Abstract

A novel population of cells that express typical immature neuronal markers including doublecortin (DCX+) has been recently identified throughout the adult cerebral cortex of relatively large mammals (guinea pig, rabbit, cat, monkey and human). These cells are more common in the associative relative to primary cortical areas and appear to develop into interneurons including type II nitrinergic neurons. Here we further describe these cells in the cerebral cortex and amygdala, in comparison with DCX+ cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, in three age groups of rhesus monkeys: young adult (12.3 ± 0.2 years, n = 3), mid-age (21.2 ± 1.9 years, n = 3) and aged (31.3 ± 1.8 years, n = 4). DCX+ cells with a heterogeneous morphology persisted in layers II/III primarily over the associative cortex and amygdala in all groups (including in two old animals with cerebral amyloid pathology), showing a parallel decline in cell density with age across regions. In contrast to the cortex and amygdala, DCX+ cells in the subgranular zone diminished in the mid-age and aged groups. DCX+ cortical cells might arrange as long tangential migratory chains in the mid-age and aged animals, with apparently distorted cell clusters seen in the aged group. Cortical DCX+ cells colocalized commonly with polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule and partially with neuron-specific nuclear protein and γ-aminobutyric acid, suggesting a potential differentiation of these cells into interneuron phenotype. These data suggest a life-long role for immature interneuron-like cells in the associative cerebral cortex and amygdala in nonhuman primates.

Keywords: neuroplasticity, interneurons, neurogenesis, aging, neuropsychiatric disorders

Introduction

One of the most fundamental features of the brain is its plasticity, a constant interplay between neural structure, function and experience. The scope and complexity of neuroplasticity appear to increase during evolution in parallel with the enlargement of brain through encephalization, corticalization and gyrification (Finlay and Darlington, 1995). Thus, plasticity is likely the foundation of the so-called “higher brain functions” (e.g., learning, memory, decision-making, or intelligence) that are mostly sophisticated in humans (Azmitia, 2007). In general, the associative cortical areas together with the amygdala and hippocampal formation, which are greatly expanded during late mammalian evolution, are the anatomic niches for many high-level cognitive functions (Krubitzer, 2009; Pierani and Wassef, 2009). Greater neuroplasticity is likely inherent with higher vulnerability to environmental and internal insults. In line with this notion, cellular deficits and structural changes in the associative cortical and limbic areas are associated with some neurological or neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., mode disorders, schizophrenia, epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease) in the adolescent, adult and aged human populations (Arendt, 2005; Di Cristo, 2007; Brambilla et al., 2008; Pavuluri and Passarotti, 2008; Siebzehnrubl and Blumcke, 2008).

Neuroplasticity is a complex process involving structural modulations at synaptic, neuronal and circuitry/pathway levels (Bruel-Jungerman et al., 2007). Of particular interest, formation of new neurons in the adult brain has been recently recognized as a key substrate for neuroplasticity and cognition (Lledo et al., 2006; Aimone et al., 2009). For instance, adult neurogenesis in the forebrain subventricular and subgranular zones (SVZ, SGZ) appears to be essential for olfaction and hippocampus-dependent learning and memory in rodents (Shors et al., 2001; Magavi et al., 2005; Hernández-Rabaza et al., 2009).

Newly-generated neurons in the SVZ and SGZ express a set of immature neuronal markers including doublecortin (DCX+) and polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM, Magavi et al., 2000; Gritti et al., 2002; Couillard-Despres et al., 2005). Concurrent with morphological development, these new neurons differentiate through a correlated process of downregulation of the above-mentioned immature markers and upregulation of common (e.g., neuron-specific nuclear protein, NeuN) or specific terminal neuronal markers, thus eventually become fully integrated into functional neuronal circuitries in the adult brain (Brown et al., 2003).

Besides the SVZ/SGZ, a novel population of DCX+ cells coexpressing other immature neuronal markers has been recently characterized in the cerebral cortex of guinea pigs, rabbits, cats and primates from young to mid-age adulthood (Liu et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2009; Luzzati et al., 2009). These DCX+ cells are more common in the associative relative to primary cortical areas, and appear to develop into interneuron subgroups in guinea pigs and cats (Xiong et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2009). We show here in rhesus monkeys that DCX+ cells persist into advanced ages in the associative frontal and temporal lobe cortex and amygdala, even in very old animals with substantial cerebral amyloid pathology. In contrast, DCX+ cells are rare in the hippocampus by mid-age. DCX+ cells in the monkey cortex also appear to develop into GABAergic phenotype. These data point to a life-long role for novel immature interneuron-like cells in nonhuman primate cerebral structures that are crucial for cognitive functions.

Materials and Methods

Animal and tissue preparation

Brain sections from 10 male (n = 6) and female (n = 4) normal rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were used in the present study (Chu and Kordower, 2007). The animals were divided into young adult (12.1, 12.4 and 12.5 years, mean = 21.2 ± 1.9 years), mid-age (19, 22 and 22.5 years, mean = 12.3 ± 0.2 years), and aged (30, 30.3, 31 and 34 years, mean = 31.3 ± 1.8 years) groups. According to the 1:3 monkey verse human age converting ratio, the mean ages of these groups were approximately 37, 64 and 94 years old relative to human age. DCX immunolabeling pattern from the young adult group has been described in our recent report (Cai et al., 2009). Therefore, we only include densitometric data from this group in the current study. All monkeys were housed individually on a 12-h on/12-h off lighting schedule with ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were sedated with Ketamine (20 mg/kg, i.m.) and then were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (25 mg/kg, i.v.). Prior to perfusion, monkeys were injected with 1 ml of heparin (20,000 IU) into the left ventricle of the heart. Animals were then perfused with normal saline followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were then removed and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer at 4°C. Serial sections throughout the cerebral hemisphere were cut frozen (40 um) at the frontal plane on a sliding microtome and stored at −20°C in cryoprotectant before they were analyzed in the present study.

Animal use was in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rush University.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were first treated with 1% H2O2 in PBS for 30 min, and pre-incubated in 5% normal rabbit serum in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with goat anti-DCX antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8066, 1:2000) overnight at 4°C. Sections were further reacted with biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG at 1:400 for 2 h, and subsequently with ABC reagents (1:400) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h. Immunoreaction product was visualized using 0.003% hydrogen peroxide and 0.05% diaminobenzidine. Three 10-min washes with PBS were used between incubations. Sections were mounted on slides, allowed to air-dry, and then coverslipped. Some immunostained sections were lightly counterstained with cresyl violet to verify the laminar distribution of the labeled cells. Some sections from the aged monkey group were stained for amyloid deposition using mouse anti-amyloid peptide amino acids 1–16, clone 6E10 (Signet, #39320, 1:4000).

For double immunofluorescence, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 5% normal donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 and goat anti-DCX (1:2000) together with one of the following antibodies: mouse anti-PSA-NCAM (Chemicon, MAB5324, 1:2000), mouse anti-NeuN (Chemicon, MAB377, 1:4000), mouse anti-GABA (Sigma-Aldrich, A0310, 1:10000) and 6E10. Sections were then reacted for 2 h with Alexa-Fluor® 488 conjugated donkey anti-goat and Alexa-Fluor® 594 conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgGs (1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sections were finally counter-stained with bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33342, 1:50000), washed and coverslipped with anti-fading medium (Vector Laboratories).

Imaging, densitometry and data analysis

Peroxidase-DAB stained sections were examined using an Olympus (BX60) fluorescent microscope equipped with a digital camera and imaging system (Optronics, Goleta, CA, USA). In each brain five equally-spaced sections (1 mm apart) around the middle levels of the amygdala were used to quantify DCX+ cells in the amygdala, entorhinal cortex (Ent) and inferior temporal gyrus (ITG). Similarly, five sections (1 mm apart) across the mid-hippocampus and anterior to the genu of corpus callosum were used to count DCX+ cells in the dentate gyrus and the medial orbital gyrus (MOG), respectively. Because the labeled somata were distributed as cellular bands in these analyzed forebrain regions, the lengths of overlying white matter border, cortical pial surface and granular cell layer (GCL) were used as internal references to calculate the relative abundance of cells in the amygdala, various cortical areas and dentate gyrus, respectively. Cell numbers were counted over montages of images taken at 10X using Image-J software as descried in detail in Xiong et al. (2008). For the purpose of cross-age and cross-region comparisons, averaged relative densities of DCX+ cells in a given brain region were normalized to the mean density of the same region from the young adult group. Mean densities were analyzed statistically using one- and two-way ANOVA, together with Bonferroni posttests between multiple pairs of mean values, whenever applicable (Prism GraphPad 4.1, San Diego, CA, USA). The minimal significance level was set at p < 0.05.

A Zeiss fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager, equipped with Apo Tom analysis system) was used to study colocalization of immunolabelings. Immunofluorescence emitted from the top ∼4 μ of the tissue was captured. Image overlapping was done with the Optronics imaging software, and illustrations were prepared with Photoshop 7.1.

Results

Overall distribution of DCX+ cells in the monkey forebrain

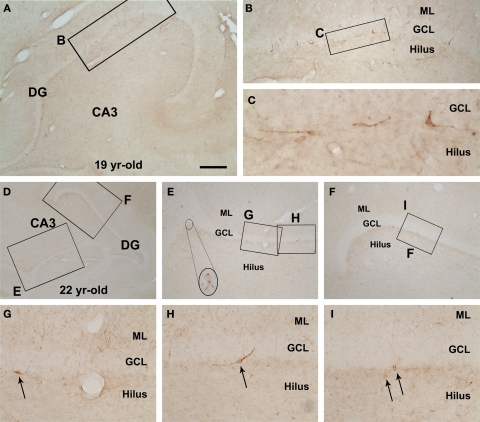

DCX+ cells in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus were considerably common in the young adult group (as shown in Figure 8E in Cai et al., 2009). In the mid-age group a few labeled cells occurred in the DG deep to the GCL (Figure 1). These immature granule cells were small and bipolar, had limited dendritic branches, and were mostly oriented with the long somal diameter oblique or parallel to the GCL. In contrast, DCX+ granule cells were very rare or essentially absent in the dentate gyrus in all aged monkeys examined in the present study (images not shown).

Figure 1.

Rare doublecortin-immunoreactive (DBX+) cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of rhesus monkeys aged around 20 years old (mid-age group). Shown are low magnification views of the DG and CA3 sector in a 19-year-old (A,B) and a 22-year-old (D–I) animals, with enlarged areas depicting examples of apparently dysmorphic DCX+ cells at the border between the granular cell layer (GCL) and the hilus. DCX+ cells are small, mostly bipolar, and often arranged with their long somal diameter parallel to the GCL. Some cells (arrows in G–I) have a few dendritic processes extending across the GCL into the molecular layer (ML). Scale bar = 1 mm in (A) applying to (E,F), equivalent to 2 mm for (D), 100 μm for (B) and 50 μm for (G–I), and 25 μm for (C).

Two previous studies demonstrated putative immature neurons in the amygdala of young adult nonhuman primates (Bernier et al., 2002; Tonchev et al., 2003). We noted DCX labeling in this population of amygdalar cells in all age groups of rhesus monkeys. These DCX+ cells were located along the junction of the amygdale to the whiter matter of the Ent, appearing as a cellular band (Figures 2A,B). The ventral end of this amygdalar band appeared to somewhat continue with the DCX+ cell band in layers II/III of the Ent (Figures 2C,D and 3A–C).

Figure 2.

Distribution of DCX+ cells in the temporal lobe cortical areas surrounding the amygdala (A–K), in the insular (Ins) and secondary somatosensory (S2) cortex (L), and in the ventral prefrontal cortex including the medial and lateral orbital gyri (MOG, LOG) (M–O) in a 22-year-old rhesus monkey. Framed areas in lower magnification panels are enlarged sequentially as indicated. DCX+ cells in the amygdala (Amyg) are located near the white matter deep to the entorhinal cortex (Ent) as a cellular band, which continues into the adjoining Ent and further dorsally into the inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) around the border of layers I and II (A–C). Labeled cells are mostly small and bipolar, often arrange as clusters and chains with cells seemingly migrate outside-in intracortically (C,F). However, in the ITG a large number of cells are associated with tangentially arranged migratory chains that can extend very long (D,G–K). Some of these chains appear to extend from layer I and then enter the cortical plate, with cells dispatching or being dispersed around the end of the chains (D,J,K, green arrows). Note that labeled cells are also fairly common in the MOG and LOG (M,N), but fewer in the Ins cortex and S2 (L). A few relatively large cells with reduced DCX reactivity are present in layers II/III (indicated with black arrows in K,N,O). rf, rhinal fissure; LF, lateral fissure. Arab numbers indicate cortical layers. Scale bar = 3 mm in (A) applying to (E,F), equivalent to 1 mm for (B,C), 500 μm for (D), 100 μm for (G,H,L–N) and 50 μm for (E,F,I–K,O).

Figure 3.

Presence of DCX+ cells (A–H) in the amygdala (A,B) and the cortex (C–H) of a 34-year-old monkey with cerebral amyloid plaques (I,J), as indicated. A decreased amount of DCX labeling is noticeable as compared to Figure 2 in corresponding cerebral areas. Labeled profiles in layers I–III, especially their clusters, appear disorganized (C–F). An expanded bizarre-looking migratory cell cluster is illustrated in (D). Long tangential and oblique migratory chains occur around layers I and II (E,F). The distribution of amyloid plaques around the hippocampal formation and temporal lobe structures is shown with 6E10 immunolabeling with Nissl counterstain (I,J). Some plaques occur in layers II and III wherein DCX+ cells exist (J). Sub, subiculum; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus, FuG, fusiform gyrus; opts, occipitotemporal sulcus. Other abbreviations are the same as in Figure 2. Scale bar = 250 μm in (A), equivalent to 500 μm for (I), 150 μm for (C,G), 100 μm for (J) and 50 μm for (B,D–F,H).

DCX+ cortical cells in the young adult monkeys were present virtually across the cerebral hemisphere, and appeared as a cellular band in layers II/III with an overall ventrodorsal high to low gradient at a given frontal plane (also see Figure 8 in Cai et al., 2009). For instance, in the temporal lobe sections a distinct cellular band continued from the Ent, across the temporal gyri, and to the insular (Ins) cortex. In the mid-age animals, the cellular band was seen over the Ent and ITG, but became less evident in the medial temporal gyrus (MTG) and more dorsally-located cortical areas (Figure 2). In the aged monkeys, this cellular band became largely restricted to the junction of the Ent and ITG, although labeled cells were still seen in small groups or clusters in the MTG, STG and Ins cortex (Figure 3).

DCX+ cells were occasionally detected in the primary motor and sensory cortical areas as isolated cells or small groups of cells in layer II, without a consistent or noticeable region-specific pattern in the mid-age monkeys. However, labeled perikarya were fairly common in the dorsal lateral and ventral prefrontal cortical areas (Figures 2M–O and 3G).

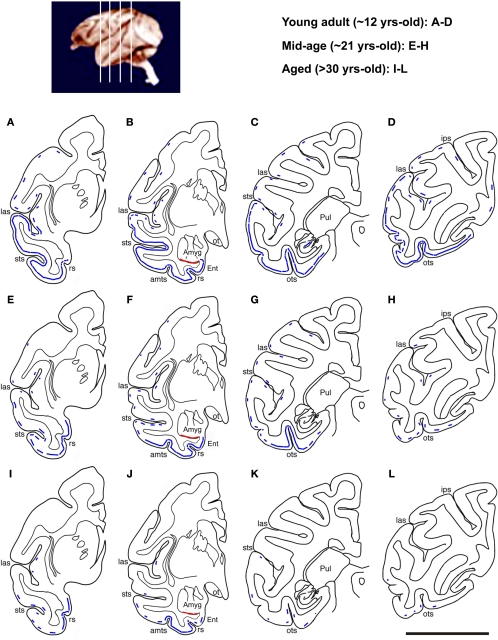

We illustrated the above-mentioned age-related changes in relative abundance of DCX+ cells over the temporoparietal cortical areas using hemispheric maps created based on visual scoring of labeled profiles in multiple sections in each brain (Figure 4). The low temporal lobe regions exhibited most abundant DCX labeling in each age group. Also, considerable amount of labeled profiles persisted in these regions to the aged group (Figure 4I–L). Thus, more detailed quantitative and morphological studies of DCX+ cells were carried out in these regions (the amygdala, Ent and ITG), together with the MOG of the prefrontal cortex and DG (see below).

Figure 4.

Schematic drawings illustrating an overview of age-related change in DCX+ cell distribution in the temporoparietal cortical areas at four representative anterioposterior frontal levels as indicated in the top-left map. In the young adult group (A–D), DCX+ cortical cells occur in layers II/III as a continuous cellular band (blue line) extending ventrally from the entorhinal cortex (Ent) to laterally all of the temporal neocortical areas. There follows a parallel decline in the abundance of labeled cells along this band with age (E–L). Thus, the cellular band “retracts” dorsoventrally to become impressive only in the ventral temporal areas, especially around the joining portion between the Ent and inferior temporal gyrus, in the aged group (I–L). A small number of labeled cells exists in the insular and parietal cortical areas in young and mid-age animals (broken line), and they disappears in the aged animals. A cellular band at the border of the amygdala and the cortical white matter is seen in all groups (red line): sts, superior temporal sulcus; amts, anteriomedial temporal sulcus; ots, occipitotemporal sulcus; Pul, putamen; ips, interparietal sulcus; ot, optic tract; rs, rhinal sulcus. Scale bar = 1 cm.

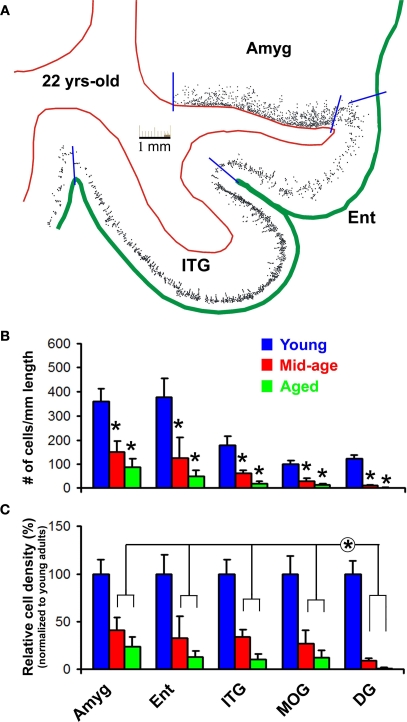

Decline of DCX+ cells with age in monkey forebrain regions

Overall, the numeric densities of DCX+ cells were reduced significantly in all analyzed forebrain areas in the mid-age and aged relative to young adult groups (Figure 5). DCX+ cells in the amygdala dropped to 41 ± 13% (mean ± SD, same below) in the mid-age and 24 ± 10% in the aged relative to the young adult (100 ± 15%) groups (p = 0.003, F = 33, df = 2, one-way ANOVA). In the Ent and ITG, labeled cells reduced to 32 ± 22 and 34 ± 8% in the mid-age and 13 ± 8 and 11 ± 6% in the aged groups compared to the young adults (100 ± 20 and 100 ± 15%) (p < 0.0001, F = 41 and 72, df = 2, one-way ANOVA). DCX+ cells in the MOG reduced to 27 ± 13% in the mid-age and 13 ± 7% in the aged relative to the young adult (100 ± 19%) groups (p < 0.0001, F = 45, df = 2, one-way ANOVA). DCX+ cell density in the DG was 9 ± 3 and 1.2 ± 1% in the mid-age and the aged compared to the young adult (100 ± 14%) groups (p < 0.0001, F = 170, df = 2, one-way ANOVA). There existed a significant difference in the extent of decline of normalized mean densities across the analyzed regions in both the mid-age and aged groups (p < 0.0005, F = 12, df = 3, 20, two-way ANOVA). Bonferroni posttests indicated that this region-related difference was due to a more dramatic reduction of DCX+ cells in the DG relative to the amygdala and all cortical areas (p < 0.05 to p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Age-related decline of DCX+ cells in the monkey forebrain based on densitometry over representative areas including the amygdala (Amyg), entorhinal cortex (Ent), inferior temporal gyrus (ITG), medial orbital gyrus (MOG) and dentate gyrus (DG). (A) shows an example of cell map reproduced from montaged 10× microscopic images over a mid-amygdala section from the 22-year-old animal. Red lines mark the borders between the white matter and gray matter of the cortex or between the amygdala and cortical white matter, and green line defines the pial surface. Blue bars indicate the locations used to divide the cortical areas, and to define the length of corresponding cellular bands in the amygdala (along the white matter border) and cortex (along the pial surface). Bar graph (B) shows cell densities (mean ± SD) in different areas in the three age groups. Bar graph (C) represents averaged densities normalized to the mean densities of corresponding regions in the young adult group (i.e., defined as 100%). Statistic analyses indicate a significant (*) reduction of DCX+ cells with age in all analyzed areas (B), and a significantly greater decline of cells in the DG relative to the amygdala and cortical areas (C).

Chain migration and clusterization of DCX+ cells in mid-age and aged monkey cortex

We recently described chain migratory structures of DCX+ cells in the young adult cat and monkey cortex arranged largely perpendicular to the pial surface and with labeled cells seemingly migrating from layer II to deeper layers (Cai et al., 2009). In the current study somewhat different intracortical migratory pattern and clusterization of the labeled cells were noticed in mid-age and aged monkeys relative to young adults. Thus, besides the inwardly arranged chains (Figure 2F), considerably long migratory chains of DCX+ cells and processes occurred tangentially around the border of layers I and II in mid-age and aged monkeys, mostly prominent in the ITG. Closer examination indicated that some of these chains appeared to derive from layer I then invaded the cortical plate (Figures 2G-J, 3E,F and 6D–H). DCX+ cells appeared to migrate along these chains, then leave en route or radially at the end of a given chain to disperse in layers II/III (Figures 2J,K, 3D–F and 6D,H). Of note, in the aged group irregular or bizarre-shaped cell aggregations or clusters occurred around the border of layers I and II. These clusters might be in small to fairly large sizes (up to 0.5 mm), with some associated cells appearing to migrate away “aberrantly” – toward the cortical plate or even the pia (Figures 3C,D).

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescent images from the 22-year-old monkey illustrating colocalization of polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) and neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) in DCX+ cells (including bisbenzimide nuclear stain in D and H) in the prefrontal (MOG, A–C) and temporal lobe cortex (D–K). PSA-NCAM and DCX are colocalized in individual cells as well as cells arranged in chains perpendicular (A–C) or tangential (D) to the cortical surface. NeuN is detectable in a small number of DCX+ cells with relatively larger size and lighter DCX reactivity (arrows in I–J, and enlarged circles in G) than those lack colocalization (arrowheads in I–K). Note DCX+ tracts and migratory chains in layers I (E–G) and II (H). Abbreviations are the same as in Figure 2. Scale bar = 100 μm in (A–C), equivalent to 200 μm for (E–G), 50 μm for (D,I–K).

Compared to the cortex, DCX+ cells in the amygdala did not exhibit obvious chain-like arrangement and clusterization, although the density of labeled cells decreased sharply from the white matter border toward the center of the amygdala (Figures 2B,E and 3A,B).

It should be mentioned that the 34-year-old animal in the aged group exhibited considerable amyloid plaque pathology in the hippocampus and across the cerebral cortex (Figures 3I,J and 7L–O). The 30-year-old animal also showed amyloid deposition to a lesser extent in these same brain areas, whereas the forebrains of the remaining two aged animals were essentially plaque-free (data not shown).

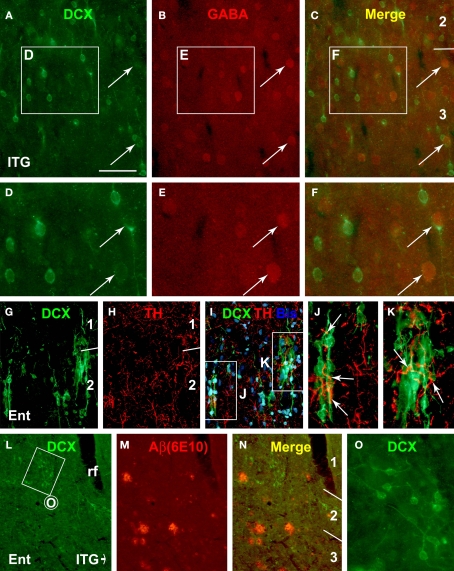

Figure 7.

Representative immunofluorescent images from the 19-year-old (A–K) and the 34-year-old (L–O) monkeys depicting double labeling of DCX with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and β-amyloid peptide (Aβ, 6E10 staining) in the cortical areas as indicated. GABA immunoreactivity is detectable in a small subset of relatively large DCX+ cells (arrows, A–F). TH immunoreactive axonal plexuses (arrows) occur around DCX+ cells and chains in layer II (G–K). DCX+ cells do not appear to preferentially occur around amyloid plaques, nor do they apparently disappear from areas with plaques (L–N). Scale bar = 50 μm in (A–C) applying to (J,K), equivalent to 100 μm for (G–I,L–N), and 25 μm for (D–F,O).

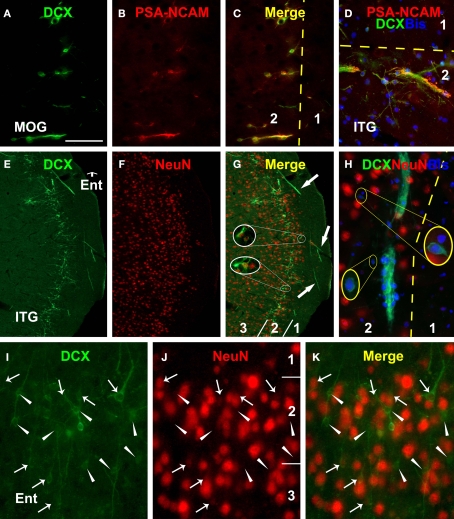

Immunofluorescent characterization of DCX+ cells in monkey cerebral cortex

In freshly-processed cat cerebral cortex, NeuN and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are co-expressed in relatively large mature-looking cells with peak and with reduced levels of DCX expression. In contrast, glutamic acid decarboxylase, calbindin, parvalbumin, neuronal nitric oxide synthase are only detectable in mature-looking cells with attenuated DCX expression (Cai et al., 2009). In the monkey materials we examined the latter subgroup of DCX+ cells occurred infrequently (as shown in Figures 2K,O), potentially due to the long time tissue storage (3–4 years) that might have caused some loss of DCX antigenicity. Therefore, double immunofluorescence was carried out only for potential colocalization of DCX with PSA-NCAM, NeuN and GABA to evaluate the presumed immature and developing neuronal phenotype as well as GABAergic fate of the DCX+ cells.

There existed a virtually complete colocalization of DCX and PSA-NCAM among individually-distributed small or larger cells, as well as among small cells associated with long migratory chains in all monkeys (Figures 6A–D). As expected, we also detected colocalization of NeuN or GABA in a small number of cortical DCX+ cells with relatively large somal size and low levels of DCX reactivity (Figures 6E–K and 7A–F).

Certain antidepressants that modulate monoamine neurotransmission may influence the expression of DCX or PSA-NCAM in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Sairanen et al., 2007; Varea et al., 2007; Perera et al., 2008). Also, the superficial cortical layers including layer I are innervated by monoaminergic terminals from subcortical structures, including catecholaminergic projection neurons (Campbell et al., 1987; Lewis et al., 1987). Therefore, it was of interest to explore whether DCX+ cells in the primate cerebral cortex might be in a position to be influenced by catecholaminergic inputs. Indeed, DCX+ cells and processes around the border of layers I/II were found to be surrounded by or in close proximity to axon terminals immunolabeled for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). Moreover, some TH+ axonal plexuses appeared to extend alongside or coil around the chain-like migratory elements of DCX+ cells oriented inwardly or tangentially in the superficial cortical layers (Figures 7G–K).

Following an initial check for extracellular amyloid deposition in all aged animals, we carried out DCX and 6E10 double immunofluorescence in the cortex from two aged monkeys with cerebral plaques in an effort to explore if there was direct and apparent impact between DCX+ cells and plaque pathology. DCX+ cells were not found to preferentially occur around 6E10 labeled amyloid plaques. Also, in layers II and III the distribution or number of DCX+ cells did not appear to be apparently altered around areas with plaques relative to plaque-free areas in the sections we examined (Figures 7L–O).

Discussion

DCX+ cortical cells in comparison with adult-born dentate granular cells

Recent studies by our group and others have gathered substantial information on cortical DCX+ cells or alike in various mammalian species, which now allows a comparison between these novel cortical cells and the conventional adult-born neuronal populations in SVZ and SGZ (Gómez-Climent et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2008; Luzzati et al., 2009). Taking the newly-generated SGZ immature neuronal population as an example, we attempted to update relevant features of cortical and hippocampal DCX+ cells (see Table 1). Similar properties of these two populations include that both groups: (1) express the very same set of immature neuronal markers including DCX, PSA-NCAM, neuron-specific β-tubulin-III (TuJ1) and Hu; (2) exhibit a diverse variation in somal size and shape, nuclear appearance in bisbenzimide stain and complexity of neuritic processes, all suggesting cell growth and morphological maturation; (3) display a pattern of transient expression of immature neuronal markers that overlap partially with the emergence of mature neuronal markers but correlate with morphological development (Brown et al., 2003; Cai et al., 2009); (4) may arrange as tightly-apposed cell clusters and/or as migratory chains, suggestive of certain neuroblast-like behavior or property (Gritti et al., 2002; Seki et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2009); (5) reduce in number with age in all studied mammals; (6) might be modulated by some antidepressants at least according to rodent studies (Sairanen et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Comparison of hippocampal with cortical DCX+ cells.

| Features or observations | SGZ | Layers II/III |

|---|---|---|

| Transient expression of immature neuronal markers1 | Yes | Yes |

| Partial co-expression of mature neuronal markers2 | Yes | Yes |

| Heterogeneous developing neuronal | Yes | Yes morphology |

| Response to antidepressants | Yes | Likely |

| Time of cell presence during postnatal life | To mid-age | Life long |

| Migration | Across the GCL | Inwardly |

| Definitive or putative destiny | Granule cells | Interneurons |

| BrdU incorporation | Yes | Inconsistent |

| Retrovirus incorporation | Yes | No report |

1DCX, PSA-NCAM, neuron-specific β-tubulin-III (TuJ1) and Hu.

2NeuN and some terminal phenotype markers of interneurons.

However, to date the most confusing (yet compelling) issue regarding cortical DCX+ cells is whether they are generated prenatally, postnatally or even throughout adult life. Several groups report a low rate of BrdU incorporation into DCX+ cells in the piriform or temporal lobe cortex in small laboratory rodents and primates (Bernier et al., 2002; Tonchev et al., 2003; Pekcec et al., 2006; Shapiro et al., 2007, 2008). In contrast, others suggest that this population of cortical cells is produced prenatally (Gómez-Climent et al., 2008; Luzzati et al., 2009). With this regard, the current finding of persistent occurrence of DCX+ cells in the cortex and amygdala virtually to the end of life in nonhuman primates is very puzzling. For instance, it appears difficult to explain how prenatally-born neuronal precursors form seemingly more extended migratory chains and overtly expanded or bizarre-looking cell clusters in aged rather than younger adult animals.

Potential effect of aging on DCX+ cell migration in the cortex

As aforementioned, the arrangement of cortical DCX+ cells as extended tangential migratory chains and expanded/distorted migratory apparatus in layers I/II in mid-age and aged primates is of interest. This pattern seems to fit with our earlier speculation that the lamination and clusterization of DCX+ cells at this location might be somehow related to layer I or the marginal zone, which is an embryonic and potentially postnatal neurogenic site (Marin-Padilla, 1978; Letinic et al., 2002; Costa et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2008). As shown earlier (Cai et al., 2009), cortical DCX+ cells in young adult cats and monkeys appear to mostly migrate from layer II to deeper layers. Thus, the increased tendency of tangential cell migration in older animals might implicate certain type of age-related alteration in the distribution of cortical DCX+ cells.

Previous studies suggest that the radial migration of newly-generated hippocampal neurons might be impaired in aged rodents, dogs and monkeys (Siwak-Tapp et al., 2007; Ribak and Shapiro, 2008; Hwang et al., 2009). Thus, DCX+ cells in aged dentate gyrus tend to retain at the SGZ with their long somal diameter parallel to the GCL. In contract, dentate DCX+ cells in younger animals migrate across the GCL during their morphological maturation (Shapiro et al., 2005). Thus, the extended tangential migration and distorted clusterization of DCX+ cells around layers I and II in aged monkeys could potentially reflect certain deficit of migration or dispersion/descending of these cells in the cortex.

Functional consideration for life-long presence of DCX+ cells in primate cerebrum

Little is currently known about the functional implication for a life-long presence of putative immature and developing neurons in mammalian associative cerebral cortex and amygdala. Giving their potential GABAergic fate, it seems plausible that these novel cells might be involved in interneuron plasticity under physiological conditions, and perhaps interneuron dysfunction under certain disease conditions as exampled below.

Recent studies suggest that interneuron deficits might relate to the etiology of certain neuropsychiatric diseases. It appears that bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia are associated with reduced GABAergic interneurons and/or altered inhibitory neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex (Benes et al., 2000; Beasley et al., 2002; Lewis et al., 2004, 2008; Di Cristo, 2007; Rajkowska et al., 2007; Sanacora and Saricicek, 2007; Lodge et al., 2009). We observe a substantial population of DCX+ cells in the prefrontal cortex of young adult guinea pigs, cats and monkeys, and as shown in the present study, these cells are likely to be in close anatomic relationship with dopaminergic and/or norepinephrinergic projections. Thus, whether the differentiation and maturation of DCX+ cortical cells into putative interneuron subgroups may be impaired under certain conditions and be modulated by antidepressant or anti-psychiatric drugs are of potential medical relevance.

Structural and functional changes in the interneuron systems may relate to the pathophysiology of temporal lobe epilepsy (Ben-Ari, 2006). Two late studies show altered DCX expression in the temporal cortex from epileptic human subjects relative to controls (Liu et al., 2008; Srikandarajah et al., 2009). Other studies suggest changes in GABAergic neurons and inhibitory neuronal circuitry in chronic epileptic human temporal cortex and amygdala (Arellano et al., 2004; Yilmazer-Hanke et al., 2007; Knopp et al., 2008; González-Martínez et al., 2009). Thus, the relevance of cortical DCX+ cells to seizure or epilepsy-related aberrant interneuron plasticity deserves further investigation.

A role for impaired neurogenesis in cognitive decline during aging and in Alzheimer's disease has been lately proposed according to studies of adult-born neuronal populations in the hippocampus and SVZ (Galvan and Bredesen, 2007; Jessberger and Gage, 2008). We observe diminished DCX+ subgranular cells in mid-age and aged monkeys, consistent with other reports that hippocampal neurogenesis is dramatically reduced around mid-age in most mammals (Simon et al., 2005; Leuner et al., 2007; Siwak-Tapp et al., 2007; Hattiangady et al., 2008; Ribak and Shapiro, 2008; Hwang et al., 2009). Our current study however reveals a remarkably intriguing fact that putative immature cortical neurons persist into very old age in non-human primates, in sharp contrast to a great loss of hippocampal neurogenesis well before the onset of senescence. Thus, there exists an extended time window for a potential involvement of cortical and amygdalar DCX+ cells in aging-related changes in neuronal plasticity and perhaps cognitive decline in nonhuman primates. Of particular concern regarding this finding includes whether DCX+ cortical and amygdalar neurons may be altered in Alzheimer's disease. The present study could not establish a clear inductive or destructive effect of amyloid plaques on DCX+ cells in aged monkey cerebrum. Obviously, we could not rule out such a possibility, giving the limited sample size available for this study.

In summary, the present study demonstrates a population of putative developing neurons with a presumable GABAergic fate that persists into advanced age in rhesus monkeys, especially in the associative cerebral cortical areas and amygdala. This finding is in contrast to a great, if not complete, loss of DCX+ cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus in the aged animals. The data implicate a potential life-long role for novel immature neurons in cognition-related cerebral structures, as well as a protracted time window for possible interaction or modulation between these cells and aging-related neurobiological or neuropathological factors in primates during their late life.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/neuroanatomy/paper/10.3389/neuro.05/017.2009/

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aimone J. B., Wiles J., Gage F. H. (2009). Computational influence of adult neurogenesis on memory encoding. Neuron 61, 187–202 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano J. I., Muñoz A., Ballesteros-Yáñez I., Sola R. G., DeFelipe J. (2004). Histopathology and reorganization of chandelier cells in the human epileptic sclerotic hippocampus. Brain 127, 45–64 10.1093/brain/awh004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T. (2005). Alzheimer's disease as a disorder of dynamic brain self-organization. Prog. Brain Res. 147, 355–378 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia E. C. (2007). Cajal and brain plasticity: insights relevant to emerging concepts of mind. Brain Res. Rev. 55, 395–405 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley C. L., Zhang Z. J., Patten I., Reynolds G. P. (2002). Selective deficits in prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons in schizophrenia defined by the presence of calcium-binding proteins. Biol. Psychiatry 52, 708–715 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01360-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. (2006). Seizures beget seizures: the quest for GABA as a key player. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 18, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes F. M., Todtenkopf M. S., Logiotatos P., Williams M. (2000). Glutamate decarboxylase(65)-immunoreactive terminals in cingulate and prefrontal cortices of schizophrenic and bipolar brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 20, 259–269 10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier P. J., Bedard A., Vinet J., Levesque M., Parent A. (2002). Newly generated neurons in the amygdala and adjoining cortex of adult primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11464–11469 10.1073/pnas.172403999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P., Hatch J. P., Soares J. C. (2008). Limbic changes identified by imaging in bipolar patients. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 10, 505–509 10.1007/s11920-008-0080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. P., Couillard-Després S., Cooper-Kuhn C. M., Winkler J., Aigner L., Kuhn H. G. (2003). Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 467, 1–10 10.1002/cne.10874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel-Jungerman E., Davis S., Laroche S. (2007). Brain plasticity mechanisms and memory: a party of four. Neuroscientist 13, 492–505 10.1177/1073858407302725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Xiong K., Chu Y., Luo D. W., Luo X. G., Yuan X. Y., Struble R. G., Clough R. W., Spencer D. D., Williamson A., Kordower J. H., Patrylo P. R., Yan X. X. (2009). Doublecortin expression in adult cat and primate cerebral cortex relates to immature neurons that develop into GABAergic subgroups. Exp. Neurol. 216, 342–356 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. J., Lewis D. A., Foote S. L., Morrison J. H. (1987). Distribution of choline acetyltransferase-, serotonin-, dopamine-beta-hydroxylase-, tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers in monkey primary auditory cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 261, 209–220 10.1002/cne.902610204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y., Kordower J. H. (2007). Age-associated increases of alpha-synuclein in monkeys and humans are associated with nigrostriatal dopamine depletion: is this the target for Parkinson's disease? Neurobiol. Dis. 25, 134–149 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. R., Kessaris N., Richardson W. D., Götz M., Hedin-Pereira C. (2007). The marginal zone/layer I as a novel niche for neurogenesis and gliogenesis in developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 27, 11376–11388 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2418-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillard-Despres S., Winner B., Schaubeck S., Aigner R., Vroemen M., Weidner N., Bogdahn U., Winkler J., Kuhn H. G., Aigner L. (2005). Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 1–14 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristo G. (2007). Development of cortical GABAergic circuits and its implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Clin. Genet. 72, 1–8 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B. L., Darlington R. B. (1995). Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science, 268, 1578–1584 10.1126/science.7777856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan V., Bredesen D. E. (2007). Neurogenesis in the adult brain: implications for Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 6, 303–310 10.2174/187152707783220938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Climent M. A., Castillo-Gómez E., Varea E., Guirado R., Blasco-Ibáñez J. M., Crespo C., Martínez-Guijarro F. J., Nácher J. (2008). A population of prenatally generated cells in the rat paleocortex maintains an immature neuronal phenotype into adulthood. Cereb. Cortex 18, 2229–2240 10.1093/cercor/bhm255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Martínez J. A., Möddel G., Ying Z., Prayson R. A., Bingaman W. E., Najm I. M. (2009). Neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression in resected epileptic dysplastic neocortex. J. Neurosurg. 110, 343–349 10.3171/2008.6.17608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A., Bonfanti L., Doetsch F., Caille I., Alvarez-Buylla A., Lim D. A., Galli R., Verdugo J. M., Herrera D. G., Vescovi A. L. (2002). Multipotent neural stem cells reside into the rostral extension and olfactory bulb of adult rodents. J. Neurosci. 22, 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattiangady B., Rao M. S., Shetty A. K. (2008). Plasticity of hippocampal stem/progenitor cells to enhance neurogenesis in response to kainite-induced injury is lost by middle age. Aging Cell 7, 207–224 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00363.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rabaza V., Llorens-Martín M., Velázquez-Sánchez C., Ferragud A., Arcusa A., Gumus H. G., Gómez-Pinedo U., Pérez-Villalba A., Roselló. J, Trejo J. L., Barcia J. A., Canales J. J. (2009). Inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis disrupts contextual learning but spares spatial working memory, long-term conditional rule retention and spatial reversal. Neuroscience 159, 59–68 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I. K., Yoo K. Y., Park O. K., Choi J. H., Lee C. H., Won M. H. (2009). Comparison of density and morphology of neuroblasts in the dentate gyrus among variously aged dogs, German shepherds. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 71, 211–215 10.1292/jvms.71.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger S., Gage F. H. (2008). Stem-cell-associated structural and functional plasticity in the aging hippocampus. Psychol. Aging 23, 684–691 10.1037/a0014188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopp A., Frahm C., Fidzinski P., Witte O. W., Behr J. (2008). Loss of GABAergic neurons in the subiculum and its functional implications in temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 131, 1516–1527 10.1093/brain/awn095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer L. (2009). In search of a unifying theory of complex brain evolution. Ann. NY. Acad. Sci. 1156, 44–67 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04421.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K., Zoncu R., Rakic P. (2002). Origin of GABAergic neurons in the human neocortex. Nature 417, 645–649 10.1038/nature00779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B., Kozorovitskiy Y., Gross C. G., Gould E. (2007). Diminished adult neurogenesis in the marmoset brain precedes old age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17169–17173 10.1073/pnas.0708228104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A., Campbell M. J., Foote S. L., Goldstein M., Morrison J. H. (1987). The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers in primate neocortex is widespread but regionally specific. J. Neurosci. 7, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A., Cruz D., Eggan S., Erickson S. (2004). Postnatal development of prefrontal inhibitory circuits and the pathophysiology of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Ann. NY. Acad. Sci. 1021, 64–76 10.1196/annals.1308.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A., Hashimoto T., Morris H. M. (2008). Cell and receptor type-specific alterations in markers of GABA neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Neurotox. Res. 14, 237–248 10.1007/BF03033813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. W., Curtis M. A., Gibbons H. M., Mee E. W., Bergin P. S., Teoh H. H., Connor B., Dragunow M., Faull R. L. (2008). Doublecortin expression in the normal and epileptic adult human brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 28, 2254–2265 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo P. M., Alonso M., Grubb M. S. (2006). Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 179–193 10.1038/nrn1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge D. J., Behrens M. M., Grace A. A. (2009). A loss of parvalbumin-containing interneurons is associated with diminished oscillatory activity in an animal model of schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 29, 2344–2354 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5419-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati F., Bonfanti L., Fasolo A., Peretto P. (2009). DCX and PSA-NCAM expression identifies a population of neurons preferentially distributed in associative areas of different pallial derivatives and vertebrate species. Cereb. Cortex 19, 1028–1041 10.1093/cercor/bhn145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magavi S. S., Leavitt B. R., Macklis J. D. (2000). Induction of neurogenesis in the neocortex of adult mice. Nature 405, 951–955 10.1038/35016083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magavi S. S., Mitchell B. D., Szentirmai O., Carter B. S., Macklis J. D. (2005). Adult-born and preexisting olfactory granule neurons undergo distinct experience-dependent modifications of their olfactory responses in vivo. J. Neurosci. 25, 10729–10739 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. (1978). Dual origin of the mammalian neocortex and evolution of the cortical plate. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 152, 109–126 10.1007/BF00315920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri M. N., Passarotti A. (2008). Neural bases of emotional processing in pediatric bipolar disorder. Expert Rev. Neurother. 8, 1381–1387 10.1586/14737175.8.9.1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekcec A., Löscher W., Potschka H. (2006). Neurogenesis in the adult rat piriform cortex. Neuroreport 17, 571–574 10.1097/00001756-200604240-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera T. D., Park S., Nemirovskaya Y. (2008). Cognitive role of neurogenesis in depression and antidepressant treatment. Neuroscientist 14, 326–338 10.1177/1073858408317242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierani A., Wassef M. (2009). Cerebral cortex development: from progenitors patterning to neocortical size during evolution. Dev. Growth Differ. 51, 325–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G., O'Dwyer G., Teleki Z., Stockmeier C. A., Miguel-Hidalgo J. J. (2007). GABAergic neurons immunoreactive for calcium binding proteins are reduced in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 471–482 10.1038/sj.npp.1301234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribak C. E., Shapiro L. A. (2008). Newly generated neurons in the dentate gyrus of aged epileptic Sprague-Dawley rats. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 122.25. [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M., O'Leary O. F., Knuuttila J. E., Castrén E. (2007). Chronic antidepressant treatment selectively increases expression of plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Neuroscience 144, 368–374 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G., Saricicek A. (2007). GABAergic contributions to the pathophysiology of depression and the mechanism of antidepressant action. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 6, 127–140 10.2174/187152707780363294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T., Namba T., Mochizuki H., Onodera M. (2007). Clustering, migration, and neurite formation of neural precursor cells in the adult rat hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 502, 275–290 10.1002/cne.21301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L. A., Korn M. J., Shan Z., Ribak C. E. (2005). GFAP-expressing radial glia-like cell bodies are involved in a one-to-one relationship with doublecortin-immunolabeled newborn neurons in the adult dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 1040, 81–91 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L. A., Ng K., Zhou Q. Y., Ribak C. E. (2008). Subventricular zone-derived, newly generated neurons populate several olfactory and limbic forebrain regions. Epilepsy Behav. 14, 74–80 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L. A., Ng K. L., Kinyamu R., Whitaker-Azmitia P., Geisert E. E., Blurton-Jones M., Zhou Q. Y., Ribak C. E. (2007). Origin, migration and fate of newly generated neurons in the adult rodent piriform cortex. Brain Struct. Funct. 212, 133–148 10.1007/s00429-007-0151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors T. J., Miesegaes G., Beylin A., Zhao M., Rydel T., Gould E. (2001). Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 410, 372–376 10.1038/35066584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebzehnrubl F. A., Blumcke I. (2008). Neurogenesis in the human hippocampus and its relevance to temporal lobe epilepsies. Epilepsia 49, 55–65 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M., Czéh B., Fuchs E. (2005). Age-dependent susceptibility of adult hippocampal cell proliferation to chronic psychosocial stress. Brain Res. 1049, 244–248 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwak-Tapp C. T., Head E., Muggenburg B. A., Milgram N. W., Cotman C. W. (2007). Neurogenesis decreases with age in the canine hippocampus and correlates with cognitive function. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 88, 249–259 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikandarajah N., Martinian L., Sisodiya S. M., Squier W., Blumcke I., Aronica E., Thom M. (2009). Doublecortin expression in focal cortical dysplasia in epilepsy. Epilepsia doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02194.x 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonchev A. B., Yamashima T., Zhao L., Okano H. J., Okano H. (2003). Proliferation of neural and neuronal progenitors after global brain ischemia in young adult macaque monkeys. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 23, 292–301 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00058-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varea E., Blasco-Ibáñez J. M., Gómez-Climent M. A., Castillo-Gómez E., Crespo C., Martínez-Guijarro F. J., Nácher J. (2007). Chronic fluoxetine treatment increases the expression of PSA-NCAM in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 803–812 10.1038/sj.npp.1301183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong K., Luo D. W., Patrylo P. R., Luo X. G., Struble R. G., Clough R.W., Yan X. X. (2008). Doublecortin-expressing cells are present in layer II across the adult guinea pig cerebral cortex: partial colocalization with mature interneuron markers. Exp. Neurol. 211, 271–282 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmazer-Hanke D. M., Faber-Zuschratter H., Blümcke I., Bickel M., Becker A., Mawrin C., Schramm J. (2007). Axo-somatic inhibition of projection neurons in the lateral nucleus of amygdala in human temporal lobe epilepsy: an ultrastructural study. Exp. Brain Res. 177, 384–399 10.1007/s00221-006-0680-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]