Abstract

A bifunctional version of PCTA (3,6,9,15-tetraazabicyclo[9.3.1]pentadeca-1(15),11,13-triene-3,6,9,-triacetic acid) that exhibits fast complexation kinetics with the trivalent lanthanide(III) ions was synthesized in reasonable yields starting from N, N′, N″-tristosyl-(S)-2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine. pH-potentiometric studies showed that the basicities of p-nitrobenzyl-PCTA and the parent ligand PCTA were similar. The stability of M(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (M = Mg2+, Ca2+, Cu2+, Zn2+) complexes was similar to that of the corresponding PCTA complexes while the stability of Ln3+ complexes of the bifunctional ligand is somewhat lower than that of PCTA chelates. The rate of complex formation of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes was found to be quite similar to that of PCTA, a ligand known to exhibit the fastest formation rates among all lanthanide macrocyclic ligand complexes studied to date. The acid catalyzed decomplexation kinetic studies of the selected Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes showed that the kinetic inertness of the complexes was comparable to that of Ln(DOTA) chelates making the bifunctional ligand NO2-Bn-PCTA suitable for labeling biological vectors with radioisotopes for nuclear medicine applications.

INTRODUCTION

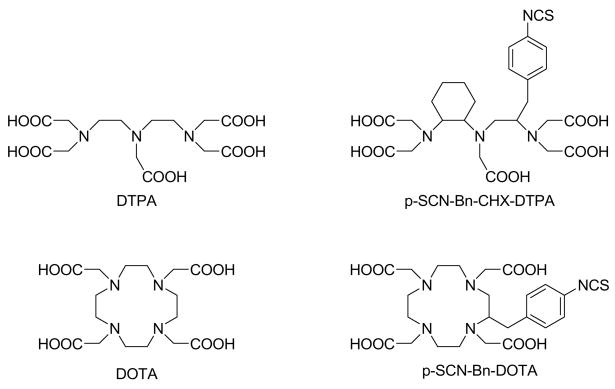

The choice of chelating system for biomedical imaging and therapeutic applications is largely determined by the nature of the metal ion required for the given application. Several rare earth metal ions (lanthanides and yttrium) and main group III elements are frequently selected for diagnostic (111In, 67Ga, 68Ga, 86Y, 177Lu) and/or therapeutic (90Y, 177Lu, 166Ho, 149Pm, 153Sm) nuclear medicine applications.(1, 2) A common characteristic feature of these metals is their tendency to exist as trivalent cations that form stable complexes in aqueous media with polyamino polycarboxylate type ligands such as the acyclic H5DTPA (diethylenetriamine-N, N, N′, N″, N″-pentaacetic acid) and the macrocyclic H4DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-teraacetic acid) systems (Figure 1). Bifunctional derivatives of DOTA are increasingly used to radiolabel peptides, proteins and other biomolecules.(3) The success of DOTA-bifunctionals is largely due to their ability to form complexes with these metal ions with high thermodynamic stability and extraordinary kinetic inertness. However, slow complex formation kinetics with DOTA under mild conditions can be a disadvantage, especially when sensitive biological vectors are labeled or when short half-lived isotopes are used.(4, 5) Therefore, macrocyclic ligands that complex radioisotopes faster than DOTA and still retain reasonably high kinetic inertness are very desirable. The acyclic octadentate DTPA and its bifunctional versions form complexes much faster than DOTA derivatives but these complexes have significantly lower kinetic inertness than the corresponding DOTA derivatives despite recent improvements achieved by substituting one of the flexible ethane-1,2-diamine units of DTPA by the more rigid propane-1,2-diamine (MX-DTPA) or cyclohexane-1,2-diamie bridge (CHX-DTPA) (Figure 1). (6)

Figure 1.

DTPA and DOTA and two bifunctional derivatives commonly used in nuclear medicine.

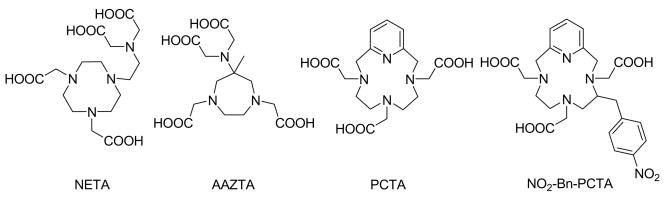

Recently, a few attempts have been reported to overcome the problem of slow complex formation involving DOTA-based ligands (Figure 2). Brechbiel and co-workers have synthesized a new class of ligands that integrate a macrocyclic triazacyclononane-diacetic acid and acyclic iminodiacetic acid moiety (bimodal or “hybrid” ligands). When the two units are linked together through an ethylene bridge, the resulting ligand (NETA) was shown to have improved complexation kinetics (fast complexation with Y3+, excellent serum stability and rapid clearance of the radiolanthanide chelates).(7) A bifunctional version of NETA has also been reported recently.(4, 8)

Figure 2.

Structure of NETA, AAZTA, PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA.

Aime and colleagues synthesized an interesting cyclic heptadentate ligand, AAZTA.(9) The authors have not reported detailed equilibrium and kinetic data for this system but it was noted that the reaction of AAZTA with lanthanides was almost instantaneous.(9)

Our approach to a bifunctional macrocyclic chelator with improved metal ion complexation kinetics is based on the ligand H3PCTA (3,6,9,15-tetraazabicyclo[9.3.1]pentadeca-1(15),11,13-triene-3,6,9-triacetic acid, Figure 2). We recently reported that PCTA forms complexes with lanthanide ions about an order of magnitude faster than DOTA.(10) Furthermore, the acid catalyzed dissociation rates of the Ln(PCTA) complexes were found to be satisfactorily slow despite their somewhat low thermodynamic stabilities.(10) Here we report the synthesis of a bifunctional version of PCTA, (NO2-Bn-PCTA), the protonation constants of the ligand, the stability constants of the ligand with various metal ions and the formation and dissociation rates of some Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis

The detailed synthetic procedures for the bifunctional ligand (S)-5-(p-nitrobenzyl)-PCTA (NO2-Bn-PCTA) is reported in the Supplementary Information. Analytically pure samples of the ligand used in the equilibrium and kinetics studies were obtained by preparative HPLC purification on Phenomenex® Luna 5u C18(2) column [elution with H2O (0.038% HCl): MeCN (gradient elution from 0% MeCN to 50% MeCN in 30 minutes)].

Equilibrium studies

pH-potentiometric titrations were carried out with a Thermo Orion EA940 expandable ion analyzer using Thermo Orion semi-micro combination electrode 8103BN in a thermostated (at 25.0°C) vessel. A Metrohm DOSIMATE 665 autoburette (5 mL capacity) was used for base additions and 1.0 M KCl was used to maintain the ionic strength. All equilibrium measurements (direct titrations) were carried out in 10.00 mL sample volumes with magnetic stirring. During the titrations, argon gas was passed over the sample surface to maintain a CO2-free environment. Standard buffers (Borax: 0.01 M, pH = 9.180 and KH-phthalate 0.05 M, pH = 4.005) were used to calibrate the electrode. The titrant, a carbonate-free KOH solution, was standardized against 0.05 M KH-phthalate solution by pH-potentiometry. The H+ ion concentrations corresponding to the measured pH values were calculated by the method proposed by Irving et al.(11) The ion-product of water was established in a separate acid-base titration experiment (pKw=13.747) and used in our calculations.

Stock solutions of MgCl2, CaCl2, ZnCl2, CuCl2, YCl3, InCl3 and LnCl3 were prepared from analytical grade salts (Aldrich and Sigma, 99.9%). The concentration of the stock solutions were determined by complexometric titration using standardized Na2H2EDTA solution in the presence of an appropriate end-point indicator (eriochromeblack-T for MgCl2, and ZnCl2, calconcarboxylic acid for CaCl2, murexide for CuCl2 and xylenol orange for YCl3, InCl3 and LnCl3 stock solutions).(12) The concentration of the ligand stock solution was determined by pH-potentiometry from the titration data obtained in the absence and in the presence of about 50-fold excess CaCl2.

The protonation constants of the ligand were calculated from the data obtained by titrating 2.5 mM and 4.4 mM ligand solutions (total 506 data pairs) with standardized KOH solution (0.1713 M) in the pH range of 1.8–11.9. The protonation constants of the ligand ( ) are defined as:

| (1) |

where i = 1, 2, …, 5 and [Hi−1L] and [H+] are the equilibrium concentrations of the ligand (i=1), protonated forms of the ligand (i=2, …, 5) and hydrogen ions, respectively.

In the systems containing Mg2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ or Cu2+, equilibrium in acidic media was reached rapidly enough to use a direct titration data for stability constant determinations. The titrations were carried out at 1:1 and 2:1 metal to ligand concentration ratio (CLig=2.5 mM). The data obtained at different concentration ratios were combined and fitted simultaneously. Even though the rate of complex formation of the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes is faster than that of the Ln(DOTA) complexes, they are not fast enough to determine the stability of the complexes by direct titration. Owing to the slow formation reactions of Y(NO2-Bn-PCTA) In(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes, the “out-of-cell” technique was applied for the stability constant determinations. The same method was used earlier to determine the stability constants of some Ln(PCTA) complexes and further details may be found elsewhere.(10, 13)

The program PSEQUAD was used to process the titration data (calculation of the protonation and stability constants).(14) The reliability of the protonation and stability constants are characterized by the calculated standard deviation values shown in parenthesis and fitting parameter values (ΔV – is the difference between the experimental and the calculated titration curves expressed in mL of the titrant) given in the footnotes of the tables.

Formation kinetics

The rates of complex formation of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) were studied at 25°C and 1.0 M KCl ionic strength using an Applied Photophysics RX.2000 rapid mixing accessory attached to a Cary 300 Bio UV-vis spectrophotometer. The formation reactions at low pH were sufficiently slow and were followed by conventional UV-vis spectroscopy. A typical concentration of PCTA was 0.2 mM while the concentration of NO2-Bn-PCTA was approximately 0.075 mM. The concentration of the metal ions was varied in the range 4–40 mM (20× to 200× metal excess) when the saturation curves were studied while it was set to 200-fold metal excess for the pH dependent measurements. Yb(PCTA) complex formation was studied in the pH range 3.59–5.16 while in the studies involving the NO2-Bn-PCTA ligand, the following pH ranges were used: pH = 3.93–5.69 for Ce3+ and Eu3+ and pH = 3.93–5.45 for Yb3+.

Both PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA contain a convenient built-in chromophore (pyridine unit) and both the formation and dissociation kinetics studies were performed by following the changes in the π → π* transition at 278 nm. At this wavelength the absorbance of the metal ions is either weak (Ce3+ and Eu3+) or zero (Y3+ and Yb3+). During the formation kinetic studies the non-coordinating buffers N-methylpiperazine (NMP, log K2H = 4.83) and dimethylpiperazine (DMP, logK2H = 4.18) were used to maintain the pH constant at a concentration of 0.05 M.(14)

Equation 2 was used to calculate the first order rate constants (kobs for formation and kd for dissociation), where A0, Ae and At are the absorbance values measured at the start of the reaction (t=0), at equilibrium and at time t, respectively. The data were fitted to Eqn 2 with the software Scientist® (Micromath) using a standard least-squares procedure.

| (2) |

The relative error for fitting of the absorbance vs. time data was less than 1% while the calculated first order rate constants, kobs and kp, were reproduced to within ±3% as determined in 12–15 identical experiments (each point on the curves reflects an average of 12–15 identical kinetic runs) for formation and 3 experiments for the dissociation reactions.

Kinetics of Dissociation

The acid catalyzed dissociation kinetics of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes were measured under pseudo-first-order conditions by mixing the appropriate complexes with a large excess hydrochloric acid (0.25–2.0 M) while keeping the ionic strength constant at 3.0 M with added KCl [(H++K+)Cl−]. A total of eight reactions was followed by direct spectrophotometry at 25°C until the conversion reached 80–100% in 0.075 mM complex solutions. Under these conditions changes of ~0.2 abs. units were detected throughout the dissociation reaction. In addition, the absorbance data, recorded as a function of time at 278 nm, showed no evidence of significant amplitude loss during the mixing of the components (usually 6–8 sec) and were fitted to Eqn. 2 as a single-exponential decay with excellent confidence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ligand design and synthesis

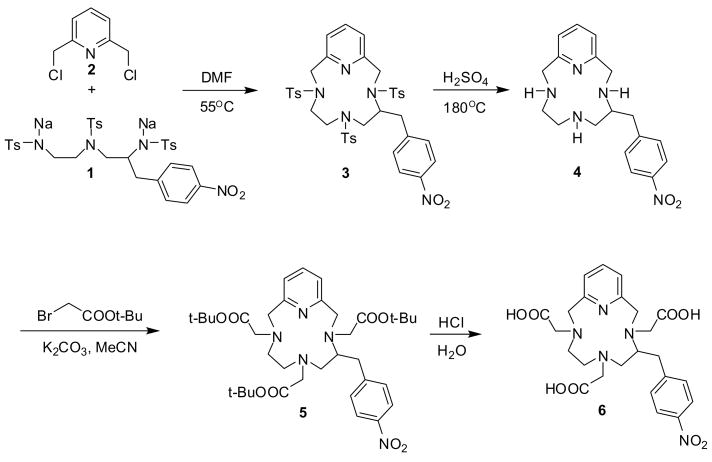

The aromatic isothiocyanato group is one of the most commonly used reactive functionalities for bioconjugation. It readily reacts with primary amino groups of peptides or proteins to form a stable thiourea linkage under mild conditions. The isothiocyanato functionality can easily be synthesized by reducing the corresponding nitro derivative and reacting the resulting aniline with thiophosgene. Both the aromatic isothiocyanato and amino compounds are sensitive to hydrolysis and oxidation, respectively, and have limited shelf-lifes so they are not suitable for extended equilibrium and kinetic measurements lasting several days (such as the “out-of-cell” technique). The nitro derivative, however, is stable at room temperature in aqueous solutions and can conveniently be used in these studies. Considering the parent ligand PCTA, the aromatic isothiocyanato function can be attached to three chemically distinct positions: one of the pyridine carbons, one of the acetate sidearms, or one of the carbon atoms of the ethylene bridges in the pyclen backbone. Each of these options has advantages and disadvantages. For example, functionalization of the pyridine moiety would be expected to have the least effect on the chelation properties of the ligand (the p-NO2-benzyl substituent does not have a strong inductive or mesomeric effect and so it is not expected to significantly alter the electron density on the pyridine N-atom) while side-arm functionalization may have an adverse effect on the metal binding ability of the acetate pendant arms. We have chosen the ethylene bridge for functionalization because our assumption was that this would eliminate any unwanted interference with the metal binding and the rigidifying effect of macrocyclic backbone substitution may actually add to the kinetic inertness of the resulting complexes. In addition, the backbone functionalized PCTA would structurally be analogous to the nitro precursor of the most frequently used bifunctional ligand, p-isothiocyanatobenzyl-DOTA, and so comparison of the equilibrium and kinetic properties of these two ligands could provide further insight into the design of new bifunctional chelators. The synthesis of the new bifunctional ligand, (S)-5-(p-nitrobenzyl)-PCTA (NO2-Bn-PCTA, 6) is outlined in Scheme 1. N, N′, N″-tritosyl (S)-2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine was prepared starting from L-nitrophenyl alanine following published procedures.(16) The key step of the synthesis is the Richman-Atkins type cyclization of the disodium salt of N, N′, N″-tritosyl-(S)-2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine (tosyl = p-toluenesulfonyl) 1 with 2,6-bis(chloromethyl)pyridine 2 in DMF giving about 55% yield of the tritosyl-nitrobenzyl-pyclen.(17) It is worth noting that the analogous cyclization reaction between the disodium salt of ditosyl-nitrobenzyl ethylenediamine and the tetratosyl derivative of N, N′-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-ethylenediamine failed to give the expected tetratosyl nitrobenzyl-cyclen due to side reactions involving the nitro group.(18) Interestingly, in this case, the aromatic nitro group did not affect the cyclization reaction, probably because the benzyl-halide type bis(chloromethyl)pyridine is a more reactive alkylating agent than the O-tosyl derivative of N, N′-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-ethylenediamine or diethanolamine. The tosyl groups of 3 were removed in concentrated sulfuric acid at 180 °C to afford (S)-5-(p-nitrobenzyl)-pyclen 4 in good yield. The 1H NMR spectrum of this cyclic tetramine is quite complicated as all the protons are magnetically nonequivalent and correct assignement could only be achieved with the help of 1H-1H COSY, 13C APT and 13C-1H HMQC NMR experiments (Figures S1-S3). Nitrobenzyl pyclen 4 was alkylated with tert-butyl bromoacetate in the presence of anhydrous potassium carbonate in acetonitrile to yield the tert-butyl ester 5. The tert-butyl ester groups were subsequently cleaved in aqueous hydrochloric acid to afford the ligand 6 as the HCl salt in about 35 % overall yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the bifunctional ligand, NO2-Bn-PCTA.

Protonation and stability constant determinations

The bifunctional ligand (S)-5-(p-nitrobenzyl)-PCTA has seven protonation sites and five protonation steps of these were detected in the pH range 1.8–11.8 when the ligand was titrated with strong base (KOH). The protonation constants obtained by pH-potentiometric measurements are presented in Table 1 along with the previously reported values for PCTA, DOTA and the bifunctional NO2-Bn-DOTA.

Table 1.

Protonation Constants of DO3A, PCTA, NO2-Bn-PCTA, DOTA and NO2-Bn-DOTA ligands (t = 25 °C).

| Ligand | DO3A | PCTA | NO2-Bn-PCTA | DOTA | NO2-Bn-DOTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0.1 M Me4NCla,b | 1.0 M KClc, 0.1 M Me4NNO3d | 1.0 M KCle | 0.1 M KNO3f, 0.1 M Me4NClg | 1.0 M Me4NClh |

| log K1H | 11.59a, 12.46b | 11.36c, 10.90d | 11.29 (0.01) | 12.09f, 12.60g | 10.93 |

| log K2H | 9.24a, 9.49b | 7.35c, 7.11d | 6.70 (0.02) | 9.76f, 9.70g | 9.14 |

| log K3H | 4.43a, 4.26b | 3.83c, 3.88d | 3.96 (0.03) | 4.56f, 4.50g | 4.44 |

| log K4H | 3.48a, 3.51b | 2.12c, 2.27d | 2.08 (0.04) | 4.09f, 4.14g | 4.14 |

| log K5H | –a, 1.97b | 1.29c, –d | 1.82 (0.03) | –f, 2.32g | 2.33 |

| Σlog KiH | 28.74a, 29.36b | 25.96c, 24.16d | 25.84 | 30.45f, 33.26g | 32.43 |

The first and the second protonation constants can be assigned to nitrogen atoms of the macrocyclic ring, while the next 3 protonation steps occur most likely at the acetate pendant arms. The first protonation constant of PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA are nearly identical but there is a noticeable difference in the second protonation constants (about 0.5 log K units). This was not unexpected as similar trend has been observed for the protonation constants of DOTA and p-NO2-Bn-DOTA. The somewhat smaller log K2 values found for the bifunctional versions is likely due to the conformational changes in the ethylene bridge of the macrocyclic ring induced by the p-nitrobenzyl substituent.(13) Interestingly, in the case of NO2-Bn-DOTA, both the first and the second protonation constants were affected while for NO2-Bn-PCTA only the second protonation constant is affected. This may be explained by the considerably less conformational flexibility of PCTA derivatives as compared to the DOTA-based ligands due to the rigidifying effect of the pyridine ring. Consequently, the extra strain introduced by the p-nitrobenzyl substituent will have a smaller effect on the pyclen macrocycle. Differences in the protonation sequence of NO2-Bn-PCTA and NO2-Bn-DOTA may also play a role. According to 1H-NMR studies, the most basic site in PCTA is the nitrogen atom opposite to the pyridine ring.(25) Addition of a second proton results in a rearrangement of the protonation sites to the two tertiary nitrogen atoms positioned trans- to each other and cis to the pyridine nitrogen.(25) In NO2-Bn-PCTA, the p-nitrobenzyl substituent is attached next to a tertiary nitrogen atom positioned cis to the pyridine nitrogen and the extra strain induced at this nitrogen atom reduces its basicity. The total basicity (Σlog KiH) of PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA is similar, around 25.8–25.9. Although this value is reasonably favorable, it is about 3 log K units lower than that of the DO3A and 6 to 7 log K units lower than that of the DOTA and NO2-Bn-DOTA. As a consequence, the thermodynamic stability constants for the complexes of PCTA-based ligands are expected to be somewhat lower than the corresponding DOTA-complexes.

The stability constants of the complexes of Mg2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions with NO2-Bn-PCTA were determined by pH-potentiometry in the presence of 1.0 M KCl as ionic background. The stability constants of these complexes along with the constants characterizing the stability of the M(DO3A), M(PCTA) and M(DOTA) complexes are listed in Table 2 (the stability constants of Mg2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ and Cu2+ complexes of NO2-Bn-DOTA have not been reported yet). The pH-potentiomeric titration data for both the 1:1 and 1:2 metal to ligand concentration ratios could be fitted well by assuming the formation of ML and MHL species only. The stability and protonation constants characterizing the formation of the Mg2+ and Ca(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes are in excellent agreement with data obtained for the Mg2+ and Ca(PCTA) complexes. Unlike the Cu2+ and Zn(PCTA) systems, no evidence of formation of ternary hydroxo complexes, MLH−1, was found in titrations with these same metal ions and NO2-Bn-PCTA, likely due to the higher stability of the latter complexes.

Table 2.

Stability constants of the complexes formed with Mg2+, Ca2+ Cu2+, and Zn2+ ions (I=1.0 M KCl, t=25 °C).

| M2+ | Equilibrium | PCTA | NO2-Bn-PCTA | DO3Ac | DOTAg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg2+ | [ML]/[M][L] | 11.82a, 12.35b | 12.39 (0.01) | 11.3d | 11.92 |

| [MHL]/[ML][H] | 3.70a, 3.82b | 3.52 (0.07) | – | 4.09 | |

| Ca2+ | [ML]/[M][L] | 12.38a, 12.72b | 12.72 (0.01) | 13.39, 11.74e | 17.23, 17.22e |

| [MHL]/[ML][H] | 3.66a, 3.79b | 3.66 (0.03) | – | 3.54 | |

| Cu2+ | [ML]/[M][L] | 17.79a, 18.79b | 19.11 (0.08) | 21.65, 22.87e | 22.25, 22.44e |

| [MHL]/[ML][H] | 4.03a, 3.58b | 3.67 (0.05) | 3.86, 3.2e,f | 3.78, 4.31e | |

| [ML]/[ML(OH)][H] | 10.3a, 11.28b | – | – | – | |

| Zn2+ | [ML]/[M][L] | 18.22a, 20.48b | 21.36 (0.11) | 21.87, 19.26e | 21.10h, 20.52e |

| [MHL]/[ML][H] | 3.64a, 3.10b | 3.02 (0.03) | 3.27f, 3.77e | 4.18h 4.35e | |

| [ML]/[ML(OH)][H] | 9.4a, 12.31b | – | 11.44e | – |

The data in Table 2 show that, unlike DOTA-based ligands, both PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA form more stable complexes with Zn2+ than with Cu2+. This observation is in accordance with the results reported earlier by Delgado et al. on the selectivity of some pyridine containing macrocyclic ligands for Zn2+ over Cu2+.(26) Interestingly, the selectivity was observed exclusively for the 12-membered PCTA ligand. (26) This unexpected selectivity is likely due to the rigid nature of the pyclen backbone and the slightly different type of interaction required (angle) between the pyridine nitrogen atom and Zn2+ and Cu2+ ions. This explanation is supported by the crystal structure of the [Cu(pyclen)Br]ClO4, which shows that the pyridine nitrogen — Cu2+ bond length is shorter than the secondary amine — Cu2+ bonds, while in the ([Zn(pyclen)Cl])2ZnCl4 complex the length of the pyridine-N — Zn2+ bond is comparable to that of the secondary amine-Zn2+ bonds.(26, 30)

The stability constants (log KML) of the complexes formed with some Ln3+, Y3+ and In3+ ions with NO2-Bn-PCTA were determined by “out-of-cell” potentiometric titration technique because of their slow formation rates. There was evidence for the formation of MHL species only for the larger metal ions (Ce3+ and Nd3+, log KCeLH=2.17 and log KNdLH=1.93, respectively) while ternary hydroxo complex formation was not considered. The stability constants of NO2-Bn-PCTA complexes with these trivalent ions are listed in Table 3 along with previously reported values for structurally related ligands.

Table 3.

Stability constants of ML type complexes formed with Y3+, In3+and some Ln3+ ions (I=1.0 M KCl, t=25 °C).

| M3+ | DO3Aa | PCTAd | NO2-Bn-PCTA | DOTAh | p-NO2-Bn-DOTAk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce3+ | 19.7 | 18.15 | 17.89 (0.12) | 23.39 | – |

| Nd3+ | – | 20.15 | 18.74 (0.04) | 22.99 | – |

| Eu3+ | 20.6b | 20.26, 20.9–21.1e | 19.02 (0.09) | 23.45 | – |

| Gd3+ | 21.0 | 20.39, 21.0f | 19.42 (0.07) | 24.0i, 24.67, 25.3j | 24.2 |

| Ho3+ | – | 20.24 | 19.66 (0.06) | 24.54 | – |

| Yb3+ | – | 20.63 | – | 25.00 | – |

| Lu3+ | 23.0 | – | 19.85 (0.09) | 25.41 | 24.9 |

| Y3+ | 21.1c | 20.28 | 18.78 (0.09) | 24.9j | 24.5 |

| In3+ | – | 21.42g 24.7 (0.1) | 23.91 (0.09) | 23.9i | – |

As expected, the stability of the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes increases substantially from Ce3+ to Eu3+ then increases only gradually with decreasing ion size, maximizing at Lu3+. This trend is similar to that seen previously for complexes of macrocyclic ligands with a similar size and number of donor atoms (Ln(PCTA), Ln(DO3A), Ln(DOTA)).(10, 31, 32, 35, 36) Despite the similar basicities of PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA, the stability of the Ln(III) complexes formed with the bifunctional ligand are about 0.5–1 log K units lower than those of the parent ligand, PCTA. Since the basicities of these ligands are similar, this difference is likely due to the steric effect of the p-nitrobenzyl substituent. Although the thermodynamic stabilities of lanthanide complexes of NO2-Bn-PCTA are somewhat lower than stability of the corresponding DOTA complexes, they remain reasonably favorable for potential in vivo applications.(37)

It is of interest to note that In3+ forms quite stable complexes with both PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA (the log KML value is comparable to the value published for In(DOTA). However, for a more meaningful comparison, the available literature data on In3+-ligand stability constants should be analyzed carefully because these are often measured in the presence of Cl− containing electrolytes (e.g. KCl, NaCl and Me4NCl) used to maintain the constant ionic strength during titrations. However, Cl− ions can form relatively stable complexes with In3+ ion with log β1, log β2 and log β3 values of 2.58, 3.84 and 4.20, respectively (25 °C, I = 3.0 M NaClO4).(38) If the formation of InClx(3−x)+ species is not taken into account, then the resulting stability constants only represent the lower limits of stability and the actual stability constants are somewhat higher (with about 4 log K units). This appears to be the case for In(DOTA), as its stability was measured in the presence of 0.1M KCl and the formation of InClx(3−x)+ species was ignored by Clarke et al.(36), whereas it was accounted for in the calculated stabilities of In(PCTA) and In(NO2-Bn-PCTA) here. In the pH range 1.5–2.5, the conditional stabilities of the In(PCTA) and In(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes are relatively low and the Cl− ions can compete well with these ligands. Under the conditions employed in our study (I=1.0 M KCl) only the complexes InCl2−, InCl3 and In(PCTA) are present in the equilibrium (there is no free In3+) and the stability of In-complexes listed in Table 3 were calculated with the use of the known log βX values. It is worth noting that the stability of In(PCTA) published by Delgado et al. is 3.3 log K units lower than that measured here (Table 3).(26) The competitive Cl− complex formation cannot explain the discrepancy in this case since Delgado et al. used MeN4NO3 to set the ionic strength of the samples.(26) It is more likely that these differences originate from differences in the protonation constants of the ligand due to the different methods used to evaluate these constants.

Kinetics of Complex Formation

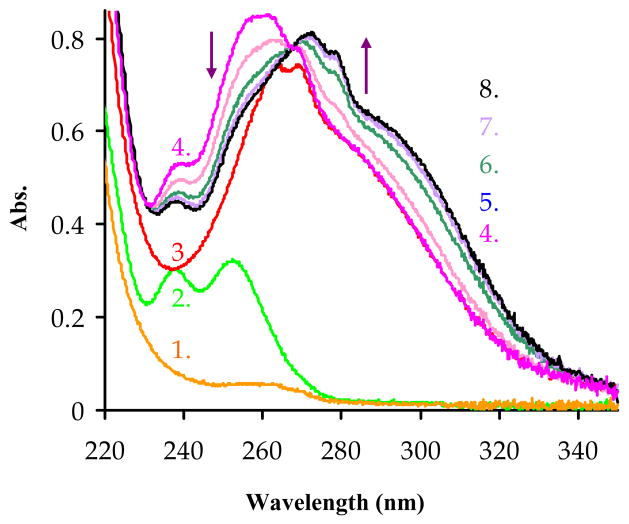

The formation kinetics of the complexes involving macrocyclic ligands are usually considerably slower than the corresponding complexes formed with multidentate, open-chain ligands.(39) Unlike the polycarboxylate ligands derived from linear polyamines, the corresponding polycarboxylate macrocyclic ligands tend to form relatively stable protonated “out-of-cage” complexes as intermediates which then rearrange slowly to the thermodynamically stable complex in a general base-catalyzed step.(40–42) Mono-, di- and occasionally triprotonated intermediates have been demonstrated by different spectroscopic techniques (UV-vis, luminescence, NMR, EXAFS etc).(43–53) The formation kinetics of Ln(III) complexes are most easily studied by UV-vis spectroscopy (Ce3+ and Eu3+) or relaxivity measurements (Gd3+).(43, 46–49) Complexation of the smaller ionic radii Ln(III) ions that have no absorption in the UV-vis (Yb3+ or Lu3+) can be followed indirectly by UV-vis spectroscopy using an appropriate acid-base indicator to register slight pH changes during the course of the reaction.(43, 46, 54) Fortunately, PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA have a convenient built-in chromophore arising from the π → π* transition of the pyridine moiety (εmax= 1.25×104 dm3mol−1cm−1, λmax= 269 nm, pH=3.97, for NO2-Bn-PCTA) that undergoes a bathochromic shift upon metal ion encapsulation (λmax= 278 nm) (Figure 3). As the bathochromic shift and the molar extinction coefficient are almost independent of which metal ion is encapsulated, this transition can be used to monitor complex formation for a large variety of metal ions. Here, formation kinetics were examined for three lanthanide ions, one of larger ionic radius (Ce3+ -103 pm), one of medium ionic radius (Eu3+ – 95 pm) and one of smaller ionic radius (Yb3+ – 86 pm) to compare the effect of metal ion size on the rates of complex formation.

Figure 3.

Absorbance changes in UV region during the formation of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA) after mixing Ce3+ and the ligand at 10:1 metal to ligand concentration ratio at pH=4.20 (in 0.04 M DMP, I=1.0 M KCl and CLig=6×10−5 M), the curves represent the UV-spectrum of 1) 40 mM buffer, 2) 6×10−4 M CeCl3 in DMP buffer, 3) 6×10−5 M ligand in DMP buffer, 4) immediately after mixing the Ce3+ with the ligand (“0” min), 5) after 2 min, 6) after 7 min, 7) after 12 min and 8) after 70 min (equilibrium).

The formation kinetics of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (Ln = Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb3+) were studied at different pH and metal ion concentrations (20 to 200-fold metal excess) under pseudo-first-order conditions. In the presence of excess Ln3+, the rate of complex formation may be described as:

| (3) |

where [L]t is the total concentration of the NO2-Bn-PCTA (complexed and uncomplexed forms) and kobs is a pseudo-first-order rate constant. Plots of kobs versus Ln3+ ion concentraton showed saturation kinetics at high Ln3+ concentration. The shape of these plots is characteristic of rapid formation of an intermediate that rearranges slowly to the final product in a slow, rate determining step. A similar mechanism has been reported for other Ln(III) complexes formed with macrocyclic polyaminopolycarboxylic acid ligands including Ln(NOTA), Ln(DOTA)−, Ln(TRITA)− and Ln(PCTA).(10, 43, 46, 49) The intermediate formed along the pathway to stable LnDOTA and LnPCTA complexes has been shown to be a diprotonated species while intermediate formed in the LnNOTA and LnDETA complexes is monoprotonated.(46, 55) In each case, the number of protons in the intermediate reflects the basicity of the macrocyclic nitrogen donor atoms in these systems. Tetraazamacrocycles generally have two very basic nitrogen atoms while triaza macrocycles typically have one basic and one moderately basic nitrogen,(56) the difference between the 1st and 2nd protonation constants (log K1H − log K2H) is generally larger for triaza macrocycles (4.74–6.31 for NOTA) than for tetraaza-macrocyclic ligands (log K1H − log K2H = 2.33–2.90 for DOTA (the range of the protonation constant differences reflect the literature data reported for the given ligand). The difference between the 1st and 2nd protonation constants of NO2-Bn-PCTA (4.59) is somewhat greater than the same difference in PCTA (3.99) and lies between the corresponding differences for DOTA, NO2-Bn-DOTA and NOTA. This comparison suggests that the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) intermediates will likely also be diprotonated. This was verified experimentally for the Yb3+ complex in weakly buffered solutions by a UV-vis spectroscopic method described earlier.(43, 46, 54) Changes in the absorbance of a sample containing an acid-base indicator (methyl orange) in weakly buffered solutions (0.01M DMP) were calibrated by the addition of a known amount of strong acid stock solution. Using this calibration curve the concentration (number of moles) of protons released immediately after mixing of the two components (ligand and metal-ion solution) and at the end of the complexation reaction was determined and compared. The components (ligand and metal ion solutions) were mixed at pH 3.95, a slight pH change was registered upon mixing followed by a more pronounced change in pH during the approach to equilibrium (~6 hours). From the volume of acid needed to return the pH to its original value, it was estimated that about 4 times more protons were released in the slow process than in the fast one. Since the ligand exists as H2.5L at pH ~4, the release of 0.5 eq. of H+ upon mixing followed by the liberation of 2 eq. of H+ after reaching equilibrium is consistent with formation of a diprotonated intermediate in Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA).

Since no major differences in the mechanism of complex formation of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and Ln(PCTA) complexes could be detected, the raw data measured for the formation of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes were treated the same way as the Ln(PCTA) complexes, the details of which will not be repeated here.(10) Briefly, the pseudo-first-order rate constants obtained at various pH and metal concentrations were fitted to Eqn. (4) (additional information can be found in electronic supporting information) and the kr rate constants and the stability constants of the intermediates, KLn(H2L)* were calculated as described for the Ln(PCTA) complexes.

| (4) |

The stability constants of the Ce3+ and Eu(H2NO2-Bn-PCTA) intermediates determined from the kinetics data were 2.83 ± 0.16 and 2.90 ± 0.11, respectively. The stability of the Yb(H2PCTA) was also redetermined in the present study and found to be in excellent agreement with our previously published value (2.70 ± 0.08). The stability constants of the intermediates calculated from the kinetic data are lower than those obtained from pH-potentiometric titration for the Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb(H2DOTA)+ complexes (log K = 4.5, 4.3 and 4.2 respectively), consistent with differences in the structures expected for these intermediates. The nature of this intermediate has been thoroughly investigated for DOTA. Recent pH-potentiometry, luminescence and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXASF) spectroscopy studies have indicated that the formation of Ln(DOTA) chelates actually involves two diprotonated intermediates, (51, 52) the first of which is formed instantaneously where the central Ln3+ ion is coordinated to oxygens of each of the four carboxylate groups and five water molecules (q = 5). This intermediate rapidly converts into the more stable diprotonated species in which the metal ion is coordinated to four oxygens of the acetate sidearms, two N-atoms of the macrocyclic ring and three water molecules (q = 3). The stability of the more stable (q = 3) intermediate has been determined by both pH-potentiometry and spectrophotometry (log K = 4.5, 4.3, and 4.2 for Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb3+, respectively, by pH-potentiometry).(43) For ligands with three acetate sidearms (PCTA, DO3A) the stability of the intermediate is expected to be lower. (57) There are no stability data available for the intermediates in Ln(DO3A) systems but q was found to be 4.6 for the Eu(DO3A) complex.(52) Data published for [10-[2,3-dihydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)propyl]-DO3A (DO3A-butriol) (log K = 2.4, 2.5, and 2.43 for the Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb3+ intermediates, respectively) suggest that only the acetate oxygens coordinate.(57) Considering the Eu3+ aqua ion as nine-coordinate, one can assume that the PCTA and NO2-Bn-PCTA ligands also coordinate to the metal by the three acetate oxygen donor atoms. This assumption is supported by the fact that the stability of the intermediates are higher than the stability of the monoacetate complexes and are very similar to the stability of Ln-dicarboxylic acid complexes.(15)

It is now generally accepted that the mechanism of complex formation for DOTA and DOTA-like ligands involves the rearrangement of the diprotonated intermediates through rapid deprotonation of the intermediate to a monoprotonated species in a fast equilibrium step. This is followed by the release of the second proton in a slow, rate determining step and the rapid structural rearrangement of the fully non-protonated complex to the final product. In accordance with this mechanism, the validity of general base catalysis has been confirmed in some cases.(10, 24, 57)

Eqn. (4) can further be simplified if the experimental conditions are chosen so that the conditional stability constant of the intermediate will be high (KCLn(H2L)* = KLn(H2L)*/αH2L) and the reaction will be pseudo-first-order (CLn ≥ 10CL). Under these conditions KCLn(H2L)* × [Ln]tot ≫ 1 and thus 1 can be neglected in the denominator of Eqn. 4. This simplifies Eqn. 4 to kobs ≈ kr, (kr is the “saturation value” of the rate constant kobs when the formation of the intermediate is complete). In other words, the kr values can be approximated with kobs if a large excess of Ln3+ is used over the ligand. The necessary excess of the Ln3+ to reach the kobs ≈ kr condition can be determined from the expression of stability constant of the accumulated intermediate (Eqn. 5):

| (5) |

To ensure quantitative formation of the intermediate, the ratio [Ln(H2L)*]/[H2L] ([bound]/[unbound]) in Eqn. 5 should be ≫ 1. The ratio [bound]/[unbound] will be equal to 1 when the ratio [Ln3+]/[H2L] = 19 (as calculated from the stability constant of the intermediate), so for a more detailed pH dependence study, the ratio [Ln3+]/[H2L] was set to 200.

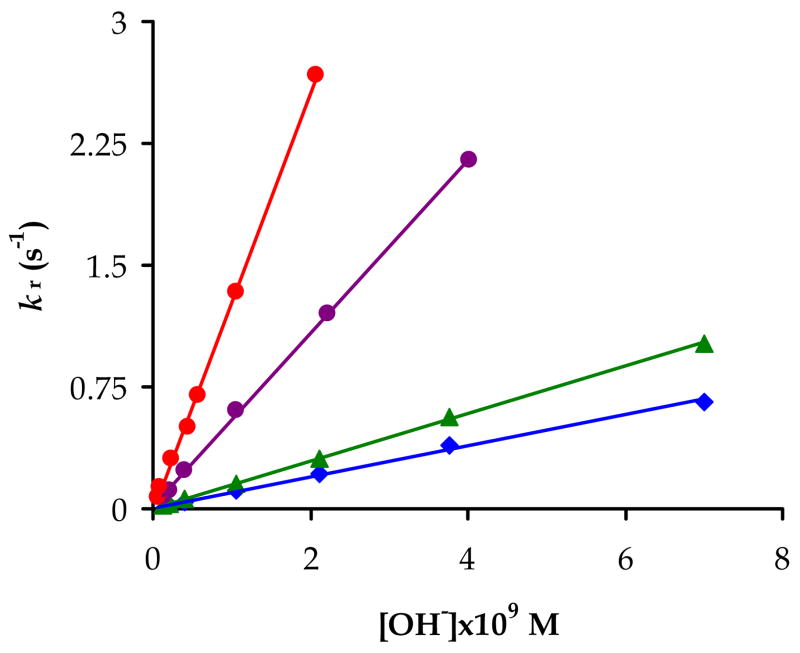

The rate constants kr obtained under these conditions were found to be inversely proportional to the H+ ion concentration (Eqn. 6) for all the metal ions and ligands studied in the present work (Figure 4). The kOH values were obtained from the fitting of kr values gained at different pH values to Equation 6 (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Formation rates of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (blue diamonds), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (green triangles), Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (purple circles) and Yb(PCTA) (red circles) vs. OH− ion concentration (I=1.0 M KCl, t=25 °C).

Table 4.

Rate constants, kOH, characterizing rearrangement of the intermediates in Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA), and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (I=1.0 M KCl, 25 °C).

| (6) |

The rate of complex formation (rearrangement of the intermediates) increases with decreasing lanthanide-ion size. This decreasing tendency of the kOH values along the lanthanide series is not surprising since it has been reported for numerous cyclen derivatives with acetate pendant arms, and can be explained by the higher charge density of the heavier lanthanides (the OH− ion catalyzed deprotonation is faster for the metal ions with greater positive charge density).(42) The Ln(NOTA) complexes do not follow this trend and for some DOTA-tetra(amides) the opposite order of formation constants was recently reported.(46, 61, 62) For the latter complexes, the extremely slow water exchange that is typical of DOTA-tetraamide systems seems to be responsible for this unusual behaviour across the lanthanide series.(61, 62)

Kinetics of Dissociation

The kinetic inertness of a complex will largely determine its fate in vivo. (63) Even if the thermodynamic stability of the complex is not very high, it is possible that it can safely be used for biomedical applications if the complex does not dissociate in vivo. The usefulness of acid catalyzed dissociation rates in predicting the fate of a complex in vivo was first noted by Wedeking when it was found that the extent of long term Gd-deposition in the whole body, liver and femur of mice was correlated well with the ex vivo acid catalyzed dissociation rates of various open chain and macrocyclic 153Gd-labeled complexes. (64) The deposition of Gd was the lowest for Gd(DOTA) and this is in good agreement with its extremely slow proton assisted dissociation rate. (64) Generally, Ln(III) complexes of DOTA-like ligands is very slow under physiological conditions (63), probably due to their tightly packed and highly rigid structure. (45) Later it was realized that the in vivo dissociation mechanism of acyclic and macrocyclic lanthanide complexes is quite different. The dominant pathway for in vivo dissociation of Ln-chelates of DOTA-like ligands involves the acid catalyzed dissociation and the acid independent spontaneous dissociation. On the other hand, Ln-complexes of open chain ligands (EDTA, DTPA) dissociate in vivo through metal ion [Zn(II), Cu(II)] catalyzed pathway, which is acid-independent above pH 4.5. (63) Therefore, the in vitro dissociation kinetic studies of macrocyclic chelates are focused on the acid catalyzed dissociation and from the kinetic data the k1 and k2 rate constants corresponding to acid-assisted dissociation of the mono and diprotonated complexes as well as the k0 rate constant that describes the acid-independent spontaneous dissociation can be estimated. (43, 45) Since at pH > 2, Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes dissociate too slowly to collect kinetic data over a reasonable period of time, the acid catalyzed dissociation of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes was examined at pH ≪ 2, where the complexes are thermodynamically unstable. Under these experimental conditions, proton-assisted dissociation follows first-order kinetics with respect to the complex ([H+]≫[Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA)]) and the rate of the dissociation is directly proportional to the total concentration of the complex:

| (7) |

where kd is a pseudo-first-order rate constant. Under the conditions employed in the current work (0.25 M HCl < C < 2.00 M HCl), complex dissociation proceeds via some combination of acid-assisted and spontaneous dissociation and consequently the total concentration of the complex will be a sum of equilibrium concentrations of the complex ([LnL]) and its different protonated forms ([LnHxL] where x= 1, 2, …)

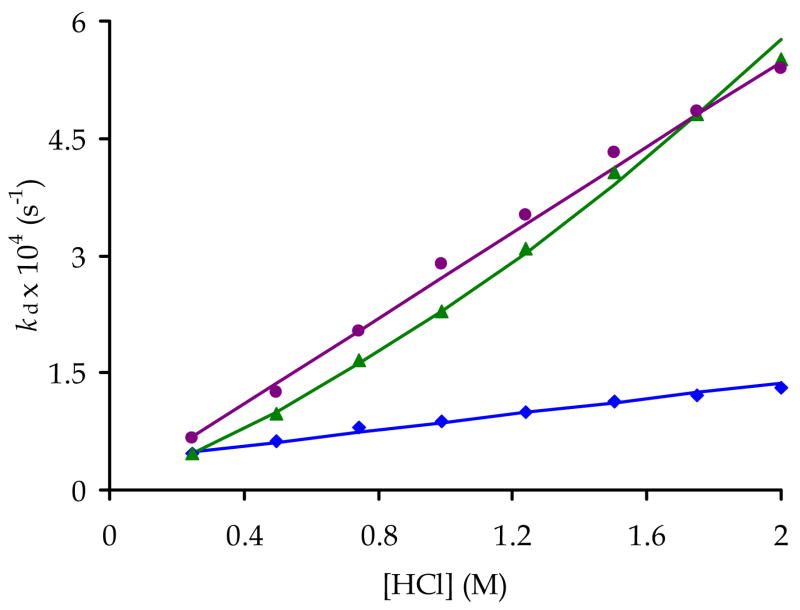

The dependence of the pseudo-first order dissociation rate constants (kd) on the H+ ion-concentration was measured for Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (Figure 5, each point on this figure is an average of two identical kinetic runs). These data demonstrate that the rate of dissociation of the complexes is either proportional to the acid concentration (Ce and Yb) or shows a second-order dependence and can be described by Eqns. 8 and 9, respectively:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where k0 is a constant that describes the acid-independent dissociation (spontaneous dissociation) while k1 and k2 corresponds to acid-assisted dissociation of the protonated complexes. Ln3+ complexes of the parent PCTA behaved slightly differently, since Eu(PCTA) and Yb(PCTA) exhibited linear dependence at low acid concentrations while saturation type dependence was observed for Ce(PCTA), Y(PCTA) and Yb(PCTA) at higher acid concentration. This is likely a consequence of the lower thermodynamic stability of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes. As a result, the mono- and diprotonated intermediates are also expected to have lower stability and the dissociation curves reach “saturation” at higher acidity beyond the range of acid concentration used in the study.

Figure 5.

Dependence of the dissociation rate constants (kd) on the H+ ion concentration in the dissociation of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (blue diamonds), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (green triangles), Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (purple circles) complexes at 25°C.

The acid catalyzed dissociation of NO2-Bn-PCTA complexes very likely follows the same mechanism that accounts for the dissociation of DOTA complexes, with protonation of a carboxylate oxygen as the initial step. The protonated species then undergoes rearrangement while the proton is transferred from the acetate arm to a ring nitrogen atom. Electrostatic repulsion between the protonated nitrogen and the central metal ion in the macrocyclic cavity of ligand causes the formation of an “out-of-basket” complex which may then dissociate directly or can simultaneously follow a pathway that involves an attack by a second proton. Proton transfer and rearrangement of the complex occurs concurrently and either of these processes can be the rate limiting step. The rigidity of the macrocyclic ligand is responsible for the high kinetic inertness of these complexes.

In the physiologically relevant pH range the contribution of the spontaneous dissociation of the complex, characterized by the k0 rate constant, may be significant. The value of k0 can be estimated from the kinetic data (Eqns. 8) but normally its value is zero within the experimental error because under the experimental conditions (pH ≪ 2) the contribution of the spontaneous dissociation to the dissociation process is very small. In our studies fitting of dissociation kinetics data for the Eu3+ and Yb3+ complexes returned a small and negative value for k0. Similar conclusions were reached by other researchers who determined the rate constant characterizing the spontaneous dissociation of Gd(DOTA) from the kinetic data and the contribution of the acid-independent dissociation was neglected. (43, 45) We have found a positive k0 = (4.0±0.3)×10−5 s−1 with acceptable uncertainty for Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA). However, this value appears to be too high for spontaneous dissociation of this type of complexes. As reported earlier,(10) the rate of spontaneous dissociation can be predicted from acid-catalyzed dissociation rate data. By comparing data obtained for complexes of macrocyclic ligands of similar ring size, number and quality of donor atoms it was found that the rate of spontaneous dissociation is usually 4–6 orders of magnitude lower than the acid catalyzed dissociation rate constant, k1.(10) This approximation gives about 10−8 to 10−9 s−1 as the lower limit of the rate constant characterizing spontaneous dissociation of the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes. In order to determine the k0 value more precisely, the measurements must be performed at a pH range closer to 7. Preliminary data collected for Gd(PCTA) and Gd(NO2-Bn-PCTA) in the pH range of 3.0–6.0 and in the presence of Zn2+ as scavenger metal ion indicate that a estimate for k0 is about 10−8 to 10−9 s−1. Moreover, a recent study on the transmetallation of Gd(PCTA) and its rigidified derivative, Gd(CHX-PCTA) as well as other cyclen based macrocyclic Gd(III) complexes in the presence of Zn2+ ions and at physiological pH showed no measureable dissociation of the complexes over the time period of 9000 minutes.(37, 65)

The acid-catalyzed dissociation rate constants for some Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes are listed and compared to those of other macrocyclic complexes in Table 5. Interestingly, when compared to the parent ligand, PCTA, the introduction of the p-nitrobenzyl substituent did not affect adversely the kinetic inertness of the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes. Even though the thermodynamic stability of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) is slightly lower than the corresponding PCTA complexes, their kinetic inertness towards acid catalyzed dissociation is somewhat higher. This is likely due to the rigidifying effect of the p-nitrobenzyl subtituent attached to the pyclen backbone. A similar trend was observed for open-chain and macrocylic ligands when their structures were rigidified. For example, the half-life of Gd(cyclohexyl DOTA) in 1M HCl is 50 h compared to 23 h of Gd(DOTA).(67) The improvement in kinetic inertness is the most pronounced for the Ce3+ complex where the rate constant k1 was found to be at least an order of magnitude lower than it is for the Ce(PCTA). Furthermore, Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA) was found to be even more inert towards acid-assisted dissociation than Ce(DOTA).

Table 5.

Comparison of acid-assisted dissociation rate constants (k1, M-1s-1) for Ce3+, Eu3+ and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes (t=25 °C and I =1.0 M KCl). Data for some other complexes formed with macrocyclic ligands are also listed for comparison.

| Ce3+ | Gd3+ | Yb3+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DO3Aa | 1.12×10−1 | 2.7×10−2, 1.17×10−2b 5.2×10−2c |

2.8×10−2 |

| PCTAd | 9.6×10−4f | 5.1×10−4e 1.1×10−3c,f |

3.9×10−4 2.8×10−4f |

| NO2-Bn-PCTA | (4.77±0.22)×10−5 | (1.75±0.06)×10−4g | (2.78±0.03)×10−4 |

| DOTAh | 8×10−4i | 2.0×10−5j, 8.4×10−6k, 1.4×10−5l | – |

calculated form “saturation kinetics” from reference (32),

reference (66),

data corresponds to YL complex,

reference (10),

data corresponds to EuL complex,

calculated form “saturation kinetics” obtained in a wide concentration range,

second-order dependence on H+ ion concentration with third-order rate constant (5.7±0.4)×10−5 M−2s−1 was also observed,

reference (47),

second-order dependence on H+ ion concentration with third-order rate constant 2.0 ×10−3 M−2s−1 was also observed (47),

t= 37 °C reference (43),

reference (45),

data corresponds to EuL (43).

CONCLUSIONS

The novel bifunctional ligand p-nitrobenzyl-PCTA was synthesized in reasonable yields. The total basicity of p-nitrobenzyl-PCTA was very similar to that of PCTA and about 6 orders of magnitude less than the basicity of DOTA. As expected, the stability of the complexes of M(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (M = Mg2+, Ca2+, Cu2+, Zn2+) is very similar to that of the corresponding PCTA complexes. The stability of the Ln complexes of this new bifunctional ligand is slightly lower (Δlog K = 0.5–1.0), than that of the parent ligand but the trend of the stability constants across the Ln3+ series remains unaffected. The stabilities of In(PCTA) and In(NO2-Bn-PCTA) were found to be quite high (log K~24), about 3.3 log K units higher than previously reported for In(PCTA). This difference is a consequence of competitive complex formation between the Cl− and In3+. As expected, the formation of Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes proceeds through a diprotonated intermediate and the rate constant characterizing the OH− ion catalyzed deprotonation and rearrangement of the intermediate was found to be comparable to that of PCTA complexes. The kinetic inertness of selected Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) (Ln = Ce, Eu Yb) complexes was studied by measuring the rate constant characterizing the acid-catalyzed dissociation and was found to be higher than the corresponding PCTA chelates probably due to the rigidifying effect of the p-nitrobenzyl substituent. In summary, structural modification of the pyclen backbone with a p-nitrobenzyl substiuent does not have an unfavorable influence on either the thermodynamic or kinetic properties of PCTA. The bifunctional ligand forms complexes about an order of magnitude faster than DOTA while the kinetic inertness of the Ln(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes are comparable to that of DOTA chelates. The rapid complex formation kinetics combined with satisfactory thermodynamic stability and excellent kinetic inertness of the complexes renders this bifunctional ligand particularly suitable for nuclear medicine applications when rapid complex formation is required under mild conditions. In addition, the pyridine moiety is a good sensitizer for luminescent lanthanides such as Eu(III) and Tb(III) and using time gating imaging techniques the lanthanide emission can be easily separated from the background tissue fluorescence because of the much longer luminescent lifetime (milliseconds) of these ions. (68) Thus, p-nitrobenzyl-PCTA could also be used in the design and construction of in vivo bimodal (nuclear/optical or MRI/optical) imaging probes. (69, 70)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to Dr Róbert Király (University of Debrecen, Hungary) on the occasion of his retirement. The authors are grateful to Professor Lynn A Melton (University of Texas at Dallas) for the access to the RX.2000 Rapid Mixing Accessory. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA-115531, RR-02584 & EB-004582), the Robert A. Welch Foundation (AT-584), the EMIL Project funded by the EC FP6 Framework Program (LSCH-2004-503569) and the Hungarian Science Foundation (OTKA K-69098).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Detailed synthesis of the ligand, 1H-1H COSY, 13C APT and 13C-1H HMQC NMR spectra of nitrobenzyl pyclen, evaluation of kinetic data, the rate constants characterizing the rearrangement of the intermediates to the final products in formation reactions of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes, the kp values for dissociation of Ce(NO2-Bn-PCTA), Eu(NO2-Bn-PCTA) and Yb(NO2-Bn-PCTA) complexes. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Boswell CA, Brechbiel MW. Development of radioimmunotherapeutic and diagnostic antibodies: an inside-out view. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:757–778. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassis AI. Therapeutic radionuclides: biophysical and radiobiologic principles. Semin Nucl Med. 2008;38:358–366. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Kovacs Z. The synthesis and chelation chemistry of DOTA-peptide conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:391–402. doi: 10.1021/bc700328s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong HS, Ma X, Le T, Kwamena B, Milenic DE, Brady ED, Song HA, Brechbiel MW. Rational design and generation of a bimodal bifunctional ligand for antibody - targeted radiation cancer therapy. J Med Chem. 2008;51:118–125. doi: 10.1021/jm070401q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breeman WAP, de Blois E, Bakker WH, Krenning EP. Radionuclide peptide cancer therapy. In: Chinol M, Paganelli G, editors. Radionuclide Peptide Cancer Therapy. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2006. pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camera L, Kinuya S, Garmestani K, Wu C, Brechbiel MW, Pai LH, McMurry TJ, Gansow OA, Pastan I, Paik CH. Evaluation of the serum stability and in vivo biodistribution of CHX-DTPA and other ligands for yttrium labeling of monoclonal antibodies. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:882–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong HS, Garmestani K, Ma DS, Milenic DE, Overstreet T, Brechbiel MW. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel macrocyclic ligands with pendent donor groups as potential yttrium chelators for radioimmunotherapy with improved complex formation kinetics. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3458–3464. doi: 10.1021/jm0200759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong HS, Song HA, Ma X, Milenic DE, Brady ED, Lim S, Lee H, Baidoo K, Cheng D, Brechbiel MW. Novel bimodal bifunctional ligands for radioimmunotherapy and targeted MRI. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1439–1447. doi: 10.1021/bc800050x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aime S, Calabi L, Cavallotti C, Gianolio E, Giovenzana GB, Losi P, Maiocchi A, Palmisano G, Sisti M. [Gd-AAZTA](−): A new structural entry for an improved generation of MRI contrast agents. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7588–7590. doi: 10.1021/ic0489692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tircso G, Kovacs Z, Sherry AD. Equilibrium and formation/dissociation kinetics of some Ln(III)PCTA complexes. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9269–9280. doi: 10.1021/ic0608750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irving HM, Miles MG, Pettit LD. A study of some problems in determining stoicheiometric proton dissociation constants of complexes by potentiometric titrations using a glass electrode. Anal Chim Acta. 1967;38:475–488. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarzenbach G, Flaschka H. Complexometric Titrations. Barnes and Noble; New York: 1969. Complexometric titrations; p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods M, Kovacs Z, Kiraly R, Brucher E, Zhang SR, Sherry AD. Solution dynamics and stability of lanthanide(III) (S)-2-(p-nitrobenzyl)DOTA complexes. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:2845–2851. doi: 10.1021/ic0353007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zekany L, Nagypal I. Computational methods for the determination of formation constants. In: Leggett DJ, editor. Computational Methods for the Determination of Formation Constants. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martell AE, Smith RM, Motekaitis RJ. Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes, Database Version 8.0. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansari MH, Ahmad M, Dicke KA. Synthesis of 2-(p-aminobenzyl) derivatives of 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N, N′, N″-triacetic acid (NOTA) and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N, N′, N″, N‴-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) - macrocyclic bifunctional chelating-agents useful for antibodies labeling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1993;3:1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richman JE, Atkins TJ. Nitrogen analogs of crown ethers. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:2268–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMurry TJ, Brechbiel M, Kumar K, Gansow OA. Convenient synthesis of bifunctional tetraaza macrocycles. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3:108–117. doi: 10.1021/bc00014a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar K, Chang CA, Francesconi LC, Dischino DD, Malley MF, Gougoutas JZ, Tweedle MF. Synthesis, stability, and structure of gadolinium(III) and yttrium(III) macrocyclic poly(amino carboxylates) Inorg Chem. 1994;33:3567–3575. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi A, Calabi L, Giorgi C, Losi P, Mariani P, Paoli P, Rossi P, Valtancoli B, Virtuani M. Thermodynamic and structural properties of Gd3+ complexes with functionalized macrocyclic ligands based upon 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 2000:697–705. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siaugue JM, Favre-Reguillon A, Dioury F, Plancque G, Foos J, Madic C, Moulin C, Guy A. Effect of mixed pendant groups on the solution properties of 12-membered azapyridinomacrocycles: evaluation of the protonation constants and the stability constants of the europium(III) complexes. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2003:2834–2838. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siaugue JM, Segat-Dioury F, Favre-Reguillon A, Wintgens V, Madic C, Foos J, Guy A. Europium(III) complex formed with pyridine containing azamacrocyclic triacetate ligand: characterization by sensitized Eu(III) luminescence. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2003;156:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaves S, Delgado R, Dasilva JJRF. The stability of the metal-complexes of cyclic tetra-aza tetraacetic acids. Talanta. 1992;39:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(92)80028-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burai L, Fabian I, Kiraly R, Szilagyi E, Brucher E. Equilibrium and kinetic studies on the formation of the lanthanide(III) complexes, [Ce(dota)](−) and [Yb(dota)](−) (H(4)dota=1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1998:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aime S, Botta M, Crich SG, Giovenzana GB, Jommi G, Pagliarin R, Sisti M. Synthesis and NMR studies of three pyridine-containing triaza macrocyclic triacetate ligands and their complexes with lanthanide ions. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:2992–3000. doi: 10.1021/ic960794b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delgado R, Quintino S, Teixeira M, Zhang A. Metal complexes of a 12-membered tetraaza macrocycle containing pyridine and N-carboxymethyl groups. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang CA. Selectivity of macrocyclic aminocarboxylates for alkaline-earth metal ions and stability of their complexes. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1996:2347–2350. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar K, Tweedle MF, Malley MF, Gougoutas JZ. Synthesis, stability, and crystal structure studies of some Ca2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ complexes of macrocyclic polyamino carboxylates. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:6472–6480. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delgado R, Dasilva JJRF. metal-complexes of cyclic tetra-azatetra-acetic acids. Talanta. 1982;29:815–822. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(82)80251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alcock NW, Busch DH, Liu CY. Bis(hloro-(3,6,9,15-tetra-azabicyclo(9.3.1)pentadeca-1(15),11,13-triene)-zinc) tetrachlorozincate. CCDC 628572, Identifier: LESSEI 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar K, Tweedle MF. Macrocyclic polyaminocarboxylate complexes of lanthanides as magnetic-resonance-imaging contrast agents. Pure Appl Chem. 1993;65:515–520. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar K, Chang CA, Tweedle MF. Equilibrium and kinetic-studies of lanthanide complexes of macrocyclic polyamino carboxylates. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:587–593. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu SL, Horrocks WD. General method for the determination of stability constants of lanthanide ion chelates by ligand ligand competition: laser-excited Eu3+ luminescence excitation spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 1996;68:394–401. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu SL, Horrocks WD. Direct determination of stability constants of lanthanide ion chelates by laser-excited europium(III) luminescence spectroscopy: application to cyclic and acyclic aminocarboxylate complexes. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1997:1497–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cacheris WP, Nickle SK, Sherry AD. Thermodynamic study of lanthanide complexes of 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N, N′, N″-triacetic acid and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N, N′, N″, N‴-tetraacetic acid. Inorg Chem. 1987;26:958–960. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke ET, Martell AE. Stabilities of trivalent metal-ion complexes of the tetraacetate derivatives of 12-membered, 13-membered and 14-membered tetraazamacrocycles. Inorg Chim Acta. 1991;190:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurent S, Elst LV, Muller RN. Comparative study of the physicochemical properties of six clinical low molecular weight gadolinium contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:128–137. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferri D. On the Complex Formation Equilibria Between Indium(III) and Chloride Ions. Acta Chem Scand. 1972;26:733–746. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brucher E. Kinetic stabilities of gadolinium(III) chelates used as MRI contrast agents. Top Curr Chem Contrast Agents. 2002;I221:103–122. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cossy C, Merbach AE. Recent developments in solvation and dynamics of the lanthanide(III) Ions. Pure Appl Chem. 1988;60:1785–1796. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lincoln SF, Merbach AE. Substitution reactions of solvated metal ions. Adv Inorg Chem. 1995;42:1–88. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lincoln SF. Solvation, solvent exchange, and ligand substitution reactions of the trivalent lanthanide ions. Advances in Inorganic and Bioinorganic Mechanisms. 1986;4:217–87. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toth E, Brucher E, Lazar I, Toth I. Kinetics of formation and dissociation of lanthanide(III)-dota complexes. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:4070–4076. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu SL, Horrocks WD. Kinetics of complex-formation by macrocyclic polyaza polycarboxylate ligands - detection and characterization of an intermediate in the Eu3+-dota system by laser-excited luminescence. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:3724–3732. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang XY, Jin TZ, Comblin V, Lopezmut A, Merciny E, Desreux JF. A kinetic investigation of the lanthanide dota chelates - stability and rates of formation and of dissociation of a macrocyclic gadolinium(III) polyaza polycarboxylic MRI contrast agent. Inorg Chem. 1992;31:1095–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brucher E, Sherry AD. Kinetics of formation and dissociation of the 1,4,7-triazacyclonononane-N, N′, N″-triacetate complexes of cerium(III), gadolinium(III), and erbium(III) ions. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:1555–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brucher E, Laurenczy G, Makra Z. Studies on the kinetics of formation and dissociation of the cerium(III)-dota complex. Inorg Chim Acta 1. 1987;39:141–142. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balogh E, Tripier R, Fouskova P, Reviriego F, Handel H, Toth E. Monopropionate analogues of DOTA(4-) and DTPA(5-): kinetics of formation and dissociation of their lanthanide(III) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2007:3572–3581. doi: 10.1039/b706353a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balogh E, Tripier R, Ruloff R, Toth E. Kinetics of formation and dissociation of lanthanide(III) complexes with the 13-membered macrocyclic ligand TRITA(4-) Dalton Trans. 2005:1058–1065. doi: 10.1039/b418991d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moreau J, Pierrard JC, Rimbault J, Guillon E, Port M, Aplincourt M. Thermodynamic and structural properties of Eu3+ complexes of a new 12-membered tetraaza macrocycle containing pyridine and N-glutaryl groups as pendant arms: characterization of three complexing successive phases. Dalton Trans. 2007:1611–1620. doi: 10.1039/b700673j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moreau J, Guillon E, Pierrard JC, Rimbault J, Port M, Aplincourt M. Complexing mechanism of the lanthanide cations Eu3+, Gd3+, and Tb3+ with 1,4,7,10-tetrakis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (dota) - characterization of three successive complexing phases: study of the thermodynamic and structural properties of the complexes by potentiometry, luminescence spectroscopy, and EXAFS. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:5218–5232. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taborsky P, Svobodova I, Lubal P, Hnatejko Z, Lis S, Hermann P. Formation and dissociation kinetics of Eu(III) complexes with H(5)do3ap and similar dota-like ligands. Polyhedron. 2007;26:4119–4130. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taborsky P, Svobodova I, Hnatejko Z, Lubal P, Lis S, Forsterova M, Hermann P, Lukes I, Havel J. Spectroscopic characterization of Eu(III) complexes with new monophosphorus acid derivatives of H(4)dota. J Fluoresc. 2005;15:507–512. doi: 10.1007/s10895-005-2824-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kasprzyk SP, Wilkins RG. Kinetics of interaction of metal-ions with 2 tetraaza tetraacetate macrocycles. Inorg Chem. 1982;21:3349–3352. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brucher E, Cortes S, Chavez F, Sherry AD. Synthesis, equilibrium, and kinetic properties of the gadolinium(III) complexes of 3 triazacyclodecanetriacetate ligands. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:2092–2097. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kovacs Z, Sherry AD. pH-controlled selective protection of polyaza macrocycles. Synthesis. 1997:759–763. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szilagyi E, Toth E, Kovacs Z, Platzek J, Raduchel B, Brucher E. Equilibria and formation kinetics of some cyclen derivative complexes of lanthanides. Inorg Chim Acta. 2000;298:226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar K, Jin T, Wang X, Desreux JF, Tweedle MF. Effect of ligand basicity on the formation and dissociation equilibria and kinetics of Gd3+ complexes of macrocyclic polyamino carboxylates. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:3823–3829. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang CA, Liu YL, Chen CY, Chou XM. Ligand preorganization in metal ion complexation: molecular mechanics/dynamics, kinetics, and laser-excited luminescence studies of trivalent lanthanide complex formation with macrocyclic ligands TETA and DOTA. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:3448–3455. doi: 10.1021/ic001325j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forsterova M, Svobodova I, Lubal P, Taborsky P, Kotek J, Hermann P, Lukes I. Thermodynamic study of lanthanide(III) complexes with bifunctional monophosphinic acid analogues of H(4)dota and comparative kinetic study of yttrium(III) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2007:535–549. doi: 10.1039/b613404a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pasha A, Tircso G, Benyo ET, Brucher E, Sherry AD. Synthesis and characterization of DOTA-(amide)4 derivatives: equilibrium and kinetic behavior of their lanthanide(III) complexes. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2007:4340–4349. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200700354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baranyai Z, Banyai I, Brucher E, Kiraly R, Terreno E. Kinetics of the formation of [Ln(DOTAM)](3+) complexes. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2007:3639–3645. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brucher E, Sherry AD. Stability and toxicity of contrast agents, Chapter 6. In: Merbach AE, Toth E, editors. The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; Chichester: 2001. pp. 243–279. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wedeking P, Kumar K, Tweedle MF. Dissociation of gadolinium chelates in mice: relationship to chemical characteristics. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10:641–8. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90016-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Port M, Raynal I, Elst LV, Muller RN, Dioury F, Ferroud C, Guy A. Impact of rigidification on relaxometric properties of a tricyclic tetraazatriacetic gadolinium chelate. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:121–127. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cai HZ, Kaden TA. Metal-complexes with macrocyclic ligands. 36 Thermodynamic and kinetic studies of bivalent and trivalent metal-ions with 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-triacetic acid. Helv Chim Acta. 1994;77:383–398. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Comblin V, Gilsoul D, Hermann M, Humblet V, Jacques V, Mesbahi M, Sauvage C, Desreux JF. Designing new MRI contrast agents: a coordination chemistry challenge. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;186:451–470. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Faulkner S, Pope SJA, Burton-Pye BP. Lanthanide complexes for luminescence imaging applications. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2005;40:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bornhop DJ, Griffin JMM, Goebel TS, Sudduth MR, Bell B, Motamedi M. Luminescent lanthanide chelate contrast agents and detection of lesions in the hamster oral cancer model. Appl Spectrosc. 2003;57:1216–22. doi: 10.1366/000370203769699063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manning HC, Goebel T, Thompson RC, Price RR, Lee H, Bornhop DJ. Targeted molecular imaging agents for cellular-scale bimodal imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1488–1495. doi: 10.1021/bc049904q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.