Abstract

Background

Monomeric Group IVB (Ti, Zr and Hf) metallocenes represent a new class of antitumor compounds. There is literature on the general biological activities of some organotin compounds. Unfortunately, there is little information with respect to the molecular level activity of these organotin compounds. We recently started focusing on the anti-cancer activity of organotin polymers that we had made for other purposes and as part of our platinum anti-cancer effort.

Methods

For this study, we synthesized a new series of metallocene-containing compounds coupling the metallocene unit with dienestrol, a synthetic, nonsteroidal estrogen. This is part of our effort to couple known moieties that offer antitumor activity with biologically active units hoping to increase the biological activity of the combination. The materials were confirmed to be polymeric using light scattering photometry and the structural repeat unit was verified employing matrix assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy results.

Results

The polymers demonstrated the ability to suppress the growth of a series of tumor cell lines originating from breast, colon, prostrate, and lung cancers at concentrations generally lower than those required for inhibition of cell growth by the commonly used antitumor drug cisplatin.

Conclusion

These drugs show great promise in vitro against a number of cancer cell lines and due to their polymeric nature will most likely be less toxic than currently used metal-containing drugs such as cisplatin. These drugs also offer several addition positive aspects. First, the reactants are commercially available so that additional synthetic steps are not needed. Second, synthesis of the polymer is rapid, occurring within about 15 seconds. Third, the interfacial synthetic system is already industrially employed in the synthesis of aromatic nylons and polycarbonates. Thus, the ability to synthesize large amounts of the drugs is straight forward.

Background

We have synthesized a number of condensation organotin-containing polymers [1-12] and polymeric derivatives of cisplatin [13-17] emphasizing biological activities. Many of these have shown outstanding anticancer and antiviral agents properties as well as the expected antibacterial properties. In some of these efforts we emphasized the use of Lewis bases that themselves offered some biological activity including the known antiviral agent acyclovir and a number of proven antibacterial agents such as norfloxacin, ampicillin, tricarcillin, and ciprofloxacin. Our overall rationale for employing known drugs coupled with metal-containing moieties with characterized biological effects is to create a unique compound that can interact with the target (cancer, bacteria, virus) at several venues. By targeting multiple sites the possibility that the target will become resistant to the treatment is greatly reduced increasing the effectiveness of the treatment.

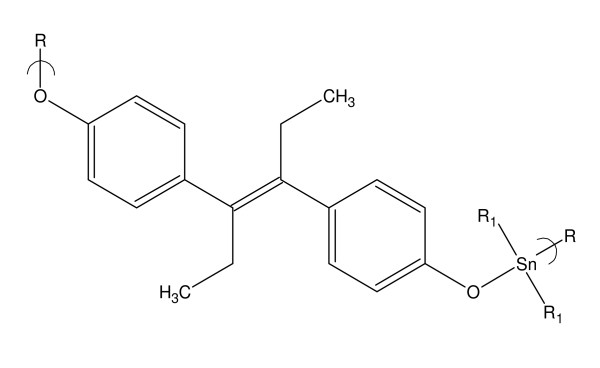

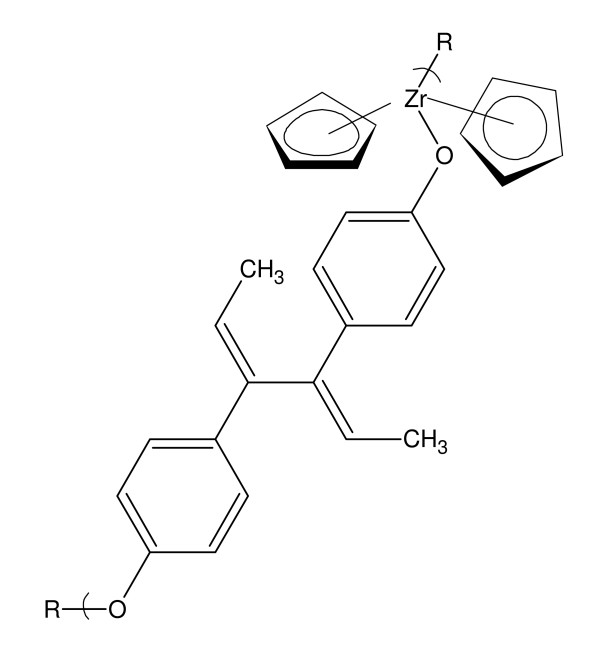

The topic of metallocene polymers has been recently reviewed [18]. We have described the synthesis and ability to arrest the growth of various cells by a number of Group IVB metallocene-containing polymers [1,19-21]. Recently we described the synthesis of organotin polyethers derived from diethylstilbestrol, DES, and the ability of these polymers to arrest the growth of a number of cancer cell lines.4 See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Repeat unit for the polymer from the reaction of DES and diorganotin dihalides.

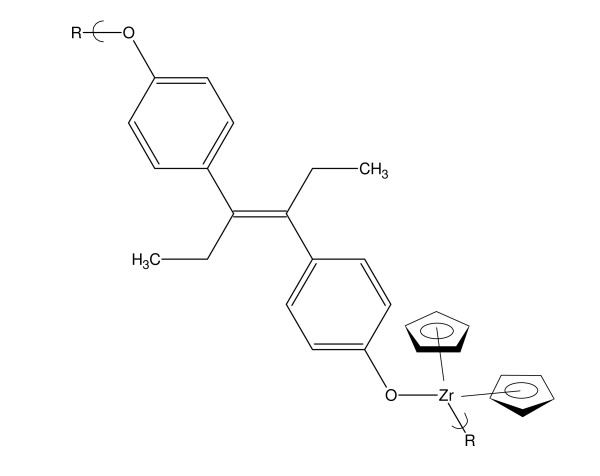

We also recently described the synthesis and ability to arrest the growth of various cell lines for the analogous polyethers derived from Group IVB metallocene dichlorides.

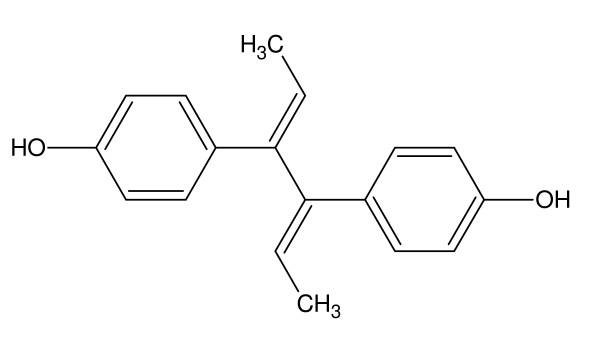

Dienestrol,(4- [4-(hydroxyphenyl)hexa-2,4-dien-3-yl]phenol, is one of the most widely utilized sex hormones. It was initially synthesized in 1939 and initially patented by both Boots and Hoffman-La Roche in 1949 [22,23]. In the popular literature it is often confused with DES, diethylstilbestrol, but it is a distinct hormone with its own chemical and biological properties. It is sold under a variety of tradenames including Farmacyrol, Lipamone, and Retalon-Oral.

Dienestrol is widely used in hormone therapy, mainly hormone replace therapy or more precisely, estrogen replacement therapy. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Repeat unit for the polymer from the reaction of DES and zirconocene dichloride.

Interestingly, little work has been done with respect to incorporating dienestrol into polymers either through the double bonds or through the diol moiety. Most of the current efforts with respect to polymers involve the synthesis of dienestrol, and similar drugs, employing covalent molecular imprinting [24-29] Additional work has focused on the controlled release of various steroids, including dienestrol, from various polymeric matrices [30-32]. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structure of dienestrol.

In 1956 a patent described the synthesis of antienzymic polymeric materials from the reaction of various diols including dienestrol from reaction with phosphoric and thiophosphoric acid [33]. It is not clear that any characterization of the product occurred since it was simply one of about 30 diol, diamine, and alcohol-amine-containing Lewis bases included in the patent.

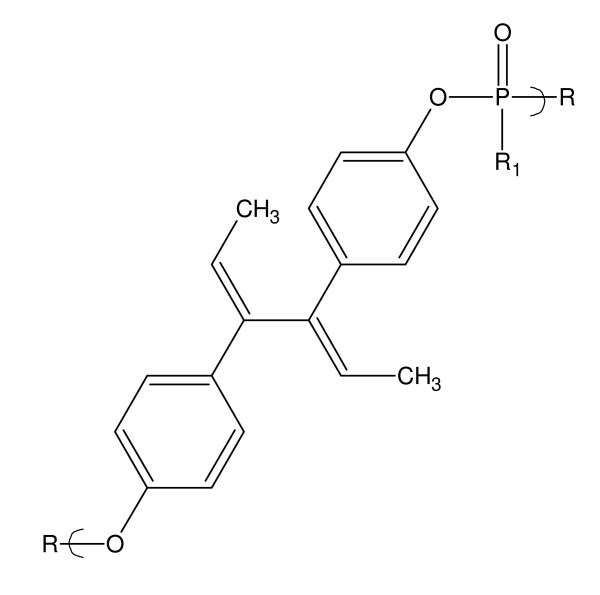

More recently, we described the synthesis of various polyphosphate and polyphosphate esters from the reaction of phosphorous acid chlorides with dienestrol [34].

About three decades ago we initially synthesized metallocene polyethers including a number of polyethers containing the titanocene, [35-37] zirconocene, [38] and hafnocene units [39]. This effort was recently reviewed [18]. There were a number of reasons for our synthesis of these materials including their use to control high energy radiation, as permanent coloring agents, and as potential anticancer agents [18]. Activity has recently increased in the use of metallocene-containing compounds in the treatment of cancer [40-52]. Much of this effort has focused on the use of titanocene-containing compounds. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Repeat unit for the polymer from the reaction of dienestrol and phosphorus acid chlorides.

Here we describe the synthesis of Group IVB metallocene polyethers based on the reaction of the Group IVB metallocene dichloride and dienestrol (Figure 5) and preliminary results with respect to their ability to arrest the growth of selected cancer cell lines. The advantages of employing polymeric drugs has been recently reviewed [16,53-55].

Figure 5.

Repeat unit for the polymer from the reaction of dienestrol and zirconocene dichloride, M = Zr.

Methods

Synthesis and Physical Characterization

Polymerization was accomplished employing the classical or aqueous interfacial polycondensation system. Briefly, an aqueous solution (30 mL) containing the dienestrol (0.00300 mol) and sodium hydroxide (0.0060 mole) was transferred to a one quart Kimax emulsifying jar fitted on top of a Waring Blender (model 1120; no load speed of about 18,000 rpm; reactions were carried out at about 25°C). Stirring was begun and a chloroform solution (30 ml) containing the metallocene dihalide (0.00300 mol) was rapidly added (about 3-4 seconds) through a hole in the jar lid using a powder funnel. The resulting solution was blended for 15 seconds. The precipitate was recovered using vacuum filtration and washed several times with deionized water and chloroform to remove unreacted materials and unwanted by-products. The solid was washed onto a glass petri dish and allowed to dry at room temperature.

Chain length was determined employing light scattering photometry using a Brice-Phoenix BP 3000 Universal Light Scattering Photometer. Refractive indicies were obtained using a Bauch & Lomb Model 3-L refractometer. FTIR spectra were obtained employing KBr pellets using a Mattson Instruments galaxy Series 4020 FTIR using 32 scans and an instrumental resolution of 4 cm-1.

High resolution electron impact positive ion matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight, HR MALDI-TOF, mass spectrometry was carried out employing a Voyager-DE STR BioSpectrometer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA. The standard settings were used with a linear mode of operation and an accelerating voltage of 25,000 volts; grid voltage 90% and an acquisition mass range of 100 to 2,000 daltons. Two hundred shots were typically taken for each spectrum. Several matrix materials were employed but here only results employing α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid are included for the hafnocene and zirconocene products and the matrix 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid for the titanocene product.

Biological Characterization

Each of the cell lines listed in Table 1 were obtained from NCI or ATCC and maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere.

Table 1.

Product yield and molecular weight as a function of metallocene.

| Metallocene | % Yield | dn/dc | Mw | DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titanocene | 43 | -3.5 | 3.3 × 107 | 70,000 |

| Zirconocene | 42 | -1.0 | 6.7 × 106 | 14,000 |

| Hafnocene | 47 | -0.40 | 2.1 × 105 | 400 |

Note. While the solubility in DMSO is too low to permit NMR and LS in DMSO it is sufficient to allow for biological testing employing DMSO stock solution.

For testing of the compounds, cells were harvested, counted, and plated into 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells per well in MEM-Eagles supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. A stock solution of the compound was prepared in DMSO at a known concentration. On day two 100 μL MEM-Eagles supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and the indicated drug concentrations was added. Seventy-two hours later the cells were assayed for proliferation using the CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay by Promega Corporation. The assay is a colorimetric method for determining the number of viable cells in proliferation, cytotoxicity or chemosensitivity assays. The assay solution contains a tetrazolium compound [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt; MTS(a)] and an electron coupling reagent (phenazine ethosulfate; PES). Assays are performed by adding a small amount of the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Reagent directly to culture wells, incubating for 1-4 hours and then recording absorbance at 490 nm with a 96-well plate reader. The quantity of formazan product as measured by the amount of 490 nm absorbance is directly proportional to the number of living cells in culture.

All cytotoxicity values are calculated against a base-line value for each line that was generated from "mock-treatment" of the normal and tumor cells lines with media supplemented with all diluents used to prepare the chemotherapeutic compounds. For example, if the compounds were dissolved in DMSO and serial dilutions prepared in MEM to treat the cells, then the mock-treated cells were "treated" with the same serial dilutions of DMSO without added chemotherapeutic compound. This was done to ensure that any cytotoxicity observed was due to the activity of the compound and not the diluents. For the studies reported here, the mock-treatment never resulted in a loss of cell viability of more than one percent, demonstrating that the activity observed was not due to cytotoxicity of any of the diluents used, but was due to activity of the tested compounds.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

The products were synthesized in average yields in the same range as found for the synthesis of the analogous products except employing DES as the diol in place of dienestrol (Table 1).

The polymers are not soluble in DMF, acetone, and DMF, all solvents that typically dissolved other similar organometallic condensation polymers, and only partially soluble in DMSO. In comparison to the analogous organotin-diethylstilbestrol products, the Group IVB metallocene products have poorer solubilities. This trend is found for other polymers synthesized by us where the metallocene-containing polymers exhibit poor solubility in comparison to the analogous organotin polymers.17 The products are soluble in HMPA. Results appear in Table 1. The products are medium to long chained products.

The products from titanocene and zirconocene are stable in HMPA solution for three months whereas the hanfocene product was stable for 2 months and at month three there was a modest loss in molecular weight from 2.1 × 105 to 1.7 × 105.

Infrared spectral results are consistent with the proposed repeat unit. Only selected bands will be described here. Here we will concentrate on the IR spectra from the titanocene product. The dienestrol-associated O-H stretch occurs with a maximum at 3415 (all bands given in cm-1). It is the most intense band in the spectrum of dienestrol. Dienestrol shows bands due to the aromatic C-H at 3026 and 3005 and aliphatic C-H bands at 2972, 2933, 2910, and 2852. Titanocene dichloride shows a band at 3103 assigned to C-H aromatic stretching. The product shows bands at about 3100, 3027, 3005, 2972, 2910, and 2854. The locations of bands associated with the Ti-O are reported to be about 345 for the symmetric stretch and 420 for the asymmetric stretch. The presence of a new band at 440 is assigned to the Ti-O asymmetric stretch. The 345 band is below the capability of the employed instrument. Other titanocene dichloride, dienestrol, and metallocene polymer-associated bands and assignments are given in Table 2. Thus, IR spectral results are consistent with the proposed structure.

Table 2.

Vibrational band assignments for titanocene dichloride and the products of Group IVB metallocene dichlorides and dienestrol

| Mode | Dien | Cp2TiCl2 | Ti-Polymer | Zr-Polymer | Hf-polymer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH Stretch | 3415 | ||||

| CH St. Ar | 3026,3005 | 3103 | 3100,3027, 3091 | 3100, 3027, 3005 | 3069, 3029, 3005 |

| CH St. Alip | 2972, 2933, 2910, 2852 | 2972, 2910, 2852 | 2970, 2912, 2854 | 2970, 2912, 2866 | |

| C = C St. Alip | 1641 | 1651 | 1650 | 1650 | |

| C = C St. Ar | 1603 | 1608 | 1604 | 1606 | |

| Phenylene Ske | 1504 | 1500 | 1506 | 1501 | |

| (Cp) CC St | 1440 | 1425 | 1423 | 1426 | |

| C-O St | 1419 | 1389 | 1390 | 1425 | |

| CC Stretch | 1364 | 1330 | 1331 | 1333 | |

| CH i.p. Bend | 1238 | 1243 | 1244 | 1246 | |

| Ring Breathing | 1166 | 1171 | 1171 | 1171 | |

| CH o.p. Bend | 1093 | 1099 | 1099 | 1101 | |

| C-C St | 1062 | 1040 | 1040 | 1040 | |

| CH i.p. Bend | 1015 | 1012 | 1014 | 1014 | |

| CC i.p. Bend | 949 | 956 | 952 | 955 | |

| CH o.p. Bend | 892 | 902 | 900 | 854 | |

| CH o.p. Bend | 820 | 829 | 827 | 828 | |

| CH2 Rocking | 740 | 740 | 740 | 721 | |

| CC o.p. Bend | 613 | 617 | 619 | 619 |

A modified MALDI MS analysis was carried out on the products and reactants [55,56] The most intense ion fragment for dienestrol itself was found at 265 (all ion fragments are given in m/z or m/e = 1 in Daltons) assigned to dienestrol. The next intense was at 212 assigned to dienestrol minus 2 C2H4.

For brevity, only the results for the titanocene products will be described. Table 3 contains the ion fragments and ion fragment clusters found for the product of titanocene dichloride and dienestrol in the range of 100 to 1,000 daltons.

Table 3.

Most abundant ion fragment clusters for the product from titanocene dichloride and dienestrol; 100 to 1,000 Da.

| m/e | (Proposed) Assignment | m/e | (Proposed) Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 129 | CpTiO | 193 | Cp2TiO |

| 266 | D | 289 | D, Na |

| 313 | U-A | 529 | U+A, O-Cp |

| 551 | U+B-Cp | 573 | U+B |

| 643 | U+Cp2TiO | 706 | U+D |

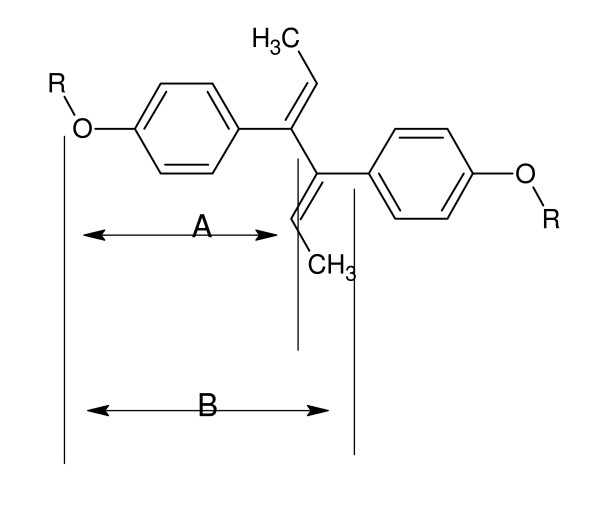

A number of abbreviations are employed to describe the possible ion fragment structures. Some of these are described in Figure 6 below. Additional ones are U = one units; 2 U = 2 units, D = dienestrol, Me = methylene, and Ph = phenylene.

Figure 6.

Fragmentation of dienestrol moiety for MALDI MS fragmentation identification.

There is some loss of the cyclopentadienyl, Cp, group. This is not unexpected in light of other MS studies that show that metallocene associated Cp groups are especially sensitive to removal from the metallocene moieties [18].

Titanium has five isotopes. This allows isotopic abundance matches to be made. Table 4 contains the isotopic matches for two of these ion fragment clusters. The abundance matches are reasonable and consistent with the presence of one titanium in each ion fragment cluster.

Table 4.

Isotopic abundance matches for ion fragment clusters centering about 529 and 551 daltons.

| U+A, O-Cp | U+B-Cp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/e | % Nat Abu | m/e | % Rel Abun | m/e | % Rel Abu |

| 46 | 11 | 527 | 11 | 549 | 12 |

| 47 | 10 | 528 | 10 | 550 | 11 |

| 48 | 100 | 529 | 100 | 551 | 100 |

| 49 | 7 | 530 | 7 | 552 | 8 |

| 50 | 7 | 531 | 5 | 553 | 7 |

Table 5 contains the ion fragment clusters found in the range of 10,000 to about 150,000 along with possible assignments. These assignments are to be viewed as suggestive only. This is particularly true because of the ready removal of the Cp group. In other cases such removals occur at only the sites of bond scission so the loss of one or two Cp groups is believed to be typical.

Table 5.

MALDI MS Results for the mass range of 10,000 to 160,000 Da for the product of titanocene dichloride and dienestrol.

| m/e | (Possible) Assignment | m/e | (Possible) Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10823 | 24U+Cp2TiO | 11172 | 25U+B-Cp |

| 11568 | 26U+A-Cp | 13070 | 30U-Cp2TiO |

| 15692 | 35U+Cp2TiO | 16750 | 38U-Cp |

| 17068 | 39U-Cp2Ti | 21940 | 50U-Cp2Ti |

| 22219 | 50U+A-OMe | 28310 | 64U |

| 28863 | 65U+Cp2Ti | 32027 | 72U+Cp2Ti |

| 38381 | 87U-OPh | 44590 | 101U-OPh |

| 48138 | 109U-OPh | 49238 | 111U-A |

| 49569 | 112U+O | 56009 | 127U-Cp2Ti |

| 56959 | 129U-O | 59220 | 134U-Cp |

| 67201 | 152U-Cp+O | 84377 | 191U-2Cp+O |

| 88777 | 201U-A | 94899 | 214U+D-O |

| 116850 | 264U+A-Cp | 130742 | 296U-Cp2TiO |

| 141309 | 319U+Cp2TiO | 142044 | 321U |

| 154454 | 349U+A-Cp |

The presence of these high mass ion fragments is consistent with the polymeric nature of the tested material. A number of these ion fragments may be entire chains such as those at 17068, 21940, 22219, 28310, 49238, 56009, 88777, and 142044 consistent with the "soft" nature of MALDI MS.

The results are consistent with other studies where chain scission occurs mainly at the heteroatoms. They are also consistent with the assigned product structure.

Cell Line Results

The tested cell lines represent a wide range of cancers including breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancer cell lines (Table 6). They also include two "normal" cell lines, the WI-38 human cells which are typically employed as a normal cell line in such studies, and 3T3 cells that are mouse cells that are partially transformed. Both of these cell lines are often employed as examples of healthy cell lines and the results from them are compared to results from the various cancer cell lines giving measures of the ability of the tested drug to differentiate between healthy and cancer cell lines. Of the two, the WI-38 is more widely employed as representative of a healthy cell line for such comparisons. Also included in the test samples is cisplatin, a widely employed anticancer drug, as a comparison to a known anticancer agent.

Table 6.

Cell line Characteristics and Identification

| Strain | NCI/ATCC designation | Species | Tumor orgin | Histological type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3465 | PC-3 | Human | Prostate | Carcinoma |

| 7233 | MDA MB-231 | Human | Breast pleural effusion | Adenocarcinoma |

| 1507 | HT-29 | Human | Colon recto-sigmoid | Adenocarcinoma |

| 7259 | MCF-7 | Human | Breast pleural effusion | Adenocarcinoma |

| CCL-75 | WI-38 | Human | Lung normal embryonic | Fibroblast |

| CRL-1658 | NIH 3T3 | Mouse | Continuous cell line of highly contact-inhibited cells | Embryo-fibroblast |

Different measures are employed in the evaluation of cell line results. Here we use the two most widely employed- GI50 values which is the lowest concentration where growth is inhibited by 50% and the Chemotherapeutic Index, CI50 which is a measure of the amount needed to inhibit 50% cell growth, GI50, for the normal cell lines, here WI-38 and 3T3 cell lines, divided by the amount needed to inhibit 50% cell growth for one of the cancer cell lines. It is to be noted that different researchers generally emphasize one of these measures over the other with neither measure universally accepted. Thus, results from both of these measures are presented. [see Additional file 1: Table S1] contains the GI50 values for the polymers, DES, and cisplatin.

The GI50 values for the polymers are significantly lower than for cisplatin with the exception of the WI-38 healthy cells. The GI50 values for the metallocene monomers are much higher than for the analogous polymers. They are in the general range of the dienestrol itself. Further, with respect to the polymers the breast cancer cell line without estrogen (MDA MB-231) showed better test results than the breast cancer cell line that is positive for estrogen (MCF-7) perhaps because some of the drug is bound to the estrogen receptors and not available to act within the cell. This is consistent with the finding that DES is effective against estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors [57,58].

The second measure is the 50% chemotherapeutic index, CI50. When describing the CI some researchers employ the similar terms ED or effective dose in place of the GI value for the cancer cells and LD or lethal dose in place of GI for the healthy cell line, here the WI-38 cell line. Thus, CI50 = LD50/ED50. Larger values are desired since they indicate that a larger concentration is required to inhibit the healthy cells in comparison to the cancer cells or stated in another way, larger values indicate some preference for inhibiting the cancer cells in preference to the normal cells. In general, CI50 values larger than 2 are considered significant. CI50 values are given in [see Additional file 2: Table S2].

An additional question concerns the influence of simply having the metallocene moiety present in a polymer. [see Additional file 3: Table S3] contains the CI50 values normalized against the CI50 value for dienestrol. This ratio may offer some measure of the effectiveness of having the two monomer moieties within the polymer. Values greater than one would be consistent with the presence of that moiety present in the polymer having a favorable effect.

Conclusion

Several features are apparent. First, cisplatin, while a most widely employed anticancer drug, has small CI50 values, all 0.02 and lower. Second, the metallocene dichlorides all have low CI50 values. Third, dienestrol has two CI50 values greater than two. Thus, it shows some significant ability to inhibit the cell growth of the transformed, 3T3, and one cancer drug in comparison to the concentration where the healthy WI-38 cell line is not affected. Third, the metallocene polymers all exhibit some CI50 values above 2. The hafnocene and zironocene-dienestrol polymers exhibit high CI50 values for all of the tested cancer and transformed cell lines. This is consistent with these particular polymers meriting further study. Further, while much of the recent anticancer effort with respect to metallocene-containing compounds has focused on titanocene-containing compounds, the zirconocene and hafnocene polymers showed somewhat better CI50 values in the current study. Thus, future studies might consider not only the titanocene-containing compounds but also the analogous zirconocene and hafnocene compounds for study. Fourth, while the dienestrol exhibited decent CI50 values, all of the corresponding polymers exhibited higher CI50 values for all of the cell lines. Thus, the ability to arrest cell growth is not only dependent on the presence of the dienestrol but also on the presence of the metallocene moiety.

With respect to the normalization of the CI50 values for each cell line against the CI50 values for dienestrol itself, no norm has been established for this kind of comparison. Thus, conclusions should be viewed in this light. All of the values for the polymers are greater than two consistent with the presence of having the combination of dienestrol and metallocene in the same polymer being positive with respect to the ability to inhibit cancer and transformed cells in comparison to the healthy WI-38 cell line.

The current drugs also offer several addition positive aspects. First, the reactants are commercially available so that additional synthetic steps are not needed. Second, synthesis of the polymer is rapid, occurring within about 15 seconds. Third, the interfacial synthetic system is already industrially employed in the synthesis of aromatic nylons and polycarbonates. Thus, the ability to synthesize large amounts of the drugs is straight forward.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YA, GB and CC synthesized a new series of metallocene-containing compounds and preformed the light scattering photometry, the matrix assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy. KS and MR carried out all the in vitro antitumor activity assays. MR and CC participated in the design of the study and KS performed the statistical analysis. MR and CC conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Table S1. GI50 concentrations (μg/mL) for metallocene polyethers for tested cell lines [a]. [a]The data shown here are the average from three independent experiments, with the standard deviations shown in ().

Table S2. CI50 concentrations (μg/mL) for metallocene polyethers for tested cell lines [a]. [a]The data shown here are the average from three independent experiments, with the standard deviations shown in ().

Table S3. CI50 concentrations (mg/mL) for the Samples for Each Cell Line Normalized Against Values for Dienestrol.

Contributor Information

Michael R Roner, Email: roner@uta.edu.

Charles E Carraher, Jr, Email: carraher@fau.edu.

Kimberly Shahi, Email: krshahi@gmail.com.

Yuki Ashida, Email: ashida.yuki@gmail.com.

Girish Barot, Email: girishbarod@yahoo.com.

References

- Carraher C. Organotin polymers, in Macromolecules Containing Metal and Metal-Like Elements, Group IVB-ContainingPolymers. Vol. 4. Wiley, Hobokin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Li F, Butler C. Synthesis and structural characterization of polymers derived from the condensation of organotin dichlorides and the synthetic amino acids p-amonobenzoic acid and ampicillin. J Polym Mater. 2000;17:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Lanz L. Synthesis and initial structural characterization of organotin polymers containing norfloxacin. J Polym Mater. 2003;20:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Roner MR, Shahi K, Ashida Y, Barot G. Synthesis and initial cell line results of organotin polyethers containing diethylstilbestrol. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2008;18:180–188. doi: 10.1007/s10904-007-9184-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barot G, Shahi K, Roner M, Carraher C. Synthesis, structural characterization, and ability to inhibit cancer growth of a series of organotin poly(ethylene glycols) Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2007;17:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s10904-007-9158-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Morie K. Synthesis of organotin polyesters containing ticarcillin. J Polym Mater. 2004;21:383–391. [Google Scholar]

- Barot G, Shahi K, Roner M, Carraher C. Synthesis, anomalous fiber formation, and preliminary anticancer study of the organotin polyether derived from 2-butyne-1,4-diol. J Polym Mater. 2006;23:423–436. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Morie K. Organotin polyesters from 1,1'-ferrocenedicarboxylic acidO. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2007;17:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10904-006-9089-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Battin A, Shahi K, Roner M. Synthesis, structural characterization, and initial evaluation as anticancer drugs of dibutyltin polyamines derived form various 4,6-diaminopyrimidines. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2007;17:631–639. doi: 10.1007/s10904-007-9159-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Sabir T, Roner M, Shahi K, Bleicher R, Roehr J, Bassett K. Synthesis of organotin polyamine ethers containing acyclovir and their preliminary anticancer and antiviral activity. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2006;16:249–257. doi: 10.1007/s10904-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roner M, Carraher C, Roehr J, Bassett K. Antiviral and anticancer activity of organotin polymers and reactants derived from norfloxacin and ampicillin. J Polym Mater. 2006;23:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher CE, Jr, Roner MR, Barot G. Organotin-containing Polyethers as Potential Anticancer Drugs. Cancer Research Journal. 2009. in press .

- Roner M, Carraher C, Dhanji S, Barot G. Antiviral and anticancer activity of cisplatin derives of tilorone. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2008;18:374–383. doi: 10.1007/s10904-008-9219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roner M, Carraher C, Dhanji S, Barot G. Antiviral and anticancer activity of cisplatin derivatives of methotrexate. J Polym Mater. 2007;24:371–385. doi: 10.1007/s10904-008-9219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Scott W, Schroeder J. Poly(cis-dihalodiamineplatinum(II)) compounds: synthesis and biological activity. J Macromol Sci Chem. 1981;A15:625–631. doi: 10.1080/00222338108056754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmann-Louda D, Carraher C. Polymeric platinum-containing drugs in the treatment of cancer, in Macromolecules Containing Metal and Metal-Like Elements. Biomedical Applications. Vol. 3. Wiley, Hobokin; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Lopez I, Giron D. Polymeric platinol derivative of methotrexate for the treatment of virally related juvenile diabetes. New York, NY: Plenum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C. Condensation metallocene polymers. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymer Materials. 2005;15:121–145. doi: 10.1007/s10904-004-2382-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir T, Carraher C. Synthesis and structural characterization of group IVB metallocene polymers containing acyclovir. J Polym Mater. 2005;22:449–458. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C. Organotin polymers, in Macromolecules Containing Metal and Metal-Like Elements, Group IVA Polymer. Vol. 4. Wiley, Hobokin; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher CE, Roner MR, Shahi K, Ashida Y, Barot G. Synthesis, structural characterization, and anti-cancer evaluation of group IVB-metallocene polyethers containing the synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol. J Polym Mater. 2007;24(4):357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Short WF, Hobday GI. Dienestrol. US, 2,464,203: Boots. 1949.

- Adler E. 3,4-Bis(p-hydroxphenol)-2,4-hexadiene. US Pat. 2,465,505: Hoffman-La Roche. 1949.

- Ikegami T, Mukawa T, Nariai H, Takeuchi T. Bisphenol A-recognition polymers prepared by covalent molecular imprinting. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;504(1):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2003.08.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami T, Lee WS, Nariai H, Takeuchi T. Covalent molecular imprinting of bisphenol A using its diesters followed by the reductive cleavage with LiAlH4. J Chromatogr B. 2004;804(1):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanbe H, Haginaka J. Uniformly sized molecularly imprinted polymers for bisphenol A and beta-estradiol: retention and molecular recognition properties in hydro-organic mobile phases. J Pharmaceut Biomed. 2003;30(6):1835–1844. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Yu YH, Mosbach K. Towards the development of molecularly imprinted artificial receptors for the screening of estrogenic chemicals. Analyst. 2001;126(6):760–765. doi: 10.1039/b009048o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbin JA, Sharman M. Development of molecularly imprinted phase for the selective retention of stilbene-type estrogenic compounds. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;433(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)01373-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbin JA, Sharman M. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of a molecularly imprinted polymer selective for artificial phenolic estrogenic compounds. Anal Commun. 1999;36(3):105–107. doi: 10.1039/a900197b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaya N, Karen R, Sadanand S, Gupta V. Novel dosage form comprising modified-release and immediate-release active ingredients. Office USP, vol. US 2006024365. USA; 2006. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Ai H, Duerk J, Flask C, Gao J, Lewin J, Shuai X, Weinberg B. Dual function polymer micelles used for drug delivery and contrast agents. Office USP, vol. US 2004-577142 20040604. USA; 2005. p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan M, Krishnan A, Sapre B, Shan C, Patil A. Controlled release pharmaceutical compositions containing polymers. Office USP, vol. US 2003-517589 20031105. USA; 2004. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Aktiebolaget L. In: High-molecular, phosphorus-containing antienzymic substances. Britain G, editor. vol. GB 753319. Great Britain; 1956. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Powers D, Pandya B. Synthesis and structural characterization of polyphosphate and polyphosphonate esters derived from biologically active diols. J Polym Mater. 1993;10:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Bajah S. Effects of base nature, base concentration, and method of synthesis of titanium polyether. British Polymer Journal. 1975;7:155–159. doi: 10.1002/pi.4980070304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Bajah S. Tentative identification of reactive species in the interfacial and aqueous solution synthesis of titanium polymers. Polymer. 1974;15:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(74)90067-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Bajah S. Synthesis of titanium polyethers by the interfacial and aqueous solution techniques. Polymer. 1973;14:42–44. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(73)90093-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Jambaya L. Synthesis of zirconium polyethers. Die Angew Makromol Chemie. 1974;39:69–76. doi: 10.1002/apmc.1974.050390106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Jambaya L. Initial synthesis and thermal characterization of hafnium polyethers. Die Angew Makromol Chemie. 1976;52:111–116. doi: 10.1002/apmc.1976.050520110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pampillion C, Sweeney N, Strohfeldt K, Ttacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of new dimethylamino-functionalized and heteroaryl-substituted titanocene anti-cancer drugs. Journal of Organomatallic Chemistry. 2007;692:2153–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2007.01.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oberschmidt O, Hanauske A, Pampillon C, Sweeney N, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of new dimethylamino-functionalized and heteroaryl-substituted titanocene anti-cancer drugs. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2007;18:317–321. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3280115f86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Lu C, Ren X, Meng Q. New metallocene-bridged cyclodextrin dimer: a stable derivative of the antitumor drug titanocene dichloride and its potent cytoxicity against human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. Journal of Organomatallic Chemistry. 2006;691:5895–5899. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.09.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potter G, Baird M, Chan M, Cole S. Cellular toxicities of new titanocene dichloride derivatives containing pendant cyclic alkylammonium groups. Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 2006;9:1114–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2006.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Ruiz S, Kaluderovic GN, Prashar S, Polo-Ceron D, Fajardo M, Zizak Z, Sabo TJ, Juranic ZD. Cytotoxic studies of substituted titanocene and ansa-titanocene anticancer drugs. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2008;102(8):1558–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claffey J, Hogan M, Muller-Bunz H, Pampillon C, Tacke M. Oxali-titanocene Y: A potent anticancer drug. Chemmedchem. 2008;3(5):729–731. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansauer A, Winkler I, Worgull D, Lauterbach T, Franke D, Selig A, Wagner L, Prokop A. Carbonyl-substituted titanocenes: A novel class of cytostatic compounds with high antitumor and antileukemic activity. Chem-Eur J. 2008;14(14):4160–4163. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez R, Lamboy J, Gao LM, Matta J, Roman FR, Melendez E. Structure-activity studies of Ti(IV) complexes: aqueous stability and cytotoxic properties in colon cancer HT-29 cells. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2008;13(5):685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Bioorganometallic fulvene-derived titanocene anti-cancer drugs. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37(6):1174–1187. doi: 10.1039/b707310k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling CM, Claffey J, Cuffe S, Fichtner I, Pampillon C, Sweeney NJ, Strohfeldt K, Watson RWG, Tacke M. Antitumor activity of Titanocene Y in xenografted PC3 tumors in mice. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2008;5(2):141–144. doi: 10.2174/157018008783928463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pampillon C, Claffey J, Hogan M, Tacke M. Novel achiral titanocene anti-cancer drugs synthesised from bis-N,N-dimethylamino fulvene and lithiated heterocyclic compounds. Biometals. 2008;21(2):197–204. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan M, Claffey J, Pampillon C, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of new morpholino-functionalised and N-heteroaryl-substituted titanocene anticancer drugs. Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;4(2):91–99. doi: 10.2174/157340608783789202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampillon C, Claffey J, Strohfeldt K, Tacke M. Synthesis and cytotoxicity studies of new dimethylamino-functionalised and aryl-substituted titanocene anti-cancer agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;43(1):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twaites B, Alarcon CD, Alexander C. Synthetic polymers as drugs and therapeutics. J Mater Chem. 2005;15(4):441–455. doi: 10.1039/b410799n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia MK, Jain SK. Design and development of multiparticulate system for targeted drug delivery to colon. Drug Delivery. 2004;11(3):201–207. doi: 10.1080/10717540490445955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Sabir T, Carraher CL. Fundamentals of Fragmentation Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher C, Sabir T, Carraher CL. Fragmentation Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry-Basics. J Polym Mater. 2006;23:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Swain S, Lippman M. Cancer Chemotherapy. Philadelphia, PA.: Liopincott; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzang N. Chemotherapy Source Book. Vol. 1008. Maryland: Williams & Wilkins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. GI50 concentrations (μg/mL) for metallocene polyethers for tested cell lines [a]. [a]The data shown here are the average from three independent experiments, with the standard deviations shown in ().

Table S2. CI50 concentrations (μg/mL) for metallocene polyethers for tested cell lines [a]. [a]The data shown here are the average from three independent experiments, with the standard deviations shown in ().

Table S3. CI50 concentrations (mg/mL) for the Samples for Each Cell Line Normalized Against Values for Dienestrol.