, ranging in population from under 1000 to nearly 600 000.

The trial cohort consisted of 2151 smokers, identified via self-report using the study-administered baseline classroom survey, which was designed both to identify smokers among high school juniors (ie, students in their penultimate year of high school) for recruitment and to provide baseline data for the trial. Staff administering the baseline classroom survey informed participants, “Some of you may be invited to participate in future research activities.” Also, the last page of this survey requested contact information stating, “We may invite some of you to take part in another activity” and “We’ll use the information below to contact you to see if you want to take part.” Baseline survey procedures have been published (53,54). In the 50 schools, 93.1% (12 141 out of 13 042) eligible juniors completed a baseline survey (53). Of the 901 who did not, 524 (4.0%) did not reply to the follow-up telephone or mailed survey after being absent during the in-class surveys and 377 (2.9%) actively declined (by their own decision or that of their parents). A total of 2175 smokers were identified; 24 (1.1%) declined contact for future activities, leaving 2151 (98.9%) eligible for the study. Smoker participants were 47% female and 25% nonwhite; most were aged 16 (30.5%) or 17 (62%) years. A complete description of baseline characteristics has been published (53).

The sample size of 50 high schools and 2151 teen smokers was sufficiently large to accommodate intraclass correlation of outcome in achieving adequate statistical power: It provided 89% statistical power to detect a 6% absolute difference in smoking cessation percentage between the experimental and control groups.

To capture the varied smoking patterns typical of adolescent smokers, trial participant smokers were defined as those who reported at least monthly smoking via a positive response to any of the following three baseline survey items: 1) How often do you currently smoke cigarettes? (responded: once a month or more, but less than once a week; or once a week or more, but not daily; or at least daily); 2) Have you smoked one or more cigarettes in the last 30 days? (responded: yes); and 3) When was the last time you smoked, or even tried, a cigarette? (responded: 8–30 days ago, or 1–7 days ago, or earlier today). The steps for identifying and recruiting smokers were identical in the control and experimental conditions.

In addition to smokers, a cohort of nonsmokers was included to ensure that contacting individuals for participation in the trial would not reveal a participant's smoking status. This decision was made also to enable the intervention to capitalize on students’ natural proclivity for supporting their smoking peers’ efforts to quit (47,55) and to reinforce nonsmokers’ choice of abstinence and help prevent initiation of smoking during an important developmental period (56). The nonsmoker cohort was selected based on self-report of having close friends who smoke, a willingness to help friends to quit smoking, and an interest in knowing more about how to help others quit smoking; it consisted of 743 (out of 8905) baseline survey respondents who were identified as nonsmokers, and included never smokers (n = 419) and former smokers (n = 324). The latter category consisted of those who reported having smoked regularly in the past, but not for the past 3 months or more, and currently using no other forms of tobacco. Most (80.5%) of the former smokers had not smoked for 6 months and longer.

Experimental Design

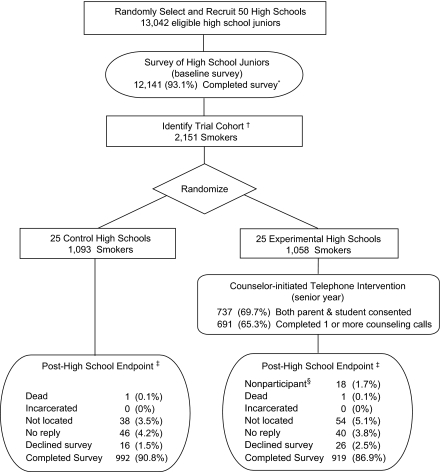

Our trial used a two-arm, group-randomized design (Figure 1). The experimental unit was the high school, chosen to allow for supportive interactions among intervened smokers in the same high school and for any other synergistic effects of the intervention among smokers in a given school, and to mimic future dissemination of the intervention (throughout entire schools) in the event it proved effective. Of 50 participating high schools, 25 were randomly assigned to the experimental (HS cessation intervention) condition and 25 were assigned to the (no-intervention) control condition.

Figure 1.

Hutchinson Study of High School Smoking Experimental Design. *Of the 901 (6.9%) who did not complete a baseline survey, 524 (4.0%) did not respond to multiple survey attempts, and 377 (2.9%) declined. †Twenty-four smokers who declined further contact were excluded. ‡Twelve months postintervention eligibility. §Trial participants who declined study participation during the intervention.

For trial management reasons, the 50 participating high schools were entered into the study in three separate waves separated by 1 year; recruitment was early in the school year (September through December of 2001, 2002, and 2003); baseline data collection was conducted the following spring (ie, March through May of 2002, 2003, and 2004); intervention implementation was during the next school year (ie, September through June of 2003, 2004, and 2005); and follow-up and endpoint data collection was the following year (September through February of 2004, 2005, and 2006). All participants in a wave were assigned to one of six batches that consisted of both experimental and control participants. Each batch's experimental cohort participants were assigned for intervention, one batch every 4 weeks, beginning at the start of the senior year. At the point when experimental participants in a batch became eligible for intervention, all participants in the batch, both experimental and control, were scheduled for outcome survey 12 months later.

Following the intent-to-treat approach (57,58), all 2151 eligible teen smokers at baseline remained part of the trial and were followed up to endpoint, including those who dropped out of school or transferred from the high school or who (in the experimental arm) did not start the intervention or did not complete it once started. The HS trial experimental design, procedures, and intervention were reviewed and approved in advance and annually by the Hutchinson Center's Institutional Review Board. All study outcome measures and analysis plans were specified in advance. The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00115882).

Random Assignment

A matched-pair randomization was performed for each of 25 pairs of high schools matched on prevalence of smoking, number of smokers, stage of readiness to quit, and percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. Schools were randomly ordered within each matched pair, and then, one school in each pair was randomly assigned to the experimental or control condition by a computerized coin flip that was performed openly, witnessed, and recorded.

Intervention

To try to overcome the barriers to intervention reach and effectiveness discussed above, the HS intervention for smokers consisted of the following components: 1) proactive identification of (at least monthly) smokers among enrolled 11th graders via classroom survey––the trial's baseline survey; 2) proactive contact with parents of minor-age smokers to request permission to invite their teen's intervention participation; 3) proactive recruitment via counselor telephone calls of all identified and eligible (by age or parental consent) smokers; 4) protocol-guided, personalized telephone counseling delivered via counselor-initiated calls to intervention participants during their senior year of high school; and 5) two adjunct components supporting the telephone counseling: school-based print and electronic media (eg, posters, brochures, and school newspaper ads promoting nonsmoking norms and intervention participation delivered by project staff to student leadership councils) and a stage-matched, informational smoking cessation Web site tailored to teens.

The telephone counseling and adjunct components, which were based on social cognitive theory (59), were aimed at changing the theoretical processes of smoking and quitting expectancies (ie, perceived value of smoking and quitting), quitting self-efficacy (ie, confidence in one's ability to quit), quitting outcome expectations (ie, perceived outcomes of quitting), behavioral capability (ie, knowledge and skills for quitting), and perceptions of social norms (60–62). Consistent with current guidelines for treatment of tobacco dependence for those not willing to attempt to quit (9), the telephone counseling used MI (63,64) to engage eligible participants, develop rapport, and build and maintain motivation and self-efficacy for quitting. MI was chosen as a primary intervention component because the target population was teen smokers in various stages of the smoking cessation continuum who did not self-select but were proactively recruited to the intervention. CBST was included to build skills for quitting and relapse prevention (65,66).

All counseling calls were planned to be about 15 minutes in duration. The number of calls was personalized to the participant's readiness to quit and progress toward quitting: Once recruited, current smokers not ready to quit were eligible to receive up to three consecutive motivation enhancement calls, which were designed to build intrinsic motivation and confidence to quit. If after three such calls a smoker was not ready to quit, his or her intervention was considered complete. Smokers expressing motivation to quit were eligible for a quit preparation call and up to six cessation support calls designed to strengthen commitment to change, build skills for smoking cessation, and prevent relapse. These latter two types of calls, which focused on skills training, were delivered in a collaborative MI style (eg, counselors asked permission before giving advice); counselors incorporated elements of MI in these calls to maintain and strengthen commitment to quit.

Intervention components and strategies were chosen specifically to address recruitment barriers. For example, delivery of counseling via telephone ensures privacy, gives teens control over the timing and length of counseling sessions, reaches out to teens who typically do not seek cessation assistance, and provides easy access to that help. The companion article, Design and Implementation of an Effective Telephone Counseling Intervention for Adolescent Smoking Cessation (67), provides specifics and rationale for the intervention concept and design, and reports on intervention processes and implementation fidelity.

Outcomes

The outcome survey collected information on abstinence endpoints, which are important for evaluating the intervention's success in terms of smoking cessation, and on progress endpoints, which are needed to measure the intervention's effect on smokers’ progress in quitting. In accordance with recommendations by Mermelstein et al. (15) that endpoint determination occur at least 6 months after the start of intervention, the HS endpoints were collected 1 year after a participant became eligible for intervention. Care was taken to ensure that the timing of outcome determination for the experimental and control conditions was comparable, and that the tracking and data collection staff were blind to experimental vs. control status at outcome data collection and entry.

Abstinence Outcomes.

Three items were included on the outcome survey to measure the trial's abstinence outcomes (6-month, 3-month, 1-month, and 7-day prolonged abstinence): 1) When was the last time you smoked, or even tried, a cigarette? (response choices: I have never smoked, or even tried, a cigarette; earlier today; 1–7 days ago; 8–30 days ago; between 1 and 3 months ago; between 3 and 6 months ago; more than 6 months ago). 2) How often do you currently smoke cigarettes? (response choices: not at all; less than once a month; once a month or more, but less than once a week; at least daily). 3) Think about the last 30 days. On how many of the last 30 days have you smoked one or more cigarettes? (response choices: Every day; 20–29 days; 10–19 days; 5–9 days; 2–4 days; 1 day; 0 days). The main abstinence endpoint for all smokers was 6-month prolonged abstinence [as defined by Velicer et al. (68)], which captures the period of the highest risk of relapse (69). All abstinence endpoints are relevant to both those who (at baseline) were daily smokers or less-than-daily smokers, with the exception of 7-day abstinence, which is relevant only to those who were daily smokers at baseline. Abstinence was defined as consistent reporting of abstinence on all three of the abstinence items. Multiple duration-specific abstinence outcome measures, each requiring consistent reporting, were used in lieu of biochemical validation to support validity of self-report (68–70).

Progress Outcomes.

Progress outcomes, which were selected a priori for their predictive potential for smoking cessation (6,71,72), included: 1) quit attempts in the past 12 months (whether or not had tried to quit, number of quit attempts, category for the longest quit attempt) and 2) change from baseline in readiness to quit, as measured by an adaptation of the contemplation ladder (73), and stages of change (74,75), and 3) reduction from baseline in frequency or in level of smoking (number of cigarettes per day, number of days smoked in the past month, smoking frequency). All of these progress outcomes are relevant to both those who were daily or nondaily smokers at baseline because teens who are infrequent smokers are at risk of becoming daily smokers after high school (3,76,77).

Outcome Data Collection Methods

Using address and telephone information provided by schools, trial participants, parents, and the United States Postal Service, outcome data were collected using a mixed-mode (mail and telephone) sequence of steps (78–80): 1) mailing to the parent(s) of trial participants a request for current locator information for their son or daughter; 2) mailing to the trial participant a survey packet that contained a personalized hand-signed letter, survey, pencil, a $10 bill, and self-addressed stamped envelope; and 3) conducting mail and telephone follow-up of nonresponders. This third step consisted of a reminder post card mailing, nonresponder survey mailings (as needed) at 16, 30, and 47 days after the initial mailing (the second and third of which promised to send $20 in cash on receipt of a completed survey), and nonresponder phone calls that also included a promise of $20 upon survey completion. For participants whose addresses were determined to be no longer current, telephone and web-based tracking were conducted to identify current address and phone number.

Statistical Analysis

The randomization-based permutation method of analysis (81–83) was used, for all smokers, daily smokers, and less-than-daily smokers separately, to evaluate intervention effectiveness and provide two-sided P values and confidence intervals. This method is appropriate for this study's experimental design because its basis for inference is the paired randomization. It does not rely on any modeling or distributional assumptions, and by permuting high schools, intraclass correlation is accommodated.

The random assignment of high schools resulted in good balance of baseline characteristics of smoker trial participants between the experimental and control conditions, with the exception of daily smoking (53). Despite the random assignment, the experimental group included a higher percentage of baseline daily smokers than the control group (39.9% vs 34.5%, P = .02). To control for this baseline imbalance, a stratified statistic Δ = f · ΔD + (1 − f ) · ΔL was used to measure overall intervention impact. It is a sample-size-weighted average of the experimental vs control difference (ΔD) in smoking cessation among baseline daily smokers and the experimental vs control difference (ΔL) in smoking cessation among baseline less-than-daily smokers. The weights f and (1 − f ) are the fractions of baseline smokers who were daily smokers and less-than-daily smokers, respectively.

We considered that results may differ between female and male smokers. To evaluate this possibility, we also reported results by gender.

Results

Telephone Counseling Recruitment and Retention

As previously reported (54), the HS trial was successful in recruiting and retaining a high percentage of eligible adolescent smokers to the smoking cessation telephone counseling intervention: 85.9% (669 out of 779) parents of minor-age smokers provided parental consent, and as a result, 89.9% (948 out of 1058) identified smokers from experimental condition high schools were eligible for intervention (by consent or by age). Overall, 65.3% (691 out of 1058) identified smokers participated in the telephone counseling and nearly half (47.2%) completed all of their scheduled counseling calls.

Telephone Counseling: MI Treatment Integrity

To formally assess MI treatment integrity, a sample of 106 randomly selected recorded smoking cessation counseling sessions were coded using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code, Version 2.0 (84), and analyzed for attainment of established benchmarks for MI quality (84). Benchmarks were achieved for both global assessments (counselor empathy and spirit of MI) and for two of four summary scores of counts of various MI behaviors, indicating fidelity to MI (67).

Participation and Follow-up Rates

Among the 2151 smokers in the HS Study, 1911 (88.8%) were successfully located at follow-up and completed the outcome survey (Figure 1). The average age of participants at the time of outcome survey completion was 18 years and 6 months (range: 16–21 years; SD = 7 months).

Intervention Effects

Main Endpoint: 6-Month Prolonged Smoking Abstinence.

Among all smokers, there was almost conclusive evidence of an intervention effect on 6-month prolonged smoking abstinence at 12 months after becoming intervention eligible (21.8% vs 17.7%, difference = 4.0%, 95% CI = –0.2 to 8.1%, P = .06, Table 1). Among female and male smokers, respectively, the corresponding intervention effects were 5% (95% CI = 0.5 to 10%, P = .03) and 2.9% (95% CI = –4.3 to 9.7%, P = .41). However, there was no evidence that the effect of the intervention differed by gender (P = .58, permutation test for interaction).

Table 1.

Main results. Percentage of baseline smokers who achieved 6-month prolonged smoking abstinence*

| Females |

Males |

All participants |

||||||||||

| Group | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P |

| All smokers (n = 898, 962, 1860)† | 16.2 | 21.1 | 5.0 (0.5 to 9.7) | .03 | 19.4 | 22.3 | 2.9 (−4.3 to 9.7) | .41 | 17.8 | 21.8 | 4.0 (−0.2 to 8.1) | .060 |

| Daily smokers (n = 352, 343, 695) | 5.7 | 7.9 | 1.3 (−3.3 to 5.2) | .56 | 6.2 | 12.2 | 6.3 (2.3 to 9.8) | .006 | 5.9 | 10.1 | 4.1 (0.8 to 7.1) | .02 |

| Less-than-daily smokers (n = 546, 619, 1165) | 22.6 | 29.9 | 7.3 (−0.1 to 14.6) | .053 | 26.7 | 27.7 | 1.0 (−8.8 to 10.6) | .84 | 24.8 | 28.7 | 3.9 (−2.1 to 9.8) | .19 |

Δ = difference: percentage in experimental high schools minus percentage in control high schools (However, whenever some high schools had no baseline smokers in the subgroup of interest, neither these high schools nor their pairs are included in the (matched-pair) permutation test or in the computation of Δ reported here.). CI = confidence interval. P values (two-sided) were calculated using the group-randomized exact permutation test.

n represents the number of valid responses.

Among daily smokers, there was strong evidence of a positive effect of the intervention on 6-months prolonged smoking abstinence (10.1% vs 5.9%, difference = 4.1%, 95% CI = 0.8 to 7.1%, P = .02). A statistically significant effect was observed in particular for male daily smokers (difference = 6.3%, 95% CI = 2.3 to 9.8%, P = .006), but not for female daily smokers (difference = 1.3%, 95% CI = −3.3 to 5.2%, P = .56). Indeed, there is mild evidence (P = .09, not shown in Table 1) that among daily smokers, the intervention effect differed by gender. Among less-than-daily smokers, there was no evidence (P = .19) of intervention impact. Among female less-than-daily smokers, there was marginally significant evidence of intervention impact (increase = 7.3%, 95% CI = −0.1 to 14.6%, P = .053), but there was no evidence (P = .31) that the intervention impact differed by gender.

Shorter-Duration Abstinence Outcomes.

Among all smokers, there was strong evidence of an intervention effect on 1-month and 7-day smoking abstinence and duration since last cigarette (P = .015, .01, and .03, respectively, Table 2); there was only suggestive evidence (P = .09) of an effect on 3-month prolonged abstinence. There was no evidence that the effect of the intervention on any shorter-duration outcome differed by gender (data not shown). For daily smokers, there was strong evidence for a substantial intervention impact on all the shorter-duration abstinence outcomes: 3-month, 1-month, 7-day smoking abstinence, and duration since last cigarette (P = .008, .006, .002, and .003, respectively). Male daily smokers in particular benefited from the intervention, with statistically significant intervention effect on all four short-duration abstinence outcomes, but the intervention effects for female daily smokers were not statistically significant. Intervention-by-gender interactions were statistically significant for three of the four outcomes: 3-month, 7-day smoking abstinence, and duration since last cigarette (P = .04, .03, and .04, respectively). For less-than-daily smokers, there was no evidence of intervention impact on the shorter-duration abstinence outcomes.

Table 2.

Results for shorter-duration abstinence outcomes*

| Females |

Males |

All participants |

||||||||||

| Abstinence outcome | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P |

| All smokers | ||||||||||||

| 3-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 898, 962, 1860)† | 22.6 | 26.5 | 3.9 (−0.6 to 8.8) | .09 | 23.9 | 27.1 | 3.2 (−4.0 to 9.9) | .37 | 23.1 | 26.8 | 3.7 (−0.6 to 7.8) | .09 |

| 1-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 905, 970, 1875) | 29.5 | 34.0 | 4.5 (−0.9 to 9.9) | .10 | 28.3 | 36.8 | 8.5 (1.3 to 14.7) | .02 | 28.7 | 35.5 | 6.8 (1.6 to 11.6) | .015 |

| 7-day smoking abstinence, % (n = 902, 969, 1871) | 41.1 | 46.3 | 5.2 (−0.9 to 11.8) | .09 | 39.6 | 48.8 | 9.2 (1.5 to 16.3) | .02 | 40.0 | 47.5 | 7.5 (1.8 to 13.0) | .013 |

| Duration since last cigarette‡ (n = 905, 970, 1875) | 2.64 | 2.85 | 0.21 (−.03 to .47) | .08 | 2.68 | 3.00 | 0.32 (−.03 to .65) | .07 | 2.65 | 2.93 | 0.28 (.04 to .51) | .03 |

| Daily smokers | ||||||||||||

| 3-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 352, 343, 695) | 9.1 | 11.9 | 1.9 (−3.1 to 6.2) | .42 | 8.0 | 17.7 | 10.2 (4.1 to 15.2) | .003 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 6.2 (2.0 to 10.0) | .008 |

| 1-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 352, 343, 695) | 12.6 | 17.0 | 2.5 (−4.2 to 8.1) | .41 | 11.1 | 23.8 | 13.3 (5.3 to 20.0) | .003 | 11.9 | 20.4 | 8.5 (2.8 to 13.6) | .006 |

| 7-day smoking abstinence, % (n = 352, 343, 695) | 17.1 | 24.9 | 6.1 (−1.3 to 13.2) | .10 | 16.1 | 29.3 | 14.1 (5.0 to 21.7) | .004 | 16.6 | 27.1 | 10.5 (4.3 to 16.1) | .002 |

| Duration since last cigarette‡ (n = 352, 343, 695) | 1.68 | 1.93 | 0.18 (−.09 to .43) | .17 | 1.65 | 2.22 | 0.60 (.27 to .88) | .001 | 1.66 | 2.08 | 0.41 (.17 to .63) | .003 |

| Less-than-daily smokers | ||||||||||||

| 3-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 546, 619, 1165) | 30.9 | 36.1 | 5.1 (−1.4 to 12.2) | .12 | 32.6 | 32.0 | −0.5 (−10.2 to 8.8) | .91 | 31.8 | 34.0 | 2.2 (−3.6 to 7.9) | .44 |

| 1-mo smoking abstinence, % (n = 553, 627, 1180) | 39.8 | 45.5 | 5.7 (−2.7 to 13.9) | .17 | 37.6 | 43.4 | 5.8 (−2.8 to 13.9) | .19 | 38.6 | 44.4 | 5.8 (−0.7 to 11.9) | .076 |

| 7-day smoking abstinence, % (n = 550, 626, 1176) | 55.6 | 60.2 | 4.6 (−4.9 to 14.8) | .33 | 52.3 | 58.9 | 6.6 (−2.7 to 15.6) | .16 | 53.8 | 59.6 | 5.8 (−2.0 to 13.4) | .14 |

| Duration since last cigarette‡ (n = 553, 627, 1180) | 3.22 | 3.45 | 0.24 (−.14 to .63) | .21 | 3.23 | 3.41 | 0.17 (−.28 to .61) | .44 | 3.23 | 3.43 | 0.20 (−.12 to .52) | .21 |

Δ = difference: percentage (or for duration since last cigarette, average) in experimental high schools minus percent or average in control high schools. When some high schools had no baseline smokers in the subgroup of interest, neither these high schools nor their pairs were included in the (matched-pair) permutation test or in the computation of Δ reported here.). CI = confidence interval. P values (two-sided) were calculated using the group-randomized exact permutation test.

n represents the number of valid responses. For some subgroups, n may differ among outcomes due to missing or incomplete responses.

Duration since last cigarette: 1 = earlier today; 2 = 1–7 days ago; 3 = 8–30 days ago; 4 = 1–3 months ago; 5 = 3–6 months ago; 6 = more than 6 months ago; 7 = never smoked.

Cessation-Progress Outcomes.

With respect to quit attempts (Table 3), among all baseline smokers there was marginal but not statistically significant evidence that the intervention had an effect on whether ever tried to quit (in the last 12 months), on the length of the longest quit attempt, and on Abram's composite quitting variable comprising quit duration and number of cigarettes per day (P = .084, .084, .071, respectively). Furthermore, there was an intervention effect among males alone (P = .047, .096, .018, respectively). But only for the composite variable was there evidence that the intervention effect differed by gender (P = .03, not shown in Table 3). With respect to change from baseline in readiness to quit and stage of change, among all participants there was no evidence of an intervention effect. However, for stage of change there was evidence (P = .025) that the intervention effect differed by gender: For males alone, there was some evidence (P = .054) of an effect on the percentage who increased in stage of change (difference = 7.9%, 95% CI = −0.2 to 15.5%). With respect to reduction from baseline in smoking, there was evidence of an intervention effect on reduction in smoking frequency, number of days smoked in last month, and number of cigarettes per day (P = .054, .048, and .048, respectively). Although there was no evidence that intervention effect on these outcomes differed by gender, reduction in these smoking variables was somewhat more pronounced in males (P = .09, .035, and .055, respectively).

Table 3.

Results for progress in cessation outcomes*

| Females |

Males |

All participants |

||||||||||

| Progress endpoints | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P |

| All baseline smokers | ||||||||||||

| Quit attempts | ||||||||||||

| Ever tried to quit, %† (n = 871, 936, 1807) | 64.0 | 66.0 | 2.0 (−4.2 to 9.2) | .52 | 57.5 | 63.1 | 5.6 (0.1 to 10.6) | .047 | 60.7 | 64.5 | 3.9 (−0.6 to 8.4) | .084 |

| No. of quit attempts‡ (n = 844, 909, 1753) | 1.85 | 1.92 | 0.07 (−0.22 to 0.39) | .65 | 1.85 | 2.07 | 0.22 (−0.04 to 0.47) | .092 | 1.85 | 1.99 | 0.14 (−0.08 to 0.36) | .20 |

| Longest quit attempt§ (n = 893, 964, 1857) | 4.80 | 4.91 | 0.11 (−0.15 to 0.38) | .40 | 4.72 | 4.95 | 0.23 (−0.05 to 0.49) | .096 | 4.75 | 4.92 | 0.18 (−0.03 to 0.37) | .084 |

| Composite variable║ (n = 902, 966, 1868) | 1.60 | 1.59 | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.07) | .88 | 1.51 | 1.61 | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.19) | .018 | 1.55 | 1.60 | 0.05 (−0.005 to 0.11) | .071 |

| Change from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Readiness to quit¶ (n = 736, 751, 1487) | 0.85 | 0.81 | −0.04 (−0.36 to 0.30) | .78 | 0.86 | 1.08 | 0.23 (−0.10 to 0.55) | .16 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.09 (−0.14 to 0.32) | .41 |

| Stage of change, %# (n = 749, 765, 1514) | 48.7 | 47.9 | −0.7 (−8.9 to 8.1) | .86 | 43.6 | 51.5 | 7.9 (−0.2 to 15.5) | .054 | 46.0 | 49.7 | 3.7 (−3.0 to 9.9) | .27 |

| Lifetime number of cigarettes** (n = 893, 956, 1849) | 0.60 | 0.54 | −0.06 (−0.17 to 0.05) | .24 | 0.62 | 0.61 | −0.01 (−0.14 to 0.11) | .87 | 0.61 | 0.57 | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05) | .39 |

| Reduction from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Smoking frequency†† (n = 897, 963, 1860) | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.19 (−0.07 to 0.46) | .14 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.26 (−0.05 to 0.53) | .09 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.24 (−0.005 to 0.47) | .054 |

| Days smoked in last mo‡‡ (n = 895, 928, 1823) | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.10 (−0.19 to 0.40) | .49 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.38 (0.03 to 0.68) | .035 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 0.25 (−0.002 to 0.49) | .048 |

| No. of cigarettes per day§§ (n = 895, 958, 1853) | −0.24 | −0.16 | 0.08 (−0.11 to 0.28) | .37 | −0.29 | −0.06 | 0.22 (−0.01 to 0.43) | .055 | −0.26 | −0.11 | 0.16 (0.002 to 0.30) | .048 |

| Baseline daily smokers | ||||||||||||

| Quit attempts | ||||||||||||

| Ever tried to quit, %† (n = 344, 331, 675) | 65.1 | 64.0 | −1.5 (−12.1 to 11.0) | .81 | 52.0 | 61.6 | 9.7 (−6.6 to 23.0) | .21 | 58.9 | 62.8 | 3.9 (−6.8 to 14.3) | .47 |

| No. of quit attempts‡ (n = 332, 320, 652) | 1.80 | 1.69 | −.12 (−.49 to .29) | .55 | 1.41 | 1.71 | 0.32 (−0.04 to 0.61) | .078 | 1.62 | 1.70 | 0.08 (−0.22 to 0.37) | .58 |

| Longest quit attempt§ (n = 349, 342, 691) | 3.67 | 3.62 | −.09 (−.61 to .40) | .71 | 3.46 | 3.94 | 0.51 (0.07 to 0.94) | .025 | 3.57 | 3.78 | 0.22 (−0.16 to 0.56) | .24 |

| Composite variable║ (n = 351, 342, 693) | 1.27 | 1.24 | −.05 (−.23 to .13) | .57 | 1.06 | 1.28 | 0.23 (0.01 to 0.43) | .04 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 0.09 (−0.06 to 0.24) | .25 |

| Change from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Readiness to quit¶ (n = 332, 314, 646) | 0.58 | 0.68 | .02 (−.36 to .40) | .91 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.33 (−0.07 to 0.73) | .10 | 0.64 | 0.83 | 0.19 (−0.08 to 0.46) | .16 |

| Stage of change, %# (n = 336, 310, 646) | 37.0 | 36.8 | −0.8 (−12.0 to 10.6) | .88 | 35.9 | 44.2 | 8.7 (−4.2 to 21.8) | .19 | 36.5 | 40.5 | 4.0 (−4.6 to 12.6) | .36 |

| Lifetime number of cigarettes** (n = 349, 339, 688) | 0.27 | 0.25 | −.01 (−.14 to .13) | .91 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.04 (−0.12 to 0.18) | .62 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.01 (−0.10 to 0.11) | .88 |

| Reduction from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Smoking frequency †† (n = 350, 339, 689) | 0.73 | 0.99 | .20 (−.09 to .48) | .17 | 0.73 | 1.28 | 0.58 (0.20 to 0.92) | .005 | 0.73 | 1.14 | 0.41 (0.15 to 0.64) | .004 |

| Days smoked in last mo‡‡ (n = 350, 332, 682) | 0.89 | 0.93 | −.04 (−.53 to .41) | .88 | 0.65 | 1.49 | 0.89 (0.43 to 1.35) | .001 | 0.78 | 1.21 | 0.43 (0.05 to 0.80) | .028 |

| No. of cigarettes per day§§ (n = 351, 337, 688) | 0.26 | 0.43 | .15 (−.22 to .55) | .41 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 0.49 (0.04 to 0.90) | .033 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.32 (0.08 to 0.54) | .008 |

| Baseline nondaily smokers | ||||||||||||

| Quit attempts | ||||||||||||

| Ever tried to quit, %† (n = 527, 605, 1132) | 63.2 | 67.5 | 4.2 (−4.1 to 12.9) | .31 | 60.5 | 63.8 | 3.4 (−2.1 to 8.9) | .21 | 61.7 | 65.6 | 3.9 (−0.6 to 8.6) | .086 |

| No. of quit attempts‡ (n = 512, 589, 1101) | 1.87 | 2.06 | .19 (−.14 to .54) | .25 | 2.08 | 2.25 | .17 (−0.17 to 0.50) | .31 | 1.99 | 2.16 | 0.17 (−0.06 to 0.41) | .13 |

| Longest quit attempt§ (n = 544, 622, 1166) | 5.50 | 5.73 | .23 (−.14 to .62) | .21 | 5.40 | 5.48 | 0.07 (−0.27 to 0.41) | .65 | 5.45 | 5.60 | 0.15 (−0.10 to 0.41) | .23 |

| Composite variable║ (n = 551, 624, 1175) | 1.80 | 1.82 | .02 (−.06 to.10) | .57 | 1.75 | 1.79 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) | .36 | 1.77 | 1.80 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.09) | .21 |

| Change from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Readiness to quit¶ (n = 404, 437, 841) | 1.04 | 0.95 | −.09 (−.54 to .40) | .67 | 0.97 | 1.10 | 0.16 (−.36 to .68) | .53 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.02 (−0.32 to 0.35) | .91 |

| Stage of change, %# (n = 413, 455, 868) | 58.0 | 57.2 | −0.7 (−11.6 to 11.6) | .91 | 48.8 | 55.8 | 7.4 (−3.5 to 17.9) | .17 | 53.0 | 56.5 | 3.5 (−5.1 to 11.9) | .41 |

| Lifetime number of cigarettes** (n = 544, 617, 1161) | 0.81 | 0.71 | −.10 (−.26 to .07) | .23 | 0.82 | 0.79 | −0.04 (−0.19 to 0.12) | .63 | 0.82 | 0.75 | −0.07 (−0.18 to 0.05) | .27 |

| Reduction from baseline in | ||||||||||||

| Smoking frequency†† (n = 547, 624, 1171) | .03 | 0.22 | .19 (−.22 to .60) | .33 | −0.12 | −0.03 | 0.09 (−0.24 to 0.39) | .56 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.14 (−0.17 to 0.44) | .33 |

| Days smoked in last mo‡‡ (n = 545, 596, 1141) | −.14 | 0.04 | .18 (−.29 to .67) | .44 | −0.19 | −0.09 | 0.10 (−0.31 to 0.46) | .61 | −0.17 | −0.03 | 0.14 (−0.18 to 0.45) | .36 |

| No. of cigarettes per day§§ (n = 544, 621, 1165) | −.56 | −0.52 | .04 (−.22 to .30) | .75 | −0.59 | −0.51 | 0.08 (−0.15 to 0.29) | .45 | −0.58 | −0.51 | 0.06 (−0.11 to 0.23) | .46 |

Δ = difference: percentage or average in experimental high schools minus percentage or average in control high schools. (However, whenever some high schools had no baseline smokers in the subgroup of interest, neither these high schools nor their pairs are included in the [matched-pair] permutation test or in the computation of Δ reported here.) CI = confidence interval. P values (two-sided) were calculated using the group-randomized exact permutation test.

Whether tried to quit (or did not smoke at all) in past12 months.

Number of quit attempts in the past 12 months.

Longest period of time without smoking in the past 12 months. Scale: 1 = less than 24 hours; 2 = 24 hours; 3 = 2–7 days; 4 = 8–30 days; 5 = between 1 and 3 months; 6 = between 3 and 6 months; 7 = six months or more; 8 = I did not smoke at all.

Composite of quit duration and number of cigarettes per day, adapted from Abrams et al. (2000) (85). Scale: 0, 1, 2; one point for reporting 10 or fewer cigarettes per day, plus one point for a quit attempt lasting 7 days or longer in the last 12 months.

Readiness to quit: Scale: 0 = I am not thinking of stopping; 1 = I think I need to consider stopping someday; 2 = I think I should stop, but I’m not quite ready; 3 = I’m starting to think about how to change my smoking patterns; 4 = I’m taking actions now to stop smoking; 5 = Did not smoke in the past month (applicable for outcome value only) (73).

Stage of change. Percentage who increase in stage of change (1 = precontemplation; 2 = contemplation; 3 = preparation; 4 = action; 5 = maintenance (75)).

Lifetime number of cigarettes. Scale: 0 = none; 1 = 1 cigarette, 2 = 2–20 cigarettes; 3 = 21–100 cigarettes; 4 = 101–400 cigarettes; 5 = more than 400 cigarettes.

Smoking frequency. Scale: 0 = not at all; 1 = less than once per month; 2 = once a month or more, but less than once a week; 3 = once a week or more, but less than daily; 4 = daily.

Number of days smoked in past month. Scale: 0 = 0 days; 1 = 1 day; 2 = 2–4 days; 3 = 5–9 days; 4 = 10–19 days; 5 = 20–29 days; 6 = every day.

Number of cigarettes per day. Scale: 0 = nondaily; 1 = 1 cigarette; 2 = 2–5 cigarettes; 3 = 6–10 cigarettes; 4 = 11–20 cigarettes, 5 = more than 20 cigarettes per day.

Intervention Effect by Baseline Quit Attempts and Cessation Stage.

Table 4 shows results for the trial's main outcome by a priori subgroups based on baseline quit attempts (no quit attempts in past year, one or more quit attempts in past year) and baseline stage of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation). For each of the five subgroups, the effect sizes were positive. In particular, among smokers who at baseline had not made any quit attempt in the past year, there was marginal evidence of an intervention effect (difference in percentage of participants who achieved 6-month abstinence = 4.7%, 95% CI = −0.5 to 10.2%, P = .076). Among precontemplative smokers, who make up more than 60% of all smokers, there also was marginal evidence of an intervention effect on 6-month abstinence (difference = 3.9%, 95% CI = −0.4 to 8.4%, P = .07). Among smokers at the preparation stage, a difference in 6-month prolonged smoking abstinence was observed between experimental and control participants (31.7% vs 22.8%, difference = 9.0%, P = .18), but this subgroup was relatively small (n = 314).

Table 4.

Results for 6-month smoking abstinence by baseline subgroups: baseline quit attempts and baseline stage of change*

| Females |

Males |

All participants |

||||||||||

| Baseline subgroup | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P | Control | Experimental | Δ, % (95% CI) | P |

| Quit attempt in past year | ||||||||||||

| None (n = 364, 471, 835) | 15.5 | 22.7 | 7.2 (0.1 to 15.6) | .046 | 16.8 | 20.9 | 4.1 (−5.8 to 14.6) | .41 | 16.0 | 20.8 | 4.7 (−0.5 to 10.2) | .076 |

| One or more (n = 416, 349, 765) | 11.6 | 15.9 | 4.3 (−2.2 to 9.4) | .17 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 0.8 (−7.3 to 7.9) | .84 | 12.9 | 15.8 | 2.9 (−1.9 to 6.9) | .21 |

| Stage of change | ||||||||||||

| Precontemplation (n = 476, 513, 989) | 11.5 | 13.6 | 2.1 (−3.1 to 7.8) | .40 | 12.5 | 17.9 | 5.4 (−1.5 to 12.4) | .12 | 11.9 | 15.8 | 3.9 (−0.4 to 8.4) | .07 |

| Contemplation (n = 159, 132, 291) | 11.7 | 16.9 | 5.2 (−6.6 to 17.7) | .38 | 16.8 | 9.9 | −6.9 (−19.5 to 8.6) | .31 | 13.6 | 14.4 | 0.8 (−8.1 to 10.6) | .86 |

| Preparation (n = 152, 162, 314) | 25.7 | 37.1 | 11.4 (−9.0 to 30.7) | .25 | 22.3 | 25.0 | 2.8 (−19.1 to 22.6) | .79 | 22.8 | 31.7 | 9.0 (−5.0 to 20.4) | .18 |

Δ = difference: percentage or average in experimental high schools minus percentage or average in control high schools. (However, whenever in a baseline subgroup some high schools had no baseline smokers, neither these high schools nor their pairs are included in the (matched-pair) permutation test or in the computation of Δ reported here.) CI = confidence interval. P values (two-sided) were calculated using the group-randomized exact permutation test.

Discussion

The HS intervention, with its proactive identification and recruitment of teen smokers and personalized MI plus CBST telephone counseling protocol, showed evidence of effectiveness for both long- and short-duration smoking abstinence endpoints and for progress toward smoking cessation. This is the first adolescent smoking cessation trial to report statistically significant increases in 6-month prolonged abstinence, as measured 12-months-postintervention-eligibilty, among a large population of adolescent smokers in a nonmedical setting. In addition, treatment effects for the shorter-term duration outcomes of 30- and 7-day abstinence among daily smokers (8.5%, P = .006 and 10.5%, P = .002, respectively) were about three times the treatment effect of 2.9% reported by Sussman et al. (10) in their meta-analysis.

Contributing to the validity of these results are elements of the trial's design and conduct: 1) 50 high schools that were representative of the State of Washington; 2) a large number of smokers (N = 2151); 3) identification of study participants before randomization, ensuring that participant selection was the same in both the control and experimental groups; 4) random assignment of intervention condition by group (high school); 5) explicit consideration of intraclass correlation of endpoint within schools, both in determining sample size necessary to achieve needed statistical power and in analysis method; 6) low (11%) attrition; 7) a prolonged-abstinence (over the 6-month period before the outcome survey completion) outcome measure; 8) conservative determination of cessation, requiring consistent reports of abstinence across multiple outcome measures; 9) implementation of telephone counseling in accordance with an explicit protocol and with documented acceptable fidelity of MI as assessed using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (84); 10) a statistical analysis (permutation inference) based on the randomized assignment of experimental condition, free of modeling or distributional assumptions; and 11) control via stratification of the baseline difference in daily smoking prevalence between experimental and control schools.

The positive results for effectiveness of the HS intervention are important for several reasons. First, the results show that intervention can help teens quit smoking, the number one cause of preventable death in the United States. Second, the results were achieved among older adolescent smokers. Thus, intervention effectiveness was demonstrated during a developmental period when adolescents are at high risk for smoking initiation, escalation, and relapse (3,56,76) and for members of an age group (ages 18–24 years) whose smoking prevalence exceeds 23%, the highest of any age group in the United States for 9 consecutive years (86–88). Third, the telephone counseling component of the intervention used a promising therapeutic model––MI plus CBST—and thus contributes important empirical results to the field of youth smoking cessation. Fourth, the intervention effect was demonstrated in the HS trial among a proactively identified population in which more than 93% of eligible high school juniors completed a baseline survey, and nearly 90% of identified smokers in experimental schools became eligible for the intervention. Thus, this population included smokers who typically would not initiate contact with quitlines or other cessation programs and both daily and less-than-daily smokers. Moreover, because this trial cohort well represented all smokers in 50 high schools, the trial results are generalizable. Finally, 72% (691 out of 948) proactively identified, eligible smokers participated in the intervention and more than half (499 out of 948) completed all of their scheduled counseling calls (54), demonstrating that substantial reach can be attained and that adolescents can be successfully recruited and retained in smoking cessation interventions.

These results support the use of MI in smoking cessation intervention for teens. They are contrary to Hettema's 2005 review (89), which reported a lack of empirical support for the efficacy of MI for smoking cessation, but are consistent with subsequent literature in which one study of “pure” MI (90) and three studies testing MI in combination with other therapeutic modalities (23,30,91) reported statistically significant improvements in adolescent smoking cessation.

Although this two-arm trial cannot determine which components of the intervention were responsible for the positive results, five main features of the HS intervention are worth highlighting as possibly critical to the results obtained: 1) The use of MI—a motivation-enhancing modality that is client centered, nonjudgmental, and respectful of teens’ autonomy, views, and choices—in combination with CBST. 2) Personalization of the intervention so that both the counselor and client focus on the specific needs and issues most relevant to each adolescent smoker. 3) The proactive nature of each phase of intervention: identification of smokers in the larger population, personal outreach to all smokers and selected nonsmokers, and counselor-initiated delivery of the telephone counseling. 4) The trial's inclusion of daily smokers and less-than-daily smokers, as well as nonsmokers, in the intervention, serving to help remove any stigma teens associate with participation in smoking cessation programs. This feature together with personal outreach and counselor-initiated delivery of the telephone counseling seems helpful in recruiting teen smokers who typically would not self-select for intervention. 5) High-quality intervention implementation, including motivated and skilled counselors, use of a detailed protocol, thorough counselor training, and attentive supervision.

Two other randomized controlled trials of teen smoking cessation found statistically significant intervention effects on 30-day or longer smoking abstinence at least 6 months postintervention: Hollis et al. (23) and Pbert et al. (30). These trials had intervention features similar to the HS trial in that they proactively identified and recruited participants within targeted populations: Hollis et al. (23) and Pbert et al. (30) targeted all teens with scheduled appointments at participating pediatric or family practice clinics for recruitment; the HS trial targeted all smokers enrolled as 11th graders in 50 public high schools. All three trials involved both nonsmokers and smokers in their study populations and defined smokers as having smoked in the past 30 days, thus including both daily and nondaily smokers. All three trials tested multicomponent interventions that were personalized to the smoker and that used MI. Hollis et al. (23) tested a transtheoretical model–based intervention that included brief physician advice, an interactive computer program, and individual counseling by health counselors using MI; advice was “highly individualized” to the participant's smoking status and readiness to change. Pbert et al. (30) tested the 5A model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange) (9) combined with MI and behavior change counseling that was delivered by physicians and older peer counselors and tailored to the smoker's current smoking status and responses to key questions. The HS intervention was delivered by telephone counselors, used MI plus skills training, and was personalized to the participant's current smoking status, readiness to change, and stated interests and concerns.

Considering the scarcity of high-quality trials that had positive findings, results from these three trials are important in informing future development of effective teen smoking cessation intervention. Results from the three studies strongly support interventions that are proactive in identifying and recruiting smokers, include nonsmokers as well as smokers, are personalized to the individual smoker, and incorporate motivation enhancement. The effect sizes reported from these three studies were greater than the overall treatment effect size of 2.9% (difference in percent quitting) estimated in a recent meta-analysis of 48 controlled studies of teen smoking cessation, many of which included only those smokers who self-selected for cessation treatment (10). The effect sizes reported in these three studies suggest that with motivation enhancement, smoking cessation intervention can be as effective among unmotivated as among motivated smokers. More important, because proactive approaches are able to reach more smokers, interventions that proactively identify and recruit smokers and address issues of motivation may have a broader public health intervention impact.

It should be emphasized that proactive identification of smokers entails the responsibility to guard confidential information about smoking status against any intervention procedure that could violate confidentiality assurances. For teen smokers, this is especially important because revelation of their smoking status could result in parental discipline or school punishment, which in turn could discourage their participation. In this trial, confidentiality was protected by including selected nonsmokers in the intervention and not revealing smoking status (whether smoker or nonsmoker) when contacting the parent and teen for recruitment.

There are some limitations to consider in evaluating the results of our study. First, because the intervention used more than one component (ie, telephone counseling plus the adjunct Web site and school-based components), integrated use of two therapeutic modalities (MI and CBST), and incorporated multiple strategies to increase reach (eg, personalization of the intervention, telephone delivery), the results from this two-arm trial cannot determine the individual contributions to intervention impact from any specific component or feature. In particular, it is not possible to isolate the effects of the MI from the CBST in this multicomponent intervention. Also, the role of dose (number of calls) in intervention effectiveness cannot be determined, because the number of calls was personalized to the participant's readiness to quit, interest, and response to the intervention.

Second, in spite of the proactive recruitment of teen smokers, nearly 35% of smokers (367 out of 1058) did not complete even one telephone counseling call. Three factors contributed to this result: lack of parental consent for participation of some minor-aged smokers (110 parents either did not reply or declined), failure to reach some eligible smokers despite numerous contact attempts (n = 131), and declines by teen smokers (n = 126). Future trials should consider additional or new methods for overcoming these causes of nonparticipation.

Third, despite efforts to increase enrollment by racial and ethnic minorities, the trial's enrollment of these groups, although reflective of the community populations in the 50 participating schools, was too small (25%) to allow for minority-specific investigations. Nonetheless, the study's emphasis on proactive population-based outreach and recruitment, proactive intervention delivery, and real-time personalization of the intervention to the individual smoker suggest the possibility that this intervention might also work well in racial and ethnic minority populations. Certainly, this is an area for future investigation.

Fourth, the methods used in this trial for proactively identifying smokers may need to be modified and streamlined for dissemination. Although the proactive identification of adolescent smokers via classroom survey with mail and telephone follow-up was successful in our study, and could be replicated in other organizations with access to teens, it may in a dissemination model need to be less intensive with respect to contacting absentees (at a cost of identifying fewer smokers). Regarding parental consent, whereas our method of obtaining consent (using mail and telephone to contact parents before contacting teens) is more effective in reaching parents and obtaining consents than other common methods (eg, contacting eligible students and asking them to obtain written consent from their parents), it is also more costly due to the personnel labor involved. To reduce such costs, two alternatives could be considered: proactively recruiting teen smokers after they reach the age of 18 years, or obtaining an Institutional Review Board waiver of parental consent, appropriate when delivering a minimal risk intervention to older adolescents (40,42,45,92–96).

The current trial's promising findings suggest multiple areas for future research. First, it will be important to replicate these encouraging findings both in general populations of adolescents and in other underserved and high-risk populations. It would also be useful to test a strengthened intervention designed to help additional youth not reached by the current intervention and, possibly, to conduct a multiarm trial to isolate the effects of the MI and CBST intervention components. Also, future trials are needed to further explore treatment-by-gender interactions. Second, additional analyses of mediation and intervention process data may lead to better understanding of how the intervention helped smokers to quit and how it, and counselor training, might be improved to increase intervention effectiveness. Third, continued follow-up of the trial cohort is important to determine to what extent the treatment effects observed at 1 year postintervention reported here persist into adulthood. A finding that effectiveness of an intervention delivered in late adolescence could endure into young adulthood, a developmental period of increased smoking initiation, escalation, and relapse (3,53,56,76), would have important public health implications for reducing smoking prevalence. Fourth, close evaluation of the characteristics of smokers not helped by current intervention strategies will likely be important for further development of interventions with broader effectiveness. Fifth, further research on the understudied population of less-than-daily smokers is warranted to learn more about how to motivate and assist them to quit: They comprise more than 60% of all teen smokers and are at risk for smoking escalation during young adulthood (3,56,76). Indeed, increasing cessation among less-than-daily smokers is an important research goal that, if successful, would contribute to reducing young adult smoking prevalence rates. Finally, further methodological improvement is needed in the rigor of randomized trials of teen smoking cessation (eg, 22,14,11).

In conclusion, the results of the HS trial show that proactive identification and recruitment of adolescents via public high schools can produce a high level of intervention reach, and that delivery of a personalized MI plus CBST counseling intervention via the telephone by well-trained counselors is effective in increasing teen smoking cessation. Both daily and less-than-daily teen smokers participate in and benefit from telephone-based smoking cessation intervention.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA082569 to A.V.P.).

Footnotes

The sponsors had no role in the study design, the collection of the data or its analysis, the interpretation of the results, the preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We acknowledge with deep appreciation the high school seniors (now young adults) who participated in this trial, and their parents, and the leadership, support, and cooperation of the 50 participating Washington high schools. We also acknowledge the advice and guidance of Shu-Hong Zhu, PhD, concerning the trial and intervention design, the contributions of Li Ravicz, PhD, including his provision of motivational interviewing training, and the skillful and conscientious intervention counseling by Melissa M. Phares, MSW; Jennifer Mullane, MEd; Sarah Stivers, BA; and Karin R. Riggs, MSW.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(SS-4):11–14. 37–38, 61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2 vols. 2nd ed. 27. 2B. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. Healthy people, 2010. (27)3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychol. 2000;19(3):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmen TL, Barrett-Connor E, Holmen J, Bjermer L. Adolescent occasional smokers, a target group for smoking cessation? The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, Norway, 1995-1997. Prev Med. 2000;31(6):682–690. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Basen-Engquist K, et al. Transitions out of high school: time of increased cancer risk? [review] Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):694–703. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu S-H, Sun J, Billings SC, Choi WS, Malarcher A. Predictors of smoking cessation in U.S. adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3):202–207. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paavola M, Vartiainen E, Puska P. Smoking cessation between teenage years and adulthood. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(1):49–57. doi: 10.1093/her/16.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanton WR, Lowe JB, Gillespie AM. Adolescents’ experiences of smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;43(1–2):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)84351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sussman S, Sun P, Dent CW. A meta-analysis of teen cigarette smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):549–557. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimshaw GM, Stanton A. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. CD003289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backinger CL, Michaels CN, Jefferson AM, Fagan P, Hurd AL, Grana R. Factors associated with recruitment and retention of youth into smoking cessation intervention studies—a review of the literature. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):359–368. doi: 10.1093/her/cym053. doi:10.1093/her/cym053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skara S, Sussman S. A review of 25 long-term adolescent tobacco and other drug use prevention program evaluations. Prev Med. 2003;37(5):451–474. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backinger CL, McDonald P, Ossip-Klein DJ, et al. Improving the future of youth smoking cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(suppl 2):S170–S184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, et al. Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(4):395–403. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000018470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mermelstein R. Teen smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2003;12(suppl 1):i25–i34. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_1.i25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: USDHHS, PHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sussman S, Dent CW, Lichtman KL. Project EX: outcomes of a teen smoking cessation program. Addict Behav. 2001;26(3):425–438. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St Pierre RW, Shute RE, Jaycox S. Youth helping youth: a behavioral approach to the self-control of smoking. Health Educ. 1983;14(1):28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lotecka L, MacWhinney M. Enhancing decision behavior in high school “smokers. Int J Addict. 1983;18(4):479–490. doi: 10.3109/10826088309033032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curry SJ, Mermelstein RJ, Sporer AK. Therapy for specific problems: youth tobacco cessation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:229–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollis JF, Polen MR, Whitlock EP, et al. Teen reach: outcomes from a randomized, controlled trial of a tobacco reduction program for teens seen in primary medical care. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):981–989. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0981. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Wiehe SE, Rivara FP. Smoking cessation interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(4):363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albrecht SA, Caruthers D, Patrick T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention for pregnant adolescents. Nurs Res. 2006;55(6):402–410. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helstrom A, Hutchison K, Bryan A. Motivational enhancement therapy for high-risk adolescent smokers. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2404–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horn K, Dino G, Hamilton C, Noerachmanto N. Efficacy of an emergency department-based motivational teenage smoking intervention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;1 A08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mermelstein R, Turner L. Web-based support as an adjunct to group-based smoking cessation for adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(suppl 1):S69–S76. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muramoto ML, Leischow SJ, Sherrill D, Matthews E, Strayer LJ. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(11):1068–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pbert L, Flint AJ, Fletcher KE, Young MH, Druker S, DiFranza JR. Effect of a pediatric practice-based smoking prevention and cessation intervention for adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e738–e747. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1029. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun P, Sussman S, Dent CW, Rohrbach LA. One-year follow-up evaluation of Project Towards No Drug Abuse (TND-4) Prev Med. 2008;47(4):438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pbert L, Osganian SK, Gorak D, et al. A school nurse-delivered adolescent smoking cessation intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2006;43(4):312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abrams DB, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer W. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: a combined stepped-care and matching model. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(4):290–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02895291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):688–694. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick LK, Crawford M, Anderson RH, Gittelsohn J, Kingsley B, Upson D. Recruiting adolescents into qualitative tobacco research studies: experiences and lessons learned. J Sch Health. 1999;69(3):95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb07215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pirie PL, Murray DM, Luepker RV. Smoking prevalence in a cohort of adolescents, including absentees, dropouts, and transfers. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(2):176–178. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massey CJ, Dino GA, Horn KA, Lacey-McCracken A, Goldcamp J, Kalsekar I. Recruitment barriers and successes of the American Lung Association's Not-On-Tobacco Program. J Sch Health. 2003;73(2):58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gillespie A, Stanton W, Lowe JB, Hunter B. Feasibility of school-based smoking cessation programs. J Sch Health. 1995;65(10):432–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb08208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balch GI. Exploring perceptions of smoking cessation among high school smokers: input and feedback from focus groups. Prev Med. 1998;27(5, pt 2):A55–A63. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moolchan ET, Mermelstein R. Research on tobacco use among teenagers: ethical challenges. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(6):409–417. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dent CW, Sussman SY, Stacy AW. The impact of a written parental consent policy on estimates from a school-based drug-use survey. Eval Rev. 1997;21(6):698–712. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9702100604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diviak KR, Curry SJ, Emery SL, Mermelstein RJ. Human participants challenges in youth tobacco cessation research: researchers’ perspectives. Ethics Behav. 2004;14(4):321–334. doi: 10.1207/s15327019eb1404_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokorny SB, Jason LA, Schoeny ME, Townsend SM, Curie CJ. Do participation rates change when active consent procedures replace passive consent? Eval Rev. 2001;25(5):567–580. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Severson HH, Ary DV. Sampling bias due to consent procedures with adolescents. Addict Behav. 1983;8(4):433–437. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Severson H, Biglan A. Rationale for the use of passive consent in smoking prevention research: politics, policy and pragmatics. Prev Med. 1989;18(2):267–279. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balch GI, Tworek C, Barker DC, Sasso B, Mermelstein RJ, Giovino GA. Opportunities for youth smoking cessation: findings from a focus group study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):9–17. doi: 10.1080/1462200310001650812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patten CA, Lopez K, Thomas JL, Offord KP, Decker PA. Reported willingness among adolescent nonsmokers to help parents, peers, and others to stop smoking. Prev Med. 2004;39(6):1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leatherdale ST, McDonald PW. What smoking cessation approaches will young smokers use? Addict Behav. 2005;30(8):1614–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amos A, Wiltshire S, Haw S, McNeill A. Ambivalence and uncertainty: experiences of and attitudes towards addiction and smoking cessation in the mid-to-late teens. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(2):181–191. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patten CA, Offord KP, Ames SC, et al. Differences in adolescent smoker and nonsmoker perceptions of strategies that would help an adolescent quit smoking. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):124–133. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacDonald S, Rothwell H, Moore L. Getting it right: designing adolescent-centered smoking cessation services. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1147–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sussman S. Effects of sixty six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tob Induc Dis. 2002;1(1):35–81. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-1-1-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu J, Peterson AV, Kealey KA, Mann SL, Bricker JB, Marek PM. Addressing challenges in adolescent smoking cessation: design and baseline characteristics of the HS group-randomized trial. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kealey KA, Ludman EJ, Mann SL, et al. Overcoming barriers to recruitment and retention in adolescent smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(2):257–270. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanton WR, McGee R. Adolescents’ promotion of nonsmoking and smoking. Addict Behav. 1996;21(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tercyak KP, Rodriguez D, Audrain-McGovern J. High school seniors’ smoking initiation and progression 1 year after graduation. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1397–1398. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gail MH. Eligibility exclusions, losses to follow-up, removal of randomized patients, and uncounted events in cancer clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69(10):1107–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. 1. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34(10):585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bandura A. Self Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research & Practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Donovan DM. Integrating skills training and motivational therapies: implications for the treatment of substance dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;17(1–2):15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kealey KA, Ludman EJ, Marek PM, Mann SL, Bricker JB, Peterson AV. Design and implementation of an effective telephone counseling intervention for adolescent smoking cessation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(20):1393–1405. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychol Bull. 1992;111(1):23–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations [published correction appears in Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(4):603] Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]