Summary

Data collected in the years 2001–2003 from an antenatal clinic in Nairobi, Kenya, were used to assess the benefit of couple counselling and test it as a way of increasing the uptake of interventions in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Among 2833 women enrolled, 311 (11%) received couple pretest counselling and 2100 (74%) accepted HIV-1 testing. Among those tested 314 (15%) were HIV-1 seropositive. We incorporated these and other data from the cohort study into a spreadsheet-based model and costs associated with couple counselling were compared with individual counselling in a theoretical cohort of 10,000 women. Voluntary couple counselling and testing (VCT), although more expensive, averted a greater number of infant infections when compared with individual VCT. Cost per disability-adjusted life year was similar to that of individual VCT. Sensitivity analyses found that couple VCT was more cost-effective in scenarios with increased uptake of couple counselling and higher HIV-1 prevalence.

Keywords: cost effectiveness, couple VCT, DALY, HIV-1 prevention, mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, by 2004 an estimated 2,000,000 children were infected with HIV-1 via vertical transmission, the majority being from sub-Saharan Africa.1 Many of these infections may be prevented by effective implementation of simple interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV-1. These interventions involve HIV-1 counselling and testing during pregnancy with the administration of antiretrovirals, such as nevirapine, to prevent transmission. There is currently a hierarchy of approaches to HIV-1 voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) as part of PMTCT. An approach used in many settings is to provide pretest counselling to all pregnant women, after which women elect or ‘opt-in’ for HIV-1 testing. Following HIV-1 testing, all women receive post-test counselling, with seronegative women receiving risk-reduction counselling. The most intensive model of PMTCT HIV-1 VCT is to offer couple counselling and, in this model, the woman and her partner receive pre- and post-test counselling. In some studies, partner involvement has been associated with increased uptake of PMTCT interventions, making this an attractive option.2-8 It is therefore important to determine the cost effectiveness of couple counselling when compared with the conventional/standard method of offering antenatal VCT and critically evaluate its role in the prevention of infant HIV-1.

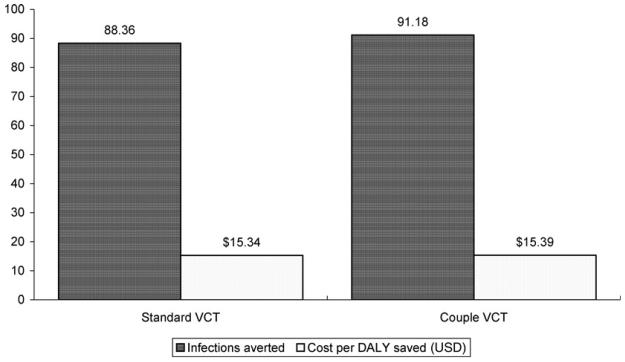

We conducted a study in Nairobi to assess the feasibility of couple counselling for PMTCT and to determine the effect of couple counselling on PMTCT intervention uptake. For this study, we obtained data on time and costs of individual and couple counselling. Using these data, we conducted cost effectiveness and sensitivity analyses to compare the two approaches to HIV-1 VCT in the antenatal setting: standard VCT and couple counselling with regard to cost and number of infant infections averted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cost per disability-adjusted life years saved and number of infant HIV-1 infections averted for standard versus voluntary couple counselling and testing (VCT)

METHODS

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and the University of Nairobi.

Development of the model using cohort study data

Data on HIV-1 prevalence, uptake of couple VCT, acceptance to testing, uptake of nevirapine, personnel costs and costs of supplies were obtained from a perinatal HIV-1 cohort study performed from 2001 to 2003 in Nairobi, Kenya. The study procedures and principle results of this study have been described elsewhere.2 Briefly, women attending their first antenatal visit were provided information as a group on HIV-1 infection and PMTCT interventions, and were then asked to return with their male partners after seven days for HIV-1 counselling and testing. Following pretest counselling, blood was collected for rapid HIV-1 testing on site and results were disclosed on the same day.

Duration of counselling time was recorded for each of the preand post-test counselling sessions. Mean time for a pre- and post-test counselling session was calculated and compared among women who received couple VCT and those who received individualized testing. Personnel costs were based on the average salaries of nurse counsellors and lab technicians and the time taken for group information, pre- and post-test counselling. Costs associated with the consumable equipment (e.g. test kits, vials, needles) used in the testing process were also included. Fixed expenditures such as rental costs and utilities were not included, as they would not differ between the options compared.

We assumed that the efficacy of nevirapine was similar to that observed in HIVNET 012 trial, specifically that the MTCT of HIV-1 rate was 14% among nevirapine users and 25% among non-users.6 For each option, we assumed equal rates of loss-to-follow up, acceptance of HIV-1 testing after counselling and receipt of results. Based on previous PMTCT studies in the same clinic, we assumed that without promoting couple VCT only 1% of the women would come with their partners.

Outcome measurements

Total costs associated with couple VCT and standard antenatal VCT were modelled. For each of the options our outcome measures were: (1) number of infant HIV-1 infections averted; (2) cost per infection averted; (3) number of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) saved and (4) cost per DALY saved. Outcomes and costs were based on data obtained from the cohort study described above and extrapolated to a hypothetical cohort of 10,000 women.

DALY was calculated using the formula given below:

There are five components of DALYs.

(1) Duration of time lost due to a death at each age is measured based on the life expectancy, which has been set at 51.5 years for women and 50 years for men.9

(2) Disability weights denote the degree of incapacity associated with various health conditions. Values range from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (death).

(3) Age-weighing function Cxe−βx indicates the relative importance of healthy life at different ages: where C, a constant = 0.16243; β, a constant = 0.04; x, age; e, a constant = 2.71.

(4) Discounting function (e−r(x−a)) indicates the value of health gains today when compared with the value of health gains in the future. Where r is the discount rate fixed at 0.03; a, onset of disease year; x, age; e, a constant = 2.71.

(5) Health is added across individuals – two people each losing 10 DALYs are treated as the same loss as one person losing 20 years.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the effect of modifying major variables on outcome measures. The variables targeted were HIV-1 prevalence (varied from 1% to 50%) and the rate of couple counselling uptake (varied from 0% to 100%).

RESULTS

Summary of study data in model

Among 2833 women enrolled, 2238 (79%) received pretest counselling and 311 (14%) of these were counselled as couples. Of all women tested for HIV-1, 314 (15%) were HIV-1 seropositive. Women receiving couple VCT were more likely to receive nevirapine than those counselled as individuals (84% vs. 62%, P = 0.013).

Programme costs were associated with health education, pretest counselling, laboratory technician time, laboratory supplies and post-test counselling. The cost of nurse counsellor time and laboratory technician time assumed a monthly salary of US$80 each for a 40-h workweek. Based on the personnel cost per minute, time (in minutes) per counselling session was used to calculate health education and counselling costs. In the study, average time for counselling was found to be as follows: group health education (15 min for an average group of eight women), individual pretest counselling (5.7 min), couple pretest counselling (9.9 min), individual post-test counselling for HIV-negatives (4.5 min), individual post-test for HIV-positives (12.3 min), couple post-test counselling for HIV-negatives (7.6 min), couple post-test counselling for HIV-positives (14.3 min).

Overall costs

The total programme cost was higher in the couple VCT approach (US$44,013) than in the standard approach (US$42,528). Using the average times and estimated salaries, the overall cost of providing pretest counselling services to 10,000 women was calculated as US$325.55 for group health education during pretest counselling, US$986 for individual pretest counselling and US$1715 for couple pretest counselling. The cost for post-test counselling for HIV-1-positive women was calculated as US$2144 if women were counselled alone and US$2483 if women were counselled with their partners (or US$0.20/woman and US$0.25/woman, respectively). Post-test counselling for HIV-1-negative women cost US$780 if women were counselled alone and US$1321 if counselled with their partners (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated costs of counselling and laboratory testing based on a prospective cohort

| Method | No. in group | Time per group (minutes) |

Cost per minute (US$) |

Cost per woman (US$) |

Cost per 10,000 women (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counselling costs | |||||

| Health education | |||||

| Whole group | 8 | 15.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 325.55 |

| Pretest counselling | |||||

| Individual | 1 | 5.68 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 986.19 |

| Couple | 1 | 9.88 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 1715.42 |

| Post-test counselling (HIV-positive) | |||||

| Individual | 1 | 12.35 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 2144.27 |

| Couple | 1 | 14.30 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 2482.84 |

| Post-test counselling (HIV-negative) | |||||

| Individual | 1 | 4.49 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 779.58 |

| Couple | 1 | 7.61 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 1321.29 |

| Method | Item/group | Quantity |

Cost per item (US$) |

Cost per woman (US$) |

Cost per 10,000 women (US$) |

| Laboratory costs | |||||

| Lab time | |||||

| Blood draw | 1 | 3 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 520.88 |

| Centrifuge | 8 | 10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 217.03 |

| Test | 8 | 20 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 434.06 |

| Recording | 1 | 2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 347.25 |

| Lab supplies | |||||

| – | Gloves | 50 | 5.00 | 0.10 | 1000.00 |

| – | Syringe | 100 | 37.50 | 0.38 | 3750.00 |

| – | Spirit | 5 | 6.00 | 1.20 | 12000.00 |

| – | Vacutainer needle | 100 | 15.00 | 0.15 | 1500.00 |

| – | Vacutainer bottle | 100 | 16.25 | 0.16 | 1625.00 |

| – | Swab | 20 | 1.25 | 0.06 | 625.00 |

| – | Strapping | 20 | 0.94 | 0.05 | 468.75 |

| – | HIV kit (capillus) | 100 | 275.00 | 2.75 | 27500.00 |

| Total lab costs | |||||

| HIV-negative | 5.00 | 49987.97 | |||

| HIV-positive | 7.75 | 77487.97 |

If 10,000 women were enrolled in each option, couple VCT had a higher number of women accepting HIV testing when compared with the standard option (7549 vs. 7508). Couple VCT had 91 infections averted and 2861 DALYs saved. This method had more infections averted and DALYs saved than was observed with the standard option (88 infections averted and 2772 DALYs saved) (Figure 1).

Sensitivity analysis

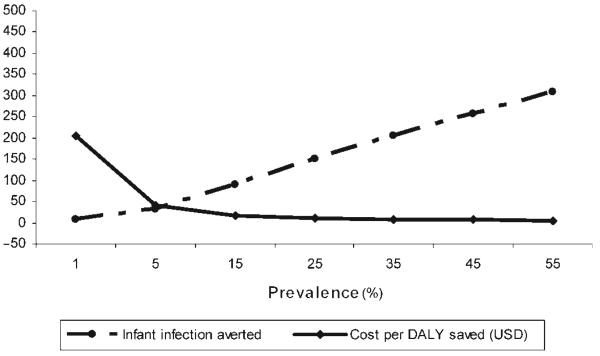

We performed a sensitivity analysis by varying the rate of acceptance of couple VCT (Figure 2) and HIV-1 seroprevalence (Figure 3). Figure 2 demonstrates that a 10% increase in the rate of couple VCT would lead to an increase of at least two infant infections averted. At the same time, the cost per DALY saved would increase by only a few cents because the proportionate increase in total cost was lower than the proportionate increase in the number of infant infections averted.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis for infant HIV-1 infections averted and cost per disability-adjusted life years (DALY) saved at various levels of couple voluntary counselling and testing rates. USD = US dollars

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis for infant HIV-1 infections averted and cost per disability-adjusted life years (DALY) saved at various levels of HIV-1 prevalence. USD = US dollars

In Figure 3, we show that in settings of higher HIV-1 prevalence the cost per DALY saved would decrease, and the number of infant infections averted would increase. Thus, it would be more cost-effective to set up a programme in Nairobi, where HIV-1 seroprevalence is 10–15% than it would be in central Kenya, where the antenatal HIV-1 seroprevalence is only 7%. However, it would be less cost-effective to set up a programme in Nairobi than it would be in Western Kenya, where the HIV-1 seroprevalence is higher at 35%.

DISCUSSION

This analysis found that it is possible to avert an infant infection at lower than US$483 using any of the two VCT options explored in this study. Couple counselling resulted in the greatest increase in the total programme cost; however, this approach also averted more infant infections. As a result, the cost per infection averted was approximately the same and the cost per DALY saved was also the same as that of the standard antenatal VCT.

In addition, couple counselling has benefits other than those examined in this analysis that are indirectly related to PMTCT because they impact heterosexual HIV-1 transmission. Testing of men that occurs as a result of couple counselling may allow couples in which the female partner is HIV-1 seronegative to prevent acute HIV-1 acquisition during late pregnancy or breastfeeding. Sexual behaviour may also be modified in couples learning that they are concordantly HIV-1 seronegative.

From our sensitivity analysis, we learned that the cost per infection averted decreased with higher rates of male partner participation. There is a need to find out the reasons for low partner involvement in PMTCT and efforts need to be made to increase couple counselling in antenatal VCT as well as in other sites. Men may be unwilling to accompany their female partners to the antenatal clinic making it worthwhile to explore other venues for couple testing or make antenatal clinics more accommodating to male clients.

Finally, we found that the cost per infection averted was lower in the high HIV-1 prevalence areas, which suggests that couple counselling would be more cost-effective in those regions severely hit by the AIDS epidemic. In areas of Western Kenya and Southern Africa where more than 30% of pregnant women test HIV-1 seropositive the cost per DALY would be the lowest and couple VCT would be the most cost-effective.

In conclusion, in cost-effectiveness model based on data collected in a large perinatal HIV-1 transmission cohort, that included couple counselling for VCT, we demonstrate that couple counselling could be cost-effective and could avert more infant HIV-1 infections than standard VCT. Overcoming the challenges of incorporating men and couple counselling into antenatal settings would be beneficial in the long run and worth the investment in resources, time and effort.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by the International AIDS Research and Training Programme through several grants from National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations Development Programme . Cultural Liberty in Today's Diverse World. UN; New York: 2004. Human Development Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, et al. Antenatal couple counselling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1620–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creese A, Floyd K, Alban A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV/AIDS interventions in Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. Lancet. 2002;359:1635–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweat M, Gregorich S, Sangiwa G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in reducing sexual transmission of HIV-1 in Kenya and Tanzania. Lancet. 2000;356:113–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forsythe S, Arthur G, Ngatia, Mutemi R, Odhiabo J, Gilks C. Assessing the cost and willingness to pay for voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in Kenya. AIDS Alert. 1998;13:107–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiarie JN, Kreiss JK, Richardson BA, et al. Compliance with antiretroviral regimens to prevent perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Kenya. AIDS. 2003;17:65–71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000042938.55529.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marjan RS, Ruminjo JK. Attitudes to prenatal testing and notification for HIV-1 infection in Nairobi, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:665–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farquhar C, Mbori-Ngacha DA, Bosive RK, et al. Partner notification by HIV-1 seropositive pregnant women: association with infant feeding decisions. AIDS. 2001;15:815–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics Kenya Demographic Health Survey. 2003 www.cbs.go.ke.