Abstract

Clinical and experimental data suggest dysregulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-mediated glutamatergic pathways in schizophrenia. The interaction between NMDAR-mediated abnormalities and the response to novel environment has not been studied. Mice expressing 5 to 10% of normal N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit 1 (NR1) subunits [NR1neo(−/−)] were compared with wild-type littermates for positive deflection at 20 ms (P20) and negative deflection at 40 ms (N40) auditory event-related potentials (ERPs). Groups were tested for habituation within and across five testing sessions, with novel environment tested during a sixth session. Subsequently, we examined the effects of a GABAA positive allosteric modulator (chlordiazepoxide) and a GABAB receptor agonist (baclofen) as potential interventions to normalize aberrant responses. There was a reduction in P20, but not N40 amplitude within each habituation day. Although there was no amplitude or gating change across habituation days, there was a reduction in P20 and N40 amplitude and gating in the novel environment. There was no difference between genotypes for N40. Only NR1neo(−/−) mice had reduced P20 in the novel environment. Chlordiazepoxide increased N40 amplitude in wild-type mice, whereas baclofen increased P20 amplitude in NR1neo(−/−) mice. As noted in previous publications, the pattern of ERPs in NR1neo(−/−) mice does not recapitulate abnormalities in schizophrenia. In addition, reduced NR1 expression does not influence N40 habituation but does affect P20 in a novel environment. Thus, the pattern of P50 (positive deflection at 50 ms) but not N100 (negative deflection at 100 ms) in human studies may relate to subjects’ reactions to unfamiliar environments. In addition, NR1 reduction decreased GABAA receptor-mediated effects on ERPs while causing increased GABAB receptor-mediated effects. Future studies will examine changes in GABA receptor subunits after reductions in NR1 expression.

Clinical and experimental evidence suggests dysregulation of glutamatergic pathways and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) function may play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin, 1991). NMDAR antagonists such as 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl) piperidine and ketamine provoke a syndrome in normal individuals that resembles symptoms of schizophrenia (Javitt and Zukin, 1991) and exacerbate symptoms in patients with schizophrenia (Lahti et al., 2001).

Genetically altered mouse strains have been a valuable tool for the study of diseases associated with impaired glutamatergic neurotransmission. We used a previously described mouse mutant to investigate the effects of constitutively reduced NMDAR signaling (Mohn et al., 1999; Duncan et al., 2004; Bickel et al., 2008). NR1neo(−/−) mice express 5 to 10% of the normal level of the NR1 of the NMDAR and have been shown to exhibit behaviors relevant to schizophrenia, including hyperlocomotion, stereotypy, and sensorimotor gating deficits (Bickel et al., 2008). Previous data indicate that the NR1neo(−/−) mice display electrophysiological abnormalities such as increased amplitude and changes in recovery cycle as measured with event-related potentials (ERPs) (Bickel et al., 2008; Halene et al., 2009).

Although genomic factors play a role in expression of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, its etiology is multifactorial with environmental factors such as stress being important albeit more elusive regarding their impact (Kendler et al., 1995). Stress is known to cause exacerbation and recurrence of symptoms after a period of remission (Norman and Malla, 1993; Piazza and Le Moal, 1998; Jansen et al., 2000). Reduced NMDA receptor function may increase vulnerability to stress-activated alterations in neurotransmission, with resulting exacerbation of symptoms. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of habituation to reverse the ERP abnormalities in NR1neo(−/−) mice. We then introduced a novel testing environment as a stressor to determine whether the effect of habituation could be reversed as a model for stress-mediated relapse of psychosis.

In addition to habituation, we proposed that drugs that stimulate GABAergic neurotransmission would selectively normalize ERPs in NR1neo(−/−) mice. This hypothesis is based on the observation that NMDA receptors are present on GABAergic interneurons and that glutamate acts on these receptors to activate inhibitory projections of these cells. Therefore, diminished NR1 expression could reduce the inhibitory action of GABAergic interneurons. This NR1-mediated deficit could then cause a loss of inhibitory control over multiple projections (Farber, 2003). Impaired NMDA receptor function in NR1neo(−/−) mice could therefore result in reduced activation of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons, yielding increased amplitude of their ERPs. We propose that if GABAergic function is stimulated with an agonist, then inhibitory control could be restored, reducing ERP amplitude. Preliminary data also indicate that NR1-deficient mice have a reduction of parvalbumin-positive interneurons (J. Sisti, T.B. Halene, C.R. Majewski-Tiedeken, G. Jonak, E.P. Christian, and S.J. Siegel, unpublished data). Therefore, we hypothesized that adding a GABA agonist would increase inhibitory tone and normalize the relatively high-amplitude ERPs.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The NR1neo(−/−) mice (Mohn et al., 1999) were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Beverly Koller (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC) and a breeding colony was established at AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP (Wilmington, DE). Their breeding involves three populations of mice: NR1neo+/− heterozygotes maintained on C57BL/6 background (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), NR1neo+/− heterozygotes maintained on 129/SvEv background (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY), and an intercross between female C57BL/6 NR1neo+/− and male 129/SvEv NR1neo+/−. The progeny from the intercross are genetically identical F1 hybrids with the exception at NR1 locus: 50% NR1neo+/−, 25% NR1neo(−/−), and 25% wild type (WT). A polymerase chain reaction protocol provided by B. Koller was used for genotyping these mice: NR1 (+) forward primer (intron 20), 5′-TGA GGG GAA GCT CTT CCT GT-3′; NR1 (−) forward primer (neo), 5′-GCT TCC TCG TGC TTT ACG GTA T-3′; and NR1 common reverse primer (intron 20), 5′-AAG CGA TTA GAC AAC TAA GGG T-3′. For experiments described here, only male mice were used. Two cohorts of 16 NR1neo(−/−) and 16 wild-type littermates were generated by AstraZeneca Neuroscience (Wilmington, DE) and arrived at the University of Pennsylvania when 8 weeks old. A third cohort of 8 NR1neo(−/−) and eight wild-type littermates was later generated and housed at Astra Zeneca Neuroscience for the repletion of locomotor activity testing. Animals were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 PM) in a temperature-controlled facility with food and water available ad libitum. Mice were housed four to five per cage and acclimated to the housing facility for 1 week before surgery. After electrode placement, each mouse was housed individually. Surgeries and behavioral and electrophysiological testing occurred between 9 and 19 weeks of age. All tests were performed during the light phase between 2:00 PM and 5:00 PM. Gonadectomized male A/J mice (8–30 weeks old) used as stimulus mice for the social-choice paradigm were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Adequate measures were taken to minimize pain or discomfort. All protocols were approved by the AstraZeneca and University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use committees and were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) guidelines.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction.

RNAs were extracted from cerebral cortices of both wild-type and NR1 hypomorph mice using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and further purified using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Total RNAs (∼4 μg) were reverse-transcribed using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and resultant cDNA templates were used for qPCR reactions using primers for NR1 (specific for exon 18 of the mouse gene) and β-actin purchased from Superarray Bioscience Corporation (Frederick, MD). mRNAs were quantified in duplicates using 50 ng of total RNA, 400 nM of both forward and reverse primers, and 12.5 μl of 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and performed with a Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The data analyses were carried out using Prism software, version 1.2.3 (Applied Biosystems). NR1 expression levels were normalized to β-actin and between-group differences were presented as -fold change defined as 2−Δ(CT compared with expression levels in wild-type mice, with 95% confidence interval. Statistical analyses were performed by one single t test (assuming the mean column value for wild type is 1.00) and Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Western Blotting.

Cortices of five mice from each group, the wild type [NR1neo(+/+)] group and transgenic [NR1neo(−/−)] group, were surgically removed and homogenized in homogenization buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM 2-glycerophosphate supplemented with 5 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 0.05% 2-mercaptoethanol. The homogenates were centrifuged at 800g to remove nuclear debris, and the supernatants were solubilized with 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5% digitonin for an hour at 4°C. The extracts were cleared at 16,000g, and protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined by Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976). Then, 25 μg of protein extracts was loaded on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis precast gels (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) and transferred on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was blocked in 3% nonfat milk and probed with anti-NMDAR1 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-β-actin (mouse monoclonal, 1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by 1:2000 anti-goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and 1:5000 anti-mouse (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK) secondary antibodies. Blots were developed with chemiluminescence reagent ECL (GE Healthcare).

Surgery.

Animals underwent stereotaxic implantation of tripolar electrode assemblies (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) for nonanesthetized recording of auditory ERPs. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. Three stainless steel electrodes, mounted in a single pedestal, were aligned along the sagittal axis of the skull at 1-mm intervals with precut lengths of 3 mm (positive) and 1 mm (ground and negative). Positive electrodes were placed in the right cornu ammonis 3 hippocampal region at 1.8 mm posterior, 2.65 mm right lateral, and 2.75 mm deep relative to bregma (junction of the sagittal and coronal sutures used as surgical point of reference). Negative electrodes were placed adjacent to positive and ground electrodes on the ipsilateral cortex at 0.2 mm anterior, 2.75 mm lateral, and 0.75 mm deep relative to bregma. Ground electrodes were located between positive and negative electrodes on the ipsilateral cortex at 0.8 mm posterior, 2.75 mm lateral, and 0.75 mm deep relative to bregma. The electrode pedestal was secured to the skull with ethyl cyanoacrylate (Loctite; Henkel, Düsseldorf, Germany) and dental cement (Ortho Jet; Lang Dental, Wheeling IL).

Recording of Auditory ERPs.

Recording of brain activity for auditory ERPs was performed 2 weeks after electrode implantation. For the habituation study, mice were tested for five consecutive habituation days in a familiar environment, followed by one stress day in a novel environment. Each animal was placed in its home cage with bedding (31 × 19 × 16 cm) during habituation days and the pharmacological assessment and in an unfamiliar cage without bedding (45 × 23 × 22 cm) on the stress day. Mice were handled by the same researcher during habituation days. Other researchers who had no previous contact with these mice performed the handling on the stress day. For both studies, cages were placed in a sound-attenuated recording chamber inside a Faraday electrical isolation cage. Background white noise was 64 dB. Electrode pedestals were connected to a 30-cm tripolar electrode cable that exited the chamber to connect to a high-impedance differential AC amplifier (A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA). Auditory ERPs were recorded as described previously (Connolly et al., 2004; Maxwell et al., 2006b). Stimuli were generated by Micro 1401 hardware with Spike 2, version 6 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) and were delivered through speakers attached to the cage top. The responses to first and second stimulus of a pair are referred to as S1 and S2, respectively. The sequencer file for habituation and stress condition consisted of a series of 1250 paired stimuli presented 500 ms apart, with a 9-s interstimulus interval (800 Hz; 85-dB sound pressure; 10-ms single stimulus duration). A series of 100 paired stimuli (same stimulus characteristics as described above) were presented for pharmacological assessments due to the relatively short serum half-life for most agents in mouse. Recording sessions for every group of mice were preceded by a 15-min acclimation phase and subsequent to stimulus presentation.

Treatment Groups.

All drugs were injected intraperitoneally 5 min before ERP recording. Chlordiazepoxide (Sigma-Aldrich), a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors, was injected at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Baclofen (Sigma-Aldrich), a GABAB agonist, was injected at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Drugs were diluted in 0.9% saline solution. Mice were first tested with no pharmacologic intervention, followed by testing after injection of 0.9% saline solution, and concluded with testing after drug administration. The doses tested were selected based on previous studies using these compounds in mice (Rodgers et al., 2002; Gasior et al., 2004).

Analysis.

Twelve wild-type and 13 NR1neo(−/−) mice were analyzed for the effect of habituation and stress on their ERP recordings. A subset of seven NR1neo(−/−) and eight wild-type mice were analyzed for the effect of chlordiazepoxide on ERPs. Another subset of eight NR1neo(−/−) and eight wild-type mice were analyzed for the effect of baclofen.

The 1250 paired stimuli were broken up into groups of 250 for each of the habituation and stress days. Each of these groups was called an epoch and was given a respective number 1 through 5, with E1 corresponding to the first epoch and E5 corresponding to the last epoch. To evaluate intraday habituation, only the first (E1) and last (E5) epoch were compared.

The amplitude of the P20 (most positive deflection between 10 and 30 ms) and N40 (most negative deflection between 25 and 60 ms) were determined. A repeated measures analysis of variance was used to determine interactions of genotype, stimulus, day, and epoch on habituation and stress days, and interactions of genotype, stimulus, and drug for the pharmacological assessment. Significant interactions were followed up with Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc analyses. The α levels were set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

qPCR and Western Blotting

NR1 expression levels were assessed using qPCR and Western blot. In five pairs of NR1 hypomorphs and their controls, the -fold change for NR1 transcripts in hypomorphs was 0.39 (95% confidence interval, 0.33–0.46) compared with that in wild type as 1.00 (95% confidence interval, 0.86–1.17) (Fig. 1). When NR1 protein levels were measured by Western blot, the expression of 110-kDa NR1 was found to be further decreased in the hypomorphs to 10 ± 0.02% of controls.

Fig. 1.

mRNA and protein expression of NR1 in NR1neo(−/−) and wild-type mice. NR1 expression levels were assessed using qPCR and Western blot. A, qPCR was performed in five pairs of NR1neo(−/−) and wild-type controls, the -fold change for NR1 transcripts in NR1neo(−/−) was 0.39 (95% confidence interval, 0.33–0.46) compared with that in wild type as 1.00 (95% confidence interval, 0.86–1.17). B, Western blot: 25 μg of protein extracts from the cortex of three wild-type and three NR1neo(−/−) mice was separated on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted for NR1 along with β-actin as loading controls. The expression of 110-kDa NR1 was found to be further decreased in the NR1neo(−/−) mice to 10 ± 0.02% of controls. ∗, p < 0.0001.

Mohn et al. (1999) have reported previously a more pronounced decrease in NR1 mRNAs in hypomorphs (8.1 ± 1.3% of controls) than observed in our study. This discrepancy can be partly attributed to different methods of NR1 mRNA quantification. The previous study used Northern blot analyses with cDNA probes specific for exon 22, whereas the present study used qPCR with the probes specific for exon 18. The NR1 hypomorphs harbor an insertional mutation within intron 21, which may affect the transcription of exon 22 more severely than exon 18. Of note, there are at least two splice variants, NR1X10 and NR1X00, that may not be affected by mutations in intron 21 (Zukin and Bennett, 1995). Therefore, some of the transcripts detected in the present study may represent splice variants that are less affected by the mutations in intron 21. Another source of differences could result from brain regions examined in each study. The previous study used the whole brain tissues, whereas our study used cortices, which were found to have more abundant expression of the two splice variants NR1X10 and NR1X00 (Zukin and Bennett, 1995).

Event-Related Potentials

The large number of complex interactions precluded our ability to fully describe all effects in detail. Therefore, the most meaningful aspects are highlighted in the text. A complete list of all statistical results is noted in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

P20 habituation study statistical values

| P20 | F | df | p | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 28.82 | 1, 23 | <0.001 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Epoch | 10.25 | 1, 23 | 0.004 | First > last |

| Stimulus | 96.27 | 1, 23 | <0.001 | S1 > S2 |

| Day | 0.610 | 5, 115 | 0.693 | Not significant |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 12.315 | 1, 23 | 0.002 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus | 9.651 | 1, 23 | 0.005 | E1 S1 > E2 S1 |

| No S2 difference between epochs | ||||

| Epoch/day | 2.961 | 5, 115 | 0.015 | E1 > E2 during habituation days |

| E1 = E2 on stress day | ||||

| Epoch/genotype | 0.002 | 1, 23 | 0.962 | Not significant |

| Day/genotype | 0.738 | 5, 115 | 0.596 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/day | 0.745 | 5, 115 | 0.592 | Not significant |

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Epoch/day/genotype | 2.877 | 5, 115 | 0.017 | NR1neo(−/−): E1 habit > E1 stress |

| Wild type: no effect of stress day | ||||

| No effect of stress day on E2 | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus/day | 2.673 | 5,115 | 0.025 | Habit E1 S1> stress E1 S1 |

| Epoch/stimulus/genotype | 0.072 | 1, 23 | 0.791 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/day/genotype | 0.205 | 5, 115 | 0.960 | Not significant |

| Four-way interaction | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus/day/genotype | 0.917 | 5, 115 | 0.472 | Not significant |

TABLE 2.

N40 habituation study statistical values

| N40 | F | df | p | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 38.707 | 1, 23 | <0.001 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Epoch | 1.507 | 1, 23 | 0.232 | Not significant |

| Stimulus | 423.50 | 1, 23 | <0.001 | S1 > S2 |

| Day | 4.724 | 5, 115 | 0.0006 | Habituation day > stress day |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 67.438 | 1, 23 | <0.001 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus | 5.737 | 1, 23 | 0.025 | E2 S1 > E1 S1 |

| No S2 difference between epochs | ||||

| Epoch/day | 7.823 | 5, 115 | <0.001 | Stress day E1 > habituation day E1 |

| No effect on E2 | ||||

| Epoch/genotype | 0.693 | 1, 23 | 0.414 | Not significant |

| Day/genotype | 0.452 | 5, 115 | 0.811 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/day | 4.660 | 5, 115 | 0.0006 | Habituation days S1 > stress day S1 |

| S2 no effect of day | ||||

| Habituation days S1 > S2 | ||||

| Habituation S1 > stress day S1 > S2 | ||||

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Epoch/day/genotype | 1.187 | 5, 115 | 0.320 | Not significant |

| Epoch/stimulus/day | 4.795 | 5, 115 | 0.0005 | Habituation: S1 E1 > S2 E1 |

| Stress: S1 E1 = S2 E1 | ||||

| Habituation: S1 E1 > stress: S1 E1 | ||||

| Habituation: S2 E1 = stress: S2 E1 | ||||

| No effect on E2 | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus/genotype | 0.016 | 1, 23 | 0.900 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/day/genotype | 1.255 | 5, 115 | 0.288 | Not significant |

| Four-way interaction | ||||

| Epoch/stimulus/day/genotype | 0.467 | 5, 115 | 0.800 | Not significant |

Habituation Study

P20.

There were significant main effects of genotype, epoch, and stimulus but no main effect of day. The NR1neo(−/−) mice had larger ERPs than the wild types, consistent with previous studies (Bickel et al., 2008; Halene et al., 2009). E1 response was larger than E5 response across all habituation days. S1 was also larger than the S2, demonstrating gating. However, there was no effect of day, indicating that habituation of ERPs was not maintained between testing sessions.

There were significant interactions between stimulus and genotype, epoch and stimulus, and epoch and day, but no significant interactions between other pairs of variables (Table 1). S1 of the NR1neo(−/−) mice was larger than S1 of the wild-type mice. However, S2 amplitudes were similar for both genotypes. E1 response was larger than E5 response for S1, but there was no difference in epoch for S2. Throughout the habituation days, E1 response was larger than E5. However, on the stress day E1 response decreased to the level of E5. S1 remained larger than the S2 throughout all days, suggesting that gating was not disrupted by habituation or stress.

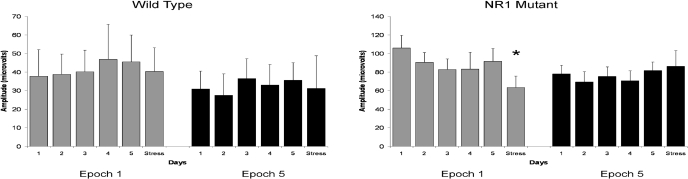

There were significant three-way interactions among epoch, stimulus, and day (Fig. 2) and epoch, day, and genotype (Fig. 3). However, there were no significant three-way interactions among other sets of variables (Table 1). The NR1neo(−/−) mice ERPs decreased during E1 but not E5 on the stress day, and the wild-type mice did not show any change in ERP amplitude. The reduction in amplitude on the stress day occurred only during E1 in response to the S1. There was no change in S2. There was no significant interaction among epoch, stimulus, day, and genotype. To assess the consistency of responses across the five habituation days, we calculated the S1 intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient for the P20 across genotypes. The ICC was 0.89 for the P20 (F = 0.67), indicating a high degree of consistency across days.

Fig. 2.

The P20 responses to S1 and S2 for E1 and E5 are displayed for each of the habituation and stress days. Both genotypes are included. There were differences between E1 and E5 for S1 on habituation days. However, this difference was diminished during the stress day. There was no difference in any response to S2, within or across both epochs. ∗, p < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

For the P20 component of habituation trials, only the NR1neo(−/−) mice showed a reduction in amplitude during E1 on the stress day. Wild-type mice had similar peak values on the stress day compared with habituation days. ∗, p < 0.05.

N40.

There were significant main effects of genotype, stimulus, and day, but not epoch. The NR1neo(−/−) mice had significantly larger N40 ERPs than littermate controls. In addition, S1 was larger than S2 across all other variables, demonstrating gating of N40. The stress day response was smaller than the any of the habituation day responses. However, E1 and E5 responses were not significantly different.

There were significant interactions between stimulus and genotype, epoch and stimulus, epoch and day, and stimulus and day. There were no significant two-way interactions between other pairs of variables (Table 2). S1 of the NR1neo(−/−) mice was larger than S1 of the wild-type mice. However, S2 was the same for both genotypes. S1 was larger during E5 than E1, but S2 was the same for both epochs. On the stress day, E1 response decreased, whereas E5 response did not change. In addition, on the stress day, S1 decreased but the S2 remained constant, significantly impairing gating. There was no disparity between genotype across epochs, demonstrating that both genotypes reacted the same way to the long testing days. In addition, both genotypes reacted the same way across all days, suggesting that habituation and stress did not affect the genotypes differently.

There was a significant three-way interaction among epoch, stimulus, and day (Fig. 4). However, there were no significant three-way interactions among other variable groupings (Table 2). On the stress day, S1 during E1 decreased significantly to the level of S2, with a resulting loss of gating during E1stress. E5 showed no change on the stress day. There was also no significant change of S2 on the stress day. There was no difference between genotypes in their response to stress and habituation. There was no significant interaction among epoch, stimulus, day, and genotype. To assess the consistency of responses across the five habituation days, we calculated the S1 ICC coefficient for the N40 across genotypes. The ICC was 0.84 (F = 0.90), signifying a high degree of consistency across days.

Fig. 4.

For the N40 component of the habituation trials, S1 during E1 on the stress day reduced to the level of S2. There was no effect on E5 during the stress day. Both genotypes are included in the analysis. There was no difference in S2 across or within epochs. ∗, p < 0.001.

Pharmacologic Study

Chlordiazepoxide.

Grand average traces for each condition are shown in Fig. 5. Main effects and interactions, as well as their statistical values, are presented in Table 3. Chlordiazepoxide had no significant effect on the P20 of either NR1neo(−/−) or wild-type mice. However, there was a drug by genotype interaction for the N40 component (Fig. 6). There was no effect of chlordiazepoxide on N40 amplitude in NR1neo(−/−) mice, but it caused a significant increase of the N40 amplitude in wild-type controls. N40 amplitude of wild-type mice after chlordiazepoxide was similar to that of NR(−/−) mice, suggesting that increased GABAA activation may contribute to the abnormally large responses in NR1neo(−/−) mice.

Fig. 5.

Grand averages of all mice ERP recording traces after injection of chlordiazepoxide (CDP), a positive allosteric modulator at the GABAA receptor, was injected intraperitoneally at 10 mg/kg, and 0.9% saline. The P20 component did not change after drug administration, but there is an effect on N40 of wild-type mice. NR1 represents the NR1neo(−/−) mice, and WT represents wild-type mice. Chlordiazepoxide selectively increased N40 amplitude in wild-type mice.

TABLE 3 .

Chlordiazepoxide study statistical values

| F | df | p | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P20 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 9.576 | 1, 13 | 0.009 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Stimulus | 20.458 | 1, 13 | 0.0006 | S1 > S2 |

| Drug | 0.8776 | 1, 13 | 0.366 | Not significant |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 6.731 | 1, 13 | 0.022 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Drug/genotype | 0.162 | 1, 13 | 0.694 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/drug | 3.558 | 1, 13 | 0.082 | Not significant |

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/drug/genotype | 2.431 | 1, 13 | 0.143 | Not significant |

| N40 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 7.077 | 1, 13 | 0.020 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Stimulus | 57.119 | 1, 13 | <0.001 | S1 > S2 |

| Drug | 0.560 | 1, 13 | 0.468 | Not significant |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 6.618 | 1, 13 | 0.023 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Drug/genotype | 7.183 | 1, 13 | 0.019 | Wild-type CDP > wild-type saline |

| NR1neo(−/−) CDP = NR1neo(−/−) saline | ||||

| Stimulus/drug | 0.478 | 1, 13 | 0.502 | Not significant |

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/drug/genotype | 2.332 | 1, 13 | 0.151 | Not significant |

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the N40s of the two genotypes showed that chlordiazepoxide increased the amplitude of the N40 component of wild-type mice but did not significantly change N40 amplitude of the NR1neo(−/−) mice. ∗, p < 0.05.

Baclofen.

Grand average traces for each condition are shown in Fig. 7. Main effects, interactions, and statistical values are presented in Table 4. There was a significant interaction between stimulus, genotype, and drug for the P20 (Fig. 8). Baclofen had no effect on S1 in wild-type mice or S2 in either genotype. However, baclofen increased the S1 in the NR1neo(−/−) mice. There was no significant interaction of stimulus, genotype, and drug for the N40 component of ERP recording.

Fig. 7.

Grand averages of all mice ERP recording traces after injection of baclofen, a GABAB agonist injected intraperitoneally at 5 mg/kg, and 0.9% saline. The N40 did not change after drug administration; however, there is an affect on the P20. Baclofen increased P20 amplitude of NR1neo(−/−) mice only. NR1 represents the NR1neo(−/−) mice, and WT represents wild-type mice.

TABLE 4 .

Baclofen study statistical values

| F | df | p | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P20 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 16.116 | 1, 14 | 0.001 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Stimulus | 59.559 | 1, 14 | <0.001 | S1 > S2 |

| Drug | 7.010 | 1, 14 | 0.019 | BAC > saline |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 12.394 | 1, 14 | 0.003 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Drug/genotype | 4.421 | 1, 14 | 0.054 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/drug | 6.226 | 1, 14 | 0.026 | S1 BAC > S1 saline |

| S2 BAC = S2 saline | ||||

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/drug/genotype | 6.546 | 1, 14 | 0.024 | NR1neo(−/−): S1 BAC > S1 saline |

| No change in wild type or S2 response | ||||

| N40 | ||||

| Main effect | ||||

| Genotype | 19.223 | 1, 14 | 0.0006 | NR1neo(−/−) > wild type |

| Stimulus | 22.371 | 1, 14 | 0.0003 | S1 > S2 |

| Drug | 0.262 | 1, 14 | 0.617 | Not significant |

| Two-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/genotype | 28.254 | 1, 14 | 0.0001 | S1 NR1neo(−/−) > S1 wild type |

| S2 NR1neo(−/−) = S2 wild type | ||||

| Drug/genotype | 3.201 | 1, 14 | 0.095 | Not significant |

| Stimulus/drug | 0.467 | 1, 14 | 0.506 | Not significant |

| Three-way interaction | ||||

| Stimulus/drug/genotype | 2.188 | 1, 14 | 0.161 | Not significant |

Fig. 8.

Baclofen selectively increased S1 of the P20 component of ERP recordings for NR1neo(−/−) mice. It had no effect on either stimulus for the wild-type mice and no effect on S2 of the NR1neo(−/−) mice. ∗, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Although the pattern of ERPs in NR1neo(−/−) mice does not recapitulate the abnormalities in schizophrenia, the reduction of NMDA receptor expression in mice does result in behavioral abnormalities that may be informative regarding several endophenotypes of schizophrenia (Mohn et al., 1999; Bickel et al., 2008; Halene et al., 2009). The current study focused on the potential contribution of environmental stressors in mediating increased ERP amplitudes in NR1neo(−/−) mice. In addition, we examined possible pharmacotherapeutic targets using GABAA and GABAB agonists. Data suggest that changing from a familiar to a novel environment caused a reduction in both P20 and N40, which manifested in the response to the first stimulus response only. Although neither of the drugs tested reduced ERP amplitude, we found that NR1neo(−/−) mice exhibited reduced sensitivity to GABAA and increased sensitivity to GABAB-selective agents.

We hypothesized that NR1neo(−/−) mice would habituate to a familiar environment, possibly by reducing the stress of testing, and attenuating the elevated ERP amplitude. We also hypothesized that this habituation could be reversed by presenting a novel testing environment as a stressor. However, there was no change in ERP amplitude between the habituation days, suggesting that the increased ERP amplitude in NR1neo(−/−) mice represents a constant trait rather than an easily modified state induced by environmental factors such as stress. These data indicate that underlying functional neuronal changes in NR1neo(−/−) mice persist despite environmental changes. Furthermore, ICC coefficients for P20 and N40 suggest that ERPs were extremely stable throughout the study, indicating that ERPs are a reliable measurement of brain activity. However, increased ERP amplitudes in NR1neo(−/−) mice are not entirely consistent with a previous ERP study in this strain that found modest gating deficits in NR1neo(−/−) mice due to an increased response to the second stimulus (Bickel et al., 2008). The authors note that these changes are not typical for patients with schizophrenia, in which impaired gating is more commonly observed due to a decreased response to the first tone (Freedman et al., 1983; Jin et al., 1997; Clementz and Blumenfeld, 2001; Halene et al., 2009). There are several possible reasons for different findings between these studies. The previous study used 3-month-old male and female mice, whereas this study used males between 2 and 6 months of age. Electrode configuration also varied as the previous study recorded from surface electrodes, yielding lower peak amplitudes, in comparison with the current study in which one recording electrode is placed in hippocampus. Type and characteristics of the electrodes used (e.g., impedance) also varied and may influence the recording of electric brain activity. Finally, the previous study used ketamine (100 mg/kg) anesthesia for electrode placement, whereas the current study used isoflurane. Previous studies indicate that ketamine causes long-term adaptation of ERPs and hippocampal cell death (Maxwell et al., 2006b; Majewski-Tiedeken et al., 2008). Although changes in the current study were due entirely to S1, we report both S1 and S2 responses for comparison with the human literature, in which many studies report S1 and S2.

The stress day had different effects on the P20 and N40. For the P20 component, S1 did not differ between epochs during habituation. This was in contrast to the reduction in P20 amplitude that occurred during E5 on habituation days. In addition, only NR1neo(−/−) mice had decreased P20 during E1 on the stress day. One possible explanation is that the NR1neo(−/−) mice showed an increased sensitivity to stress caused by a novel environment. Alternatively, changes may have been due to differences in selective attention. Previous studies indicate that the human N100 is more responsive to attentional manipulations than the P50, which seems less affected by the psychological state of the subject tested (White and Yee, 1997; Yee and White, 2001). Because we could not assess serum corticosterone levels on each test day without adding an additional stressor, it is not possible to distinguish the effects of stress and selective attention on the mouse correlates of P50 and N100.

There was no four-way interaction between genotype, day, epoch, and stimulus, suggesting that the stress of a novel environment did not effect gating of the P20 differently in NR1neo(−/−) mice. For the N40 component, S1 was reduced to the level of S2 during E1 on the stress day. This indicates that the novel environment caused a loss of N40 gating. Consistent with these findings, previous data indicate that gating abnormalities can be largely attributed to a reduced response to S1 rather than a failure to inhibit responses to S2 (Clementz and Blumenfeld, 2001). However, S1 increased and gating was restored for E5 on the stress day. This suggests that the mice were able to habituate to the novel environment over the course of testing (approximately 3 h). There is previous evidence that corticosterone contributes to stress-induced elevation of extracellular glutamate in the hippocampus (Lowy et al., 1993; Moghaddam et al., 1994). Although low-dose corticosterone increases N40 amplitude and gating, at higher doses of corticosterone, N40 amplitude is decreased and gating is diminished. There were no effects of corticosterone on the P20 component in the previous study (Maxwell et al., 2006a). The current study is consistent with this finding because presumably high levels of stress upon exposure to a novel environment decreased N40 amplitude and diminished gating. However, N40 amplitude and gating were restored after habituation, consistent with the idea that initial stress associated with the novel environment was diminished. The effect of stress on the early auditory processing was limited to S1 during E1 for both the P20 and N40. No significant differences were found on S2 for either component. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that deficits in gating are primarily a function of changes in the first stimulus response of mice (Connolly et al., 2003; Halene and Siegel, 2008).

Habituation did not decrease the abnormally large ERPs in NR1neo(−/−) mice. However, NR1neo(−/−) mice showed increased vulnerability to the effects of a stressful environment on the P20, and both genotypes had reduced N40 gating upon exposure to the novel environment. Habituation reversed both of these effects. Subsequently, we tested two pharmacological approaches to determine whether the effects of genotype could be modulated by increasing activity at GABAA or GABAB receptors. GABA agonists were hypothesized to reduce the abnormally large ERP amplitude in NR1neo(−/−). NMDA receptors activate GABA interneurons that are predominantly inhibitory in nature (Farber, 2003). Therefore, we hypothesized that reduced NMDA receptor activity in NR1neo(−/−) mice would result in a loss of inhibitory tone, causing increased ERP amplitude. We proposed that GABA agonists would directly stimulate GABA receptors and restore inhibitory tone. Although a reduction in ERP amplitude of NR1neo(−/−) mice was not accomplished, there was a difference in effects of GABAA and GABAB agonists in each genotype. The GABAA positive allosteric modulator chlordiazepoxide increased N40 amplitude in wild-type mice but not NR1neo(−/−) mice. The GABAB agonist baclofen increased the P20 response to S1 in NR1neo(−/−) mice. However, there was no P20 change in the wild-type mice or S2 for either genotype. Although only a single dose of each compound was administered, the observation that the tested doses had an effect on genotype indicates that there is a differential sensitivity at the doses tested. The mechanisms by which GABAA and GABAB receptors are differentially affected by NMDA receptor reduction remain elusive. However, previous data show that the function of GABAA receptors is affected by the activation of NMDA receptors. Calcium entering the cell through NMDA channels serves as a messenger linking the function of NMDA and GABAA receptors. Activation of NMDA receptors increases intracellular calcium levels and suppresses GABAA induced response (Chen and Wong, 1995). One possible explanation relates to differences in pre- and postsynaptical localization of GABAA and GABAB receptors. GABAB has a direct effect on dopamine release due to its proximity to presynaptic dopamine terminals. GABAA are thought to work primarily postsynaptically via interneurons (Smolders et al., 1995). It is interesting that NMDA receptors are localized on both presynaptic dopamine terminals and on GABA interneurons where they inhibit presynaptic dopamine release through local feedback regulation (Hernández et al., 2003; Schiffer et al., 2003).

The NR1neo(−/−) mice lack approximately 90% of the normal amount of NMDA NR1 subunit; therefore, they may have reduced suppression of GABAA response mediated by calcium influx through NMDA receptors. This is consistent with our finding that NR1neo(−/−) mice showed decreased sensitivity to the GABAA positive allosteric modulator chlordiazepoxide. In addition, GABAA and GABAB receptors are functionally coupled, suggesting that alterations in GABAA receptors may mediate the increased sensitivity to the GABAB agonist baclofen in NR1neo(−/−) mice (Kardos et al., 1994). Paradoxically, there was an increase in ERP amplitude due to both GABAergic agonists. ERPs result from the coordinated firing of groups of neurons throughout the brain that converge to yield a visible signal against the background of unrelated activity, i.e., noise. Few studies have investigated the role of GABA systems on the P1 (human P50 and mouse P20) or N1 (human N100 and mouse N40) ERPs (Ray et al., 1992; Curran et al., 1998). Our data suggest that activation of GABAergic systems may contribute to coordinated patterns of neuronal activity throughout the brain that underlie ERP components. Further studies could investigate differential responses to each drug between genotypes. This is of interest because multiple lines of investigation suggest that NMDAR hypofunction in schizophrenia is largely mediated through NMDA receptors located on GABAergic interneurons (Gonzalez-Burgos and Lewis, 2008; Hashimoto et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2008a,b).

There are several limitations to the current work. Results were obtained from mice with constitutive reduction in NR1. Therefore, compensatory alterations during development may contribute to the observed phenotypes. Future studies could examine emergence of the observed phenotypes during development and/or use conditional NR1neo(−/−) mice to alter NMDA NR1 expression at various time points. Furthermore, data in mice are limited in how extensively they can be applied to complex psychiatric disorders in humans. However, ERPs are highly conserved across species, suggesting that the role of specific proteins or systems to ERP abnormalities may be informative for human disease states (Connolly et al., 2003; Siegel et al., 2003). In summary, current data suggest that a reduction in NMDA NR1 may increase vulnerability to the effects of stress on some brain regions as evidenced by the P20 and that GABAA and GABAB receptor systems may have selective interactions with NMDA receptor abnormalities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sybil O’Connor and Tanya West for an excellent animal care and Amanda Williams for the genotyping. We thank Dr. Beverly Koller for making NR1neo(−/−) mice available.

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant 5R01-DA02321002]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute for Mental Health [Grants P50-MH064045, R01-MH080718]; the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant P50-CA084718]; the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [Grant IRTG 1328]; and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

- NMDAR

- N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor

- NR1

- N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit 1

- NMDA

- N-methyl-d-aspartate

- ERP

- event-related potential

- WT

- wild type

- qPCR

- quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- S1/S2

- stimulus 1/stimulus 2

- E1/E5

- epoch 1/epoch 5

- P20

- positive deflection at 20 ms

- P20

- positive deflection at 20 ms

- N40

- negative deflection at 40 ms

- ICC

- interclass correlation

- P50

- positive deflection at 50 ms

- N100

- negative deflection at 100 ms.

References

- Bickel S, Lipp HP, Umbricht D. ( 2008) Early auditory sensory processing deficits in mouse mutants with reduced NMDA receptor function. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 1680–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. ( 1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QX, Wong RK. ( 1995) Suppression of GABAA receptor responses by NMDA application in hippocampal neurones acutely isolated from the adult guinea-pig. J Physiol (Lond) 482: 353–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz BA, Blumenfeld LD. ( 2001) Multichannel electroencephalographic assessment of auditory evoked response suppression in schizophrenia. Exp Brain Res 139: 377–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly PM, Maxwell C, Liang Y, Kahn JB, Kanes SJ, Abel T, Gur RE, Turetsky BI, Siegel SJ. ( 2004) The effects of ketamine vary among inbred mouse strains and mimic schizophrenia for the P80, but not P20 or N40 auditory ERP components. Neurochem Res 29: 1179–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly PM, Maxwell CR, Kanes SJ, Abel T, Liang Y, Tokarczyk J, Bilker WB, Turetsky BI, Gur RE, Siegel SJ. ( 2003) Inhibition of auditory evoked potentials and prepulse inhibition of startle in DBA/2J and DBA/2Hsd inbred mouse substrains. Brain Res 992: 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran HV, Pooviboonsuk P, Dalton JA, Lader MH. ( 1998) Differentiating the effects of centrally acting drugs on arousal and memory: an event-related potential study of scopolamine, lorazepam and diphenhydramine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 135: 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GE, Moy SS, Perez A, Eddy DM, Zinzow WM, Lieberman JA, Snouwaert JN, Koller BH. ( 2004) Deficits in sensorimotor gating and tests of social behavior in a genetic model of reduced NMDA receptor function. Behav Brain Res 153: 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber NB. ( 2003) The NMDA receptor hypofunction model of psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1003: 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman R, Adler LE, Waldo MC, Pachtman E, Franks RD. ( 1983) Neurophysiological evidence for a defect in inhibitory pathways in schizophrenia: comparison of medicated and drug-free patients. Biol Psychiatry 18: 537–551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior M, Kaminski R, Witkin JM. ( 2004) Pharmacological modulation of GABA(B) receptors affects cocaine-induced seizures in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 174: 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA. ( 2008) GABA neurons and the mechanisms of network oscillations: implications for understanding cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 34: 944–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halene TB, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Christian EP, Jonak GJ, Gur TL, Blendy JA, Dow HC, Brodkin ES, Schneider Fet al. ( 2009) Assessment of NMDA receptor NR1 subunit hypofunction in mice as a model for schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav, doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00504.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halene TB, Siegel SJ. ( 2008) Antipsychotic-like properties of phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors: evaluation of 4-(3-butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidazolidinone (R0–20-1724) with auditory event-related potentials and prepulse inhibition of startle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326: 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Bazmi HH, Mirnics K, Wu Q, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. ( 2008) Conserved regional patterns of GABA-related transcript expression in the neocortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 165: 479–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández LF, Segovia G, Mora F. ( 2003) Effects of activation of NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors on the extracellular concentrations of dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA in striatum of the awake rat: a microdialysis study. Neurochem Res 28: 1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen LM, Gispen-de Wied CC, Kahn RS. ( 2000) Selective impairments in the stress response in schizophrenic patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 149: 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. ( 1991) Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 148: 1301–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Potkin SG, Patterson JV, Sandman CA, Hetrick WP, Bunney WE., Jr ( 1997) Effects of P50 temporal variability on sensory gating in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 70: 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardos J, Elster L, Damgaard I, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Schousboe A. ( 1994) Role of GABAB receptors in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and possible interaction between GABAA and GABAB receptors in regulation of transmitter release in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci Res 39: 646–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. ( 1995) The structure of the genetic and environmental risk factors for six major psychiatric disorders in women. Phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, bulimia, major depression, and alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 374–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. ( 2001) Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 25: 455–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Cho RY, Carter CS, Eklund K, Forster S, Kelly MA, Montrose D. ( 2008a) Subunit-selective modulation of GABA type A receptor neurotransmission and cognition in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 165: 1585–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Morris HM. ( 2008b) Cell and receptor type-specific alterations in markers of GABA neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Neurotox Res 14: 237–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy MT, Gault L, Yamamoto BK. ( 1993) Adrenalectomy attenuates stress-induced elevations in extracellular glutamate concentrations in the hippocampus. J Neurochem 61: 1957–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski-Tiedeken CR, Rabin CR, Siegel SJ. ( 2008) Ketamine exposure in adult mice leads to increased cell death in C3H, DBA2 and FVB inbred mouse strains. Drug Alcohol Depend 92: 217–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CR, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Gettes DR, Evans DL, Kanes SJ, Abel T, Karp J, Siegel SJ. ( 2006a) Corticosterone modulates auditory gating in mouse. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CR, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Trief D, Kanes SJ, Karp J, Siegel SJ. ( 2006b) Ketamine produces lasting disruptions in encoding of sensory stimuli. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316: 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Bolinao ML, Stein-Behrens B, Sapolsky R. ( 1994) Glucocorticoids mediate the stress-induced extracellular accumulation of glutamate. Brain Res 655: 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn AR, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, Koller BH. ( 1999) Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell 98: 427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RM, Malla AK. ( 1993) Stressful life events and schizophrenia. I: a review of the research. Br J Psychiatry 162: 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. ( 1998) The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol Sci 19: 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PG, Meador KJ, Loring DW. ( 1992) Diazepam effects on the P3 event-related potential. J Clin Psychopharmacol 12: 415–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Davies B, Shore R. ( 2002) Absence of anxiolytic response to chlordiazepoxide in two common background strains exposed to the elevated plus-maze: importance and implications of behavioural baseline. Genes Brain Behav 1: 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer WK, Logan J, Dewey SL. ( 2003) Positron emission tomography studies of potential mechanisms underlying phencyclidine-induced alterations in striatal dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 2192–2198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SJ, Connolly P, Liang Y, Lenox RH, Gur RE, Bilker WB, Kanes SJ, Turetsky BI. ( 2003) Effects of strain, novelty, and NMDA blockade on auditory-evoked potentials in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 675–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders I, De Klippel N, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. ( 1995) Tonic GABA-ergic modulation of striatal dopamine release studied by in vivo microdialysis in the freely moving rat. Eur J Pharmacol 284: 83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PM, Yee CM. ( 1997) Effects of attentional and stressor manipulations on the P50 gating response. Psychophysiology 34: 703–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee CM, White PM. ( 2001) Experimental modification of P50 suppression. Psychophysiology 38: 531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukin RS, Bennett MV. ( 1995) Alternatively spliced isoforms of the NMDARI receptor subunit. Trends Neurosci 18: 306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]