Abstract

Context

Prolongation of the electrocardiographic PR interval, known as first-degree atrioventricular block when the PR exceeds 200 milliseconds, is frequently encountered in clinical practice.

Objective

To determine the clinical significance of PR prolongation in ambulatory individuals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective, community-based cohort in Framingham, MA. We studied 7,575 individuals (mean age 46 years, 54% women) who underwent routine 12-lead electrocardiography. The study cohort was followed prospectively from baseline examinations in 1968–1974 through 2007. We used multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models to examine the relations of PR interval with the incidence of arrhythmic events and death.

Main Outcome Measures

Incident atrial fibrillation (AF), pacemaker implantation, and all-cause mortality.

Results

During follow up, 481 participants developed AF, 124 required pacemaker implantation, and 1,739 died. At the baseline examination, 124 individuals had PR >200 milliseconds. Incidence rates per 10,000 person-years for those with PR >200 milliseconds compared to those with PR ≤200 milliseconds were 140 (95% confidence interval [CI], 95–208) versus 36 (95% CI, 32–39) for AF, 59 (95% CI, 40–87) versus 6 (95% CI, 5–7) for pacemaker implantation, and 333 (95%, CI 260–428) versus 129 (95% CI, 123–135) for death. Corresponding absolute risk increases were 1.04% (AF), 0.53% (pacemaker), and 2.05% (death) per year. In multivariable analyses, each 20-millisecond increment in PR was associated with an adjusted hazards ratio (HR) of 1.12 (95% CI, 1.02–1.22; p=0.018) for AF, 1.22 (95% CI, 1.14–1.30; p<0.001) for pacemaker implantation, and 1.08 (95% CI, 1.02–1.13; p=0.005) for death. Individuals with first-degree atrioventricular block had a two-fold adjusted risk of AF (HR 2.06; 95% CI, 1.36–3.12; p<0.001), three-fold adjusted risk of pacemaker implantation (HR 2.89; 95% CI, 1.83–4.57; p<0.001), and 1.4-fold adjusted risk of death (HR 1.44, 95% C,I 1.09–1.91; p=0.01).

Conclusion

PR prolongation is associated with increased risks of AF, pacemaker implantation, and death.

BACKGROUND

Prolongation of the electrocardiographic PR interval, conventionally known as first-degree atrioventricular block (AVB) when the PR exceeds 200 milliseconds, is frequently encountered in clinical practice.1–4 The PR interval is determined by the conduction time from the sinus node to the ventricles and thus integrates information about a number of sites in the conduction system of the heart. First-degree AVB may result from conduction delay in the atrium, atrioventricular node, and/or His-Purkinje system. The atrioventricular node is the most commonly involved site in adults, although more than one site of conduction delay is often present.5

The known causes of first-degree AVB are numerous and include ischemic heart disease, degenerative conduction system disease, congenital heart disease, connective tissue disease, inflammatory diseases, and medications. However, in ambulatory individuals, first-degree AVB typically occurs in the absence of acute cardiovascular disease.1, 4 The clinical significance of first-degree AVB in this setting is unclear. Several prior studies suggest that first-degree AVB has a benign prognosis, although these studies were based on young, healthy men in the military.1, 6 Data from more representative cohorts are limited, although one study in middle-aged men suggested that first-degree AVB may be associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease.2

To investigate the prognosis associated with first-degree AVB, we prospectively examined the relations of electrocardiographic PR interval with arrhythmic events and mortality in the community-based Framingham Heart Study. Advantages of this study population include its large size, inclusion of both sexes, use of a reproducible ECG measurement protocol, and the availability of multiple decades of follow up.

METHODS

Study Sample

The design and selection criteria of the Original and Offspring cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study have been described previously.7, 8 The baseline examinations for the present investigation were the 11th biennial examination of the Original cohort (1968–1971; n=2,955 attendees) and the 1st Offspring cohort examination (1971–1974; n=5,124). Of the 8,079 attendees at the index examinations, we excluded 504 individuals (6.7%) for the following reasons, in hierarchical fashion: inadequate ECG for measurement of PR interval (n=81), age <20 years (n=243), history of atrial fibrillation (AF) or prevalent AF at the examination (n=29), use of antiarrhythmic agents or cardiac glycosides or a history of pacemaker implantation (n=86), and missing covariates (n=65). After these exclusions, 7,575 participants (4,089 women) remained eligible. All participants gave written informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston University Medical Center.

Examination and Electrocardiography

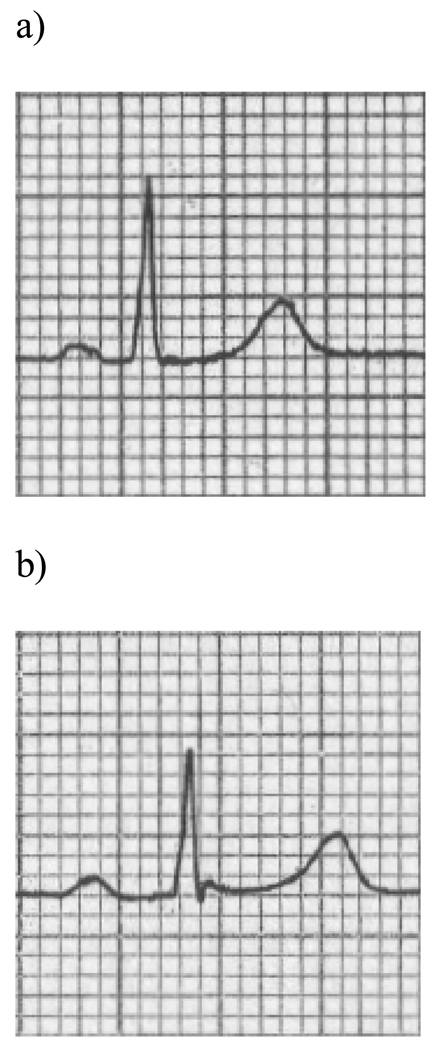

All attendees underwent a routine physical examination, anthropometry, standard 12-lead electrocardiography recorded at a paper speed of 25 mm/sec, and laboratory assessment of cardiovascular disease risk factors. At the 11th Original cohort examination and 1st Offspring cohort examination, electrocardiographic measurements were made digitally by eResearchTechnology, Inc. (previously known as Premier Worldwide Diagnostics, Ltd,). The PR intervals were measured to the nearest millisecond by trained technicians using digital calipers and a magnifying tablet. A single lead (lead II) was used and two measurements were averaged with a mean coefficient of variation of 3.9%. The PR interval was defined as the interval from the onset of the P wave (junction between the T–P isoelectric line and the beginning of the P wave deflection) to the end of the PR segment (junction with the QRS complex) (Figure 1). At subsequent examinations of the Original cohort (every 2 years) and Offspring cohort (approximately every 4 years), 12-lead electrocardiography was repeated, and intervals were measured by physician investigators.

Figure 1.

Representative examples of (a) a normal PR interval and (b) a prolonged PR interval detected by routine electrocardiography in the study sample.

Follow Up and Outcome Events

All Framingham Heart Study participants are under surveillance for death and cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, stroke, and heart failure), as detailed elsewhere.9 Additionally, we routinely ascertain information on 2 arrhythmia-related endpoints: AF and pacemaker implantation. Information about cardiovascular and arrhythmic events was obtained by review of medical histories, physical examinations at the Framingham Heart Study, and hospitalization and personal physician records, including electrocardiograms. A panel of 3 experienced investigators reviewed pertinent medical records for all suspected new events. A cardiologist evaluated all electrocardiograms with suspected AF or atrial flutter. A diagnosis of AF was made when the following electrocardiographic features were noted: absence of P waves, presence of coarse or fine fibrillatory waves, and irregular RR intervals. Atrial flutter was defined according to standard criteria10 and combined with AF in all analyses.

Statistical Analyses

We constructed multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine the relations of the PR interval to the occurrence of arrhythmic events and death on follow up. All models were stratified by sex and prevalent cardiovascular disease status (indicated by a history of myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, stroke, or heart failure). Follow up was censored after 20 years in order to reduce the influence of competing risk factors. We then tested for proportionality of hazards for each endpoint (AF, pacemaker implantation, and death) by fitting a multiplicative interaction term of follow-up time and PR interval. Proportionality of hazards was confirmed for AF and death but not for pacemaker implantation. Therefore, we used a single, 20-year follow-up period in the longitudinal analyses of AF and death as endpoints.

For the endpoint of pacemaker implantation, we used the method of pooling repeated observations11 to assess the prediction of pacemaker events over consecutive 12-year intervals, a period over which the hazards of pacemaker placement were proportional. Cox models were constructed for each 12-year follow-up interval, and participants became eligible to re-enter the analyses if they remained free of events and met the exclusion criteria at each index visit. Original and Offspring cohort participants attended a total of 17,206 person-examinations during up to 35 years of follow-up. In analyses of incident pacemaker implantation only, we used the physician-coded PR interval, rather than the interval measured from the digital calipers, because the latter was only available at a single set of examinations.

We analyzed the PR interval first as a continuous variable, and then as a categorical variable, using the clinical definition of first-degree AVB (PR >200 milliseconds). In the multivariable models, we adjusted for age, heart rate, hypertension, body mass index, total/HDL cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes. For the AF analysis, we included the following additional covariates: valve disease (≥3/6 systolic murmur, or any diastolic murmur; yes/no), electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy,12 and presence or absence of atrial premature beats on a 10-second rhythm strip.13–15 Additional adjustment for QRS interval was performed for models of time to pacemaker implantation.

Because beta-blockers and calcium-channel blockers can affect cardiac conduction times, we performed analyses with and without participants taking these nodal-blocking medications at baseline (concurrent with the PR interval measurement). For the pacemaker analyses, this exclusion was applied at the beginning of every 12-year follow-up interval. For the AF and death analyses, we accounted for use of beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers subsequent to the baseline examination by incorporating time-dependent covariates in secondary analyses.

Secondary analyses were also performed excluding participants with QRS interval ≥120 milliseconds, adjusting for interim myocardial infarction or heart failure as time dependent covariates, and censoring participants with baseline or subsequent myocardial infarction or heart failure at the time of development of the event. Because right ventricular pacing has been associated with incident AF,16 we also performed analyses adjusting for interim pacemaker placement as a time dependent covariate in models predicting AF. Lastly, we assessed whether PR prolongation predicted future coronary heart disease events, defined as myocardial infarction or coronary insufficiency.2

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC),17 and a two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Baseline characteristics of the 7,575 study participants (mean age 46 years; 54% women) are shown in Table 1. One third of individuals had hypertension, and only 2% had a previous history of myocardial infarction or heart failure. The median PR interval was 149 milliseconds, and 124 participants had PR >200 milliseconds at the baseline examination.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Characteristic | Whole Sample (N=7,575) |

Baseline PR ≤200 milliseconds (N=7,451) |

Baseline PR >200 milliseconds (N=124) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 46 ± 15 | 46 ± 15 | 55 ± 16 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 4089 (54) | 4055 (54) | 34 (27) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.8 ± 4.3 | 25.8 ± 4.3 | 26.6 ± 3.4 |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | 3417 (45) | 3365 (45) | 52 (42) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2462 (33) | 2409 (32) | 53 (43) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 661 (9) | 637 (9) | 24 (19) |

| Total/HDL cholesterol ratio | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 1.7 |

| Valve disease, n (%) | 432 (6) | 418 (6) | 14 (11) |

| Prior MI or CHF, n (%) | 169 (2) | 157 (2) | 12 (10) |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 76 ± 14 | 76 ± 14 | 65 ± 12 |

| ECG-LVH, n (%) | 69 (1) | 67 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Atrial premature beats, n (%) | 76 (1) | 75 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Mean QRS, milliseconds | 87 ± 10 | 87 ± 10 | 93 ± 16 |

| Mean PR, milliseconds | 151 ± 20 | 150 ± 19 | 216 ± 15 |

| Median PR, milliseconds | 149 | 149 | 211 |

Values shown are mean ± SD, medians, or numbers (percents). CHF, congestive heart failure; ECG-LVH, electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy; MI, myocardial infarction. The presence of atrial premature beats is defined based on a 10-second rhythm strip.

PR Prolongation and Incident Events

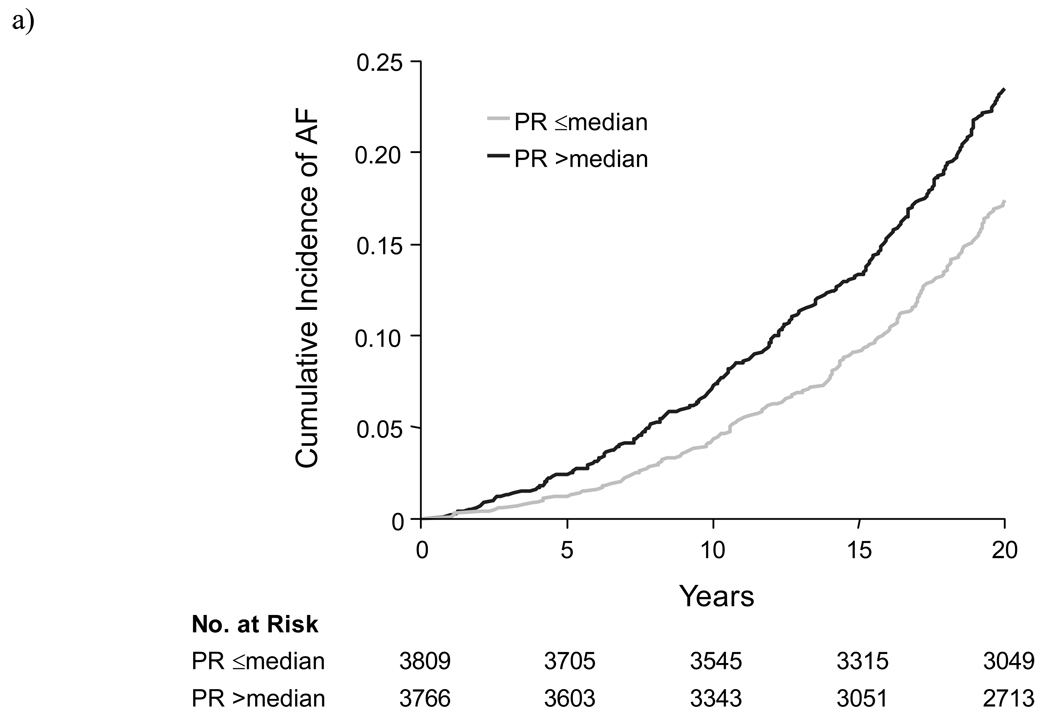

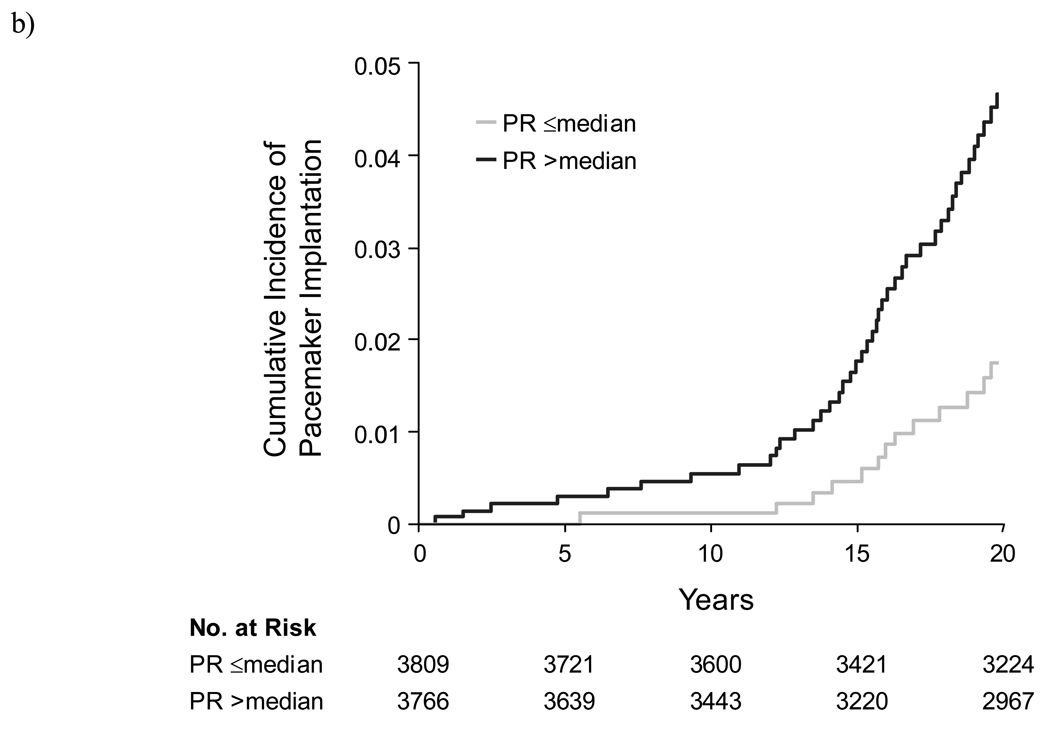

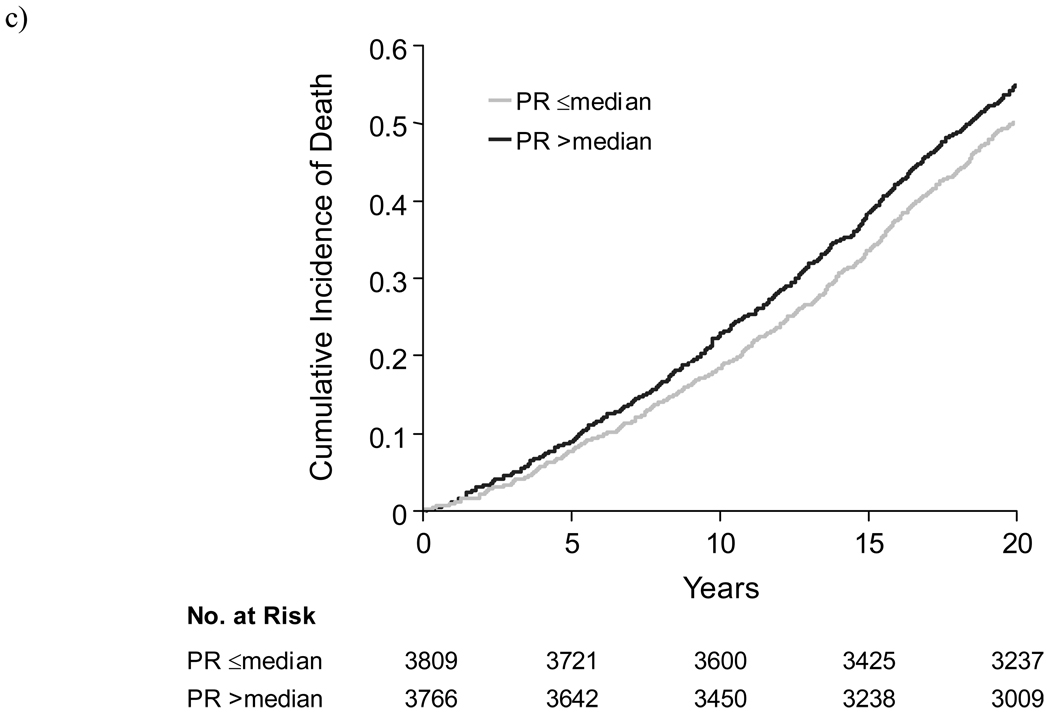

During the follow-up period, 481 participants developed AF, 124 participants had implantation of a pacemaker, and 1,739 participants died. Among 102 individuals in whom the indication for pacemaker placement was documented, 36% were for high-grade AVB and 53% were for sinus node dysfunction. The cumulative incidence of arrhythmic and mortality events, according to the baseline PR interval, is shown in Figure 2. Crude incidence rates of AF, pacemaker implantation, and death among participants with a baseline PR >200 milliseconds, compared to those with PR ≤200 milliseconds, are shown in Table 2. Individuals with baseline first-degree AVB, compared to those with a normal PR interval, had unadjusted hazards ratios of 4.26 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.85–6.38) for AF (absolute risk increase [ARI] 1.04% per person year), 10.26 (95% CI, 6.67–15.82) for pacemaker placement (ARI 0.53%), and 2.72 (95% CI, 2.11–3.51) for death (ARI 2.05%) (Table 3). Based on the absolute risk increases for the outcomes associated with PR prolongation, the numbers needed to harm were 96 for AF, 189 for pacemaker, and 49 for death.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the cumulative unadjusted incidence of (a) atrial fibrillation, (b) pacemaker implantation, and (c) death, among individuals with baseline PR interval above or below the median (149 milliseconds).

Table 2.

Incidence of Death, Atrial Fibrillation, and Pacemaker Implantation

| Incidence Rate, per 10,000 person years | ||

|---|---|---|

| PR ≤200 milliseconds | PR >200 milliseconds | |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 36 (32–39) | 140 (95–208) |

| Pacemaker | 6 (5–7) | 59 (40–87) |

| Death | 129 (123–135) | 333 (260–428) |

Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. Among individuals with PR ≤200 milliseconds 456 individuals developed atrial fibrillation, 98 required pacemaker implantation, and 1,677 died; among individuals with PR >200 milliseconds, 25 individuals developed atrial fibrillation, 26 required pacemaker implantation, and 62 died. Data for pacemaker implantation are based on pooled observations from sequential 12-year follow-up periods.

Table 3.

PR interval and Risks of Death, Atrial Fibrillation, and Pacemaker Implantation

| Whole Sample Hazards Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Persons Not on Nodal-Blocking Agents Hazards Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Unadjusted | P-value | Multivariable- adjusted |

P-value | Unadjusted | P-value | Multivariable- adjusted |

P-value |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

1.38 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.02 | 1.39 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.02 |

| (1.27–1.50) | (1.02–1.22) | (1.28–1.52) | (1.02–1.23) | |||||

|

Pacemaker implantation |

1.43 | <0.001 | 1.22 | <0.001 | 1.88 | <0.001 | 1.37 | <0.001 |

| (1.37–1.50) | (1.14–1.30) | (1.68–2.09) | (1.20–1.57) | |||||

| Death | 1.27 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.005 | 1.27 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.008 |

| (1.22–1.33) | (1.02–1.13) | (1.21–1.34) | (1.02–1.14) | |||||

Number of events in the sample included 481 for AF, 124 for pacemaker implantation, and 1,739 for death. Hazards ratios represent risk per SD increment in PR interval. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. All models are stratified by sex and cardiovascular disease status, and further adjusted for age, heart rate, body mass index, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and total/HDL cholesterol. For AF analyses, additional covariates included atrial premature beats, valve disease, ECG LVH. For pacemaker analyses, QRS duration was included as an additional covariate.

Multivariable Analyses

Table 3 displays the results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for PR interval. After adjustment for conventional risk factors, the PR interval was a significant predictor of all three outcomes. Each standard deviation increment in the PR interval (20 milliseconds) was associated with adjusted hazards ratios of 1.12 (95% CI, 1.02–1.22; p=0.02) for AF, 1.22 (95% CI, 1.14–1.30; p<0.001) for pacemaker implantation, and 1.08 (95% CI, 1.02–1.13; p=0.005) for death. Similar results were observed when individuals on nodal-blocking medications were excluded from the analyses.

Analyses were repeated using the clinical definition of first-degree AVB (PR >200 versus ≤200 milliseconds) (Table 4). Defined in this manner, PR prolongation was associated with multivariable-adjusted hazards ratios of 2.06 (95% CI, 1.36–3.12; p<0.001) for AF, 2.89 (95% CI, 1.83–4.57; p<0.001) for pacemaker implantation, and 1.44 (95% CI, 1.09–1.91; p=0.01) for death.

Table 4.

First-Degree AVB and Risks of Death, Atrial Fibrillation, and Pacemaker Implantation

| Whole Sample Hazards Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

Persons Not on Nodal-Blocking Agents Hazards Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Unadjusted | P-value | Multivariable- adjusted |

P-value | Unadjusted | P-value | Multivariable- adjusted |

P-value |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

4.26 | <0.001 | 2.06 | <0.001 | 4.91 | <0.001 | 2.36 | <0.001 |

| (2.85–6.38) | (1.36–3.12) | (3.23–7.48) | (1.53–3.64) | |||||

|

Pacemaker implantation |

10.26 | <0.001 | 2.89 | <0.001 | 13.30 | <0.001 | 4.32 | <0.001 |

| (6.67–15.82) | (1.83–4.57) | (7.76–22.80) | (2.46–7.59) | |||||

| Death | 2.72 | <0.001 | 1.44 | 0.01 | 2.86 | <0.001 | 1.48 | 0.01 |

| (2.11–3.51) | (1.09–1.91) | (2.18–3.76) | (1.10–2.00) | |||||

Number of events in the sample included 481 for AF, 124 for pacemaker implantation, and 1,739 for death. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. All models are stratified by sex and cardiovascular disease status, and further adjusted for age, heart rate, body mass index, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and total/HDL cholesterol. For AF analyses, additional covariates included atrial premature beats, valve disease, ECG LVH. For pacemaker analyses, QRS duration was included as an additional covariate.

Secondary Analyses

Results were unchanged in secondary analyses for each endpoint that excluded individuals with QRS ≥120 milliseconds. Additionally, there was no evidence for a sex interaction with PR for any of the outcomes (Pinteraction>0.2). There was also no significant change in outcomes or risk estimates when analyses were stratified by Original versus Offspring cohort.

Because myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pacemaker implantation could be predisposing factors for AF, we repeated the analyses for AF with adjustment for these interim events; the association with PR interval remained significant. Similarly, adjustment for interim myocardial infarction or heart failure in the cross-sectional pooling analyses did not attenuate the relation between PR interval and risk of pacemaker placement. The relation of PR with incident AF and death remained significant after adjusting for exposure to nodal-blocking medications as a time-dependent covariate.

The relation between prolonged PR and all three outcomes remained significant after excluding individuals with prevalent myocardial infarction or heart failure at baseline and censoring those developing these events during follow up. Furthermore, there was no relation between baseline PR and incidence of coronary heart disease events in multivariable-adjusted analyses.

Progression of Conduction Disease

Among subjects with first-degree AVB at the initial examination (n=124), a majority returned to at least one subsequent examination and had an interpretable follow-up ECG (n=98). Of this group, 13 developed further PR interval prolongation (increase by >40 msec) and 26 developed higher-grade conduction abnormalities (4 with second-degree AVB, 14 with incomplete bundle-branch block, and 8 with complete bundle-branch block).

Among individuals with a normal PR interval at the baseline examination, 161 (3%) developed first-degree AVB by the follow-up examination 12 years later. These individuals had higher multivariable-adjusted hazards for AF (hazards ratio 1.53; 95% CI, 1.05–2.24; P=0.028) and pacemaker implantation (hazards ratio 2.65; 95% CI, 1.60–4.37; P=0.0001), but not death.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our results suggest that individuals with first-degree AVB are at a substantially increased risk of future AF (~two-fold) and pacemaker implantation (~three-fold), and a moderately increased risk of death, compared to individuals without first-degree AVB. The validity of these findings is supported by the large, community-based sample, the routine surveillance of all participants for cardiovascular outcomes, and the long period of follow up.

These observations challenge the longstanding perception that PR interval prolongation or first degree AVB has a benign prognosis.1, 3, 4, 6, 18 Notably, previous longitudinal studies relating PR interval to prognosis have been almost exclusively restricted to young or middle-aged men,1, 3, 4, 6 with the two largest studies based on healthy air force pilots recruited in the World War II era.1, 6 A subsequent study based on several international cohorts (Seven Countries Study) found an association between first-degree AVB and coronary heart disease, but with very few incident events and using unadjusted analyses.2 The present study is the first investigation based on a contemporary, community-based cohort, with standardized assessment of baseline risk factors and outcomes, including arrhythmic endpoints.

Although PR prolongation can occur in association with overt cardiovascular disease, residual confounding by prevalent cardiovascular disease is an unlikely explanation for our findings. Participants who attended the routine Framingham Heart Study examinations were generally healthy, and the proportion with existing cardiovascular diagnoses or treatment with medications known to affect the conduction system was extremely low. The results were not changed by exclusion of people with prevalent cardiovascular disease, nor by comprehensive adjustment for risk factors and interim cardiovascular events. In addition, the excess hazard associated with prolonged PR was strongest for arrhythmic events (AF and pacemaker implantation), which provides further support for the specificity of our findings.

There are several potential explanations for the observed association of a longer PR interval with adverse outcomes. Chronic PR prolongation could be a precursor to more severe degrees of conduction block. Because there are few “hard” clinical endpoints related to the conduction system, we examined the rate of pacemaker implantation as a surrogate for advanced conduction system disease. The risk of pacemaker implantation was strongly associated with the PR interval, despite adjustment for age, cardiovascular risk factors, and QRS interval. Although Mymin and colleagues reported a low incidence of second- and third-degree AVB in young air force pilots with first degree AVB,6 the generalizability of their sample to unselected populations is uncertain. Air force pilots may be similar to conditioned athletes, in whom first degree AVB is caused by enhanced vagal tone19, 20 and typically disappears on long-term follow up.21

Alternately, PR prolongation could be a marker of other changes in the cardiovascular system that contribute to a worse prognosis or represent advanced “physiologic” age. Both autonomic and structural cardiac abnormalities may lead to prolongation of the PR interval.22 For instance, responses to catecholaminergic or inotropic stimuli are blunted with advanced age.23, 24 Fibrosis and calcification of the cardiac skeleton after age 40 was described by Lev,22, 25 and an early electrocardiographic manifestation may be PR prolongation. As such, the observed association between PR interval with mortality may be related to progressive alterations in the conduction system and/or cardiac structure.

Other potential explanations may specifically account for the association of longer PR interval with AF risk. Although first-degree AVB usually involves conduction delay in the atrioventricular node, it is frequently accompanied by abnormalities in other parts of the conduction system as well. Prior studies have raised the possibility that slowed intra-atrial or inter-atrial conduction may directly increase the risk of AF,26–31 and increased atrial conduction time or intra-atrial block may be manifested by prolongation of the PR interval. In addition, a prolonged PR interval results in delayed and ineffective mitral valve closure and diastolic mitral regurgitation,32 especially when the PR interval exceeds 230 milliseconds.33 An association between continuous PR interval and AF risk has been reported in a separate study using Framingham data to construct a clinical risk score for AF.34 The current study extends this observation by examining a longer follow-up interval, quantifying the risk associated with first-degree AVB, and demonstrating that the association is not attributable to interim cardiovascular events, pacemaker implantation, or use of nodal agents. Further research is warranted to investigate the possible mechanisms underlying the relation of PR prolongation with AF.

Several limitations of our study merit comment. The PR interval shows a circadian variation35 and may change over time.6 However, such misclassification would likely be random and would result in a conservative bias. Furthermore, study participants typically underwent electrocardiography in the morning upon arrival at the clinic. Investigators have also reported that longitudinal changes in individuals with a prolonged PR interval are typically small (<0.04 seconds).4 Median PR, QRS, and RR intervals in our study were somewhat shorter than those reported recently in another large ambulatory cohort.36 These differences could be due to the fact that manual measurements of paper recordings may deliver shorter electrocardiographic interval values compared with computerized algorithms used to assess digital recordings. Thus, modern cut-points for determining first-degree AVB could be slightly longer than what was used for this analysis. Also, the somewhat higher heart rate in the Framingham participants could be the result of shorter supine rest periods prior to ECG acquisition, compared with the prior report which was based on subjects enrolled in pharmaceutical trials. The Framingham protocol should more closely approximate what is done in clinical practice.

The proportion of individuals with baseline first-degree AVB who have progression of ECG conduction system abnormalities may be an underestimate, because subjects who did not return to follow-up examinations could have had a higher incidence of conduction disease progression. Although congenital abnormalities such as ostium primum atrial septal defects can cause PR lengthening, the extremely low prevalence of such disorders in the community suggests that they are unlikely to contribute to our findings. Prolongation of the PR interval may be due to delayed conduction at different of locations in the upper and lower conduction system, and as a result of different underlying pathologies. Since the PR interval was measured from the surface electrocardiogram, as opposed to an intracardiac recording, the relative contributions of delay at different conduction sites could not be assessed. As well, we did not have a measure of sinus node function apart from the heart rate, which we adjusted for in all of the multivariable analyses. The small number of individuals with first-degree AVB in the setting of nodal-blocking medications prevented us from specifically examining medication-related PR prolongation. Indeed, the association of PR prolongation with adverse outcomes in untreated individuals does not imply that PR prolongation from nodal blockade leads to increased risk.

Our analyses of pacemaker implantation were based on multiple index examinations to maintain proportionality of the hazards. For these analyses, we used the physician-coded PR interval rather than the PR measured using digital calipers. Reduced measurement precision would likely bias the association of PR interval with pacemaker placement toward the null. Furthermore, the physician-coded PR most closely approximates what is done in standard clinical practice.

For AF analyses, we were unable to adjust for alcohol exposure or incident thyroid disease, because data regarding these variables were not consistently obtained during the study period. The presence of valvular disease was based on murmurs detected by physical examination, since echocardiograms were not consistently available at the baseline examinations. Severe valvular disease is rare in the Framingham cohort.37 We focused on all-cause mortality, because adjudication of cardiovascular or sudden death in our cohort does not distinguish between arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic causes. Although there was no evidence for effect modification by sex in analyses using a sex-interaction term, we cannot exclude the possibility of such an interaction. Lastly, our sample was predominantly white, potentially limiting the applicability of our results to other racial/ethnic groups.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that individuals with PR interval prolongation have an elevated risk of future AF, need for pacemaker implantation, and death. These results suggest that the natural history of first-degree AVB is not as benign as previously believed. Additional studies are needed to determine appropriate follow up for individuals found to have PR prolongation on a routine electrocardiogram.

Acknowledgements

Funding Support

The Framingham Heart Study is funded by National Institutes of Health contract N01-HC-25195. Dr Vasan was supported in part by grant K24-HL-04334.

Role of the Sponsor

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute had no role in the study design, analyses, or drafting of the manuscript. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reviews all manuscripts submitted for publication but was not involved in the decision to publish.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Dr. Wang and Dr. Larson had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Cheng, Larson, Benjamin, Vasan, Wang. Acquisition of data: Cheng, Benjamin, Vasan, Wang. Analysis and interpretation of data: Cheng, Keyes, Larson, Levy, McCabe, Newton-Cheh, Benjamin, Vasan, Wang. Drafting of the manuscript: Cheng, Vasan, Wang. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Keyes, Larson, McCabe, Newton-Cheh, Levy, Benjamin. Statistical analysis: Keyes, Larson, McCabe. Obtained funding: Vasan, Wang. Administrative, technical, or material support: Levy, Vasan, Wang. Study supervision: Vasan, Wang.

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no relevant disclosures.

References

- 1.Packard JM, Graettinger JS, Graybiel A. Analysis of the electrocardiograms obtained from 1000 young healthy aviators; ten year follow-up. Circulation. 1954;10:384–400. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.10.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn H, Taylor HL, Keys A. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. XVI. The electrocardiogram in prediction of five-year coronary heart disease incidence among men aged forty through fifty-nine. Circulation. 1970;41:I154–I161. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.4s1.i-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose G, Baxter PJ, Reid DD, McCartney P. Prevalence and prognosis of electrocardiographic findings in middle-aged men. Br Heart J. 1978;40:636–643. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.6.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erikssen J, Otterstad JE. Natural course of a prolonged PR interval and the relation between PR and incidence of coronary heart disease. A 7-year follow-up study of 1832 apparently healthy men aged 40–59 years. Clin Cardiol. 1984;7:6–13. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartzman D. Atrioventricular block and atrioventricular dissociation. In: Zipes D, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. pp. 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mymin D, Mathewson FA, Tate RB, Manfreda J. The natural history of primary first-degree atrioventricular heart block. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1183–1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611063151902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE., Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41:279–281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.41.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:655–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay J, Jr., Hurst JW. The clinical features of atrial flutter and their therapeutic implications. Chest. 1974;66:114–121. doi: 10.1378/chest.66.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Agostino RB, Lee ML, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent Cox regression analysis: the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med. 1990;9:1501–1515. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780091214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kannel WB, Gordon T, Castelli WP, Margolis JR. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1970;72:813–822. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98:476–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:2455–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Adverse effect of ventricular pacing on heart failure and atrial fibrillation among patients with normal baseline QRS duration in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;107:2932–2937. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072769.17295.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS Institute Inc. SAS(R) ODBC Driver 9.1: User's Guide and Programmer's Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perlman LV, Ostrander LD, Jr., Keller JB, Chiang BN. An epidemiologic study of first degree atrioventricular block in Tecumseh, Michigan. Chest. 1971;59:40–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.59.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita S, Konishi G. Atrioventricular Wenckebach periodicity in athletes: influence of increased vagal tone on the occurrence of atypical periods. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:272–279. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(87)80026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crouse SF, Meade T, Hansen BE, Green JS, Martin SE. Electrocardiograms of collegiate football athletes. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:37–42. doi: 10.1002/clc.20452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bjornstad HH, Bjornstad TH, Urheim S, Hoff PI, Smith G, Maron BJ. Long-term assessment of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings in Norwegian elite endurance athletes. Cardiology. 2009;112:234–241. doi: 10.1159/000151435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleg JL, Das DN, Wright J, Lakatta EG. Age-associated changes in the components of atrioventricular conduction in apparently healthy volunteers. J Gerontol. 1990;45:M95–M100. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.3.m95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakatta EG, Gerstenblith G, Angell CS, Shock NW, Weisfeldt ML. Diminished inotropic response of aged myocardium to catecholamines. Circ Res. 1975;36:262–269. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin FC, Spurgeon HA, Greene HL, Lakatta EG, Weisfeldt ML. Age-associated decrease in heart rate response to isoproterenol in dogs. Mech Ageing Dev. 1979;10:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(79)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lev M. Anatomic Basis for Atrioventricular Block. Am J Med. 1964;37:742–748. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dilaveris PE, Gialafos EJ, Sideris SK, et al. Simple electrocardiographic markers for the prediction of paroxysmal idiopathic atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1998;135:733–738. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darbar D, Jahangir A, Hammill SC, Gersh BJ. P wave signal-averaged electrocardiography to identify risk for atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:1447–1453. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada T, Fukunami M, Shimonagata T, et al. Dispersion of signal-averaged P wave duration on precordial body surface in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:211–220. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal YK, Aronow WS, Levy JA, Spodick DH. Association of interatrial block with development of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:882. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leier CV, Meacham JA, Schaal SF. Prolonged atrial conduction. A major predisposing factor for the development of atrial flutter. Circulation. 1978;57:213–216. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.57.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson RJ, Jr., Foster JR, Gettes LS. Atrial excitability and conduction in patients with interatrial conduction defects. Am J Cardiol. 1982;50:1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnittger I, Appleton CP, Hatle LK, Popp RL. Diastolic mitral and tricuspid regurgitation by Doppler echocardiography in patients with atrioventricular block: new insight into the mechanism of atrioventricular valve closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa T, Kimura K, Miyazaki N, et al. Diastolic mitral regurgitation in patients with first-degree atrioventricular block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1992;15:1927–1931. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1992.tb02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, et al. Development of a Risk Score for Atrial Fibrillation in the Community. Lancet. 2008 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60443-8. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dilaveris PE, Farbom P, Batchvarov V, Ghuran A, Malik M. Circadian behavior of Pwave duration, P-wave area, and PR interval in healthy subjects. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2001;6:92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2001.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason JW, Ramseth DJ, Chanter DO, Moon TE, Goodman DB, Mendzelevski B. Electrocardiographic reference ranges derived from 79,743 ambulatory subjects. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freed LA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, et al. Mitral valve prolapse in the general population: the benign nature of echocardiographic features in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]