Abstract

Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria have provided us with crucial insights into the process of solar energy capture, pathways of metabolic and societal importance, specialized differentiation of membrane domains, function or assembly of bioenergetic enzymes, and into the genetic control of these and other activities. Recent insights into the organization of this bioenergetic membrane system, the genetic control of this specialized domain of the inner membrane and the process by which potentially photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic cells protect themselves from an important class of reactive oxygen species will provide an unparalleled understanding of solar energy capture and facilitate the design of solar-powered microbial biorefineries.

Introduction

The capture of solar energy by photosynthetic organisms is at the foundation of almost all life on Earth. Photosynthesis conserves the energy within sunlight by transforming it into either chemical bond energy or a transmembrane electrochemical gradient. Photosynthetic activity generates atmospheric O2, which supports the respiration of heterotrophs, and provides reducing power to assimilate most of the CO2 that is sequestered in the biosphere. Consequently, there has been considerable interest in studying capture of light energy by plants and photosynthetic microbes.

Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria were historically classified by their ability to use sulfide as an electron donor for CO2 fixation, resulting in the terms purple sulfur bacteria (Chromatiaceae) and purple non-sulfur bacteria (Rhodospirillaceae) [1]. Photochemistry in anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria is dependent on enzymes that are ancestors of plant photosystems [1]. The presence of anoxygenic photosynthesis in bacterial groups that occupy different niches suggests that this capacity evolved either in independent events or as an early event that spread horizontally [2]. Among the Rhodospirillaceae, Rhodobacter species are often the best understood when one considers properties of the photosynthetic apparatus [3], the use of reducing power derived from solar energy [4-6], control of photosynthetic gene expression [7,8•, 9] or genomic perspectives [10-13]. Here we summarize new advances in these fields over the past two years.

The photosynthetic apparatus

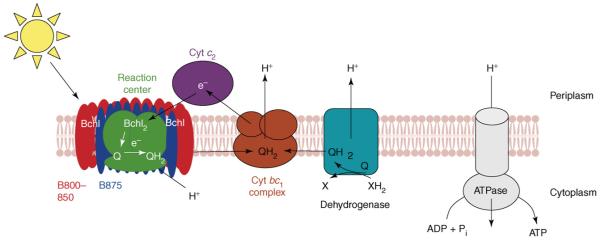

In Rhodobacter sphaeroides and related bacteria, solar energy is conserved by linking light-driven oxidation of a pair of bacteriochlorophyll molecules in a reaction center (RC) complex to electron transfer through membrane-bound bioenergetic enzymes (Figure 1). In this pathway, a periplasmically-positioned electron carrier (e.g. cytochrome cyt c2) reduces the photo-oxidized RC using electrons derived from quinone oxidation in the cyt bc1 complex [14,15]. The resulting formation of a proton gradient supports ATP synthesis.

Figure 1.

Cross-section of the R. sphaeroides ICM, illustrating the function of the major components of this bioenergetic membrane. The figure depicts the orientation of ICM components relative to the cytoplasmic and periplasmic compartments. Abbreviations: Bchl, bacteriochlorophyll; Bchl2, bacteriochlorophyll special pair; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Pi, phosphate; e-, electron; Q, ubiquinone; cyt c2, cytochrome c2; B800-850 & B875, light harvesting complexes, respectively.

The other and most abundant proteins within the R. sphaeroides photosynthetic apparatus are bacteriochlorophyll-containing and carotenoid-containing complexes, named B875 and B800-850 according to their absorption maxima [16], which harvest solar energy and funnel it to the RC. Approximately 14 B875 complexes surround and contact the RC, whereas the B800-850 complexes are positioned around the B875-RC complex [16,17]. It was believed that R. sphaeroides contained a single set of B800-850 polypeptides, but a second B800-850 complex has been discovered that can aid light-energy capture in this [18] and other photosynthetic bacteria [19].

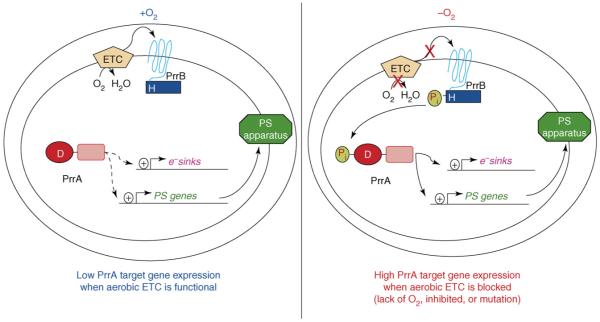

Analysis of purified R. sphaeroides photosynthetic membranes by atomic force microscopy (Figure 2) reveals an ordered array of particles with dimensions predicted from structural models of B875-RC and B800-850 complexes [20]. It is proposed that this supramolecular organization increases energy transfer efficiency from the B800-850 complexes to the B875-RC complexes [21,22].

Figure 2.

Supramolecular organization of ICM pigment-protein complexes. Sealed ICM vesicles (green) contain a high-density array of ordered pigment-protein complexes. In this array, each RC complex is surrounded by a series of B875 light harvesting complexes and are proposed to be coupled or linked with another B875-RC complex by the PufX protein. B875-RC pairs are arranged in a lattice, enabling tight ordered packing of ICM pigment-protein complexes. B800-850 light harvesting complexes are proposed to be arranged in pools two to three complexes wide between the B875-RC pairs. It is proposed that this ordered arrangement of pigment-protein complexes allows efficient energy transfer from B800-850 pigments to B875 pigments and to the RC special pair where photochemistry occurs.

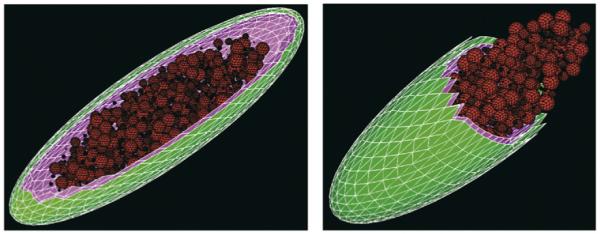

The Rhodobacter photosynthetic apparatus is housed in the intracytoplasmic membrane (ICM) vesicles, a region of the cytoplasmic membrane that protrudes from the cytoplasmic membrane into the cytoplasm (Figure 3). The cellular abundance of the ICM, as well as its pigment-protein composition, changes as a function of light intensity [21,23]; therefore there must be a mechanism to control formation of these invaginations and alter their pigment-protein composition. It is also possible that cellular factors help generate the ordered arrays of pigment-protein complexes within purified ICM vesicles. However, the cellular organization of the photosynthetic membrane and the structure of these arrays are altered in mutants lacking either carotenoids or B800-850 complexes [21], and so the pigment-protein complexes themselves might play a role in these aspects of photosynthetic membrane development.

Figure 3.

Cellular depiction of the R. sphaeroides ICM that houses the photosynthetic apparatus. This image shows the ICM (red spheres) protruding from the cytoplasmic membrane (purple) into the cytoplasm of this Gram-negative bacterium (outer membrane is green). Left panel: long-axis cross section of a cell. Right panel: short-axis cross section of a cell. These images were generated by digital reconstruction (Harold Trease, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, US Department of Energy) of sequential thin-section electron micrographs of photosynthetically grown cells (Samuel Kaplan, University of Texas Medical School at Houston) and are reproduced here with permission.

The ICM is physically connected to, but functionally distinct from, the cytoplasmic membrane (Figure 3) [23]. For example, the pigment-protein complexes are enriched in the ICM whereas phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes and penicillin-binding proteins are localized to the cytoplasmic membrane [23]. By contrast, ATPase and the cyt bc1 complex are found in both the cytoplasmic membrane and the ICM [23]. Having identified ~2000 proteins in whole photosynthetic cells [24], the protein blueprint of the ICM can now be mapped [25]. This will help to identify uncharacterized ICM proteins, define how the ICM is formed, determine how lipids or proteins are moved into this specialized membrane domain and understand how pigment-protein complexes are assembled.

Control of photosynthetic membrane development

Like other facultative anaerobes, many purple photosynthetic bacteria switch their mode of energy metabolism in response to changes in O2 tension. Pioneering studies by Cohen-Bazire [26] and Lascelles [27] showed that O2 negatively regulated ICM development because R. sphaeroides contained photosynthetic membranes under anaerobic conditions in the presence or absence of light. Transcription of so-called photosynthesis genes is now known to be positively and negatively regulated by O2 (for reviews, see [7,8 •,9,28,29]).

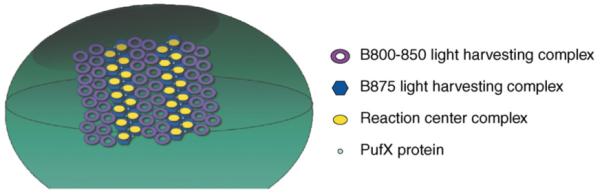

PrrBA (RegBA) is a master global regulator in Rhodobacter, related photosynthetic bacteria and other species [7,9]. PrrBA was discovered as an activator of photosynthesis genes, but it also directly controls genes involved in pigment synthesis, CO2 fixation, N2 fixation and H2 metabolism [4,7,30]. The emerging picture predicts that the PrrBA functions in a homeostatic feedback loop to balance the production of reducing power from light or other resources (when O2 is limiting) with induction of synthesis pathways that recycle excess reductant. The transcription factor in this pathway (PrrA/RegA) binds numerous promoters and activates transcription in vitro [4], its C-terminus contains a DNA binding motif from the Fis family of transcription factors [31,32], and target sites for this protein are predicted to exist upstream of numerous other, uncharacterized genes [7,8•]. Like many response regulators, PrrA activity increases upon phosphorylation [33], presumably because this stimulates PrrA dimerization [34], which is needed to activate transcription [35]. The ability of PrrA and its homologs [36] to weakly activate transcription in the absence of phosphorylation [30,33] could possibly explain expression of target genes in the presence of O2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Homeostatic control of gene expression by the PrrBA pathway. The left panel depicts the state of PrrA-dependent gene expression in the presence of O2. Under these conditions, the aerobic electron transport chain (ETC) is operative, the steady-state level of phosphorylated PrrA (PrrA-Pi) is low, and so there is a low basal level transcription of target genes (e.g. PS genes and electron sinks). The right panel depicts the state of PrrA-dependent gene expression under low O2 or anaerobic conditions. In this case, the lack of aerobic electron transport chain activity increases the steady state level of PrrA-Pi, which activates transcription of photosynthesis genes and gene products that recycle excess reducing power under anaerobic conditions.

PrrA phosphorylation is proposed to respond to changes in the oxidation/reduction state of the aerobic electron transport chain, because removing the cyt cbb3 terminal oxidase or blocking its activity increases expression of target genes in the presence of O2 [37]. The cognate histidine kinase of PrrA, PrrB/RegB, has been analyzed both as a full-length membrane protein [38] and as a C-terminal soluble domain [33,39]. When this and other features of PrrB are considered, it appears that its N-terminal membrane-spanning domain lowers the steady-state level of phosphorylated PrrA, possibly by stimulating PrrB phosphatase activity [38-40]. Precisely how activity of the aerobic electron transport chain controls function of the PrrBA pathway is not clear. However, purified cyt cbb3 oxidase can both transfer electrons to O2 (its traditional role) and alter the kinase and phosphatase activity of full-length PrrB in vitro [39]. PrrB also contains a quinone binding site [41], and so this kinase could receive multiple inputs from the respiratory chain as a way to control development or the composition of the photosynthetic apparatus.

Photosynthesis also requires a system(s) for recycling excess reducing power. This process is especially crucial for heterotrophic phototrophs (photoheterotrophs) that use organic carbon as a source of electrons in order to reduce light-oxidized RC complexes. For example, during photoheterotrophic growth at saturating light intensities, R. sphaeroides and other purple bacteria induce expression of the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, and use CO2 as an electron acceptor for excess reducing power, even when a fixed carbon source is present [4]. Likewise, the nitrogenase-dependent production of H2 by photoheterotrophic cultures grown in the presence of NH4+ (first observed by Gest and Kamen [42]) recycles excess reducing power [5]. R. sphaeroides and related bacteria also accumulate poly-hydroxybutyrate when supplied with excess carbon and reductant [6]. Global gene expression profiles and mutant analysis suggests that the R. sphaeroides RSP4157 gene cluster plays a heretofore unrecognized role in the recycling of reducing power under photoheterotrophic conditions [43]. It is not surprising to find that anoxygenic phototrophs are able to use a variety of pathways to recycle excess reducing power when one considers the myriad of electron donors and acceptors that these organisms are likely to encounter in nature. An additional link in the cycle of reducing power is seen by the ability of added electron acceptors to alter photosynthetic gene expression, and development of the photosynthetic apparatus [35,44-46].

The stress of solar energy generation

There are also deleterious consequences associated with converting light into biological energy. During solar energy capture, the excited chlorophyll pigments of the light-harvesting complexes can transfer their energy to O2, which generates the powerful oxidant singlet oxygen, 1O2 [47,48]. Carotenoids within pigment-protein complexes are one line of defense against 1O2 [47-49], but toxicity of this reactive oxygen species to photosynthetic cells means that carotenoid quenching does not provide total protection. The R. sphaeroides photosynthetic apparatus does not possess a water-splitting activity with which to evolve O2 but, if O2 is present, 1O2 is formed by energy transfer from excited, triplet-state chlorophyll pigments, to molecular oxygen and is bacteriocidal to these cells [47,50•]. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria can probably form 1O2 in nature because the photosynthetic apparatus is synthesized at the low O2 tensions present in the habitats that they inhabit [23].

A transcriptional response to 1O2 in vivo that requires the R. sphaeroides alternative sigma factor, σE has been described [50•]. R. sphaeroides σE activity is not increased by other reactive oxygen species (superoxide, hydrogen peroxide or hydroxyl radicals) [51,52], suggesting that this is a specific response to 1O2 [50•]. In the absence of 1O2, R. sphaeroides σE forms a complex with its cognate anti-sigma factor, ChrR [53], that prevents this sigma factor from forming a complex with RNA polymerase [54]. Thus, it is proposed that 1O2 somehow alters the σE-ChrR complex, releasing σE in order that this sigma factor is able to bind RNA polymerase and activate gene expression [50•].

1O2 is able to oxidize unsaturated fatty acids, destroy the integrity of bioenergetic membranes, inactivate enzymes or abolish the function of other biomolecules [48]. 1O2 is bacteriocidal to R. sphaeroides σE mutants when carotenoids are limiting [50•]; therefore, one or more σE-dependent gene products are required for viability under these conditions. Known σE target genes encode a periplasmic electron carrier (cyt c2), which, as with electron donors to the RC, is near the site of 1O2 formation, a putative cyclopropane fatty acid synthase, which could protect unsaturated fatty acids against peroxidation, and one of two σ32 homologs, RpoHII, which could activate expression of gene products that repair damaged proteins or aid assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus, as well as previously uncharacterized proteins that could protect cells from, or repair damage caused by 1O2 [50•]. Thus, phototrophs appear to have a dedicated stress-response that protects them from damage caused by 1O2, as well as repairing it.

Conclusion

Analysis of photosynthetic bacteria have provided crucial insights into the light reactions of photosynthesis, the formation of chemiosmotic ion gradients across biological membranes, the assembly of specialized membrane domains, and into how cells use reducing power generated by solar energy capture [1-5,23,55]. The completed genome sequences for several genera and species of anoxygenic phototrophs [10-13] mean that whole-genome and comparative genomic approaches [24,25,43,45,46] can now provide new insight into functions that control ICM development, assembly of the supramolecular arrays of pigment-protein complexes, formation and removal of toxic byproducts like 1O2, and into how cells partition reducing power derived from solar energy. This information will be crucial to tapping the ability of photosynthetic microbes to generate alternate energy supplies, to produce high-commodity carbon compounds, or to remove toxic compounds [6,9]. Finally, the microbial genome database predicts that many photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic bacteria contain homologs of pathways that have or are being analyzed in anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria [7,53]. Thus, fundamental insights into other biological systems will be derived from continued analysis of these fascinating bacteria.

Acknowledgements

Our analysis of photosynthesis has been supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM37509 and GM75273), the Department of Energy (ER63232-1018220-0007203 and DE-FG02-05ER15653), the University of Wisconsin-Madison Graduate School Research Committee or the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences (WIS04951). The authors thanks past and present members of the Donohue laboratory and Rhodobacter sphaeroides collaborators in the Kaplan (University of Texas Medical School at Houston) and Gomelsky (University of Wyoming) laboratories for generating data summarized in this paper.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Gest H, Blankenship R. Time line of discoveries: anoxygenic bacterial photosynthesis. Photosynth Res. 2004;80:59–70. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000030448.24695.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raymond J, Zhaxybayeva O, Gogarten JP, Blankenship RE. Evolution of photosynthetic prokaryotes: a maximum-likelihood mapping approach. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:223–230. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenship RE, Madigan MT, Bauer CE. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubbs JM, Robert Tabita F. Regulators of nonsulfur purple phototrophic bacteria and the interactive control of CO2 assimilation, nitrogen fixation, hydrogen metabolism and energy generation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:353–376. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludden P, Roberts G. Nitrogen fixation by photosynthetic bacteria. Photosynth Res. 2002;73:115–118. doi: 10.1023/A:1020497619288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee IH, Park JY, Kho DH, Kim MS, Lee JK. Reductive effect of H2 uptake and poly-β-hydroxybutyrate formation on nitrogenase-mediated H2 accumulation of Rhodobacter sphaeroides according to light intensity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsen S, Swem LR, Swem DL, Bauer CE. RegB/RegA, a highly conserved redox-responding global regulatory system. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:263–279. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.263-279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Mao L, Mackenzie C, Roh JH, Eraso JM, Kaplan S, Resat H. Combining microarray and genomic data to predict DNA binding motifs. Microbiology. 2005;151:3197–3213. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28167-0.The authors combine prior knowledge of transcription factors and computational approaches to predict the presence of additional target genes for global regulators and consensus motifs for regulators of the photosynthetic apparatus, some of which are also present in non-photosynthetic bacteria.

- 9.Zeilstra-Ryalls JH, Kaplan S. Oxygen intervention in the regulation of gene expression: the photosynthetic bacterial paradigm. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:417–436. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3242-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larimer FW, Chain P, Hauser L, Lamerdin J, Malfatti S, Do L, Land ML, Pelletier DA, Beatty JT, Lang AS, et al. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nbt923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reslewic S, Zhou S, Place M, Zhang Y, Briska A, Goldstein S, Churas C, Runnheim R, Forrest D, Lim A, et al. Whole-genome shotgun optical mapping of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5511–5522. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5511-5522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou S, Kvikstad E, Kile A, Severin J, Forrest D, Runnheim R, Churas C, Anantharaman TS, Hickman JW, Mackenzie C, et al. Whole-genome shotgun optical mapping of Rhodobacter sphaeroides strain 2.4.1. Genome Res. 2003;13:2142–2151. doi: 10.1101/gr.1128803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haselkorn R, Lapidus A, Kogan Y, Vlcek C, Paces J, Paces V, Ulbrich P, Pecenkova T, Rebrekov D, Milgram A, et al. The Rhodobacter capsulatus genome. Photosynth Res. 2001;70:43–52. doi: 10.1023/A:1013883807771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer TE, Donohue TJ. Cytochromes, iron-sulfur and copper proteins mediating electron transfer from the cytochrome bc1 complex to photosynthetic reaction center complexes. In: Blankenship RE, Madigan MT, Bauer CE, editors. Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria: Advances in Photosynthesis. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 725–745. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daldal F, Deshmukh M, Prince R. Membrane-anchored cytochrome c as an electron carrier in photosynthesis and respiration: past, present and future of an unexpected discovery. Photosynth Res. 2003;76:127–134. doi: 10.1023/A:1024999101226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cogdell RJ, Isaacs NW, Freer AA, Howard TD, Gardiner AT, Prince SM, Papiz MZ. The structural basis of light-harvesting in purple bacteria. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roszak AW, Howard TD, Southall J, Gardiner AT, Law CJ, Isaacs NW, Cogdell RJ. Crystal structure of the RC-LH1 core complex from Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Science. 2003;302:1969–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1088892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng X, Choudhary M, Kaplan S. A second and unusual pucBA operon of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: genetics and function of the encoded polypeptides. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6171–6184. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6171-6184.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cogdell R, Hashimoto H, Gardiner A. Purple bacterial light-harvesting complexes: from dreams to structures. Photosynth Res. 2004;80:173–179. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000030452.60890.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahatyrova S, Frese RN, Siebert CA, Olsen JD, van der Werf KO, van Grondelle R, Niederman RA, Bullough PA, Otto C, Hunter CN. The native architecture of a photosynthetic membrane. Nature. 2004;430:1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/nature02823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frese RN, Siebert CA, Niederman RA, Hunter CN, Otto C, van Grondelle R. The long-range organization of a native photosynthetic membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17994–17999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407295102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter C, Tucker J, Niederman R. The assembly and organisation of photosynthetic membranes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2005;4:1023–1027. doi: 10.1039/b506099k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiley PJ, Kaplan S. Molecular genetics of photosynthetic membrane biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:50–69. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.1.50-69.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callister SJ, Nicora CD, Zeng X, Roh JH, Dominguez MA, Tavano CL, Monroe ME, Kaplan S, Donohue TJ, Smith RD, Lipton MS. Comparison of aerobic and photosynthetic Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 proteomes. J Microbiol Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.021. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callister SJ, Dominguez MA, Nicora CD, Zeng X, Tavano CL, Kaplan S, Donohue TJ, Smith RD, Lipton MS. Application of the accurate mass and time tag approach to the proteome analysis of sub-cellular fractions obtained from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 aerobic and photosynthetic cell cultures. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1940–1947. doi: 10.1021/pr060050o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen-Bazire GW, Sistrom WR, Stanier RY. Kinetic studies of pigment synthesis by non-sulfur purple bacteria. J Cell Physiol. 1957;49:25–68. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030490104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lascelles J. The accumulation of bacteriochlorophyll precursors by mutant and wild-type strains of Rhodopseudomonas spheroides. Biochem J. 1966;100:175–183. doi: 10.1042/bj1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer CE, Elsen S, Bird TH. Mechanisms for redox control of gene expression. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:495–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pemberton J, Horne I, McEwan A. Regulation of photosynthetic gene expression in purple bacteria. Microbiology. 1998;144:267–278. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranson-Olson B, Jones DF, Donohue TJ, Zeilstra-Ryalls JH. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the role of PrrA in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 hemA gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3208–3218. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3208-3218.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laguri C, Phillips-Jones MK, Williamson MP. Solution structure and DNA binding of the effector domain from the global regulator PrrA (RegA) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides: insights into DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6778–6787. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DF, Stenzel RA, Donohue TJ. Mutational analysis of the C-terminal domain of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides response regulator PrrA. Microbiology. 2005;151:4103–4110. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comolli J, Carl A, Hall C, Donohue TJ. Transcriptional activation of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene P2 promoter by the response regulator PrrA. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:390–399. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.390-399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laguri C, Stenzel RA, Donohue TJ, Phillips-Jones MK, Williamson MP. Activation of the global gene regulator PrrA (RegA) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7872–7881. doi: 10.1021/bi060683g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karls RK, Wolf JR, Donohue TJ. Activation of the cycA P2 promoter for the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene by the photosynthesis response regulator. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:822–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comolli JC, Donohue TJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa RoxR, a response regulator related to Rhodobacter sphaeroides PrrA, activates expression of the cyanide-insensitive terminal oxidase, CioAB. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:755–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh JI, Kaplan S. Redox signaling: globalization of gene expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:4237–4247. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Potter CA, Ward A, Laguri C, Williamson MP, Henderson PJF, Phillips-Jones MK. Expression, purification and characterisation of full-length histidine protein kinase RegB from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:201–213. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh JI, Ko IJ, Kaplan S. Reconstitution of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cbb3-PrrBA Signal Transduction Pathway in vitro. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7915–7923. doi: 10.1021/bi0496440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oh J-I, Ko I-J, Kaplan S. The default state of the membrane-localized histidine kinase PrrB of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 is in the kinase-positive mode. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6807–6814. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6807-6814.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swem LR, Gong X, Yu C-A, Bauer CE. Identification of a ubiquinone-binding site that affects autophosphorylation of the sensor kinase RegB. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6768–6775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509687200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gest H, Kamen M. Photoproduction of molecular hydrogen by Rhodospirillum rubrum. Science. 1949;109:558. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2840.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tavano CL, Podevels A, Donohue TJ. Gene products required to recycle reducing power produced under photosynthetic conditions. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5249–5258. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5249-5258.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tavano CL, Comolli JC, Donohue TJ. The role of dor gene products in controlling the P2 promoter of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cytochrome c2 gene, cycA. Microbiol. 2004;150:1893–1899. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26971-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roh JH, Smith WE, Kaplan S. Effects of oxygen and light intensity on transcriptome expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: redox active gene expression profile. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9146–9155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pappas CT, Sram J, Moskvin OV, Ivanov PS, Mackenzie RC, Choudhary M, Land ML, Larimer FW, Kaplan S, Gomelsky M. Construction and validation of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 DNA microarray: transcriptome flexibility at diverse growth modes. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4748–4758. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4748-4758.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cogdell RJ, Howard TD, Bittl R, Schlodder E, Geisenheimer I, Lubitz W. How carotenoids protect bacterial photosynthesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355:1345–1349. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kochevar I. Singlet oxygen signaling: from intimate to global. Science Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment. 2004 doi: 10.1126/stke.2212004pe7. doi: 10.1126/stke.2212004pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glaeser J, Klug G. Photo-oxidative stress in Rhodobacter sphaeroides: protective role of carotenoids and expression of selected genes. Microbiology. 2005;151:1927–1938. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50•.Anthony JR, Warczak KL, Donohue TJ. A transcriptional response to singlet oxygen, a toxic byproduct of photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6502–6507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502225102.This paper provides the first demonstration that photosynthetic organisms mount a specific transcriptional response to singlet oxygen, it identifies a transcription factor that is required for this response, and it begins to identify genes that are part of the response to this bacteriocidal reactive oxygen species.

- 51.Zeller T, Moskvin OV, Li K, Klug G, Gomelsky M. Transcriptome and physiological responses to hydrogen peroxide of the facultatively phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7232–7242. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7232-7242.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeller T, Klug G. Detoxification of hydrogen peroxide and expression of catalase genes in Rhodobacter. Microbiology. 2004;150:3451–3462. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell E, Greenwell R, Anthony J, Wang S, Sofia H, Donohue T, Darst S. Insights into anti-sigma factor function revealed from analyzing the structure of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides sE-ChrR complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anthony J, Newman J, Donohue TJ. Interactions of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides ECF sigma factor, sE, with the anti-sigma factor, ChrR. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:345–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan S, Cain BD, Donohue TJ, Shepherd WD, Yen GS. Biosynthesis of the photosynthetic membranes of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J Cell Biochem. 1983;22:15–29. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]