Abstract

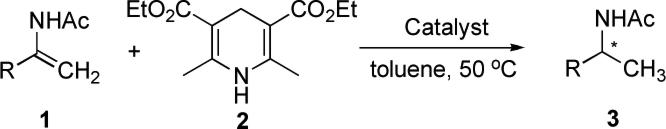

A highly enantioselective hydrogenation of enamides catalyzed by a dual chiral-achiral acid system was developed. By employing a sub-stoichiometric amount of a chiral phosphoric acid and acetic acid, catalyst loadings as low as 1 mol% of the chiral catalyst were sufficient to provide excellent yield and enantioselectivity of the reduction product.

Enantioselective hydrogenation is one of the key transformations to produce chiral compounds in academia and in the chemical industry.1 As a new direction in this research field, enantioselective hydrogenation catalyzed by organocatalysts with Hantzsch esters as the reducing agent has emerged as an attractive strategy due due to its environmentally benign nature.2 Recently, chiral Brønsted acids3 were reported as highly efficient catalysts for the hydrogenation of ketimines, α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and nitroolefins by the research groups of Rueping, List, MacMillan and others.4 Likewise, our recent interest in chiral phosphoric acid-catalysis5 included a report whereby α-imino esters could be reduced in the presence of a VAPOL phosphoric acid-catalyst (A2) to prepare chiral α-amino acid esters with excellent enantioselectivities.5a

Although the reductive amination of ketones and the hydrogenation of ketimines catalyzed by chiral Brønsted acids were achieved in high enantioselectivities, these reactions were limited primarily to reactants derived from aniline and its analogues. As a result, the deprotection of the aromatic group to reveal the amino group can be relatively difficult, requiring somewhat harsh reaction conditions such as those methods that use ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN), rendering these methods less synthetically appealing (eq. 1, Scheme 1). Attractive features of enamides are their relative stability and ease in handling. Additionally, when considering N-acyl enamide substrates, the acyl group of the reduction product can be easily removed under standard procedures in good yield. Therefore, due to these considerations such enamide precursors have become popular substrates for preparing chiral amines through standard metal-catalyzed hydrogenation.1 Herein we would like to report our results on the asymmetric hydrogenation of enamides with high enantioselectivity using chiral phosphoric acid catalysis (eq. 2, Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

We initiated our studies on the hydrogenation of enamide 1a by using the achiral phenylphosphinic acid (A1) as the catalyst, with 1.1 equivalents of Hantzsch ester dihydropyridine 2 as the reducing agent. We were pleased to find that in the presence of 10 mol % of A1, at ambient temperature, the reaction took place smoothly in an argon atmosphere to provide a 95% isolated yield of the desired product amide 3a (entry 1, Table 1). However, when we replaced the achiral catalyst A1 with chiral phosphoric acids (A2-A4) under similar conditions (5 mol % catalyst, rt), the reactions were sluggish and no product was detected by TLC after 24h (not shown in Table 1). However, when we raised the temperature to 50 □, we were pleased to find that catalyst A3 allowed for a 92% isolated yield of amine 3a with 91% ee (entry 4), while acids A2 and A3 gave very low yields of the desired product (< 15% yield by 1H NMR, entries 2 and 3). Further screening of solvents showed that non-coordinating solvents solvents like toluene were ideal (entry 4), while other coordinating solvents such as ether, THF, and the protic solvent methanol gave very sluggish reactions (entries 5−8).

Table 1.

Reaction conditions for the asymmetric reduction of enamides.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst (mol%) | solvent | temp (¼ C) | time (h) | yield (%)a | ee (%) |

| 1 | A1 (10) | toluene | rt | 17 | 95 | 0 |

| 2 | A2 (5) | toluene | 50 | 36 | <15b | nd |

| 3 | A3 (5) | toluene | 50 | 36 | <10b | nd |

| 4 | A4 (5) | toluene | 50 | 15 | 92 | 91 |

| 5 | A4 (5) | Et20 | 50 | 22 | <13b | nd |

| 6 | A4 (5) | THF | 50 | 22 | < 5b | nd |

| 7 | A4 (5) | EtOAc | 50 | 48 | < 15b | nd |

| 8 | A4 (5) | MeOH | 50 | 48 | < 5b | nd |

| 9 | A4 (2) | toluene | 50 | 41 | 85 | 91 |

| 10 | A4 (1) | toluene | 50 | 117 | 39 | 90 |

| 11 | A4 (1)+ AcOH(10) | toluene | 50 | 15 | 97 | 91 |

| 12 | AcOH(10) | toluene | 50 | 17 | 0b | nd |

Isolated yields

Yield determined by 1H NMR.

ce values determined by Chiral-HPLC (see Supporting Information).

Efforts toward decreasing the catalyst loading led to lower yields but no loss in ee was found. For example, with 2 mol % of catalyst A3, the yield of 3a was 85% (entry 9), but with a catalyst loading of 1 mol %, the yield of 3a decreased to 39% even with a longer reaction time (entry 10). Believing that a reactive iminium was the intermediate of this reaction we reasoned that decreasing the catalyst loading probably lead to a low concentration of iminium, and thus a slow reaction. Our working hypothesis assumed therefore that this iminium formation was the rate determining step (eq. 3). In order to develop an efficient hydrogenation reaction with a low catalyst loading, we considered the use of a dual catalytic chiral-achiral acid system. We believed that a suitable achiral acid should be able to facilitate iminium formation, while being inactive in the hydrogenation step, where our chiral phosphoric acid, which had already demonstrated enantioselectivity, could remain active (eq. 4).

As expected, with 1 mol % of catalyst (S)-A4 and 10 mol % of acetic acid as a cocatalyst, the reaction was completed within 15 hours to provide the desired product 3a in 97% isolated yield and with 91% ee (entry 11, Table 1). A study on the background reaction with acetic acid as the only catalyst further confirmed our hypothesis that the acetic acid was inactive for the hydrogenation of enamide 1a (entry 12). We would like to note that a similar strategy was also reported by Rueping's group. Rueping and coworkers successfully utilized two Brønsted acids as the catalyst for the asymmetric synthesis of isoquinuclidines.6

Our optimized reaction conditions for the enantioselective organocatalytic hydrogenation of enamides were determined to be the following: 1 mol % of chiral phosphoric acid A4, 10 mol % AcOH, 50 □, with a ratio of enamide 1 and Hantzsch ester 2 set at 1/1.1 eq. and toluene as the solvent. Under the general conditions above, we evaluated various enamide substrates and the results are summarized in Table 2. In order to demonstrate the advantages of the dual-acid catalytic system, we also conducted the corresponding reactions catalyzed by the single chiral phosphoric acid (S)-A4. As shown in Table 2, the dual-acid catalytic system significantly accelerated the hydrogenation reaction. For example, enamide 1b bearing a para-methyl group on the phenyl ring gave only 53% yield and 91% ee of the product 3b even when the reaction was run for 3 days (entry 3), while with the addition of 10 mol % of acetic acid, the reaction provided a 93% isolated yield and 90% ee of the product in 24 h (entry 4). In other cases, the dual-acid catalytic system was also highly efficient, for instance, with aromatic enamides bearing electron-withdrawing groups such as para-chloro (entries 5 and 6), para-fluoro (entries 7 and 8), and para-trifluoromethyl groups (entries 9 and 10) provided similar rate acceleration with good enantioselectivities (87−92% ee). Likewise, the para-methoxy (95% ee; entry 11) and β-naphthyl enamide substrates (92% ee; entry 13) were excellent reaction partners.

Table 2.

Studies on the substrate scope.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | catalysta | time (h) | yield (%)b | ee (%)c |

| 1 | Ph (1a) | A | 117 | 39 | 84(R)(+) |

| 2 | Ph(1a) | B | 15 | 97 | 83(R)(+) |

| 3 | 4-MeC6H4 (1b) | A | 72 | 53 | 91(R)(+) |

| 4 | 4-MeC6H4 (1b) | B | 24 | 93 | 90(R)(+) |

| 5 | 4-ClC6H4(1c) | A | 48 | 71 | 92(R)(+) |

| 6 | 4-ClC6H4 (1c) | B | 17 | 88 | 91(R)(+) |

| 7 | 4-FC6H4 (1d) | A | 72 | 90 | 90(R)(+) |

| 8 | 4-FC6H4 (1d) | B | 17 | 96 | 89(R)(+) |

| 9 | 4-CF3C6H4 (1e) | A | 69 | 74 | 87(R)(+) |

| 10 | 4-CF3C6H4 (1e) | B | 40 | 96 | 87(R)(+) |

| 11 | 4-MeOC6H4 (1f) | A | 15 | 96 | 95(R)(+) |

| 12 | β-naphthyl (1g) | A | 48 | 91 | 94(R)(+) |

| 13 | β-naphthyl (1g) | B | 14 | 99 | 92(R)(+) |

| 14 | α-naphthyl (1h) | A | 94 | 31 | 89(S)(-) |

| 15 | α-naphthyl (1h) | B | 44 | 43 | 78(S)(-) |

| 16 | 3-MeOC6H4 (1i) | A | 47 | 90 | 74(R)(+) |

| 17 | 3-MeOC6H4 (1i) | B | 18 | 98 | 71(R)(+) |

| 18 | 2-MeOC6H4 (1j) | A | 40 | 90 | 42(S)(-) |

| 19 | 2-MeOC6H4 (1j) | B | 15 | 96 | 41(S)(-) |

| 20 | t-Butyl (1k) | A or B | 48 | NRd | NDe |

Catalyst A = A4 (1 mol%); catalyst B = A4 (1 mol%) + AcOH (10 mol%).

Isolated yield.

Determined by chiral HPLC, see Supporting Information for details.

No desired product was detected.

Not analyzed.

A lower enantioselectivity was noted with the α-naphthyl enamide 1h (78% ee; entry 15). It is interesting that in this case the addition of the co-catalyst resulted in a slightly diminished ee. This phenomenon suggested that steric hindrance is an important factor in this hydrogenation reaction and it was further confirmed by other examples. Enamides 1i and 1j, meta- and ortho-substitued arenes gave even lower enantioselectivities as the steric hindance increased (71% ee and 41% ee, entries 17 and 19, respectively. Finally, it should be note that while these conditions allow for the highly selective hydrogenation of aromatic enamides it is ineffective for alaphatic enamides, such as enamide 1k (entry 20). The absolute stereochemistry of all the products were assigned by comparing the optical rotation with the corresponding known amides (see Supporting Information for details).

In order to support our hypothesis that the iminium is an important intermediate of this reduction, a series of 1H NMR experiments was performed. To a solution of 1a in C6D6 was added catalyst A4. It was apparent that new NMR signals grew in after five minutes at room temperature. These peaks were assigned to the following species: acetophenone, acetamide and the corresponding iminium. It was therefore apparent that catalyst A4 can tautomerize the enamide 1a to its imine, then partially decompose this imine. In a separate experiment using acetic acid instead of catalyst A4, nothing happened at room temperature. However, at 50 □ , the corresponding iminium was observed after 3 hours, and only a very small amount of enamide 1a was decomposed. These experiments comfirmed the hypothesis in Scheme 2. Based on the experiments above, a reasonable dual-activation mechanism similar to that reported recently by Goodman is proposed in Scheme 3.7 In the presence of catalyst A4 and the co-catalyst acetic acid, the enamide 1 was tautomerized to the corresponding imine, which was activated by the acid via an iminium intermediate. In the following step, only chiral phosphoric acid A4 was active enough to catalyze the hydrogenation of the imine, while the acetic acid role was probably only to help keep a sufficient concentration of iminium intermediate present since A4 was used in such small quanitities.

Scheme 2.

Function of a dual-acid catalyst system

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for the asymmetric hydrogenation of enamides catalyzed by a dual acid system.

In conclusion, we have described a highly enantioselective hydrogenation reaction of enamides catalyzed by a dual-acid catalyst system. By using a chiral phosphoric acid combined with a catalytic amount of acetic acid as the catalyst, the loading of the chiral phosphoric acid can be as low as 1 mol %, but still provide excellent yield and enantioselectivity for the process. Additionally, we confirmed that the iminium is the intermediate generated and that the achiral co-acid can be used to generate a suitable concentration of iminium for a facile reaction.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Phosphorous based acid catalysts

Acknowledgment

We thank the University of South Florida for generous start-up funds and a New Researcher Award. J.C.A. also thanks the Petroleum Research Fund (PRF 45899-G1) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH GM-082935) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, characterization, chiral HPLC conditions, and spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.a Tang W, Zhang X. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3029. doi: 10.1021/cr020049i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jaekel C, Paciello R. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2912. doi: 10.1021/cr040675a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Brown JM. In: Mechanism of enantioselective hydrogenation. Handbook of Homogeneous Hydrogenation. 2007 De Vries JG, Elsevier CJ, editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: [Google Scholar]

- 2.For reviews, see: Ouellet G, Walji AM, Macmillan DWC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1327. doi: 10.1021/ar7001864.You S-L. Chemistry, an Asian journal. 2007;2:820. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700081.Connon SJ. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:3407. doi: 10.1039/b711499k..

- 3.For reviews with considerable chiral phosphoric acid coverage see: Akiyama T, Itoh J, Fuchibe K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:999.Connon SJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3909. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600529.Akiyama T. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5744. doi: 10.1021/cr068374j.Terada M. Chem. Commun. 2008:4097. doi: 10.1039/b807577h. For recent reports see: Rueping M, Nachtsheim BJ, Moreth SA, Bolte M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:593. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703668.Wang X, List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1119. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704185.Akiyama T, Honma Y, Itoh J, Fuchibe K. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:399.Jiao P, Nakashima D, Yamamoto H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2411. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705314.Jiang J, Yu J, Sun X-X, Rao Q-Q, Gong L-Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:2458. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705300.Xu S, Wang Z, Zhang X, Zhang X, Ding K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:2840. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705932.Chen X-H, Zhang W-Q, Gong L-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5652. doi: 10.1021/ja801034e.Enders D, Narine AA, Toulgoat F, Bisschops T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5661. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801354.Zhang G-W, Wang L, Nie J, Ma J-A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1457.Cheon CH, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9246. doi: 10.1021/ja8041542.Hu W, Xu X, Zhou J, Liu W-J, Huang H, Hu J, Yang L, Gong L-Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7782. doi: 10.1021/ja801755z.Rueping M, Antonchick AP. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1731. doi: 10.1021/ol8003589.Giera D, Sickert M, Schneider C. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4259. doi: 10.1021/ol8017374.Cheng X, Goddard R, Buth G, List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5079. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801173.Sickert Marcel, Schneider Christoph. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3631. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800103.Itoh J, Fuchibe K, Akiyama T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4016. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800770.Terada M, Soga K, Momiyama N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4122. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800232.Rueping M, Antonchick AP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5836. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801435.Rueping M, Theissmann T, Kuenkel A, Koenigs RM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:6798. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802139.Kang Q, Zheng X-J, You S-L. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:3539. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800263.Cheng X, Vellalath S, Goddard R, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15786. doi: 10.1021/ja8071034.Rueping M, Antonchick AP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:10090. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803610..

- 4.For chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed reduction reactions, see: Rueping M, Sugiono E, Azap C, Theissmann T, Bolte M. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3781. doi: 10.1021/ol0515964.Hoffmann S, Seayad AM, List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:7424. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503062.Storer RI, Carrera DE, Ni Y, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:84. doi: 10.1021/ja057222n.Martin NJA, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13368. doi: 10.1021/ja065708d.Hoffmann S, Nicoletti M, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13074. doi: 10.1021/ja065404r.Rueping M, Antonchick AP, Theissmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3683. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600191.Mayer S, List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4193. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600512.Rueping M, Antonchick AP, Theissmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6751. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601832.Zhou J, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7498. doi: 10.1021/ja072134j.Rueping M, Antonchick AP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:4562. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701158.Guo Q-S, Du D-M, Xu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:759. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703925.Rueping M, Theissmann T, Raja S, Bats JW. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1001.Kang Q, Zhao Z–A, You S-L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1657.Kang Q, Zhao Z-A, You S-L. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2031. doi: 10.1021/ol800494r.Martin NJA, Cheng X, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13862. doi: 10.1021/ja8069852..

- 5.a Li G, Liang Y, Antilla JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5830. doi: 10.1021/ja070519w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rowland GB, Zhang H, Rowland EB, Chennamadhavuni S, Wang Y, Antilla JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15696. doi: 10.1021/ja0533085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rowland GB, Rowland EB, Liang Y, Antilla JC. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2609. doi: 10.1021/ol0703579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li G, Rowland GB, Rowland EB, Antilla JC. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4065. doi: 10.1021/ol701881j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Liang Y, Rowland EB, Rowland GB, Perman JA, Antilla JC. Chem. Commun. 2007;43:4477. doi: 10.1039/b709276h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Rowland EB, Rowland GB, Rivera-Otero E, Antilla JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12084. doi: 10.1021/ja0751779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Li G, Fronczek FR, Antilla JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12216. doi: 10.1021/ja8033334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rueping M, Azap C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:7832. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For an excellent theoretical study on a related mechanism, see: Simon L, Goodman JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8741. doi: 10.1021/ja800793t..

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.