Abstract

Background and purpose:

The aim of this study was to assess the relative bioavailability of diazepam after administration of diazepam itself or as a water-soluble prodrug, avizafone, in humans.

Experimental approach:

The study was conducted in an open, randomized, single-dose, three-way, cross-over design. Each subject received intramuscular injections of avizafone (20 mg), diazepam (11.3 mg) or avizafone (20 mg) combined with atropine (2 mg) and pralidoxime (350 mg) using a bi-compartmental auto-injector (AIBC). Plasma concentrations of diazepam were quantified using a validated LC/MS–MS assay, and were analysed by both a non-compartmental approach and by compartmental modelling.

Key results:

The maximum concentration (Cmax) of diazepam after avizafone injection was higher than that obtained after injection of diazepam itself (231 vs. 148 ng·mL−1), while area under the curve (AUC) values were equal. Diazepam concentrations reached their maximal value faster after injection of avizafone. Injection of avizafone with atropine–pralidoxime (AIBC) had no effect on diazepam Cmax and AUC, but the time to Cmax was increased, relative to avizafone injected alone. According to the Akaike criterion, the pharmacokinetics of diazepam after injection as a prodrug was best described as a two-compartment with zero-order absorption model. When atropine and pralidoxime were injected with avizafone, the best pharmacokinetic model was a two-compartment with a first-order absorption model.

Conclusion and implications:

Diazepam had a faster entry to the general circulation and achieved higher Cmax after injection of prodrug than after the parent drug. Administration of avizafone in combination with atropine and pralidoxime by AIBC had no significant effect on diazepam AUC and Cmax.

Keywords: avizafone, diazepam, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, neurotoxic agents, water-soluble prodrug

Introduction

Organophosphates are extensively used around the world as agricultural insecticides and have an important toxicity which is a serious global public health problem, with more than 3 million poisonings and numerous deaths reported per year. They are highly neurotoxic agents and as such have a potential use as weapons. They act by irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that hydrolyses acetylcholine. A rapid accumulation of this neurotransmitter within the synaptic cleft, at muscarinic and nicotinic receptors, causes intense post-synaptic cholinergic stimulation. The toxic signs include hypersecretion, respiratory distress, tremor, seizures/convulsions, coma and death (Hardman and Limbird, 2001; Wetherell et al., 2007). The increased cholinergic activity in the brain most likely induces the initial phase of seizures, whereas sustained seizures are probably linked to increased glutamatergic activity leading to excitotoxic lesions predominantly in piriform cortex, entorhinal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus (Carpentier et al., 1991; Lallement et al., 1992; McDonough et al., 1995; McDonough and Shih, 1997).

Administration of the muscarinic antagonist, atropine, soon after exposure (<5 min) can prevent or stop convulsions, but this antagonist cannot stop them once they are established (McDonough and Shih, 1997; Taysse et al., 2006). Use of glutamatergic antagonists has been partly successful, and non-competitive N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists are able to terminate seizures even if treatment is delayed for 40 min. However, such agents have severe side effects on respiration (Shih, 1990; Shih et al., 1991; McDonough and Shih, 1993; Carpentier et al., 1994). Glutamatergic activity may also be reduced by enhancing the inhibitory GABAergic function. It has been shown that the GABAergic agonist, diazepam, can stop seizures if injected after 5–10 min after their occurrence. Later administration of diazepam has unreliable effects, inasmuch as seizures can recur and only an incomplete neuroprotection is achieved (McDonough and Shih, 1997).

Reactivation of inhibited acetylcholinesterase is considered to be an important element in post-exposure treatment. Bis-pyridinium oximes can reactivate the phosphorylated enzyme if they are administered prior to the change from ‘reactivatable’ to the ‘unreactivatable’ state, a process referred to as ‘ageing’. The oximes, pralidoxime and obidoxime, have been widely used in this type of intoxication (Wetherell et al., 2007).

The use of a benzodiazepine such as diazepam reduces the severity of organophosphate (soman)-induced convulsions, and prevents or reduces subsequent neuropathology (Lipp and Dola, 1980; Hayward et al., 1990; Lallement et al., 2000, 2004; Eddleston et al., 2008). As diazepam is not water soluble, an organic solvent has to be incorporated into the formulation of the triple injection solution. This lack of water solubility limits the value of diazepam given by i.m. injection when pharmacologically effective blood levels are required to be attained rapidly. Moreover, as argued by Maidment and Upshall (1990), the injection solvent used for diazepam is likely to slow the absorption of this drug from the injection site. In order to achieve a rapid onset and to reduce the inter-individual variability, the strategy of developing a prodrug of diazepam was pursued. The water-soluble prodrug, pro-diazepam (avizafone, or lysyl peptido-aminobenzophenone diazepam) has been developed to be one component in an aqueous drug mixture with atropine and pralidoxime for the therapy of nerve agent poisoning. Avizafone in vivo undergoes a rapid hydrolysis by an aminopeptidase to give lysine and diazepam (Maidment and Upshall, 1990; Breton et al., 2006). The half-life of conversion of avizafone to diazepam varies from 2.7 to 4.2 min in monkeys and humans, respectively (Maidment and Upshall, 1990). One study, conducted in primates, showed that the relative bioavailability of diazepam differed when either avizafone (prodrug) or diazepam (parent drug) was injected (Lallement et al., 2000).

However, no study has been published evaluating the relative bioavailability of diazepam after i.m. injection of avizafone, alone or in combination with atropine and pralidoxime, in humans.

The aims of the present study were thus to assess the relative bioavailability of diazepam after the i.m. injection of avizafone in healthy volunteers, and to determine the effect of atropine and pralidoxime on avizafone biotransformation after injection of the combination avizafone–atropine–pralidoxime using the auto-injector under development.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted in an open, randomized, single-dose, three-way, cross-over design with a 3 week wash-out period between the treatments, and was carried out at a single centre: Aster S.A.S. Paris, France.

Twenty healthy adult male volunteers aged between 18 and 45 years (29.7 ± 6.3 years, mean ± SD) were included in the clinical study. All subjects have given written informed consent, and the Ethics Committee has approved the clinical protocol. All volunteers were assessed as healthy based on medical history, clinical examination, blood pressure, electrocardiogram (ECG) and laboratory investigation. There was no individual with either a history or an evidence of hepatic, renal, gastrointestinal and haematological abnormalities, or any acute/chronic disease or drug allergy.

Each subject received the following treatments by i.m. injection: 20 mg of avizafone chlorhydrate (Pharmacie centrale des armées, Orléans, France), 11.3 mg of diazepam (Valium, Roche, France) and 20 mg of avizafone chlorhydrate combined with 2 mg of atropine sulphate and 350 mg of pralidoxime methyl sulphate (Pharmacie centrale des armées) using the bi-compartmental auto-injector (AIBC). This device, AIBC, contained in the first compartment, the three components in a lyophilised form and, in the second compartment, 2.5 mL of water for injection.

Safety assessments included vital signs (supine and standing systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse), a physical examination, a 12-lead ECG and adverse events.

Blood samples were collected before i.m. injection, and 0.0833, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, 120 and 168 h after treatment. The blood samples were centrifuged, and plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until drug assay.

In order to determine diazepam concentrations, protein precipitation was carried out using 150 µL of acetonitrile containing diazepam D5 as internal standard. The samples were vortex-mixed and then centrifuged. The supernatants were transferred to micro-vials, and 10 µL was injected into the chromatographic system. The samples were analysed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using a C-8 X-Terra column (Waters, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France) maintained at 40°C. The mobile phase was nebulized using an electrospray source, and the ionized compounds were detected using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Abbara et al., 2008).

Calibration curves were linear over the range 1–500 ng·mL−1, with regression coefficient R2≥ 0.99. Based on quality control samples, the overall relative standard deviation was less than 12%. The overall relative error was less than 10%. The lower limit of quantification was 1 ng·mL−1.

Data analysis

Non-compartmental approach

The non-compartmental model independent analysis was performed using WinNonLin Pro v.4.1 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). For each subject, data corresponding to three treatments were analysed separately. Data were used to estimate individual maximal concentration (Cmax) and time necessary to reach maximal concentration (tmax). In addition, for each treatment the elimination rate constant (Ke), and the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) were estimated. Ke was estimated as the slope of the log-linear terminal portion of the plasma concentration versus time curve, determined using unweighted linear least square regression analysis. The best number of concentrations was chosen as that giving the highest coefficient of determination, as recommended. AUC was computed from 0 to 168 h using the log-linear trapezoidal method and extrapolated to infinity using the equation AUC0–∞= AUC0–t+Clast/Ke, where Clast is the last quantified concentration above the lower limit of quantification.

Additionally, from these estimated parameters, terminal elimination half-life after each treatment was derived as t1/2= ln2/Ke.

Two parameters, AUC and Cmax, were then compared using the two one-sided t-test approach, which is also referred to as the confidence interval approach or Schuirmann test.

The 90% confidence limits are estimated for the sample means. The interval estimate is based on a Student's distribution of data. In this test, a 90% confidence interval about the ratio of pharmacokinetic parameter means of the two drug products must be within ±20% for measurement of the rate (Cmax) and extent of drug bioavailability.

This approach was performed on the log-transformed AUC and Cmax values. The tmax were then compared using a non-parametric test (Wilcoxon test).

Compartmental modelling approach

Pharmacokinetic models used

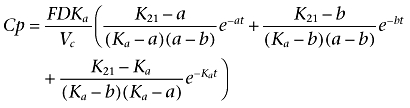

The models compared in this study are standard WinNonLin models. In order to describe the absorption after the i.m. injection, two absorption kinetic models were compared. First, the two-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination rates described by the equation:

|

(1) |

where Ka is the absorption rate constant; D is the dose administered by i.m. injection; F is the fraction of drug absorbed; a and b are constants that depend solely on K12, K21 (transfer constants between compartments 1 and 2) and Ke (elimination constant); and Vc is the volume of distribution in the central compartment.

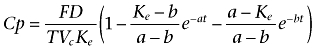

The second model was a two-compartment model with zero-order absorption rate and first-order elimination rate, and was described by the equation:

For t≤T

|

(2) |

and for t > T

|

(3) |

where T represents the duration of absorption; D is the dose administered by i.m. injection; F is the fraction of drug absorbed; a and b are constants that depend solely on K12, K21 (transfer constants between compartments 1 and 2) and Ke (elimination constant); and Vc is the volume of distribution in the central compartment.

Method of estimation

The initial estimates of the pharmacokinetic parameters were computed by WinNonLin using curve stripping.

The pharmacokinetic parameters were Vc, Ke, K12, K21 and an absorption parameter Ka in the case of first-order absorption. In the case of zero-order absorption, T was fixed and determined as time necessary to reach the maximal concentration and that for each subject and each treatment individually.

From these parameters, several derived pharmacokinetic parameters were computed: AUC, time needed to reach maximal concentration tmax and maximal concentration Cmax. For each concentration, an additional error was assumed arising from a zero mean Gaussian distribution, with a heteroscedastic variance. Errors on two different concentrations were assumed to be uncorrelated. The error included: error of the analytical method and error inherent to the pharmacokinetic model. The Gauss–Newton method with Levenberg modification was used to provide the ‘least square’ estimates. Data were weighted using a constant coefficient of variation error model based on model-predicted plasma concentration 1/ŷ2.

Comparison of models

The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to identify the best combination of models, because the first-order and the zero-order absorption models are not nested. This criterion can be viewed as the sum of a measure of the goodness of fit, and of a penalty function proportional to the number of estimated parameters in the model. For each combination of models, the criterion for all subjects was computed. The combination of models with the smallest AIC is the most adequate according to the parsimony principle.

Results

Non-compartmental approach

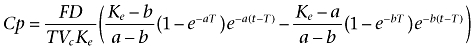

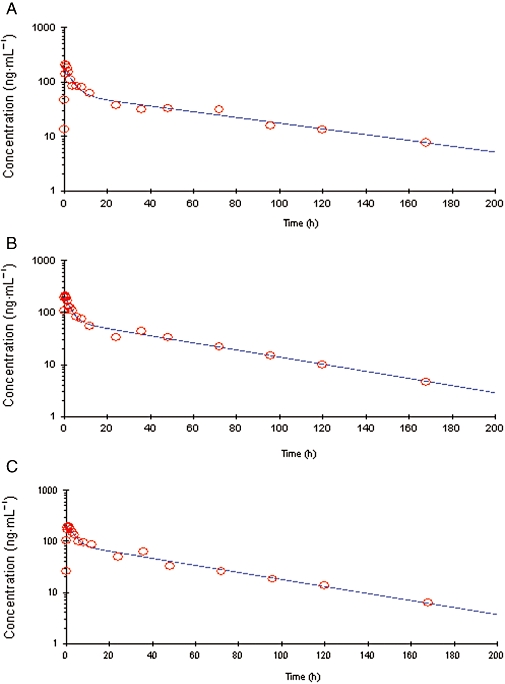

Plasma diazepam concentrations were quantified after i.m. administration of three treatments: avizafone alone, diazepam alone and avizafone with atropine and pralidoxime using the AIBC device with a 3 week wash-out period. The mean plasma concentrations of diazepam, obtained after the three different treatments, are plotted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean pharmacokinetic profile of diazepam after the intramuscular administration of avizafone alone (A), diazepam alone (B) and avizafone with atropine and pralidoxime using the bi-compartmental auto-injector (C).

Table 1 shows the main and derived pharmacokinetic parameters of diazepam obtained after a non-compartmental analysis of the data for the three treatments.

Table 1.

Estimated and derived pharmacokinetic parameters of diazepam obtained with the non-compartmental approach

|

Avizafone |

Diazepam |

AIBC |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| AUC0–t (h ng·mL−1) | 5851 (2086) | 5485 (1856) | 5265 (1802) |

| tmax (h)a | 0.75 (0.5–1)b | 1.5 (0.5–96)b | 1 (0.5–2)b |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 231 (60) | 148 (91) | 203 (54) |

| Ke (h−1) | 0.02 (0.013) | 0.017 (0.009) | 0.018 (0.009) |

| t1/2 (h) | 50.1 (35.8) | 54.4 (38.0) | 55.5 (50.8) |

| Relative bioavailabilitya,c | 1.05 (0.85–1.39)b | 1 | 0.95 (0.78–1.23)b |

Median.

Range.

Diazepam is reference treatment.

AIBC, avizafone with atropine–pralidoxime in bi-compartmental auto-injector; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximal concentration; Ke, elimination constant; t1/2, elimination half-life; tmax, time to reach maximal concentration.

The results regarding the relative bioavailability of diazepam after the three treatments are summarized in Table 2. The Cmax of diazepam liberated from avizafone was significantly greater than that obtained after the administration of an equimolar dose of diazepam, while the AUC values were very similar. Diazepam concentrations reached their maximal value earlier (shorter tmax) when it was injected as a prodrug (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Relative diazepam bioavailability after the three treatments

| Parameters |

Geometric means |

Ratiob | P | 90% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avizafone | Diazepam | ||||

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 223 | 118 | 1.89 | – | 1.53–2.35d |

| AUC0 −t (h ng·mL−1) | 5584 | 5224 | 1.07 | – | 1.01–1.13 |

| tmax (h)a | 0.75 | 1.5 | – | <0.001 | – |

| Parameters |

Geometric means |

Ratioc | P | 90% CI | |

| Avizafone | AIBC | ||||

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 223 | 197 | 1.136 | – | 1.043–1.238 |

| AUC0 −t (h ng·mL−1) | 5584 | 5025 | 1.111 | – | 1.075–1.148 |

| tmax (h)a | 0.75 | 1 | – | 0.008 | – |

Median.

Avizafone/Diazepam.

Avizafone/AIBC.

Bioequivalence criteria not met.

AIBC, avizafone with atropine–pralidoxime in bi-compartmental auto-injector; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximal concentration; tmax, time to reach maximal concentration.

The co-administration of atropine and pralidoxime with avizafone seemed to decrease diazepam Cmax and its AUC. The application of Schuirmann test showed that, for these two parameters, the 90% confidence interval was still in the range 0.80–1.25. Diazepam concentrations reached their maximal value earlier when avizafone was injected alone, compared to AIBC injection (P= 0.008).

Compartmental modelling approach

On a log scale, data appeared to exhibit a bi-exponential decline and that describes the sum of two first-order processes: distribution and elimination. Hence, two-compartment open models were studied in order to describe the pharmacokinetics of diazepam after the three treatments.

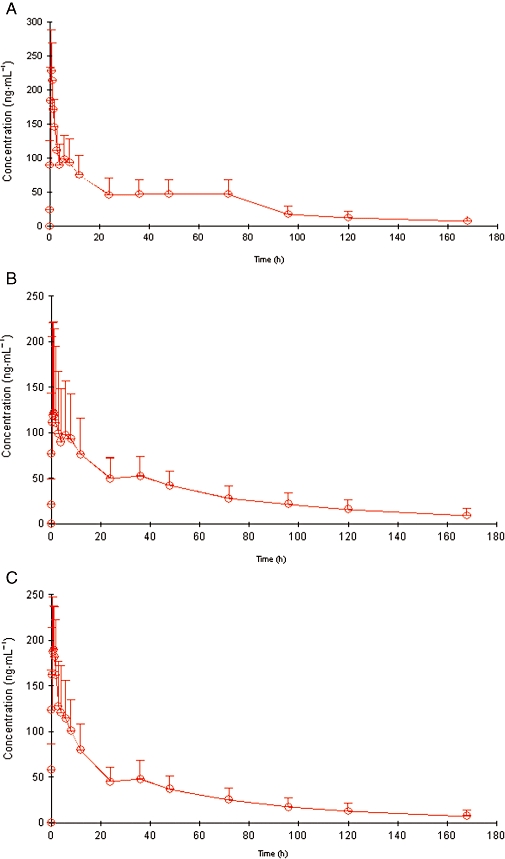

For each combination of models, individual fittings of data after the three treatments were obtained. Figure 2 shows the pharmacokinetic curve fitted by the model for a typical subject. In this figure, the comparison between observed and predicted concentrations confirmed the bi-exponential elimination suggested by the data.

Figure 2.

Semi-logarithmic plot of time course of plasma concentrations of diazepam in a typical subject, after intramuscular injection of avizafone alone (A), diazepam alone (B) and avizafone with atropine and pralidoxime using the bi-compartmental auto-injector (AIBC) (C). Solid lines represent the pharmacokinetic curve predicted by the two-compartment model with a zero-order absorption (for avizafone), or a first-order absorption (for diazepam and AIBC).

After the administration of avizafone alone, diazepam peak concentrations were better predicted by a zero-order absorption model than by a first-order absorption model. However, when avizafone was administered with atropine and pralidoxime, the diazepam peak concentrations were better predicted by a first-order absorption model. This model also described, with a good fit, the diazepam peak concentrations after i.m. administration of diazepam.

These graphical results were confirmed by the AIC for all subjects and are summarized in Table 3, and that for both absorption orders after the three treatments. Thus, the pharmacokinetics of diazepam liberation from its prodrug could be described by a two-compartment open model with zero-order absorption, but when the prodrug was administered with atropine and pralidoxime, the pharmacokinetics were better described by a two-compartment open model with first-order absorption.

Table 3.

Values of Akaike information criterion for all subjects and for the two absorption models studied

| Avizafone | Diazepam | AIBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-order absorption | 368.8 | −28.4 | −111.3 |

| Zero-order absorption | 243.6 | 17.9 | 149.3 |

AIBC, avizafone with atropine–pralidoxime in bi-compartmental auto-injector.

For the chosen models, no trend was noticed in the plots of standardized residuals against predicted concentrations or against time. The pharmacokinetic parameters estimated with the iterative reweighted least square method are summarized in Table 4. The standard errors of individual estimates were also obtained, except for the time of absorption T in the model with zero-order absorption, which was fixed and determined as the tmax estimated using the non-compartmental approach.

Table 4.

Estimated and derived pharmacokinetic parameters of diazepam obtained with the compartmental modelling approach

|

Avizafone |

Diazepam |

AIBC |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Vc (L) | 41.60 (11.87) | 60.19 (46.87) | 51.65 (15.68) |

| Ka (h−1) | – | 2.53 (1.68) | 3.69 (1.63) |

| Ke (h−1) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.01) |

| K12 (h−1) | 0.71 (0.62) | 0.25 (0.26) | 0.23 (0.23) |

| K21(h−1) | 0.38 (0.19) | 0.20 (0.13) | 0.14 (0.09) |

| AUC (h ng·mL−1) | 6900 (2885) | 6355 (2639) | 5975 (2278) |

| tmax (h) | – | 2.53 (3.67) | 0.91 (0.26) |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 235 (49) | 172 (72) | 187 (0.51) |

AIBC, avizafone with atropine–pralidoxime in bi-compartmental auto-injector; AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximal concentration; K12, K21, transfer constants between compartments 1 and 2; Ka, absorption constant; Ke, elimination constant; tmax, time to reach maximal concentration; Vc, volume of distribution of central compartment.

From the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters, AUC and Cmax were derived for the three treatments, while tmax was derived only for two treatments: diazepam and AIBC (avizafone in combination with atropine and pralidoxime) (Table 4). The results obtained after this analysis appear to be in agreement with those obtained after the non-compartmental analysis. They confirmed the faster entry of diazepam into the general circulation and its higher maximal concentration after avizafone injection, compared to those after injection of diazepam itself.

Discussion

This was the first study in humans aiming to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters of the hydrolysis of avizafone, a prodrug, into diazepam, the parent drug, after i.m. administration either alone or in combination with atropine and pralidoxime.

Therefore, a non-compartmental approach and a compartmental modelling analysis were performed. As the three treatments were given within a 3 week period, inter-occasion variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters has been taken into account, with the assumption that plasma clearance remains constant (Rowland, 1980). In a non-compartmental approach, kinetics after different treatments are always analysed separately, and individual pharmacokinetic parameters are estimated for each period of treatment. In a compartmental modelling approach, inter-occasion variability can be modelled using a random effect model. In the compartmental modelling part of this study, in order to take into account the inter-occasion variability without modelling it, the three kinetics after each treatment administration were modelled separately. As mentioned earlier, the non-compartmental analysis followed by the confidence interval approach (FDA 2001), showed that the appearance of diazepam in plasma was achieved earlier and at higher concentrations after avizafone i.m. administration, than after the i.m. administration of an equimolar dose of diazepam, while the total exposure to diazepam, measured by AUC, was the same when diazepam was injected directly or as a prodrug.

High inter-individual variability was observed for absorption parameters (Cmax and tmax) after i.m. injection of diazepam. This variability could be explained by the use of an organic injection solvent with diazepam. This solvent slows diazepam absorption which results in a large variability in plasma concentrations and distribution of diazepam (Maidment and Upshall, 1990). Hence, the coefficients of variation for the pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax and tmax) of diazepam were higher after diazepam injection than after avizafone injection.

Lallement et al. (2000) related the low efficacy of avizafone in stopping seizures to the relatively reduced total diazepam exposure after the prodrug administration. In their study, the relative bioavailability of diazepam liberated from avizafone, when injected in combination with atropine and pralidoxime, was found to be 62–66% of that after i.m. injection of diazepam alone. The pharmacokinetic data obtained from two monkeys showed that diazepam plasma levels were achieved faster and declined more rapidly after the prodrug than after the parent drug. These results were in agreement with previous data obtained in guinea pigs or rhesus monkeys, and were explained by either: (i) an incomplete conversion of avizafone to diazepam; or (ii) an excretion of avizafone itself before conversion to diazepam (Maidment and Upshall, 1990; Lallement et al., 2000; Breton et al., 2006). These data demonstrated that, in combination with atropine and pralidoxime, the prodrug needed to be injected at higher dose than diazepam (1 µmol avizafone vs. 0.7 µmol) to obtain similar neuroprotection, as neuroprotection was correlated with the total exposure to diazepam (Carpentier et al., 1994). However, there were no human data published, in agreement with these pre-clinical studies.

Hence, in our study, we chose to compare the pharmacokinetics of diazepam after the injection of avizafone alone and diazepam alone at the same molar dose. The present results are not in agreement with the results from the pre-clinical studies. Indeed, clinical data showed that after avizafone injection, the AUC of diazepam was equivalent to that obtained after the injection of the same dose, on a molar basis, of diazepam alone, without modification of diazepam elimination half-life. Meanwhile, the Cmax for diazepam was twofold higher and obtained faster after the injection of the prodrug. Thus, this analysis demonstrated that the selected avizafone dose was able to provide pharmacologically active plasma concentrations of diazepam and to achieve the Cmax more rapidly. However,whether such clinical results would still be achieved after injection of avizafone or diazepam in combination with atropine and pralidoxime remains to be determined.

The compartmental modelling analysis was achieved using a non-linear least square method. The basic problem in this method is finding the values of θ, the model parameter, which minimizes the residual sum of squares which is essentially a question of optimization. A constant coefficient of variation error model was chosen, and the iteratively reweighted least square method has been used. In this method, the first estimation of the parameter is achieved by a regression, and this estimation is weighted and then re-estimated by the weighted least square method (Bonate, 2006).

The error is a combination of assay error and error inherent to the pharmacokinetic model. Quality control samples used during diazepam quantification in subject samples showed that a constant coefficient of variation error model was appropriate for assay error. It was assumed that such a model could also well describe error due to the pharmacokinetic model. Actually, it is reasonable to assume that this kind of error is more important during the absorption and the distribution phases rather at the end of the kinetics. Otherwise, there was no reason to assume that the variance parameters could be different among the subjects. The AIC was used to select the combination of models that included the best absorption model, in addition to the plots of predicted and observed concentration against time. Ludden et al. (1994) showed that this criterion was reliable in the evaluation of pharmacokinetic equations.

The compartmental analysis showed that the pharmacokinetics of diazepam administered intramuscularly followed a two-compartment model with first-order absorption. This analysis confirmed the large inter-individual variability in diazepam pharmacokinetic parameters, which was already noticed after the non-compartmental analysis, mainly during the absorption period. When diazepam was injected intramuscularly as a prodrug, the absorption process for diazepam seemed to be fast and achieved by zero-order rate process, while its distribution and elimination were comparable to those noticed after its i.m. injection as a parent drug. These results could explain those obtained after the relative bioavailability analysis concerning the two pharmacokinetic parameters, Cmax and tmax, estimated by the non-compartmental analysis. After i.m. injection, the delivery of the injected drug into the general circulation is achieved according to rapid absorption processes, depending upon the rate of blood flow to the injection site, which could explain the observation of zero-order absorption processes (Hardman and Limbird, 2001).

When avizafone is administered with atropine and pralidoxime using the AIBC device under development, a two-compartment model with first-order absorption was identified as the best model fitting the pharmacokinetics of diazepam liberated from avizafone. For this treatment (AIBC), a delay in the absorption of diazepam was noted, and this was accompanied by a shift of the best mathematical model fitting this process from zero-order to first-order. This delayed absorption could be due to either a delay in the conversion of avizafone (partially or totally) or a modification in diazepam absorption profile, without altering the hydrolysis of avizafone. Neither of the other two compounds in the AIBC, atropine or pralidoxime, exhibits pharmacological properties, suggesting inhibition of aminopeptidase activity which might modify avizafone hydrolysis. Nevertheless, atropine when administered in clinical doses to induce anti-cholinergic effects, counteracts the peripheral effects of acetylcholine, that is, vasodilatation, leading to modification of blood flow rate at the site of injection (Hardman and Limbird, 2001). Hence, this pharmacological property could explain the delay in the absorption process for diazepam, when the prodrug was given in combination with atropine and pralidoxime.

In summary, non-compartmental analysis followed by the confidence interval approach disclosed differences between pharmacokinetic parameters regarding the bioavailability (AUC and Cmax), while the compartmental approach allowed the characterization of the best absorption model and provided several pharmacokinetic parameters that could not be obtained with a model-independent analysis. Our results, overall, provide a better understanding of some of the processes involved in the biotransformation of avizafone into diazepam. The analyses showed that avizafone is equivalent to diazepam in terms of AUC, but provided a higher Cmax. Administration of avizafone in combination with atropine and pralidoxime by AIBC had no significant effect on diazepam AUC and Cmax. Avizafone is expected to achieve a rapid onset of action in vivo due to its shorter tmax.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AIBC

bi-compartmental auto-injector

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- AUC

area under the curve

- Cmax

maximal concentration

- K12

K21 transfer constants between compartments 1 and 2

- Ka

absorption constant

- Ke

elimination constant

- tmax

time to reach maximal concentration

- Vz

distribution volume

Conflict of interest

The study had been sponsored by the Service de Santé des Armées, France. J.M.R., G.L., I.B. and P.C. are employees of the Service de Santé des Armées, France.

References

- Abbara C, Bardot I, Cailleux A, Lallement G, Le Bouil A, Turcant A, et al. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) method for the simultaneous determination of diazepam, atropine and pralidoxime in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;847:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonate P. Pharmacokinetic–Pharmacodynamic Modeling and Simulation. New York: Springer; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton D, Buret D, Mendes-Oustric AC, Chaimbault P, Lafosse M, Clair P. LC-UV and LC–MS evaluation of stress degradation behaviour of avizafone. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;41:1274–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier P, Lambrinidis M, Blanchet G. Early dendritic changes in hippocampal pyramidal neurones (field CA1) of rats subjected to acute soman intoxication: a light microscopic study. Brain Res. 1991;541:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier P, Foquin-Tarricone A, Bodjarian N, Rondouin G, Lerner-Natoli M, Kamenka JM, et al. Anticonvulsant and antilethal effects of the phencyclidine derivative TCP in soman poisoning. Neurotoxicology. 1994;15:837–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Buckley NA, Eyer P, Dawson AH. Management of acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning. Lancet. 2008;371:597–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA. Statistical Approaches to Establishing Bioequivalence. Rockville: Food and Drug Administration; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Limbird LE. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward IJ, Wall HG, Jaax NK, Wade JV, Marlow DD, Nold JB. Decreased brain pathology in organophosphate-exposed rhesus monkeys following benzodiazepine therapy. J Neurol Sci. 1990;98:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90185-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallement G, Carpentier P, Collet A, Baubichon D, Pernot-Marino I, Blanchet G. Extracellular acetylcholine changes in rat limbic structures during soman-induced seizures. Neurotoxicology. 1992;13:557–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallement G, Renault F, Baubichon D, Peoc'h M, Burckhart MF, Galonnier M, et al. Compared efficacy of diazepam or avizafone to prevent soman-induced electroencephalographic disturbances and neuropathology in primates: relationship to plasmatic benzodiazepine pharmacokinetics. Arch Toxicol. 2000;74:480–486. doi: 10.1007/s002040000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallement G, Masqueliez C, Baubichon D, Cassegrain N, Renaudeau P, Clair P. Protection against soman-induced lethality of antidote combination atropine–pralidoxime–prodiazepam packaged as a freeze-dried form. J Med Chem Def. 2004;2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lipp J, Dola T. Comparison of the efficacy of HS-6 versus HI-6 when combined with atropine, pyridostigmine and clonazepam for soman poisoning in the monkey. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1980;246:138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludden TM, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. Comparison of the Akaike information criterion, the Schwarz criterion and the F test as guides to model selection. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1994;22:431–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02353864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JH, Jr, Shih TM. Pharmacological modulation of soman-induced seizures. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1993;17:203–215. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JH, Jr, Shih TM. Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent-induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:559–579. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JH, Jr, Dochterman LW, Smith CD, Shih TM. Protection against nerve agent-induced neuropathology, but not cardiac pathology, is associated with the anticonvulsant action of drug treatment. Neurotoxicology. 1995;16:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment MP, Upshall DG. Pharmacokinetics of the conversion of a peptido-aminobenzophenone prodrug of diazepam in guinea pigs and rhesus monkey. J Biopharm Sci. 1990;1:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland M. Towards Better Safety of Drugs and Pharmaceutical Products. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-Holland; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Shih TM. Anticonvulsant effects of diazepam and MK-801 in soman poisoning. Epilepsy Res. 1990;7:105–116. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90095-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih TM, Koviak TA, Capacio BR. Anticonvulsants for poisoning by the organophosphorus compound soman: pharmacological mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1991;15:349–362. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taysse L, Daulon S, Delamanche S, Bellier B, Breton P. Protection against soman-induced neuropathology and respiratory failure: a comparison of the efficacy of diazepam and avizafone in guinea pig. Toxicology. 2006;225:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell J, Price M, Mumford H, Armstrong S, Scott L. Development of next generation medical countermeasures to nerve agent poisoning. Toxicology. 2007;233:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]