Abstract

Objective

Patients with trauma-associated acute lung injury have better outcomes than patients with other clinical risks for lung injury, but the mechanisms behind these improved outcomes are unclear. We sought to compare the clinical and biological features of patients with trauma-associated lung injury with those of patients with other risks for lung injury and to determine whether the improved outcomes of trauma patients reflect their baseline health status or less severe lung injury, or both.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Analysis of clinical and biological data from 1,451 patients enrolled in two large randomized, controlled trials of ventilator management in acute lung injury.

Measurements and Main Results

Compared with patients with other clinical risks for lung injury, trauma patients were younger and generally less acutely and chronically ill. Even after adjusting for these baseline differences, trauma patients had significantly lower plasma levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, von Willebrand factor antigen, surfactant protein-D, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1, which are biomarkers of lung epithelial and endothelial injury previously found to be prognostic in acute lung injury. In contrast, markers of acute inflammation, except for interleukin-6, and disordered coagulation were similar in trauma and nontrauma patients. Trauma-associated lung injury patients had a significantly lower odds of death at 90 days, even after adjusting for baseline clinical factors including age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidities, and severity of illness (odds ratio, 0.44; 95% confidence interval, 0.24 – 0.82; p = .01).

Conclusions

Patients with trauma-associated lung injury are less acutely and chronically ill than other lung injury patients; however, these baseline clinical differences do not adequately explain their improved outcomes. Instead, the better outcomes of the trauma population may be explained, in part, by less severe lung epithelial and endothelial injury.

Keywords: respiratory distress syndrome, adult, multiple trauma, biological markers

Acute lung injury (ALI) and its more severe form, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), may result from a variety of different initial insults, including sepsis, aspiration, pneumonia, multiple transfusions, and trauma (1). The recognition that patients with ALI are a heterogeneous group has led to significant advances in understanding the pathogenesis of the syndrome (2). An increasing body of literature strongly suggests that the pathogenesis of ALI may vary with the clinical risk factor that precedes the development of ALI. Multiple studies have reported that trauma-related ALI has a lower mortality than ALI owing to other clinical risk factors (3–7). Moreover, a recent study found that ALI does not increase mortality in patients with trauma (8), in contrast to other studies that have shown that ALI significantly increases mortality in septic patients (9, 10).

Prior studies also have suggested that trauma-related ALI may differ pathophysiologically from nontrauma–related ALI. Previous studies of biological specimens from patients with ALI have demonstrated the utility of plasma biomarkers both for predicting patient outcomes and for providing important insights into disease pathogenesis (11–14). Patients with trauma-related ALI had lower levels of biomarkers that reflect endothelial activation—von Willebrand factor antigen (vWF), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and E-selectin—than patients with sepsis as a risk factor for ALI, even after controlling for severity of illness (15). Similarly, previous studies of patients from the ARDS Network's trial of low tidal volume ventilation noted that levels of vWF were significantly lower in trauma patients than in patients with other risks for lung injury (16).

Although these prior studies have suggested clinical and biological differences between trauma-related ALI and other risk groups, many of the clinical characteristics of trauma-related ALI patients have not been fully described, and many of the biomarkers found to be prognostic in ALI have not been specifically analyzed in trauma patients. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the biological features and clinical outcomes of trauma-related ALI reflect unique characteristics of this subgroup, or whether they simply reflect baseline differences presumed to exist between trauma patients and nontrauma patients with respect to age, comorbidities, and severity of illness. If trauma-related ALI has unique clinical and biological features, and particularly if its clinical outcomes differ beyond what would be expected based on demographic characteristics, our understanding of the pathogenesis of ALI may be expanded, and future trial designs may be altered.

To address these issues, we analyzed clinical and biological data from 1,451 patients enrolled in two ARDS Network trials of ventilation strategies in ALI/ARDS: the landmark trial of low tidal volume ventilation published in 2000 and the Assessment of Low Tidal Volume and Increased End-Expiratory Volume to Obviate Lung Injury (ALVEOLI) trial of low vs. high levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) (17, 18). Our study had three aims: a) to compare the clinical features of trauma-associated ALI with those of ALI owing to other clinical risk factors; b) to compare the biomarker profile of trauma-associated ALI with that in ALI owing to other clinical risk factors; and c) to determine whether differences in clinical outcomes between patients with trauma-related ALI and nontrauma–related ALI are attributable to the differences in baseline characteristics of these two groups, or to differences in severity of lung injury, or both.

METHODS

Data for this study were obtained from patients enrolled in two of the large randomized clinical trials of ventilation strategy conducted by the ARDS Network (17, 18). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar in the two trials and are described in the original publications (17, 18). The institutional review boards of all involved hospitals approved both trials, and all patients or surrogates provided informed consent with the exception of those enrolled in the low tidal volume trial at one hospital, where the requirement was waived (17).

Original Studies

The first study, referred to as the low tidal volume trial, enrolled 861 patients to test the hypothesis that ventilation with a low tidal volume, plateau pressure-limited strategy would reduce mortality in patients with ALI (17). Details of the trial have been published in full (17). Briefly, patients were randomized to ventilation with a tidal volume of either 6 or 12 mL/kg predicted body weight; once the benefit of the lower tidal volume strategy had been demonstrated, an additional 41 patients were assigned to the lower tidal volume to complete a trial of lisofylline vs. placebo and also are included in this analysis (19). Clinical data and plasma samples for biomarker measurements were collected at baseline before randomization; all patients were followed until death, day 180, or discharge home with unassisted breathing. The trial demonstrated a significant reduction in 180-day mortality in the low tidal volume treatment group (31% vs. 40%; p = .007). In a factorial design, ketoconazole (20) and lisofylline (19) also were administered to subsets of patients as investigational therapies for acute lung injury, neither of which affected mortality.

The second study, referred to as ALVEOLI, enrolled 549 patients to test the hypothesis that higher levels of PEEP would reduce mortality in patients with ALI (18). Details of the trial have been published in full (18). Briefly, patients were randomized to ventilation with either a lower PEEP or higher PEEP strategy. Clinical data and plasma samples for biomarker measurements were collected at baseline before randomization; patients were followed until death, day 90, or discharge home with unassisted breathing. The data safety and monitoring board terminated the trial after enrollment of 549 patients on the basis of futility. The trial found no difference in 90-day mortality and no modulation of circulating interleukin (IL)-6, surfactant protein D (SP-D), or ICAM-1 with higher vs. lower levels of PEEP.

The etiology of ALI was determined in both trials by the site investigator; in cases in which more than one potential cause of ALI was present, the site investigator determined which was the principal cause.

Plasma Biomarkers

We analyzed baseline (day 0) plasma levels of eight biomarkers found in previous studies to be associated with severity and outcomes in ALI to determine whether levels differed significantly in trauma patients as compared with nontrauma patients. The eight biomarkers—ICAM-1, vWF, protein C, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), SP-D, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFr-1), and ILs-6 and -8 — reflect different aspects of the pathophysiology of ALI and are described in more detail in the Discussion section. Biomarker measurements were performed using identical assay techniques by the same laboratories for both studies. Details of the methods used to measure the biomarkers have been published in full elsewhere (16, 21–26). Biomarkers were missing in some patients, primarily in patients from the low tidal volume study. In that cohort, plasma was not available on all patients, primarily those patients in the ketoconazole or lisofylline arms of the study because of the additional plasma required to measure drug levels in these patients.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata 8.2 (Stata, College Station, TX). To compare the baseline characteristics of trauma patients with those of nontrauma patients, we used the chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables, Student's t-test with the unequal variance assumption for normally distributed variables, and Mann-Whitney U tests for variables not normally distributed. Normality was assessed by quantile-quantile plots and other qualitative graphical methods, and all p values are two-tailed.

To compare baseline levels of the biomarkers, none of which were normally distributed, we used Mann-Whitney U tests. We then natural log-transformed the biomarker data to perform multivariable linear regression to control for baseline clinical features that differed between trauma and nontrauma patients such as age, comorbidities, and severity of illness. This analysis was designed to determine whether biomarker levels differed between trauma and nontrauma patients because of preexisting characteristics of the patient populations such as baseline health status, demographic differences, or chronic disease. Model checking was performed using residual-based diagnostics. To examine the impact of missing biomarker data, we performed a sensitivity analysis using sampling weights. We first developed linear regression models to predict the probability of each biomarker being measured for each patient. The original linear regression models (in which log-transformed biomarker levels were the outcome variable) were then refitted using the inverse predicted probabilities as sampling weights; in this way, patients who had a particular biomarker measured but whose clinical characteristics suggested they would have been likely to have missing data would be heavily weighted. With these sampling weights included in the original linear models, the results were substantively unchanged for all the biomarkers, and the unweighted results are reported.

We performed logistic regression to determine the odds of mortality in patients with trauma-related ALI compared with those with other clinical risks for ALI. We chose 90-day mortality as the primary outcome because data through 90 days was available for patients in both trials. To determine whether outcome differences were determined primarily by the patients’ baseline health status, we then constructed a multivariable logistic model to adjust for baseline differences in demographics, comorbidities found on bivariate analysis to differ between the two groups, use of low tidal volume ventilation, Acute Physiology, Age and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III score (27), and Pao2/Fio2 ratio. These covariates were selected on the basis of the bivariate analysis results and on face validity (28). As a sensitivity analysis, we also performed a manual backward-selection procedure incorporating all of the predictors that were statistically significant (p < .05) on bivariate analysis (29) with stepwise exclusion of covariates with p > .20 and serial iterations of the likelihood ratio test; the results obtained with this model did not differ significantly from those obtained with the first model. The model fit was analyzed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the linktest for specification errors in the logistic model (28).

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics

Trauma patients comprised approximately 10% of the overall population of patients in the two trials (Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the patients, stratified by trauma, are summarized in Table 1. As compared with patients with other clinical risk factors for ALI, trauma patients were younger and more likely to be white. Trauma patients also were significantly less likely to have a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, recent immunosuppression, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis. Furthermore, trauma patients had significantly lower APACHE III scores than nontrauma patients (mean score, 67 ± 25 in trauma vs. 89 ± 30; p < .001).

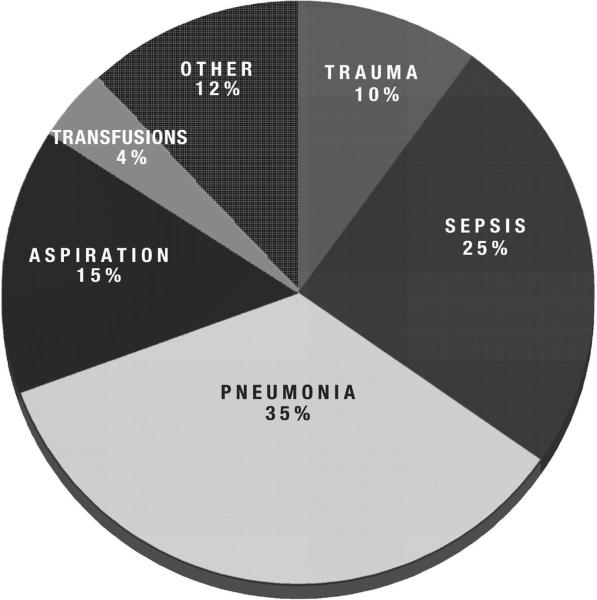

Figure 1.

Primary etiology of acute lung injury in patients in the low tidal volume (n = 902) and Assessment of Low Tidal Volume and Increased End-Expiratory Volume to Obviate Lung Injury (n = 549) trials. Patients with trauma-associated lung injury comprised approximately 10% (n = 141) of the overall study population.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and comorbidities of patients with trauma-related and nontrauma-related acute lung injury

| Characteristic | Trauma (n = 141) | Nontrauma (n = 1307) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (sd), yrs | 44 (17) | 52 (17) | <.001 |

| Female gender, no. (%) | 89 (63) | 750 (57) | .18 |

| Race-ethnicity, no. (%)a | .036 | ||

| White | 118 (84) | 955 (73) | |

| Black | 10 (7) | 222 (17) | |

| Latino | 7 (5) | 79 (6) | |

| Asian | 3 (2) | 41 (3) | |

| AIDS, no. (%) | 1 (0.7) | 83 (6.4) | .003 |

| Leukemia, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 27 (2.1) | .10 |

| Lymphoma, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 16 (1.2) | .39 |

| Solid tumor with metastases, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 24 (1.8) | .16 |

| Immunosuppression within past 6 mos, no. (%)b | 2 (1.5) | 180 (13.8) | <.001 |

| Liver failure plus coma or encephalopathy, no. (%) | 1 (0.7) | 12 (0.9) | 1.0 |

| Cirrhosis, no. (%) | 2 (1.5) | 43 (3.3) | .31 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 5 (3.7) | 204 (15.7) | <.001 |

| Chronic dialysis, no. (%) | 0 (0) | 38 (2.9) | .044 |

| Enrolled in the low tidal volume trial | 96 | 806 | — |

| Low tidal volume arm of ARMA, no. (%) | 59 (61) | 414 (51) | .06 |

| Enrolled in ALVEOLI | 45 | 504 | — |

| Low PEEP arm of ALVEOLI, no. (%) | 26 (58) | 247 (49) | .26 |

| APACHE III score, mean (sd) | 67 (25) | 89 (30) | <.001 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ALVEOLI, Assessment of Low Tidal Volume and Increased End-Expiratory Volume to Obviate Lung Injury; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; APACHE, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation.

Total may not equal 100% because of additional categories with very small numbers of patients

immunosuppression defined as radiation, chemotherapy, or prednisone at doses ≥0.3 mg/kg per day. Comparisons by Student's t-test, chi-square, or Fisher's exact test.

Compared with nontrauma patients, trauma patients had a higher mean arterial pressure (mean, 70 mm Hg compared with 61 mm Hg in nontrauma patients; p < .001) and a lower incidence of vasopressor administration (odds ratio [OR], 0.38 comparing trauma to nontrauma patients; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24 – 0.62), suggesting a lower prevalence of hypotension in the trauma group (Table 2). In addition, trauma patients had a higher urine output in the 24 hrs preceding enrollment than nontrauma patients (median urine output, 2300 vs. 1843 mL; p < .001).

Table 2.

Baseline nonrespiratory physiologic measurements in trauma and nontrauma patients with acute lung injury

| Parameter | Trauma (n = 141) | Nontrauma (n = 1307) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum temperature, °C | 38.5 (0.75) | 38.5 (0.95) | .72 |

| Minimum temperature, °C | 36.9 (0.95) | 36.7 (0.97) | .06 |

| Lowest MAP, mm Hg | 70 (12) | 61 (13) | <.001 |

| Highest MAP, mm Hg | 107 (16) | 101 (20) | <.001 |

| Highest heart rate, mm Hg | 128 (22) | 126 (23) | .48 |

| Urine output, median (IQR), mL | 2300 (1754–3530) | 1843 (1112–2930) | <.001 |

| Vasopressors required, no. (%)a | 21 (17.6) | 393 (35.8) | <.001 |

| Net fluid balance during 24 hrs before enrollment (no. of liters)b | +1.799 | +1.731 | .69 |

MAP, mean arterial pressure; IQR, interquartile range.

Odds ratio for use of any vasopressor within prior 24 hrs in trauma patients compared with nontrauma patients: 0.38 (0.24–0.62)

data available for subjects enrolled in the low tidal volume trial only. All values represent mean (sd) except where indicated; all values from within 24 hrs before enrollment. Comparisons using Student's t-test with unequal variance assumption or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Baseline measures of respiratory physiology and ventilator settings before trial enrollment are summarized in Table 3. Trauma patients had a lower mean respiratory rate (18 vs. 21; p < .001) and minute ventilation (11.6 vs. 12.8 L/min; p < .001) than nontrauma patients. The Pao2/Fio2 ratio was significantly higher in trauma patients (median, 164 vs. 114; p < .001). Baseline tidal volume and tidal volume expressed in mL/kg predicted body weight did not differ between trauma and nontrauma patients. Peak, plateau, and end-expiratory pressures were significantly higher in trauma than nontrauma patients. However, the difference in plateau pressure likely was linked to the difference in PEEP; both were 2 cm.

Table 3.

Baseline respiratory physiology and ventilatory parameters in trauma versus nontrauma lung injury patients

| Parameter | Trauma (n = 141) | Nontrauma (n = 1307) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory rate, total | 18 (7) | 21 (7) | <.001 |

| Minute ventilation, L | 11.6 (3.9) | 12.8 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Tidal volume, mL | 663 (184) | 635 (173) | .09 |

| Tidal volume/PBW, mL/kg | 9.8 (2.7) | 10.0 (2.7) | .39 |

| PEEP, median (IQR), cm H2O | 10 (5–12) | 8 (5–10) | .038 |

| Plateau pressure, cm H2Oa | 30.7 (8.0) | 28.7 (7.7) | .018 |

| Peak pressure, cm H2O | 39.8 (11.0) | 35.1 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Pao2/Fio2 ratio, median (IQR) | 164 (108–202) | 114 (82–157) | <.001 |

| Clinical Lung Injury score, median (IQR)b | 2.75 (2.25–3) | 2.75 (2.5–3.25) | .10 |

| Quasistatic compliance, mL/cm H2O | 32.0 (15.7) | 32.7 (26.0) | .70 |

| Mean airway pressure, cm H2O | 16.5 (5.8) | 15.6 (5.2) | .11 |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 40.5 (7.1) | 37 (8.7) | <.001 |

| Arterial pH | 7.41 (0.06) | 7.39 (0.08) | .03 |

PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; IQR, interquartile range.

Trauma patients were more likely to be missing plateau pressure: 41/141 (29%) vs. 273/1310 (21%); odds ratio 1.56 (1.06–2.29)

calculated as Murray et al (30). All values represent mean (sd) except where indicated; all values from within 24 hrs before enrollment. Comparisons made with Student's t-test with unequal variance assumption or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Relevant laboratory values and radiographic findings are detailed in Table 4. Trauma patients had a significantly lower hematocrit, platelet count, and white blood cell count than nontrauma patients. Furthermore, trauma patients had lower creatinine and albumin and higher bicarbonate than nontrauma patients. As expected, trauma patients had a higher rate of pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and tube thoracostomy than nontrauma patients.

Table 4.

Baseline laboratory and radiographic data in trauma and nontrauma patients with acute lung injury

| Parameter | Trauma (n = 141) | Nontrauma (n = 1307) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit, % | 28.1 (4.7) | 30.0 (5.9) | <.001 |

| Platelets, median (IQR), thousands/μL | 89 (67–130) | 147 (84–233) | <.001 |

| White blood cells, median (IQR), thousands/μL | 11.5 (8.2–15.1) | 13 (8.9–18.5) | .004 |

| Creatinine, median (IQR), mg/dLa | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | <.001 |

| Bicarbonate, mEq/Lb | 23.6 (4.3) | 21.3 (5.6) | <.001 |

| Bilirubin, median (IQR), mg/dLc | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | .29 |

| Albumin, g/dLd | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.2 (0.6) | .006 |

| Radiographic lung injury score, median (IQR) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (4–4) | .18 |

| Pneumothorax, no. (%) | 10 (7.1) | 32 (2.4) | .0018 |

| Subcutaneous emphysema, no. (%) | 22 (15.8) | 20 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Pneumomediastinum, no. (%) | 5 (3.6) | 19 (1.5) | .06 |

| Pneumatoceles, no. (%) | 5 (3.5) | 33 (2.5) | .47 |

| Tube thoracostomy, no. (%) | 76 (53.9) | 113 (8.6) | <.001 |

IQR, interquartile range.

To convert to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4

equivalent to mmol/L

to convert to μmol/L, multiply by 17.1

to convert to g/L, multiply by 10. All values represent mean (sd) except where indicated. Comparisons made with chi-square test, Student's t-test with unequal variance assumption, or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

Biomarkers

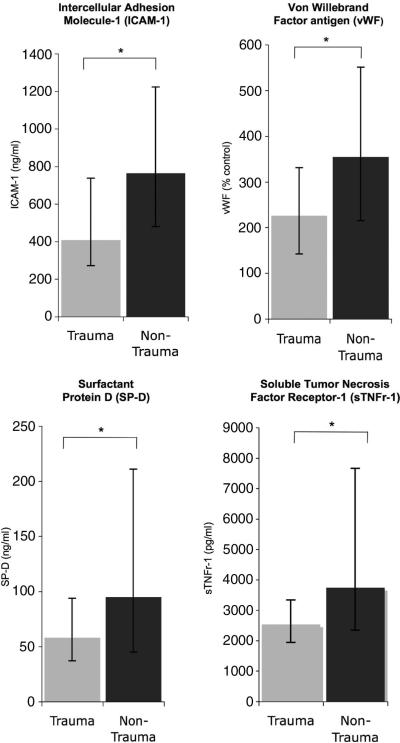

We compared baseline (day 0) plasma levels of eight biomarkers in patients with trauma-related ALI with patients with other clinical risks for lung injury (Table 5). On bivariate analysis, trauma patients had significantly lower baseline levels of ICAM-1, SP-D, vWF, PAI-1, IL-8, and sTNFr-1 than nontrauma patients. Levels of IL-6 and protein C were not significantly different. In a multivariable model that controlled for age, ethnicity, significant baseline co-morbidities (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, immunosuppression, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease), APACHE III score, and Pao2/Fio2, trauma remained significantly associated with lower levels of ICAM-1, SP-D, vWF, and sTNFr-1 (Table 5). Figure 2 shows the magnitude of differences in these four key biomarkers. Although levels of IL-6 did not significantly differ between trauma and nontrauma patients in an unadjusted analysis, levels were statistically higher among trauma patients in the multivariate analysis.

Table 5.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of baseline biomarker levels in patients with acute lung injury

| Biomarker, Day 0 | n | Median Value, Trauma | Median Value, Nontrauma | Unadjusted p Value | Multivariable p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-1, ng/mL | 1307 | 410 (272–738) | 765 (480–1223) | <.001 | <.001 |

| SP-D, ng/mL | 1075 | 58 (37–94) | 95 (45–211) | <.001 | .001 |

| Protein C, % of control | 1308 | 58 (45–78) | 53 (35–84) | .07 | .14 |

| vWF, % of control | 1088 | 226 (142–331) | 355 (215–551) | <.001 | <.001 |

| PAI-1, ng/mL | 1304 | 56 (36–104) | 70 (37–157) | .045 | .95 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 1302 | 300 (128–674) | 259 (100–850) | .44 | .047 |

| IL-8, pg/mL | 1309 | 21 (20–59) | 44 (20–103) | .002 | .30 |

| sTNFr-1, pg/mL | 1091 | 2535 (1945–3332) | 3748 (2340–7661) | <.001 | .004 |

ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; SP-D, surfactant protein D; vWF, von Willebrand factor antigen; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor; IL, interleukin; sTNFr, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor.

All biomarker values represent median (interquartile range) with bivariate comparison using Mann-Whitney U test. Multivariable linear model (using natural log-transformed biomarker levels) controls for age, gender, ethnicity, presence of significant comorbidities (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, immunosuppression, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease), severity of injury, and Pao2/Fio2 ratio.

Figure 2.

Trauma-associated acute lung injury patients have lower levels of plasma biomarkers of endothelial and epithelial injury than patients with other clinical risk factors for acute lung injury. *p < .001 for all comparisons in unadjusted model; p ≤ .001 for all comparisons in multivariable model using natural log-transformed biomarkers that adjusts for age, gender, race and ethnicity, comorbidities, severity of illness, and Pao2/Fio2 ratio. Median values are depicted; error bars represent 25% to 75% interquartile range.

Outcomes

In an analysis that controlled only for treatment with low tidal volume ventilation, the odds of mortality at 90 days for trauma patients were significantly lower than those for nontrauma patients (Table 6) (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.12–0.38; p < .001). After adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, significant comorbidities (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, immunosuppression, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease), use of the low tidal volume strategy, APACHE III score, and Pao2/Fio2, the odds of death for trauma patients were still significantly lower than those for nontrauma patients (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.24 – 0.82; p = .01). Additional adjustments for initial study group (low tidal volume trial vs. ALVEOLI) and ketoconazole and lisofylline use had no impact on the results, nor did an additional adjustment for sepsis as the etiology of ALI (in model including sepsis: OR, 0.44 for impact of trauma on mortality; p = .01; p value for sepsis covariate, 0.50). Likewise, it did not significantly impact the results when we included all chronic medical conditions in the model or when we restricted the analysis to patients without a history of chronic illness.

Table 6.

Odds of death at 90 days for patients with trauma-associated acute lung injury (ALI) compared to patients with other clinical risks for ALI

| Model | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for low tidal volume strategy only | 0.21 | 0.12–0.38 | <.001 |

| Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, low tidal volume strategy, comorbidities,a APACHE III score, and Pao2/Fio2 ratiob | 0.44 | 0.24–0.82 | .01 |

CI, confidence interval; APACHE, Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation.

Comorbidities included were those that were significant on bivariate analysis: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, immunosuppression, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease

model fit by Hosmer-Lemeshow test p = .18; linktest for specification errors “hatsq” p = .55.

We then added the biomarkers that were significantly lower in trauma patients (ICAM-1, SP-D, vWF, and sTNFr-1) as covariates in the multivariable model, in order to determine whether decreased biological activity of the pathways these markers reflect may mediate the observed difference in mortality. Adding the biomarkers to the model notably attenuated the difference in mortality between trauma-associated ALI and nontrauma–associated ALI, such that the difference was no longer statistically significant (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.31–1.43).

Trauma patients also had significantly more ventilator-free days than nontrauma patients in an unadjusted analysis (median, 17 ventilator-free days for trauma patients vs. 14 ventilator-free days for nontrauma patients; p = .03). Given the unusual distribution of this variable (i.e., the large number of patients with 0 ventilator-free days, generating a very abnormal distribution even with log-transformation), we did not apply multivariable linear models to this comparison.

DISCUSSION

We found that patients with trauma-associated ALI had markedly different clinical characteristics than patients with other clinical risks for ALI in a population enrolled in two ARDS Network randomized, controlled trials. Specifically, compared with patients with other risks for ALI, trauma patients were younger and less chronically ill, and their acute illness was generally less severe. In addition, patients with trauma-associated ALI had lower plasma levels of several biomarkers previously found to be associated with poor clinical outcomes in ALI, including ICAM-1, SP-D, sTNFr-1, and vWF; these differences persisted even after adjusting for the patients’ baseline clinical differences. Finally, we found that patients with trauma-associated ALI had strikingly better clinical outcomes than patients with other risks for ALI, even after adjusting for baseline clinical differences.

Our work expands on previous findings in several ways. First, this study comprehensively describes the clinical features of trauma-associated ALI in a large cohort and confirms that these patients are younger, healthier, and generally less acutely ill than others with ALI. Second, this study demonstrates that plasma levels of biomarkers of endothelial and lung epithelial injury are significantly lower in trauma patients, even after adjusting for clinical differences, in contrast to markers of acute inflammation and disordered coagulation. Third, we found that the baseline clinical characteristics of trauma patients in this study population do not adequately explain their improved clinical outcomes. Our results suggest that trauma patients have on average less severe lung epithelial and endothelial injury than patients with other clinical risks for ALI, a finding that may be partially responsible for their better clinical outcomes.

The biomarker data presented here also provide insight into the pathophysiology of trauma-related ALI. The eight biomarkers studied—ICAM-1, vWF, protein C, PAI-1, SP-D, sTNFr-1, IL-6, and IL-8 — have been shown in prior studies to reflect the severity of ALI. ICAM-1 and vWF are both considered markers of endothelial injury and have been associated with poor outcomes in ALI patients (12, 16, 30, 31). Protein C and PAI-1 are markers of disordered coagulation and fibrinolysis previously demonstrated to predict clinical outcomes in patients with lung injury (24, 26). SP-D reflects lung epithelial cell injury and is similarly prognostic in patients with ALI (23). STNFr-1 is released both by the lung epithelium and by neutrophils binding to the endothelium during acute inflammation; elevated levels have been associated with increased mortality in ALI patients (21). Finally, IL-6 and IL-8 are cytokines that reflect acute systemic inflammation and are prognostic of poor clinical outcomes in patients with ALI (22). Several of these markers (IL-6, IL-8, SP-D, and sTNFr1) also have been demonstrated to be decreased over time by a lung-protective ventilation strategy (21–23), confirming their critical role in the pathogenesis and outcomes of ALI. The lower levels of ICAM-1, vWF, SP-D, and sTNFr-1 in trauma patients in this study may reflect less severe endothelial (vWF, ICAM-1) and epithelial (SP-D, sTNFr-1) injury in the lungs of patients with trauma-related ALI (13, 32–36). Instead, the primary insult in trauma-related ALI may be one of systemic inflammation and disordered coagulation, as reflected by levels of IL-6, IL-8, protein C, and PAI-1 that were similar to (or higher than, in the case of IL-6) those in other causes of ALI (22, 37).

The finding that adjusting for baseline levels of ICAM-1, SP-D, vWF, and sTNFr-1 attenuated the reduced mortality of trauma patients may be explained by one of several mechanisms, any of which may account for the loss of independent association between trauma and improved survival. It may be that decreased activity of the pathways reflected by these biological markers mediates part of the observed difference in mortality—in other words, that trauma patients have less severe endothelial and lung epithelial injury, which leads to a lower risk of death. Alternatively, these biomarkers may reflect different aspects of severity of illness than those captured by APACHE III or those included in our backward selection model. It is also possible that adding these four additional variables primarily increased the variance of the trauma parameter; however, it should be noted that the addition of each one of the biomarkers alone to the model resulted in significant attenuation of the odds ratio for trauma, such that the effect of trauma on mortality was no longer statistically significant (data not shown). In contrast, adding the other four biomarkers (IL-6, IL-8, PAI-1, and protein C) to the logistic model as a sensitivity analysis did not significantly impact the coefficient or variance of the trauma parameter. This analysis suggests that increased variance alone is unlikely to explain the effect of including these markers in the model.

This study has several limitations. First, we do not have information on the rates of direct chest trauma vs. indirect trauma–related lung injury. Tube thoracostomy may be a surrogate marker for direct chest trauma, and was not found to be a significant covariate in any of our multivariate analyses; nevertheless, we cannot rule out significant differences between patients with direct vs. indirect pulmonary trauma (38). Likewise, injury severity scores, commonly used to grade the severity of traumatic injury, were not collected (39). Second, we do not have complete data on either the overall volume of fluids received by patients in the trial or on their central venous or pulmonary artery occlusion pressures. Third, biomarkers were not measured in all patients. Biomarker measurements were made purely on the basis of plasma availability; within trauma patients, there were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, APACHE III score, or significant comorbidities between patients who did and did not have all biomarkers measured. In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis using sampling weights, described in the methods section, which did not significantly impact the results. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out some degree of selection bias in the biomarker measurements. Fourth, patients with trauma-associated ALI likely were cared for by different physicians than patients with nontrauma–associated ALI (i.e., surgical vs. medical intensivists); thus, practice variation may be in part responsible for some of the observed differences between these two groups of patients. Finally, we studied patients enrolled in randomized, controlled trials, which tend to select patients healthier than the overall population of all patients with disease.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in a study sample of patients enrolled in two ARDS Network randomized, controlled trials, we found that patients with trauma-related lung injury were younger and less acutely and chronically ill than their counterparts with other clinical risks for lung injury. The trauma patients had lower levels of plasma markers of lung epithelial and endothelial injury (ICAM-1, vWF, SP-D, and sTNFr-1), indicating that the pathophysiology of trauma-related ALI may be different from that of the broader population of lung injury patients. Perhaps most importantly, patients with trauma-related ALI had a lower odds of death than those with nontrauma–related ALI, even after controlling for baseline demographic and clinical differences. Given these results, future trials in acute lung injury should consider stratifying by trauma.

APPENDIX

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network

Network Participants. Cleveland Clinic Foundation: Herbert P. Wiedemann, MD*; Alejandro C. Arroliga, MD; Charles J. Fisher, Jr, MD; John J. Komara, Jr, BA, RRT; Patricia Periz-Trepichio, BS, RRT. Denver Health Medical Center: Polly E. Parsons, MD. Denver VA Medical Center: Carolyn Welsh, MD. Duke University Medical Center: William J. Fulkerson, Jr, MD*; Neil MacIntyre, MD; Lee Mallatratt, RN; Mark Sebastian, MD; John Davies, RRT; Elizabeth Van Dyne, RN; Joseph Govert, MD. Johns Hopkins Bay-view Medical Center: Jonathan Sevransky, MD; Stacey Murray, RRT. Johns Hopkins Hospital: Roy G. Brower, MD; David Thompson, MS, RN; Henry E. Fessler, MD. LDS Hospital: Alan H. Morris, MD*; Terry Clemmer, MD; Robin Davis, RRT; James Orme, Jr, MD; Lindell Weaver, MD; Colin Grissom, MD; Frank Thomas, MD; Martin Gleich, MD (posthumous). McKay-Dee Hospital: Charles Lawton, MD; Janice D'Hulst, RRT. MetroHealth Medical Center of Cleveland: Joel R. Peerless, MD; Carolyn Smith, RN. San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center: Richard Kallet, MS, RRT; John M. Luce, MD. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital: Jonathan Gottlieb, MD; Pauline Park, MD; Aimee Girod, RN, BSN; Lisa Yannarell, RN, BSN. University of California San Francisco: Michael A. Matthay, MD*; Mark D. Eisner, MD, MPH; Brian Daniel, RCP, RRT. University of Colorado Health Sciences Center: Edward Abraham, MD*; Fran Piedalue, RRT; Rebecca Jagusch, RN; Paul Miller, MD; Robert McIntyre, MD; Kelley E. Greene, MD. University of Maryland: Henry J. Silverman, MD*; Carl Shanholtz, MD; Wanda Corral, BSN, RN. University of Michigan: Galen B. Toews, MD*; Deborah Arnoldi, MHSA; Robert H. Bartlett, MD; Ron Dechert, RRT; Charles Watts, MD. University of Pennsylvania: Paul N. Lanken, MD*; Harry Anderson, III, MD; Barbara Finkel, MSN, RN; C. William Hanson, III, MD. University of Utah Hospital: Richard Barton, MD; Mary Mone, RN. University of Washington/Harborview Medical Center: Leonard D. Hudson, MD*; Greg Carter, RRT; Claudette Lee Cooper, RN; Annemieke Hiemstra, RN; Ronald V. Maier, MD; Kenneth P. Steinberg, MD. Utah Valley Regional Medical Center: Tracy Hill, MD; Phil Thaut, RRT. Vanderbilt University: Arthur P. Wheeler, MD*; Gordon Bernard, MD*; Brian Christman, MD; Susan Bozeman, RN; Linda Collins; Teresa Swope, RN; Lorraine B. Ware, MD.

Clinical Coordinating Center. Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School: David A. Schoenfeld, PhD*; B. Taylor Thompson, MD; Marek Ancukiewicz, PhD; Douglas Hayden, MA; Francine Molay, MSW; Nancy Ringwood, BSN, RN; Gail Wenzlow, MSW, MPH; Ali S. Kazeroonin, BS.

NHLBI Staff. Dorothy B. Gail, PhD; Andrea Harabin, PhD*; Pamela Lew; Myron Waclawiw, PhD.

*Steering Committee. Gordon R. Bernard, MD, chair. Principal investigator from each center is indicated by an asterisk.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Roger G. Spragg, MD, chair; James Boyett, PhD; Jason Kelley, MD; Kenneth Leeper, MD; Marion Gray Secundy, PhD; Arthur Slutsky, MD.

Protocol Review Committee. Joe G.N. Garcia, MD, chair; Scott S. Emerson, MD, PhD; Susan K. Pingleton, MD; Michael D. Shasby, MD; William J. Sibbald, MD (posthumous).

Footnotes

See also p. 2431.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood KA, Huang D, Angus DC. Improving clinical trial design in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(Suppl 4):S305–S311. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057908.11686.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisner MD, Thompson T, Hudson LD, et al. Efficacy of low tidal volume ventilation in patients with different clinical risk factors for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:231–236. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2011093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton RD, Wang BM, Hudson LD, et al. Causes and timing of death in patients with ARDS. Chest. 2005;128:525–532. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson LD, Milberg JA, Anardi D, et al. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(2 Pt 1):293–301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estenssoro E, Dubin A, Laffaire E, et al. Incidence, clinical course, and outcome in 217 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2450–2456. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treggiari MM, Hudson LD, Martin DP, et al. Effect of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome on outcome in critically ill trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:327–331. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000108870.09693.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guidet B, Aegerter P, Gauzit R, et al. Incidence and impact of organ dysfunctions associated with sepsis. Chest. 2005;127:942–951. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: Results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:344–353. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194725.48928.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware LB. Prognostic determinants of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults: Impact on clinical trial design. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(Suppl 3):S217–S222. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000155788.39101.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flori HR, Ware LB, Glidden D, et al. Early elevation of plasma soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in pediatric acute lung injury identifies patients at increased risk of death and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4:315–321. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000074583.27727.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene KE, Ye S, Mason RJ, et al. Serum surfactant protein-A levels predict development of ARDS in at-risk patients. Chest. 1999;116(Suppl 1):90S–91S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin DB, Wiener-Kronish JP, Murray JF, et al. Elevated von Willebrand factor antigen is an early plasma predictor of acute lung injury in nonpulmonary sepsis syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:474–480. doi: 10.1172/JCI114733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss M, Gillespie MK, Ackerson L, et al. Endothelial cell activity varies in patients at risk for the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1782–1786. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware LB, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, et al. Significance of von Willebrand factor in septic and nonseptic patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:766–772. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1434OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, et al. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:327–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of lisofylline for early treatment of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Ketoconazole for early treatment of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons PE, Matthay MA, Ware LB, et al. Elevated plasma levels of soluble TNF receptors are associated with morbidity and mortality in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L426–L431. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00302.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000149854.61192.dc. discussion, 230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisner MD, Parsons P, Matthay MA, et al. Plasma surfactant protein levels and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Thorax. 2003;58:983–988. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.11.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware LB, Fang X, Matthay MA. Protein C and thrombomodulin in human acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L514–L521. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00442.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conner ER, Ware LB, Modin G, et al. Elevated pulmonary edema fluid concentrations of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients with acute lung injury: Biological and clinical significance. Chest. 1999;116(Suppl 1):83S–84S. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.83s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prabhakaran P, Ware LB, White KE, et al. Elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in pulmonary edema fluid are associated with mortality in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L20–L28. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619–1636. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vittinghoff E, Glidden D, Shiboski SC, et al. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures Models. Springer Science+Business Media; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orwoll ES, Bauer DC, Vogt TM, et al. Axial bone mass in older women. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:187–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, et al. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware LB, Conner ER, Matthay MA. Von Willebrand factor antigen is an independent marker of poor outcome in patients with early acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2325–2331. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ribes JA, Francis CW, Wagner DD. Fibrin induces release of von Willebrand factor from endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:117–123. doi: 10.1172/JCI112771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton KK, Sims PJ. Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ associated with von Willebrand factor release in human endothelial cells exposed to histamine. Study of microcarrier cell mono-layers using the fluorescent probe indo-1. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:600–608. doi: 10.1172/JCI112853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan T, Nielsen LD, Allen MJ, et al. Serum SP-D is a marker of lung injury in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L824–L832. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00421.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackay F, Loetscher H, Stueber D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-induced cell adhesion to human endothelial cells is under dominant control of one TNF receptor type, TNF-R55. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1277–1286. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernooy JH, Kucukaycan M, Jacobs JA, et al. Local and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors are increased in sputum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1218–1224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2202023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware L, Eisner MD, Wickersham N, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), a marker of impaired fibrinolysis, is associated with higher mortality in patients with ALI/ARDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberhard LW, Morabito DJ, Matthay MA, et al. Initial severity of metabolic acidosis predicts the development of acute lung injury in severely traumatized patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:125–131. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, et al. The injury severity score: A method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]