The crystal structure of human carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) complexed with acetazolamide (AZM) has been determined at 1.1 Å resolution. The co-binding of AZM and glycerol in the active site demonstrate that an isozyme specific CA inhibitor may be developed.

Keywords: human carbonic anhydrase II, acetazolamide, inhibitor design

Abstract

The crystal structure of human carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) complexed with the inhibitor acetazolamide (AZM) has been determined at 1.1 Å resolution and refined to an R cryst of 11.2% and an R free of 14.7%. As observed in previous CA II–inhibitor complexes, AZM binds directly to the zinc and makes several key interactions with active-site residues. The high-resolution data also showed a glycerol molecule adjacent to the AZM in the active site and two additional AZMs that are adventitiously bound on the surface of the enzyme. The co-binding of AZM and glycerol in the active site demonstrate that given an appropriate ring orientation and substituents, an isozyme-specific CA inhibitor may be developed.

1. Introduction

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are mainly zinc metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate. There are three genetically distinct families of CAs, the α-, β- and γ-classes, as well as the more recently discovered δ- and ∊-classes. The α-CAs are the only class that are present in mammals. There are 16 isoforms of α-CA in humans, 14 of which are expressed. Each isoform has a different catalytic activity, cellular localization and tissue distribution (Krishnamurthy et al., 2008 ▶).

Human carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) is the best characterized of the CAs. It is monomeric, with a molecular weight of ∼30 kDa, and is classified as an ultrafast enzyme, with a k cat/K m of 1.5 × 108 M −1 s−1 and a k cat of 1.4 × 106 s−1. The active-site zinc is tetrahedrally coordinated by three histidine residues and a H2O/OH− molecule. In the first step of the hydration reaction, the zinc-bound solvent, in the hydroxyl form, nucleophilically attacks the carbon of CO2, forming bicarbonate. The bicarbonate is then displaced by a water molecule, completing the first step of catalysis. In the second step, the zinc-bound water is regenerated into a hydroxyl by transfer of a proton through a series of intervening waters to His64 and bulk solvent (Krishnamurthy et al., 2008 ▶; Duda & McKenna, 2001 ▶).

CA II has been a drug target for decades. Therapeutic uses of CA inhibitors (CAIs) include the treatment of chronic diseases such as glaucoma and epilepsy. In glaucoma, CAIs act by reducing intraocular pressure (Katritzky et al., 1987 ▶). CAIs have also been used as a prophylactic treatment for altitude sickness in mountain climbers (Forwand et al., 1968 ▶). The most common class of CAIs are aromatic and heterocyclic sulfonamides [RSO2NH2 or RSO2NH(OH)]. The sulfonamides bind directly to the active-site zinc, displacing the H2O/OH− necessary for enzyme catalysis. One of the earliest and most frequently prescribed CAIs is acetazolamide (5-acetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-sulfonamide; AZM), marketed as Diamox, which has a K i of 10 nM for CA II (Breinin & Gortz, 1954 ▶).

The crystal structure of CA II was first determined in 1972 (Liljas et al., 1972 ▶). The Protein Data Bank (PDB; Berman et al., 2003 ▶) contains five CA II–AZM entries, which are all site-directed mutants [PDB codes 1yda, 1ydb, 1ydd (Nair et al., 1995 ▶), 1zsb (Huang et al., 1996 ▶) and 2h4n (Lesburg et al., 1997 ▶)]. The highest resolution reported for these entries is 1.9 Å.

Surprisingly, wild-type (wt) CA II complexed with AZM is conspicuous by its absence, although a brief report of a 1.9 Å resolution refinement has been published but not deposited in the PDB (Vidgren et al., 1990 ▶). Presented here is the refined crystal structure of wt CA II complexed with AZM at 1.1 Å resolution. Two additional molecules of AZM were identified bound to the surface of CA II, one in a site observed for other CAIs (Jude et al., 2006 ▶; Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶) and the other in a completely novel binding site. Additionally, a glycerol molecule was identified adjacent to the primary active-site AZM. The glycerol-binding site has previously been characterized at high resolution (Jude et al., 2006 ▶; Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶; Domsic et al., 2008 ▶); however, to our knowledge it has never been fully utilized in inhibitor development. Building on this observation, new isozyme-specific CAIs could be designed by branching into the glycerol-binding site.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Expression and purification

The expression and purification of wt CA II was performed as described previously in Fisher, Tu et al. (2007 ▶).

2.2. Crystallization and diffraction data collection

Crystals of CA II were grown as described in Fisher, Maupin et al. (2007 ▶). X-ray diffraction data were collected on Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) beamline A1 using an ADSC Quantum 210 detector at a wavelength of 0.997 Å. A cryoprotectant/AZM solution was made by mixing 5 µl 100 mM AZM solution in 50% DMSO with 20 µl glycerol and 80 µl precipitant solution. Crystals were immersed in cryoprotectant/AZM solution for 5–10 s and immediately flash-cooled at 100 K for data collection. A total of 300 frames, each with an oscillation range of 0.5° and an exposure of 10 s, were collected at a crystal-to-detector distance of 70 mm. The data frames were indexed, integrated and scaled with DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). Diffraction data statistics are presented in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Crystal data and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Crystal data | |

| Space group | Monoclinic P21 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 42.3, b = 41.2, c = 72.3, β = 104.1 |

| Molecules per ASU | 1 |

| VM (Å3 Da−1) | 2.09 |

| Solvent content (%) | 41.2 |

| Data collection | |

| Resolution (Å) | 23.4–1.1 (1.14–1.1) |

| Unique reflections | 92539 |

| No. of frames | 300 |

| Total No. of reflections | 162663 |

| Rmerge† (%) | 6.8 (39.0) |

| I/σ(I) | 13.8 (3.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.7 (96.0) |

| Mean multiplicity | 2.9 (2.5) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| No. of reflections used | 87911 |

| Rwork/Rfree‡ (%) | 11.2/14.7 |

| Reflections used for Rfree (|Fo| > 0) (%) | 5.0 |

| R.m.s. deviation, bonds (Å) | 0.014 |

| R.m.s. deviation, 1–3 distances (Å) | 0.030 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored | 89.8 |

| Allowed | 9.7 |

| Generously allowed | 0.5 |

| Model | |

| Protein atoms including alternate conformations | 2100 |

| Zn2+ | 1 |

| Glycerol (1) | 6 |

| AZM (3) | 39 |

| Waters, full/half occupancy | 348/56 |

| Average temperature factors (Å2) | |

| Main chain | 11.3 |

| Side chain | 15.7 |

| Waters (fully occupied only) | 32.0 |

| AZM 701/702/703 | 11.6/15.9/21.6 |

R

merge =

× 100, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual reflection and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average intensity.

× 100, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an individual reflection and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average intensity.

R

work =

× 100; R

free is identical to R

work but for 5% of data omitted from refinement.

× 100; R

free is identical to R

work but for 5% of data omitted from refinement.

2.3. Refinement of the model

Starting phases were calculated from PDB entry 2ili (Fisher, Maupin et al., 2007 ▶) with waters removed. Refinement using SHELXL from the SHELX-97 software package (Sheldrick, 2008 ▶) was alternated with manual refitting of the model in Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶). The final model has an R work of 11.2% and an R free of 14.7% and consists of one CA II chain, three AZMs, one glycerol and 348 fully occupied and 56 half-occupied water molecules. The quality of the final model was assessed by PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▶). Complete refinement statistics and model quality are included in Table 1 ▶.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. AZM interactions with CA II

The structure of CA II complexed with AZM (AZM 701) and two additional AZMs (702 and 703) bound at the enzyme surface has been determined to 1.1 Å resolution (Fig. 1 ▶). AZM 701 binds directly to the active site as described previously (Vidgren et al., 1990 ▶). This CA II–AZM structure differs from those previously published in the observation of two additional AZM molecules binding adventitiously at the surface of the enzyme, one in a site characterized for other CAIs and the other at a novel binding site. In addition, a glycerol molecule from the cryoprotectant solution binds adjacent to the heterocyclic ring of AZM 701 in the active site (Fig. 2 ▶).

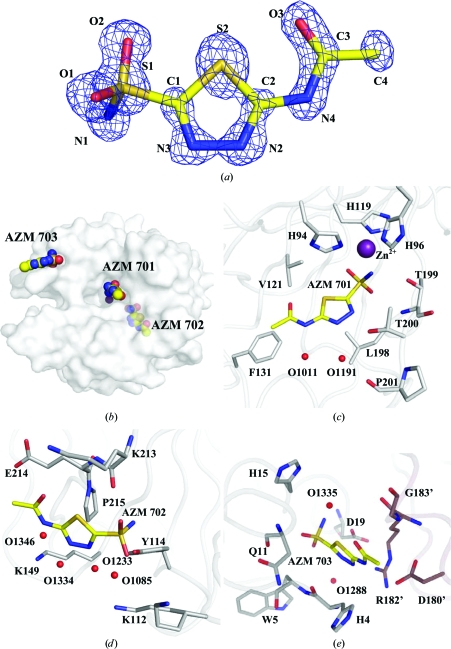

Figure 1.

AZM. (a) The 2|F o| − |F c| electron-density map (blue) for the active-site AZM 701, contoured at 2.2σ. (b) Semi-transparent surface of CA II, showing the locations of the three AZMs. AZM–CA II interactions are shown in (c) for AZM 701 (active site), (d) for AZM 702 and (e) for AZM 703. Protein C atoms are coloured gray, symmetry-related protein C atoms mauve, ligand C atoms yellow, N atoms blue, O atoms red, S atoms orange and Zn atoms purple. Waters are represented by red spheres. This figure was created using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

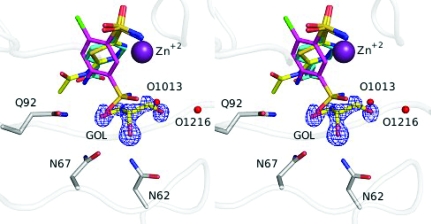

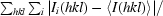

Figure 2.

Stereo image of a superposition of inhibitors and glycerol for 3hs4 (ligand C atoms in yellow, protein C atoms in gray; this work), 2pov (C atoms in magenta; Alterio et al., 2007 ▶) and 2nno (C atoms in cyan; Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶). The 2|F o| − |F c| electron-density map (blue) of glycerol (GOL) is contoured at 2.0σ. N atoms are coloured blue, O atoms red, S atoms orange, Cl atoms green and Zn atoms purple. Waters are represented by red spheres. This figure was created using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶).

The molecular geometry of the AZM ligand observed in this work is consistent with the small-molecule crystal structure. This includes the short O3–S2 nonbonded distance described by Vedani & Dunitz (1985 ▶). Additionally, despite a lack of interplanar restraints relating the acetamide group to the thiadiazole ring, the entire AZM molecule is nearly planar (Fig. 1 ▶ a).

Similar to other sulfonamide inhibitors of CA II, the sulfonamide amine N atom of AZM 701 binds directly to the active-site Zn atom along with the side chains of His94, His96 and His119. The overall Zn(N)4 coordination can be described as a distorted tetrahedron. Least-squares alignment of AZM 701 with the active-site AZMs of the five CAII mutant–AZM complex structures (listed in §1) shows nearly identical active-site orientations, with the exception being entry 1yda, an L198E mutant of CA II in which the sulfonamide geometry is distorted by lengthening of the Zn—N1 bond (Nair et al., 1995 ▶). The sulfonamide group forms a hydrogen bond to Thr199, the thiadiazole ring forms hydrogen bonds to Thr200 and water O1191 and the terminal acetamide group forms a hydrogen bond to water O1011. Additionally, O1191 bridges to Pro201 and Thr200. Hydrophobic interactions are primarily with Leu198, His94, Val121 and Phe131 (Fig. 1 ▶ c).

During the model adjustments between refinement cycles, two locations of residual electron density were noted which could be modeled as AZM 702 and AZM 703. They were both on the surface of the enzyme and were refined with fixed occupancies of 0.7 (Figs. 1 ▶ b, 1 ▶ d and 1 ▶ e).

AZM 702 lies in a shallow pocket on the surface of the enzyme opposite to that of the active site (Fig. 1 ▶ b). It is held in place by two hydrogen bonds to Tyr114 and Lys213. Numerous hydrophobic packing interactions also are present from the face of AZM to Lys213, Glu214 and Pro215. A string of water molecules (O1085, O1233, O1334 and O1346) links the AZM to hydrophilic side chains opposite the hydrophobic interactions, bridging to Lys112, Tyr114 and Lys149 (Fig. 1 ▶ d).

The second surface-bound AZM, AZM 703, is located near the N-terminus and is interposed between symmetry-related CA II molecules (Fig. 1 ▶ b). One face of AZM 703 lies along the main-chain atoms of Trp5 and His4. The other face contacts Arg182′, Asp180′ and Gly183′ of a symmetry-related molecule (designated by primes). The AZM is hydrogen bonded to His15, Asp19 and two water molecules (O1288 and O1335). Additionally, there are van der Waals interactions with His4 and Asn11 (Fig. 1 ▶ e). The position of AZM 703 was also occupied by inhibitors in seven other CA II crystal structures [2foq, 2fos, 2fou, 2fov (Jude et al., 2006 ▶), 2nno, 2nns and 2nnv (Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶)].

3.2. Glycerol interactions and implications for structure-based drug design

A glycerol molecule (GOL) from the cryoprotectant solution was observed in the active site, where it displaces several water molecules (Fig. 2 ▶). It is adjacent to the face of the AZM 701 ring and makes hydrogen-bond interactions with Asn62, Asn67, Gln92 and two water molecules: O1013 and O1216. Glycerol molecules have been seen at this position in several other high-resolution CA II structures, including 2fou (Jude et al., 2006 ▶), 3d92, 3d93 (Domsic et al., 2008 ▶), 2nno, 2nns and 2nnv (Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶).

The location of the glycerol molecule and its interactions with the CA II molecule also suggest a strategy for structure-aided drug design. Glycerol could be chemically linked with an inhibitor to impart not only specific hydrogen-bonding potential to the hydrophilic side of the active site, but also to improve the aqueous solubility of the inhibitor. Such an inhibitor might be one of the 6-chloro-benzene-1,3-disulfonamides [PDB codes 2pov (Fig. 2 ▶), 2pou, 2pow; Alterio et al., 2007 ▶]. In these structures, the aromatic ring of the inhibitors rotates ∼45° from the position observed in the crystal structures of AZM or benzene sulfonamides in CA II (PDB code 2nno; Srivastava et al., 2007 ▶). Glycerol or other hydrophilic fragments could be linked at the 3-position, replacing the free sulfonamide moiety. Given that Asn62 and Asn67 show significant variability between the different isoforms of CA (Duda & McKenna, 2001 ▶), future CAIs utilizing the glycerol-binding site might display isozyme specificity.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: carbonic anhydrase II, 3hs4, 3hs4sf

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff at CHESS for their help and support at the A1 station during X-ray data collection. This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant (GM25154) and a Maren Foundation grant.

References

- Alterio, V., De Simone, G., Monti, S. M., Scozzafava, A. & Supuran, C. T. (2007). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.17, 4201–4207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H., Henrick, K. & Nakamura, H. (2003). Nature Struct. Biol.10, 980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Breinin, G. M. & Gortz, H. (1954). AMA Arch. Ophthalmol.52, 333–348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. http://www.pymol.org.

- Domsic, J. F., Avvaru, B. S., Kim, C. U., Gruner, S. M., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Silverman, D. N. & McKenna, R. (2008). J. Biol. Chem.283, 30766–30771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duda, D. M. & McKenna, R. (2001). Handbook of Metalloproteins, edited by A. Messerschmidt, pp. 249–263. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S. Z., Maupin, C. M., Budayova-Spano, M., Govindasamy, L., Tu, C., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Silverman, D. N., Voth, G. A. & McKenna, R. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 2930–2937. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S. Z., Tu, C., Bhatt, D., Govindasamy, L., Agbandje-McKenna, M., McKenna, R. & Silverman, D. N. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 3803–3813. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forwand, S. A., Landowne, M., Follansbee, J. N. & Hansen, J. E. (1968). N. Engl. J. Med.279, 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. C., Lesburg, C. A., Kiefer, L. L., Fierke, C. A. & Christianson, D. W. (1996). Biochemistry, 35, 3439–3446. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jude, K. M., Banerjee, A. L., Haldar, M. K., Manokaran, S., Roy, B., Mallik, S., Srivastava, D. K. & Christianson, D. W. (2006). J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 3011–3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Katritzky, A. R., Caster, K. C., Maren, T. H., Conroy, C. W. & Bar-Ilan, A. (1987). J. Med. Chem.30, 2058–2062. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, V. M., Kaufman, G. K., Urbach, A. R., Gitlin, I., Gudiksen, K. L., Weibel, D. B. & Whitesides, G. M. (2008). Chem. Rev.108, 946–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Mol. Biol.231, 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lesburg, C. A., Huang, C., Christianson, D. W. & Fierke, C. A. (1997). Biochemistry, 36, 15780–15791. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liljas, A., Kannan, K. K., Bergsten, P. C., Waara, I., Fridborg, K., Strandberg, B., Carlbom, U., Jarup, L., Lovgren, S. & Petef, M. (1972). Nature New Biol.235, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nair, S. K., Krebs, J. F., Christianson, D. W. & Fierke, C. A. (1995). Biochemistry, 34, 3981–3989. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, D. K., Jude, K. M., Banerjee, A. L., Haldar, M., Manokaran, S., Kooren, J., Mallik, S. & Christianson, D. W. (2007). J. Am. Chem. Soc.129, 5528–5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vedani, A. & Dunitz, J. D. (1985). J. Am. Chem. Soc.107, 7653–7658.

- Vidgren, J., Liljas, A. & Walker, N. P. (1990). Int. J. Biol. Macromol.12, 342–344. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: carbonic anhydrase II, 3hs4, 3hs4sf

PDB reference: carbonic anhydrase II, 3hs4, 3hs4sf