Abstract

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that is critically important to the loading patterns within the knee joint. If the meniscus structure is compromised, there is little chance of healing due to limited vascularity in the inner portions of the tissue. Several tissue engineering techniques to mimic the complex geometry of the meniscus have been employed. Of these, a self-assembly, scaffoldless approach employing agarose molds avoids drawbacks associated with scaffold use while still allowing formation of robust tissue. In this experiment two factors were examined, agarose percentage and mold surface roughness, in an effort to consistently obtain constructs with adequate geometric properties. Co-cultures of ACs and MCs (50:50 ratio) were cultured in smooth or rough molds composed of 1% or 2% agarose for 4 wks. Morphological results showed that constructs formed in 1% agarose molds, particularly smooth molds, were able to maintain their shape over the 4 wk culture period. Significant increases were observed for the collagen II to collagen I ratio, total collagen, GAG, and tensile and compressive properties in smooth wells. Cell number per construct was higher in the rough wells. Overall, it was observed that the topology of an agarose surface may be able to affect the phenotypic properties of cells that are on that surface, with smooth surfaces supporting a more chondrocytic phenotype. In addition, wells made from 1% agarose were able to prevent construct buckling potentially due to their higher compliance.

Keywords: Co-cultures, agarose, knee meniscus, tissue engineering, scaffoldless, mold, compliance, roughness

1. Introduction

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue that is situated between the femur and tibia within the knee joint. Due to its location, geometry, and composition, the meniscus protects the underlying articular cartilage from excessive stresses via force distribution and shock absorption (Jones et al. 1996; Kurosawa et al. 1980). However, if the meniscus structure is compromised, its ability to perform these critical functions is lost (Casscells 1978; Fairbank 1948). Furthermore, injuries to the inner regions of the meniscus do not heal due to limited vascularity in that region. Partial meniscectomy is the most common treatment for meniscal tears and can alleviate short term symptoms of pain and temporarily restore joint function (Stone 1999). In the long term, the loss of meniscal cartilage leads to degeneration of the underlying articular cartilage and quickens the onset of osteoarthritis (Cox et al. 1975). Thus, tissue engineering may be a viable option to repair or replace injured tissue.

The meniscus contains a heterogeneous cell and ECM population (McDevitt et al. 1992). The inner region contains chondrocyte-like cells and the ECM is composed of a network of collagen II and collagen I fibers in a 3:2 ratio, and the proteoglycan aggrecan. In vivo, the inner meniscus is loaded with an axial compressive force. The outer region contains fibroblast-like cells with circumferentially oriented collagen I fibers. Due to the wedge-shaped profile and attachments of the meniscus, the compressive load experienced by the inner meniscus is partially converted into circumferential tensile forces in the outer regions. Furthermore, the wedge-shaped profile of the meniscus corrects the incongruity between the curved femoral condyles and flat tibial plateau allowing distribution of the compressive forces over a larger area of the articular surfaces (Fithian et al. 1990; Radin et al. 1984). Finite element models have shown that geometrical aspects of the meniscus, particularly the radius of curvature to match the femoral condyle, are critically important to the ability of the meniscus to absorb and distribute loading (Meakin et al. 2003). Thus, for an engineered meniscal substitute, recapitulation of geometry and composition will be critical to achieve successful tissue replacement.

Most attempts at creating meniscus-shaped constructs have involved producing scaffolds by pouring a liquid polymer solution into a mold and allowing it to set or by adding a cross-linking agent (Ballyns et al. 2008; Chiari et al. 2006; Martinek et al. 2006). Other attempts have used solid freeform fabrication (Cohen et al. 2006) or physical shaping (Kang et al. 2006). These attempts at shape-mimicking have highlighted a number of issues that must be addressed before a meniscus-specific construct can be realized, including shape retention and obtaining adequate biochemical and biomechanical properties.

Although widely used in tissue engineering studies, scaffold materials can present several drawbacks. These include toxicity associated with scaffold degradation byproducts, lack of cellular mechanotransduction due to stress shielding, and irregular tissue ingrowth to scaffold degradation rates (Hu and Athanasiou 2006). A self-assembly, scaffoldless approach developed in our laboratory circumvents these issues, and allows for the creation of shape-specific geometries. Previous work with this approach has shown that meniscus cells (MCs) and articular chondrocytes (ACs) can be co-cultured in ring-shaped molds (Aufderheide and Athanasiou 2007). However, with increasing AC percentage, the constructs expand radially, contact the well edge and slide up the smooth wells or buckle in response to the force placed on the construct by the agarose well. With increasing MC percentage the constructs contract into a torus. Thus, by using various ratios of the two cell types, the expansive contribution of ACs and contractile contribution of MCs can be modulated to form different shaped constructs.

Utilizing data from a previous study (Aufderheide and Athanasiou 2007), and from pilot studies in the laboratory, it has been determined that a 50:50 co-culture ratio of ACs and MCs, grown in a ring-shaped mold, in the presence of serum most closely resembles the native meniscus. However, when switching to a serum-free approach, enhanced expansive growth is noted as the constructs expand radially (Hoben and Athanasiou 2008). To address this issue, the compliance of the agarose well was studied to determine if a well that provided less resistance to construct impingement would allow for proper construct geometry. To this end, two different agarose percentages (1% and 2%) were examined. In addition, topology of the well walls was also altered (rough and smooth wells) to examine whether roughness would prevent buckling of the constructs by increasing the frictional contact between the radially expanding constructs and the well wall. It was hypothesized that 1) buckling would be reduced by increased compliance of lower agarose-content (1%) wells; and 2) buckling would be reduced by increased frictional contact in wells with rough edges.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Mold-maker fabrication

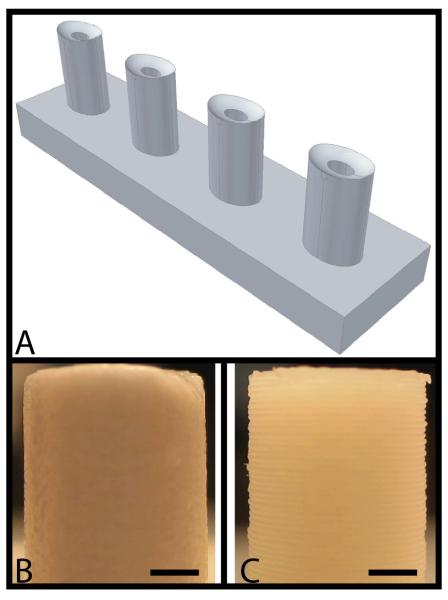

Pictures of rabbit medial menisci were taken to obtain meniscus geometric properties and scanned into AutoCAD 2007 (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA). Using this information, a mold-maker drawing was created that captured the negative of the elliptical shape and the curved, wedge profile observed in the meniscus (Figure 1A). The AutoCAD drawings were then imported to a solid freeform fabrication machine that created the part.

Figure 1.

Meniscus mold-maker. (A) AutoCAD drawing of the mold-maker (negative of the idealized meniscus shape) (B) Mold-maker fabricated with smooth topology using a ZPrinter 310 rapid prototyping machine (scale bar = 2 mm). (C) Mold-maker fabricated with rough topology using a Dimension 768 SST rapid-prototyping machine (scale bar = 2 mm).

In order to obtain two types of mold-makers with similar geometrical properties but differing in surface roughness, two different solid-freeform fabrication machines were employed. To create the smooth mold-maker, a ZPrinter 310 (Z Corporation, Burlington, MA) was used. This machine employs 3D printing technology to place a drop of binding solution into a basin of powder to create a part with a layer thickness of 76 μm. Although the layer thickness alone was sufficient to obtain a smooth surface, the mold-maker was dipped in latex solution to ensure smoothness and to prevent agarose from infiltrating the porous material (Figure 1B). The rough mold-maker was created using a Dimension 768 SST (Stratasys, Eden Prarie, MN) which utilized fused deposition modeling technology to build the part layer by layer using a thin acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic cord (Figure 1C). This method of rapid prototyping imparted an inherent anisotropic roughness to the mold-maker due to the large layer thickness dictated by the use of a 245 μm diameter ABS cord. The average roughness value (Ra) was estimated based on the B46.1-2002 ASME standard by assuming the surface was a waveform composed of semi-circles with no gaps in between. Images of the surface of the mold-maker were analyzed using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) to determine the diameter of the semi-circular protrusions. The surface roughness, Ra, was measured using the following equation.

| (1) |

Y(x) is the function describing the surface of the mold-maker with the horizontal axis set midway between the highest and lowest amplitude of the waveform and L is the length over which roughness is measured. Roughness was not present in the direction corresponding to the long axis of the ABS cord but was present in both the horizontal and vertical directions emanating from the center of an individual elliptical mold-maker post.

2.2 Mold fabrication

Type VII agarose molds (1% and 2% w/v) were created by pouring molten agarose into the wells of a 24-well plate (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The mold-makers were placed into the molten agarose and left until the agarose hardened. The mold-makers were then removed and the resulting agarose molds were transferred to 12-well plates (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The molds represented the idealized geometry of the meniscus. Chemically-defined serum-free medium was allowed to infiltrate the molds for 4 days in an incubator before seeding. The medium consisted of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g/L-glucose and GlutaMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 100 nM dexamethasone, 1% fungizone (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), 1% ITS+ premix, 50 mg/mL ascorbate-2-phosphate, 40 mg/mL L-proline, and 100 mg/mL sodium pyruvate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

2.3 Cell isolation and seeding

The knee joints of skeletally immature calves (Research 87, Boston, MA) were dissected to obtain the medial menisci, and the tibial and femoral articular cartilage. In a cell culture hood, the vascular outer third of the meniscus was removed and the remainder was diced into small ~1mm pieces. The articular cartilage was shaved from the femoral and tibial surfaces. Meniscus and articular cartilage fragments were digested separately in a solution of 0.2% collagenase II (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) in serum-free medium. After a 14-18 hr digestion, MCs and ACs were isolated through sequential dilution of the tissue/collagenase solution with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), centrifugation of the mixture, and removal of the supernatant. When the cells were sufficiently separated from the digested tissue, they were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer, counted using a hemocytometer, and frozen at −80°C. The freezing medium consisted of the same medium described above in addition to 20% fetal bovine serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Two weeks after harvest, primary bovine ACs and MCs were thawed and re-suspended in serum-free medium. The cells were then combined in a 50:50 ratio and 20 million cells were seeded into the meniscus-shaped agarose molds described previously. The cell seeding density employed was based on a previous study that identified the cell density range appropriate for self-assembly (Revell et al. 2008). Culture medium was changed every other day for the 4 wk duration of the study. At 4 wks, constructs were removed from the agarose wells and assessed via histological, biochemical, and biomechanical tests.

2.4 Histology

Constructs were cut in half along the major elliptical axis and a cylindrical 2 mm section of neo-tissue was taken from each half-ellipse using a 2 mm biopsy punch. Care was taken to note the orientation of the sample relative to the overall construct. The samples were frozen using HistoPrep (Histo Prep, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and sectioned at 14 μm. Safranin-O / fast green was used to examine GAG distribution and picrosirius red was used for qualitative examination of collagen content. Slides stained with picrosirius red were also viewed under polarized light to examine collagen orientation.

2.5 Biochemistry

Samples were weighed to determine total wet weights and then processed for tensile, compressive, and histological tests. The remainder of the construct was then reweighed, lyophilized for 48 hrs, and then dry weights were measured. Samples were digested in pepsin (10 mg/ml) for 1 day at 4°C followed by elastase (1 mg/ml) for 5 days at 4°C. Biochemical assays performed were dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) (sulfated-GAGs), hydroxyproline (collagen), PicoGreen (cell number), and ELISA (collagen I and collagen II). The DMMB assay for sulfated GAGs was completed using a commercially available Blyscan GAG Assay Kit (Biocolor, Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland). A modified hydroxyproline assay was used to determine total collagen in each construct (Woessner 1961). Each sample was hydrolyzed in 4 M NaOH at 121°C for 1 hr. The samples were then neutralized and placed in buffer. The collagen content was then determined by combining the samples with dimethyl aminobenzaldehyde and chloramine T allowing for a colorimetric comparison. The PicoGreen assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to determine the DNA content of scaffoldless constructs. Collagen II and collagen I amounts were quantified using ELISA protocols described previously (Hoben and Athanasiou 2008). Briefly, for collagen II, Chondrex reagents and protocols were employed (Chondrex, Redmond, WA). For collagen I, a similar protocol was employed with antibodies from US Biological.

2.6 Uniaxial tension

Tensile tests were performed using an Instron 5565 with a 50 N load cell. To ensure testability, samples were taken from the longer axis of the ellipse and carved into a dog-bone shape. The ends were fixed to paper tabs using cyanoacrylate glue. A 0.05 N tare load was applied and the constructs were pulled to failure at a strain rate that was equivalent to 1% of the gauge length. Stress-strain curves were created from the load-displacement curves and the cross-sectional area of the samples; tensile stiffness and ultimate tensile strength were calculated from the linear region of each stress-strain curve. Construct thickness was measured using digital calipers.

2.7 Creep indentation

Disc-shaped constructs, obtained using a 2 mm biopsy punch, were evaluated with an indentation apparatus. The specimens were loaded with a tare mass of 0.4 g (0.004 N), using a 0.5 mm-diameter rigid, flat-ended, porous indenter tip. When tare equilibrium was reached, a step mass of 2.3 g (0.02 N) was applied. Displacement of the sample surface was measured until equilibrium was reached. At that time, the step load was removed, and the displacement recorded until equilibrium was again reached. The aggregate modulus, Poisson’s ratio and permeability of the samples was then determined using the linear biphasic theory.

2.8 Statistical analyses

Biochemical and biomechanical assessments were performed on all constructs (n = 6). A single factor ANOVA was used to analyze the samples, and a Tukey’s post hoc test was used when warranted. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. Univariate regression analysis was also conducted to determine whether the biochemical properties correlated with the biomechanical properties.

3. Results

3.1 Mold-maker roughness

The average roughness value (Ra) was estimated by assuming the surface was entirely composed of semi-circles. Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to estimate the diameter of these semi-circles (~281 μm). Using equation 1, the average roughness (Ra) of the rough mold-maker was calculated to be 44.7 ± 4.0 μm.

3.2 Gross morphology

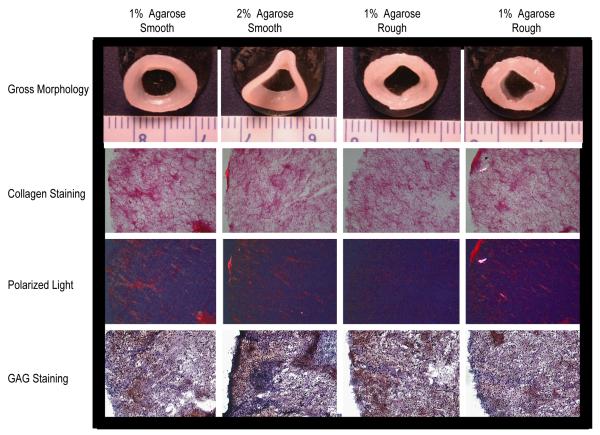

Within 48 hrs of seeding, the cells coalesced into an elliptical shaped construct that grew in size over the 4 wk culture period (Figure 2). At t = 4 wks, the constructs cultured in the smooth agarose wells were extracted with a spatula by maneuvering the construct up the central post. Constructs cultured in the rough agarose wells were more difficult to extract and had pieces of agarose adhered to the construct. The adhered agarose was carefully removed using a spatula prior to histological and biochemical examination. Although translucent cartilage-like tissue was present in all groups, stark differences were observed in the morphology of the constructs in each group. Constructs cultured in the smooth wells exhibited a smooth surface topology while those cultured in rough wells exhibited an uneven topology. In addition, buckling was observed in constructs cultured in 2% agarose wells but was absent in constructs cultured in 1% agarose wells. Each elliptical construct was divided down the major axis to yield two meniscus-shaped-constructs. No significant differences were observed among groups in height (p = 0.70) and thickness (p = 0.38) of the meniscus-shaped constructs (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Gross morphology and histology of constructs cultured for 4 wks. Picrosirius red, polarized light and safranin O / fast-green staining of constructs at 10X magnification.

Table 1.

Gross morphological and biochemical results. Data presented as mean ± SD with significance between groups labeled with different letters (p<0.05).

| Group | Average thickness (mm) |

Average height (mm) |

Wet weight (mg) |

Total GAG (mg) |

Total collagen (mg) |

Collagen I (μg) |

Collagen II (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1% Agarose

Smooth |

3.5 ± 0.1 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

32.7 ± 1.8 b |

1.5 ± 0.3 a |

4.2 ± 0.6 |

22.5 ± 1.7 b |

0.6 ± 0.1 a |

|

2% Agarose

Smooth |

3.7 ± 0.1 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

32.0 ± 2.7 b |

2.0 ± 0.2 ab |

3.8 ± 0.7 |

22.1 ± 4.6 b |

0.6 ± 0.1 a |

|

1% Agarose

Rough |

3.6 ± 0.2 |

1.0 ± 0.0 |

38.8 ± 3.3 a |

1.3 ± 0.3 b |

3.4 ± 0.5 |

45.5 ± 8.9 a |

0.4 ± 0.1 b |

|

2% Agarose

Rough |

3.7 ± 0.2 |

1.0 ± 0.1 |

36.0 ± 1.9 ab |

1.3 ± 0.4 b |

3.4 ± 0.3 |

45.8 ± 7.4 a |

0.4 ± 0.1 b |

| p value | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | 0.05 | < 0.0001 | 0.003 |

3.3 Histology

Uniform collagen and GAG staining was observed in all constructs (Figure 2). Polarized light micrographs showed presence of collagen alignment in the circumferential direction and the alignment was most prominent in constructs cultured in smooth wells with 1% agarose (Figure 2).

3.4 Biochemistry

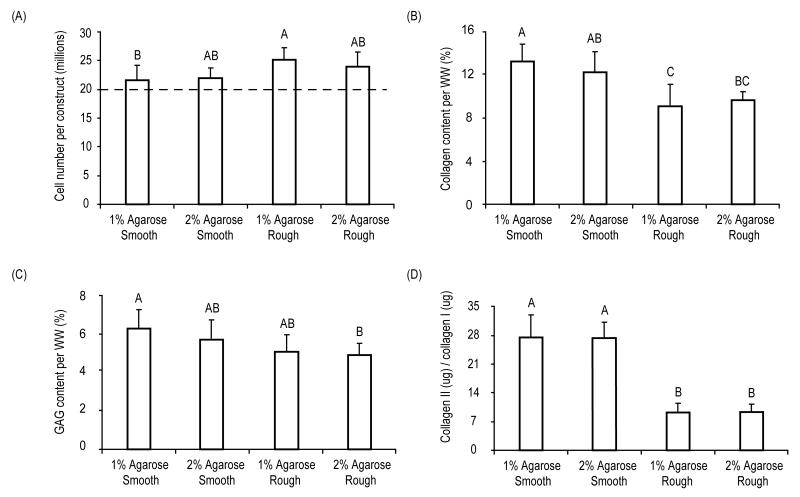

At t = 4 wks, wet weights of the meniscus-shaped constructs were significantly different among groups (p = 0.0004) and ranged from 38.8 ± 3.3 mg (1% agarose rough) to 32.7 ± 1.8 mg (1% agarose smooth) (Table 1). Cell number/construct increased significantly (p = 0.02) from 21.8 ± 2.1 million cells/construct in the 1% smooth agarose group to 25.2 ± 1.9 million cells/construct in the rough 1% agarose group (Figure 3A). Values for the total collagen, GAG, collagen I, and collagen II per construct are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were observed among groups for total collagen per WW (p = 0.0008) (Figure 3B), GAG per WW (p = 0.0003) (Figure 3C) and collagen II to collagen I levels in the constructs (p < 0.0001) (Figure 3D). Specifically, collagen content per WW ranged from 8.9 ± 1.9% in the rough 1% agarose group to 12.9 ± 1.7% in the smooth 1% agarose group, while GAG content per WW ranged from 3.4 ± 0.9% in the rough 1% agarose group to 6.4 ± 0.7% in the smooth 2% agarose group. Collagen II to collagen I ratios in the constructs were highest in cells cultured in smooth wells with values ranging from 9.8 ± 2.3 in the rough 1% agarose group to 27.4 ± 5.3 in the smooth 1% agarose group.

Figure 3.

Biochemical characterization of constructs at t = 4 wks. (A) Cell number per construct. Dashed line indicates original cell seeding density of ~20 million cells per construct. (B) Collagen content normalized to construct wet weight. (C) GAG content normalized to construct wet weight. (D) Collagen II per construct normalized to collagen I per construct. Data presented as mean ± SD with significance among groups labeled with different letters (p < 0.05).

3.5 Biomechanics

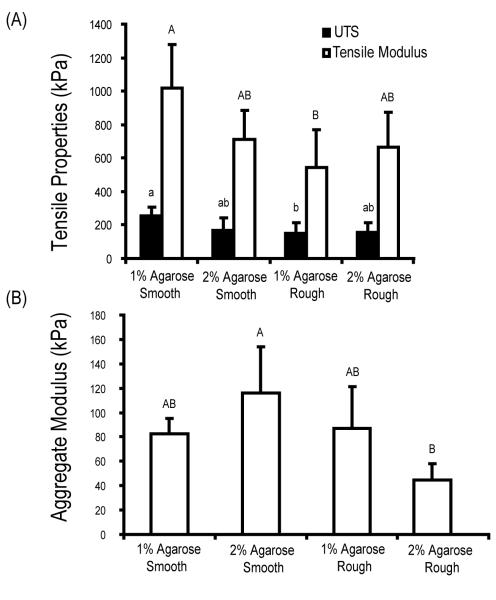

Samples were tested under tension with significant differences observed among groups for the tensile modulus (p = 0.008) and the UTS (p = 0.03) (Figure 4A). Specifically, samples cultured in the smooth 1% agarose wells exhibited the highest tensile modulus (1018 ± 259 kPa) and the highest UTS (252 ± 53 kPa). These values were approximately one and half times (tensile modulus: 534 ± 201 kPa, UTS: 151 ± 66 kPa) those of constructs cultured in the rough 1% agarose wells.

Figure 4.

Biomechanical characterization of constructs at t = 4 wks. (A) Tensile modulus and ultimate strength of constructs. (B) Aggregate modulus determined from creep indentation testing. Data presented as mean ± SD with significance between groups labeled with different letters (p < 0.05).

Meniscus-shaped constructs were evaluated under conditions of creep indentation with significant differences observed among groups for the aggregate modulus (p = 0.002) (Figure 4B). The highest aggregate modulus was found in constructs cultured in the smooth 2% agarose wells (116 ± 38 kPa), approximately two and a half times the aggregate modulus of constructs cultured in rough 2% agarose wells (45 ± 12 kPa). No significant differences were observed among groups for the permeability (p = 0.46) and the Poisson’s ratio (p = 0.91). The values for permeability for the 1% agarose (smooth and rough), and the 2% agarose (smooth and rough) were 4.5 ± 3.2 (× 10−15) m4 / N-s, 7.1 ± 5.1 (× 10−15) m4 / N-s, 4.5 ± 1.6 (× 10−15) m4 / N-s, and 6.7 ± 3.0 (× 10−15) m4 / N-s, respectively. The values for the Poisson’s ratio for the 1% agarose (smooth and rough), and the 2% agarose (smooth and rough) were 0.2 ± 0.1, 0.2 ± 0.1, 0.2 ± 0.1 and 0.2 ± 0.2, respectively.

3.6 Correlation between biochemical and biomechanical data

Compressive and tensile moduli obtained from the biomechanical data were correlated to the total GAG and collagen content in the constructs. Univariate regression analysis showed a significant correlation between tensile modulus and collagen/construct (r2 = 0.44, p = 0.0007) but not for GAG/construct (r2 = 0.0001, p = 0.95). Significant correlations were also observed between aggregate modulus and GAG/construct (r2 = 0.45, p = 0.0004) but not for collagen/construct (r2 = 0.005, p = 0.74).

4. Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that agarose percentage and topography of the mold can significantly influence the final shape of meniscus constructs cultured using a 50:50 ratio of primary bovine MCs and ACs. Specifically, it was found that constructs cultured in 1% agarose wells retained the shape of the original meniscus mold and did not buckle as a result of growth in the radial direction, unlike what was observed with constructs cultured in 2% agarose wells. Interestingly, the biochemical and biomechanical properties of the resulting constructs were also significantly altered. The highest tensile properties and total collagen were observed in the smooth 1% agarose wells, while the highest compressive modulus and total GAG were observed in the smooth 2% agarose wells. Further, collagen II production relative to collagen I production was significantly enhanced in groups cultured in smooth wells.

In this experiment, an elliptical shaped mold was designed that would closely mimic the curved wedge-shaped cross section of the meniscus. The curved shaped profile facilitates the translation of axial compressive forces in the inner regions to circumferential hoop stresses in the outer regions of the meniscus. This provides the meniscus with its shock absorption and load transfer capabilities. In addition, the wedge-shaped profile of the meniscus maintains knee stability by preventing the rounded surface of femur from sliding off the flat surface of the tibia. In a previous experiment examining various co-culture ratios of ACs and MCs seeded in circular ring-shaped molds, we observed that the 50:50 co-culture ratio resulted in a construct approaching the geometry of the native meniscus (Aufderheide and Athanasiou 2007). To more accurately depict the overall geometry of the meniscus, the mold design was optimized from a ring to an ellipse and the bottom of the mold was fashioned with a changing concave slope to mimic the variation in cross-sectional area of the meniscus. These modifications resulted in constructs more closely mimicking native tissue, especially those cultured in smooth 1% agarose wells.

Two different agarose percentages (1% and 2%) were examined in this experiment to determine their effect on construct geometry during the culturing phase. In previous work, meniscus constructs grown in a ring-shaped mold expanded radially and buckled as they reached the confining walls of 2% agarose wells. Compared to 1% agarose wells, the 2% agarose wells exhibit lower compliance and exert greater inward forces onto the constructs as they expand. Mechanical properties of agarose gels have been shown to be concentration dependent with an equilibrium aggregate modulus of 5 kPa for 1% w/v agarose gels and approximately 20 kPa for 2% w/v agarose gels (Awad et al. 2002). We hypothesized that buckling may be reduced by utilizing a lower percentage agarose well with increased compliance. This was confirmed by our results where constructs cultured in 1% agarose wells formed meniscus-shaped constructs with no buckling, while constructs cultured in 2% agarose wells buckled.

In addition to agarose percentage, the effect of well topography was also examined on the final geometrical shape of the meniscus construct. Studies have shown that cells are sensitive to the surface texture of the material and can alter their attachment, phenotype and matrix deposition patterns on different topographies (Bowers et al. 1992; Martin et al. 1995; Schwartz et al. 1996). For instance, microgrooves on a surface have been shown to alter morphology of osteoblasts and influence matrix deposition (Matsuzaka et al. 2000). In this experiment, constructs in smooth agarose wells were easily removed using a spatula at 4 wks. Interestingly, constructs cultured on rough surfaces exhibited resistance upon removal and appeared attached to the bottom of the agarose wells. Surface roughness may have provided the means for interdigitation of the construct into the biomaterial. We hypothesize that portions of the developing matrix were anchored into the microgrooves of the molds. As the construct expanded to the well edge, buckling was prevented due to construct anchorage to the well bottom. However, reactionary tensile forces on the constructs, as a result of non-homogeneous interdigitation with agarose, led to overall uneven construct topology and impeded construct extraction from the well. Thus, although the original hypothesis that rough surfaces would eliminate buckling due to increased frictional contact was proven, the geometry of the final construct did not mimic the meniscus due to its high degree of unevenness.

An interesting result of this study was that cell number was significantly higher in constructs cultured on rough surfaces. One potential reason for this may be dedifferentiation and subsequent proliferation of primary ACs and MCs as a result of tensile forces exerted due to interdigitation of the construct with the agarose mold. The ECM is capable of transducing external mechanical stimuli into changes in cell function through mechanotransduction. At the cellular level, mechanical forces can stretch protein-cell surface integrin binding sites, deform gap junctions containing calcium sensitive stretch receptors, alter ion channel permeability, and lead to activation of anabolic or catabolic factors (Leipzig and Athanasiou 2007; Silver and Siperko 2003). These cellular changes can trigger intracellular pathways that can influence cell division as well as the regulation of genes that synthesize ECM molecules (Silver and Siperko 2003). In this experiment, tensile forces appeared to dedifferentiate MCs and ACs cultured in rough wells towards a fibroblastic lineage, a phenomenon that has been observed previously with mesenchymal stem cells (Altman et al. 2002). Increases were observed in collagen I relative to collagen II production and decreases were observed in GAG production in rough wells when compared to ECM produced in smooth wells. It has been previously shown with TMJ disc fibrochondrocytes that dedifferentiation of cells can also lead to enhanced cell division and proliferation (Allen and Athanasiou 2007). Thus, cell dedifferentiation due to the external mechanical stimulus likely contributed to increased cell number and decreased cartilaginous matrix production in constructs cultured on rough surfaces.

This experiment utilized a co-culture of primary bovine MCs and ACs. Through this approach, large quantities of collagen II and GAG were obtained, both of which are important ECM molecules present in the inner regions of the rabbit meniscus. Primary cells were chosen since passaged MCs and ACs dedifferentiate in monolayer and express high levels of collagen I, and low levels of collagen II and aggrecan (Darling and Athanasiou 2003; Gunja and Athanasiou 2007). Bovine cells were judiciously chosen to recreate the rabbit meniscus since they are an easily available cell source that can be harnessed to develop meniscus tissue engineering technologies. In addition, bovine cells may also be considered as a potential xenogenic cell source for leporine meniscus tissue engineering. For this approach to be successful in vivo, a battery of tests will need to be conducted in vitro and in vivo to ensure the cells do not elicit a humoral or cell mediated immune response. A number of in vivo studies have examined the potential of xenogenic implantation of cartilage or chondrocytes and have noted a lack of immune response (Ramallal et al. 2004; van Susante et al. 1999; Yan and Yu 2007). Furthermore, chondrocytes have been shown inability to induce T-cell proliferation in an in vitro model (Jobanputra et al. 1992). Though in future animal studies a humoral response would likely not be of concern due to expression of alpha-galactosyl epitopes in both leporine and bovine species (Galili 2005), care should be taken to address this ECM epitope for clinical translation.

To enhance the clinical translatability of our approach, as well as to modulate the phenotype of cells during culture, this experiment utilized a serum-free medium to grow meniscus-shaped constructs. Previous studies have shown that serum-free medium containing additives such as ITS+ and dexamethasone can significantly enhance GAG production in ACs (Adkisson et al. 2001; Chua et al. 2005). We have also obtained similar results in a previous study comparing serum-containing and serum-free medium (Hoben and Athanasiou 2008). Co-cultures of MCs and ACs (50:50), grown in cylindrical molds using a similar scaffoldless approach, were found to contain higher levels of GAG in constructs in serum-free medium when compared to those cultured in serum-containing medium. In addition, total collagen was increased and the collagen I to collagen II ratio was decreased when comparing serum-free culture to serum-containing culture. This showed that the matrix was more cartilaginous in nature when cultured in serum-free conditions. Our results utilizing the elliptical mold design were even more dramatic, with greater amounts of total collagen II produced than collagen I. Specifically, collagen II levels surpassed collagen I levels by at least ten times in constructs cultured in rough wells and up to 27 times in constructs cultured in smooth wells. This was an exciting result, especially since the inner region rabbit meniscus contains a high amount of collagen II. In future work, AC to MC ratios can be modified to attain the correct levels of each type of collagen in the construct.

While recapitulating the geometric shape of the meniscus is an important component of a meniscus tissue engineering strategy, the functional properties of the engineered construct are also an effective assessment tool. Examination of the structure-function relationships of the constructs showed that increased GAG levels resulted in increased compressive stiffness of the constructs, while increased collagen content resulted in increased tensile stiffness of the construct. It was exciting to note that the self-assembled menisci exhibited properties on par with native meniscus values. For example, GAG levels per wet weight (~5 to 6%) were similar to those of the native rabbit meniscus (~3-4%). Collagen levels per wet weight (8-13%) were, in general, lower than native values (~23%) (Sweigart and Athanasiou 2001). Compressive stiffness of constructs cultured in 2% agarose smooth wells (~120 kPa) mimicked that of the outer regions of the rabbit meniscus (~120 kPa), although the compressive properties of the inner meniscus are four times higher (~510 kPa). In terms of tensile properties, the highest tensile stiffness (~1 MPa) and UTS (~0.25 MPa) were observed in the 1% agarose smooth wells. These results were corroborated by polarized light micrographs showing most prominent collagen alignment in this group. In spite of this, the tensile values obtained were two orders of magnitude below those of native tissue (Sweigart and Athanasiou 2005). Thus, future work will need to investigate strategies to enhance the tensile properties of the constructs without comprising their compressive properties.

It is difficult to determine the adequacy of the biomechanical properties of engineered cartilage aimed at tissue replacement due to the lack of studies correlating mechanical integrity to successful in vivo application. The major deficiency of the meniscus constructs formed in this study, and other scaffoldless cartilage engineering attempts, are the tensile properties. However, with proper stimulation these properties may be enhanced to approach native values. For example, by applying a deadweight to the construct within the well, the tensile modulus can be increased by 40% (Elder and Athanasiou 2008a). Also, recent reports have shown that C-ABC application has been able to increase the tensile modulus by 70% (Natoli et al. 2009). TGFβ-1, hydrostatic pressure, and the combination have all shown success at enhancing tensile properties. TGFβ-1 alone and hydrostatic pressure alone increases the tensile modulus by 100%. The combination of these two stimuli resulted in a construct tensile moduli 3 times greater than culture controls (Elder and Athanasiou 2008b). Therefore, while the properties reported in this study may not be ideal for implantation, future work aimed at selecting appropriate stimuli for meniscus constructs should be able to greatly enhance the biomechanical properties. However, it should be emphasized that it is still unclear as to whether our tissue engineering objective should be to achieve construct properties identical to those of the native tissue. It may be that upon implantation constructs with inferior properties may rapidly integrate with adjacent tissue and achieve native tissue values. More in vivo studies need to be performed to investigate this issue.

In conclusion, a smooth mold made of 1% agarose was able to create geometrically-mimetic meniscus constructs for meniscus tissue engineering using a scaffoldless approach. Rough wells inhibited construct buckling but resulted in uneven shaped constructs. Stark changes were observed in ECM components among groups, with smooth wells enhancing cartilaginous markers such as GAG and collagen II and rough wells enhancing the fibroblastic marker collagen I. Overall, this work presents an effective strategy for knee meniscus tissue engineering using a self-assembly, scaffoldless process to create constructs approaching the geometrical, biochemical, and biomechanical properties of the native meniscus.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH R01 AR 47839

References

- Adkisson HD, Gillis MP, Davis EC, Maloney W, Hruska KA. In vitro generation of scaffold independent neocartilage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(391 Suppl):S280–94. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KD, Athanasiou KA. Effect of passage and topography on gene expression of temporomandibular joint disc cells. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(1):101–10. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman GH, Horan RL, Martin I, Farhadi J, Stark PR, Volloch V, Richmond JC, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Cell differentiation by mechanical stress. Faseb J. 2002;16(2):270–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0656fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide AC, Athanasiou KA. Assessment of a bovine co-culture, scaffold-free method for growing meniscus-shaped constructs. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(9):2195–205. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad HA, Erickson GR, Guilak F. Biomaterials for cartilage tissue engineering. In: Lewandrowski KU, Wise DL, Trantolo DJ, Gresser JD, Yaszemski MJ, Altobelli DE, Wise DL, Trantolo DJ, Gresser JD, Yaszemski MJ, editors. Tissue engineering and biodegradable equivalents: scientific and clinical applications. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 267–299. others. [Google Scholar]

- Ballyns JJ, Gleghorn JP, Niebrzydowski V, Rawlinson JJ, Potter HG, Maher SA, Wright TM, Bonassar LJ. Image-guided tissue engineering of anatomically shaped implants via MRI and micro-CT using injection molding. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(7):1195–202. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers KT, Keller JC, Randolph BA, Wick DG, Michaels CM. Optimization of surface micromorphology for enhanced osteoblast responses in vitro. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;7(3):302–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casscells SW. The torn or degenerated meniscus and its relationship to degeneration of the weight-bearing areas of the femur and tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;132:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiari C, Koller U, Dorotka R, Eder C, Plasenzotti R, Lang S, Ambrosio L, Tognana E, Kon E, Salter D. A tissue engineering approach to meniscus regeneration in a sheep model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(10):1056–65. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.007. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua KH, Aminuddin BS, Fuzina NH, Ruszymah BH. Insulin-transferrin-selenium prevent human chondrocyte dedifferentiation and promote the formation of high quality tissue engineered human hyaline cartilage. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;9:58–67. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v009a08. discussion 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DL, Malone E, Lipson H, Bonassar LJ. Direct freeform fabrication of seeded hydrogels in arbitrary geometries. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(5):1325–35. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Nye CE, Schaefer WW, Woodstein IJ. The degenerative effects of partial and total resection of the medial meniscus in dogs’ knees. Clin Orthop. 1975;109:178–83. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197506000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling EM, Athanasiou KA. Articular cartilage bioreactors and bioprocesses. Tissue Eng. 2003;9(1):9–26. doi: 10.1089/107632703762687492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder BD, Athanasiou KA. Effects of confinement on the mechanical properties of self-assembled articular cartilage constructs in the direction orthogonal to the confinement surface. J Orthop Res. 2008a;26(2):238–46. doi: 10.1002/jor.20480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder BD, Athanasiou KA. Synergistic and additive effects of hydrostatic pressure and growth factors on tissue formation. PLoS ONE. 2008b;3(6):e2341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank T. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br) 1948;30:664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop. 1990;252:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili U. The alpha-gal epitope and the anti-Gal antibody in xenotransplantation and in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83(6):674–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunja NJ, Athanasiou KA. Passage and reversal effects on gene expression of bovine meniscal fibrochondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R93. doi: 10.1186/ar2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoben GM, Athanasiou KA. Creating a spectrum of fibrocartilages through different cell sources and biochemical stimuli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;100(3):587–98. doi: 10.1002/bit.21768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. A self-assembling process in articular cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(4):969–79. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobanputra P, Corrigall V, Kingsley G, Panayi G. Cellular responses to human chondrocytes: absence of allogeneic responses in the presence of HLA-DR and ICAM-1. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90(2):336–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RS, Keene GC, Learmonth DJ, Bickerstaff D, Nawana NS, Costi JJ, Pearcy MJ. Direct measurement of hoop strains in the intact and torn human medial meniscus. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1996;11(5):295–300. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(96)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SW, Son SM, Lee JS, Lee ES, Lee KY, Park SG, Park JH, Kim BS. Regeneration of whole meniscus using meniscal cells and polymer scaffolds in a rabbit total meniscectomy model. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78(3):659–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa H, Fukubayashi T, Nakajima H. Load-bearing mode of the knee joint: physical behavior of the knee joint with or without menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;149:283–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipzig ND, Athanasiou K. Static compression of single chondrocytes catabolically modifies single cell gene expression. Biophys J. 2007 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JY, Schwartz Z, Hummert TW, Schraub DM, Simpson J, Lankford J, Jr., Dean DD, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. Effect of titanium surface roughness on proliferation, differentiation, and protein synthesis of human osteoblast-like cells (MG63) J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29(3):389–401. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinek V, Ueblacker P, Braun K, Nitschke S, Mannhardt R, Specht K, Gansbacher B, Imhoff AB. Second generation of meniscus transplantation: in-vivo study with tissue engineered meniscus replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126(4):228–34. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka K, Walboomers F, de Ruijter A, Jansen JA. Effect of microgrooved poly-l-lactic (PLA) surfaces on proliferation, cytoskeletal organization, and mineralized matrix formation of rat bone marrow cells. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11(4):325–33. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011004325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt CA, Miller RR, Spindler KP. The cells and cell matrix interactions of the meniscus. In: Mow VC, Arnoczky SP, Jackson DW, editors. Knee Meniscus: Basic and Clinical Foundations. Raven Press; New York: 1992. pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meakin JR, Shrive NG, Frank CB, Hart DA. Finite element analysis of the meniscus: the influence of geometry and material properties on its behaviour. Knee. 2003;10(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(02)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli RM, Responte DJ, Lu BY, Athanasiou KA. Effects of multiple chondroitinase ABC applications on tissue engineered articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jor.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin EL, de Lamotte F, Maquet P. Role of the menisci in the distribution of stress in the knee. Clin Orthop. 1984;185:290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramallal M, Maneiro E, Lopez E, Fuentes-Boquete I, Lopez-Armada MJ, Fernandez-Sueiro JL, Galdo F, De Toro FJ, Blanco FJ. Xeno-implantation of pig chondrocytes into rabbit to treat localized articular cartilage defects: an animal model. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(3):337–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell CM, Reynolds CE, Athanasiou KA. Effects of initial cell seeding in self assembly of articular cartilage. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(9):1441–8. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Z, Martin JY, Dean DD, Simpson J, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. Effect of titanium surface roughness on chondrocyte proliferation, matrix production, and differentiation depends on the state of cell maturation. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;30(2):145–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199602)30:2<145::AID-JBM3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver FH, Siperko LM. Mechanosensing and mechanochemical transduction: how is mechanical energy sensed and converted into chemical energy in an extracellular matrix? Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2003;31(4):255–331. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v31.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone KR. Current and future directions for meniscus repair and replacement. Clin Orthop. 1999;(367 Suppl):S273–80. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199910001-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweigart MA, Athanasiou KA. Toward tissue engineering of the knee meniscus. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(2):111–29. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweigart MA, Athanasiou KA. Tensile and compressive properties of the medial rabbit meniscus. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 2005;219(5):337–47. doi: 10.1243/095441105X34329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Susante JL, Buma P, Schuman L, Homminga GN, van den Berg WB, Veth RP. Resurfacing potential of heterologous chondrocytes suspended in fibrin glue in large full-thickness defects of femoral articular cartilage: an experimental study in the goat. Biomaterials. 1999;20(13):1167–75. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner JF. The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;93:440–447. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Yu C. Repair of full-thickness cartilage defects with cells of different origin in a rabbit model. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(2):178–87. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]