Summary

Positive control mutants defining 20 residues of the quorum-sensing activator TraR were isolated that bind DNA but show defects in activating transcription from Class I, Class II, or both types of promoters. These PC residues, located in both the N- and C-terminal regions, combine to form three patches, one on the top (II) and two near the DNA binding domain on both lateral faces of the dimer (I and III). Patches I and II, but not Patch III involve residues from both protomers and are essential for activation. TraR-mediated activation in E. coli requires expression of the α–subunit of Agrobacterium (αAt). We report that TraR also activates a Class II promoter in E. coli when co-expressed with σ70At. Analyses in E. coli expressing αAt, σ70At, or both subunits indicate that most of the PC residues are important for interactions with αAt and that these interactions are predominant for activation of Class II promoters. Using the E. coli system we identified nine residues in the C-terminal domain of αAt that are required for stimulating TraR-mediated activation. We conclude that N- and C-terminal residues of TraR from both protomers cooperate to define regions of the protein important for interactions with RNAP.

Keywords: Quorum-sensing, TraR, α-subunit, σ70-subunit, Transcriptional Activation, Agrobacterium tumefaciens

Introduction

TraR is a member of the LuxR family of quorum-sensing regulators and controls conjugative transfer and copy number of the Ti plasmid of the plant pathogen, Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Piper et al., 1993; Li and Farrand, 2000; Pappas and Winans, 2003). Most members of the LuxR family are transcriptional activators and require as ligands acyl homoserine lactone (acyl-HSL) signals to bind DNA and activate transcription (Miller and Bassler, 2001; Whitehead et al., 2001; Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002; Nasser and Reverchon, 2007). Upon binding N-3-(oxo-octanoyl)-L-HSL (3-oxo-C8-HSL), TraR forms active dimers and becomes more resistant to proteolysis (Zhang et al., 1993; Zhu and Winans, 1999; Qin et al., 2000; Pinto and Winans, 2009). Each protomer of the dimeric activator is composed of two functional domains joined by a 12-residue flexible linker (Vannini et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2003; White and Winans, 2007). The N-terminal 162-residue segment contains the acyl-HSL binding site and the primary dimerization domain while the C-terminal 60-residue segment contains secondary dimerization regions and a helix-turn-helix-type (HTH) DNA binding domain. Based on crystal structure of a TraR dimer from an octopine-type Ti plasmid bound to its DNA recognition element, both of the two C-terminal domains and the two N-terminal domains display an axis of two-fold symmetry. However, these two axes of symmetry are aligned at approximately a 90° angle to one another, leading to high asymmetry of the overall structure of this dimeric activator. As a result of this asymmetry, one protomer is compact while the other is somewhat extended (See Fig.1) (Zhang et al., 2002; Vannini et al., 2002).

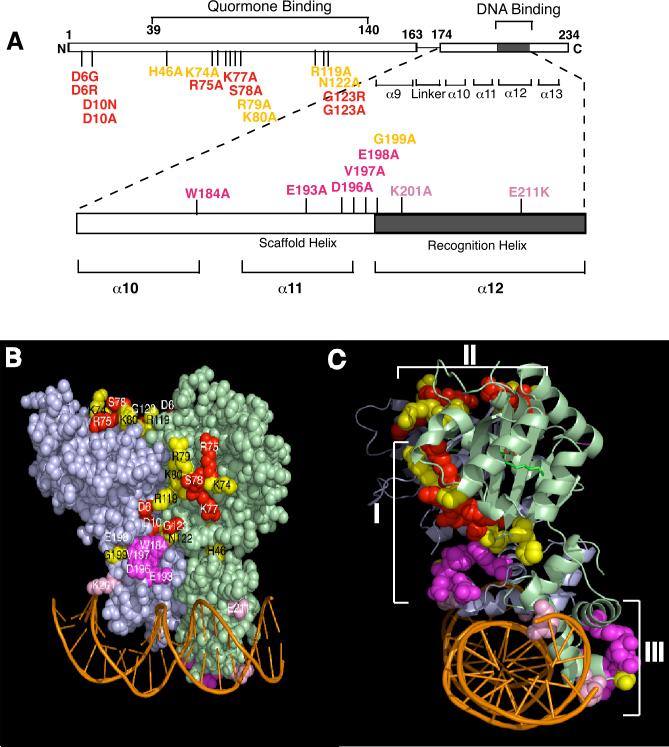

Figure 1. Locations of single amino acid substitutions on the structure of TraR that yield a PC phenotype.

A, A linear depiction of TraR with the locations of PC substitutions indicated. B and C, three distinct patches formed by PC residues on the TraR dimer structure complexed with an 18 bp tra box DNA fragment presented in two orthological views. Purple protomer: the compact monomer in which the N- and C-terminal domains contact each other; Green protomer: the extended monomer within which there is no contact between the N- and C-terminal domains. Residues in red and magenta indicate sites at which substitutions in the N- and C-regions of TraR respectively give positive control phenotypes on a Class II promoter. Residues in yellow or pink indicate sites at which substitutions show positive control phenotypes only on Class I but not on Class II or only on Class II but not on Class I promoters.

Activators such as CAP, BMRR, and CooA that bind to a two-fold symmetric DNA recognition element, function as two-fold symmetrical dimers (Busby and Ebright, 1997; 1999; Zheleznova-Heldwein and Brennan, 2001; Komori et. al., 2007). Among the most well-studied activators, dimeric CAP binds to DNA, recognizing a 22-bp inverted repeat consensus site, and in several cases it activates bi-directional promoters (Busby and Ebright, 1999; Benoff et al., 2002). CAP-dependent promoters can be classified into two groups depending upon the location of the DNA binding site. In Class I promoters, the activator binding site is centered approximately 65 bp upstream of the +1 site. At such promoters, CAP is believed to recruit RNAP by interacting specifically with the C-terminal domain of the α-subunit (Lawson et al., 2004). In Class II promoters, the DNA binding site is centered adjacent to the –35 promoter element, and makes multiple contacts with RNAP including those with α and σ70 subunits (Niu et al., 1996; Rhodius et al., 1997; Busby and Ebright, 1997; 1999). TraR also activates from binding sites, called the tra box, showing two-fold symmetry. Based on the location of this 18-bp inverted repeat, five of the seven known TraR-dependent promoters, including PtraAFBH, PtraCDG, PtraItrb and PrepA1 and PrepA3 are Class II-type in nature (Farrand et al., 1996; Fuqua and Winans, 1996; Li and Farrand, 2000; Pappas and Winans, 2003), while two, PtraM and PrepA2 are Class I-type promoters (Hwang et al., 1995; Fuqua et al., 1995; White and Winans, 2005). Moreover, two of these Class II promoters, PtraAFBH and PtraCDG are divergently oriented and are activated by TraR bound to a single, centrally located tra box (Farrand et al., 1996; Fuqua and Winans, 1996). Given its asymmetry, however, it is very likely that TraR behaves differently with respect to its interaction with RNAP as compared to highly symmetric dimeric activators like CAP. As such, studies of the interactions between TraR and RNA polymerase could serve as a prototype to understand the mechanisms by which this large family of LuxR-type AHL-dependent quorum-sensing activators interacts with and recruits RNAP to their promoters.

Our previous studies of the closely related TraR from the nopaline-type Ti plasmid pTiC58 showed that alterations at two N-terminal residues, Asp-10 and Gly-123, yield a strong positive control (PC) phenotype; both mutant proteins retain wild-type levels of DNA binding activity but fail to activate transcription (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Qin et al., 2004a). When co-expressed with the wild-type protein, these mutants exhibit dominant negativity; they strongly inhibit activation of the reporter by wild-type TraR (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Qin et al., 2004a). However, when co-expressed as pairs, TraRD10A and TraRG123A, or TraRD10A and TraRG123R complemented one another. Together, these results suggest that the regions of the two protomers defined by these two residues interact with each other in the dimer (Qin et al., 2004a). Consistent with this hypothesis, Asp-10 of one protomer and Gly-123 of the other lie adjacent to each other in the active dimers and could contribute to an activating surface patch. In addition, because of its asymmetry, the two patches are located on different surfaces of the dimer: one patch lies on the lateral face of dimer close to the bound DNA, while the other is located on the top face of the dimer (Fig.1B, 1C) (Zhang et al., 2002; Vannini et al., 2002).

Several lines of genetic evidence suggest that LuxR is an ambidextrous activator, and as such makes contacts with the α- and σ70- subunits of RNAP (Stevens et al., 1994; 1999; Finney et al., 2002; Trott and Stevens, 2001; Johnson et al., 2003). Given the overall relatedness of TraR and LuxR and the location of the tra box within target promoters, TraR also is likely to be an ambidextrous activator, interacting with the α-subunit and with σ70 of RNAP during initiation of transcription from Class II promoters. In this regard, two lines of evidence indicate that TraR directly interacts with the α-subunit of RNAP. First, TraR requires co-expression of the α-subunit from A. tumefaciens (αAt) to activate transcription from a Class II promoter in E. coli (Qin et al., 2004a). Second, as assessed by in vitro assays, TraR directly interacts with the C-terminal domain of the α-subunit (αCTD) from A. tumefaciens, and this interaction is dependent upon Asp-10 and Gly-123; substitution mutations at one or the other of these residues of the activator abolish α-subunit binding (Qin et al., 2004a).

In this study, we identified and characterized a series of N- and C-terminal PC mutants of TraR from pTiC58. We also expanded our E. coli system (Qin et al., 2004A) to measure the influence of σ70At on activation by TraR in this enteric host. Using these tools we found that maximum expression from a Class II promoter is dependent upon coexpressing both α and σ70 subunits from Agrobacterium. Moreover, using this system coupled with assays using a TraR-dependent Class I promoter reporter, we distinguished between PC residues of TraR required for interaction with α and those influencing interaction with σ70. Finally, we identified residues in the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the α-subunit from A. tumefaciens that are required for TraR-mediated activation.

Results

Identification of N-terminal mutations with a positive control phenotype

In our previous studies we identified four PC mutants of TraR from the nopaline-type Ti plasmid pTiC58 located at Asp-10 and Gly-123: D10N, D10A, G123R and G123A (Luo and Farrand, 1999; Qin et al., 2004a). These mutant proteins still bind tra box DNA as well as the wild-type protein, but fail to activate transcription. Since the glycine at position 123 does not have a side group, we made alanine substitutions at positions Asn-122 and Ser-124 to test if residues around Gly-123 could play any role in activation. As shown in Table 1, Asn122→Ala did not significantly affect the activation activity from our Class II reporter while Ser124→Ala completely lost both activation and DNA binding activity, suggesting a structural role for Ser-124 and Gly-123.

Table 1.

In vivo activation and repression activities and in vitro DNA binding affinities of TraR N-terminal mutantsa

| traR allele | Activationb |

Repressionc |

Ratiod | DNA Bindinge | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activityf | %activationg | Activityf | %inhibitionh | |||

| None | 2 | 0 | 208 | 0 | NAi | NA |

| Wild-type | 704 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 1 | 8×10−9 |

| D6G | 13 | 1.5 | 7 | 100 | 67 | 8×10−9 |

| D6R | 12 | 1.4 | 8 | 100 | 71 | 4×10−9 |

| D10A | 2 | 0 | 12 | 98 | >100 | 8×10−9 |

| R45A | 669 | 95 | 8 | 100 | 1.1 | NTj |

| H46A | 521 | 74 | 43 | 82 | 1.1 | NT |

| K74A | 706 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 1 | NT |

| R75A | 542 | 77 | 8 | 100 | 1.3 | NT |

| K77A | 317 | 45 | 9 | 99 | 2.2 | NT |

| S78A | 415 | 59 | 8 | 100 | 1.7 | NT |

| R79A | 669 | 95 | 8 | 100 | 1.1 | NT |

| K80A | 703 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 1 | NT |

| R119A | 591 | 84 | 8 | 100 | 1.2 | NT |

| N122A | 598 | 85 | 30 | 89 | 1 | NT |

| G123A | 11 | 1 | 7 | 100 | 100 | 8×10−9 |

| S124A | 2 | 0 | 220 | 0 | NA | NT |

Mutants with PC properties are indicated by bold font.

In vivo activation by TraR and its mutant alleles was assessed in A. tumefaciens NTL4 harboring the reporter plasmid pH4I41 and the pZLQ derivative expressing the indicated traR gene.

In vivo repression by TraR and its mutant alleles was assessed in E.coli DH5α harboring the reporter plasmid pPB1 and the pZLQ derivative expressing the indicated traR gene.

Repression/activation ratio was calculated as the fold repression value divided by the fold activation value.

DNA binding affinity of TraR and its mutant alleles was assessed by gel shift assays as described in Experimental procedures. The binding constant is expressed as the concentration of TraR (M) protein that resulted in 50% binding of the total probe DNA (7.5×10−10M).

Expressed as units of β-galactosidase activity /109 cfu as described in Experimental procedures. Each allele of traR was tested a minimum of three times, and the results shown are from a representative experiment.

%activation is calculated as {(mutant-none)/(wt-none)}×100, where mutant, none and wt are β-galactosidase activities of strains expressing mutant TraR, no TraR and wild-type TraR respectively.

%repression is calculated as {( none-mutant)/(none-wt)}×100, where mutant, none and wt are β-galactosidase activities of strains expressing mutant TraR, no TraR and wild-type TraR respectively.

NA=Not Applicable.

NT=Not Tested

We then employed random error-prone PCR mutagenesis to identify additional PC mutants. In this screen we isolated two mutants, D6G and D6R, each of which retained full DNA binding activity as measured by both repressor activity and gel retardation assays but lost over 98% of their activation activity (Table 1). The Asp-6 residue is surface-exposed, lies close to Asp-10, and these two residues in one protomer combine with Gly-123 from the other protomer to form the two D6-D10/G123 patches in the TraR dimer (Fig. 1B, 1C).

To further explore the region, we converted to alanines the surface-exposed residues near the two D6-D10/G123 patches in the N-terminal segment of the dimer. Of the nine alanine substitution mutants, at positions 45, 46, 74, 75, 77, 78, 79, 80 and 119, all retained more than 80% DNA binding activity as assessed by our repression assay and all but four activated transcription at levels of 80% or greater (Table 1). The four activation-defective mutants, H46A, R75A, K77A and S78A, showed activities ranging from 45 to 77% that of wild-type TraR. Setting as a cutoff a loss of 20% or greater in activation activity (Niu et al., 1993), we retained these four N-terminal mutants as candidate PC alleles (Fig.1 and Table 1). As assayed by Western analysis, all of these mutant proteins were detectable in cells at levels indistinguishable from wild-type TraR (data not shown).

Identification of C-terminal mutations with a positive control phenotype

Considering that the α and σ70 subunits bind at or near promoters and often contact activators around the DNA-binding domain, we used three strategies to screen for PC mutants of TraR with alterations in the C-terminal DNA interaction region. In the first, reasoning that residues involved in contacting components of RNAP would be conserved among orthologs of traR from plasmids in related α-proteobacteria such as A. rhizogenes (Moriguchi et al., 2001), Sinorhizobium meliloti (Marketon and Gonzalez, 2002) and Rhizobium spp (Danino et al., 2003; He et al., 2003; Tun-Garrido et al., 2003), we mutagenized the 14 C-terminal residues that are conserved in all of the TraR proteins known to be functional. In the second, in screens for mutants of TraR that do not interact with TraM, we had isolated three mutants with single amino acid substitutions in the C-terminal region (Luo et al., 2000; Qin et al., 2004b; Qin et al., 2007). In the third approach, we mutagenized to alanines C-terminal residues of TraR that correspond to residues identified as exhibiting PC properties in LuxR (Egland and Greenberg, 2001) and in TraR from octopine-type Ti plasmids (White and Winans, 2005).

Of the total of 20 new C-terminal mutants, four of them, M189A, E192A, S204A and A212V retained more than 85% activity in both repression and activation assays. Six of the remaining 16 mutants, L174A, G188A, T190I, A195V, V205A and R215A, exhibited less than 15% activity in activation and repression assays, whereas two mutants (G199A, V200A) were almost equally affected in repression and activation. The Leu-209→Ala substitution lost virtually all activator function, and 70% of its repression activity. Leu-209 is located between two adjacent residues in the recognition helix that make specific contacts with tra box nucleotides (Vannini et al., 2002; White and Winans, 2007; Zhang et al., 2002), suggesting that the L209A mutation affects DNA binding rather than activation per se. The remaining seven mutants (W184A, E193A, D196A, V197A, E198A, K201A, and E211K) are more defective in activation than in repression, and thus were retained as PC mutants (colored in magenta in Fig.1 and highlighted in bold in Table 2).

Table 2.

In vivo activation and repression activities and in vitro DNA binding affinities of TraR C-terminal mutantsa

| traR allele | Activationb |

Repressionc |

Ratiod | DNA Bindinge | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activityf | %Activationg | Activityf | %Inhibitionh | |||

| None | 2 | 0 | 208 | 0 | NAi | NA |

| Wild-type | 704 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 1 | 8×10−9 |

| L174A | 6 | 0.6 | 213 | 0 | 0 | NTj |

| W184A | 108 | 15 | 116 | 46 | 3 | 8×10−8 |

| G188A | 2 | 0 | 243 | 0 | NA | NT |

| M189A | 626 | 89 | 38 | 85 | 0.9 | NT |

| T190I | 92 | 13 | 199 | 4 | 0.3 | NT |

| E192A | 701 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 1 | NT |

| E193A | 380 | 42 | 38 | 85 | 2 | 8×10−8 |

| A195V | 3 | 0.1 | 216 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| D196A | 4 | 0.3 | 97 | 55 | >100 | 2×10−9 |

| V197A | 263 | 37 | 22 | 93 | 2.5 | 1.7×10−8 |

| E198A | 4 | 0.3 | 106 | 51 | >100 | NT |

| G199A | 391 | 55 | 124 | 42 | 0.8 | NT |

| V200A | 318 | 45 | 110 | 49 | 1.1 | 4×10−8 |

| K201A | 441 | 63 | 10 | 99 | 1.6 | 2.5×10−7 |

| S204A | 705 | 100 | 8 | 99 | 1 | NT |

| V205A | 18 | 2 | 199 | 4 | 2 | NT |

| L209A | 10 | 1 | 145 | 31 | 31 | NT |

| E211K | 416 | 59 | 13 | 97 | 1.6 | NT |

| A212V | 697 | 99 | 9 | 99 | 1 | NT |

| R215A | 81 | 11 | 196 | 6 | 0.5 | NT |

Assays and other information are as described in footnotes to Table 1.

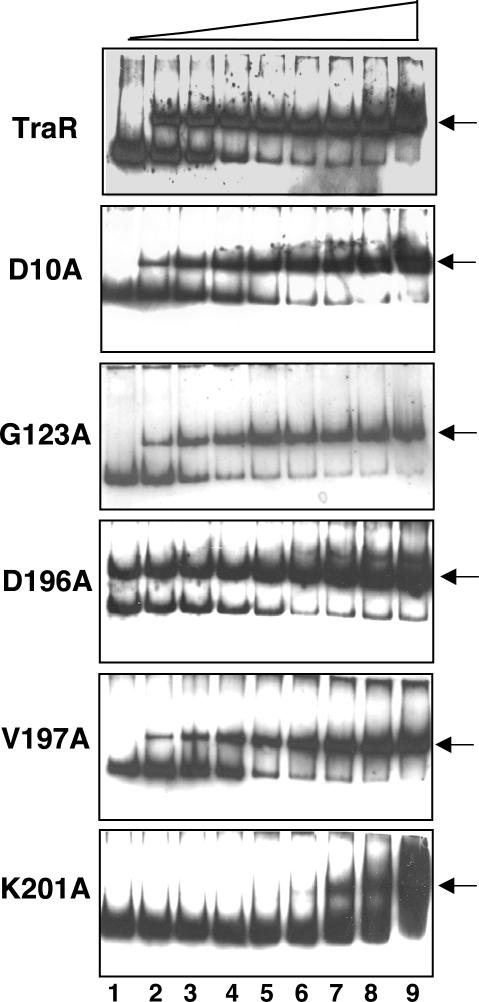

In addition to the in vivo repression assay, we quantified the DNA binding properties of each of the PC mutants using gel retardation assays. All but two of these mutants displayed similar relative binding affinities in these two assays (Table 1, Table 2, and Fig.2). TraR D196A lost about 45% repression activity in vivo but displayed levels of affinity for the tra box similar to that of the wild-type protein in vitro, while TraR K201A acted in an opposite fashion; this mutant showed near-wild type repression activity in vivo but over a hundred-fold reduced binding affinity in vitro (Table 2, Fig.2), suggesting that some factors in vivo may modulate the interactions between TraR and tra box DNA. All of these mutant proteins were produced in soluble form in cells grown with 3-oxo-C8-HSL and are detectable in cells at amounts equivalent to that of the wild-type protein independently expressed from the same vector (Qin et al., 2007; data not shown).

Figure 2. DNA binding affinities of TraR mutants as determined by gel mobility shift assays.

Mobility shift assays of wild-type TraR and representative PC mutants were conducted as described in Experimental procedures, TraR DNA-binding constants were defined by the concentrations of TraR at which 50% of the total probe (7.5×10−10 M) was shifted as a TraR-DNA complex (indicated by arrows). TraR and its representative mutants were tested at concentrations of 0 (2 nM for D196A), 4, 8, 17, 34, 67, 125, 250 and 500 nM, loaded in lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 6, 7, 8, and 9, respectively.

Relative activation activities of TraR mutants at Class I and Class II promoters

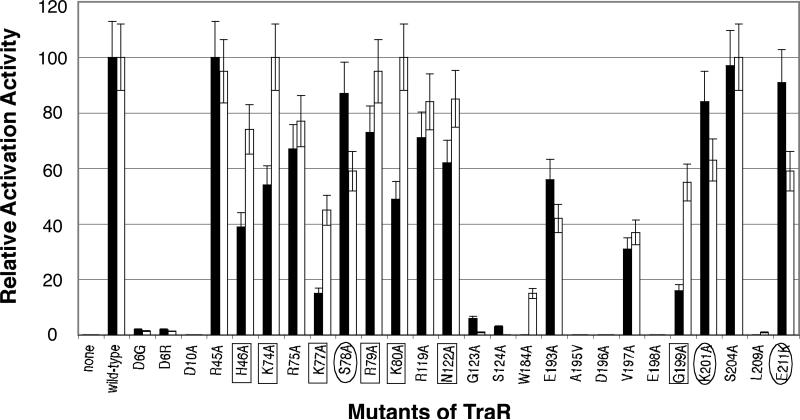

To differentiate residues involved in interacting with the α-subunit from those that interact with σ70, we compared the activation properties of all of the TraR mutants on Class I and Class II promoter reporters. We reasoned that PC mutants showing a reduced activity on both promoters or only on the Class I promoter would represent proteins affected in interactions with the α-subunit, while those showing a reduced activity on Class II but not on Class I promoters, would correspond to activators defective in interaction with σ70 or with αNTD but not with αCTD (William et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 1994; Niu et al., 1996; Lawson et al., 2004).

Of the 26 mutants tested, 16 including D6G(R), D10A, R45A, R75A, R119A, G123A, S124A, W184A, E193A, A195V, D196A, V197A, E198A, S204A and L209A exhibited similar activation properties on Class I and Class II promoters (Fig. 3 and Table S1). Ten mutants displayed differences of more than 20% in relative activation on the two types promoters. Seven of these, including H46A, K74A, K77A, R79A, K80A, N122A and G199A, showed levels of activity at least 20% higher on Class II as compared to Class I promoters while the other three, S78A, K201A, and E211K, displayed levels of activity at least 20% higher on Class I as compared to Class II promoters (Fig. 3 and Table S1).

Figure 3. Influence of single amino acid substitutions in TraR on activation of Class I and Class II promoters in A. tumefaciens.

Wild-type TraR and a series of single amino acid substitution mutants were tested for activation of the traM::lacZ Class I reporter (closed bars) and the traCDG::lacZ Class II reporter (open bars) in A. tumefaciens as described in Experimental procedures. In all cases the cultures were supplemented with N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-HSL at a final concentration of 50 nM. Alleles in boxes represent mutations that disproportionately affect activation at the Class I promoter while alleles in ovals represent mutations that have the greatest effect on activation at the Class II promoter. The data represent the averages of three repetitions and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Five N-terminal mutants, K74A, R79A, K80A, R119A and N122A, while still active on the Class II promoter reporter, showed losses in activation 46%, 27%, 51%, 29% and 38% respectively on the Class I promoter (Fig. 3 and Table S1). In addition, the H46A, K77A and G199A mutants, while showing 26%, 55% and 45% loss of activation activity on the Class II promoter respectively, exhibited between 61 and 85% decrease of activity on the Class I promoter (Fig. 3 and Table S1). These results suggest that these residues play only a modest role in activation from a Class II promoter but may contribute to interactions with RNAP specific to activation from a Class I promoter. Based on this observation we call these eight mutants, H46A, K74A, K77A, R79A, K80A, R119A, N122A and G199A, Class I-specific PC mutants (Fig.1 and Fig. 3). On the other hand, the three mutants S78A, K201A and E211A are more active on Class I than Class II promoters (Fig. 3) and therefore are Class II-specific PC mutants.

PC residues located in the N-terminal but not the C-terminal half display dominant negativity

Assessing dominant negativity allows us to identify residues required in both protomers as compared to those required in only one protomer of the TraR dimer (Luo et al., 2003; Qin, et al., 2004a). We co-expressed each new mutant identified in this study with wild-type TraR to examine its dominance properties.

On the Class II promoter, all of the C-terminal PC mutants including W184A, E193A, D196A, V197A, E198A, K201A and E211K were recessive, while among the N-terminal mutants, all but R75A and S78A, exhibited significant dominant negativity (Table 3). As expected, co-expressing the C-terminal DNA binding-defective mutants L174A, G188A, and A195V, resulted in moderate inhibition of wild-type TraR activity. The four other null mutants, T190I, V205A, L209A, and R215A, were recessive to wild-type TraR (Table 3).

Table 3.

Dominant negativity of TraR mutants.

| TraR allelea | Dominant negativity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class II promoterb |

Class I promoterc |

|||

| Activityd | % Inhibitione | Activityd | % Inhibitione | |

| None | 156 | 0 | 201 | 0 |

| Wild type | 262 | (68)f | 241 | (20) |

| D6G | 61 | 61 | 34 | 83 |

| D6R | 61 | 61 | 86 | 57 |

| D10A | 3 | 98 | 86 | 57 |

| R45A | 179 | (15) | 175 | 13 |

| H46A | 204 | (31) | 149 | 26 |

| R74A | 187 | (20) | 125 | 38 |

| R75A | 172 | (10) | 143 | 29 |

| K77A | 92 | 41 | 127 | 37 |

| S78A | 142 | 9 | 143 | 29 |

| R79A | 187 | (20) | 129 | 36 |

| K80A | 165 | (6) | 129 | 36 |

| R119A | 134 | 14 | 187 | 7 |

| N122A | 162 | (4) | 133 | 34 |

| G123A | 5 | 97 | 82 | 59 |

| S124A | 125 | 20 | 165 | 18 |

| L174A | 117 | 25 | NTg | |

| W184A | 167 | (7) | 191 | 5 |

| G188A | 100 | 36 | NT | |

| M189A | 268 | (72) | NT | |

| T190I | 139 | 11 | NT | |

| E192A | 248 | (59) | NT | |

| E193A | 206 | (32) | 207 | (3) |

| A195V | 87 | 44 | 165 | 18 |

| D196A | 154 | 1 | 191 | 5 |

| V197A | 209 | (34) | 245 | (22) |

| E198A | 145 | 7 | 235 | (17) |

| G199A | 184 | (18) | 223 | (11) |

| V200A | 246 | (58) | NT | |

| K201A | 248 | (59) | 253 | (26) |

| S204A | 217 | (39) | 261 | (30) |

| V205A | 150 | 4 | NT | |

| L209A | 150 | 4 | 209 | (4) |

| E211K | 211 | (35) | 253 | (26) |

| A212V | 271 | (74) | NT | |

| R215A | 189 | (21) | NT | |

The second copy of traR or one of its mutant alleles expressed from derivatives of pZLQ constructed as described in Experimental procedures.

Tested in A. tumefaciens NTL4 harboring pRKLH4I41, which codes for wild-type traR and the TraR-dependent traG::lacZ reporter, and a pZLQ derivative.

Tested in A. tumefaciens NTL4 harboring pQKKR-lacZ10II, which codes for wild-type traR and the TraR-dependent traM::lacZ reporter, and a pZLQ derivative.

β-galactosidase activity expressed as units per 109 cfu as described in Experimental procedures. Each allele of traR was tested a minimum of three times, and the results shown are from a representative experiment.

% inhibition=100×{[wt+none]-[wt+mutant]}/[wt+none]. In this formula, [wt+none] and [wt+mutant] are levels of β-galactosidase activity in strains expressing only wild-type TraR or wild-type plus mutant TraR. The mutants that inhibited activation of the wild-type TraR by values greater than 20% are indicated in bold font.

Values in () indicate that the presence of the second traR allele results in levels of activation greater than wild-type traR alone.

NT= Not Tested.

We then tested the PC mutants for dominant-negativity on the Class I-promoter reporter. Most of these mutants displayed characteristics similar to their reaction on the Class II promoter (Table 3). All C-terminal PC mutants were recessive to wild-type TraR while the N-terminal mutants, D6G, D6R, D10A, K77A, S78A and G123A exhibited degrees of dominance over wild-type TraR (Table 3). However, the Class I-specific N-terminal PC mutants, including H46A, K74A, R79A, K80A and N122A, were recessive when co- expressed with wild-type TraR on the Class II promoter, but showed 26 to 38% dominant-negativity over wild-type TraR as assayed on the Class I promoter (Table 3), suggesting that those residues play a role in the interaction specifically with α during transcriptional activation from the Class I promoter.

TraR requires both α and σ70 from Agrobacterium to maximally activate transcription in E. coli

TraR fails to activate transcription of our Class II traG::lacZ reporter in E. coli unless co-expressed with the α-subunit from Agrobacterium (αAt) (Qin et al., 2004a). This dependence results from our observation that TraR has a lower affinity for the α-subunit from E. coli (αEc) than that from A. tumefaciens (Qin et al., 2004a). Considering the possibility that TraR is an ambidextrous activator, we assessed the effect of coexpressing σ70 from A. tumefaciens (σ70At) on TraR activation activity in E. coli. When co-expressed in E. coli with σ70At alone, TraR activated the traG::lacZ reporter to levels 3-5 fold higher as compared to cells expressing only TraR (Fig. S1 Insert). However, when co-expressed with αAt and σ70At, TraR activated the reporter to levels more than 100-fold higher than that of the E. coli cells expressing only the activator (Fig. S1). These results suggest that full activity of TraR on a class II promoter requires proper interactions with both αAt and σ70At.

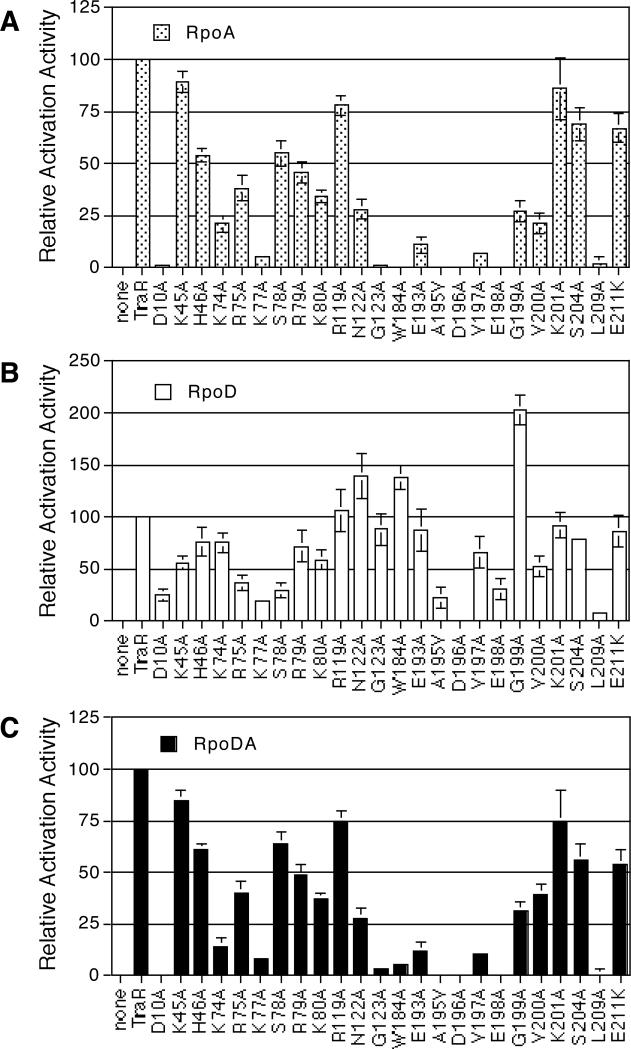

Genetic analysis of TraR PC mutants in interaction with αAt and σ70At

Using the E. coli genetic system described above we assessed whether our PC mutants are defective in interactions with αAt, with σ70At, or with both. To simplify the comparisons, activity for each mutant is expressed as percent of the background-corrected activity of wild-type TraR in each experimental set. To begin, we tested all of our activation-defective mutants of TraR in E. coli co-expressing αAt. As shown in Fig. 4A, TraR mutants D10A, K77A, G123A, W184A, A195V, D196A, V197A, E198A and L209A yielded levels of activation less than 10% of wild-type TraR; mutants K74A, V200A and E193A exhibited activities ranging between 10 and 25%; mutants R75A, R79A, K80A, N122A and G199A had activities between 25 and 50%; mutants H46A, S78A, S204A and E211K showed activities ranging from 50 to 75%; and mutants K45A, R119A and K201A showed activation levels at least 75% that of wild-type TraR.

Figure 4. Influence of components of A. tumefaciens RNA polymerase on activation in E. coli of a Class II promoter by TraR and its PC mutants.

Wild-type TraR and its PC mutant alleles, cloned in pQKK-I41 were tested for activation of the Class II traCDG::lacZ reporter in E. coli DH5α harboring either pZLQrpoA that expresses rpoAAt(A), pZLQatrpoD that expresses rpoDAt (B), or pZLQrpoDA that expresses both rpoAAt and rpoDAt (C). In all cases the cells were grown in the presence of 25 nM N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-l-HSL as described in Experimental procedures. Activity for each of the mutants is expressed as percent of the background–corrected activity of wild-type traR in each experimental set. The data represent the averages of three repetitions and error bars indicate standard deviations.

We then tested all of the mutants in E. coli co-expressing σ70At. As shown in Figure 4B, mutants K77A, A195V, D196A and L209A displayed 0 to 25% activity; mutants D10A, R75A, S78A and E198A yielded activities between 25 and 50%; and mutants K45A, H46A, K74A, R79A, K80A, V197A and V200A retained 50 to 75% activity of wild-type TraR. Mutants R119A, G123A, E193A, K201A, S204A and E211K activated the reporter to levels between 75 and 100% of wild type TraR, while mutants N122A, W184A and G199A yielded levels of activity higher than that of the wild-type activator (Fig. 4B).

In comparing the response of the PC mutants to co-expression of αAt with their response when co-expressed with σ70At, the N-terminal PC residues between positions 10 and 80 and C-terminal residues between positions 196 to 201 are about equally required for stimulation by both α and σ70, while residues between 119 and 193 are required for stimulation by α but not by σ70. Strikingly, G199A, although not identified as a PC mutant in the screen against our Class II promoter (Table 2), activated the reporter to levels more than two-fold higher than wild-type TraR in cells co-expressing σ70At (Fig. 4B). This enhanced level of activation most likely accounts for the much higher levels of activity of this mutant on Class II than on Class I promoters (Fig. 3). Consistently, a second mutant, S78A, that shows a lower activity on Class II as compared to Class I promoters (Fig. 3), exhibited a greater defect in σ70At-dependent activation as assayed in this genetic system (Fig. 4A and 4B).

When tested in E. coli co-expressing both αAt and σ70At, each mutant activated the traG::lacZ Class II reporter to relative levels virtually indistinguishable from those observed when tested in E. coli co-expressing only αAt (Fig. 4C). Although mutants including N122A, W184A and G199A showed a somewhat higher activity in E. coli when co-expressed with σ70At only, co-expressing both subunits of RNAP did not result in higher levels of activation (Fig. 4C).

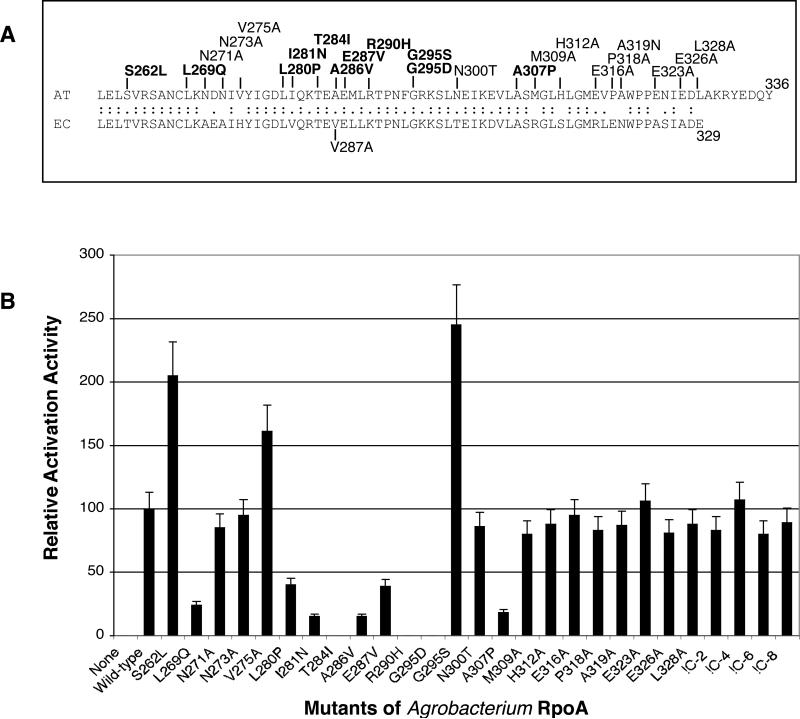

Residues of αCTD influencing TraR-mediated activation at Class II promoters

These results, combined with our previous studies (Qin et al, 2004a) strongly suggest that contact between the CTD of RpoAAt and TraR is essential for activation, prompting us to initiate an analysis of this region of the α-subunit. Of their shared residues, the CTDs of the α-subunits of A. tumefaciens and E. coli are 72% similar at the sequence level (Fig. 5A). However, RpoAAt contains an 8-residue extension at the C-terminus. Deleting between 2 and 8 residues of this extension resulted in no more than a 20% decrease in activation of the traG::lacZ reporter as tested in E. coli co-expressing σ70At (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Influence of single amino acid substitutions in the C-terminal domain of RpoAAt on TraR-mediated activation of transcription in E. coli.

Mutant alleles of rpoAAt, isolated as described in Experimental procedures were tested for their ability to stimulate TraR-mediated expression of the traCDG::lacZ reporter in E. coli. The amino acid sequence of the C-terminus of RpoAAt, the locations of the mutant residues, and the alignment with the C-terminus of RpoAEc are shown in panel A. Alleles in bold font represent mutations that have significant positive or negative effects on RpoAAt activity. The ability of each allele to stimulate transcriptional activation from pQKKR-I41 was tested in E. coli DH5α also expressing RpoDAt (panel B). Values representing β-galactosidase activities relative to that of wild-type RpoAAt are shown. The data represent the average of three repetitions with a deviation of less than 10%.

We then randomly mutagenized the C-terminal domain of rpoAAt and used our E. coli system to screen for alleles that were altered in their ability to stimulate TraR-mediated expression of the traG::lacZ reporter, all as described in Experimental procedures. From this screen we isolated nine mutants with single amino acid substitutions (Fig. 5A). Two such mutants, S262L and G295S stimulated levels of TraR activation to levels about twice that of wild-type RpoAAt when tested in the E. coli system. The remaining eight mutants, including L269Q, L280P, I281N, T284I, E287V, R290H, G295D and A307P yielded levels of stimulation of TraR-mediated activation ranging from 0 to 40% that of wild-type RpoAAt (Fig. 5B).

Of the nine randomly-generated mutants of RpoAAt, three represent residues that are variant in the E. coli ortholog (Fig. 5A). We then introduced by site-directed mutation substitutions in an additional 13 positions of the CTD of RpoAAt that are not conserved in RpoAEc (Fig. 5A). Eleven of the substitutions, including N271A, N273A, N300T, M309A, H312A, E316A, P318A, A319N, E323A, E326A and L328A had no significant effect on RpoAAt-mediated stimulation of TraR activity in E. coli (Fig. 5B). The V275A substitution increased the level of TraR-mediated activation about 1.6-fold while the A286V allele resulted in a close to 85% decrease in RpoAAt activity (Fig. 5B). The A286V substitution converts this residue to the corresponding Val-286 of the E. coli ortholog (Fig. 5A) raising the possibility that the failure of the E. coli α-subunit to support activation by TraR is linked to valine at this position. However, mutating Val-287 to alanine in RpoAEc did not confer on the E. coli α-subunit the ability to stimulate TraR-mediated activation (data not shown).

Discussion

In this work we have screened mutant alleles of TraR with alterations at 34 residues in the N- and C-terminal regions for those that have lost activation function but retain DNA binding activity. In these screens we used two assays to measure DNA binding activity: in vivo repression and in vitro gel retardation, and employed both Class I and Class II promoter-based reporters. From the current screen and previous studies (Qin, et al. 2004a) we have catalogued 22 mutants defining 20 residues with PC properties. Of these, 12 residues, D6, D10, H46, K74, R75, K77, S78, R79, K80, R119, N122, and G123 are located in the N-terminal domain while eight, W184, E193, D196, V197, E198, G199, K201 and E211 map to the C-terminal region of the protein. Mutations at 13 of these residues show PC properties in the closely related TraR protein (TraROct) from pTiR10 (White and Winans, 200; Costa, et al., 2009). However the two TraR orthologs exhibit some differences; four N-terminal PC residues of TraROct, Lys-7, Ala-13, Glu-15 and Ile-20 were not identified in TraR from pTiC58 while our studies identified two N-terminal residues, His-46 and Arg-119 not reported in TraROct. Similarly, we identified five C-terminal PC residues of TraR from pTiC58, Asp-196, Glu-198, Gly-199, Lys-201 and Glu-211 that were not reported to exhibit such properties in TraROct. Conversely, two C-terminal PC residues of TraROct, Lys-187 and Lys-189 (White and Winans, 2005; Costa, et al., 2009) were not identified in our study of TraR from the nopaline-type Ti plasmid. Of the three residues of LuxR described as exhibiting PC properties, Met-189, Glu-192 and Val-197 (Egland and Greenberg, 2001), a substitution at only Val-197 of TraRnop resulted in a PC phenotype (Table 2).

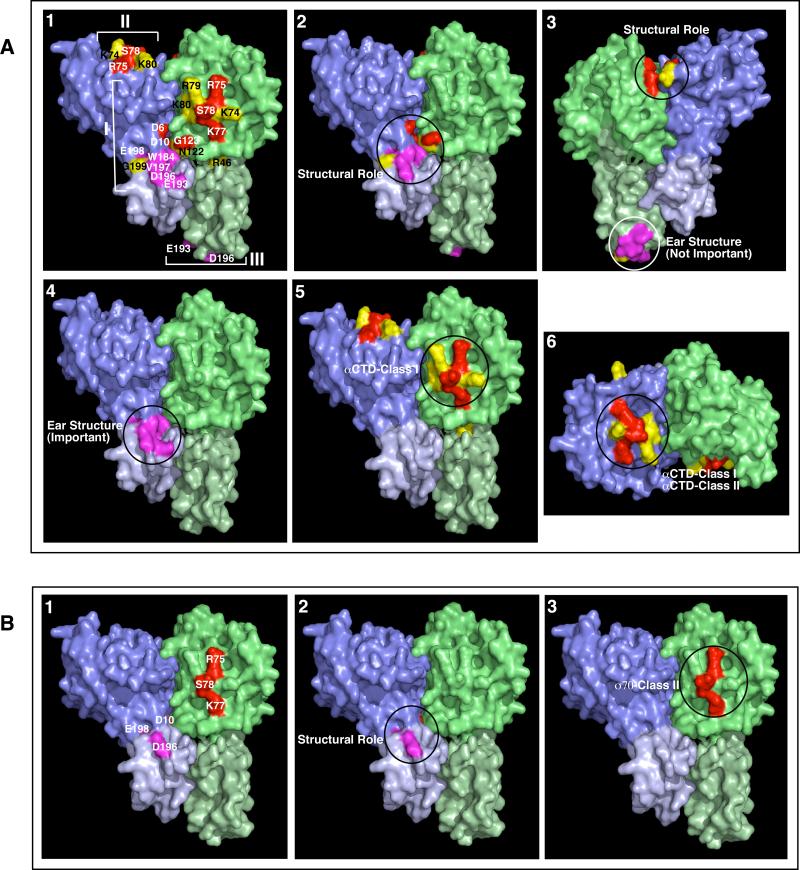

The positive control residues combine to form three distinct patches on the dimer structure of TraR

Several of the PC residues combine to form three surface patches on the dimer structure of TraR. As viewed down the DNA axis, Patch II is located on the top of the dimer, and Patches I and III are located near the DNA binding domain on the two lateral faces, left and right, of the dimer (Fig. 1C). Patch I, located in the left face of the dimer, is composed of Asp-6, Asp-10, Trp-184, Glu-193, Asp-196, Val-197, Glu-198 and Gly-199 from the compact protomer, and Asn-122 and Gly-123 as well as the other N-terminal residues from the extended protomer (Fig.1B) (Vannini et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002). Patch II, located on the top of the dimer, is made up of the N-terminal PC residues Asp-6 and Asp-10 from the extended protomer, and Asn-122 and Gly-123 as well as the other N-terminal PC residues from the compact protomer. Patch III, an isolated face on the right side of the dimer, is composed only of the C-terminal PC residues Trp-184, Glu-193, Asp-196, Val-197, Glu-198 and Gly-199 of the extended protomer (Fig.1B and 1C).

We previously reported that the D10A and G123A substitution mutants are strongly dominant-negative over wild-type TraR and that when co-expressed the two mutant alleles complement one another (Qin et al., 2004a), suggesting that both Patch I and Patch II are essential for activation. Consistent with this hypothesis, substitution mutations at all of the N-terminal PC residues contributing to the formation of these two patches exhibit dominant negativity (Table 3). Conversely, all of the C-terminal PC mutants were recessive when co-expressed with the wild-type TraR. These results suggest that Patches I and II, partially formed and exclusively formed by N-terminal PC residues respectively, are important for activation. However, the data suggest that Patch III, which is formed exclusively by C-terminal PC residues from the extended protomer, is not required for activation (Fig. 1C; Fig. 6A-3).

Figure 6.

Regions of TraR involved in interactions with components of RNA polymerase. Views 1-5 show locations of PC residues on the lateral faces while View 6 shows locations of residues on the top surface of TraR that play roles in interaction with the α (A) and σ70-subunits (B) of RNAP. Residues predicted to play structural roles, and those that form the ear structures in the C-terminal domains are shown in Views 2-4 of Panel A and View 2 of Panel B as indicated. In Panel A, View 3 is the back view of View 2 to indicate the difference of location of PC residues between the two protomers of a TraR dimer. The remaining PC residues colored in red and the Class I-specific PC residues colored in yellow, are shown in Views 5-6 of Panel A and View 3 of Panel B. Regions of TraR important for interactions with the C-terminal domain of RpoAAt at a Class I promoter, or with αCTD and RpoDAt at Class II promoters are circled and labeled as αCTD-Class I, αCTD-Class II and σ70-Class II respectively. The compact protomer is shown in purple while the extended protomer is shown in green. For each protomer, N-terminal residues are shown in a darker hue.

Clearly, the N-terminal domain of TraR is indispensable for activation function, a conclusion consistent with our analysis of N-terminal deletion derivatives (Qin et al., 2000; Luo et al., 2003) as well as a co-published study of TraROct (Costa et al., 2009). The requirement for specific N-terminal residues of both protomers for activation could explain our inability to isolate N-terminal truncated mutants of TraR that retain activity (Luo and Farrand, 1999). Given that such N-terminal deletion mutants of both LuxR and LasR retain the ability to activate (Choi and Greenberg, 1991; Kiratisin et al., 2002), our results suggest that TraR and other members of the LuxR family may differ in how they interact with RNA polymerase to activate transcription (Nasser and Reverchon, 2007). Alternatively, the N-terminal deletion mutants of LuxR and LasR may activate transcription by a mechanism different from that of the full-sized proteins (see Finney et al., 2002).

Discrimination between residues important for interaction of TraR with α from those important for interaction with σ70

Twelve of the 20 mutants with PC properties, including D6A, D10A, H46A, R75A, K77A, G123A, W184A, E193A, D196A, V197A, E198A, and G199 show significant (<80% of wild-type activity) defects on both Class I and Class II promoters, suggesting that these mutants are compromised in their interactions with the α-subunit (Fig. 3). Consistent with this hypothesis, these mutants showed reduced activity from our Class II promoter in E. coli co-expressing αAt (Fig. 4A). However, when co-expressed with σ70At only seven of these 12 mutants, including D10A, H46, R75A, K77A, D196A, V197A and E198A, showed decreased levels of activity as compared to that of wild-type TraR. Three mutants, G123A, W184A and E193A, showed no significant defect in cells co-expressing σ70At only while one mutant, G199A was hyperstimulated by co-expressed σ70At (Fig. 4B). We propose that the seven mutants define residues important for interactions with both αAt and σ70At while the remaining four mutants define residues that contribute to interactions exclusively with αAt on Class II promoters. Three additional mutants, S78A, K201A and E211K show significant defects on Class II but less so on Class I promoters (Fig. 3). We suggest that these three residues are important for interactions between TraR and σ70At and perhaps also αAt. Of the remaining five mutants, three, K74A, R79A and K80A show defects only on the Class I promoter (Fig. 3) and were stimulated by co-expressed σ70At but not αAt (Fig. 4A and B) suggesting that these three residues contribute to interactions with RpoA but not Sigma-70. The last two PC mutants, R119A and N122A show similar levels of defects on both promoters (Fig. 3). The R119A mutant is strongly stimulated by both RNAP subunits while the N122A mutant is stimulated strongly by σ70At but not by αAt (Fig. 4A and B). In summary, of the 20 PC mutants, seven, H46A, K74A, R79A, K80A, R119A N122A, and G199A are specific to the Class I promoter. Ten of the remaining mutants define residues that are important for activation at both Class I and Class II promoters, while three mutants, S78A, K201A and E211K identify residues that are disproportionately important for activation of a Class II promoter.

Considering the activity of the PC mutants in response to the co-expression of αAt or σ70At in E. coli, we mapped the residues important for interactions with α or with σ70 on the crystal structure of the dimeric DNA-bound activator. As shown in Fig. 6A-1, TraR residues that are important for αAt-dependent activation in E. coli combine to form two surface patches that co-locate with Patch I and Patch II in Figure 1. Those residues that are important for σ70At-dependent activation form two Ler patches that overlap with the α-patches (Fig. 6B-1).

Based on these results alone, we cannot discriminate between effects arising from direct molecular interactions and indirect effects due to conformational changes in the mutant proteins. Several of the PC residues may play roles in maintaining the structure of either the monomers or the dimeric form of TraR. For example, there are at least two direct contacts made by PC residues within the N-terminal domains between the two protomers; a salt bridge between Asp-6 and Lys-119 and a hydrogen bond between Asp-10 and the amide of Asn-122 (Vannini et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002, Fig. 6). In addition, several residues participate in contacts between the N- and C-terminal domains within the compact monomer of the TraR dimer including two salt bridges (Lys-7 and Glu-198, Asp-27 and Lys-177) and two hydrogen bonds (His-31 to the carbonyl of Gly-199, and Arg-183 to the carbonyl of Ala-13) (Figs. 1 and 6, Vannini et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002). This structural information suggests that certain PC residues including Asp-6, Asp-10, Asn-122, Glu-198 and Gly-199 and those very close to these structural residues including Gly-123, Trp-184, Asp-196 and Val-197 may play roles in maintaining the interactions between the N-and C-terminal domains (Fig. 6A-2, 3 and 6B-2).

The C-terminal region of TraR forms an eared helix with the scaffolding helices protruding from the main dimeric structure (Fig. 1C). Again due to its strong asymmetry, one such ear is juxtaposed next to the left lateral face formed by the N-terminal domain of the compact protomer (Fig. 6A-2, 4), while the other ear contributes to the C-terminal apex of the extended protomer on the right face of the dimer (Fig. 1C, Fig. 6A-3). Five residues with PC properties, Trp-184, Glu-193, Asp-196, Val-197 and Glu-198 all contribute to the structure of the ears (Fig. 1B and C, Fig. 6A-4). Mutants at D196A and E198A completely lost activation functions on both Class I and Class II promoters (Fig. 3) suggesting that these two residues play a structural role (Fig. 6A-2; 6B-2). That Glu-198 participates in a salt bridge with Lys-7 is consistent with this interpretation. The remaining four residues, in conjunction with the patch formed by the N-terminal PC residues form the lip of a pocket on the lateral face of the dimer (Fig. 1; Fig. 6). We propose that this pocket represents one site at which α- or σ70- subunits interact with the dimeric activator. Given that all five mutants are recessive to wild-type TraR, only one ear appears essential. We propose that the second ear in close juxtaposition to Patch III, located at the lower apex of the extended protomer, does not participate in interactions with RNA polymerase (Fig. 1C; Fig. 6A-3).

Excluding the residues that may play a conformational role in TraR as well as those that contribute to the C-terminal ear structure within the compact protomer, only three PC residues in the N-terminal region, R75, K77 and S78, remain which are required for TraR-mediated activation from both Class I and II promoters (Fig. 3). We suggest that these three residues contribute, in part, to the interaction interface on TraR for RNAP (Fig. 6A-5, 6; 6B-3). The R75A mutant showed similar levels of defect on both promoters (67% on Class I and 77% on Class II, see Fig. 3) as well as a similar decrease of activation in E. coli expressing either αAt or σ70At (38% for αAt and 37% for σ70At, see Fig. 4). The K77A mutant showed decreased levels of activation on both promoters but showed the greatest defect on the Class I promoter (15% as compared to 45% on Class II; see Fig. 3). This mutant also consistently showed a lower level of response when co-expressed with αAt than σ70At in E. coli (Fig. 4). The alanine substitution at S78 affected activation activities on both reporters, but showed a considerably greater effect on Class II (59%) as compared to Class I (87%) promoters (Fig. 3). This mutant also consistently showed a greater defect in activation when co-expressed with σ70At as compared to αAt (Fig. 4). Based on these results, we propose that the two nearly identical patches formed by R75, K77 and S78 on the two protomers play two roles in the interaction between TraR and RNAP (Fig. 6A-5, 6 and 6B-3). We predict that during activation from Class II promoters, the R75-K77-S78 patch located on the top of the TraR dimer is required for interaction with the CTD of one copy of α-subunit (Fig. 6A-6), while the other patch, located on the front face of the TraR dimer within Patch I is important for interaction with σ70 (Fig. 6B-3). However, both patches in conjunction with the flanking Class I promoter-specific PC residues may contribute to interactions with the C-terminal domains of both α-subunits during activation from Class I promoters (Fig. 6A-5, 6).

Under conditions in which only αAt or only σ70At is co-expressed, TraR weakly activates a Class II promoter in E. coli (Fig. S1). However, co-expressing both subunits from A. tumefaciens, results in levels of activation much higher than the sum of those obtained when only one or the other subunit is co-expressed (Fig. S1). This observation suggests that the TraR-mediated activation at Class II promoters resembles that of FNR or CAP, requiring interactions with both α and σ70-subunits (Bell and Busby, 1994; Rhodius and Busby, 2000; Li et al., 1998; Lawson et al., 2004). Consistent with this hypothesis, purified DNA-bound TraR complexes interact directly with α- (Qin et al., 2004a) and with σ70-subunits respectively (Qin and Farrand, unpublished data). However, while the relative activation levels of each TraR PC mutant in E. coli co-expressing both αAt and σ70At are virtually identical to those observed in cells co-expressing only αAt, there was little correlation with levels of activation in cells co-expressing only σ70At (Fig. 4B). These results imply that, although interactions of TraR with αAt and with σ70At are both important, the interaction with αAt is the predominant determinant required for activation of Class II promoters by TraR, a conclusion consistent with studies of TraROct (Costa, et al., 2009).

Regions of the CTD of RpoA from A. tumefaciens required for activation by TraR

Studies with CAP have identified three domains of RpoAEc important for activation. The 265 domain (Savery, et al., 1998; reviewed in Rodius and Busby, 1998), composed of nine residues, is 100% conserved in RpoAAt while the 261 and 287 domains of the two RpoA proteins share 3 of 4 and 5 of 9 residues in common (Fig. 5A). Of the nine mutants of RpoAAt defective in stimulating TraR-mediated activation in E. coli (Fig. 5B), four, T284I, A286V, E287V and R290H are surfaced-exposed (Fig. S2) and map to the 287 determinant. Of these, Thr-284, Ala-286 and Glu-287 correspond to three of the six residues of RpoAEc that make direct contacts with CAP (Benoff, et al., 2002). On the other hand, only one of our mutants, G295D, corresponds to the six residues of RpoAEc required for transcriptional activation by LuxR (Finney et al., 2002). Overall, these results suggest that, as in the case of the CAP-RpoAEc interaction, the 287 region of RpoAAt is important for making contact with TraR. However, an alanine substitution at Glu-316, corresponding to a fourth CAP-interaction residue in the 287 region of RpoAEc had no effect on stimulation of TraR-mediated activation. Remarkably, substitutions at three sites in RpoAAt, Ser-262, Val-275 and Gly-295, resulted in stimulation of TraR activity to levels 1.6 to 3 times higher than wild-type in E. coli (Fig. 5B). Gly-295 is of particular interest; an aspartate substitution results in a mutant of RpoAAt unable to stimulate transcription by TraR while a serine substitution yields a mutant that supports higher than wild-type activation. Two of these residues lie close to or within the 265 domain, a region of the α-subunit of E. coli involved in interactions with DNA (Busby and Ebright, 1999; Lawson et al., 2004). These results are consistent with our conclusions that interactions with RpoA are critical for TraR-mediated induction of transcription and further suggest that TraR may mediate interactions between the α-subunit and the promoter regions of TraR-dependent genes that facilitate activation of transcription.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and media

A. tumefaciens strain NTL4 (Luo et al., 2001) and Escherichia coli strains DH5α and S17-1 were used for all constructions and most experiments. E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (pLysS), harboring the appropriate plasmids, was used for overexpression and purification of native TraR and its mutants. DH5α was used to monitor TraR activation activities in E. coli co-expressing αAt, σ70At or both.

E. coli strains were grown in Luria broth (Invitrogen) at 37 °C or in minimal medium A containing glucose as sole carbon source at 28°C (Miller, 1972). A. tumefaciens strains were grown at 28 °C on nutrient agar (Difco), in MG/L medium (Cangelosi et al., 1991), or in AB minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% mannitol (ABM medium) as sole carbon source (Chilton et al., 1974). When required, antibiotics were added to the media at the concentrations described previously (Farrand et al., 1996). X-Gal (Sigma) was included in the media at 40 μg/ml to monitor expression of lacZ reporter genes. IPTG (Sigma) was added at 100 μM to induce expression of traR when necessary. Synthetic 3-oxo-C8-HSL [N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-L-homeserine lactone] from Sigma was added to cultures at concentrations as indicated in the text.

Reporter plasmids

Plasmid pH4I41, a derivative of pCP13/B which harbors a traG::lacZ transcriptional fusion (Luo and Farrand, 1999), was used as the Class II-promoter reporter for TraR activation. Plasmid pRKLH4I41, a derivative of pRK415 that contains traR and the traG::lacZ transcriptional fusion (Luo et al., 2003), was used as the Class II-promoter reporter for assays of dominant negativity. Plasmids pQKK-lacZ10II and pQKKR-lacZ10II, two derivatives of pQKK harboring a traM::lacZ transcriptional fusion, were used as the Class I-promoter reporters for TraR activation and for dominant negativity assays respectively. pQKK-lacZ10II and pQKKR-lacZ10II were constructed by cloning into pQKK (Qin et al., 2004a) and pQKKR (Qin et al., 2004a) a HindIII fragment obtained from pMP1 (Hwang et al., 1995), which harbors an insertion of Tn3HoHo1 at the start of the traM gene. The repression reporter pPBL1, in which the 18bp tra box is centered at the −10 region of a promoter driving expression of lacZ in E. coli, was used to measure the DNA binding activity of TraR and its mutant proteins in vivo (Luo et al., 1999).

Construction of plasmids expressing αAt, σ70At, or both αAt and σ70At

Plasmid pZLQrpoA expressing αAt was constructed by cloning into pZLQ an NdeI-BamHI fragment encoding RpoAAt as described previously (Qin et al., 2004a). Plasmids expressing σ70At, or both αAt and σ70At were constructed as follows. Agrobacterium rpoD (rpoDAt, Atu2187) was amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase and Agrobacterium genomic DNA as template. The resulting fragment was engineered to contain an NdeI site within the start codon and a BamHI site just distal to the stop codon of the rpoDAt gene. This coding region of rpoDAt was then cloned between the NdeI and BamHI sites of pZLQ to generate pZLQatrpoD expressing σ70At. In addition, a new BamHI-BamHI fragment of rpoAAt containing a BamHI site 5′ to the start codon was generated by PCR using pZLQrpoA as template. This new rpoA fragment was cloned into pZLQatrpoD at the BamHI site to generate pZLQrpoDA that expresses both σ70At and αAt.

DNA manipulations

Recombinant DNA techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al (2001). Plasmid DNA was isolated by alkaline lysis or using a miniprep kit from QIAGEN Inc. according to the manufacturer's instructions. Digestions with restriction endonucleases were carried out as described by the manufacturers of the enzymes. Plasmid DNA was introduced into E. coli by calcium chloride-mediated transformation and into A. tumefaciens by electroporation or by biparental matings from E. coli S17-1 (Mesereau et al., 1990; Dessaux et al., 1989)

Mutagenesis of traR

traR D6G and D6R were generated by error-prone PCR. The other substitution mutations in traR were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange Kit (Stratagene) or generated by chemical treatment with hydroxylamine as described previously (Luo et al., 2000). The validity of all mutant constructs was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis performed by the Center of Core Sequencing Facility at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Mutagenesis of αCTD

A DNA fragment encoding the C-terminal 81 amino acids (255-336) of αAt and engineered to contain a SacI site at the 5′-end and an XbaI site at the 3′-end was amplified by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase. This αCTDAt fragment was cloned into pBlueScript(SK) to generate pSKαCTD. We also made a similar construct called pSKECαCTD that harbors the C-terminal 73 amino acids (256-328 aa) of αEc. We then used pSKαCTD or pSKECαCTD as template to perform error-prone PCR and site-directed mutagenesis to produce mutated fragments called αCTD*. These mutant fragments were digested with SacI and XbaI, and cloned into a trapper plasmid pQESHrpoDA-CTD, a derivative of pZLQrpoDA in which nucleotides encoding the C-terminal 81 amino acids of αAt were deleted and replaced with the SacI-HindIII MCS region of pUC18. The resulting constructs, named pQESHrpoDA-CTD*, were screened for mutant phenotypes following electroporation into the reporter strain NTL4(pQKKR-I41). The validity of all mutants was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Quantitative assays for activation, and dominant negativity properties

The activation properties of TraR and its mutants cloned into pZLQ were assessed using the Class II-promoter reporter strain NTL4 (pH4I41) (Luo and Farrand, 1999) and Class I-promoter strain NTL4 (pQKK-lacZ10II) respectively. The dominant-negative properties of TraR substitution mutants cloned into pZLQ were assessed using the Class II-promoter reporter NTL4 (pRKLH4I41) (Luo et al., 2003) and the Class I-promoter reporter NTL4 (pQKKR-lacZ10II). In all cases, strains were cultured in MG/L medium with or without 50 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL.

Quantitative assays for repression and activation activity in E. coli

The ability of the mutant alleles to bind DNA in vivo was assessed using a repression assay with DH5α (pPBL1) (Luo and Farrand, 1999). In this strain, TraR and its mutants cloned in the vector pZLQ were used to represses expression of a lacZ fusion encoded by pPBL1 in the presence of 50 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL (Luo and Farrand, 1999).

TraR and its mutant alleles were assessed for activation activities in E. coli DH5α harboring the Class II-promoter reporter plasmid pQKKR-I41 (Qin et al., 2004a) encoding traR or its mutant gene, and one of these pZLQ derivatives, pZLQrpoA, pZLQatrpoD or pZLQatrpoDA, which encodes αAT, σ70AT, or both αAT and σ70AT respectively.

β-Galactosidase assays

Production of β-galactosidase by A. tumefaciens and E. coli strains was quantified using a modification of the method of Miller (Miller, 1972) as previously described (Cook and Farrand, 1992). Activity is expressed as Miller units or units of enzyme/109 colony-forming units. Samples were assayed in triplicate, and experiments were repeated at least twice. In the absence of error bars or values of variation, results from a single representative experiment are shown.

Western analysis

The stability and expression levels of TraR mutant proteins in vivo as well as the amount of purified TraR protein used in gel mobility shift assays were determined by Western analysis using anti-TraR antiserum as described previously (Qin et al., 2004b).

Gel retardation assays

Purified dimeric TraR or its mutant derivatives from the cleared cell extracts, following normalization by western analysis, were prepared at a series of two-fold dilutions and incubated together with a DIG-labeled 251 bp DNA probe containing an intact tra box sequence (20 ng) at room temperature in 20 μl of reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 60 mM KCl, 30 μg ml-1 salmon sperm DNA, 20 μg ml-1 BSA, 0.05% Tween 20 and 10% glycerol) for 20 min (Qin et al., 2004b). The samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 0.25×TBE buffer (1×TBE: 89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) on 7.5% native polyacrylamide gels. The separated DNA fragments and DNA–protein complexes were electroblotted onto positively charged nylon membranes and visualized by chemiluminescence as described previously (Qin et al., 2000).

Structural analyses

The three-dimensional structures of TraR and αCTDs were analyzed using PyMOL Version 10.2 on a Macintosh. The coordinates for the structure of TraR from pTiR10 used in these analyses are available in the Protein Data Bank under code IL3L (Zhang et al., 2003). An in silico crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of RpoAAt was constructed by threading the sequence of residues 243-336 of RpoAAt to the crystal structure of the homologous region of RpoAEc available in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 1LB2 (Benoff, et al. 2002) using the Swiss Model Server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grant No. R01 GM52465 from the NIH to S.K.F.

References

- Bell A, Busby S. Location and orientation of an activating region in the Escherichia coli transcription factor, FNR. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoff B, Yang H, Lawson CL, Parkinson G, Liu J, Blatter E, et al. Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP–alpha CTD–DNA complex. Science. 2002;297:1562–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1076376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S, Ebright RH. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:853–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2771641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S, Ebright RH. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J Mol Biol. 1999;293:199–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi GA, Best EA, Martinetti G, Nester EW. Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:384–397. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton MD, Currier TC, Farrand SK, Bendich AJ, Gordon MP, Nester EW. Agrobacterium tumefaciens DNA and PS8 bacteriophage DNA not detected in crown gall tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3672–3676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Greenberg EP. The C-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein contains an inducer-independent lux gene activating domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11115–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DM, Farrand SK. The oriT region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid pTiC58 shares DNA sequence identity with the transfer origins of RSF1010 and RK2/RP4 and with T-region borders. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6238–6246. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6238-6246.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ED, Hongbaek C, Winans SC. Identification of amino acid residues of he pheromone-binding domain of the transcription factor TraR that are required for positive control. Mol Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06755.x. (ePublished ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danino VE, Wilkinson A, Edwards A, Downie JA. Recipient-induced transfer of the symbiotic plasmid pRL1JI in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae is regulated by a quorum-sensing relay. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:511–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaux Y, Petit A, Ellis JG, Legrain C, Demarez M, Wiame JM, et al. Ti plasmid-controlled chromosome transfer in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6363–6366. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6363-6366.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egland KA, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri: Analysis of the LuxR DNA binding region by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:382–386. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.382-386.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrand SK, Hwang I, Cook DM. The tra region of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid is a chimera with elements related to the transfer systems of RSF1010, RP4, and F. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4233–4247. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4233-4247.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney AH, Blick RJ, Murakami K, Ishihama A, Stevens AM. Role of the C-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in LuxR-dependent transcriptional activation of the lux operon during quorum sensing. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4520–4528. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4520-4528.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Burbea M, Winans SC. Activity of the Agrobacterium Ti plasmid conjugal transfer regulator TraR is inhibited by the product of the traM gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1367–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1367-1373.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Greenberg EP. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C, Winans SC. Localization of OccR-activated and TraR-activated promoters that express two ABC-type permeases and the traR gene of Ti plasmid pTiR10. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1199–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Chang W, Pierce DL, Seib LO, Wagner J, Fuqua C. Quorum sensing in Rhizobium sp. strain NGR234 regulates conjugal transfer (tra) gene expression and influences growth rate. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:809–822. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.809-822.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Li PL, Zhang L, Piper KR, Cook DM, Tate ME, Farrand SK. TraI, a LuxI homologue, is responsible for production of conjugation factor, the Ti plasmid N-acyl homoserine lactone autoinducer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4639–4643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Cook DM, Farrand SK. A new regulatory element modulates homoserine lactone-mediated autoinduction of Ti plasmid conjugal transfer. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:449–458. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.449-458.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DC, Ishihama A, Stevens AM. Involvement of region 4 of the sigma-70 subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation of the lux operon during quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;228:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00750-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiratisin P, Tucker KD, Passador L. LasR, a transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes, functions as a multimer. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4912–4919. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.17.4912-4919.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori H, Inagaki S, Yoshioka S, Aono S, Higuchi Y. Crystal structure of CO-sensing transcription activator CooA bound to exogenous ligand imidazole. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:864–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson CL, Swigon D, Murakami KS, Darst SA, Berman HM, Ebright RH. Catabolite activator protein: DNA binding and transcription activation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Wing H, Lee D, Wu HC, Busby S. Transcription activation by Escherichia coli FNR protein: similarities to, and differences from, the CRP paradigm. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2075–2081. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Moyle H, Susskind MM. Target of the transcriptional activation function of phage lambda cI protein. Science. 1994;263:75–77. doi: 10.1126/science.8272867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PL, Farrand SK. The replicator of the nopaline-type Ti plasmid pTiC58 is a member of the repABC family and is influenced by the TraR-dependent quorum-sensing regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:179–188. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.179-188.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z-Q, Clemente TE, Farrand SK. Construction of a derivative of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 that does not mutate to tetracycline resistance. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:98–103. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z-Q, Farrand SK. Signal-dependent DNA binding and functional domains of the quorum-sensing activator TraR as identified by repressor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9009–9014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z-Q, Qin Y, Farrand SK. The antiactivator TraM interferes with the autoinducer-dependent binding of TraR to DNA by interacting with the C-terminal region of the quorum-sensing activator. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7713–7722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZQ, Smyth AJ, Gao P, Qin Y, Farrand SK. Mutational analysis of TraR. Correlating function with molecular structure of a quorum-sensing transcriptional activator. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13173–13182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marketon MM, Gonzalez JE. Identification of two quorum-sensing systems in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3466–3475. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3466-3475.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersereau M, Pazour GJ, Das A. Efficient transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by electroporation. Gene. 1990;90:149–151. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90452-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi K, Maeda Y, Satou M, Hardayani NS, Kataoka M, Tanaka N, Yoshida K. The complete nucleotide sequence of a plant root-inducing (Ri) plasmid indicates its chimeric structure and evolutionary relationship between tumor-inducing (Ti) and symbiotic (Sym) plasmids in Rhizobiaceae. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:771–784. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser W, Reverchon S. New insights into the regulatory mechanisms of the LuxR family of quorum sensing regulators. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0702-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W, Zhou Y, Dong Q, Ebright Y, Ebright R. Characterization of the activating region of Escherichia coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP) I. Saturation and alanine-scanning mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:595–602. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W, Kim Y, Tau G, Heyduk T, Ebright RH. Transcription activation at class II CAP-dependent promoters: two interactions between CAP and RNA polymerase. Cell. 1996;87:1123–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81806-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas KM, Winans SC. A LuxR-type regulator from Agrobacterium tumefaciens elevates Ti plasmid copy number by activating transcription of plasmid replication genes. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1059–1073. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto UM, Winans SC. Dimerization of the quorum sensing transcription factor TraR enhances resistance to cytoplasmic proteolysis. Mol Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06730.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper KR, Beck von Bodman S, Farrand SK. Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature. 1993;362:448–450. doi: 10.1038/362448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Luo Z-Q, Smyth AJ, Gao P, Beck von Bodman S, Farrand SK. Quorum-sensing signal binding results in dimerization of TraR and its release from membranes into the cytoplasm. EMBO J. 2000;19:5212–5221. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Luo ZQ, Farrand SK. Domains formed within the N-terminal region of the quorum-sensing activator TraR are required for transcriptional activation and direct interaction with RpoA from Agrobacterium. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:40844–40851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Smyth AJ, Su S, Farrand SK. Dimerization properties of TraM, the antiactivator that modulates TraR-mediated quorum-dependent expression of the Ti plasmid tra genes. Mol Microbiol. 2004b;53:1471–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Su S, Farrand SK. Molecular basis of transcriptional antiactivation. TraM disrupts the TraR-DNA complex through stepwise interactions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19979–19991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, Busby SJW. Positive activation of gene expression. Curr Op Microbiol. 1998;1:152–159. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, Busby SJ. Transcription activation by the Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein: determinants within activating region 3. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:295–310. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodius VA, West DM, Webster CL, Busby SJ, Savery NJ. Transcription activation at class II CRP-dependent promoters: the role of different activating regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:326–332. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Savery NJ, Lloyd GS, Kainz M, Gaal T, Ross W, Ebright RH, Gourse RL, Busby SJW. Transcriptional activation at Class II CRP-dependent promoters: identification of determinants in the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit. EMBO J. 1998;17:3439–3447. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens AM, Dolan KM, Greenberg EP. Synergistic binding of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR transcriptional activator domain and RNA polymerase to the lux promoter region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12619–12623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens AM, Fujita N, Ishihama A, Greenberg EP. Involvement of the RNA polymerase alpha-subunit C-terminal domain in LuxR-dependent activation of the Vibrio fischeri luminescence genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4704–4707. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4704-4707.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott AE, Stevens AM. Amino acid residues in LuxR critical for its mechanism of transcriptional activation during quorum sensing in Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:387–392. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.387-392.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun-Garrido C, Bustos P, González V, Brom S. Conjugative transfer of p42a from Rhizobium etli CFN42, which is required for mobilization of the symbiotic plasmid, is regulated by quorum sensing. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1681–1692. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1681-1692.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini A, Volpari C, Gargioli C, Muraglia E, Cortese R, De Francesco R, Neddermann P, Marcom SD. The crystal structure of the quorum sensing protein TraR bound to its autoinducer and target DNA. EMBO J. 2002;21:4393–4401. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CE, Winans SC. Identification of amino acid residues of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens quorum-sensing regulator TraR that are critical for positive control of transcription. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1473–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CE, Winans SC. The quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR decodes its DNA binding site by direct contacts with DNA bases and by detection of DNA flexibility. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:245–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead NA, Barnard AM, Slater H, Simpson NJ, Salmond GP. Quorum-sensing in gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:365–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SM, Savery NJ, Busby SJ, Wing HJ. Transcription activation at class I FNR-dependent promoters: identification of the activating surface of FNR and the corresponding contact site in the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4028–4034. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.20.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheleznova-Heldwein EE, Brennan RG. Crystal structure of the transcription activator BmrR bound to DNA and a drug. Nature. 2001;409:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35053138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Murphy PJ, Kerr A, Tate ME. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Nature. 1993;362:446–448. doi: 10.1038/362446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RG, Pappas T, Brace JL, Miller PC, Oulmassov T, Molyneaux JM, et al. Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA. Nature. 2002;417:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nature00833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Merkel T, Ebright R. Characterization of the activating region of Escherichia coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP) II. Role at Class I and Class II CAP-dependent promoters. J Mol Biol. 1994;243:603–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Winans SC. Autoinducer binding by the quorum-sensing regulator TraR increases affinity for target promoters in vitro and decreases TraR turnover rates in whole cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4832–4837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.