Conspectus

“The true creator is necessity, who is the mother of our invention.” - Plato

IUPAC defines chemoselectivity as “the preferential reaction of a chemical reagent with one of two or more different functional groups,” a definition which describes in rather understated terms the single greatest obstacle to complex molecule synthesis. Indeed, efforts to synthesize natural products often become case studies in the art and science of chemoselective control, a skill which nature has practiced deftly for billions of years, but man has yet to master. Confrontation of one or perhaps a collection of functional groups that are either promiscuously reactive or stubbornly inert has the potential to unravel an entire strategic design. One could argue that the degree to which chemists can control chemoselectivity pales in comparison to the state of the art in stereocontrol. In this account, we hope to illustrate how the combination of necessity and tenacity leads to the invention of new chemoselective chemistry for the construction of complex molecules.

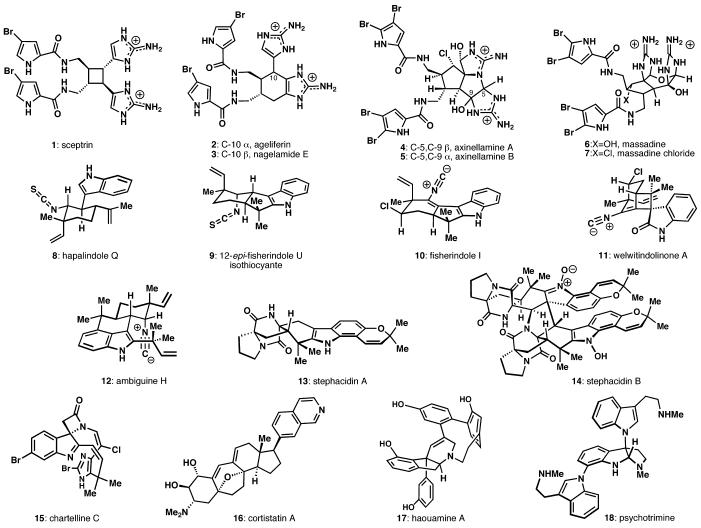

In our laboratory, a premium is placed upon selecting targets that would be difficult or impossible to synthesize using traditional techniques (see Figure 1). The successful completion of such molecules demands a high degree of innovation, enabling the discovery of new reactivity and principles for controlling chemoselectivity. In devising an approach to a difficult target, bond disconnections are chosen primarily to maximize skeletal simplification, but especially when the proposed chemistry is poorly precedented or completely unknown. By choosing such a strategy, rather than adapting an approach to fit known reactions, innovation and invention become the primary goal of the total synthesis. Delivery of the target molecule in a concise and convergent manner is the natural consequence of such endeavors and invention becomes a prerequisite for success.

Figure 1.

Representative natural products synthesized in the Baran research group (2003 - 2008).

Introduction

The instinctual desire of organic chemists to take up the challenge of synthesizing the most daunting natural products has traditionally proven to be a major driving force for innovation in synthetic chemistry. New techniques developed during the pursuit of one target then find application in completely unrelated problems, enabling the synthesis of other previously inaccessible natural products. History is replete with examples of synthetic methods inspired by a single target or class of targets that have become standard selections in a chemist's repertoire.1

In the course of planning and executing the syntheses described in this account (Figure 1), we have found that there are several guidelines that are particularly useful in devising viable synthetic approaches to target molecules: (1) redox reactions which do not form carbon-carbon or carbon-heteroatom bonds should be minimized, (2) the percentage of C-C bond forming and strategic C-C bond breaking events relative to the total number of steps in a synthesis should be maximized, (3) disconnections should be chosen to maximize convergency, (4) the overall oxidation level of intermediates should either linearly escalate or remain constant during assembly of the molecular framework, (except in cases where there is a strategic benefit, such as asymmetric reduction), (5) where possible, cascade or tandem reactions should be designed and incorporated to maximize structural change per step, (6) the innate reactivity of functional groups should be exploited to reduce the number of (or perhaps even eliminate) protecting groups, (7) effort should be spent on the invention of new methodology to facilitate the aforementioned criteria and to uncover new aspects of chemical reactivity, (8) if the target molecule is of natural origin, known or proposed biosynthetic pathways should only be incorporated to the extent that they aid the above considerations.2 Each of these principles, some to a greater extent than others, require one to address the ever present issue of chemoselectivity.3 With regards to the issue of protecting groups, we would submit that these artificial agents, while often enabling in the synthesis of certain classes of molecules, are the direct offspring of chemists' inability to control chemoselectivity.

The degree to which these guidelines apply to a given synthesis of course varies considerably with the structure of target. Deviations from the ideal implementation of these guidelines may also be necessitated by experimental difficulties encountered during the course of the synthesis. In the examples discussed in this Account, we seek to illustrate how the application of these guidelines has allowed for considerable innovation during the synthesis of complex natural products.

Pyrrole-Imidazole Alkaloids

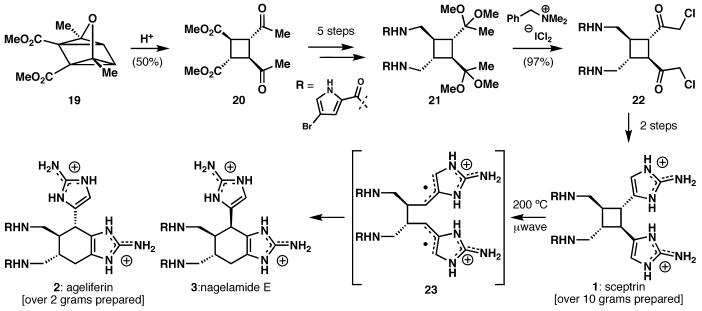

The pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids are a series of natural products derived from marine sponges that share hymenidin as a common biosynthetic precursor.4 Within this class of alkaloids, sceptrin (1) was selected as the initial target because of its presumed role as a biosynthetic precursor to other members of the class. Although sceptrin appears to be a [2+2] dimer of hymenidin, the isolation chemists reported their inability to dimerize hymenidin under a variety of conditions. Consequently, a strategy centered upon the initial formation of the molecule's cyclobutane core was selected. This was accomplished by fragmentation of oxaquadricyclane 19 (Scheme 1), which was obtained from 2,5-dimethyl furan and dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate. Standard functional group manipulations then led to intermediate 21, which lacked only the 2-aminoimidazole units of sceptrin. The installation of these heterocycles required halogenation of the methyl ketones, a seemingly straightforward task complicated by the propensity of the bromopyrroles to react with electrophilic halogenating reagents. The potential for halogenation at the methine carbons α to the ketones and for multiple halogenation of the methyl groups posed further selectivity challenges. This obstacle was eventually surmounted by the use of benzyltrimethylammonium dichloroiodate to chlorinate ketal 21.

Scheme 1.

An oxaquadricyclane fragmentation leads to the first total synthesis of sceptrin (1) and an unusual cyclobutane fragmentation delivers the cyclohexyl pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids ageliferin (2) and nagelamide E (3).

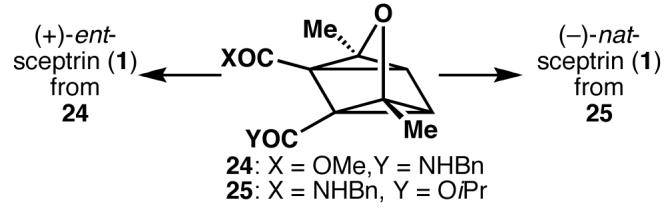

While the fragmentation of oxaquadricyclane 19 provided a facile means to acquire cyclobutane 20 in racemic form, the ill-defined mechanism of this reaction rendered prospects of an enantioselective synthesis uncertain. Nonetheless, attempts were made to effect an enantioselective synthesis by differentiating the enolization energies of the two carbonyl groups. The use of an enzymatic desymmetrization allowed access to oxaquadricyclanes 24 and 25. After some modification of the fragmentation conditions, 25 was elaborated to the natural enantiomer of sceptrin and 24 to the unnatural enantiomer, culminating in an approach which solved a problem of enantioselectivity by addressing chemoselectivity.5

The widely held belief that ageliferin (2, Scheme 1) was the product of a [4+2] dimerization of hymenidin notwithstanding, we proposed an alternative biosynthesis in which sceptrin served as a direct biosynthetic precursor to ageliferin via a [1,3] rearrangement and tautomerization. By heating sceptrin acetate to 195 - 200 °C in water using a microwave reactor, ageliferin was obtained in 50% yield, along with 28% of its epimer 3, which was at a later date identified as a natural product and named nagelamide E, and 12% recovered sceptrin.6 Computational studies indicated that this rearrangement likely proceeds by a radical scission of the cyclobutane, followed by 6-endo recombination of the diradical (23) and tautomerization to form ageliferin.6

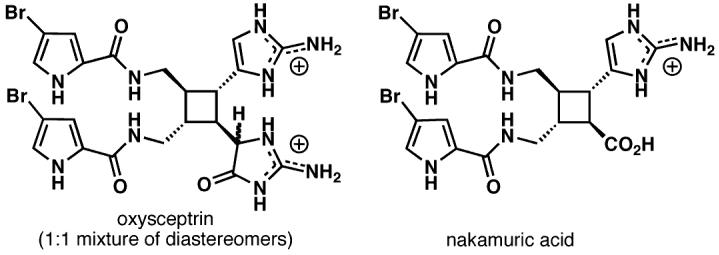

Not surprisingly, sceptrin also served as a synthetic precursor to oxysceptrin and nakamuric acid (Figure 2).6 These presumably biomimetic transformations relied on the ability to chemoselectively oxidize the aminoimidazole in preference to the bromopyrrole. These studies have led to a robust route which delivers 1 and 2 in multi-gram quantities using a single protecting group and one chromatographic separation.

Figure 2.

Oxysceptrin and nakamuric acid: natural products obtained by chemoselective oxidation of sceptrin (1).

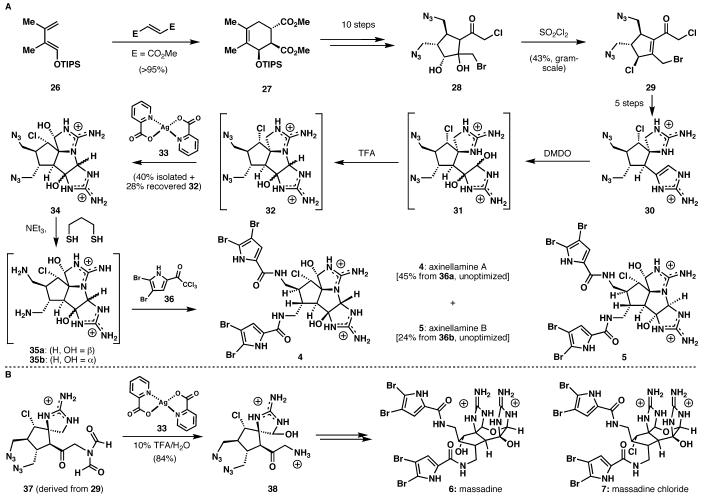

Having completed sceptrin, ageliferin, and their derivatives, our attention turned to the most complicated alkaloids in this class, typified by the axinellamines and massadines (4-7). These challenging alkaloids are centered around a hexasubstituted cyclopentane core that possesses five of the molecule's eight total contiguous stereocenters. In addition, the ten nitrogen atoms present in these molecules render them highly polar and complicate seemingly routine reactions and purifications.

This synthesis began with a Diels-Alder reaction between siloxy diene 26 (Scheme 3A) and dimethyl fumarate to give cyclohexene 27.7,8 The configuration of these three stereocenters would be used to set the configuration of the five remaining stereocenters in the molecule. After some functional group manipulations, dehydration of the tertiary alcohol of 28 or similar intermediates proved unexpectedly difficult, as did conversion of the secondary alcohol to the requisite chloride. A cascade reaction was therefore developed to solve both of these problems simultaneously; upon treatment with sulfuryl chloride, diol 28 gave chloro enone 29 in 43% yield on multi-gram scale. Elaboration of 29 installed the 2-aminoimidazole and spiro guanidine units. The 2-aminoimidazole of 30 was then oxidized with dimethyldioxirane (to give 31) and the axinellamine core was closed by exposure to trifluoracetic acid (forming 32 as a mixture of two diastereomers).

Scheme 3.

Incorporation of a strategically-simplifying late-stage chemoselective intermolecular oxidation facilitates the total synthesis of axinellamines A (4) and B (5), massadine (6), and massadine chloride (7).

At this point, the most crucial transformation remaining was the oxidation of the spiro methylene unit to the aminal oxidation state. This would require late-stage intermolecular chemoselective oxidation next to only one of the six guanidine nitrogens in the molecule. Although there were a number of reports describing the oxidation of amines to imines, there was no precedent for oxidizing a guanidine to an aminal of this type. After considerable experimentation, silver(II) picolinate (33) was found to be the optimum reagent for the oxidation of 32, giving a 40% yield of 34 as a 3:1 mixture of diastereomers (which correspond to axinellamines A and B) and 28% of recovered 32. The diastereomers of 34 were separated by the use of preparative HPLC.

The reduction of the azides in 34 to the amines proved difficult, but a solution was found by using 1,3-propanedithiol and triethylamine. Completion of the axinellamines then required acylation of the two newly formed primary amines of 35a/b in the presence of the six unprotected guanidine nitrogens. The use of trichloroketone 36 and Hünig's base in DMF allowed us to capitalize on the difference in nucleophilicity between primary amines and guanidines and gave axinellamine A in 45% from the major diastereomer of 35a. Use of the minor diastereomer (35b) gave 24% of axinellamine B under identical conditions. The synthesis of massadine (6, Scheme 3B) relied upon the chemoselective silver-mediated oxidation which was dramatically improved by conducting the reaction in a TFA/water solution. Indeed, the yield of the oxidation of 32 to 34 could be improved to 77%. This robust, reliable, and scalable procedure allowed the evaluation of multiple routes to the massadines. Ultimately, 37 (derived from 29) was oxidized afford 38 in 84% isolated yield. This intermediate could then be elaborated into massadine (6) and massadine chloride (7).9 The ability to manipulate and chemoselectively react intermediates containing six or more unprotected nitrogen atoms proved key in completing the first total synthesis of the axinellamines and massadines.10

Indole Alkaloids from Cyanobacteria

The Stigonematacae family of cyanobacteria has produced over 60 members of an architecturally complex family of indole alkaloids that includes the hapalindoles, fischerindoles, welwitindolinones, and ambiguines. These alkaloids consist of an indole attached to a terpene-derived carbocyclic unit. The members of these families vary in the degree and position of functionalization and cyclization, with the ambiguines also bearing an additional terpene unit.

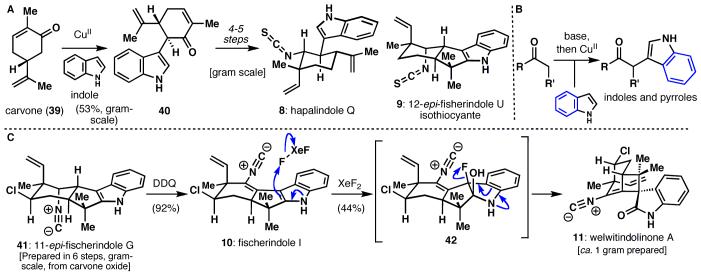

Given the large number of known members of this family, the retrosynthetic plan was heavily influenced by presumed biosynthetic relationships. The simplest members of the family were targeted first, with the intention of using them as synthetic precursors of more complex members. Hapalindole Q (8)11 was therefore selected as the initial target. Noting the similarity of the terpene-derived fragment to the readily available carvone (39, Scheme 4A), it was quickly recognized that the most direct approach to this alkaloid would involve the coupling of indole to a carvone-derived fragment. Unfortunately, the functional group arrangement of the targets did not readily lend itself to the use of traditional methods, such as palladium catalyzed coupling. Although a suitable substrate likely could have been found, this would have required multiple functional group manipulations. A chemoselective method was therefore sought to effect the direct coupling of indole and carvone.

Scheme 4.

Another strategically simplifying transformation, indole-enolate oxidative coupling, provides an entry into the hapalindole and fisherindole alkaloids, including welwitindolinone A (11).

Drawing inspiration from the oxidative coupling of enolates, indole and carvone were deprotonated using LHMDS and then exposed to a variety of oxidants. Copper(II)-2-ethylhexanoate proved to be the optimum reagent for this transformation, giving a 53% yield of coupled product 40 on a multi-gram scale. This compound could then be elaborated to the natural products hapalindole Q (10) and 12-epi-fisherindole U isothiocyantate (11) in four and five steps, respectively.12 In addition to allowing access to these natural products in remarkably concise and practical fashion, this powerful reaction proved applicable to a wide variety of substrates, including ketones, amides, esters, and pyrroles (Figure 4B).13,14 This interesting type of reactivity has also been extended to allow for the first practical intermolecular enolate heterocouplings (see next section).15

Having established the viability of the oxidative indole-carbonyl coupling, welwitindolinone A (11, Scheme 4C)16 was selected as the next target in this family. We hypothesized that welwitindolinone A (11) arises biosynthetically by an oxidative ring contraction of fisherindole I (10), so this natural product was prepared in a manner similar to 9, using a terpene portion derived from carvone oxide.17 After arriving at 11-epi-fischerindole G (41) in six steps (gram-scale), benzylic oxidation took place readily with DDQ to afford fischerindole I (10). Considerable experimentation led to the finding that XeF2 can chemoselectively fluorohydroxylate 10 to give 11 as a single diastereomer in 44% yield of presumably via 42. It should be noted that other sorts of oxidants such as those based on electrophilic sources of Br, Cl, and I led to considerably lower yields and were not scalable due to competing reaction with the sensitive isonitrile moiety. In contrast, use of XeF2 has enabled the procurement of ca. one gram of enantiopure welwitindolinone A (11).18

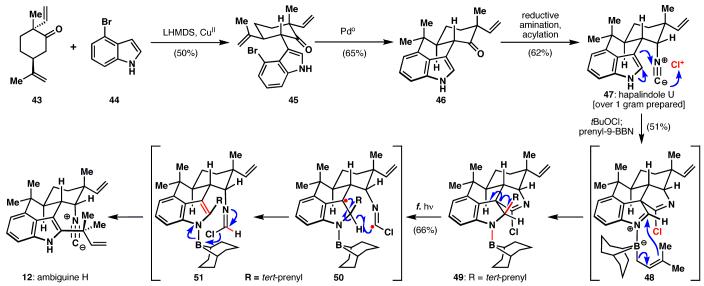

Ambiguine H (12, Scheme 5) was selected as the next target in this series of alkaloids. It was anticipated that this natural product could be accessed by prenylation of hapalindole U (47). This natural product was conveniently accessed by an oxidative coupling of 4-bromoindole (44) and a terpene-derived ketone unit (43), followed by a Heck cyclization to install the central cyclohexane ring yielding tetracycle 46. Stereoselective reductive amination and isonitrile formation led cleanly to over one gram of hapalindole U (47). Attempted prenylation of 47 under Danishefsky's conditions (tBuOCl followed by 9-BBN) rather unexpectedly produced pentacyclic compound 49. While there was a pressing desire to change course and pursue alternative strategies that would circumnavigate this reactivity, instead the unique structure was embraced. As a result, a cascade reaction was uncovered whereby UV irradiation initiated a chemoselective C-C bond fragmentation (via intermediates 50 and 51) and removed the undesired chlorine atom and 9-BBN unit to give ambiguine H (12). This transformation illustrates an interesting case where a strategy is diverted through unanticipated reactivity, only to be restored by a subsequent chemoselective reaction.

Scheme 5.

A peculiar fifth ring (49) is found to undergo Norrish fragmentation, delivering the sterically crowded indole alkaloid, ambiguine H (12), which was synthesized without recourse to protecting groups.

These syntheses are also notable for both their brevity and complete avoidance of protecting group chemistry. This is a direct result of the decision to explore unknown chemistry in order to make the most direct retrosynthetic disconnection and the use of highly chemoselective reactions to differentiate similarly reactive functionality. Other approaches relying on previously proven methods would likely have been possible, however they almost certainly would have required significantly longer routes and the use of multiple protecting groups. In addition, gram quantities of many of these alkaloids are now readily available.

Stephacidins, Avrainvillamide, and Bursehernin

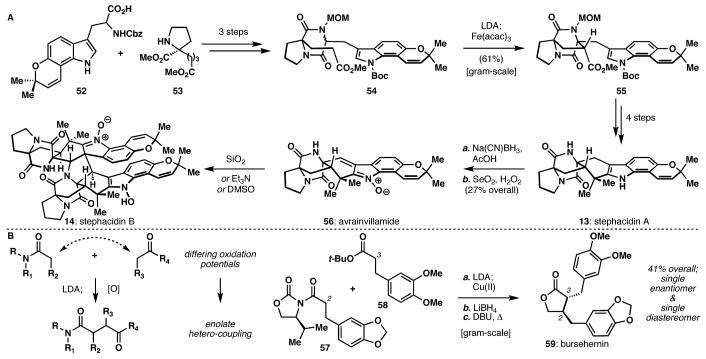

The structural complexity of known marine alkaloids took an astonishing leap forward in 2002 with the isolation of stephacidin B (14, Scheme 6A) a dimeric, prenylated tryptophan-proline metabolite isolated by scientists at Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS),19 and a clear relative of avrainvillamide (56), isolated independently by both the Fenical research group and Pfizer.20 Stephacidin A (13), also isolated by BMS, presented itself as an ideal initial target; its role as a biosynthetic precursor to 56 and 14 seemed probable, and its structure provided ample opportunity for invention-oriented synthesis design.21

Scheme 6.

Intra- and intermolecular enolate heterocoupling in total synthesis: The stephacidin alkaloids and bursehernin.

Central to our synthesis planning was the idea that two different enolates might undergo oxidative hetero-coupling both stereo- and chemoselectively, (54→55) and this coupling might be predictable based on enolate oxidation potentials and well-defined transition state geometries. In fact, subsequent to the stephacidin synthesis, these features were indeed fully explored in an intermolecular sense (Scheme 6B), ultimately resulting in an enantioselective synthesis of the unsymmetric lignan bursehernin (59).15

For the synthesis of 13, 14, and 56, the amino acid derivatives 52 and 53 were first subjected to peptide coupling and elaborated to diketopiperazine 54. Then, in a noteworthy example of the power of enolate heterocoupling, the ester and amide enolates derived from 54 coupled stereo- and chemoselectively to yield the characteristic bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane 55 embedded in the stephacidins. While this intermediate could be converted in short fashion to stephacidin A (13), oxidation to the unique α,β-unsaturated benzonitrone avrainvillamide (56) proved more difficult. Eventually, it was found that initial Gribble reduction of 13 was necessary for generation of the correct oxidation state (56), which could be achieved with selenium dioxide and hydrogen peroxide. Quite unexpectedly, dimerization occurred spontaneously, but reversibly, under a variety of passive conditions, producing stephacidin B (14) as the unnatural enantiomer.

Chartelline Alkaloids

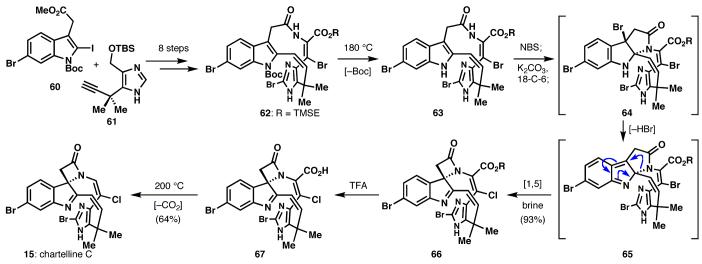

Investigations into the chartelline alkaloids,22 the first reported members of the “halohistophan”23 family, precipitated two different, but related, inquiries. First, we sought to approach the syntheses of these compounds as sheer chemical challenges, and to do so with the brevity implied by the guidelines in the introduction. This was a sizable task, as several approaches to the alkaloids had previously been described: although elegant and concise, these efforts nevertheless fell short of their targets.24 Second, we hoped to learn something of the innate chemical properties of the chartelline skeleton: how it behaved and what implications this behavior might hold for a biosynthetic hypothesis we had formulated, recognizing the securines as putative biosynthetic precursors to the chartellines via oxidative ring contraction.25

These two goals exhibited a synergistic effect on one another. Ultimately, an efficient synthesis of the general `halohistophan' macrocycle (60+61→62, Scheme 7) enabled inquiry into the properties of this structure, confirming its ability to serve as a viable precursor to the chartelline skeleton. Reciprocally, application of this newly discovered and potentially biomimetic reactivity (63→64→65) enabled an efficient synthesis of the natural product core containing the chartellines' hallmark β-lactam (66).26 The intermediacy of dearomatized pyrrolo-2H-indole 65 was implicated in the key transformation; this high-energy intermediate likely provides the driving force for forming various strained ring systems.18

Scheme 7.

Inquiry into a revised chartelline biosynthesis leads to the discovery of a remarkable [1,5]-sigmatropic rearrangement (65→66) and an unusual, non-catalyzed decarboxylation (67→15)

Two further reactions are worth comment. First, the facile bromine→chlorine exchange (65→66) that took place underscores the role of bromonium in the halohistophans' biosyntheses, while chlorine is likely incorporated exclusively solely as its anion.27 The in vitro halide metathesis exemplifies a chemoselective mimicry of nature, which is simply a consequence of the innate reactivity of the carbon scaffold. Second, and quite unexpectedly, a reagent-free thermal decarboxylation (67→15) was uncovered as a feasible means to chemoselectively excise the superfluous alkenylcarboxylate functionality, delivering the natural product, chartelline C, as a racemate.

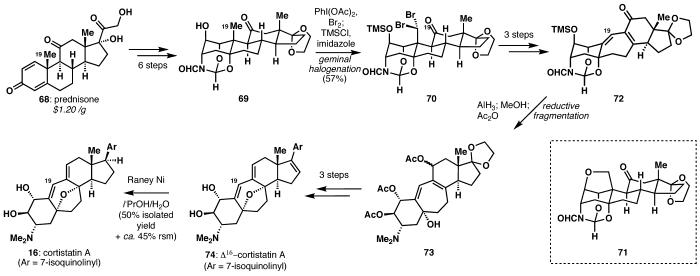

Cortistatins

Cortistatin A (16)28 represented an excellent opportunity to develop new chemoselective reactions. A semi-synthetic route to these marine steroids was deemed an acceptable strategy due to the economy of using prednisone-which is synthesized annually on multi-ton scale-as well as the dominance of semi-synthetic steroids on the rigorous U.S. pharmaceuticals market, constituting 10% of the top 200 brand name drugs. The most significant innovation in our synthesis occurred as a result of difficulties encountered during attempted oxidation of the angular C19 methyl group. Instructive failures guided the evolution of a synthesis strategy, finally resulting in the first alcohol-directed, hydrocarbon geminal dihalogenation (69→70), which established the correct methine oxidation state of the skeletal 19-carbon. The reaction proceeds by the standard mechanism for hypohalite radical halogenation,29 but in an iterative sense, wherein etherification (to 71) is suppressed by low temperatures. Interestingly, the selectivity for dibromination (57%) over mono- or tribromination well surpasses what would be expected with only the governance of statistics (a maximum yield of 27%).30

Elaboration of intermediate 70 to the unsaturated cycloheptyl ketone 72 allowed for the reductive fragmentation of an aza-dioxa-heteroadamantane (72→73), which was demonstrated to provide access to the fully functionalized A-ring of cortistatin A. While borane had performed admirably on a model system bearing no alkenes, the significantly less carbophilic aluminum reagent, alane, allowed for this highly chemoselective transformation to be performed in the presence of the crucial diene moiety.

Finally, just as the synthesis axinellamines A and B demonstrated the value of a strategic late-stage chemoselective oxidation, cortistatin necessitated a late-stage differentiating reduction event in the presence of several reductively labile functional groups. Nevertheless, as a result of this high-risk strategy, amine 74 could be elaborated to the natural product (16) in short order, largely owing to a chemoselective, Raney nickel-mediated hydrogenation of the 16,17-olefin (74→16) in preference to reduction of the diene, deoxygenation of the alcohols, or partial reduction of the isoquinoline.31,32

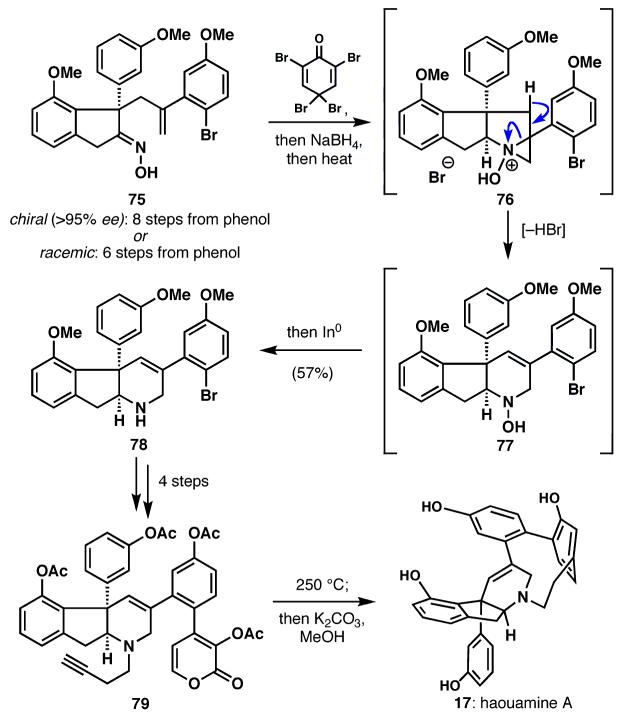

Haouamine A

Haouamine A (17), an unusual tunicate metabolite isolated from Aplidium haouarianum,33 stimulated a spate of activity among chemists shortly after its isolation in 2003.34 This widespread interest was prompted by a variety of challenges, including 1) synthesis of the unique indeno-tetrahydropyridine core; 2) synthesis of a remarkable `bent' aromatic ring embedded in a biarylparacyclophane; 3) control of potential atropisomerism35 around this unusual biphenyl linkage; and 4) inquiry into the biosynthetic origins of this structurally unprecedented alkaloid.36

Oxime 75, which contains the key chiral quaternary carbon of the haouamine skeleton, was synthesized in a short fashion either racemically35 or enantioselectively36 (6 vs. 8 steps, respectively). This intermediate could be converted to the haouamine core 78 in a one-pot cascade sequence, including position-selective aziridinium fragmentation (76→77) followed by chemoselective reduction (77→78). Further elaboration provided tetraacetate 79, whose alkyne and pyrone subunits reacted upon heating, extruding carbon dioxide to form haouamine tetraacetate, which could be solvolyzed to give the natural product (17). Notably, this macrocyclization proceeded with high atropselectivity to deliver the desired isomer in a 10:1 ratio to the undesired isomer.35 While investigating the tetrahydropyridine core, evidence was accumulated against a Chichibaban-like phenylacetaldehyde tetramerization as a likely biosynthetic pathway to these compounds.36,37 Instead, the absolute stereochemistry of haouamine A, which was determined by these studies, implicated a natural amino acid to be a metabolic precursor to the haouamines.

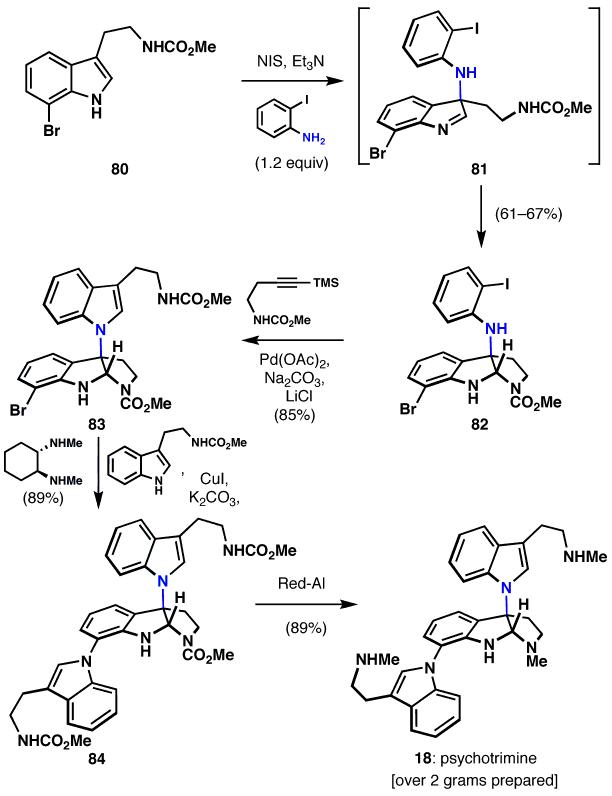

Psychotrimine

Psychotrimine (18)38 represents a nearly unassailable class of N1-C3 indole dimers whose syntheses had evaded chemists for decades.39 Constitutionally isomeric C3-C3 (indole numbering system) dimers have seen extensive investigation,40 reflecting the inherent preference for oxidative indole or tryptamine dimerization to favor C-C bond construction.41 Not surprisingly then, the structural novelty imposed by a C3-N1 linkage propelled the invention of a powerfully simple chemoselective method for C-N bond construction, specifically the formation of an indole C-3 quaternary linkage to an aniline nitrogen.42 The sequence that results from this simplifying transformation minimizes oxidation state fluctuations, functional group interconversions, and protecting group chemistry-which are all otherwise aspects of an inability to control chemoselectivity-thus streamlining the total synthesis of 18 to a mere four steps (from 80, which is readily available in one step from commercial material).

The route began with tryptamine 80, which when treated with 2-iodoaniline and N-iodosuccinimide, underwent smooth oxidative C-N bond formation, initially forming 81, the chain-tautomer of pyrroloindoline 82. The reaction appears to proceed via the intermediacy of an initial N-iodo aniline, which is intercepted by the electron rich indole, though more detailed mechanistic studies are necessary. Larock indole synthesis (82→83) provided the N1-C3 dimeric indole core, which could be subjected to a remarkably chemoselective Buchwald-Goldberg-Ullmann coupling to furnish the trimeric psychotrimine skeleton 84. Indeed, despite the presense of no less than 4 N-H bonds with somewhat similar pKa, only the desired N-C bond was formed in 89% isolated yield. Interestingly, palladisum-mediated N-C bond formation was completely non-selective in this coupling. Conversion of the carbamate groups to methyl groups using Red-Al produced the natural product (18) in an overall yield of 41-45% in four steps. It is noteworthy that to date over two grams of this natural product have been synthesized.

Conclusion and Outlook

Nature's cache of medicinally relevant or structurally captivating molecules is tremendous, and has propelled chemical knowledge a vast distance, even in the last decade. While this propulsion is fueled by Nature's persistent ability to surprise and amaze, the spark that ignites innovation can only be provided by human ingenuity in the face of opposition. In total synthesis endeavors, that opposition almost always manifests itself as a problem of chemoselectivity. The brilliant insights penned down by Trost over 25 years ago still ring true today:3 “Considering that lack of chemoselectivity frequently accounts for as many as 40 percent of the steps of a complex synthesis, much remains to be done for enahanced synthetic efficiency”. The introduction to this Account detailed a conceptual framework through which our lab approaches new undertakings. However, it cannot be overemphasized that the greatest challenges in synthesis are most often the least expected, and therefore also the most fruitful, since they provoke the chemist into dramatic action. In such circumstances, one should not bemoan the inability of existing chemistry to accomplish a desired transformation, but rather rejoice at opportunity to discover its answer! Ultimately, the only real failure is recourse to tried and true methods. The selectivity challenges encountered and finally overcome in total synthesis open a window into the future: while simply reading the literature demonstrates how far we've come, it is only repeated defeat and frustration that reveals how far we still have to go.

Scheme 2.

Enantioselective access to sceptrin and ageliferin.

Scheme 8.

The discovery of an alcohol-directed gem-dihalogenation, strategic masking of functionality in a unique orthoamide steroid skeleton, and late-stage chemoselective reduction enable the synthesis of cortistatin A (16)

Scheme 9.

A unique cascade sequence for forming the heterocyclic core and a pyrone Diels-Alder macrocyclization lead to a short synthesis of haouamine A (17)

Scheme 10.

A new method for oxidative C-N bond formation between indoles and anilines (80→82) enables a 4-step synthesis of psychotrimine (18).

Acknowledgment

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, The Scripps Research Institute, Amgen, AstraZeneca, the Beckman Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, DuPont, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, the Searle Scholarship Fund, and the Sloan Foundation.

Biographies

Biographical sketches

Ryan A. Shenvi received his B.S. degree in chemistry from Penn State University, performing research in the laboratories of Professors John R. Desjarlais and Raymond L. Funk. His doctoral research was conducted under the guidance of Professor Phil S. Baran at the Scripps Research Institute, from which he earned a Ph.D. in 2008. He is currently an NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein postdoctoral fellow in the laboratories of Professor E. J. Corey at Harvard University.

Daniel P. O'Malley received a B.S. degree in Chemistry from Rice University in 2003. He completed his Ph.D. in 2008 under the guidance of Professor Phil S. Baran at the Scripps Research Institute. He is presently an Alexander von Humboldt postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Professor Alois Fürstner at the Max Planck Institut für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany.

Phil S. Baran was born in New Jersey in 1977 and received his undergraduate education from NYU with Professor David I. Schuster in 1997. After earning his Ph.D. with Professor K. C. Nicolaou at Scripps in 2001 he pursued postdoctoral studies with Professor E. J. Corey at Harvard until 2003 at which point he began his independent career at Scripps, rising to the rank of Professor in 2008. His laboratory is dedicated to the study of fundamental organic chemistry through the auspices of natural product total synthesis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA. The Essence of Total Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:11929–11936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baran PS, Maimone TJ, Richter JM. Total Synthesis of Marine Natural Products Without Using Protecting Groups. Nature. 2007;446:404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature05569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The word “Chemoselectivity” and the challenges in designing reactions that are chemoselective were first pointed out by Trost in 1973, see Trost BM, Salzmann TN. New Synthetic Reactions. Sulfenylation-Dehydrosulfenylation as a Method for Introduction of Unsaturation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:6840–6842. For a detailed discussion, see Trost BM. Selectivity: A Key to Synthetic Efficiency. Science. 1983;219:245–250. doi: 10.1126/science.219.4582.245.

- 4.For a review on the isolation, biosynthesis, and synthetic studies of dimeric pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids, see Kock M, Grube A, Seiple I, Baran PS. The Pursuit of Palau'amine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6586–6594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701798. and references therein.

- 5.Baran PS, Li K, O'Malley DP, Mitsos C. Short, Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Sceptrin and Ageliferin by Programmed Oxaquadricyclane Fragmentation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:249–252. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northrop BH, O'Malley DP, Zografos AL, Baran PS, Houk KN. Mechanism of the Vinylcyclobutane Rearrangement of Sceptrin to Ageliferin and Nagelamide E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4126–4130. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Malley DP, Yamaguchi J, Young IS, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Total Synthesis of (±)-Axinellamines A and B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3637–3639. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi J, Seiple IB, Young IS, O'Malley DP, Maue M, Baran PS. Synthesis of 1,9-Dideoxy-pre-axinellamine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3634–3636. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su S, Seiple IB, Young IS, Baran PS. Total Syntheses of (±)-Massadine and Massadine Chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130 doi: 10.1021/ja8074852. doi: 10.1021/ja8074852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arndt H-D, Riedrich M. Synthesis of Marine Alkaloids from the Oroidin Family. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4785–4788. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore RE, Cheuk C, Yang X-QG, Patterson GML, Bonjouklian R, Smitka TA, Mynderse JS, Foster RS, Jones ND, Swartzendruber JK, Deeter JB. Hapalindoles, Antibacterial and Antimycotic Alkaloids from the Cyanophyte Hapalosiphon-Fontinalis. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:1036–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baran PS, Richter JM. Direct Coupling of Indoles with Carbonyl Compounds: Short, Enantioselective, Gram-Scale Synthetic Entry into the Hapalindole and Fischerindole Alkaloid Families. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7450–7451. doi: 10.1021/ja047874w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baran PS, Richter JM, Lin DW. Direct Coupling of Pyrroles with Carbonyl Compounds: Short, Enantioselective Synthesis of (S)-Ketorolac. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:609–612. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richter JM, Whitefield B,W, Maimone TJ, Lin DW, Castroviejo MP, Baran PS. Scope and Mechanism of Direct Indole and Pyrrole Couplings Adjacent to Carbonyl Compounds: Total Synthesis of Acremoauxin A and Oxazinin 3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12858–12869. doi: 10.1021/ja074392m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Baran PS, DeMartino MP. Intermolecular Oxidative Enolate Heterocoupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7083–7086. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DeMartino MP, Chen K, Baran PS. Intermolecular Enolate Heterocoupling: Scope, Mechanism, and Application. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11546–11560. doi: 10.1021/ja804159y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratmann K, Moore RE, Bonjouklian R, Deeter JB, Patterson GML, Shaffer S, Smith CD, Smitka TA. Welwitindolinones, Unusual Alkaloids from the Blue-Green-Algae Hapalosiphon-Welwitschii and Westiella-Intricata - Relationship to Fischerindoles and Hapalindoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9935–9942. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baran PS, Richter JM. Enantioselective Total Syntheses of Welwitindolinone A and Fischerindoles I and G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15394–15396. doi: 10.1021/ja056171r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richter JM, Ishihara Y, Masuda T, Whitefield BW, Llamas T, Pohjakallio A, Baran PS. Enantiospecific Total Synthesis of the Hapalindoles, Fischerindoles, and Welwitindolinones via a Redox Economic Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130 doi: 10.1021/ja806981k. doi: 10.1021/ja806981k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian-Cutrone J, Huang S, Shu Y-Z, Vyas D, Fairchild C, Menendez A, Krampitz K, Dalterio R, Klohr SE, Gao Q. Stephacidin A and B: Two Structurally Novel, Selective Inhibitors of the Testosterone-Dependent Prostate LNCaP Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14556–14557. doi: 10.1021/ja028538n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Fenical W, Jensen PR, Cheng XC. Avrainvillamide, a Cytotoxic Marine Natural Product, and Derivatives thereof. U.S. Patent. 2000 6,066,635.; (b) Sugie Y, Hirai H, Inagaki T, Ishiguro M, Kim Y-S, Kojima Y, Sakakibara T, Sakemi S, Sugiura A, Suzuki Y, Brennan L, Duignan J, Huang LH, Sutcliffe J, Kojima N. A New Antibiotic CJ-17,665 from Aspergillus ochraceus. J. Antibiot. 2001;54:911–916. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Baran PS, Guerrero CA, Ambhaikar NB, Hafensteiner BD. Short, Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Stephacidin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:606–609. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Baran PS, Guerrero CA, Hafensteiner BD, Ambhaikar NB. Total Synthesis of Avrainvillamide (CJ-17,665) and Stephacidin B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3892–3895. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Baran PS, Hafensteiner BD, Ambhaikar NB, Guerrero CA, Gallagher JD. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Avrainvillamide and the Stephacidins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8678–8693. doi: 10.1021/ja061660s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahback L, Christophersen C. Marine Alkaloids.19. Three New Alkaloids, Securamines E-G, from the Marine Bryozoan Securiflustra Securifrons. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:175–177. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Named for the presumed origins of the securamine/securamine, chartelline, and chartellamide alkaloids as all derived from halogenated histidine-tryptophan metabolites.

- 24.For studies towards the chartellines and related alkaloids, see refs 26,27, and Sun C, Lin X, Weinreb SM. Explorations on the Total Synthesis of the Unusual Marine Alkaloid Chartelline A. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:3159–3166. doi: 10.1021/jo060084f.Sun C, Camp JE, Weinreb SM. Construction of Beta-Haloenamides Via Direct Copper-Promoted Coupling of Lactams with 2-Chloro and 2-Bromo Vinyliodides. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1779–1781. doi: 10.1021/ol060093a.; Kajii S, Nishikawa T, Isobe M. Synthetic Studies and Biosynthetic Speculation on Marine Alkaloid Chartelline. Chem. Commun. 2008:3121–3123. doi: 10.1039/b803797c.

- 25.Baran PS, Shenvi RA, Mitsos CA. A Remarkable Ring Contraction En Route to the Chartelline Alkaloids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3714–3717. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baran PS, Shenvi RA. Total Synthesis of (±)-Chartelline C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14028–14029. doi: 10.1021/ja0659673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.For a more detailed discussion, see Shenvi RA. PhD Thesis. The Scripps Research Institute; 2008. For a contrary view, see Black PJ, Hecker EA, Magnus P. Magnus, P. Studies Towards the Synthesis of the Marine Alkaloid Chartelline C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:6364–6367. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.07.040.

- 28.Aoki S, Watanabe Y, Sanagawa M, Setiawan A, Kotoku N, Kobayashi M. Cortistatins A, B, C, and D, Anti-Angiogenic Steroidal Alkaloids, from the Marine Sponge Corticium Simplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3148–3149. doi: 10.1021/ja057404h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cekovic Z. Reactions of Delta-Carbon Radicals Generated by 1,5-Hydrogen Transfer to Alkoxyl Radicals. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:8073–8090. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McQuarrie DA, Simon JD. Physical Chemistry: A Molecular Approach. University Science Books; Sausolito, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shenvi RA, Guerrero CA, Shi J, Li C-C, Baran PS. Synthesis of (+)-Cortistatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:7241–7243. doi: 10.1021/ja8023466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.For two beautiful syntheses of cortistatin A from Hajos-Parrish ketone, see: Nicolaou KC, Sun Y-P, Peng X-S, Polet D, Chen DY-K. Total Synthesis of (+)-Cortistatin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47 doi: 10.1002/anie.200803550. EarlyView.; Lee HM, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Shair MD. Enantioselective Synthesis of (+)-Cortistatin A, a Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Endothelial Cell Proliferation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008130 doi: 10.1021/ja8071918. doi: 10.1021/ja8071918. For studies towards the cortistatins, see: Dai M, Danishefsky SJ. An Oxidative Dearomatization Cyclization Model for Cortistatin A. Heterocycles. 2008 doi: COM-08-S(F)6.Yamashita S, Iso K, Hirama M. A Concise Synthesis of the Pentacyclic Framework of Cortistatins. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3413–3415. doi: 10.1021/ol8012099.Simmons EM, Hardin AR, Guo X, Sarpong R. Rapid Construction of the Cortistatin Pentacyclic Core. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6650–6653. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802203.Craft DT, Gung BW. The First Transannular [4+3] cycloaddition reaction: Synthesis of the ABCD Ring Structure of Cortistatins. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:5931–5934. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.155.Dai M, Danishefsky SJ. A Concise Synthesis of the Cortistatin Core. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6610–6612. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.09.018.Dai M, Wang Z, Danishefsky SJ. A Novel α,β-Unsaturated Nitrone-Aryne [3+2] Cycloaddition and its Application in the Synthesis of the Cortistatin Core. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6613–6616. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.09.019.Kürti L, Czakó B, Corey EJ. A Short, Scalable Synthesis of the Carbocyclic Core of the Anti-Angiogenic Cortistatins from (+)-Estrone by B-Ring Expansion. Org. Lett. 2008;10:5247–5250. doi: 10.1021/ol802328n.

- 33.Garrido L, Zubía E, Ortega MJ, Salva J. Haouamines A and B: A New Class of Alkaloids from the Ascidian Aplidium Haouarianum. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:293–299. doi: 10.1021/jo020487p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Smith ND, Hayashida J, Rawal VH. Facile Synthesis of the Indeno-Tetrahydropyridine Core of Haouamine A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4309–4312. doi: 10.1021/ol0512740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Grundl MA, Trauner D. Synthetic Studies toward the Haouamines. Org. Lett. 2006;8:23–25. doi: 10.1021/ol052262h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wipf P, Furegati M. Synthesis of the 3-Aza-[7]-Paracyclophane Core of Haouamine A and B. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1901–1904. doi: 10.1021/ol060455e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jeong JH, Weinreb SM. Formal Total Synthesis of the Cytotoxic Marine Ascidian Alkaloid Haouamine A. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2309–2312. doi: 10.1021/ol060556c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fürstner A, Ackerstaff J. Formal Total Synthesis of (-)-Haouamine A. Chem. Commun. 2008:2870–2872. doi: 10.1039/b805295f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baran PS, Burns NZ. Total Synthesis of (±)-Haouamine A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3908–3909. doi: 10.1021/ja0602997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns NZ, Baran PS. On the Origin of the Haouamine Alkaloids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;47:205–208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gravel E, Poupon E, Hocquemiller R. Biogenetic Hypothesis and First Steps Towards a Biomimetic Synthesis of Haouamines. Chem. Commun. 2007:719–721. doi: 10.1039/b613737g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takayama H, Mori I, Kitajima M, Aimi N, Lajis NH. New Type of Pentameric Indole Alkaloids from Psychotria Rostrata. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2945–2948. doi: 10.1021/ol048971x. A synthesis of 16 was recently reported: Matsuda Y, Kitajima M, Takayama H. First Total Synthesis of Trimeric Indole Alkaloid Psychotrimine. Org. Lett. 2008;10:125–128. doi: 10.1021/ol702637r.

- 39.For the first report of an N1-C3 linked indole dimer natural product, see: McInnes AG, Taylor A, Walter JA. The structure of chetomin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:6741. doi: 10.1021/ja00437a074. For an alternative approach to N1-C3 bond formation, appearing subsequent to our own work, see: Espejo VR, Rainier JD. An expeditious synthesis of C(3)-N(1') heterodimeric indolines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12894–12895. doi: 10.1021/ja8061908.

- 40.Steven A, Overman LE. Total Synthesis of Complex Cyclotryptamine Alkaloids: Stereocontrolled Construction of Quaternary Carbon Stereocenters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5488–5508. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.For example, see: Ishikawa H, Takayama H, Aimi N. Dimerization of Indole Derivatives with Hypervalent Iodines(III): a New Entry for the Concise Total Synthesis of rac- and meso-Chimonanthines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5637–5639.

- 42.Newhouse TJ, Baran PS. Total Synthesis of (±)-Psychotrimine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10886–10887. doi: 10.1021/ja8042307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]