Abstract

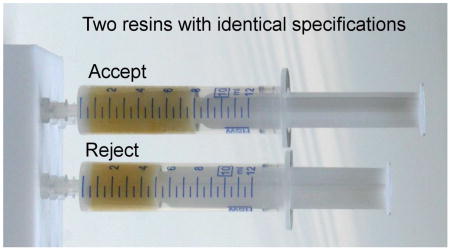

The quality of the most commonly used support for solid phase syntheses, polystyrene resin cross linked with 1% of divinylbenzene, differs considerably even among different lots of resin from the same source. Determination of the swelling capacity of resins before carrying out solid-phase synthesis represents a very simple means of nondestructive pre-synthetic resin characterization.

Introduction

Successful solid-phase organic synthesis (SPOS) is well known to largely depend on the properties and quality of the relevant solid support.1,2 The original Merrifield resin, based on polystyrene (PS) cross-linked with divinylbenzene (DVB), is the solid support of choice for most SPOS applications and versions of this fundamental resin are available from numerous vendors. Being a functionalized co-polymer, analysis of the quality and application reproducibility of individual resin batches is problematic. Practitioners of solid-phase syntheses are thus faced with a problem of obtaining a resin that provides reliable, reproducible, and satisfactory outcomes of polymer-supported transformations. Although resins from different and the same sources may have identical specifications (descriptive/nominal parameters, typically cross-linking, substitution, bead size), they often behave differently in solid-phase syntheses. As pointed out more than fifteen years ago by Pugh and coworkers “The advertised cross-linking, mesh-size, and substitution of commercially available polystyrene resins are rarely correct”.1 Although resin quality has improved, in general, over the years, our experience with currently available resins indicated that the quality and batch to batch reproducibility is still a relevant issue of concern. To address the inequality of “equal” resins we carried out model transformations on several supposedly “identical” resins and arrived at a simple test to address the suitability of a resin for SPOS.

Our aim was to compare performance of the most commonly used support for solid phase syntheses, polystyrene resin cross linked with 1% of divinylbenzene, from different lots and suppliers. Unlike numerous reports that compared various kinds of solid supports in order to identify resin parameters relevant for particular and sometimes diverse synthetic needs,3–7 we compared resins that had identical specifications but were either provided by different suppliers or originated from different lots.

Results and discussion

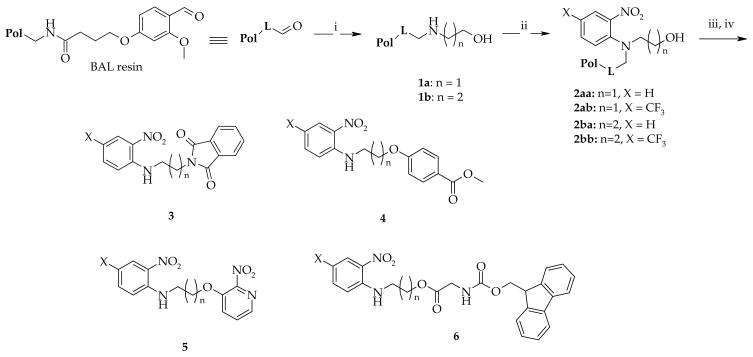

To compare resins, we carried out a synthetic sequence developed for traceless solid-phase synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles.8,9 The first two steps, portrayed in Scheme 1, included reductive amination of the backbone amide linker (BAL) resin followed by reaction with aryl fluorides. In order to expand the diversity of compounds made, we included amino alcohols in representative reductive amination reactions. In the next step, we transformed the individual alcohols to the corresponding amines, ethers and esters by Mitsunobu reactions with phthalimide, phenols, and acids, respectively. Typically, these reactions were complete within 1h. When performing the reactions using a new batch of resin obtained from the same vendor, we observed incomplete conversion.10

Scheme 1. Solid-phase synthesis of model compounds.

Reagents and conditions: (i) amine, 10% AcOH/DMF, overnight, then NaBH(OAc)3, 5 h; (ii) 1-fluoro-2-nitrobenzenes, DIEA, DMSO, overnight, 80 °C for compounds 2aa and 2ba, ambient temperature for 2ab and 2bb; (iii) for reaction conditions see experimental part; (iv) 50% TFA in DCM, 1h.

To determine whether the observed reactivity differences were not just due to resin variation from a single source, we acquired two additional resins from different sources (Table 1) and carried out a set of model reactions using identical polymer-supported intermediates prepared from all four resins. Using reported procedures,9 we prepared four different resin-bound intermediates 2 that differed by the length of side-chain bearing the hydroxyl group and electronic properties of the aromatic ring. Polymer-supported alcohols 2 were reacted with phthalimide, methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate, 3-hydroxy-2-nitropyridine and Fmoc-Gly-OH under Mitsunobu conditions.

Table 1.

Specifications of aminomethyl polystyrene – 1% divinylbenzene resins

| Resin | Loading [mmol/g] | Bead size [mesh] | Swelling in DCM [mL/g] |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.78 | 100–200 | 5.5 |

| B | 0.88 | 100–200 | 7.8 |

| C | 0.90 | 100–200 | 8.1 |

| D | 1.28 | 200–400 | 12.5 |

After each reaction, a sample of resin was treated with TFA in DCM to release the resin-bound components generated. Conversion to products 3 to 6 was determined by LCMS analyses of cleaved samples. The presence of the 2-nitroaniline moiety in all of the compounds provided an internal calibration that allowed simple quantification by integration of LC traces at 440 nm. The results are summarized in Table 2. Data indicated that in reactions using resins that swelled to less than 7 mL/g of dry resin, a substantial amount of starting material 2 was recovered. On the other hand, bead size and loading did not exhibit any significant effect on reaction rate. The Mitsunobu reaction with resin-bound alcohol 2 synthesized on resin A was not complete even after overnight reaction.

Table 2.

Conversion of resin-bound alcohols 2 with model substrates

| Resin | 3aa | 3ab | 4aa | 4ab | 5ba | 6aa | 6ab | 3ba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 63% | 45% | 77% | 63% | 60% | 59% | 53% | 76% |

| B | 85% | 93% | 97% | 88% | 95% | 90% | 89% | 93% |

| C | 95% | 95% | 97% | 93% | NT | 98% | 96% | 96% |

| D | 86% | 92% | 97% | 90% | NT | 97% | 96% | 97% |

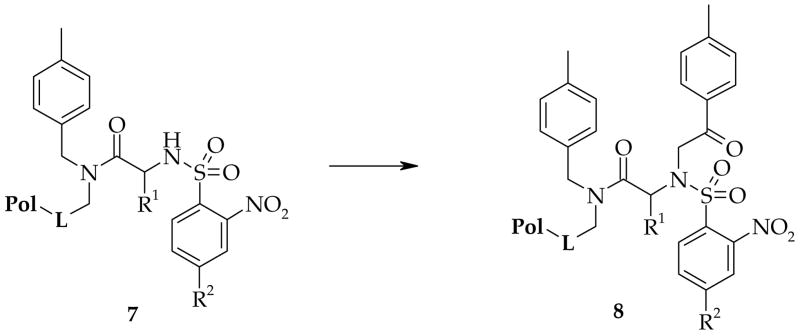

Unrelated chemical transformations that also showed substantially reduced reaction rates with resin A included alkylation of nitrobenzenesulfonamides 7 with bromoketones (Scheme 2). Table 3 compares conversion of resin-bound sulfonamides 7 to alkylated species 8 using resins A and B.

Scheme 2. Alkylation of nitrobenzenesulfonamides with a bromoketone.

Reagents and conditions: 0.5 M 2-bromo-4′-methylacetophenone, 1 M DIEA in DMF, overnight

Table 3.

Comparison of resins A and B in alkylation reaction

| Resin | Swelling DCM | Loading [mmol/g] | Compound | Temperature | R1 | R2 | Conversion [%] | Purity [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5.5 | 0.78 | 8ab | RT | H | NO2 | 75 | 70 |

| A | 5.5 | 0.78 | 8bb | RT | CH3 | NO2 | 70 | 70 |

| B | 7.8 | 0.88 | 8ab | RT | H | NO2 | 99 | 97 |

| B | 7.8 | 0.88 | 8bb | RT | CH3 | NO2 | 99 | 97 |

| A | 5.5 | 0.78 | 8aa | RT | H | H | 20 | ND |

| A | 5.5 | 0.78 | 8aa | 40°C | H | H | 95 | ND |

| B | 7.8 | 0.88 | 8aa | RT | H | H | 96 | ND |

In all model experiments, the polymer-supported intermediates prepared from resin A provided unsatisfactory transformation to products. Interestingly enough, resins A and B originated from the same vendor, they differed just by lot number. We were obviously interested in finding an easily observable parameter that would indicate differences between resin A and the other resins. Our experiments have shown that transformation of model reactions correlated with resin swelling. We measured resin swelling in DCM and the results are listed in Table 1. Swelling differed considerably even among different lots of resin from the same source.

The effect of resin swelling has been reviewed2 and efficient swelling of 1%-DVB cross-linked PS resins is known to be essential for reactivity and, reportedly, significantly diminished swelling caused synthetic problems in peptide coupling.11–14 We suspect that the low swelling capacity of resin is caused by higher level of cross linking.1 Higher cross-linking is known to increase half-lives of polymer-supported reactions.15 Unfortunately, resin suppliers typically do not provide the swelling capacity of resins.

To conclude our observations, determination of the swelling capacity of resins before carrying out solid-phase synthesis represents a very simple means of nondestructive pre-synthetic resin characterization. Our results indicated that swelling in DCM greater that 7 mL per 1 g of dry resin provided satisfactory conversion to products in all model reactions. Lower swelling substantially reduced the conversion rate. Resin suppliers are encouraged to include swelling capacity as one of the specification parameters that characterizes each batch of resin.

Experimental section

Aminomethyl polystyrene – 1% divinylbenzene resins were obtained from NovaBiochem (San Diego, CA, www.emdbiosciences.com), Advanced ChemTech (Louisville, KY, www.peptide.com), and TCI (Portland, OR, http://www.tciamerica.com/). Resins A and B were obtained from one vendor and they differed by a lot number. Resins C and D were obtained from two other vendors. Resin-bound intermediates 2 and 7 were prepared according the reported protocols.9,16

Compounds 3, 4 and 6

Resin-bound intermediates 2 prepared from resins A, B, C and D, 50 mg, were washed with dry NMP. A solution of phthalimide (for compounds 3), methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (for compounds 4), and Fmoc-Gly-OH (for compounds 6) (0.25 mmol) and PPh3 (0.25 mmol, 66 mg) in 1 mL of dry NMP was prepared and diisopropylazodicarboxylate (DIAD, 0.25 mmol, 49 μL) was added. The solution was added to the resin and the resin slurry was shaken for 30 min at ambient temperature.

Compounds 5

Resin-bound intermediates 2ba prepared from resins A and B, 500 mg, were washed with dry THF. A solution of 3-hydroxy-2-nitropyridine (2.5 mmol, 350 mg) and PPh3 (2.5 mmol, 656 mg) in 5 mL of dry THF was chilled and DIAD (2.5 mmol, 484 μL) was added. The solution was added to the resin and the resin slurry was shaken overnight at ambient temperature.

Compounds 8

Resin-bound intermediates 7 prepared from resins A and B, 20 mg, were washed 3 times with DCM and 3 times with DMF. A 0.5 M solution of bromoketone and 1 M DIEA in 2 mL of DMF were added. The resin slurry was shaken overnight at ambient temperature.

Analysis of reaction mixtures

After washing with reaction solvent and DCM, a sample of resin was treated with 50% TFA in DCM for 30 min, the cleavage cocktail was evaporated with a stream of nitrogen, the crude reaction mixture was extracted with methanol, and the reaction mixture components were identified (MS) and quantified (LC) by LCMS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Notre Dame, and the NIH (GM075855, GM079576, and R01GM075855). We gratefully appreciate the use of the NMR facility at the University of Notre Dame.

References

- 1.Pugh KC, York EJ, Stewart JM. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1992;40:208–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan B. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 1998;1:215–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meldal M, Auzanneau FI, Hindsgaul O, Palcic MM. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1994:1849–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Yan B. J Org Chem. 1998;63:4092–4097. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rademann J, Grotil MM, Meldal M, Bock K. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5459–5466. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alesso SM, Yu ZR, Pears D, Worthington PA, Luke RWA, Bradley M. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7163–7169. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mogemark M, Gardmo F, Tengel T, Kihlberg J, Elofsson M. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2004;2:1770–1776. doi: 10.1039/b404802d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Krchňák V. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:7633–7636. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krchňák V, Smith J, Vagner J. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 2001;66:1078–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soural M, Bouillon I, Krchňák V. J Comb Chem. 2008;10 doi: 10.1021/cc800072g. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent SBH. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:957–989. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thaler A, Seebach D, Cardinaux F. Helv Chim Acta. 1991;74:628–643. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krchňák V, Flegelova Z, Vagner J. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1993;42:450–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1993.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam JP, Lu YA. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:12058–12063. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rana S, White P, Bradley M. J Comb Chem. 2001;3:9–15. doi: 10.1021/cc0000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krchňák V, Slough GA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:4289–4291. [Google Scholar]