Abstract

N-myristoylation is a common form of co-translational protein fatty acylation resulting from the attachment of myristate to a required N-terminal glycine residue.1,2 We show that aberrantly acquired N-myristoylation of SHOC2, a leucine-rich repeat-containing protein that positively modulates RAS-MAPK signal flow,3–6 underlies a clinically distinctive condition of the neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous disorders family. Twenty-five subjects with a relatively consistent phenotype previously termed Noonan-like syndrome with loose anagen hair [OMIM 607721]7 shared the 4A>G missense change (Ser2Gly) in SHOC2 that introduces an N-myristoylation site, resulting in aberrant targeting of SHOC2 to the plasma membrane and impaired translocation to the nucleus upon growth factor stimulation. Expression of SHOC2S2G in vitro enhanced MAPK activation in a cell type-specific fashion. Induction of SHOC2S2G in Caenorhabditis elegans engendered protruding vulva, a neomorphic phenotype previously associated with aberrant signaling. These results document the first example of an acquired N-terminal lipid modification of a protein causing human disease.

Dysregulation of the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway has recently been recognized as the molecular cause underlying a group of clinically related developmental disorders with features including reduced growth, facial dysmorphism, cardiac defects, ectodermal anomalies, variable cognitive deficits and susceptibility to certain malignancies8,9. These Mendelian traits are caused by mutations in genes encoding RAS proteins (KRAS and HRAS), downstream transducers (RAF1, BRAF, MEK1 and MEK2), or pathway regulators (PTPN11, SOS1, NF1 and SPRED1). For NS (NS), the commonest of these disorders, mutations are observed in several of these, constituting approximately 70% of cases.

To rationalize further candidate gene approaches to NS gene discovery, we used a systems biology approach based on in silico protein network analysis. By applying a graph theory algorithm on a filtered consolidated human interactome, we derived a subnetwork of proteins generated from an integrated network of mammalian protein interaction databases and cell-signaling network datasets by seeding with the known RAS/MAPK mutant proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1a online). To identify potential NS disease genes, Z scores were computed using a binomial proportions test, ranking the significance of the intermediate nodes within the subnetwork based on their connections to the seed proteins10 (Supplementary Table 1 online). Resequencing of coding exons for the best candidate, SHOC2, in a NS cohort including 96 individuals who were negative for mutations in known disease genes and opportunely selected to represent the wide phenotypic spectrum characterizing this disorder revealed an A-to-G transition at position 4 of the gene, predicting the Ser2Gly amino acid substitution (S2G), in four unrelated individuals (Supplementary Fig. 1b online). All cases were sporadic, and genotyping of parental DNAs available for three of the four subjects documented the absence of the sequence variant in the parents and confirmed paternity in each family, providing evidence that the change was a de novo mutation associated with the disease. For these subjects, DNAs from several tissues were available and all harboured the S2G mutation, providing evidence that the defect was inherited through the germline. We then analyzed SHOC2 in a cohort of 410 mutation-negative subjects with NS or a related phenotype. We observed 21 with the 4A>G missense change and proved that mutations were de novo in twelve families from which parental DNAs were available. No additional disease-associated SHOC2 sequence variant was identified in the analyzed cohort, strongly suggesting a specific pathogenetic role for the S2G amino acid substitution.

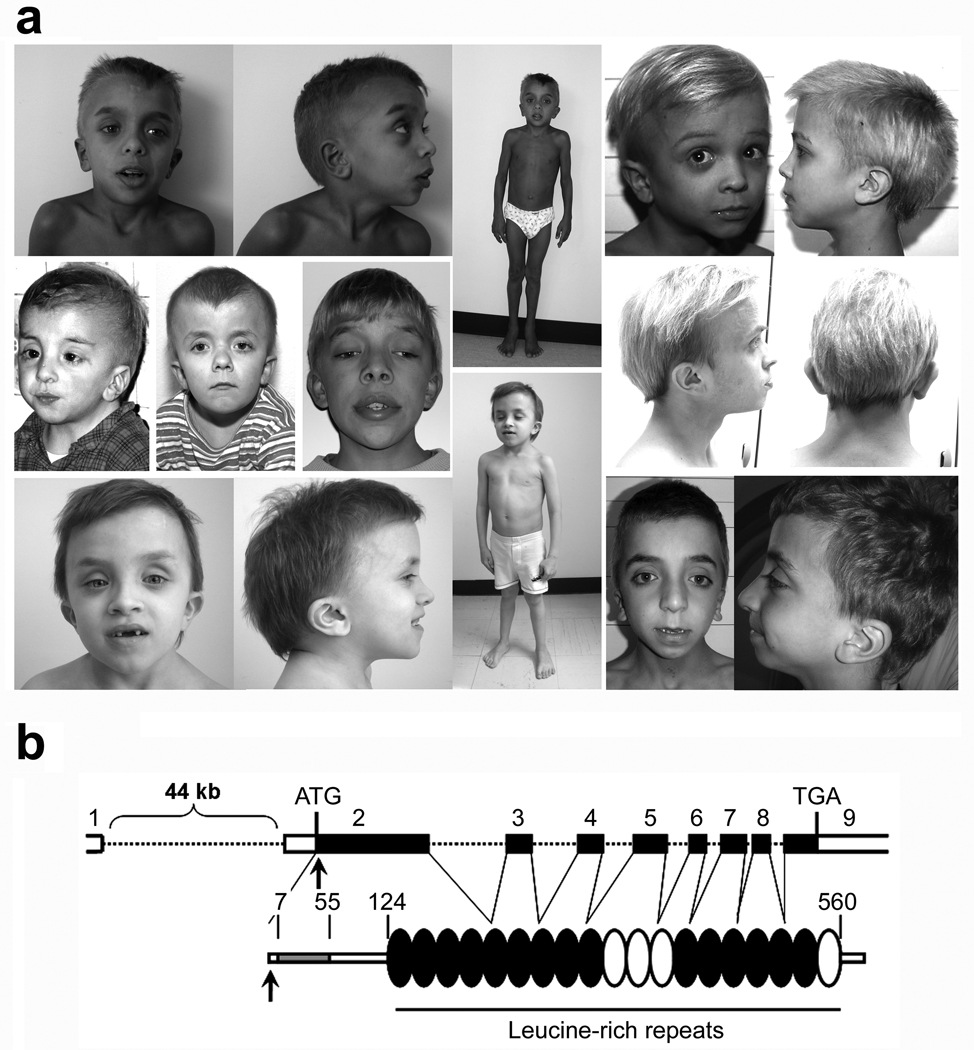

Review of the clinical features of the SHOC2 mutation-positive individuals revealed a consistent phenotype, previously termed Noonan-like syndrome with loose anagen hair 7. While their facial features seemed typical for NS (Fig. 1a), phenotype analysis of these subjects was notable for the observation that they exhibited reduced growth, which was frequently associated with proven GH deficiency, cognitive deficits, distinctive hyperactive behaviour that improved with age in most subjects, and hair anomalies including easily pluckable, sparse, thin, slow growing hair. In twelve subjects, a diagnosis of loose anagen hair was confirmed by microscopic examination of pulled hairs. Most of them also exhibited darkly pigmented skin with eczema or ichthyosis. Cardiac anomalies were observed in the majority of the cases, with dysplasia of the mitral valve and septal defects significantly overrepresented compared with the general NS population. The voice was characteristically hypernasal. Of note, the referring pediatricians felt that several of these subjects had features suggestive of Costello syndrome or cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, as newborns or young infants. Overall, these subjects appeared to share a phenotype that was characterized by an unusual combination of features observed in disorders of the neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous disorders family (Supplementary Table 2 online).

Figure 1. The germline 4A>G mutation in the SHOC2 gene underlies a distinctive phenotype of the neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous syndrome family.

(a) Representative phenotypic features of affected subjects carrying the SHOC2 mutation. Common features include macrocephaly, high forehead, hypertelorism, palpebral ptosis, low-set/posteriorly rotated ears, short and webbed neck, and pectus anomalies. Affected subjects also exhibited easily pluckable, sparse, thin, slow-growing hair. (b) SHOC2 genomic organization and protein structure. The coding exons are shown at the top as numbered filled boxes. Intronic regions are represented by dotted lines. SHOC2’s motifs comprise an N-terminal lysine-rich region (grey coloured; Prosite motif score = 8.8) followed by 19 leucine-rich repeats (Pfam hits with an E-value <0.5 are black coloured, while those with an E-value >1 are represented in white). Numbers above the domain structure indicate the amino acid boundaries of those domains.

SHOC2 is a widely expressed protein composed almost entirely by leucine-rich repeats (LRR) with a lysine-rich sequence at the N-terminus (Fig. 1b). In C. elegans, where SHOC2/SUR-8/SOC-2 was discovered, the protein acts as a positive modulator of the signal transduction elicited by EGL-15 and LET-23, and mediated by LET-60, homologues of vertebrate FGFR, EGFR and RAS family members, respectively3,4. Since LRRs can provide a structural framework for protein-protein interactions, SHOC2 is believed to function as a scaffold linking RAS to downstream signal transducers4–6. Based on the N-terminal position of the S2G substitution, we hypothesized that co-translational processing might be perturbed in the mutant protein, making it a substrate for the N-myristoyltransferase (NMT). N-terminal myristoylation is an irreversible modification generally occurring during protein synthesis, in which myristate, a 14-carbon saturated fatty acid, is covalently added to an N-terminal glycine residues after excision of the initiator methionine residue by methionylaminopeptidase1,2. Glycine at codon 2 is absolutely required, small uncharged residues at positions 3 and 6 are generally needed, and basic residues at positions 7–9 are preferred11. Save the presence of Ser at position 2, the N-terminal sequence of the SHOC2 satisfied those consensus rules, and in silico analysis predicted myristoylation of the SHOC2S2G mutant with high confidence. To verify this, the myristoylation status of wild type and mutant SHOC2 proteins transiently expressed in Cos-1 cells was evaluated (Fig. 2a). SHOC2S2G incorporated [3H]-myristic acid, while the wild type protein and the disease-unrelated SHOC2S2A did not.

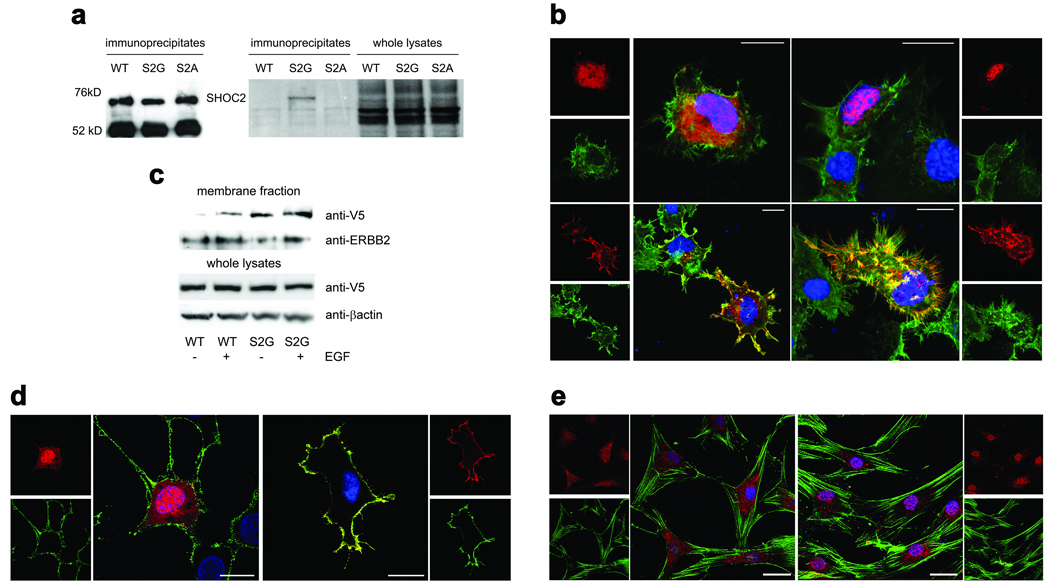

Figure 2. The disease-causing 4A>G change in SHOC2 promotes protein myristoylation and cell membrane targeting.

(a) [3H]myristic acid incorporation (middle) occurs in SHOC2S2G but not in SHOC2wt or SHOC2S2A. Equivalent levels of SHOC2 proteins in immunoprecipitates (left) and [3H]myristic acid incorporation in cells (right) are shown. (b) SHOC2wt is uniformly present in the cytoplasm and nucleus in starved Cos-1 cells (upper left) and is restricted to the nucleus following EGF stimulation (upper right), while SHOC2S2G is targeted to the cell membrane basally (lower left) and after stimulation (lower right). Confocal microscopy visualized SHOC2 (anti-V5 monoclonal antibody, then Alexa Fluor-594 goat anti-mouse antibody; red), actin cytoskeleton (Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin; green) and nuclei (DAPI; blue). (c) Cell fractioning assay documenting preferential membrane targeting of SHOC2S2G. Transiently transfected cells were serum-starved or stimulated with EGF, and lysates were fractionated to separate membrane-associated proteins. ERBB2 is shown to demonstrate equivalent fractionation efficiency, while anti-V5 blot from cell lysates show equivalent transfection efficiency. (d) Co-localization of V5-tagged SHOC2S2G and ganglioside M1 to the plasma membrane in Cos-1 cells. Subcellular localization of V5-tagged wild type SHOC2 (left) and V5-tagged SHOC2S2G (right) is shown. Ganglioside M1 was detected by using the Vybrant Lipid Raft Labeling kit (green). SHOC2 proteins and nuclei are visualized as reported above. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. (e) Subcellular localization of the endogenous SHOC2wt protein in primary skin fibroblasts, basally (left) and following stimulation (right). Confocal microscopy was performed using an anti-SHOC2 polyclonal antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit antibody (red), while actin cytoskeleton was detected by Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin (green). All images represent single optical sections representative of > 50 transfected cells observed in each experiment. Bars indicate 20 µm (b and d) or 40 µm (e).

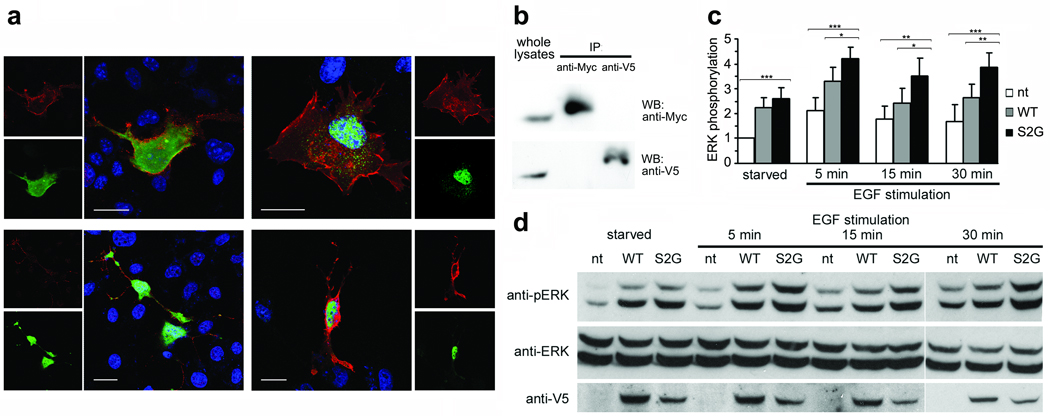

N-myristoylation facilitates anchoring of proteins to intracellular membranes. To explore whether it conferred membrane targeting to mutant SHOC2, the subcellular localization of V5-tagged SHOC2 proteins was analyzed in Cos-1 cells (Fig. 2b,d). Confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis documented that SHOC2wt was uniformly distributed in the cytoplasm and nucleus in starved cells but was restricted to the nucleus following EGF stimulation, implying an unexpected role for this protein in signal transduction. In contrast, SHOC2S2G was specifically targeted to the cell membrane in both states. This aberrant localization of SHOC2S2G was confirmed in 293T and Neuro2A cell lines and using a Myc-tagged protein (data not shown), as well as by cell fractionation (Fig. 2c). Growth factor-stimulated nuclear translocation of the endogenous SHOC2 protein was confirmed in primary skin fibroblasts (Fig. 2e). Treatment with 2-hydroxymyristic acid, an NMT inhibitor, at varying doses reduced or abolished SHOC2S2G’s membrane localization (Supplementary Fig. 2 online), confirming a dependency upon myristoylation. In addition, even in the absence of efficient myristoylation, the mutant did not translocate to the nucleus upon stimulation, indicating possible loss of function. Efficient nuclear translocation was observed for the disease-unrelated SHOC2S2A mutant following EGF stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 3 online), suggesting a specific effect of the disease-causing mutation. To exclude the possibility that SHOC2S2G might play a dominant negative effect by sequestering the wild-type protein to the cell membrane, impairing its EGF-dependent translocation to the nucleus, SHOC2wt and SHOC2S2G heterodimerization was assayed by confocal microscopy and co-immunoprecipitation assays in Cos-1 cells transiently co-transfected with V5- and Myc-tagged proteins (Fig. 3a,b). The experiments demonstrated that these proteins do not heterodimerize, ruling out that possibility. Next, we explored whether SHOC2S2G altered signaling through MAPK. We expressed SHOC2wt or SHOC2S2G in Cos-1, 293T, and Neuro2A cells. While we did not observe significant change in ERK activation in Cos-1 and 293T cells (data not shown), SHOC2S2G expression promoted enhanced EGF-dependent ERK phosphorylation compared to wild type SHOC2, in neuroblastoma Neuro2A cells (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Functional characterization of the disease-causing 4A>G change in SHOC2.

(a) Subcellular localization of co-expressed SHOC2wt (green) and SHOC2S2G (red) documenting that SHOC2S2G does not impair EGF-stimulated SHOC2wt translocation to the nucleus. Imaging of V5-tagged (anti-V5 monoclonal antibody, then Alexa Fluor-594 goat anti-mouse antibody) and Myc-tagged (anti-Myc antibody, then Alex Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit antibody) SHOC2 proteins and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Panels above show Myc-tagged SHOC2wt and V5-tagged SHOC2S2G and below show V5-tagged SHOC2wt and Myc-tagged SHOC2S2G. Cells were imaged basally (left) and following EGF stimulation (right). Bars indicate 20 µm. (b) Lysates of Cos-1 cells co-expressing Myc-tagged SHOC2wt and V5-tagged SHOC2S2G were immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc (above panel) or anti-V5 (below panel) antibody, and immunoprecipitated proteins were visualized by western blotting. These results indicate that SHOC2 proteins do not form heterodimers. (c, d) ERK phosphorylation in V5-tagged SHOC2wt or SHOC2S2G transiently expressed Neuro2A cells basally or following EGF stimulation. Phosphorylation levels are reported as a multiple of basal ERK phosphorylation in cells not transfected with a SHOC2 construct, averaged from four replicates ± s.d. (c). Results for cells expressing the S2G mutant were compared with those overexpressing the wild type protein (below) or untransfected cells (above) at the same time points using two-tailed t-test. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001. Representative blots are also shown (d).

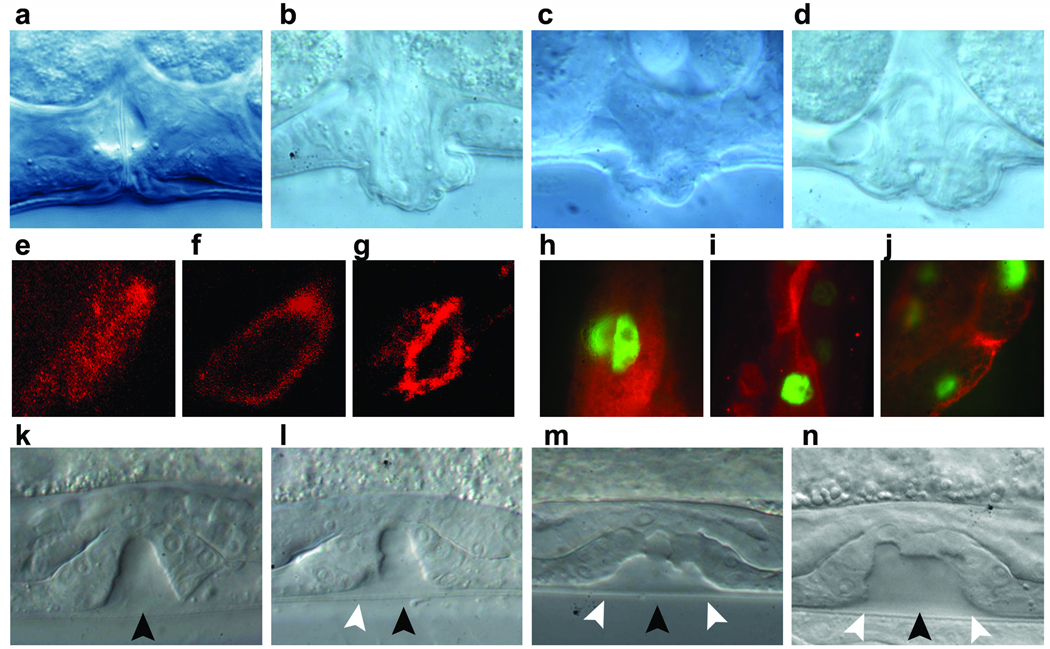

To explore further the functional effects of the SHOC2S2G mutant, we used C. elegans as an experimental model. In C. elegans, reduced SUR-8 function (Sur8rf) causes no phenotype but can suppress the gain-of-function LET-60 (let-60gof)-induced multivulva phenotype (Muv)4. We tested whether expression of SHOC2 proteins could rescue the suppressed Muv phenotype in the sur-8rf;let-60gof genetic background (Supplementary Table 3 online). While SHOC2wt was able to replace SUR-8 functionally, SHOC2S2G failed to do so. Expression of the mutant in let-60gof worms did not suppress the Muv phenotype (Supplementary Table 3 online), excluding dominant negative effects for SHOC2S2G. In a wild-type genetic background, SHOC2S2G expression at embryonic and early larval stages of development caused no visible phenotype. In contrast, at early L3 stage, it caused abnormal vulval development, resulting in protruding vulva (Pvl), decreased egg laying efficiency (Egl) and accumulation of larvae inside the mother with the formation of bag-of-worms adults (Bag phenotype) (Supplementary Table 4 online and Fig. 4b,c). These neomorphic phenotypes were absent in animals expressing SHOC2wt but were also observed when SHOC2wt tagged with an N-myristoylation sequence (myr::SHOC2wt) was expressed (Supplementary Table 4 online and Fig. 4a,d). The SHOC2S2G and myr::SHOC2wt proteins were targeted to the cell membrane in various C. elegans cell types, while SHOC2wt was observed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 4e–j). The defects in vulva formation were not due to increased induction of the vulva cell fate in vulval precursor cells (VPC) as expression of SHOC2S2G did not reduce the penetrance of the vulvaless phenotype of a let-23rf hypomorph mutant (Supplementary Table 5 online), nor increase that of the Muv phenotype of let-60gf animals (Supplementary Table 3 online). At the late L3/early L4 stage, vulva morphogenesis normally begins with the descendants of VPC P6.p detaching from the cuticle and forming a symmetric invagination. Animals in which the expression of SHOC2wt had been induced at early L3 maintained this pattern. In contrast, in larvae expressing SHOC2S2G (17/48) or myr::SHOC2wt (10/22), descendants of VPCs P5.p and/or P7.p also detached from the cuticle, resulting in larger and asymmetric invaginations (Fig. 4k–n). This morphogenesis defect was the earliest detectable neomorphic effect of the SHOC2S2G mutation on vulval development.

Figure 4. Consequences of SHOC2S2G expression in C. elegans vulva development.

(a–d) Nomarski images of vulvas of adult animals. A normal vulva is observed in animals expressing SHOC2wt (a), while in worms expressing SHOC2S2G (b and c) or myr::SHOC2wt (d) a protrusion of the vulva is visible. (e–j) Subcellular localization of V5-tagged SHOC2 proteins in C. elegans cells. In excretory canal cells (e–g) and intestinal cells (h–j), SHOC2wt protein is present throughout the cytoplasm (e and h), while both SHOC2S2G (f and i) and myr::SHOC2wt (g and j) are enriched in or restricted to the plasma membrane. Anti-V5 antibody (red) was used to visualize SHOC2 proteins. In intestinal cells, nuclei express GFP due to pelt-2::GFP plasmid used as a marker for transformation. (k–n) Nomarski images of vulval precursor cells at L3 stage. In animals expressing SHOC2wt only P6.p descendant invaginate (k), while in SHOC2S2G (l and m) and myr::SHOC2wt (n) expressing animals also P5.p (l to n) and P7.p descendants (m and n) detach from the cuticle. Black arrowheads point to P6.p descendant invagination, while white arrowheads point to P5.p and P7.p descendant invagination. Anterior is to the left and dorsal is up in all images.

We discovered that a SHOC2 mutation promoting N-myristoylation of its protein product causes Noonan-like syndrome with loose anagen hair. This acquired fatty acid modification, a unique finding for inherited human disease, results in constitutive membrane targeting, leading to increased MAPK activation in a cell context-specific manner. Cell-specific RAS pathway activation has also been observed with NS-associated SHP-2 mutants.12–14 While not well understood, this phenomenon explains why, despite the ubiquitousness of RAS signaling, development is perturbed in certain tissues in these disorders. It has recent been reported that SHOC2 functions as a regulatory subunit of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1C)6. By binding GTP-MRAS, SHOC2 promotes PP1C translocation to the membrane, allowing PP1C-mediated RAF1 dephosphorylation at residue Ser259, which is required for stable RAF1 translocation to the plasma membrane and catalytic activation. Of note, Ser259 and adjacent residues, which represent a 14-3-3 protein binding site with inhibitory function, are a major hot spot for NS-causing mutations in RAF1 (Ref. 9). According to this model, constitutive membrane translocation of the disease-causing SHOC2S2G is expected to promote prolonged PP1C-mediated RAF1 dephosphorylation at Ser259 and, consequently, sustained RAF1-stimulated MAPK activation, which is consistent with our findings.

In C. elegans, N-myristoylated SHOC2 expression altered morphogenesis during vulval development, a process for which the involvement of Ras signaling is well established. Specification of VPCs, however, was not altered. Rather, perturbation of the morphogenetic movements of the VPC descendant cells was observed. While numerous mutants altering vulval specification and morphogenesis have been identified, far less is known about processes affecting only morphogenesis15,16. It is possible that SHOC2S2G alters Ras signaling in steps downstream of the induction of the vulval fate. Alternatively, SHOC2S2G-induced vulva defects might arise through perturbation of signaling pathways other than Ras-MAPK, such as signaling mediated by the Rho GTPase, Rac, which are critical for vulval morphogenesis17.

A unique feature of the SHOC2 mutation is its association with loose anagen hair. This phenotype occurs in isolation or with NS and has been without molecular cause. Hair shafts from affected individuals show features of the anagen stage of hair follicle development, during which epithelial stem cells proliferate in the hair bulb18. In this condition, however, hair bulbs lack internal and external root sheaths. Our findings suggest perturbation in the proliferation, survival or differentiation of epithelial stem cell-derived cells residing in hair follicles, and implicate SHOC2-mediated signal transduction in this aspect of stem cell biology.

Lastly, we successfully used the human interactome and a network-based statistical method to predict a novel gene for human disease. Our leading candidate, SHOC2, was a relatively obscure gene that caused no phenotype when mutated in worms, evidence of the strength of this approach. For other projects, one can anticipate that successful candidates will not be deemed this favourable, necessitating resequencing of many low-probability candidate genes. Emerging interactome datasets and improved analytic methods are likely to enhance the predictive power of systems biology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the patients and families who participated in the study, the physicians who referred the subjects, Andrew Fire (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA) and James D. McGhee (University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada) for plasmids, and Carlo Ramoni, Serenella Venanzi and Teodoro Squatriti (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) and the Open Laboratory (IGB-CNR, Naples, Italy) for experimental support. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN), funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. We also thank Margherita Cirillo Silengo (Università di Torino, Turin, Italy), Stephanie Spranger (Praxis fuer Humangenetik, Bremen, Germany), Isabel M. Gaspar, (Egas Moniz Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal) and Debora R. Bertola, (HC/FMUSP, Sao Paulo, Brazil) for their contribution in DNA sampling and valuable clinical assistance. This research was funded by grants from Telethon-Italy (GGP07115) and “Convenzione Italia-USA-malattie rare” to M.T., National Institutes of Health (HL71207, HD01294 and HL074728) to B.D.G., SBCNY (P50GM071558) to A.M. and R.I, German Research Foundation (DFG) (ZE 524/4-1) to M.Z., and IRCCS-CSS (Ricerca Corrente 2009) to F.L..

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Resh MD. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farazi TA, Waksman G, Gordon JI. The biology and enzymology of protein N-myristoylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39501–39504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selfors LM, Schutzman JL, Borland CZ, Stern MJ. soc-2 encodes a leucine-rich repeat protein implicated in fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6903–6908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sieburth DS, Sun Q, Han M. SUR-8, a conserved Ras-binding protein with leucine-rich repeats, positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;94:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, Han M, Guan KL. The leucine-rich repeat protein SUR-8 enhances MAP kinase activation and forms a complex with Ras and Raf. Genes Dev. 2000;14:895–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Oses-Prieto J, Burlinqame A, Fried M, McCormick FA. phosphatase holoenzyme comprised of Shoc2/Sur8 and the catalytic subunit of PP1 functions as an M-Ras effector to modulate Raf activity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzanti L, et al. Noonan-like syndrome with loose anagen hair: a new syndrome? Am J Med Genet A. 2003;118A:279–286. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Molecular genetics of NS. In: Zenker M, editor. Monographs in Human Genetics. NS and related disorders: A matter of deregulated RAS signaling. Vol. 17. Basel, Switzerland: Karger Press; 2009. pp. 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger SI, Posner JM, Ma’ayan A. Genes2Networks: connecting lists of gene symbols using mammalian protein interactions databases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutin JA. Myristoylation. Cell Signal. 1997;9:15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tartaglia M, et al. Somatic mutations in PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:148–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araki T, et al. Mouse model of NS reveals cell type- and gene dosage-dependent effects of Ptpn11 mutation. Nat Med. 2004;10:849–857. doi: 10.1038/nm1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh ML, et al. Mutations in PTPN11 implicate the SHP-2 phosphatase in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2004;103:2325–2331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternberg PW. Vulval development. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. Wormbook. WormBook; 2005. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenmann DM, Kim SK. Protruding vulva mutants identify novel loci and Wnt signaling factors that function during Caenorhabditis elegans vulva development. Genetics. 2000;156:1097–1116. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishore RS, Sundaram MV. ced-10 Rac and mig-2 function redundantly and act with unc-73 trio to control the orientation of vulval cell divisions and migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2002;241:339–348. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosti A, et al. Loose anagen hair in a child with Noonan's syndrome. Dermatologica. 1991;182:247–249. doi: 10.1159/000247806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xenarios I, et al. The Database of Interacting Proteins: 2001 update. Nucl Acids Res. 2001;29:239–241. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerrien S, et al. IntAct-open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:D561–D565. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatraryamontri A. MINT: the Molecular INTeraction database. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:D572–D574. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma'ayan A, et al. Formation of regulatory patterns during signal propagation in a Mammalian cellular network. Science. 2005;309:1078–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.1108876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader GD, Betel D, Hogue CWV. BIND: the Biomolecular Interaction Network Database. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:248–250. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beuming T, Skrabanek L, Niv MY, Mukherjee P, Weinstein H. PDZBase: a protein-protein interaction database for PDZ-domains. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:827–828. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numerische Mathematik. 1959;1:269–271. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tartaglia M, et al. Gain-of-function SOS1 mutations cause a distinctive form of NS. Nat Genet. 2007;39:75–79. doi: 10.1038/ng1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allanson JE. Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 1987;24:9–13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.24.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Burgt I, et al. Clinical and molecular studies in a large Dutch family with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53:187–191. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320530213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voron DA, Hatfield HH, Kalkhoff RK. Multiple lentigines syndrome. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1976;60:447–456. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarkozy A . LEOPARD syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. In: Zenker M, editor. Monographs in Human Genetics. NS and related disorders: A matter of deregulated RAS signaling. Vol. 17. Basel, Switzerland: Karger Press; 2009. pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts A, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833–842. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utsumi T, et al. Amino acid residue penultimate to the amino-terminal Gly residue strongly affects two cotranslational protein modifications, N-myristoylation and N-acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10505–10513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vachon L, Costa T, Hertz A. GTPase and adenylate cyclase desensitize at different rates in NG108-15 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;31:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sulston JE, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, the Community of C. elegans Researchers, editor. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans after microinjection of DNA into germline cytoplasm: extrachromosomal maintenance and intergration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duerr JS. Immunohistochemistry. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. WormBook; 2006. http://www.wormbook.org. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.