Abstract

Recent studies suggest that calcium influx via L-type calcium channels is necessary for psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization. In addition, chronic amphetamine upregulates subtype Cav1.2-containing L-type calcium channels. In the present studies, we assessed the effect of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) on cocaine-induced behavioral sentitization and determined whether the functional activity of L-type calcium channels is altered after repeated cocaine administration. Rats were administered daily intraperitoneal injections of either flunarizine (40 mg/kg), diltiazem (40 mg/kg) or cocaine (20 mg/kg) and the combination of the CCB’s and cocaine for 30 days. Motor activities were monitored on Day 1, and every 6th day during the 30-day treatment period. Daily cocaine administration produced increased locomotor activity. Maximal augmentation of behavioral response to repeated cocaine administration was observed on Day 18. Flunarizine pretreatment abolished the augmented behavioral response to repeated cocaine administration while diltiazem was less effective. Measurement of tissue monoamine levels on Day 18 revealed cocaine-induced increases in DA and 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens. By contrast to behavioral response, diltiazem was more effective in attenuating increases in monoamine levels than flunarizine. Cocaine administration for 18 days produced increases in calcium-uptake in synaptosomes prepared from the nucleus accumbens and frontal cortex. Increases in calcium-uptake were abolished by flunarizine- and diltiazem-pretreatment. Taken together, the augmented cocaine-induced behavioral response on Day 18 may be due to increased calcium uptake in the nucleus accumbens leading to increased dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT) release. Flunarizine and diltiazem attenuated the behavioral response by decreasing calcium uptake and decreasing neurochemical release.

Keywords: cocaine, sensitization, calcium channel blockers, motor activity, synaptosomes, rat

INTRODUCTION

Cocaine is a powerful psychostimulant known to be one of the most strongly reinforcing drugs of abuse. Cocaine binds to dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) transporters, blocking the reuptake and subsequent increase in extracellular monoamine levels in the neuronal terminal structures (Ritz et al., 1990; Andrews and Lucki, 2001). In humans, cocaine induces feelings of intense euphoria which often leads to dependence. In rodents, repeated cocaine administration produces the phenomenon called behavioral sensitization, manifested as progressive and enduring augmentation of locomotor activity in response to intermittent drug administration (Kalivas et al., 1998; Robinson and Berridge, 2003). Behavioral sensitization is believed to reflect drug-induced paranoia, craving and relapse (Kalivas et al., 1998; Robinson and Berridge, 2001). We and others have reported that L-type calcium channel blockers (CCBs) modulate a variety of cocaine-induced behaviors. For example, parenteral administration of CCBs impairs cocaine-stimulated locomotor activity (Mills et al., 1998; Pani et al., 1990a), cocaine self-administration (Kuzmin et al., 1992; Martellotta et al., 1994), cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Pani et al., 1991; Calcagnetti et al., 1995) and behavioral sensitization to repeated cocaine administration (Karler et al., 1991; Reimer and Martin-Iverson 1994). In addition, it has been shown that direct infusion of CCBs into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) attenuates the development of psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization (Licata and Pierce 2003) and repeated microinjection of the calcium channel agonist BayK 8644 into the VTA resulted in an augmentation of the behavioral response to cocaine (Licata et al., 2000). L-type calcium channels also play a role in the augmented DA release observed during the expression of sensitized behavior (Pierce and Kalivas, 1997). These data suggest that calcium influx via L-type calcium channels is necessary for psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization (Licata and Pierce 2003). Consistent with this is the fact that chronic amphetamine upregulates subtype Cav1.2-containing L-type calcium channels, and the ability of the CCB, diltiazem to increase amphetamine-mediated phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) in the DA neurons of the VTA (Rajadhyaksha et al., 2004). It is not known whether the upregulation of the Cav1.2-containing L-type calcium channels is accompanied by increase in the functional activity of the channels. In the present studies, we assessed the functional activity of L-type calcium channels by measuring synaptosomal Ca2+ transport after repeated cocaine administration and the effect of the CCB’s flunarizine and diltiazem on 45Ca2+-uptake into synaptosomes. We also determined the effects of the CCB’s on the augmented motor activity produced by subchronic cocaine administration. Moreover, monoamine analysis was done to determine if the augmented behavioral response to cocaine is accompanied by increases in monoamine levels in the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus and frontal cortex and whether the increased monoamine levels can be prevented by pretreatment with CCB’s.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 250–300 grams were used. All animals were maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle. The number of animals used per group in the locomotor activity studies is 7–12. For monoamine analysis and 45Ca2+-uptake studies, 4 animals per group were used. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Care and Use Committee at Meharry Medical College, provided by the National Institutes of Health.

Behavioral Analysis

Motor activity (expressed as Total Distance) was measured using commercially available activity monitoring chambers (AccuScan Instruments, Columbus, OH). The chambers (41 × 41 × 41 cm) which consisted of transparent Plexiglas cages with photocells and detectors interfaced to an IBM computer was used to determine distance traveled. Each animal was individually habituated to the activity cage for 30 minutes before a 60 minute test session. The calcium channel blockers (CCB) flunarizine (40 mg/kg) and diltiazem (40 mg/kg) or vehicle (1 ml/kg) were administered prior to the habituation period and cocaine (20 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) was injected before the test session. The treatment groups are: (1) DMSO + Saline; Flunarizine + Saline; DMSO + Cocaine; Flunarizine + Cocaine (2) Saline + Saline; Diltiazem + Saline; Saline + Cocaine; Diltiazem + Cocaine. All drugs were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.). Drug or vehicle was administered daily for a period of 30 days. Activity was monitored every 6th day during the 30 day period. The frequent monitoring of locomotor activity allowed us to monitor the development and progression of sensitization. At Day 18 and 30 time points, animals were sacrificed for neurochemical assays and 45Ca2+-uptake. The doses of cocaine and CCB’s were selected based on previous studies in our laboratory (Mills, 1998).

Monoamine Analysis

At the end of behavioral assessment, animals were decapitated and the brains were removed. The nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus and frontal cortex were dissected and weighed. Neurochemical analyses were performed as described previously (Ali et al., 1996; Mills et al., 1998). The respective tissues were individually sonicated with cell disruptor (Smith Kline) in 20 times volume of 0.2N perchloric acid. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 7 minutes at 13,000 × g. A 150-μL aliquot of the supernatant was placed in a centrifugal 0.45-μM nylon-66 filter (Rainin Instrument, Woburn, MA) and recentrifuged at 4°C for 3.5 minutes. Twenty-five microliters of the sample was injected on the column for analysis using a high-performance liquid chromatography electrochemical detector (HPLC-ED; Bioanalytical System, W. Lafayette, IN.).

Preparation of Synaptosomes

Animals were pretreated with either vehicle or CCB as described in behavioral analysis. Sixty minutes after either cocaine (20mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle administration, animals were decapitated and the brains were removed. The nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus and frontal cortex were dissected and weighed. Tissues from the nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus were combined and pooled with tissue from two animals. Tissues from the frontal cortex were similarly pooled from two animals. Synaptosomes were prepared according the method of Dodd and coworkers with minor modifications (Dodd et al., 1981). In brief, tissues were homogenized in 10 mL of ice cold buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.05) using a glass homogenizer with a teflon pestle. All subsequent steps were done at 0–4°C. The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant was taken and recentrifuged at 9000g. The pellet was suspended in 10 ml of 0.32 M sucrose and layered on 8 ml of 1.2 M sucrose. The suspension was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 45,000 rpm (Sorvall Ti 70 rotor, Dupont Co., Wilmington, DE.) and the interface layer was collected and diluted with 0.32 M sucrose to a final volume of 10 ml. The suspension was then layered on 8 ml of 0.8 M sucrose and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 45,000 rpm. The synaptosomal pellet was then resuspended in a total volume of 1 ml of 0.32 M sucrose and divided into two 0.5 ml aliquots for 45Ca-uptake assay.

Calcium Uptake

Aliquots (0.1 ml) of the synaptosomal suspension were added to glass tubes containing 0.35 ml of NaCl buffer (136 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 1.3 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris HCl, 11 mM glucose, pH 7.4). The tubes were pre-incubated for 20 minutes on ice and for 10 minutes at 37°C in a shaking water bath. Uptake was initiated by adding 0.025 ml of 45CaCl2 (0.5 Ci/assay), in 1 M NaCl for non-depolarizing conditions and in 1 M KCl for depolarizing conditions. Cold CaCl2 (0.025 ml of 1.28 mM) was added concurrently and incubated for 40 seconds. Uptake was terminated by rapid filtration through GF-B fiber filters and washed with 5 ml of cold buffer (145 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4). The amount of radioactivity on the filter disc was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al., (1951). Calcium uptake was expressed as cpm per mg protein.

Drugs

45Ca2+ (45CaCl2) was purchased from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Irvine, CA.). Cocaine hydrochloride, flunarizine hydrochloride, diltiazem hydrochloride and dimethylsulfoxide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO.).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the group means ± the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Temporal data of total distance were analyzed by a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures on drug treatment and time. A significant drug × time interaction was followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Monoamine levels and calcium uptake data were subjected to a one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Data were analyzed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A value of p< 0.05 indicates significance.

RESULTS

Behavioral analysis

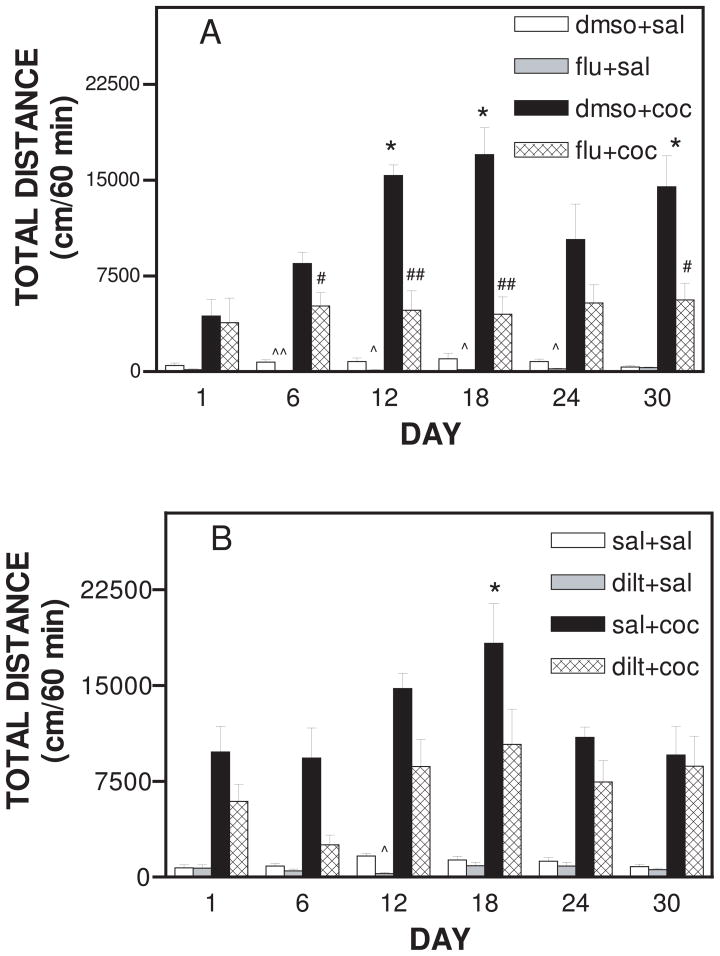

In a separate set of experiments we determined that acute or subchronic treatment with the vehicle for flunarizine, DMSO had no effect on basal motor behavior. “Subchronic” refers to treatment period between a week (acute) and 90 days to a year (chronic). As shown in figure 1A, main effect of treatment was observed for locomotor activity (F23,215 = 19.333; p<0.0001). Bonferroni post-hoc analysis revealed that daily pretreatment with flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly attenuated basal locomotor activity (Fig. 1A). Flunarizine decreased basal locomotor activity on day 6 (p <0.001), day 12 (p <0.01), day 18 (p <0.01), day 24 (p <0.01) as compared to vehicle plus saline control (Fig. 1A). Cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) produced increases in locomotor activity on all days tested (Fig. 1A). When compared to day 1, 18 days of cocaine administration produced maximal responses (p<0.001) to locomotor behavior (Fig. 1A). Administration of cocaine for 18 days increased the total distance traveled from 3392±1334 (day 1, cocaine treatment) to 16994±2109 (day 18, cocaine treatment) (Fig. 1A). Pretreatment with flunarizine significantly attenuated cocaine-induced locomotor activity on day 6 (p<0.05), day 12 (p<0.001); day 18 (p<0.001); and day 30 (p<0.05); as shown in Fig. 1A. Pretreatment with flunarizine on day 18 was most effective in attenuating cocaine-induced activity. Pretreatment with flunarizine on day 18 attenuated cocaine-induced total distance traveled from a peak of 16994±2109 to 4491±1369. Flunarizine appears to block cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization because flunarizine pretreatment decreased cocaine-induced locomotor activity to pre-sentitization cocaine response (Day 1). The effect of flunarizine on basal activity cannot account for its effects on cocaine-induced sensitization because flunarizine had no effect on cocaine-induced locomotor activity on Day 1 when sensitization to cocaine had not developed.

Figure 1.

Effect of daily flunarizine and diltiazem pretreatment on cocaine–induced motor activity in rats during a 30 day treatment period. Total Distance is expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for n=7–12 rats per group. A. Animals were pretreated daily with flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.). Thirty minutes after pretreatment animals were given a daily cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) challenge and motor activity was monitored for 60 minutes every 6th day. *represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to dmso+coc on day 1. #represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to respective daily dmso+coc values, ##represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to respective daily dmso+coc values, ^represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to respective daily dmso+sal values, and ^^represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to respective daily dmso+sal values. B. Animals were pretreated daily with diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.). Thirty minutes after pretreatment animals were given a daily cocaine (20 mg/kg,i.p.) challenge and motor activity was monitored for 60 minutes every 6th day. *represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to sal+coc on day 1, ^represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to Day 12 sal+sal value.

In fig 1B, the main effect of treatment was evident for locomotor activity (F23, 213 = 13.337; p <0.0001). Diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreatment decreased basal locomotor activity on day 12, (p <0.001) as compared to respective day 12 saline controls (Fig. 1B). Cocaine administration produced a peak effect (p<0.05) on day 18 of cocaine treatment (Fig. 1B).

Monoamine analysis

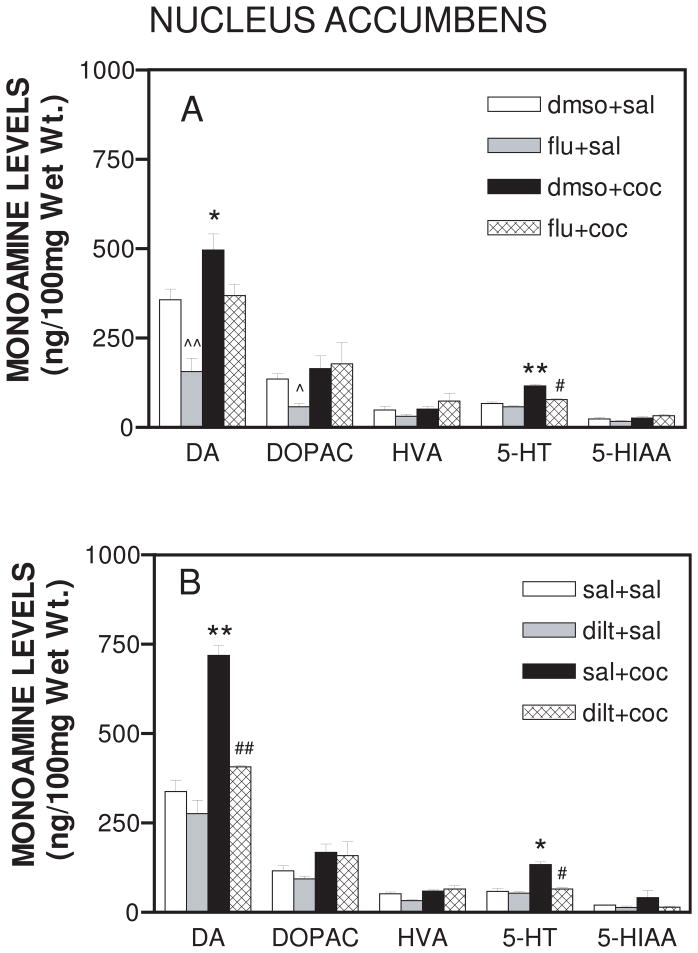

Figure 2A and 2B show the levels of DA, 5-HT, and the metabolites DOPAC, HVA and 5-HIAA in the nucleus accumbens on day 18. Cocaine treatment produced significant changes in the levels of monoamines (F19,60 = 97.69; p<0.0001) when compared to saline treated animals. The levels of DA in the nucleus accumbens increased from 357.4±29.7 to 496.3±45.3 after cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) administration (p<0.05). Similarly, the levels of 5-HT increased from 66.8±4.19 to 116±4.4 (p<0.001) after cocaine administration. Flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreatment decreased basal DA (p<0.001) and DOPAC levels (p <0.05). Figure 2A also shows that flunarizine inhibited the increase in 5-HT (p<0.001) but not DA levels induced by cocaine administration. On the other hand, diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreatment attenuated (F19,60 = 97.69; p<0.0001) cocaine-induced increases in both DA (p<0.001) and 5-HT (p<0.01) as depicted in Fig 2B.

Figure 2.

A. Effect of daily flunarizine pretreatment on tissue monoamine levels in the nucleus accumbens after 18-day cocaine treatment. On each day, animals were either pretreated with flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or dmso vehicle (1 ml/kg,i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). One hour after cocaine or saline injection on day 18, the nucleus accumbens was dissected and analyzed for dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT) and metabolites DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for n=4 rats per group. *represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to dmso+sal values, **represents significance at p<0.001, as compared to dmso+sal values, #represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to dmso+coc values, ^represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to dmso+sal values, and ^^represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to dmso+sal values.

B. Effect of daily diltiazem pretreatment on extracellular monoamine levels in the nucleus accumbens produced by 18-day cocaine treatment. On each day, animals were either pretreated with diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). One hour after cocaine or saline injection on day 18, the nucleus accumbens was dissected and analyzed for dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT) and metabolites DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA. *represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to sal+sal values, **represents significance at p<0.001, as compared to sal+sal values, #represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+coc values, and ##represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to sal+coc values.

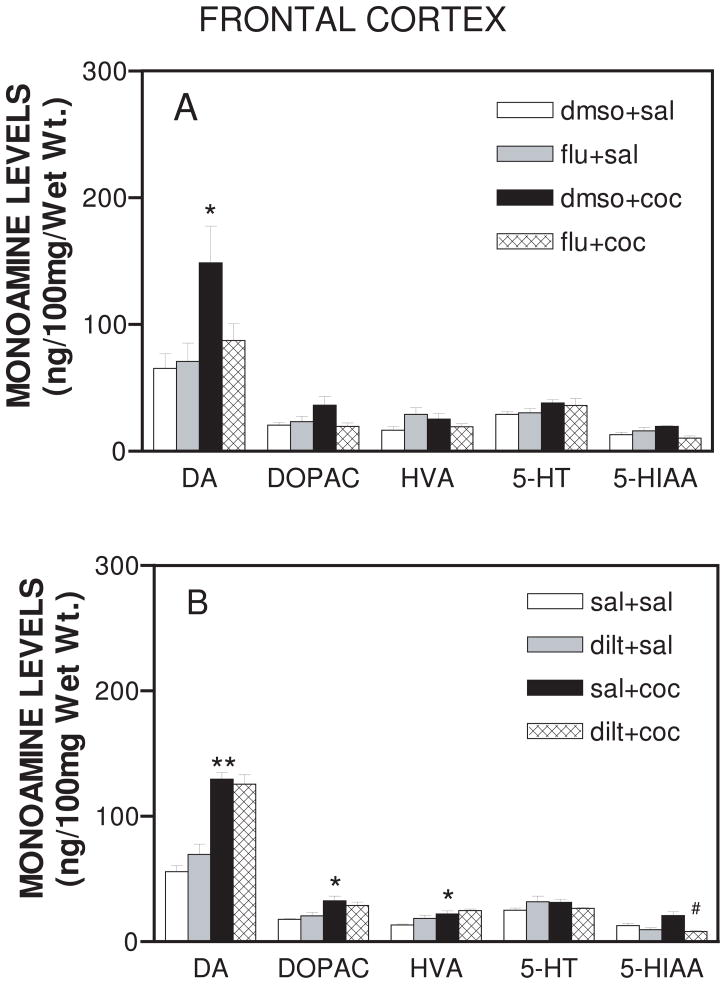

Basal monoamine levels in the frontal cortex were not affected by either flunarizine or diltiazem pretreatment. Cocaine increased DA levels in the frontal cortex in both the flunarizine (F19, 60 = 13.864; p<0.05) (Fig. 3A) and the diltiazem (F19,60 = 90.723; p<0.0001) (Fig. 3B) treated groups. Neither flunarizine nor diltiazem pretreatment significantly affected cocaine-induced increase in DA levels in the frontal cortex, although flunarizine treatment exhibited a decreasing trend toward cocaine-induced DA levels (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, diltiazem inhibited (p<0.05) levels of 5-HIAA after cocaine treatment. Similarly, pretreatment with either flunarizine or diltiazem produced no significant changes in either basal or cocaine-evoked monoamine levels in the caudate nucleus (data not shown).

Figure 3.

A. Effect of daily flunarizine pretreatment on tissue monoamine levels in the frontal cortex after 18-day cocaine treatment. On each day, animals were either pretreated with flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or dmso vehicle (1 ml/kg,i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). One hour after cocaine or saline injection on day 18, the frontal cortex was dissected and analyzed for dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT) and metabolites DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. for n=4 rats per group. *represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to dmso+sal values.

B. Effect of daily diltiazem pretreatment on extracellular monoamine levels in the frontal cortex produced by 18-day cocaine treatment. On each day, animals were either pretreated with diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). One hour after cocaine or saline injection on day 18, the frontal cortex was dissected and analyzed for dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT) and metabolites DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA. *represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to sal+sal values, **represents significance at p<0.001, as compared to sal+sal values, and #represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to sal+coc values.

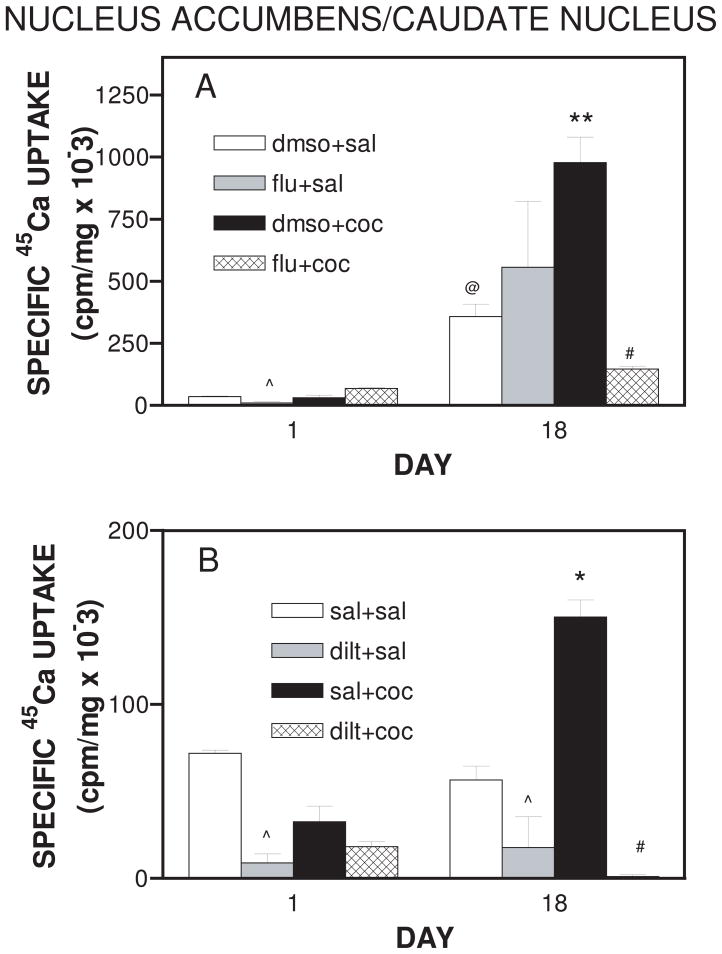

Calcium uptake studies

There was main effect of treatment (F7,24 = 11.175; p<0.0001). Acute administration of flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) on Day 1 decreased (p<0.05) Ca2+-uptake into synaptosomes prepared from nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus (Fig. 4A). Acute administration of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) on Day 1 did not affect 45Ca2+-uptake into synaptosomes prepared from nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus (Fig. 4A). On Day 18, there was an increase (p<0.001) in basal 45Ca2+-uptake in the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus (Fig. 4A). The increase in basal 45Ca2+-uptake could be attributed to the effect of DMSO since this effect was not observed when saline was used as the vehicle (Fig 4B). However, this assertion is not in agreement with the observation that in human erythrocytes, DMSO inhibits calcium transport (Romero, 1992). It is possible that the effects of DMSO are dependent on the cell type. Cocaine administration potentiated 45Ca2+-uptake on Day 18 (p<0.001) (Fig. 4A). Flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) was effective in attenuating (p<0.001) the increase in 45Ca2+-uptake produced by cocaine on Day 18 (Fig. 4A). Flunarizine pretreatment reduced 45Ca2+-uptake induced by cocaine in the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus by 83 % (Fig. 4A)

Figure 4.

A. Synaptosomal 45Ca2+ uptake in the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus of rats receiving daily treatment with flunarizine or cocaine in the presence of flunarizine for 18 days. On each day, animals were pretreated with either flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or dmso (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) and tissue was collected as described in methods. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M for N=4 rats per group. @represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to respective Day 1 value, **represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to dmso+sal on Day 18, #represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to dmso+coc on Day 18, and ^represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to dmso+sal on Day 1. B. Synaptosomal 45Ca2+ uptake in the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus of rats receiving daily treatment with diltiazem or cocaine in the presence of diltiazem for 18 days. On each day, animals were pretreated with either diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) and tissue was collected as described in methods. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M for N=4 rats per group. *represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+sal on Day 18, #represents significance at p<0.001 as compared to sal+coc on Day 18, and ^represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+sal. Note the difference in scales between the two figures.

There was main effect of treatment in the diltiazem treatment group (F7,24 = 43.843; p<0.0001). As shown in Fig. 4B, diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) pretreatment reduced (p <0.01) 45Ca2+-uptake in the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus as compared to the saline controls on Day 1 and Day 18. Cocaine administration potentiated 45Ca2+-uptake on Day 18 (p<0.01). Diltiazem pretreatment also effectively blocked (98% decrease) 45Ca2+-uptake (p<0.001) induced by cocaine in synaptosomes prepared from nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus.

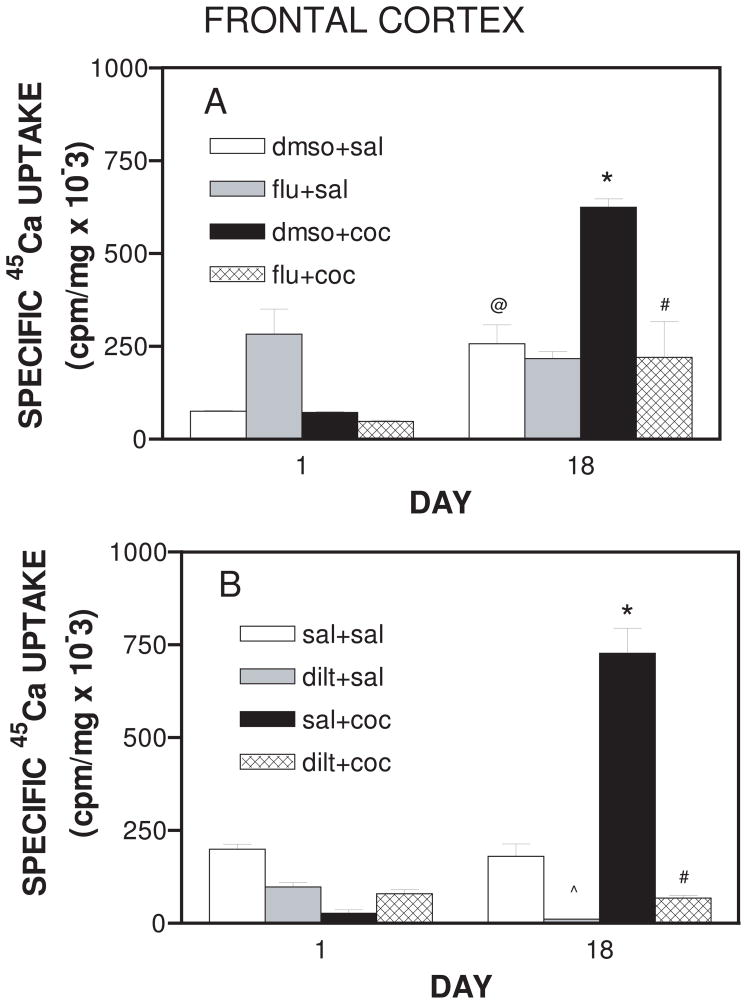

Main effect of treatment was evident in the frontal cortex as well (F7,24 = 24.437 p<0.001 Fig. 5A and F7,24 = 67.116; p<0.001 Fig. 5B respectively). Cocaine administration significantly increased (p<0.01) 45Ca2+-uptake in the frontal cortex on Day 18. Both flunarizine (p<0.05) and diltiazem (p<0.01) reduced cocaine-induced Ca2+-uptake on Day 18 (Fig. 5A and 5B).

Figure 5.

A. Synaptosomal 45Ca2+ uptake in the frontal cortex of rats receiving daily treatment with flunarizine or cocaine in the presence of flunarizine for 18 days. On each day, animals were pretreated with either flunarizine (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or dmso (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) and tissue was collected as described in methods. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M for N=4 rats per group. @represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to respective Day 1 value, *represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to dmso+sal on Day 18 and #represents significance at p<0.05 as compared to dmso+coc on Day 18.

B. Synaptosomal 45Ca2+ uptake in the frontal cortex of rats receiving daily treatment with diltiazem or cocaine in the presence of diltiazem for 18 days. On each day, animals were pretreated with either diltiazem (40 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). After 30 minutes animals were administered either cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.) and tissue was collected as described in methods. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M for N=4 rats per group. *represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+sal on Day 18, #represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+coc on Day 18, and ^represents significance at p<0.01 as compared to sal+sal.

DISCUSSION

Our data provide three lines of evidence to suggest that voltage-dependent calcium channels play a role in the enhanced locomotor response to repeated cocaine administration. Firstly, using augmented behavioral response to subchronic cocaine on day 18 of daily administration as a behavioral end-point, the CCB flunarizine attenuated cocaine-induced behavioral effects. Secondly, increases in nucleus accumbens monoamine levels induced by cocaine was blocked by the CCB diltiazem. Thirdly, 45Ca2+-uptake was enhanced in synaptosomes prepared from the striatum and frontal cortex of rats treated for 18 days with cocaine. This enhanced Ca2+-uptake was abolished by pretreatment with the CCB’s. The major contribution of this study is that we demonstrated that repeated cocaine adminstration produces behavioral sensitization and increases 45Ca2+-uptake, both of which are sensitive to the CCB flunarizine. The observed cocaine-induced increase in functional activity of the L-type Ca2+ channels is in agreement with studies showing upregulation of Cav1.2-containing L-type calcium channels after chronic amphetamine administration (Rajadhyaksha et al., 2004). The doses of cocaine and CCBs were selected based on previous studies in our laboratory (Mills, 1998) and are in the same order of magnitude as others used by other investigators (Karler et al., 1991; Pani et al., 1990a). However the authors acknowledge the limitations of using single doses of drugs in this study. Differences between the cocaine-induced increases in DA levels in the DILT group and the FLU group (Fig 2A and 2B) as well as the huge differences in cocaine-induced Ca2+-uptake in the nucleus accumbens in the FLU experiment compared to the DILT experiment (Fig 4A and 4B) are a concern and may have made our findings much less compelling. However, we do not think they had a major impact on our overall finding because the changes in the respective groups were qualitatively similar despite the obvious differences in magnitude of the effects.

Behavioral sensitization is a phenomenon whereby responses increase in magnitude to repeated administration of a drug at the same dose (Kalivas et al., 1998; Robinson and Berridge, 2003) and has been reported to be commonly induced by administration of single daily doses of cocaine followed by a withdrawal period and then a challenge phase in which a single “challenge” dose of cocaine is administered. There are many studies which report that repeated administration of cocaine produces behavioral sensitization (Beyer and Steketee, 1999; Bhargava et al., 1997; Bohn et al., 2003; Henry et al., 1995; Izenwasser and French, 2002; Martin-Iverson et al., 1995; Polston et al., 2006; Post et al., 1976). On the other hand continuous infusion of cocaine produces tolerance (Izenwasser and French, 2002; King et al., 1999; Kunko et al., 1998). Although continuous infusion of cocaine has been shown to produce tolerance, behavioral sensitization can develop following intermittent cocaine administration even in absence of a withdrawal period (Ansah et al., 1996; Bhargava et al., 1997; Polston et al., 2006; Post et al., 1976). In our studies, daily administration of a moderate dose of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) produced behavioral sensitization to locomotor activity on each day that activity was monitored up to day 18, although the increases observed were not sustained throughout the 30 day testing paradigm. Similarly, Polston et al (2006) induced behavioral sensitization in rats by administration of 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p. cocaine daily for 12 consecutive days and testing for sensitization on Day 13. Bhargava and Kumar (1997) also reported inducing behavioral sensitization in mice after subchronic administration of cocaine. The pattern of motor activity observed is consistent with that generated previously in our laboratory after daily intermittent cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) administration (Ansah et al., 1996). Sensitization dropped off after Day 18, possibly due to tolerance. This observation is at odds with the general notion that tolerance typically develops after continuous drug infusion (Izenwasser and French, 2002; King et al., 1999; Kunko et al., 1998). Treatment with cocaine over the extended period of time (30 days) in our studies may have contributed to the development of tolerance after Day 18 of treatment.

Flunarizine was more effective in attenuating the augmented locomotor response elicited by cocaine on day 18 (Fig. 1A) than diltiazem (Fig. 1B). Flunarizine inhibited cocaine-induced locomotor activity by 73% on day 18 whereas diltiazem inhibited only 43% of cocaine-induced locomotor activity. On the other hand, the same dose of diltiazem significantly decreased cocaine-induced increases in DA levels (45% decrease) whereas flunarizine was not effective (20% decrease). Thus the CCB’s had differential effects on cocaine-stimulated behavior and cocaine-induced DA metabolism. We and others have previously reported that acute administration of L-type CCB’s belonging to different groups (i.e. 1–4 dihydropyridine, phenylalkylamine, benzothiazepine) may have differential affects on cocaine-induced behaviors (Ansah et al., 1993; Pani et al., 1990a; 1990b; 1990c). In addition, previous studies in our laboratory have identified differences in the magnitude of inhibition of acute cocaine-induced locomotor behavior by pretreatment with various CCB’s (i.e. isradipine, nicardipine, and verapamil) (Mills et al., 1994). Pani and coworkers (Pani et al.1990a) reported that nimodipine and isradipine inhibited cocaine-induced motor stimulation while flunarizine potentiated motor stimulation induced by cocaine. In contrast to the findings by Pani’s group our results found no effects of acute (ie. day 1) flunarizine pretreatment on cocaine-induced motor activity (Fig. 2A and 2B). Flunarizine significantly attenuated the locomotor effects of cocaine on day 18 of a 30 day test period. The differences observed between our findings and those of Pani and coworkers could be due to the route of administration and/or dose of flunarizine tested. For example, Pani’s group used a dose of 20 mg/kg of flunarizine administered subcutaneously. In our study, a dose of 40 mg/kg of flunarizine administered intraperitoneally was used. Furthermore Pani’s group used a dose of 10 mg/kg cocaine (s.c) while we used 20 mg/kg (i.p.).

Subchronic, 18 day cocaine administration did not increase monoamine levels in the caudate nucleus, but produced significant increases in DA and 5-HT levels in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 2A and 2B). Similarly, DA levels as well as the metabolites DOPAC, HVA, and 5-HIAA in the frontal cortex were augmented by cocaine administration (Fig. 3A and 3B). Previously we have reported that acute cocaine produces increases in DA and 5-HT in the rat nucleus accumbens and the caudate nucleus although the increases observed were not statistically significant (Mills et al., 1998). It appears that under acute conditions the cocaine-induced increases in monoamine levels are transient and that our previous studies using one time point (ie. Day 1) measurement may have missed the peak effects. We do show however in the present studies that following 18 day treatment with cocaine, the augmented behavioral response is accompanied by increases in DA and 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens – a site critical for the behavioral effects of cocaine (Broderick et al., 1993; Reith et al., 1997). It is well documented that both behavioral modification and addictive properties of cocaine result mainly from its binding to the DA transporter (DAT) and inhibition of DA reuptake, thus elevating extracellular DA concentration and prolonging signaling at synapses (Amara and Sonders, 1998). In vivo imaging studies in humans and in vitro studies in post-mortem human brain have demonstrated that chronic cocaine abuse results in increase in DAT-binding site and DAT function (Malison et al., 1998; Mash et al., 2002). The increased neuroadaptive changes in DAT function following chronic cocaine could alter DA metabolism and DA tissue content.

L-type calcium channels are localized in CNS areas with a high density of synaptic connections (Gould et al., 1984) and are involved in neurotransmitter release (Snyder et al., 1983). Perfusion of the L-type CCB verapamil or nicardipine into the rat striatum has been shown to produce a dose-dependent decrease of DA in the microdialysis perfusate. Previously we have reported that acute administration of isradipine, an L-type CCB decreased cocaine-induced DA and 5-HT in both the nucleus accumbens and the caudate nucleus in rats (Mills et al., 1998). Daily pretreatment with flunarizine for 18 days did not significantly decrease tissue DA levels while significantly attenuating tissue 5-HT levels in the nucleus accumbens after cocaine administration. Diltiazem on the other hand, attenuated both DA and 5-HT levels in the nucleus accumbens of rats in our study. Neither flunarizine nor diltiazem was effective in attenuating subchronic cocaine-induced increases in DA or 5-HT levels in the caudate nucleus or the frontal cortex. The fact that at Day 18, the CCB’s decreased cocaine augmented behavioral response and also blocked increases in tissue monoamine levels suggest that the CCB’s act centrally, especially in the nucleus accumbens to modulate behavioral response to cocaine.

Calcium uptake has been shown to be fundamental in the process of release of monoamines. For example, it has been demonstrated in rat neurons that an increase in intracellular calcium results in a subsequent increase in neurotransmitter release (Hurd et al., 1989). Furthermore studies in rat brain synaptosomes have demonstrated that CCB’s inhibit calcium uptake (Turner and Goldin, 1985;White and Bradford, 1986; Dunn, 1988) and neurotransmitter release (Blaustein, 1975; Raiteri and Levi, 1978). Cocaine administration for 18 days produced increases in 45Ca2+-uptake in synaptosomes prepared from rat nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus and frontal cortex. Pretreatment with flunarizine and diltiazem prevented the increases in 45Ca2+-uptake in synaptosomes prepared from both the nucleus accumbens/caudate nucleus and frontal cortex. Taken together, the augmented cocaine-induced behavioral response on Day 18 may be due to increased Ca2+-uptake in the nucleus accumbens leading to increased neurotransmitter release. Flunarizine and diltiazem may attenuate the behavioral response by decreasing calcium uptake and decreasing neurochemical release.

Evidence has accumulated that some classic L-type CCB’s may also inhibit T-type calcium channels in neurons (Stengel et al., 1998). Flunarizine and diltiazem have been reported to block both L-type and T-type calcium channels in cultured smooth muscle cells although flunarizine was reported to be a more effective T-type blocker than diltiazem (Kuga et al., 1990). The prevailing view is that L-type calcium channels play an important role in the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Systemic injections of CCBs block the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Reimer and Martin-Iverson, 1994). Moreover, repeated intra-VTA administration of the L-type calcium channel agonist BayK 8644 cross-sensitizes to a subsequent challenge injection of cocaine (Licata et al., 2000). It has been suggested that calcium influx into VTA neurons via L-type calcium channels is enhanced during the development of behavioral sensitization leading to persistent activation of calcium/calmodulin-stimulated kinases which are known to mediate behavioral plasticity (Licata and Pierce, 2003). The increased Ca2+-uptake following repeated cocaine administration could be due to increased protein level of the L-type calcium channels. For example, it has been shown that chronic amphetamine treatment increases the mRNA and protein expression of the L-type Ca2+ channel subunit Cav1.2 (Rajadhyaksha et al., 2004). Our functional data showing that the enhanced synaptosomal calcium transport following repeated cocaine administration is blocked by CCBs may provide additional evidence for the role of CCBs in the behavioral effects of cocaine.

CONCLUSION

In the present studies, we have shown that cocaine-induced motor behavior and synaptosomal calcium uptake are increased following repeated cocaine administration. These effects are attenuated by treatment with CCBs and provide further evidence that L-type calcium channels play an important role in the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep gratitude to the National Institutes of Health for financial support of this manuscript under grants DA06686, P32HL07809, NS041071, and S11 ES014156

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali SF, Newport GD, Slikker W, Jr, Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Neuroendocrine and neurochemical effects of acute ibogaine administration: a time course evaluation. Brain Research. 1996;737 (1–2):215–220. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00734-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amara SG, Sonders MS. Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51 (1–2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews CM, Lucki I. Effects of cocaine on extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155 (3):221–229. doi: 10.1007/s002130100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansah TA, Wade LH, Shockley DC. Effects of calcium channel entry blockers on cocaine and amphetamine-induced motor activities and toxicities. Life Sciences. 1993;53 (23):1947–1956. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90016-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansah TA, Wade LH, Shockley DC. Changes in locomotor activity, core temperature, and heart rate in response to repeated cocaine administration. Physiology and Behavior. 1996;60 (5):1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer CE, Steketee JD. Dopamine depletion in the medial prefrontal cortex induces sensitized-like behavioral and neurochemical responses to cocaine. Brain Research. 1999;833 (2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava HN, Kumar S. Sensitization to the locomotor stimulant activity of cocaine is associated with increases in nitric oxide synthase activity in brain regions and spinal cord of mice. Pharmacology. 1997;55 (6):292–298. doi: 10.1159/000139541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Langwinski R. Effects of calcium channel antagonists on the reinforcing properties of morphine, ethanol and cocaine as measured by place conditioning. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1996;47 (3):497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M. Effects of potassium, veratridine, and scorpion venom on calcium accumulation and transmitter release by nerve terminals in vitro. Journal of Physiology (Lond) 1975;247(3):617–655. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Sotnikova TD, Medvedev IO, Lefkowitz RJ, Dykstra LA, Caron MG. Enhanced rewarding properties of morphine, but not cocaine, in βarrestin-2 knock-out mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23 (32):10265–10273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PA, Kornak EP, Jr, Eng F, Wechsler R. Real time detection of acute (IP) cocaine-enhanced dopamine and serotonin release in ventrolateral nucleus accumbens of the behaving Norway rat. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;46 (3):715–722. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90567-D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagnetti DJ, Keck BJ, Quatrella LA, Schechter MD. Blockade of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: relevance to cocaine abuse therapeutics. Life Sciences. 1995;56 (7):475–483. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00414-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagnetti DJ, Schechter MD. Psychostimulant-induced activity is attenuated by two putative dopamine release inhibitors. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1992;43 (4):1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90476-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd PR, Hardy JA, Oakley AE, Edwardson JA, Perry EK, Delaunoy JP. A rapid method for preparing synaptosomes: Comparison with alternative procedures. Brain Research. 1981;226 (1–2):107–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn S. Multiple calcium channels in synaptosomes: voltage dependence of 1,4–dihydropyridine binding and effects on function. Biochemistry. 1988;27 (14):5275–5281. doi: 10.1021/bi00414a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales PM, Boswell KJ, Hubbell CL, Reid LD. Isradipine blocks cocaine’s ability to facilitate pressing for intracranial stimulation. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1997;58 (4):1117–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RJ, Murphy KM, Snyder SH. Autoradiographic localization of calcium channel antagonist receptors in the rat brain with 3[H] nitrendipine. Brain Research. 1984;330 (2):217–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Jones GH, Hubert GW, Neill DB, Justice JB., Jr Assessment of the relative contribution of peripheral and central components in cocaine place conditioning. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;47 (4):973–979. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DJ, White FJ. The persistence of behavioral sensitization to cocaine parallels enhanced inhibition of nucleus accumbens neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15 (4):6287–6299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06287.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Ungerstedt U. Ca2+ dependence of the amphetamine, nomifensine, and Lu 19-005 effect on in vivo dopamine transmission. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;166 (2):261–269. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y. Modulation of cocaine- and methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization by inhibition of brain nitric oxide synthase. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1997;282 (2):521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenwasser S, French D. Tolerance and sensitization to the locomotor-activating effects of cocaine are mediated via independent mechanisms. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;73 (4):877–882. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Pierce RC, Cornish J, Sorg BA. A role for sensitization in craving and relapse in cocaine addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacol. 1998;12 (1):49–53. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karler R, Turkanis SA, Partlow LM, Calder LD. Calcium channel blockers in behavioral sensitization. Life Sciences. 1991;49 (2):165–170. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90029-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Otsu Y, Furune Y, Yamamoto T. Different effects of L-, N- and T-type calcium channel blockers on striatal dopamine release measured by microdialysis in freely moving rats. Neurochemistry International. 1992;21 (1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GR, Xiong Z, Douglas S, Lee TH, Ellinwood EH. The effects of continuous cocaine dose on the induction of behavioral tolerance and dopamine autoreceptor function. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;376 (3):207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuga T, Sadoshima J, Tomoike H, Kanaide H, Akaike N, Nakamura M. Actions of Ca2+ antagonists on two types of Ca2+ channels in rat aorta smooth muscle cells in primary culture. Circulatory Research. 1990;67 (2):469–480. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunko PM, French D, Izenwasser S. Alterations in locomotor activity during chronic cocaine administration: effect on dopamine receptors and interaction with opioids. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;285 (1):277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin A, Zvartau E, Gessa GL, Martellotta MC, Fratta W. Calcium antagonists isradipine and nimodipine suppress cocaine and morphine intravenous self-administration in drug-naive mice. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1992;41 (3):497–500. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90363-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Freeman AY, Pierce-Bancroft AF. Repeated stimulation of L-type calcium channels in the rat ventral tegmental area mimics the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152 (1):110–118. doi: 10.1007/s002130000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Pierce RC. The roles of calcium/calmodulin-dependent and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinases in the development of psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;85 (1):14–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193 (1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malison RT, Best SE, Wallace EA, McCance E, Laruelle M, Zogbhi SS, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JS, Hoffer PB, Price LH, Kosten TR, Innis RB. Elevated striatal dopamine transporters during acute cocaine abstinence as measured by [123I]β-CIT SPECT. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155 (6):832–834. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martellotta MC, Kuzmin A, Muglia P, Gessa GL, Fratta W. Effects of the calcium antagonist isradipine on cocaine intravenous self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;113(3–4):378–380. doi: 10.1007/BF02245212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Iverson MT, Burger LY. Behavioral sensitization and tolerance to cocaine and the occupation of dopamine receptors by dopamine. Molecular Neurobiology. 1995;11 (1–3):31–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02740682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Pablo J, Ouyang Q, Hearn WL, Izenwasser S. Dopamine transport function is elevated in cocaine users. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81 (2):292–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K, Ansah TA, Ali SF, Shockley DC. Calcium channel antagonist isradipine attenuates cocaine-induced motor activity in rats: correlation with brain monoamine levels. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;844:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K. Ph.D. Dissertation. Meharry Medical College; Nashville, TN: 1998. The effect of various calcium channel blockers on cocaine-induced behavior in rats. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell LE, Sussman AN, Meyer KL, Neisewander JL. Behavioral effects of psychomotor stimulant infusions into amygdaloid nuclei. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20 (6):591–602. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabello NG, Hubbell CL, Cavallaro CA, Barringer TM, Mendez JJ, Reid LD. Responding for rewarding brain stimulation: cocaine and isradipine plus naltrexone. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1998;61 (2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Carboni S, Kuzmin A, Gessa GL, Rossetti ZL. Nimodipine inhibits cocaine-induced dopamine release and motor stimulation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990a;176 (2):245–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90537-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Carboni S, Kuzmin A, Gessa GL, Rossetti ZL. Flunarizine potentiates cocaine-induced dopamine release and motor stimulation in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990b;190 (1–2):223–227. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94129-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Carboni S, Kuzmin A, Gessa GL, Rossetti ZL. Calcium receptor antagonists modify cocaine effects in the central nervous system differently. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990c;190 (1–2):217–221. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94128-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani L, Kuzmin A, Martellotta MC, Gessa GL, Fratta W. The calcium antagonist PN 200–110 inhibits the reinforcing properties of cocaine. Brain Research Bulletin. 1991;26 (3):445–447. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90022-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2. Academic Press; San Diego: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine modifies the mechanism by which amphetamine releases dopamine. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17 (9):3254–3261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03254.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polston JE, Cunningham CS, Rodvelt KR, Miller DK. Lobeline augments and inhibits cocaine-induced hyperactivity in rats. Life Sciences. 2006;79 (10):981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Rose H. Increasing effects of repetitive cocaine administration in the rat. Nature. 1976;260 (5553):731–732. doi: 10.1038/260731a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri M, Levi G. Release mechanisms for catecholamines and serotonin in synaptosomes. Reviews in Neuroscience. 1978;3:78–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rajadhyaksha A, Husson I, Satpute SS, Kuppenbender KD, Ren JQ, Guerriero RM, Standaert DG, Kosofsky BE. L-type Ca2+ channels mediate adaptation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation in the ventral tegmental area after chronic amphetamine treatment. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24 (34):7464–7476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid LD, Pabello NG, Cramer CM, Hubbell CL. Isradipine in combination with naltrexone as a medicine for treating cocaine abuse. Life Sciences. 1997;60(8):PL119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer AR, Martin-Iverson MT. Nimodipine and haloperidol attenuate behavioral sensitization to cocaine but only nimodipine blocks the establishment of conditioned locomotion induced by cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;113 (3–4):404–410. doi: 10.1007/BF02245216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Cone EJ, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine inhibition of ligand binding at dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transportes: structure-activity study. Life Sciences. 1990;46 (9):635–645. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90132-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96 (1):103–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annual Reviews in Psychology. 2003 June 10;54 :25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero PJ. Inhibition of the human erythrocyte calcium pump by dimethyl sulfoxide. Cell Calcium. 1992;13 (10):659–667. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD. Cocaine discrimination is attenuated by isradipine and CGS 10746B. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;44 (3):661–664. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90183-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Tella SR, Prada J, Goldberg SR. Calcium channel blockers antagonize some of cocaine’s cardiovascular effects, but fail to alter cocaine’s behavioral effects. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1995;272 (2):791–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel W, Jainz M, Andreas K. Different potencies of dihydropyridine derivatives in blocking T-type but not L-type Ca2+ channels in neuroblastoma-glioma hybrid cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;342 (2–3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres G, Horowitz JM. Activating properties of cocaine and cocaethylene in a behavioral preparation of Drosophila melanogaster. Synapse. 1998;29 (2):148–161. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199806)29:2<148::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TJ, Goldin SM. Calcium channels in rat brain synaptosomes: identification and pharmacological characterization. High affinity blockade by organic Ca2+ channel blockers. Journal of Neuroscience. 1985;5 (3):841–849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00841.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White EJ, Bradford HF. Enhancement of depolarization-induced synaptosomal calcium uptake and neurotransmitter release by Bay K8644. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1986;35 (13):2193–2197. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]