Abstract

Although oral health care providers (OHP) are key in the secondary prevention of eating disorders (ED), the majority are not engaged in assessment, referral, and case management. This innovative pilot project developed and evaluated a web-based training program for dental and dental hygiene students and providers on the secondary prevention of ED. The intervention combined didactic and skill-based objectives to train OHP on ED and its oral health effects, OHP roles, skills in identifying the oral signs of ED, communication, treatment, and referral. Using a convenience sample of OHP (n=66), a pre-/post-test evaluated short-term outcomes and user satisfaction. Results revealed statistically significant improvements in self-efficacy (p<.001); knowledge of oral manifestations from restrictive behaviors (p<.001) and purging behaviors (p<.001); knowledge of oral treatment options (p<.001); and attitudes towards the secondary prevention of ED (p<.001). Most participants strongly agreed or agreed that the program provided more information (89 percent) and resources (89 percent) about the secondary prevention of ED than were currently available; 91 percent strongly agreed or agreed that they would access this program for information regarding the secondary prevention of ED. This pilot project provides unique training in the clinical evaluation, patient approach, referral, and oral treatment that takes a multidisciplinary approach to address ED.

Keywords: eating disorders, dentistry, dental education, dental hygienists, students, dental, oral health, knowledge, attitudes

Within the last four decades, the incidence and prevalence of eating disorders in the United States increased considerably.1 Specifically, the incidence of bulimia nervosa in ten- to thirty-nine-year-old women tripled between 1988 and 1993.2 A recent epidemiological review of eating disorders indicated 1–2 percent of young women will be affected by bulimia nervosa during their lifetime.3 Disordered eating behaviors such as excessive dieting, vomiting, or use of diuretics and/or laxatives occur at higher rates than anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, with an estimated prevalence of 10 percent in adolescent girls and women.4 These sub-threshold cases account for the majority of all cases of eating disorders.3 Since evidence suggests a progression from sub-threshold disordered eating behaviors to bulimia nervosa, early detection and referral for treatment are crucial,5 signifying the need for training health care providers to improve their capabilities for early detection of eating disorders.3

Secondary prevention increases the likelihood of recovery for individuals with eating disorders.6 Secondary prevention consists of early detection of disordered eating behaviors and their physical and oral manifestations, and includes all measures that can modify the severity or extent of the problem (i.e., referral for care, patient-specific oral treatment).7 The crucial role of secondary prevention is significant for reducing oral and medical complications associated with eating disorder behaviors, decreasing health care costs, and increasing quality of life among those suffering with eating disorders. Unfortunately, only one in ten individuals with eating disorders receives treatment,8 so the training and implementation of dental professionals in secondary prevention could have a significant impact on this health issue.

Dentists and dental hygienists could potentially play a fundamental role in the secondary prevention of eating disorders. They are often the first health professionals to observe the overt health effects of eating disorders and, therefore, may be the first health care provider in the process of problem identification and referral.9–13 Although dentists believe they have an ethical obligation to participate in the secondary prevention of eating disorders—and despite the potential benefits to their patients’ well-being14—the majority of oral health practitioners do not engage in such clinical behaviors.15–17

A long-standing issue in oral health education has been preparing clinicians to address public health issues that pose threats to oral health.18–20 Dental faculty members have indicated that important but sensitive public health problems (e.g., eating disorders or physical abuse) are not typically covered in the curriculum or in clinical education in appropriate depth.21–26 For example, DeBate et al.27 discovered low levels of knowledge about the oral and physical cues of anorexia nervosa and the physical cues of bulimia nervosa among oral health practitioners.

Essential communication skills that provide the building blocks for training dentists in these sensitive and complex areas are not adequately integrated within many dental schools.28 With regard to secondary prevention of eating disorders, recent studies have found that training oral health professionals in such practices as assessment, patient approach/communication, behavior change strategies, and referral resources is lacking in their educational preparation.14,16,17,27,29 Possible solutions include increasing training and education in dental and dental hygiene programs to include eating disorder-specific secondary prevention in their respective curricula. In a study of the breadth and depth of dental and dental hygiene curricula with regard to secondary prevention of eating disorders, results revealed more dental hygiene programs (97 percent) than dental schools (79 percent) include eating disorders in their curricula (p=.003). Moreover, about twenty-six minutes of didactic instruction and only six to nine minutes of clinical instruction were spent on this topic in either dental or dental hygiene programs.29

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, numerous calls for change have been made regarding the future direction of the dental curriculum.20,30–33 Consistently advocated changes include a) increased educational collaboration between dentistry and the other health professions featuring an integration of dental and medical health issues; b) student exposure to patients and their oral health and systemic medical problems from the first day of the curriculum to the last; c) evidence-based approaches to clinical decision making; d) shifting the burden of learning to the student by presenting more independent learning opportunities; and e) increased utilization of computer-based and web-based information technology. 20,34 In addition, there has been growing support and adoption of electronic curricula (e-curricula) in dental and dental hygiene education in addition to continuing education opportunities.35–38 “E-curriculum” refers to educational technologies that support the development and delivery of web, computer, or network-based learning.38,39 The incorporation of web-based learning into the dental curriculum has been strongly encouraged by the American Dental Education Association (ADEA) with specific recommendations “to create new opportunities for distance learning in dental education” and “to use information technology to enrich student learning.”19,38 Examples of current dental e-curricula include dental terminology, oral manifestations of systemic illnesses, diagnosis and treatment, clinical simulations, and complete distance education programs.36,40–46

The lack of appropriate eating disorder-specific curricular content coupled with the recommendation for e-curricula supports the need for the development of a web-based training program to bridge current research and technology both into practice and into the dental curriculum. Consequently, we produced a prototype web-based training program to increase the capacity of oral health professionals to deliver eating disorder-specific secondary prevention to patients suspected of disordered eating behaviors. We conducted a pilot evaluation of the program and assessed the extent to which oral health professionals and trainees would gain improved knowledge, attitudes, and skills with regard to the secondary prevention of eating disorders.

Methods

Design Overview

As depicted in Table 1, the design of this intervention spanned two phases: 1) web development and usability testing, and 2) pilot evaluation.

Table 1.

Intervention development phases of the web-based training program

| Study Phase | Format | Sample | Results and Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Website Development and Usability Testing | |||

| Website content development | |||

| Developmental evaluation | Four 1-hour focus groups | Dental students (n=16) and dental hygiene students (n=20) |

|

| Tailor website | |||

| Usability testing | 1-hour independent review of website with participant observer | Dentist (n=1), dental hygiene instructors (n=2), and dental hygiene students (n=2) |

|

| Phase II: Pilot Evaluation | |||

| Impact evaluation | 1-week independent review of website with pre- and post-test | Dentists (n=4), dental hygienists (n=4), dental students (n=42), and dental hygiene students (n=14) |

|

Phase I: web development and usability testing

To design a web-based program specifically for oral health providers that would be comprehensive in scope and relevant to our target audience, we used data gathered from previous formative research14,17,27,29 and media projects aimed at dental professionals (e.g., Helping Your Patients Quit Tobacco, 2005) conducted by several of the authors. During an extensive design phase, the project team outlined a navigational structure for the program and created content modules that delivered information on eating disorders and their oral health effects, the role of the oral health care provider, and skills in the identification of oral findings of eating disorders, patient approach, and patient-specific treatment.

After the design of the web-based prototype was complete, an iterative development process was initiated for creating the website. During this stage, the technology group designed the user interface, created a “look and feel” for the program, acquired still photographs and other images, edited video segments, designed the underlying database, and performed all the programming tasks required to develop a fully functioning website. As part of this process, several iterations of the program were generated and circulated to members of the project team. A number of enhancements to the website were made during this period, including modifications to the navigation and user interface, content edits, and improvements in the overall functionality of the program. Once the Alpha version of the website was completed, a developmental evaluation was implemented using focus group methodology to solicit recommendations for product improvement prior to the usability testing and pilot evaluation. The focus groups were conducted among a convenience sample (n=36) comprised of dental students from the University of Illinois at Chicago and dental hygiene students from Kennedy King Community College (Chicago, IL) and Santa Fe College (Gainesville, FL). Focus group participants viewed the program and were asked general questions pertaining to graphic interface design, visibility, organization, and relevance of topics, in addition to specific questions regarding organization, content, and comprehension of material. Based on responses from these focus groups, changes were made to tailor the program content and website interface for use among dental and dental hygiene students.

Usability tests were then conducted with a convenience sample (n=5) of dentists, dental hygiene instructors, and dental hygiene students in Eugene, Oregon, to determine how the program functioned with the two educational audiences (oral health providers and oral health students) and to focus on any problems related to the form or content. We met with these participants individually and asked them to complete several navigational tasks on the website (e.g., finding a specified content area or completing a module quiz) while a program staff member trained in usability testing observed and noted areas of difficulty or confusion. A more extensive interview followed immediately afterwards to assess what participants liked or did not like and to determine how effectively the program delivered the content and training.

Phase II: pilot evaluation

After final changes were made to the training program, a pilot evaluation was conducted. The main objectives of the pilot evaluation were to address consumer satisfaction and short-term impacts of the program. The following paragraphs present the methods, results, and discussion of the pilot evaluation.

A two-group non-experimental pre-/post-design was used for the pilot evaluation. The pre-/post-evaluation utilized a convenience sample (n=66) of dental students from the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Florida, dental hygiene students from Lane Community College in Eugene, Oregon, and dentists and dental hygienists who practiced in Eugene, Oregon. Seventy-seven participants completed the pretest, and sixty-six participants completed the posttest, resulting in an 86 percent response rate. No statistically significant differences occurred by occupation (p=.075). Table 2 depicts demographic characteristics of the evaluation participants who completed both the pre- and post-tests. The majority of participants were dental students followed by dental hygiene students, dentists, and dental hygienists. The majority of participants were female and Caucasian or Asian. The mean age reported by participants was twenty-seven.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of pilot evaluation participants (n=66)

| Variable | Dentist f (%) |

Dental Hygienist f (%) |

Dental Student f (%) |

Dental Hygiene Student f (%) |

Total Sample f (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0) | 11 (26.2%) | 0 (0) | 13 (20.0%) |

| Female | 3 (60.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 31 (73.8%) | 14 (100.0%) | 52 (80.0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 2 (40.0%) | 3(75.0%) | 27 (64.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 44 (67.7%) |

| African American | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.1%) | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (7.7%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (3.0%) |

| Asian | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 10 (23.8%) | 0 (0) | 12 (18.5%) |

| Other | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.0%) |

| Age m ±sd | 27.80 ±4.82 | 33.00 ±16.83 | 25.12 ±4.40 | 29.86 ±7.05 | 26.83 ±6.60 |

Note: Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

The participants were recruited via invitational flyers. All interested participants were instructed to provide their name, email address, and telephone number to the evaluation coordinator. The evaluation coordinator emailed all interested participants with instructions for participation, the web address (URL), and participant code number. All participants were instructed to first read a project description and then register for the evaluation by using the participant code number and creating a password for entry. Once registered, participants were directed to an eleven-item pre-assessment. After completing the pre-assessment, participants were directed to the training program. All participants had one week to view the training program. At the end of the one-week period, participants were instructed to complete the post-assessment. After completing an eight-item post-assessment instrument, participants received confirmation of completion. To increase involvement, each participant received a $40 stipend. This study was given exempt status by the principal investigator’s university human subjects Institutional Review Board as it met criteria for federal exemption.

Website Content

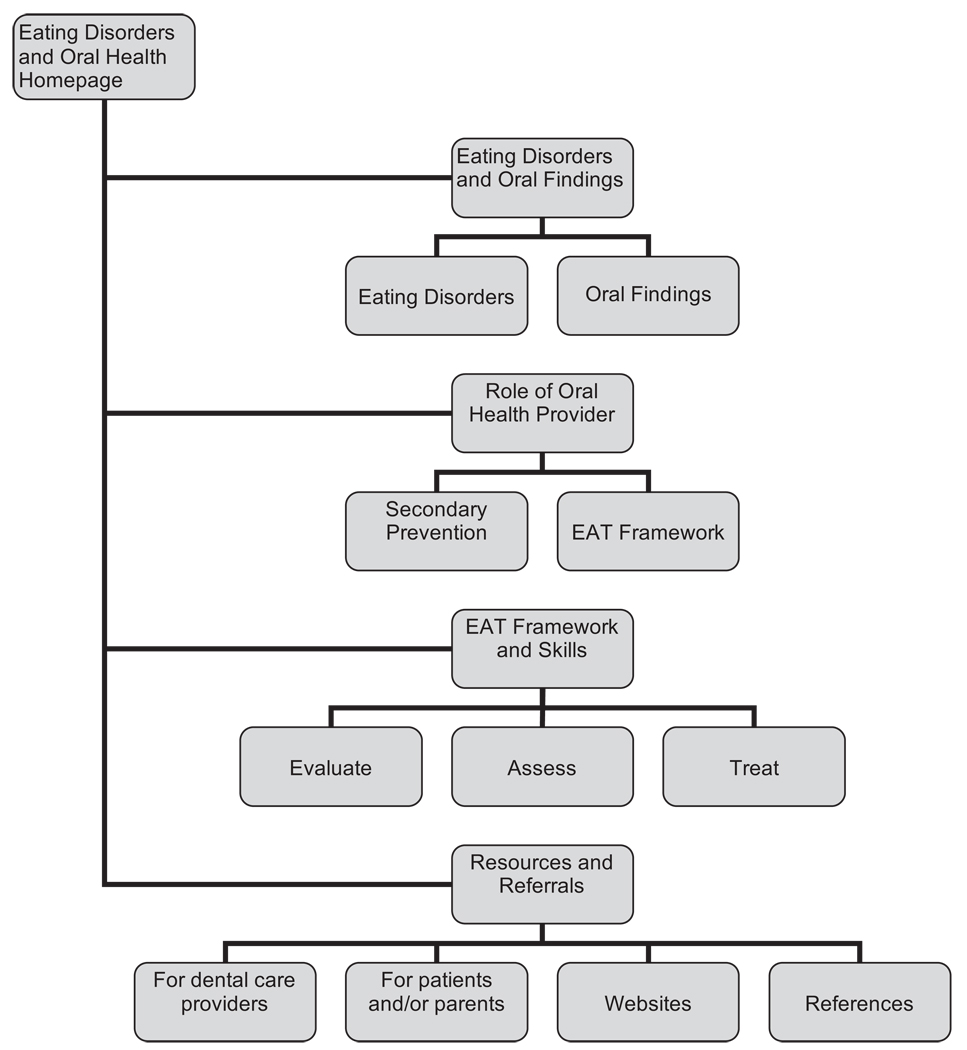

The web-based training program combines didactic and skill-based objectives using scripts, storyboards, graphics, videos, flowcharts, and text to create an appealing interface to train oral health providers about secondary prevention of eating disorders. The program utilizes a framework for secondary prevention of eating disorders based upon the transtheoretical model47 and brief motivational interviewing.48 The program is divided into four main areas: Eating Disorders and Oral Findings, the Role of the Oral Health Provider, EAT Framework (Evaluate, Assess, Treat) and Skills, and Resources and Referrals. The design and overview of the resulting “Eating Disorders and Oral Health” website is shown in Figure 1, and key features of each module of the site are summarized below.

Figure 1.

Map of the “Eating Disorders and Oral Health” intervention website

Eating Disorders and Oral Findings

This module is divided into two main components: Eating Disorders and Oral Findings. Within Eating Disorders, the user can learn about the three main types of eating disorders, which are anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS). For each type of eating disorder, further information about diagnostic criteria, warning signs, and health consequences is provided. The Oral Findings section describes the intra- and extraoral findings commonly associated with disordered eating behaviors, each categorized as a sign of malnutrition, dehydration, or vomiting. Each oral finding is described within a graphically distinct printer-friendly “pop-up” table with descriptions of each oral finding, a picture example, an explanation of common causes, assessment techniques, and examples of initial and follow-up questions to ask a patient exhibiting this particular oral sign.

Role of Oral Health Provider

This module contains two components: Secondary Prevention and EAT Framework. The Secondary Prevention section defines secondary prevention and describes the fundamental role dentists and dental hygienists play in the secondary prevention of eating disorders. Examples of activities associated with secondary prevention of eating disorders that can improve the likelihood of early recovery and improved quality of life in patients exhibiting symptoms of eating disorders are also provided. Within the EAT Framework section, the user is introduced to a three-step patient approach—Evaluate, Assess, Treat. Text screens and graphic images are used in this section to encourage users to engage in secondary prevention practices associated with eating disorders. This module also addresses the sensitive nature of this health issue. The user can learn about the theories and evidence-based aspects behind the development of this three-step approach, which includes previous formative research, the stages of change construct of the transtheoretical model,47 and brief motivational interviewing.48

EAT Framework and Skills

This module is the critical skill-based portion of the program. It is divided into the three steps of the EAT framework (Evaluate, Assess, Treat): 1) evaluating patients presenting signs of disordered eating behaviors; 2) assessing patient readiness for managing disordered eating behaviors; and 3) treatment strategies based upon the patient’s stage of readiness.

The Evaluate section focuses on how to evaluate patients presenting with signs of disordered eating behaviors through comprehensive data collection and differential diagnosis (i.e., determining if the oral finding is caused by behaviors associated with disordered eating or another cause). More specifically, the steps within the Evaluate section are further divided into specific sequential behaviors consisting of a) establish rapport; b) collect data; c) set agenda; d) discuss etiology; e) discuss behaviors; and f) summarize outcome. These steps are based on the conceptual framework of brief motivational interviewing48 and have the objective of eliciting sensitive information from the patient without offending or breaching the patient’s trust. This includes text screens, corresponding flowcharts, sample staging questions to ask patients at each step, and a realistic video vignette of a patient-dental provider interaction to demonstrate each step.

Based on the concepts of brief motivational interviewing,48 the Assess section presents information that describes how dental professionals can assess a patient’s stage of readiness to address his or her disordered eating behavior. The user can learn an easy and nonconfrontational scaling technique (on a scale of 1–5) to determine how important it is to the patient to address his or her disordered eating behavior and how confident the patient is in taking the next step to change the behavior. The Assess skills are conveyed through the use of text screens, user-friendly flowcharts, graphic information to demonstrate skills, sample questions for determining patient readiness, and a video example to depict the step in action.

In the Treat section, the user can learn how to deliver patient-specific treatment tailored to a patient’s stage of readiness as determined in the Assess step. We provide separate treatment plans for each stage of patient readiness: Not Ready, Almost Ready, and Ready. Treatment plans for patients currently seeking mental health treatment for an eating disorder and for patients who have relapsed to disordered eating behaviors are also provided. Each treatment plan is presented in a printer-friendly table with a patient profile, treatment options, and detailed instructions on how to provide patient-specific treatment. A video demonstration of how to appropriately deliver a treatment plan that is both well suited to a patient’s needs and likely to be followed by the patient at his or her stage of readiness is also provided. At the end of this module, there is a video vignette that illustrates all of the steps in action (Evaluate, Assess, Treat), so dental professionals can view the entire EAT framework in practice.

Resources and Referrals

This module is divided into four main components: a) information for dental care providers; b) information for patients/parents; c) websites; and d) references. This section serves as a resource library, providing the user with printer-friendly handouts and links to websites for general information and treatment information on eating disorders and oral health. Also included are links to websites that allow dental professionals to find local doctors, nutritionists, mental health care providers, and in-patient and outpatient facilities.

Measures

A web-based Likert-type instrument was used to assess the short-term impacts of the program. The health belief model49 served as the conceptual framework for the assessment of participant knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy pertaining to the following criterion-specific secondary prevention behaviors: a) identification of oral manifestations related to disordered eating behaviors; b) patient-specific treatment of oral manifestations; c) patient referral; and d) case management.

Attitudes pertaining to secondary prevention behaviors comprised seven items with a four-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) that were calculated as sum score. Scores ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating positive attitudes towards secondary prevention of eating disorders. Sum scores were based on the following statements:

Eating disorders are serious health issues;

Dental professionals have a professional responsibility to identify patients with oral findings associated with disordered eating behaviors;

Dental professionals have a professional responsibility to refer patients who present with oral findings associated with eating disorders;

Dental professionals have a legal responsibility to identify patients with oral findings associated with disordered eating;

Dental professionals have a legal responsibility to refer patients suspected of engaging in disordered eating behaviors;

Liability in identifying patients with eating disorders is an emerging health issue in dentistry; and

Liability in referring patients with eating disorders is an emerging health issue in dentistry.

Knowledge of oral manifestations of anorexia nervosa was calculated as a percent score indicating the percent of correct responses to the following question: How likely is each of the following possible outcomes to be observed in at least a minority of patients with restrictive eating behaviors associated with an eating disorder (response categories were Likely or Unlikely)? The list of outcomes included angular cheilitis, candidiasis, cracked and/or dry nails, dental caries, oral mucosal ulceration, glossitis, lanugo, parotid gland enlargement, perimolysis/dental erosions, periodontal disease, Russell’s finger, tooth sensitivity, trauma to the soft palate/soft palate ulceration, xerostomia, and extreme thinness.

Knowledge of oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa was also calculated as a percent score indicating the percent of correct responses to the following question: How likely is each of the following possible outcomes to be observed in at least a minority of patients with purging behaviors associated with an eating disorder (response categories were Likely or Unlikely)? The list of outcomes included angular cheilitis, candidiasis, cracked and/or dry nails, dental caries, oral mucosal ulceration, glossitis, lanugo, parotid gland enlargement, perimolysis/dental erosions, periodontal disease, Russell’s finger, tooth sensitivity, trauma to the soft palate/soft palate ulceration, xerostomia, and extreme thinness.

Knowledge of oral treatment for oral manifestations of disordered eating behaviors was calculated as a percent score indicating the percent of correct responses to the following question: How effective or ineffective is each of the following measures in preventing a person with disordered eating from further physical damages (response categories were Effective or Not effective)? The list of measures included not brushing teeth after vomiting, rinsing mouth with alkaline solution after vomiting, addressing the clinical concerns and dental implications with the patient, indicating dental implications to the patient’s physician or other health care provider, arranging for a more frequent recall program, addressing your concern with the patient who exhibits symptoms of disordered eating, and making a referral for a patient who shows signs of disordered eating.

Self-efficacy comprised seven items with a four-point Likert-type scale (very easy to very difficult) that were calculated as sum score. Scores ranged from 7 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Sum scores were based on the following activities pertaining to the following question: How easy or difficult would it be for you to … a) provide the following secondary prevention care for patients indicative of disordered eating; b) approach a patient who presents with oral manifestations associated with disordered eating behaviors; c) approach the parent of a patient who presents with oral manifestations associated with disordered eating behaviors; d) offer the patient specific preventive home dental care instructions; e) arrange a more frequent recall program; f) make a referral for treatment; g) initiate correspondence with the patient’s physician or other health care provider; and h) participate in case management with the patient’s physician or other health care provider.

Questions on participants’ demographic characteristics including gender, race, age, and occupation were also included on the eleven-item pre-assessment. The eight-item post-assessment included the same questions as the pre-assessment except for the demographic variables (four items). The post-assessment also included a category regarding participant satisfaction that was based on constructs of diffusion of innovations,50 which included characteristics of innovations that affect adoption and diffusion (e.g., relative advantage, complexity, trialability).

Results

As depicted in Table 3, statistically significant changes were observed from pre- to post-intervention across all variables: self-efficacy (p<.001); knowledge of oral manifestations from restrictive disordered eating behaviors (p<.001) and purging disordered eating behaviors (p<.001); knowledge of treatment options for patients suspected of engaging in disordered eating behaviors (p<.001); and attitudes towards secondary prevention of eating disorders (p<.001). Additionally, the percentage of participants in the evaluation sample who correctly distinguished the main types of eating disorders substantially increased from 21 percent of participants before the training to 91 percent of participants after the training was completed.

Table 3.

Mean differences in self-efficacy and knowledge of oral manifestations and oral treatment of pilot evaluation participants from pre- to post-intervention (n=66)

| Variable | Pre-intervention m ±sd |

Post-intervention m ±sd |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | 13.30 ±03.75 | 16.77 ±03.19 | <.001 |

| Knowledge of oral manifestations from restrictive disordered eating behaviors | 57.47 ±13.78 | 73.03 ±20.60 | <.001 |

| Knowledge of oral manifestations from purging disordered eating behaviors | 72.63 ±15.34 | 88.18 ±15.85 | <.001 |

| Knowledge of treatment options for patients suspected of engaging in disordered eating behaviors | 85.93 ±17.63 | 95.45 ±08.74 | <.001 |

| Attitudes about role in secondary prevention | 13.29 ±03.35 | 17.49 ±03.08 | <.001 |

Tests are significant at p<.05.

Table 4 depicts changes in knowledge of eating disorders and secondary prevention from pre-intervention to post-intervention. On the whole, the participants were knowledgeable about eating disorders prior to the training. The major improvement was in the participants’ ability to distinguish among the major types of eating disorders.

Table 4.

Knowledge of eating disorders and secondary prevention of pilot evaluation participants (n=66)

| Variable | Pre-intervention % correct | Post-intervention % correct |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary prevention of eating disorders includes a) identifying the oral and physical findings of disordered eating behaviors, and b) providing patient-specific treatment and referral to reduce the severity of the disordered eating behaviors on oral and physical health. | 85.7% | 89.4% |

| Oral health care activities associated with secondary prevention of eating disorders include identifying the oral health issue, discussing etiology, and providing patient-specific treatment to reduce further damage to the tooth. | 93.5% | 92.4% |

| The main types of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorders not otherwise specified. | 20.8% | 90.9% |

| The intra- and extra-oral findings associated with disordered eating behaviors can be categorized as signs of malnutrition, dehydration, and vomiting. | 97.4% | 95.5% |

Consumer satisfaction variables are presented in Table 5. Generally speaking, participants found the web-based training pleasing and useful. The vast majority of participants either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that the program provided more information and resources about secondary prevention of eating disorders than is currently available, and the vast majority “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that the web-based training program was specifically tailored for dental professionals. Additionally, most participants “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that the training program was easy to navigate, understandable, easy to read, and easily accessible for future reference. Ninety-one percent of the participants also “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that if this training were made available, it would be accessed for information regarding secondary prevention of eating disorders. Finally, with regard to the overall usefulness and satisfaction of the training, 97 percent of the participants found the program “very useful” or “useful,” and 62.1 percent of the sample rated the program as “excellent.”

Table 5.

Web-based intervention consumer satisfaction

| Strongly Agree |

Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly isagree |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This web-based eating disorder training provides more information about secondary prevention of eating disorders than is currently available for dental professionals. | 48.5% | 40.9% | 9.1% | 1.5% | 0 |

| This web-based eating disorder training provides more resources about secondary prevention of eating disorders than are currently available to dental professionals. | 57.6% | 31.8% | 10.6% | 0 | 0 |

| This web-based eating disorder training provides information regarding secondary prevention of eating disorders that is tailored specifically for the dental professional. | 69.7% | 22.7% | 7.6% | 0 | 0 |

| This web-based eating disorder training is easy to navigate. | 71.2% | 21.2% | 6.1% | 1.5% | 0 |

| The information in this web-based eating disorder training is understandable. | 74.2% | 21.2% | 4.5% | 0 | 0 |

| The information in this web-based eating disorder training is easy to read. | 69.7% | 24.2% | 6.1% | 0 | 0 |

| This web-based eating disorder training can be easily accessible for future reference. | 56.2% | 25.8% | 6.1% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| If available, I would access this web-based eating disorder training for information regarding secondary prevention of eating disorders. | 71.2% | 21.2% | 3% | 3% | 2.5% |

| How useful was the program in teaching you secondary prevention of eating disorders? | Very Useful 72.7% |

Useful 24.3% |

Not Useful 3% |

||

| Overall, I would rate the web-based training program as: | Excellent 62.1%c |

Good 30.3% |

Fair 7.6% |

Poor 0 |

|

Note: Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding or skipped questions.

Discussion

Eating disorders are a significant public health problem that manifests itself in visible negative effects on oral tissues. Those effects provide the dental professional with a clinical opportunity for eating disorder-specific secondary prevention. However, secondary prevention and related clinical skills are not adequately addressed in most dental curricula or in continuing dental education. The lack of didactic and clinical instruction in secondary prevention of eating disorders occurs despite the recommendations of the American Dental Association’s “Future of Dentistry” report.51 This report states that the dental profession should “take the lead in convening all members of the health care community in developing a plan to incorporate appropriate oral and systemic health care concepts into the respective curricula.”

As such, there is a strong need for empirically evaluated training programs in eating disorders, and interactive web-based instructional programs can meet this need. The trend for e-curricula becoming widely adopted in oral health education lends further support for this program. Results of our pilot study demonstrated the efficacy of a web-based intervention comprised of clinical evaluation, patient approach, referral, and oral treatment to improve dental professionals’ capacity to deliver eating disorder-specific secondary prevention. Our pilot study demonstrated the short-term impact of the training module through significant changes in pre- to post-intervention in attitudes, beliefs, skills, and self-efficacy with regard to secondary prevention of eating disorders. The pilot study demonstrated the efficacy of the module among practicing oral health care providers and dental and dental hygiene students. The evaluation of consumer satisfaction and the perceived appropriateness of content, methods, and materials by the program participants lend further support to the acceptability of this program.

Potential intervention benefits emerged in all targeted outcome areas. First, program participants who received the intervention showed significant improvements in knowledge regarding behaviors associated with secondary prevention of eating disorders, oral manifestations from restrictive and purging disordered eating behaviors, and treatment options for patients suspected of engaging in disordered eating behaviors. Previous work by DeBate et al.27 found low levels of knowledge concerning oral cues, physical cues of anorexia nervosa, and physical cues of bulimia nervosa among oral health practitioners. With improved knowledge of oral and physical manifestations associated with eating disorders, the dental practitioner can provide a better assessment, as well as mechanisms for decreasing the potential for further damage to the teeth and oral cavity, thereby improving the patient’s quality of life.27

Within other targeted outcome areas, attitudes related to the secondary prevention of eating disorders also showed significant increases from pre- to post-intervention. Positive changes in attitudes among dental providers can improve clinical judgment, decision making, and values of professional behavior regarding the secondary prevention of eating disorders, and this can result in improvements in patient care.52 Furthermore, self-efficacy with reference to patient approach, patient communication, and behavior change strategies associated with eating disorder-specific secondary prevention also improved post-intervention. Positive changes in self-efficacy in this regard can potentially increase the likelihood of approaching a patient presenting signs of oral manifestations associated with disordered eating behaviors, offering patient-specific treatment, arranging for recall visits, making a referral treatment, initiating correspondence with the patient’s physician, and/or participating in case management.15,17

Our findings demonstrate that this training program provided more information and resources about the secondary prevention of eating disorders than what is currently available. The program was perceived as easy to read, access, navigate, and understand by the majority of the participants. These results suggest that this web-based intervention can potentially facilitate participant satisfaction and participant learning. Web-based learning is becoming increasingly popular, and it offers many advantages for dental and dental hygiene school faculty, students, and practitioners.53 Some of the benefits for faculty members include the following: access to material from multiple locations, controllable access only to students enrolled in the course, incorporation of multimedia material, a relatively low cost of program delivery, and, most importantly, a shift from instructor-centered to learner-centered education. Student and practitioner benefits of web-based learning include the following: increased accessibility related to both removal of geographic barriers and continuous access to course material at times convenient for the student, removal of restrictions regarding class sessions at times or places set by an institution, reduction in travel costs, and exploring the material at the student’s own pace.36,40 Overall, web-based learning can supplement and reinforce more traditional learning, and it has the potential to develop skills as well as knowledge.54

An important limitation of our pilot study is the lack of a control or comparison group. Although the program evaluation was able to assess immediate effects of knowledge and skill, this design did not allow a determination of whether changes observed were a direct function of the intervention. A second limitation involves the use of summative scores for many of our variables as sum scores do not describe where the changes occurred within the construct. Nonetheless, the current study served as a pilot study of the prototype web-based training program. A larger study with a control or comparison group is recommended to provide additional evidence to determine the effects of the web-based training program. Additionally, changes observed in knowledge were small, which suggests a need for enhancements in the training program and a more rigorous evaluation.

Whereas the current study has certain limitations, it nevertheless provides an interesting example of a prototype web-based training program on secondary prevention of eating disorders that demonstrated changes in attitudes regarding secondary prevention, knowledge of oral manifestations, knowledge of treatment options, and self-efficacy. The “Eating Disorders and Oral Health” training program addresses an important oral-systemic link for eating disorders and is one of the first web-based training programs to address the secondary prevention of eating disorders among oral health care providers. This web-based training program was well received by participants, and it could play a vital role in improving dental professionals’ capacity for delivery of eating disorder-specific secondary prevention. Ultimately, this program could reduce oral and medical complications and their treatment costs and improve patients’ quality of life. Future directions include targeting the training program for two separate educational audiences (e.g., practitioners and students) with different learning needs and methods. The revision of the training program will be followed by an experimental program to test program efficacy among the two educational audiences.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (1R43MH080474-01). We would like to thank the oral health faculty and students at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Kennedy King Community College, Santa Fe College, University of Florida, and Lane Community College for their input in the development and evaluation of this program.

Contributor Information

Rita D. DeBate, Associate Professor, Department of Community and Family Health, College of Public Health, University of South Florida

Herbert Severson, Senior Research Scientist, Deschutes Research, Inc.

Marissa L. Zwald, Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Community and Family Health, College of Public Health, University of South Florida

Tracy Shaw, Research Assistant, Deschutes Research, Inc.

Steve Christiansen, Media Director, Inter Vision Media

Anne Koerber, Associate Professor and Director, Division of Behavioral Sciences, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago

Scott Tomar, Professor and Chair, Department of Community Dentistry and Behavioral Science, College of Dentistry, University of Florida

Kelli McCormack Brown, Professor and Associate Dean of Academic Affairs, College of Health & Human Performance, University of Florida

Lisa A. Tedesco, Vice Provost for Academic Affairs–Graduate Studies, Dean of the Graduate School, and Professor, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tenore J. Challenges in eating disorders: past and present. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(3):367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoek H, vanHoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:383–396. doi: 10.1002/eat.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keski-Rahkonen A, Raevuori A, Hoek H. Epidemiology of eating disorders: an update. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, Zwaan MD, Steiger H, editors. Annual review of eating disorders: part 2, 2008. New York: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008. pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academy for Eating Disorders. [Accessed: June 6, 2008];Prevalence of eating disorders, 2008. At www.aedweb.org/eating_disorders/prevalence.cfm.

- 5.Thompson J, Smolak L. Introduction: body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth—the future is now. In: Thompson J, Smolak L, editors. Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: assessment, prevention, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell J. Medical complications of bulimia nervosa. In: Brownell K, Fairburn C, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simons-Morton B, Greene W, Gottlieb N, editors. Introduction to health education and health promotion. 2nd ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh C, Lemberg R. What we know about eating disorders: facts and statistics. In: Lemberg R, editor. Eating disorders: a reference sourcebook. Phoenix: Oryx Press; 1999. pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stege P, Visco-Dangler L, Rye L. Anorexia nervosa: review including oral and dental manifestations. J Am Dent Assoc. 1982;104:648–652. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1982.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts M, Li S. Oral findings in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a study of 47 cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:407–410. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1987.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hazelton L, Faine M. Diagnosis and dental management of eating disorder patients. Int J Prosthodont. 1996;9(1):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison J, George L, Cheatham J, Zinn J. Dental effects and management of bulimia nervosa. Gen Dent. 1985 Jan–Feb;:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atshuler B, Deshow P, Waller D, Hardy B. An investigation of the oral pathologies occurring in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1990;9(2):191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBate RD, Tedesco LA. Increasing dentists’ capacity for secondary prevention of eating disorders: identification of training, network, and professional contingencies. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(10):1066–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiGioacchino R, Keenan M, Sargent R. Assessment of dental practitioners in the secondary and tertiary prevention of eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2000;1:79–91. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(00)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeBate R, Tedesco L, Kerschbaum W. Oral health practitioners and secondary prevention of eating disorders: an application of the transtheoretical model. J Dent Hyg. 2005;79(4):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeBate R, Plichta S, Tedesco L, Kerschbaum W. Integration of oral health care and mental health services: dental hygienists’ readiness and capacity for secondary prevention of eating disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2006;33(1):113–125. doi: 10.1007/s11414-005-9003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tedesco LA. Issues in dental curriculum development and change. J Dent Educ. 1995;59(1):97–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassebaum DK, Hendrickson WD, Taft T, Haden NK. The dental curriculum at North American dental institutions in 2002–03: a survey of current structure, recent innovations, and planned changes. J Dent Educ. 2004;68(9):914–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendricson W, Cohen P. Oral health in the 21st century: implications for dental and medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1181–1206. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warnakulasuriya S. Effectiveness of tobacco counseling in the dental office. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(9):1079–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love C, Gerbert B, Caspers N, Bronstone A, Perry D, Bird W. Dentists’ attitudes and behaviors regarding domestic violence: the need for an effective response. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:85–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh N, Herzig K, Gansky S, Danley D, Gerbert B. Changing dentists’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about domestic violence through an interactive multimedia tutorial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(5):596–603. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerbert B, Moe K, Caspers N, Salber P, Feldman M, Herzig K, Bronstone A. Simplifying physicians’ response to domestic violence. West J Med. 2000;172(5):329–331. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolan T, McGorray S, Grinstead-Skigen C, Mecklenburg R. Tobacco control activities in U.S. dental practices. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1669–1679. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danley D, Gansky S, Show D, Gerbert B. Preparing dental students to recognize and respond to domestic violence. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:67–73. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeBate RD, Tedesco LA, Kerschbaum WE. Knowledge of oral and physical manifestations of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among dentists and dental hygienists. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(3):346–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida T, Milgrom P, Coldwell S. How do U.S. and Canadian dental schools teach interpersonal communication skills? J Dent Educ. 2002;66(11):1281–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeBate RD, Shuman D, Tedesco LA. Eating disorders in the oral health curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(5):655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field M, editor. An Institute of Medicine Report. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995. Dental education at the crossroads: challenges and change. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. Chicago: American Dental Association; 1998. Jan 1, [Google Scholar]

- 32.AADS Center for Educational Policy and Research. Leadership for the future: the dental school in the university. Washington, DC: American Association of Dental Schools; 1999. [now American Dental Education Association] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oral health in America: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haden NK, Andrieu SC, Chadwick DG, Chmar JE, Cole JR, George MC, et al. The dental education environment. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(12):1265–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walmsley A, White D, Eynon R, Somerfield L. The use of the Internet within a dental school. Eur J Dent Educ. 2003;7:27–33. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimes EB. Student perceptions of an online dental terminology course. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(1):100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimes EB. Use of distance education in dental hygiene programs. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(10):1136–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrews KG, Demps EL. Distance education in the U.S. and Canadian undergraduate dental curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(4):427–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendricson WD, Panagakos F, Eisenberg E, McDonald J, Guest G, Jones P, et al. Electronic curriculum implementation at North American dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2004;68(10):1041–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welbury R, Hobson R, Stephenson J, Jepson N. Evaluation of a computer-assisted learning programme on the oral-facial signs of child physical abuse (non-accidental injury) by general dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2001;190(12):668–670. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith TA, Raybould TP, Hardison JD. A distance learning program in advanced general dentistry. J Dent Educ. 1998;62(12):975–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porter S, Telford A, Chandler K, Furber S, Williams J, Price S, et al. Computer-assisted learning (CAL) of oral manifestations of HIV disease. Br Dent J. 1996;181(5):173–177. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson LA, Wohlgemuth B, Cameron CA, Caughman F, Koertge T, Barna J, Schulz J. Dental interactive simulations corporation (DISC): simulations for education, continuing education, and assessment. J Dent Educ. 1998;62(11):919–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson LA, Cunningham MA, Finkelstein MW, Hand JS. Geriatric patient simulations for dental hygiene. J Dent Educ. 1997;61(8):667–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Correa L, deCampos A, Souza S, Novelli M. Teaching oral surgery to undergraduate students: a pilot study using a web-based practical course. Eur J Dent Educ. 2003;7:111–115. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clancy J, Johnson L, Finkelstein M, Lilly G. Dental diagnosis and treatment (DDx & Tx): interactive videodisc patient simulations for dental education. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1990;33:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(90)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prochaska J, Redding C, Evers K. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: a guide for practitioners. New York: Harcourt Publishers Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenstock I, Streecher V, Becker M. Social learning theory and health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogers E, editor. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Dental Association. Health Policy Resources Center. Chicago: American Dental Association; Future of dentistry: executive summary. 2002

- 52.Kneebone R. Simulation in surgical training: educational issues and practical implications. Med Educ. 2003;37:267–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schleyer T. Digital dentistry in the computer age. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:1713–1720. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long A, Mercer P, Stephens C, Grigg P. The evaluation of three computer-assisted learning packages for general dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 1994;177:410–415. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]