Abstract

Two new cyclodepsipeptides designated bacillistatins 1 (1) and 2 (2) have been isolated from cultures of a sample of Bacillus silvestris that was obtained from a Pacific Ocean (southern Chile) crab. Each 12-unit cyclodepsipeptide strongly inhibited growth of a human cancer cell line panel, with GI50s of 10−4–10−5 μg/mL, and each compound was active against antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. The structures were elucidated by a combination of X-ray diffraction and mass and 2D NMR spectroscopic analyses, together with chemical degradation.

Marine microorganisms are rapidly becoming a very useful source of new cancer cell growth inhibitory substances that have unique structures. Illustrative are recent examples of antineoplastic substances from marine bacteria,1a–h fungi,2a–h cyanobacteria,3a–e and dinoflagellates.4a–d As part of our extended evaluation of terrestrial and marine microorganisms as sources of new anticancer drug candidates, we collected a marine crab on Chiloé Island, Chile, in 1998. A Bacillus species, subsequently identified as B. silvestris, was isolated from the crab, and extraction of the scaled up bacterial broth has led to the identification of two new cyclodepsipeptides with antibacterial and human cancer cell line inhibitory activity. Bioactive cyclodepsipeptides have been isolated previously from other Bacillus species, including B. cereus,5a, d B. polymyxa,5c and B. natto.5b Members of the genus Bacillus are common in both terrestrial and marine sediments. Bacillus silvestris was first described in 1999, when it was isolated from a sample of forest soil in Germany,6a and more recently it was identified in water samples taken from the southern Baltic Sea, a brackish environment.6b

Results and Discussion

The Bacillus silvestris culture was scaled up and extracted as described in the Experimental Section to give a dark-brown gum (3.14 g; P388 lymphocytic leukemia: ED50 0.0066 μg/mL), which was shown by HPLC analysis to comprise a mixture with at least six closely spaced peaks. Subsequent high-resolution LC-MS showed the mixture to be more complex than was apparent from the HPLC analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

LC/MS Data for B. sylvestris Extract and Valinomycin (3)

| peak (min) | compound | [M + H]+ (m/z) | molecular formula | error (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32.30 | 1125.663 | C55H92N6O18 | 7.4 | |

| 32.92 | 1125.662 | C55H92N6O18 | 6.5 | |

| 32.92 | 1139.679 | C56H94N6O18 | 7.6 | |

| 33.65 | 1139.668 | C56H94N6O18 | −2 | |

| 33.65 | 1153.686 | C57H96N6O18 | 0 | |

| 34.37 | 1139.660 | C56H94N6O18 | −9.1 | |

| 34.37 | 1153.690 | C57H96N6O18 | 3.5 | |

| 35.21 | 2 | 1153.699 | C57H96N6O18 | 11 |

| 36.11 | 1 | 1153.697 | C57H96N6O18 | 9.6 |

| reference | 3 | 1111.640 | C54H90N6O18 |

Attempts at separation by way of gel permeation and partition chromatography using Sephadex LH-20 and silica gel Lobar C8 columns were unsuccessful. Separation using an Ito multi-layer coil countercurrent separator was undertaken, with 9:1 CH3OH–H2O as the stationary phase and hexane–CH2Cl2 as the mobile phase. While this did not provide resolution of the active components, it allowed removal of the more polar impurities and yielded an active 0.88-g fraction suitable for small-scale preparative HPLC, which led to the isolation of two crystalline components that significantly inhibited cancer cell growth, designated bacillistatins 1 (1, 34.0 mg) and 2 (2, 20.1 mg). Table 1 shows that 1 and 2 have molecular weights a little higher than that of the antibiotic valinomycin (3).

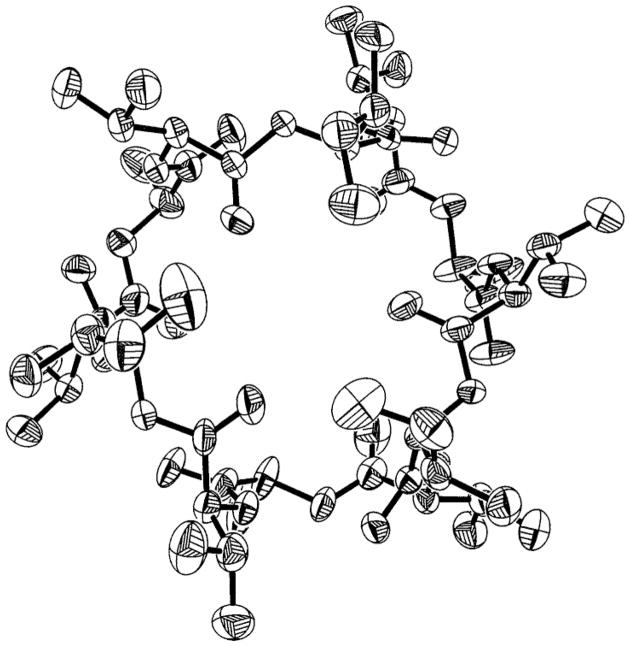

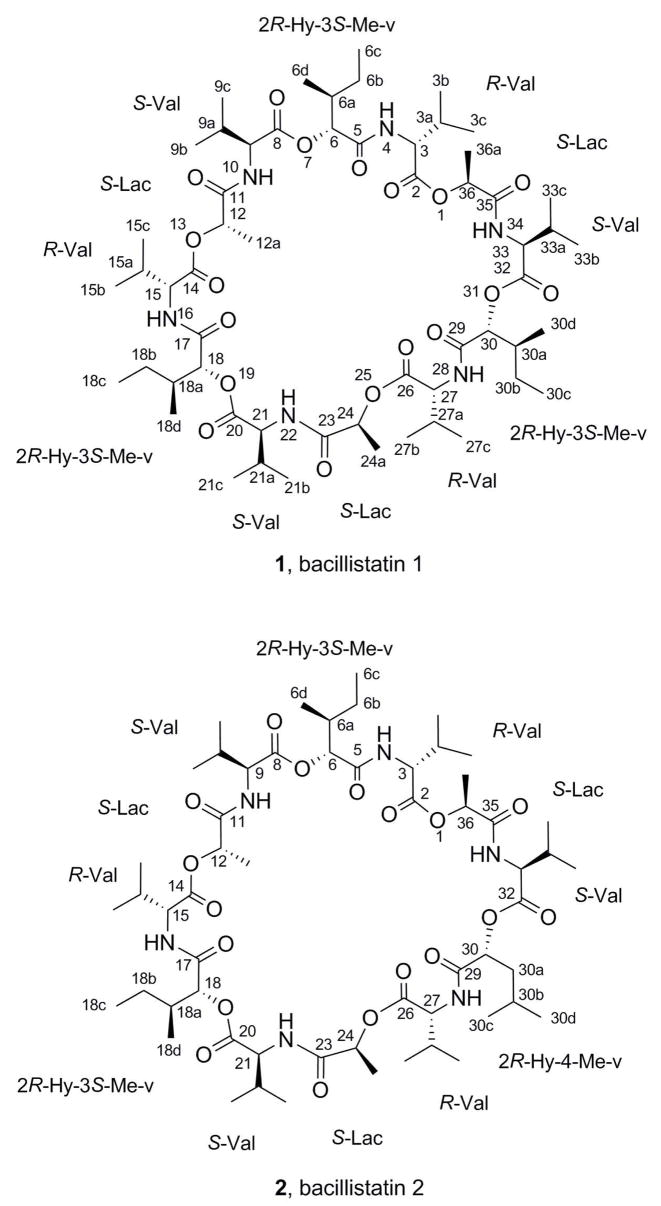

By X-ray crystallographic analysis of 1 (Figure 1), its structure was shown to be a 36-membered cyclodepsipeptide that incorporates R-valine (R-Val), S-lactic acid, (S-Lac), S-valine (S-Val), and 2R-hydroxy-3S-methyl-valeric acid (2R-Hy-3S-Me-v) and that closely resembles 3, which consists of three repeating sequences of R-Val, S-Lac, S-Val, and 2R-hydroxyisovaleric acid. However, initial attempts at X-ray crystal structure analysis of 2 did not give unequivocal results, and a chemical degradation of each compound was carried out in order to elucidate the structures.

Figure 1.

X-ray structure (excluding hydrogens) of bacillistatin 1 (1), depicted as 50% probability thermal ellipsoids.

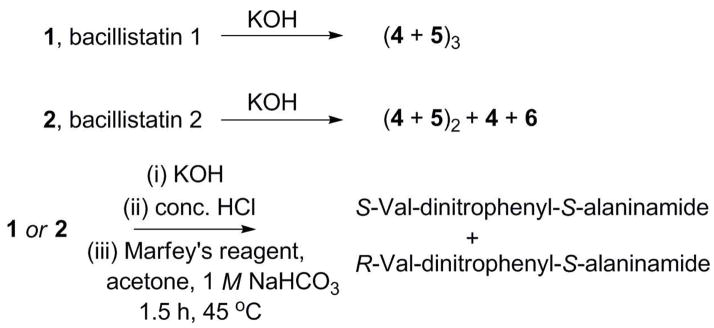

As outlined in Scheme 1, 1 and 2 were subjected to base hydrolyses,5a and the products were analyzed by HPLC-MS (Table 2). Hydrolysis of 1 gave a product that has the same molecular weight and HPLC retention time as the S-Lac–S-Val (4) released by hydrolysis of 3, along with a later peak that has the correct molecular weight for the 2R-hydroxy-3S-methyl-valeric acid–R-valine condensation product 5. Thus, the components of the repeating units in 1 were identified and found to be consistent with the X-ray crystal structure.

Scheme 1.

Chemical Degradation of 1 and 2

Table 2.

LC-MS Identification of Products of Hydrolyses of 1 and 2a

| substrate | peak | [M + H]+ (m/z) | molecular formula | product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 190.1172 | C8H16NO4 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 232.1499 | C11H22NO4 | 5 |

| 2 | 1 | 190.1163 | C8H16NO4 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 232.1499 | C11H22NO4 | 6 |

| 2 | 3 | 232.1502 | C11H22NO4 | 5 |

HPLC conditions: Zorbax SB C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm); 10% to 40% acetonitrile in 0.1% aq. TFA at 1.0 mL/min for 30 min.

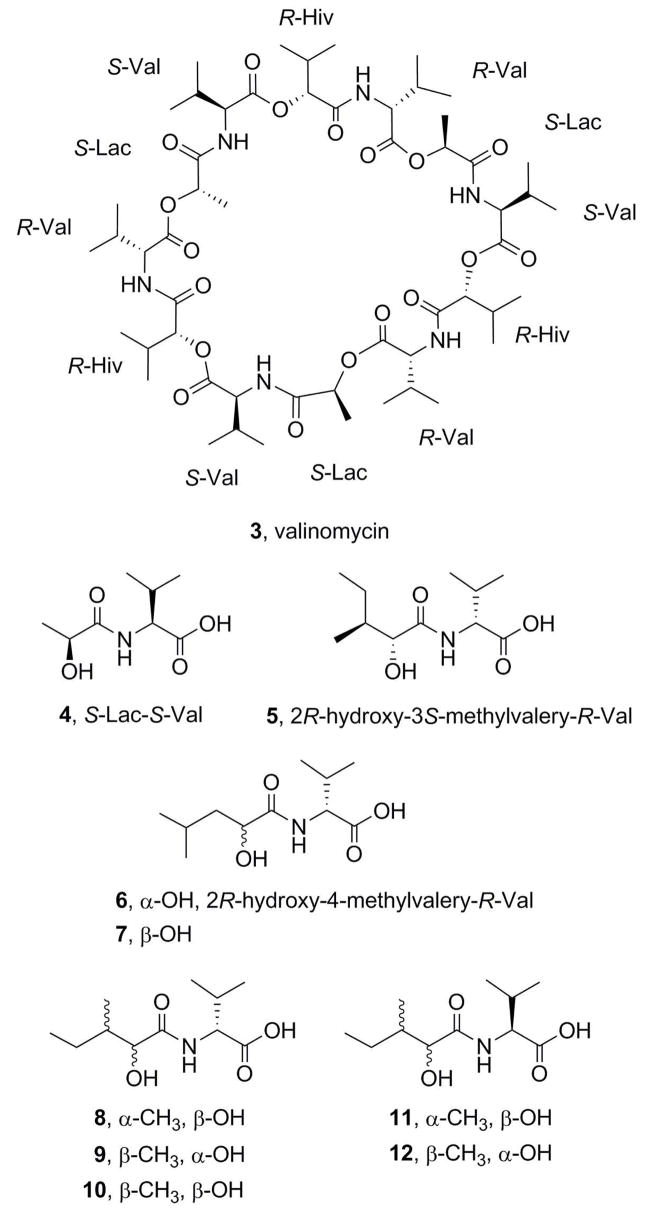

Hydrolysis of 2 gave the same two products and HPLC peaks as were observed after hydrolysis of 1, and in addition there was a third peak that has the same molecular weight as 5 but a slightly shorter retention time (Table 3). The ratio of the peaks corresponding to these isomers was approximately 1:2, suggesting that one of the three units in 2 was somewhat different. When the base hydrolyses of 1 and 2 were followed by acid hydrolyses and derivatization with Marfey’s reagent (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-alanine amide; FDAA), only the S-Val and R-Val derivatives were identified by HPLC (Scheme 1; Table 4). Therefore, the difference between the two bacillistatins was shown to lie in the hydroxy acid moiety. Comparison of the high-field 13C NMR spectra of 1 and 2 also supported this location for the difference between these closely related cyclodepsipeptides (Table 5), suggesting the replacement of one of the 3S-methyl-valeric acid moieties in 1 by a 4-methyl-valeric acid (4-Me-v) in 2. The signal at d 26.15 in the 13C NMR spectrum of 1 was assigned to the 6b-, 18b-, and 30b-methylenes of the 3S-methyl-valeric acid, whereas the signal at d 40.79 in the spectrum of 2 was assigned to the 30a-methylene of the 4-methyl-valeric acid; these signals corresponded closely with calculated values, and APT experiments confirmed the assignments. In general, the symmetry of 1 resulted in a simplified 13C NMR spectrum with perfect overlap of the signals, whereas 2 gave rise to a complex spectrum with discrete signals for each carbon atom.

Table 3.

HPLC Comparison of Bacillistatin Hydrolyses Productsa

| substrate | hydrolysis product or reference | retention time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| reference | 5 | 22.02 |

| reference | 6 | 21.34 |

| 2 (peak 2)b | 6 | 21.38 |

| 2 (peak 3)b | 5 | 22.05 |

| 1 (peak 2)b | 5 | 22.05 |

HPLC conditions: Zorbax SB C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm); 10% to 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% aq. TFA at 1.5 mL/min for 30 min; ELSD detection.

See Table 2.

Table 4.

Retention Time of the DNPA-Amino Acidsa following Marfey’s Derivatization of the Products of Hydrolyses of 1, 2 and 3b

| substrate | DNPA-S-Val (min) | DNPA-R-Val (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16.775 | 19.600 |

| 2 | 16.815 | 19.666 |

| 3 | 16.835 | 19.638 |

2,4-Dinitrophenyl-5S-alaninamide amino acid.

HPLC conditions: Zorbax SB C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm); gradient of 10% to 40% acetonitrile in 0.1% aq. TFA at 1.0 mL/min for 30 min.

Table 5.

13C NMR Spectroscopic Assignments for Bacillistatins 1 (1) and 2 (2) a

| 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| position | δc, mult. | Position | δc, mult. |

| 6c, 18c, 30c | 11.74, CH3 | 6c, 18c | 11.77, CH3 |

| 6d, 18d, 30d | 14.23, CH3 | 6d, 18d | 14.27, CH3 |

| 12a, 24a, 36a | 17.06, CH3 | 12a, 24a | 16.92, 17.12, CH3 |

| 3b, 15b, 27bb | 18.99, CH3 | 36a | 17.27, CH3 |

| 3c, 15c, 27cb | 19.22, CH3 | 3b, 3c, 9b, 9c, 15b, 15c, 21b, 21c, 27b, 27c, 33b, 33c | 18.97, 19.17, 19.21, 19.27, 19.39, 19.46, 19.58, 19.81, 19.86, CH3 |

| 9b, 21b, 33bc | 19.46, CH3 | 30c | 21.49, CH3 |

| 9c, 21c, 33cc | 19.64, CH3 | 30d | 23.19, CH3 |

| 6b, 18b, 30bd | 26.15, CH2 | 30b | 24.51, CH |

| 6b, 18bd | 26.20, 26.33, CH2 | ||

| 9a, 21a, 33a | 28.36, CH | 9a, 21a | 28.30, 28.36, CH |

| 3a, 15a, 27a | 28.47, CH | 3a, 15a | 28.41, 28.43, CH |

| 27a | 28.46, CH | ||

| 33a | 28.70, CH | ||

| 6a, 18a, 30a | 36.84, CH | 6a, 18a | 36.77, 36.88, CH |

| 30ad | 40.79, CH2 | ||

| 27 | 58.51, CH | ||

| 3, 15, 27 | 58.77, CH | 3, 15, CH | 59.10, 59.16 |

| 33 | 60.85 | ||

| 9, 21, 33 | 60.32, CH | 9, 21 | 60.95, CH |

| 36 | 70.18, CH | ||

| 12, 24, 36 | 70.35, CH | 12, 24 | 70.54, 70.62, CH |

| 30 | 73.39, CH | ||

| 6, 18, 30 | 77.32, CH | 6, 18 | 76.60, CH |

| 8, 20, 32 | 169.98, CO | 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35 | 169.89, 170.21, 170.28, 170.88, 170.94, 171.51, 171.70, 171.87, 172.17, 172.27, 172.30, 172.61, CO |

| 2, 14, 26 | 170.21, CO | ||

| 11, 23, 35 | 171.64, CO | ||

| 5, 17, 29 | 172.41, CO | ||

Recorded in CD3OD

Assignments may be reversed.

Assignments may be reversed.

Assigned via APT.

To confirm the identity of the hydroxy acid–valine moiety in 2, a synthetic sample of 2R-hydroxy-4-methyl-valeryl-R-Val (6) was prepared and found to have the same HPLC retention time as the minor product from base hydrolysis of 2 (Table 3). Compound 5 was also prepared as a reference, and Tables 6 and 7 give the 1H and 13C NMR data for 5 and 6 and the intermediate benzyl esters. As in macrocycle 2, the methylene groups at C-6 (in 5) and at C-5 (in 6), as well as the neighboring methyl groups, gave rise to diagnostic peaks in the 13C NMR spectrum. The other isomers (7–12) were prepared in parallel experiments and eliminated as possibilities by HPLC analysis. Bacillistatin 2 (2) was therefore determined to comprise two units of S-Lac–S-Val–2R-hydroxy-3S-methyl-valeryl–R-Val and a third unit in which a 4-methyl-valeric acid replaces the 3S-methyl-valeric acid. Structure 2 has now been synthesized, as reported in the accompanying paper,7 and its identity with the natural product confirmed.

Table 6.

1H NMR Spectroscopic Assignments for Carboxylic Acids 5 and 6 and the Corresponding Benzyl Esters (recorded in CDCl3)

| position | 5 δH, mult. | 6 δH, mult. | 5, benzyl ester δH, mult. | 6, benzyl ester δH, mult. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2b, 2c, 5a, 7 | 0.820–0.998 | 0.824–0.971 | ||

| 2b, 2c, 6a, 7 | 0.916–0.976 | 0.853–0.963 | ||

| 6-Ha | 1.260–1.392, m | 1.262–1.381, m | ||

| 6-Hb | 1.434–1.562, m | 1.416–1.533, m | ||

| 5-Ha, 5-Hb | 1.489–1.617, m | 1.487–1.679, m | ||

| 6 | 1.765–1.948, m | 1.795–1.908, m | ||

| 5 | 1.815–1.920, m | 1.860–1.980, m | ||

| 2a | 2.160–2.300, m | 2.165–2.330, m | 2.170–2.278, m | 2.119–2.265, m |

| OH | 3.311 | 2.992 | 3.443 | |

| 4 | 4.043–4.062, m | 4.181–4.223, m | 4.157, s | 4.155–4.186, m |

| 2 | 4.372–4.399, m | 4.421–4.448, m | 4.598–4.644, m | 4.569–4.615, m |

| 8 | 5.109–5.228, m | 5.098–5.223, m | ||

| NH/OH | 4.91 | 7.395, 7.424 | 7.072–7.102 | 7.098, 7.127 |

| phenyl | 7.351 | 7.345 |

Table 7.

13C NMR Spectroscopic Assignments for Carboxylic Acids 5 and 6

| position | 5a δc, mult. | 6b δc, mult. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 173.42, CO | 173.47, CO |

| 2 | 56.37, CH | 56.83, CH |

| 2a | 30.32, CH | 30.99, CH |

| 2b | 19.12, CH3 | 19.65, CH3 |

| 2c | 17.71, CH3 | 18.28, CH3 |

| 3 | 173.10, CO | 174.99, CO |

| 4 | 72.96, CH | 70.21, CH |

| 5 | 37.69, CH | 44.27, CH2 |

| 5a | 13.24, CH3 | |

| 6 | 25.77, CH2 | 24.56, CH |

| 6a | 24.09, CH3 | |

| 7 | 11.83, CH3 | 22.11, CH3 |

Recorded in CDCl3.

Recorded in DMSO.

In broth microdilution susceptibility assays,8 1 and 2 were active against Streptococcus pneumoniae and S. pyogenes (Table 8). Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) for S. pneumoniae were equal to, or a twofold dilution higher than, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), indicating that 1 and 2 are bactericidal for S. pneumoniae. When broth microdilution assays with S. pneumoniae and S. pyogenes were performed in the presence of 25% heat-inactivated human serum, MICs were > 64 μg/mL.

Table 8.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBC) of Bacillistatins 1 (1) and 2 (2)a

| MIC (μg/mL)/MBC (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|

| clinical isolate or (reference strain) | 1 | 2 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) | 2/4 | ½ |

| penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae | 1/2 | 1/1 |

| multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae (ATCC 700673) | <0.5/1 | <0.5/<0.5 |

| S. pyogenes | 2/ND | 8/>64 |

| S. pyogenes | 4/>32 | 2/>16 |

Against Cryptococcus neoformans (ATCC 90112), Candida albicans (ATCC 90028), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), Micrococcus luteus (Presque Isle 456), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Enterobacter cloacae (ATCC 13047), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (ATCC 13637), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (ATCC 49226) there was no inhibition at 64 μg/mL.

Bacillistatins 1 and 2 were more inhibitory than 3 against a human cancer cell-line panel (Table 9) and because of their outstanding activity are being further evaluated, as are methods for biosynthesis and organic synthesis7 that will allow structural modification. The remaining components of the original extract are also being further investigated.

Table 9.

Inhibition of the Murine P388 Lymphocytic Leukemia (ED50 μg/mL) and Human Cancer Cell Lines (GI50 μg/mL) by Bacillistatins 1 (1) and 2 (2), with Valinomycin (3) as Referencea

| cell lineb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | P388 | BXPC-3 | MCF-7 | SF-268 | NCI-H460 | KM20L2 | DU145 |

| 1 | 0.023 | 0.00095 | 0.00061 | 0.00045 | 0.00230 | 0.00087 | 0.00150 |

| 2 | 0.013 | 0.00034 | 0.00031 | 0.00180 | 0.00045 | 0.00026 | 0.00086 |

| 3 | 0.120 | 0.0019 | 0.0010 | 0.0027 | 0.0025 | 0.0008 | 0.0035 |

DMSO was used as vehicle in the testing.

Cancer cell lines in order: murine lymphocytic leukemia (P388); pancreas (BXPC-3); breast (MCF-7); CNS (SF-268); lung (NCI-H460); colon (KM20L2); prostate (DU-145).

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Solvents used for the chromatographic procedure were redistilled. Sephadex LH-20 employed for gel permeation and partition chromatography was obtained from Pharmacia Fine Chemicals AB, Uppsala, Sweden. The silica gel GHLF Uniplates for thin-layer chromatography were supplied by Analtech, Inc., Newark, DE. The TLC results were viewed under UV light and developed with ceric sulfate–sulfuric acid (heating for 3 min). Reversed-phase HPLC experiments were performed on Luna C8 (250 × 10 mm, 5 μm), Zorbax C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), and Discovery C8 (250 × 4.6 or 10 mm, 5 μm) columns attached to Gilson HPLC, Agilent HP1100, or Walters Delta-600 equipment, monitored with UV and ELSD detectors. Low-pressure silica chromatography was carried out on Lobar (B) columns (E. Merck) in 2-propanol–hexane (1:39) and monitored with an ISCO zinc-lamp 214-nm detector. The optical rotation data were determined with a Perkin-Elmer 241 polarimeter. UV spectra were from a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 3β UV/vis spectrophotometer equipped with a Hewlett-Packard Laser Jet 2000 plotter. IR spectra were recorded on an Avatar 360 FT-IR instrument with a single-reflection HATR sample accessory. The NMR experiments were conducted with a Varian Unity INOVA-500 spectrometer operating at 500 MHz and 125 MHz for 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy, respectively, with use of Shigemi sample tubes and tetramethylsilane as reference. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on JEOL LCmate or GCmate instruments with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) as the reference standard. X-ray structure analyses were performed on a Bruker AXS Smart 6000 diffractometer.

Specimen Collection and Fermentation

A marine crab collected in 1998 near the port town of Quellon on Chiloé Island was rinsed in sterile water, ground with a sterile mortar and pestle, and plated on solid media containing autoclaved local seawater. Pure cultures were shipped to our laboratory for screening. A bacterial isolate from the crab with significant human cancer cell line activity was identified by 16S rRNA sequencing (Acculab, Newark, DE) as Bacillus silvestris (% difference = 0.09; confidence level to species). Bacillus silvestris was scaled up to 378 L at 125 rpm for six days at room temperature in an aqueous medium containing dextrose (0.5 g/L), yeast extract (1.25 g/L), peptone (2.5 g/L), and instant ocean (26.5 g/L).

Extraction and Solvent Partition of Bacillus silvestris

The bacterial broth was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the extract was concentrated to a dark oil that was redissolved in CH3OH–H2O (3:2). The aqueous solution was successively extracted with hexane and CH2Cl2, and solvent was removed from both extracts and from the remaining aqueous solution. The CH2Cl2-soluble (4.65 g; P388: ED50 0.01 μg/mL) and the CH3OH–H2O-soluble (0.8 g; P388: ED50 0.24 μg/mL) extracts were retained. The hexane-soluble extract (44.2 g; P388: ED50 0.02 μg/mL) was partitioned between hexane and acetonitrile to give a hexane-soluble yellow oil (26.8 g; P388: ED50 0.08 μg/mL) and an acetonitrile-soluble viscous gum (15.9 g; P388: ED50 0.03 μg/mL). An 11-g aliquot of the acetonitrile-soluble extract was dissolved in 9:1 CH3OH–H2O, and this solution was extracted (5 ×) with 9:1 hexane–CH2Cl2. The CH3OH–H2O solution was then concentrated to a dark-brown gum (3.14 g; P388: ED50 0.007 μg/mL).

Isolation of Bacillistatins 1 and 2

The cancer cell growth inhibitory CH3OH–H2O fraction (3.14 g), obtained as described above, was shown by HPLC [Zorbax SB C8 column (150 × 4.6 mm); 19:1 acetonitrile–0.05 M acetic acid, 40 °C, 2 mL/min] to contain at least six closely spaced and late-eluting compounds. Fractionation on an Ito multi-layer coil countercurrent separator was undertaken, with 9:1 CH3OH–H2O as the stationary phase and hexane–CH2Cl2 as the mobile phase, which allowed removal of the polar impurities (1.56 g). From the remaining 0.88-g bioactive mixture, 25-mg aliquots were fractionated by semi-preparative HPLC on a Hewlett-Packard HP-1100 LC with a Luna C8 column (Phenomenex; 250 × 10 mm) in 9:1 CH3OH–0.05 M acetic acid (isocratic; 3.5 mL/min). The column effluent was monitored at 235 nm, and about 10% of the flow was diverted by a splitter valve (Upchurch P-451) to an ELSD detector (Sedex-55), because the sample did not absorb strongly except at lower wavelengths. Cyclodepsipeptides 1 (34.0 mg) and 2 (20.1 mg) were obtained by pooling and concentrating the fractions that showed peaks at retention times of 52.40 and 44.97 min, respectively, from several runs.

Bacillistatin 1 (1)

Colorless prisms from CH3OH–H2O; 1H NMR (DMSO) δ 0.80–0.95 (54 H, m, 18 × CH3), 1.14–1.26 (9 H, m, CH3-12a, -24a, -36a), 1.26–1.37 (6 H, m, CH2-6b, -18b, -30b), 1.90–1.96 (3 H, m, CH-6a, -18a, -30a), 2.12–2.22 (6 H, m, CH-3a, -9a, -15a, -21a, -27a, -33a), 4.24 (3 H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, CH-9, -21, -33), 4.50 (3 H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH-3, -15, -27), 4.94 (3 H, d, J = 3.2 Hz, CH-6, -18, -30), 5.04 (3 H, q, J = 6.4 Hz, CH-12, -24, -36), 7.86 (3 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH-4, -16, -28), 8.43 (3 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH-10, -22, -34); 13C NMR data, see Table 5; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 1153.6881 [M+H]+ (calcd for C57H97N6O18, 1153.68594).

X-ray Crystal Structure Determination (1)

A plate-shaped crystal (~ 0.32 × 0.29 × 0.11 mm), grown from a CH3OH–H2O solution, was mounted on the tip of a glass fiber. Cell parameter measurements were taken and data collected at 153±1 K with a Bruker SMART 6000 diffractometer system using Cu K radiation. A sphere of reciprocal shape was covered by use of the Multirun technique.9 Thus, six frames of data were collected with 0.396° steps in and a seventh set with 0.396° steps in ϕ so that 98.5% coverage of all unique reflections to a resolution of 0.822 Å was accomplished.

Crystal Data

C57H96N6O18, FW = 1153.40, rhombohedral, R3, a = b = c = 26.6254(4) Å, ά = β = γ = 118.0470(10) °, V = 6775.05(18) Å3, Z = 4, ρc = 1.131 mg/m3, μ(Cu Kά) = 0.690 mm−1, λ= 1.54178 Å.

A total of 48 578 reflections was collected, of which 14 573 reflections were independent reflections (R(int) = 0.0661). Subsequent statistical analysis of the data set with the XPREP10 program indicated the rather uncommon spacegroup R3. Final cell constants were determined from the set of the 8732 observed (>2σ(I)) reflections. An absorption correction was also applied to the data with the Bruker program SADABS.11 The structure solution and refinement was readily accomplished with the direct-methods program SHELTXL12,13 using 8732 (>2σ(I)) observed reflections. All non-hydrogen atom coordinates were located in a routine run using default values for that program. The remaining H atom coordinates were calculated at optimum positions with that program, and all non-hydrogen atoms were then refined anisotropically in a full-matrix least-squares refinement procedure. The H atoms were included, their Uiso thermal parameters fixed at either 1.2 or 1.5 (depending on the atom type) of the value of the Uiso of the atom to which they were attached, and forced to ride that atom. The final residual R1 value for the model shown in Figure 2 was 0.0959 for observed data and 0.1233 for all data. The goodness-of-fit on F2 was 0.959. The corresponding Sheldrick R values were wR2 of 0.2292 and 0.2472, respectively. The final model for 1 is shown in Figure 1 and is composed of three repeating peptide units, each of which contains the following sequence: R-Val, S-Lac, S-Val, and 2R-hydroxy-3S-methyl-valeric acid. The asymmetric unit cell of 1 was found to contain one complete 36-membered macrocyclic depsipeptide ring and an additional momomeric unit consisting of R-Val–S-Lac–S-Val–2R-Hy-3S-Me-v, which is one-third of another molecule in an adjoining asymmetric cell unit. As a consequence, the unit cell contains four bacillistatin 1 molecules. A final difference Fourier map showed some residual electron density, the largest difference peak and hole being 1.147 and − 0.496 e/Å3, respectively. However, all residual peaks were attributed to local disorder of the non-hydrogen atoms already assigned. Final bond distances and angles were all within expected and acceptable limits. The Flack absolute structure parameter χ for the model shown in Figure 1 was 0.2(3), indicating that the absolute configuration depicted is the correct stereoisomer of 1.

Bacillistatin 2 (2)

Colorless prisms from CH3OH–H2O; 1H NMR (DMSO) δ 0.79–0.97 (54 H, m, 18 × CH3), 1.14–1.26 (9 H, m, CH3-12a, -24a, -36a), 1.26–1.36 (4 H, m, CH2-6b, -18b), 1.46–1.58 (1 H, m, Ha-30a), 1.58–1.75 (1 H, m, Hb-30a), 1.88–2.00 (3 H, m, CH-6a, -18a, -30a), 2.12–2.24 (6 H, m, CH-3a, -9a, -15a, -21a, -27a, -33a), 4.18–4.30 (3 H, m, CH-9, -21, -33), 4.38–4.45 (2 H, m, CH-3, -15), 4.45–4.54 (1 H, m, CH-27), 4.93 (3 H, m, CH-6, -18, -30), 5.04 (3 H, m, CH-12, -24, -36), 7.90 (2 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH-4, -16), 7.96 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH-28), 8.38 (3 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH-10, -22, -34); 13C NMR data, see Table 5; HRMS (APCI+) m/z 1153.6885 [M+H]+ (calcd for C57H97N6O18, 1153.68594).

Base Hydrolysis of Bacillistatin 1 (1) 5a

To a solution of 1 (100 μg) in CH3OH (100 μL) in a cone-bottomed vial was added an aqueous solution of KOH (1.2 N; 100 μL), and the mixture was heated at 50 °C for 1.5 h before being cooled and neutralized with aqueous HCl (6 N; 20 μL). The resulting mixture was dried under nitrogen, with final drying under high vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in water (100 μL). Only valine (R or S) was detected when a 2-μL aliquot of the aqueous solution was analyzed for amino acid content. The remainder of the product solution was investigated by LC-MS: a HPLC peak for one of the products had the same retention time as that of 4, which was generated by hydrolysis of 3, and a later peak had the correct molecular weight for a 2-hydroxy-3-methyl-valeryl-valine isomer with a configuration shown by the X-ray analysis above to be 2R-hydroxy-3S-methyl-valeryl-R-valine (5).

Base Hydrolysis of Bacillistatin 2 (2)

The same procedure was followed as described above for 1. Amino acid analysis of an aqueous solution of the product detected valine, and HPLC analysis showed the same two peaks (corresponding to 4 and 5) as were generated by hydrolysis of 1. A third peak was also observed, with the same molecular formula as 5 but with a slightly longer retention time and in about half the concentration of 5.

Determination of the Valine Configuration in 1 and 2 5a

The preceding base hydrolyses were repeated with 1.2 N KOH on 100-μg samples of 1, 2 and 3. The products were next treated with 6 N HCl (100 μL) in 1-mL cone-bottomed vials with Teflon-lined screw caps, and the mixtures were heated overnight at 110 °C. The vials were then cooled and the liquid contents transferred by syringe to similar vials prior to being dried in a vacuum oven. The crude hydrolysates were redissolved in water before being treated with a solution of 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-alanine amide (FDAA, Marfey’s reagent; 1% in acetone; 50 μL), followed by NaHCO3 (1 M; 10 μL). The tubes containing the resultant mixtures were placed in a block heater for 1.5 h at 45 °C, and the mixtures were then cooled, neutralized with 2 N HCl (5 μL), and diluted with CH3OH (500 μL) for HPLC. The derivatives were separated by chromatography on a Zorbax SB C18 column in a gradient of 20–50% acetonitrile in aqueous TFA (0.1%) at 1.0 mL/min for 30 min. The column was monitored at 340 nm and by ELSD. Reference standards of DNPA-amino acids were also prepared from R-valine and S-valine. This procedure established the presence of both R-Val and S-Val in each cyclodepsipeptide (Table 4).

Illustrative Procedure for Synthesis of Chiral Isomers 5–12: Preparation of 6. 2R-Hydroxy-4-methyl-valeric acid 14

To a solution of D-leucine (0.5 g) in aqueous perchloric acid (0.5 N; 200 mL) that was cooled to < 5 °C and stirred vigorously was added a solution of sodium nitrite (7 g) in ice-cold water (50 mL). Stirring was continued for 30 min with warming to room temperature, and the mixture was then heated to reflux under a current of nitrogen until evolution of N2O4 had ceased. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, saturated with sodium chloride, and extracted once with ethyl acetate (50 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, and removal of solvent yielded a pale yellow oil with suspended colorless solids. The residue was taken up in a small volume of CH2Cl2 and the solids were collected; the filtrate was dried under nitrogen, with final drying in a vacuum oven, to give 2R-hydroxy-4-methyl-valeric acid as a clear oil (0.371 g).

R-Val Benzyl Ester

To a suspension of R-Val-OBz p-toluenesulfonate (0.76 g) in H2O (5 mL) was added saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (340 mg in 5 mL). The mixture was vigorously sonicated until the suspension had become a gelatinous semisolid, and it was then extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 5 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over MgSO4, and removal of solvent yielded R-Val-OBz as a clear oil that crystallized on standing (0.41 g).

2R-Hydroxy-4-methyl-valeryl-R-valine (6)

To R-Val-OBz (0.41 g) was added a solution of 2R-hydroxy-4-methyl-valeric acid (0.37 g) in CH2Cl2 (10 mL), followed by a solution of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCI; 0.41 g) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4.5 h and then retained at 5 °C for 48 h. The precipitated dicyclohexylurea was collected, and the filtrate was washed successively with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, 2 N HCl, and H2O. The organic phase was dried over MgSO4 and the solvent was removed (with final drying in a vacuum oven) to yield a pale yellow gum (0.76 g), which was fractionated by chromatography on a prepacked silica column (Ace Glass, Inc.) in hexane–2-propanol (39:1) at 6 mL/min to give several products, including 2R-hydroxy-4-methylvaleryl-R-valine benzyl ester: HRMS (APCI+) m/z 322.1989 [M+H]+ (calcd for C18H28NO4, 322.2018). Removal of the benzyl group was carried out as follows: to a solution of the benzyl ester (70 mg) in a mixture of ethanol–H2O–acetic acid (5 mL; 7:2:1) was added 10% palladium-on-charcoal (25 mg). The mixture was stirred under hydrogen for 3 h, and the solvent was filtered. Removal of solvent from the filtrate yielded 6 as a colorless oil (46.9 mg): HRMS (APCI+) m/z 232.1533 [M+H]+ (calcd for C11H22NO4, 232.1549). For 1H and 13C NMR data, see Tables 6 and 7.

Human Cancer and Murine Lymphocytic Leukemia Cell Line Procedures

The inhibition of human cancer cell growth was determined with the National Cancer Institute’s standard sulforhodamine B assay as earlier described.15 In summary, cells in a 5% fetal bovine serum/RPMI-1640 medium solution were inoculated in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. Serial dilutions of the compounds were then added. After 48 h, the plates were fixed with trichloroacetic acid, stained with sulforhodamine B, and read with an automated microplate reader. A growth inhibition of 50% (GI50 or the drug concentration causing a 50% reduction in the net protein increase) was calculated from optical density data with Immunosoft software.

Mouse lymphocytic leukemia P388 cells16 were incubated for 24 h in a 10% horse serum/Fisher medium solution followed by a 48-h incubation with serial dilutions of the compounds. Cell growth inhibition (ED50) was calculated with a Z1 Beckman/Coulter particle counter.

Acknowledgments

The very important financial support was provided by Outstanding Investigator Grant CA44344-10-12, grant R01 CA90441-01-05, grant 2R56 CA090441-06A1, and grant 5R01 CA090441-07 from the Division of Cancer Treatment, Diagnosis and Centers, National Cancer Institute, DHHS; the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation; Dr. Alec D. Keith; the Arizona Disease Control Research Commission; the Robert B. Dalton Endowment Fund; Dr. William Crisp and Mrs. Anita Crisp; and Dr. John C. Budzinski. We also thank the Armada de Chile (Capitán Fernando Mingram López, Capitán Rafael Mac-Kay Backler, and Capitán Roberto Granham Poblete); Drs. Ernest Hamel, and Ron Nieman; and Felicia Craciunescu, Natalie Fuller, Christine Weber, and Lee Williams for other helpful assistance.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Dr. David G. I. Kingston of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University for his pioneering work on bioactive natural products.

Dedicated also to Diane Middlebrook Djerassi (1939–2007), a great humanities scholar.

References and Notes

- 1.(a) Amagata T, Minoura K, Numata A. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1384–1388. doi: 10.1021/np0600189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Asolkar RN, Jensen PR, Kauffman CA, Fenical W. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1756–1759. doi: 10.1021/np0603828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin GDA, Tan LT, Jensen PR, Encarnación Dimayuga R, Fairchild CR, Raventos-Suarez C, Fenical W. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1406–1409. doi: 10.1021/np060621r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Capon RJ, Stewart M, Ratnayake R, Lacey E, Gill JH. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1746–1752. doi: 10.1021/np0702483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Stierle DB, Stierle AA, Patacini B. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1820–1823. doi: 10.1021/np070329z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Linington RG, Edwards DJ, Shuman CF, McPhail KL, Matainaho T, Gerwick WH. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:22–27. doi: 10.1021/np070280x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hughes CC, Prieto-Davo A, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Org Lett. 2008;10:629–631. doi: 10.1021/ol702952n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Rungprom W, Siwu ERO, Lambert LK, Dechsakulwatana C, Barden MC, Kokpol U, Blanchfield JT, Kita M, Garson MJ. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:3147–3152. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Cruz LJ, Martínez Insua M, Pérez Baz J, Trujillo M, Rodriguez-Mias RA, Oliveira E, Giralt E, Albericio F, Cañedo LM. J Org Chem. 2006;71:3335–3338. doi: 10.1021/jo051600p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu J, Takasaki A, Kobayashi H, Oda T, Yamada J, Mangindaan REP, Ukai K, Nagai H, Namikoshi M. J Antibiot. 2006;59:451–455. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jang JH, Kanoh K, Adachi K, Shizuri Y. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1358–1360. doi: 10.1021/np060170a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Oh DC, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8625–8628. [Google Scholar]; (e) Krick A, Kehraus S, Gerhäuser C, Klimo K, Nieger M, Maier A, Fiebig HH, Atodiresai I, Raabe G, Fleischhauer J, König GM. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:353–360. doi: 10.1021/np060505o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kito K, Ookura R, Yoshida S, Namikoshi M, Ooi T, Kusumi T. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:2022–2025. doi: 10.1021/np070301n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Sun Y, Tian L, Huang J, Ma HY, Zheng Z, Lv AL, Yasukawa K, Pei YH. Org Lett. 2008;10:393–396. doi: 10.1021/ol702674f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Pontius A, Mohamed I, Krick A, Kehraus S, König GM. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:272–274. doi: 10.1021/np0704710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Alvarado C, Díaz E, Guzmán Á. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:603–607. [Google Scholar]; (b) Linington RG, González J, Ureña LD, Romero LI, Ortega-Barría E, Gerwick WH. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:397–401. doi: 10.1021/np0605790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) An T, Kumar TKS, Wang M, Liu L, Lay JO, Jr, Liyanage R, Berry J, Gantar M, Marks V, Gawley RE, Rein KS. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:730–735. doi: 10.1021/np060389p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zainuddin EN, Mentel R, Wray V, Jansen R, Nimtz M, Lalk M, Mundt S. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1084–1088. doi: 10.1021/np060303s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Taori K, Matthew S, Rocca JR, Paul VJ, Luesch H. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1593–1600. doi: 10.1021/np0702436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kubota T, Endo T, Takahashi Y, Tsuda M, Kobayashi J. J Antibiot. 2006;59:512–516. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi J, Kubota T. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:451–460. doi: 10.1021/np0605844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsuda M, Oguchi K, Iwamoto R, Okamoto Y, Fukushi E, Kawabata J, Ozawa T, Masuda A. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1661–1663. doi: 10.1021/np0702537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Oguchi K, Tsuda M, Iwamoto R, Okamoto Y, Endo T, Kobayashi J, Ozawa T, Masuda A. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1676–1679. doi: 10.1021/np0703085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Suwan S, Isobe M, Ohtani I, Agata N, Mori M, Ohta M. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1995:765–775. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nagai S, Okimura K, Kaizawa N, Ohki K, Kanatomo S. Chem Pharm Bull. 1996;44:5–10. doi: 10.1248/cpb.44.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kuroda J, Fukai T, Konishi M, Uno J, Kurusu K, Nomura T. Heterocycles. 2000;53:1533–1549. [Google Scholar]; (d) Stenfors Arnesen LP, Fagerlund A, Granum PE. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:579–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Rheims H, Frühling A, Schumann P, Rohde M, Stackebrandt E. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:795–802. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cabaj A, Palínska K, Kosakowska A, Kurlenda J Oceanologia. 2006;48:525–543. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pettit GR, Hu S, Knight JC, Chapuis J-C. J Nat Prod. under revision, np-2008-00607x. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCCLS. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard. 5. NCCLS; Wayne, PA: 2000. NCCLS document M7-A5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.SHELXTL-Version 5.1; an integrated suite of programs for the determination of crystal structures from diffraction data Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, 1997. This package includes, among others, XPREP (an automatic space group determination program), SHELXS (a structure solution program via Patterson or direct methods), and SHELXL (structure refinement software).

- 10.Burla MC, Caliandro R, Camalli M, Carrozzini B, Cascarano GL, De Caro L, Giacovazzo C, Polidori G, Spagna R. J Appl Cryst. 2005;38:381–388. [Google Scholar]

- 11.SMART for Windows NT v5.605. Bruker AXS Inc.; 5465 East Cheryl Parkway, Madison, WI: pp. 53711–5373. [Google Scholar]

- 12.XPREP-The automatic space group determination program in the SHELXTL (see ref. 9).

- 13.Blessing RH. Acta Crystallogr. 1995;A51:33–38. doi: 10.1107/s0108767394005726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamer OA, Reimer MLJ. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22141–22147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757–766. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suffness M, Douros J. In: Methods in Cancer Research. DeVita VT, Busch H, editors. XVIA. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 73–126. [Google Scholar]

- 17.CCDC 715993 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 1. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.