Summary

In many cases, the level, positioning and timing of signaling through the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway are regulated by molecules that bind BMP ligands in the extracellular space. Whereas many BMP-binding proteins inhibit signaling by sequestering BMPs from their receptors, other BMP-binding proteins cause remarkably context-specific gains or losses in signaling. Here, we review recent findings and hypotheses on the complex mechanisms that lead to these effects, with data from developing systems, biochemical analyses and mathematical modeling.

Introduction

Molecules that bind to bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) in the extracellular space can regulate the level, positioning and timing of BMP signals, and, thereby, developmental patterning events. In most cases, extracellular BMP-binding proteins act as inhibitors of signaling by sequestering BMPs from their receptors or by reducing the movement of BMPs from cell to cell (Table 1). More puzzling, however, has been the growing number of BMP-binding proteins that stimulate or inhibit signaling in a context-specific fashion. A great deal of effort has been spent investigating the mechanisms by which these proteins act, and there have been a flurry of recent papers that expand the range of possible mechanisms, provide new intriguing players in specific pathways, or demonstrate the importance of these mechanisms in new developmental contexts. However, the mechanisms underlying these effects are still often the subject of debate. It is the purpose of this review to highlight some of the latest findings and hypotheses in this field, concentrating particularly on the BMP-binding proteins that promote signaling in certain contexts (please also see Box 1 for other reviews on TGFβ signaling published in this issue).

Table 1.

BMP-binding proteins

| Component | Known effects on signaling | Properties/mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

|

Diffusible proteins |

||

| Noggina,b,c | Inhibit | Blocks BMP binding to receptors |

| Twisted gastrulationb,d | Inhibit/promote | Enhances BMP binding to Sog/Chordin and Tld/Xld cleavage of Sog/Chordin |

| Follistatinc |

Inhibit |

Forms BMP trimer with receptors |

| Soluble CR-containing proteins: | ||

| Chordin/Soga,b,c | Inhibit/promote | Blocks BMP binding to receptors; facilitates BMP shuttling |

| Chordin-like/Ventroptin/Neuralina,b,c | Inhibit | Binds BMPs |

| Chordin-like 2a,b,c | Inhibit | Binds BMPs |

| CTGFa,b | Inhibit | Blocks BMP binding to receptors |

| Nella,e |

Synergistic with BMP? |

CR domains, unknown binding |

| Can family: | ||

| Danb,c | Inhibit | Binds BMPs |

| Cerberus/Carontec,g | Inhibit/promote | Likely to bind BMP2/4/7 |

| PRDCb | Inhibit | Binds to BMP2/4 |

| Dand5/Coco/Danteb | Inhibit | Likely to bind BMPs |

| Gremlinb | Inhibit | Strong binding to BMP2/4/7 |

| Sclerostinb,c | Inhibit? Indirect? | Binds BMP2/4/5/6/7 |

| Sclerostin domain containing 1c,f |

Inhibit |

Binds BMPs |

|

Membrane/matrix-associated proteins |

||

| Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs): | ||

| Glypicans/Dally/Dlp/LON-2, syndecansh,i,j,k,l |

Inhibit/promote |

Binds BMPs; increases or decreases BMP movement |

| Chondroitin sulfate small leucine-rich proteins: | ||

| Biglycanm | Inhibit/may promote? | Binds BMP4 and Chordin; enhances formation of BMP4-Chordin complex |

| Tsukushin | Inhibit/may promote? | Binds BMP4/7 and Chordin; forms BMP-Tsukushi-Chordin complex |

| TβRIII (Betaglycan)o |

Promote |

Binds BMP2/4/7. Co-receptor? |

| Membrane-bound CR-containing proteins: | ||

| Crim1/Crm1p,q | Inhibit/promote | Binds BMPs, can block BMP processing and secretion |

| Procollagen-IIAr,s |

Inhibit |

Strongly binds BMP2 |

| CR-containing proteins with indirect membrane association: | ||

| Cv2 (BMPER)t,u | Inhibit/promote | Binds BMP2/4/7, HSPGs, Chordin/Sog, vertebrate Tsg, type I receptor |

| KCP/Kielinv,w |

Inhibit/promote |

Binds BMP7, Activin A, TGFβ1 |

| Other co-receptors and pseudoreceptors: | ||

| Dragon/RGMsx,y,z | Inhibit?/promote | Binds type I and II receptors, BMP2/4 |

| BAMBIaa |

Inhibit |

Binds type I receptor and blocks formation of the receptor complex |

| Bone or enamel extract-derived proteins: | ||

| GLAbb,cc | Inhibit | Binds BMP2/4 |

| SPP2dd | Inhibit | Unknown |

| Dermatopontinee | Inhibit | Unknown |

| Ahsgff,gg | Inhibit | Binds BMP and blocks signaling |

| Amelogeninhh |

Promote |

Binds heparan sulfate and BMP2 |

| Other matrix proteins: | ||

| Collagen IVii | Inhibit/promote | Binds Sog (Chordin) and Dpp (BMP) |

| Fibrillinjj,kk | May promote? | Binds BMP/prodomain complexes |

The diffusible and membrane/matrix-associated categories are based on binding data, known range or predicted range of action, but this is not always clear-cut. Different categorizations have been used based on cysteine-knot structure: Can-family members have an eight-member ring, whereas Tsg has nine and CR domains form ten-member rings (Avsian-Kretchmer and Hsueh, 2004). The solidus between names indicates alternate names or homologs in different species. aReviewed by Garcia Abreu et al., 2002; breviewed by Gazzerro and Canalis, 2006; creviewed by Balemans and Van Hul, 2002; dVilmos et al., 2001; eCowan et al., 2007; fYanagita, 2005; gYu et al., 2008; hPaine-Saunders et al., 2000; iFujise et al., 2001; jKirkpatrick et al., 2006; kGumienny et al., 2007; lFisher et al., 2006; mMoreno et al., 2005; nOhta et al., 2004; oKirkbride et al., 2008; pFung et al., 2007; qWilkinson et al., 2003; rSieron et al., 2002; sZhu et al., 1999; tMoser et al., 2003; uSerpe et al., 2008; vLin et al., 2005; wMatsui et al., 2000; xBabitt et al., 2005; ySamad et al., 2005; zKanomata et al., 2009; aaOnichtchouk et al., 1999; bbYao et al., 2008; ccWallin et al., 2000; ddBrochmann et al., 2009; eeBehnam et al., 2006; ffRittenberg et al., 2005; ggSzweras et al., 2002; hhSaito et al., 2008; iiWang et al., 2008; jjArteaga-Solis et al., 2001; kkSengle et al., 2008a.

Box 1. Minifocus on TGFβ signaling

This article is part of a Minifocus on TGFβ signaling. For further reading, please see the accompanying articles in this collection: `Informatics approaches to understanding TGFβ pathway regulation' by Pascal Kahlem and Stuart Newfeld (Kahlem and Newfeld, 2009); `The regulation of TGFβ signal transduction' by Aristidis Moustakas and Carl-Henrik Heldin (Moustakas and Heldin, 2009); and `TGFβ family signaling: novel insights in development and disease', a review of a recent FASEB Summer Conference on TGFβ signaling by Kristi Wharton and Rik Derynck (Wharton and Derynck, 2009).

In order to delineate the mechanisms by which BMP-binding proteins act, the field has increasingly turned to systems biology and predictive mathematical models. Such models have been used to analyze the effects of BMP-binding proteins both on the dynamics of non-uniform BMP distributions in tissues and on the local, single-cell dynamics of BMP reception. As modeling pertains to all our specific examples of BMP regulation, we begin with a brief review of some of the issues raised by a mathematical approach. Then, we review examples of BMP-binding proteins that regulate: (1) the initial activation and release of BMPs; (2) the transport of BMPs through tissues; and (3) the reception of the BMP signal.

Quantitative modeling of BMP regulation during development

Models of BMP signaling have been used in several different ways. By requiring models to meet quantifiable performance objectives, such as reproducibility, robustness and scale invariance (preservation of proportion), these models have been used to test mechanisms of BMP regulation and to identify experimentally testable aspects of the signaling pathways (Ben-Zvi et al., 2008; Eldar et al., 2002; Lander, 2007; Mizutani et al., 2005; Reeves et al., 2006; Schmierer et al., 2008; Serpe et al., 2008; Shimmi et al., 2005b; Umulis, 2009; Umulis et al., 2006; Umulis et al., 2008). Models have also been used to simulate aspects of patterning that are otherwise not easily observed, such as the dynamics of signaling or the distribution of protein-protein complexes (Eldar et al., 2002; Iber and Gaglia, 2007; Mizutani et al., 2005; Umulis et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007), or to measure biophysical parameters (Kicheva et al., 2007; Schmierer et al., 2008).

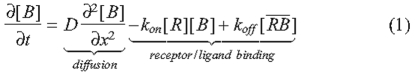

Such models vary greatly in the geometry, length scales, time scales and types of extracellular regulatory molecules being simulated, but they all rely on signaling via the binding of BMPs to transmembrane receptors. The process of diffusion with BMP-receptor binding has been extensively studied, and we provide the equations here for convenience and discussion (Lander et al., 2002; Umulis, 2009):

The BMP ligand [B] binds to immobile receptors [R] with the forward binding rate kon to form receptor-BMP complexes [RB], which dissociate with the rate koff. In models of BMP distribution along tissues, the conditions at the boundaries of the tissue most often include constant secretion of B from a source and no loss of B at the other boundary (Lander et al., 2002). BMP turnover is thought to be predominantly accomplished by the internalization and degradation of BMP-bound receptors; at present, no extracellular proteases that specifically target ligands of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily for destruction have been identified. Receptor internalization is modeled as a constitutive process in which both ligand-bound and unbound receptors are internalized at a constant rate ke (Akiyama et al., 2008; Lander et al., 2002; Mizutani et al., 2005). If resupply of receptors to the surface is also constant, then the total receptor level [RT] is constant, and one can use the dissociation constant KD to calculate the fraction (f) of occupied receptors after binding, and dissociation reaches equilibrium for any given level of extracellular ligand [B] (Lander et al., 2002; Umulis, 2009):

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

The KD for some BMP-receptor interactions has been measured, as has the KD for interactions between BMPs and many other BMP-binding proteins (Table 2). The data suggest that the binding between the BMP2/4 ligands and their receptor, BMPR1A, is tight, with a KD between 1 and 50 nM. These values, however, raise problems. If we first consider the case of negligible endocytosis, the fraction of occupied receptors is dictated solely by the dissociation constant and the level of BMP. Dissociation constants in the 1 nM range suggest that BMPs in the presumed physiological range (1-30 nM) would saturate receptors. This contrasts sharply with the demonstration that Activin, another member of the TGFβ superfamily, activates target genes by binding to between 2 and 6% of the total available receptors in Xenopus animal cap cells (Dyson and Gurdon, 1997). Mathematical analyses also suggest that 80% receptor occupancy is a reasonable maximum for morphogen-mediated patterning (Lander et al., 2002).

Table 2.

Binding, dissociation and kinetic constants for BMPs and BMP-binding molecules

|

Binding reaction |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immobilized* | Perfused | kon × 10−3 (nM−1 second−1) | koff × 10−3 (second−1) | KD (nM) | Reference | |

| BMPR1A | + | BMP2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.7 | Kirsch et al., 2000 |

| BMP2 | + | BMPR1A | 0.03 | 0.3 | 10 | Saremba et al., 2008 |

| BMP4 | + | BMPR1A | 0.028 | 1.3 | 47 | Hatta et al., 2000 |

| BMP7 | + | BMPR1A | − | − | ~104 | Saremba et al., 2008 |

| BMPR1A | + | BMP7 | − | − | ~10-100 | Sebald et al., 2004 |

| BMPR2 | + | BMP2 | >1 | >10 | ~100 | Kirsch et al., 2000 |

| Cvl2 | + | BMP2 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 1.4 | Rentzsch et al., 2006 |

| Cvl2 | + | BMP4 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 2.0 | Rentzsch et al., 2006 |

| Cvl2 | + | BMP7 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 3.5 | Rentzsch et al., 2006 |

| BMP2 | + | Cvl2 | 0.081 | 1.8 | 22 | Rentzsch et al., 2006 |

| BMP2 | + | Chordin | 0.28 | 3.4 | 12 | Rentzsch et al., 2006 |

| BMP2 | + | Chordin | − | − | 20 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Chordin | + | BMP2 | − | − | 37 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Chordin | + | BMP7 | − | − | 46 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Dpp | + | Viking | 0.0039 | 2.9 | 746 | Wang et al., 2008 |

| Dpp | + | Dcg1 | 0.0032 | 2.1 | 647 | Wang et al., 2008 |

| BMP4 | + | HuColl IV | 0.028 | 2.5 | 92 | Wang et al., 2008 |

| TβRIII (HSPG) | + | BMP2 | 0.0019 | 16.9 | 9037 | Kirkbride et al., 2008 |

| Chordin | + | Cv2 | − | − | 1.4 | Ambrosio et al., 2008 |

| Tsg | + | BMP2 | − | − | 50 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Tsg | + | BMP7 | − | − | 28 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Tsg | + | Chordin | − | − | 50 | Zhang et al., 2007 |

| Heparin | + | BMP2 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 20 | Sebald et al., 2004 |

| BMP2 | + | Follistatin | 1.3 | 6.8 | 5.3 | Amthor et al., 2002 |

| BMP4 | + | Follistatin | 0.12 | 2.7 | 9.6 | Iemura et al., 1998 |

| BMP7 | + | Follistatin | − | − | 80 | Amthor et al., 2002 |

Dissociation constants measured using surface plasmon resonance can differ greatly depending on which molecule is immobilized to the chip. These differences may be caused by the effects of immobilization on the stoichiometry of binding.

The kinetics of BMP binding to, and dissociation from, receptors are also slow when compared with the kinetics of other BMP-binding proteins (Table 2). Tight binding with slow kinetics means that once bound to a receptor, BMPs would remain bound for long periods of time that could exceed the duration of the developmental process. This does not fit with the rapid loss of BMP observed during Drosophila embryo patterning (O'Connor et al., 2006) or after the blocking of BMPs in zebrafish embryos (Tucker et al., 2008).

A number of possible solutions to the problem of tight BMP-receptor binding have been suggested, including bucket-brigade signaling, whereby receptors play an active role in transporting BMPs along cell membranes by exchanging BMPs between adjacent receptors (Kerzberg and Wolpert, 1989), rapid endocytosis of BMP-bound receptors (Lander et al., 2002), signaling dominated by weakly binding BMPs, and BMP concentrations in the pM range ([B] KD) (Shimmi and O'Connor, 2003). However, the presence of BMP-binding proteins provides another solution. By sequestering BMPs from receptors, these may offset the saturation problem. Moreover, if receptor-ligand binding is mediated in part by the BMP-binding proteins, the faster kinetics associated with the binding proteins (Table 2) might allow for a more rapid response to the extracellular levels of the morphogen.

KD) (Shimmi and O'Connor, 2003). However, the presence of BMP-binding proteins provides another solution. By sequestering BMPs from receptors, these may offset the saturation problem. Moreover, if receptor-ligand binding is mediated in part by the BMP-binding proteins, the faster kinetics associated with the binding proteins (Table 2) might allow for a more rapid response to the extracellular levels of the morphogen.

Thus, BMP-binding proteins may play a crucial role in keeping BMP-receptor interactions and kinetics within a physiologically useful range. But if the role of such proteins is to reduce BMP-receptor interactions, how can some of these proteins also increase signaling? We will discuss several possible ways of stimulating signaling, first via changes in BMP activation and release, then via increases in BMP movement, and finally via increases in BMP reception.

Regulation of BMP activation and release

In theory, BMP-binding molecules could increase the activation and release of BMPs from secreting cells. However, relatively little has been published concerning this possibility, and most examples show inhibitory effects. BMPs form homodimers or heterodimers prior to secretion, but this is not known to be regulated, except by differential expression of different BMPs. Active BMPs are generated by the cleavage of a longer pre-protein into signaling and pro-domain fragments, and in vitro overexpression of vertebrate cysteine-rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 (CRIM1), a transmembrane BMP-binding protein, reduces cleavage of the BMP pre-protein, as well as increasing BMP levels on the cell surface and reducing BMP secretion (Wilkinson et al., 2003). It is not clear, however, whether this reflects the normal function of CRIM1. The phenotypes of CRIM1 knockdowns in mice and zebrafish have been difficult to interpret, and might indicate the involvement of CRIM1 in other pathways (Kinna et al., 2006; Pennisi et al., 2007; Wilkinson et al., 2007). Loss of an apparent CRIM1 homolog (CRM-1) from C. elegans actually reduces BMP signaling (Fung et al., 2007).

The pro-domain fragment created during the cleavage of the longer pre-BMP can itself be a BMP-binding protein, forming a secreted complex with the signaling fragment. Like the equivalent TGFβ complexes, some BMP complexes are inactive (or `latent'); these can be activated through cleavage of the propeptide by the extracellular protease BMP1 (Ge et al., 2005; Wolfman et al., 2003). However, other BMP complexes remain active; the purpose of the complex instead appears to be to tether the BMPs to components of the extracellular matrix (Gregory et al., 2005; Sengle et al., 2008a; Sengle et al., 2008b).

Regulation of BMP activity by secreted, diffusible binding proteins

Another way that BMP-binding proteins might increase signaling is by promoting BMP movement through tissues. In many developing organisms, a BMP gradient provides cell identity information through its ability to differentially activate downstream target genes in a concentration-dependent fashion, i.e. the morphogen concept (Ashe and Briscoe, 2006; Ibanes and Belmonte, 2008; Wolpert, 1969). Intriguingly, even molecules that on the one hand sequester BMPs and inhibit signaling can, on the other hand, also promote the movement of BMPs. This is easiest to understand for diffusible BMP-binding proteins, which can shuttle BMPs through the extracellular space by protecting them from receptor-mediated endocytosis and turnover (Lander et al., 2002; Mizutani et al., 2005) (reviewed by O'Connor et al., 2006). Blocking receptor-ligand interactions increases the half-life of the ligand, giving it more time to diffuse away from the producing cells.

Of course, such a strategy would not increase signaling unless the ligand can be released from the binding protein. This may be accomplished if the ligand and BMP-binding protein dissociate on a sufficiently rapid time scale, enabling the ligand to productively sample other nearby binding opportunities, such as receptors (see Table 2). However, the extent to which simple dissociation kinetics contributes to BMP gradient formation is unknown, and in some cases a more pro-active solution has evolved in which an extracellular protease cleaves the BMP-binding protein to release the ligand. The best-characterized examples of such a mechanism are the patterning of dorsal embryonic tissue and wing veins in Drosophila (reviewed by O'Connor et al., 2006) and the dorsal-ventral patterning of zebrafish and Xenopus embryos (reviewed by Little and Mullins, 2006). Such conservation of mechanism across phyla implies an ancient origin for this form of signal modulation (De Robertis, 2008; De Robertis and Sasai, 1996; Holley and Ferguson, 1997).

Regulation of BMP activity by Sog in Drosophila

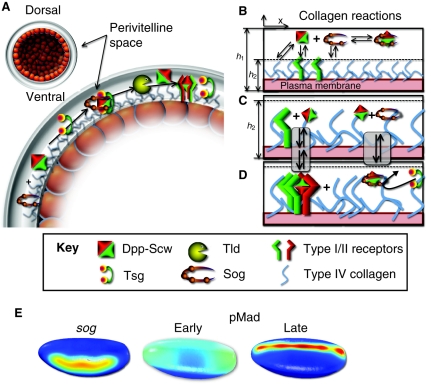

During early dorsal tissue patterning of the Drosophila embryo, the BMP-binding protein Short gastrulation (Sog) is secreted by cells located in the ventral-lateral region of the embryo, and diffuses to form a gradient (Francois et al., 1994; Srinivasan et al., 2002) (Fig. 1A,E). Sog inhibits signaling laterally, where levels are high, but promotes signaling dorsally, where levels are low. However, in cell culture, in which all cells have equal access to BMPs and Sog, Sog only inhibits signaling. Why does it act so differently in vivo?

Fig. 1.

Sog-mediated shuttling of BMPs and the role of membrane-localized reactions. (A) Schematic cross-section of the perivitelline (PV) space in the early Drosophila embryo. The BMP heterodimer Dpp-Scw is expressed broadly along the dorsal side (up), whereas Sog is expressed ventrolaterally (side). Binding of Sog to Dpp-Scw, and the subsequent flow of this complex from ventrolateral to dorsal cells, shuttles the BMPs from ventrolateral to the dorsal-most cells. This detailed view of the shuttling model includes Tsg in the Dpp-Scw-Sog complex, and dorsal cleavage of the complex by the Tld protease, freeing BMPs for signaling. (B) A detailed view of binding reactions between Dpp-Scw and Sog in the extracellular space, including ligand binding and release from membrane-bound type IV collagen, binding and release from signaling receptors, and binding and release from the Dpp-Scw-Sog complex. (C,D) The membrane binding and release processes taking place on type IV collagen. x, the position along the dorsal ventral axis; h1, the overall height of the PV space; h2, the height of collagen into the PV space. (E) Early Drosophila embryos, showing high (red) to medium (yellow, green) to low (blue) levels of Sog (left) and of BMP signaling as indicated by pMad (center and right), along the dorsoventral axis; dorsal is up and ventral is down. Initially, dorsal BMP signaling is broad and low, but ventrolateral Sog inhibits ventrolateral signaling and increases signaling in the dorsal-most cells. Dpp, Decapentaplegic; pMad, phosphorylated Mothers against decapentaplegic; Scw, Screw; Sog, Short gastrulation; Tsg, Twisted gastrulation; Tld, Tolloid.

The evidence indicates that Sog acts as a shuttle that moves BMPs from regions of high Sog to low Sog concentration (Shimmi et al., 2005a; Wang and Ferguson, 2005). Two BMP ligands are synthesized at this developmental stage: Decapentaplegic (Dpp), which is transcribed uniformly in the dorsal-most 40% of the Drosophila embryo, and Screw (Scw), which is ubiquitously produced by all cells of the blastoderm embryo. Both homo- and heterodimers of Scw and Dpp are envisioned to be produced in the dorsal domain and to contribute to cell fate specification within this region in different ways (Shimmi et al., 2005b). The Dpp-Scw heterodimer has the highest affinity for Sog and is therefore better protected from capture by receptor; thus, the heterodimer can travel further from its site of synthesis than either homodimer. Net flux of the heterodimer towards the dorsal midline is achieved through a cyclic process that involves BMP capture by Sog and release of the heterodimer through cleavage of Sog by the metalloprotease Tolloid (Tld). Once released, the heterodimer can either be recaptured by another Sog molecule or by receptors; the probability of either event happening depends on the local concentration of each component. In lateral regions (high Sog concentration), ligand recapture by Sog is favored and thus signaling is inhibited, whereas near the dorsal midline (low Sog concentration), ligand capture by receptors is favored. The net effect is ligand flux towards the dorsal midline, generating a region of high signaling near the midline that is provided primarily by heterodimers. Lower-level signaling is seen throughout the remainder of the dorsal domain due to homodimers, which might not be localized as tightly owing to lower affinities for Sog, slower cleavage of Sog, or weaker signaling.

BMP gradient formation in the Drosophila embryo has been the focus of a number of mathematical modeling studies (reviewed by O'Connor et al., 2006; Umulis et al., 2008), which have demonstrated the plausibility of the Sog `shuttling' mechanism. Intriguingly, mathematical models require very tight binding between the BMPs and the Sog or Sog co-factor shuttle, with dissociation constants ranging from 0 nM (irreversible binding) (Eldar et al., 2002) to 0.01 nM (Mizutani et al., 2005) to 0.03 nM (Umulis et al., 2006). If weaker binding is used in the models, the predicted distribution of BMPs is broad and low, reminiscent of the distribution of BMPs in sog mutant embryos. However, since these modeling studies were published, a dissociation constant of 12 nM has been determined for binding between the vertebrate Dpp homolog BMP2 and the vertebrate Sog homolog Chordin (Rentzsch et al., 2006) (Table 2). If binding between Sog and Dpp-Scw is similarly weak, how might the existing mathematical models be reconciled with the available data? The solution might rely on the recently discovered role of type IV collagen in the assembly of Dpp-Scw-Sog complexes.

Collagen and Dpp-Scw-Sog complex formation

The genes viking and Collagen type IV (Cg25C, also known as Dcg1) encode type IV collagen proteins that form a matrix in the early blastoderm embryo, and their reduction attenuates the high point of BMP signaling in the dorsal-most tissue (Wang et al., 2008). These collagens bind BMPs and Sog. Although there are several independent, but not mutually exclusive, ways that collagen might influence BMP signaling (Ashe, 2008), one intriguing possibility is that the collagen surface enhances the rate of Sog-BMP complex formation. Consider the proposed mechanism for collagen action shown in Fig. 1B-D, based on Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2008). Sog and Dpp-Scw are free to bind in solution or once attached to collagen. The overall kinetic rate constant for formation of the Dpp-Scw-Sog complex depends on the rate of Sog and Dpp/Scw molecular collisions and the proportion of collisions that successfully lead to the formation of the Dpp-Scw-Sog complex. Going from free diffusion to an attached site, such as collagen, would greatly reduce the diffusion rate of both Sog and Dpp-Scw, and that would tend to reduce the forward kinetic rate constant for binding (Lauffenberger and Linderman, 1993). However, three other factors could still provide a boost to the overall rate of complex formation owing to a reduction in the dimensionality effect (Grasberger et al., 1986; Kholodenko et al., 2000). The first is volume exclusion by other proteins located in the reduced volume occupied by collagen. The second is better alignment of functional protein subunits (orientated by collagen versus disoriented in solution). The final factor is local increases in concentration. The concentrating effect of collagen can greatly increase the formation of BMP-Sog complexes relative to that in free solution. Neglecting the contribution of Dpp-Scw-Sog binding in solution, collagen-mediated formation leads to an effective dissociation constant:

|

(5) |

where VT is the total volume and VC is the reduced volume occupied by the collagen matrix. In Fig. 1B-D, the ratio VC to VT is equal to h1/h2, which could lead to an effective reduction of the dissociation constant by 50- to 100-fold, depending on how far collagen extends into the extracellular space.

However, just as Sog must be released from BMP by Tld processing to enable signaling, so too must the assembled Sog-BMP-collagen complex be rapidly dissociated into a free BMP-Sog complex in order for shuttling to take place. Another BMP-binding molecule, Twisted gastrulation (Tsg), appears to provide just such an activity. Found in Drosophila and vertebrates (TWSG1), members of the Tsg family have two distinct cysteine-rich (CR) domains separated by a spacer sequence (Vilmos et al., 2001). The N-terminal half can bind BMPs and shows some similarity to the BMP-binding CR domains of Chordin/Sog and other BMP-binding proteins (Table 1) (Oelgeschlager et al., 2000). The C-terminal CR domain is likely to fold into a different structure, the function of which remains ill-defined (Vilmos et al., 2001). Tsg-like proteins perform several functions that can either increase or decrease BMP signaling, including enhancing the binding of Chordin/Sog to BMPs through formation of a ternary complex (Larrain et al., 2001; Oelgeschlager et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2001; Scott et al., 2001). Intriguingly, Drosophila Tsg can displace Sog-BMP from collagen and, in the process, assemble itself into a ternary Sog-BMP-Tsg complex (Wang et al., 2008).

Chordin and scale invariance in amphibian embryos

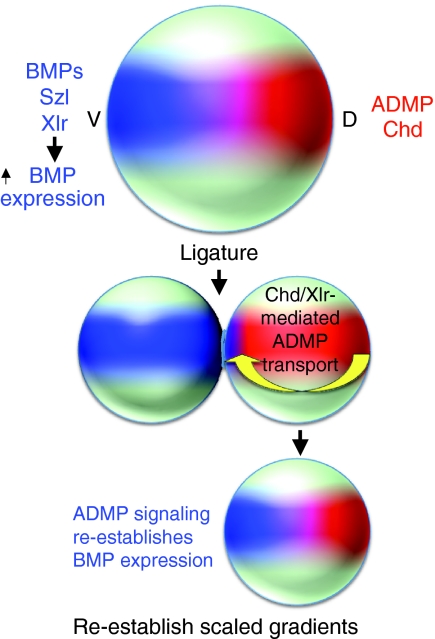

In zebrafish and Xenopus embryos, a similar set of BMPs provides patterning cues along the entire dorsal-ventral axis (reviewed by Little and Mullins, 2006). In these organisms, BMP4 and 7, along with the Xenopus Tld homolog Xolloid-related metalloprotease (Xlr, also known as Tll), are produced and secreted from ventral tissue, whereas BMP-binding proteins, including Follistatin, Noggin, Cerberus and the Sog homolog Chordin, are all produced in, and secreted from, a specialized dorsal tissue known as Spemann's organizer (Fig. 2). These two opposing signaling centers are thought to establish a graded BMP signal that assigns proper cell fate in a position-dependent manner.

Fig. 2.

Chordin-mediated BMP shuttling and its possible role in rescaling the dorsoventral axis of ligated Xenopus embryos. A schematic of a Xenopus embryo. BMPs, the Xlr protease and the Xlr inhibitor Szl are high ventrally (V, blue), whereas Chordin and the BMP ADMP are high dorsally (D, red). Following ligation, one model (Ben-Zvi et al., 2008) proposes that Chordin shuttles ADMP ventrally, where subsequent ADMP-mediated BMP signaling stimulates expression of BMPs; these then further reinforce their own expression to reform the gradient of signaling. Models that do not rely on shuttling have also been proposed (Kimelman and Pyati, 2005). ADMP, Anti-dorsalizing morphogenetic protein; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; Chd, Chordin; Szl, Sizzled; Xlr, Xolloid-like metalloprotease.

One remarkable feature of amphibian embryo development is its plasticity and capacity for regulative development in the face of drastic embryological manipulations. For example, initial embryological experiments by Hans Spemann and others at the beginning of the twentieth century demonstrated that ligature of early embryos into dorsal and ventral halves leads to very different fates for each section (reviewed by De Robertis, 2006). The ventral half developed into a `belly piece' comprising solely ventral tissue, whereas the dorsal half produced a well-proportioned, fully viable, half-sized tadpole that contained both dorsal and ventral tissue. The ability of dorsal-only tissue to regenerate the entire body axis remains, to this day, one of the most dramatic examples of developmental plasticity.

Recent theoretical, molecular genetic and embryological data have begun to provide a framework for understanding this remarkable regulative system. As in Drosophila, shuttling of BMP ligands by Chordin and Xld is thought to be central to the process, as is the BMP known as Anti-dorsalizing morphogenetic protein (ADMP) (Ben-Zvi et al., 2008; Reversade and De Robertis, 2005; Reversade et al., 2005). In contrast to several other BMPs, ADMP is expressed on the dorsal side of the Xenopus embryo in the organizer (Moos et al., 1995) and is under `opposite' transcriptional control compared with BMP4/7 (Reversade and De Robertis, 2005). Thus, low levels of BMP signaling are required for ADMP expression, whereas high levels of BMP signaling on the ventral side reinforce expression of BMP4/7. During normal development, BMP inhibitors, such as Chordin, are secreted from the organizer and keep BMP signal reception in the organizer low, allowing ADMP expression. However, Chordin can also increase the range of BMP movement (Ben-Zvi et al., 2008) and dorsally expressed ADMP can affect signaling in ventral cells (Reversade and De Robertis, 2005). In a ligature experiment, much of the ventral BMP-secreting tissue is removed, but a net flux of a complex of Chordin and ADMP from the dorsal side is envisioned to help re-establish a BMP signal to what will become the new ventral side of the `half' embryo. The transported ADMP is thought to activate expression of BMP4/7 (which in turn further reinforces BMP4/7 transcription), re-establishing a properly scaled developmental axis in the half-sized embryo. In this scenario, there is presumably enough Xlr or other Tld-like proteases present in the `half' embryo to effectively process Chordin, thereby releasing sufficient ADMP to initiate the formation of a new ventral signaling center.

Scaffolds for destruction of transport complexes

Recent mathematical modeling of the Drosophila and Xenopus dorsal-ventral patterning systems has suggested that in order for the shuttling model to meet scaling (Xenopus) or robustness (Drosophila) performance objectives, the processing of Chordin/Sog by the Tld/Xlr metalloproteases must be dependent on Chordin/Sog being bound to the ligand (Ben-Zvi et al., 2008; Eldar et al., 2002; Mizutani et al., 2005). In other words, Chordin/Sog that is not bound to a BMP must be an ineffective substrate for Tld/Xlr. Although this condition has been demonstrated to be true, at least in vitro, for the Drosophila proteins (Marques et al., 1997), it is not clear whether it holds for the Xenopus proteins. In fact, one of the first differences noted between the two systems was that Chordin is a good substrate for Xlr and other Tld-like proteases, even when it is not bound to a BMP ligand (Marques et al., 1997; Piccolo et al., 1997).

The situation has recently become even murkier with the demonstration that the secreted Xenopus protein ONT1 [also known as Olfactomedin-like 3 (OLFML3)] may provide a scaffold for specifically destroying Chordin, even when not bound to BMPs (Inomata et al., 2008). ONT1 is a member of a large family of secreted proteins related to Olfactomedin, the functions of which are largely undefined (Zeng et al., 2005). ONT1 contains at least two structural motifs: an N-terminal coiled-coil domain that binds Tld-like proteases and a C-terminal Olfactomedin domain that binds Chordin CR repeats (Inomata et al., 2008). Biochemical experiments show that the degree of Chordin processing by Tld-like proteases depends on the level of ONT1 in the reaction. In its absence, there is a background level of Chordin proteolysis and, as the ONT1 concentration is increased, the processing of Chordin first rises to a maximum and then decreases. This behavior fits nicely with a scaffold model in which assembly of Chordin and Tld onto ONT1 initially increases the rate of processing owing to effective presentation or local increases in the concentration of the substrate and protease. However, as ONT1 levels increase further (or the Chordin and Tld levels decrease), individual Chordin and Tld molecules bind to different ONT1 molecules, precluding effective proteolysis.

But if ONT1 promotes Chordin destruction in the absence of bound BMP, how can we meet the model requirement that only BMP-bound Chordin can be processed? Interactions with additional extracellular modulators of BMP signaling might provide the solution. For instance, Tsg can increase the rate of Chordin/Sog cleavage by Tld/Xld (Larrain et al., 2001; Shimmi and O'Connor, 2003; Scott et al., 2001). Thus, the effective in vivo processing rate of the ternary complex containing both Chordin and Tsg bound to ADMP (or other BMPs) might be significantly faster than the background processing rate of free Chordin or Chordin bound to ONT1. Another possibility is that the processing of Chordin is held in check by ventrally secreted Sizzled, a competitive inhibitor of Xlr that is not found in Drosophila (Lee et al., 2006; Mullins, 2006; Muraoka et al., 2006). Sizzled might lower the overall activity of Tld-like proteases, perhaps even when bound to ONT1, such that only BMP-Chordin or BMP-Chordin-Tsg are effective substrates from a kinetic point of view. Clearly, a more careful analysis of the processing kinetics for different types of BMP-Chordin-Tsg and Chordin-ONT1-Xld complexes is needed to resolve this issue.

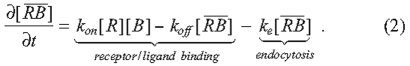

Context-dependent effects on BMP signal reception: Crossveinless 2

Modifying the transport of BMP ligands is not the only way that BMP-binding proteins regulate signaling. Some extracellular BMP-binding proteins can increase signaling in a relatively cell-autonomous fashion. Some probably act as co-receptors, increasing the binding of BMPs to the type I or type II BMP receptors. Indeed, the vertebrate TGFβ co-receptor TβRIII (TGFβR3), which lacks a Drosophila ortholog, was recently shown to promote BMP signaling (Kirkbride et al., 2008) (Table 1).

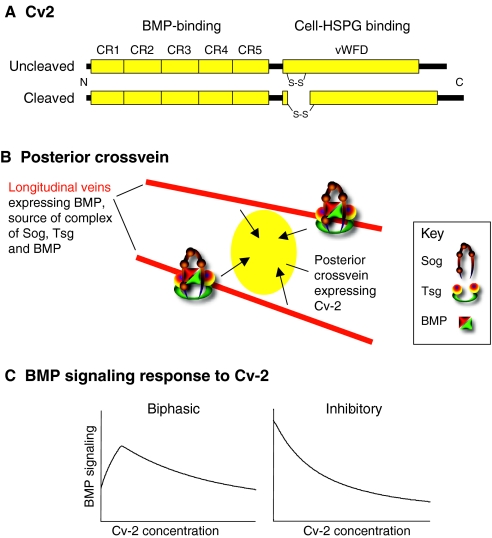

Yet some BMP-binding proteins either increase or decrease signal reception in a context-dependent manner. Much of the recent debate about possible mechanisms has centered on the Crossveinless 2 family of secreted proteins (Cv2, Cv-2 or Cvl2; now renamed BMPER in vertebrates) (Fig. 3). That debate is not settled, but has raised some interesting issues that might be applicable to other BMP-binding molecules. In short, one model is that BMP bound to Cv2 is in equilibrium with a transient ternary complex containing the type I BMP receptor (Serpe et al., 2008). This leads to exchange of BMPs between Cv2 and the receptor; depending on the Cv2 concentration and binding affinities, this exchange either sequesters BMPs from the receptors, or provides BMPs for the receptors. Another model, while agreeing that Cv2 inhibits signaling by sequestering BMPs, suggests that Cv2 increases signaling by a mechanism that is independent of BMP binding (Zhang et al., 2008), perhaps via interactions with Chordin/Sog or Tsg (Ambrosio et al., 2008; Zakin et al., 2008). It is entirely possible that both models are correct.

Fig. 3.

Structure and activity of Cv2. (A) Structure of the uncleaved and cleaved versions of secreted Cv2. CR, cysteine-rich domain; vWFD, von Willebrand Factor D domain; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan. (B) Model of posterior crossvein (PCV) development in the pupal Drosophila wing. BMPs - probably a mixture of Dpp, Gbb and Dpp-Gbb heterodimers - are transported from the adjacent longitudinal veins (red) into the PCV (yellow) by a complex of Sog and a second Drosophila Tsg protein called Crossveinless (Tsg2), where it is released for signaling by the Tolloid-related protease (not shown). Drosophila Cv-2 is expressed in the PCV region, where it locally increases BMP signaling, leading to PCV formation. (C) Changes in BMP signaling in response to increasing concentrations of Cv-2. Increasing Cv-2 concentration can cause either a biphasic response (left), in which BMP signaling initially increases before being inhibited with increasing Cv-2 concentration, or a purely inhibitory response (right). BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; Cv2, Cv-2 (Crossveinless 2; BMPER); Sog, Short gastrulation; Tsg, Twisted gastrulation.

Cv2 proteins bind BMPs via one or more of five closely spaced N-terminal CR domains, and also bind heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) that are present at the cell surface via a C-terminal von Willebrand Factor D domain (vWFD) (Coffinier et al., 2002; Conley et al., 2000; Moser et al., 2003; Rentzsch et al., 2006; Serpe et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008) (Fig. 3A). Despite some structural differences, Drosophila Cv-2 can function in zebrafish embryos (Rentzsch et al., 2006). Cv2 proteins are similar to the Kielin-Chordin-like proteins (KCPs) found in vertebrates, urochordates and echinoderms, except that KCP proteins have many more CR domains (Lin et al., 2005; Matsui et al., 2000).

Drosophila Cv-2 got its name from stimulating BMP signaling in the pupal wing: it is expressed in the developing ectodermal crossveins (Fig. 3B), and cv-2 mutations reduce BMP signaling, causing a crossveinless phenotype (Conley et al., 2000; Serpe et al., 2008). Sog and a second Drosophila Tsg protein (Crossveinless) also promote signaling in the crossvein, probably by transporting Dpp and the BMP7-like Glass bottom boat (Gbb) from the adjacent longitudinal veins (Ralston and Blair, 2005; Serpe et al., 2005; Shimmi et al., 2005a; Vilmos et al., 2005). But mosaic analyses have shown that Drosophila Cv-2 is not required for BMP transport; instead, Cv-2 acts near the BMP-receiving cells (Serpe et al., 2008). Drosophila Cv-2 and mammalian Cv2 or KCP can also increase signaling in vitro, where most cells have access to the BMP in the medium and Cv-2 does not affect Sog cleavage (Heinke et al., 2008; Ikeya et al., 2006; Kamimura et al., 2004; Serpe et al., 2008).

But Cv2 proteins are not simple co-receptors, as they can also inhibit signaling. Cv2 regulates BMP signaling in early axis formation in Xenopus (Ambrosio et al., 2008), as well as axis formation, hematopoiesis and vascular development in zebrafish (Moser et al., 2007; Rentzsch et al., 2006), neural crest formation in chick (Coles et al., 2004) and skeletogenesis in mice (Ikeya et al., 2006; Ikeya et al., 2008; Zakin et al., 2008). But the direction of that modulation varies, even in contexts that appear homologous (e.g. largely anti-BMP in early Xenopus but largely pro-BMP in early zebrafish). Drosophila, zebrafish and mammalian Cv2 proteins can also inhibit signaling in some, but not all, in vitro assays (e.g. Binnerts et al., 2004; Esterberg and Fritz, 2009; Harada et al., 2008; Kelley et al., 2009; Moser et al., 2003; Serpe et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008).

Two conditions are known to influence Cv2 activity. The first is concentration. In Drosophila and in mammalian cell culture, the effect of changing Cv2 concentration can be biphasic: as the concentration of Cv2 increases, BMP signaling increases to a maximum and then decreases (Kelley et al., 2009; Serpe et al., 2008) (Fig. 3C). The second is the type of ligand: in Drosophila cell culture, signaling by the BMP7-like Gbb has a biphasic response to changes in Cv-2 concentration, whereas signaling by Dpp has a purely inhibitory response to Cv-2 (Serpe et al., 2008) (Fig. 3C). Mammalian KCP stimulates BMP signaling, but inhibits TGFβ and Activin signaling (Lin et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2006).

Cv2 is likely to inhibit signaling by sequestering BMPs from BMP receptors. High concentrations of mammalian Cv2 can increase the endocytosis and degradation of BMPs, probably by the binding of a Cv2-BMP complex to the cell surface via the vWFD domain of Cv2 (Kelley et al., 2009). Thus, Cv2 might clear enough BMP from the cell surface to reduce signaling. More direct effects are also likely, as a truncated zebrafish Cvl2 that lacks the vWFD domain can still block signaling in vitro; in fact, the most N-terminal CR domain of zebrafish Cvl2 competes with type I and type II BMP receptors for overlapping sites on BMPs (Zhang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008).

But how then can Cv2 increase signaling? One possibility is that the increases and decreases are mediated by different forms of Cv2. A fraction of the Cv2 secreted by cells is cleaved, probably by an autocatalytic process in late secretory compartments, into disulfide-linked N- and C-terminal fragments (Ambrosio et al., 2008; Binnerts et al., 2004; Rentzsch et al., 2006; Serpe et al., 2008) (Fig. 3A). The inhibitory effects of zebrafish Cvl2 can be increased by mutating the cleavage site and blocking Cvl2 processing (Rentzsch et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). However, an uncleavable form of Drosophila Cv-2 can still stimulate signaling (Serpe et al., 2008), so this cannot be the whole story.

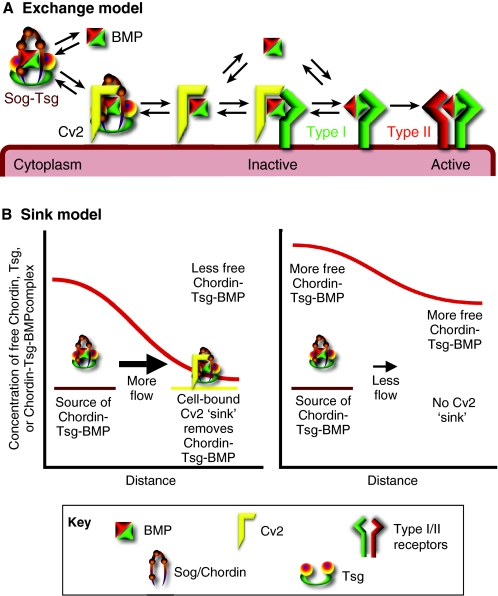

This has left two models. The first, the so-called exchange model (Fig. 4A), relies on the finding that Cv2 can bind to type I BMP receptors (Serpe et al., 2008) (see also Ambrosio et al., 2008). The close association between Cv2 and receptor may thus allow them to exchange BMPs (Fig. 4A) (Serpe et al., 2008). This is plausible given the available binding data: BMP-Cvl2 binding has a much higher koff rate than that between BMPs and type I receptors (Table 2), and these faster kinetics may lead to the dynamic exposure of receptor binding sites on the BMP.

Fig. 4.

Models of Cv2 activity. (A) The exchange model of Cv2 activity, in which binding between Cv2 and type I BMP receptors either increases the flow of BMPs to the receptors or sequesters BMPs in inactive complexes. The model also hypothesizes a similar exchange of BMPs between Cv2 and Chordin/Sog, mediated by binding between Cv2 and a Chordin/Sog-Tsg complex, which could increase the release of BMPs from Chordin/Sog, increasing the levels of Cv2-bound BMPs available for exchange with the BMP receptors. (B) The sink model of Cv2 activity. (Left) Cv2 is expressed at a distance from the region of BMP, Chordin/Sog and Tsg production. By binding Chordin/Sog, Tsg or a Chordin-Tsg-BMP complex (as shown), Cv2 locally reduces the concentration of free Chordin/Sog, Tsg or Chordin-Tsg-BMP complex. This will also result in an increase in the flow of the Cv2-binding proteins towards Cv2-expressing cells. (Right) In the absence of Cv2, the levels of free Cv2-binding proteins rise in both nearby and distant tissues, and, after levels reach an equilibrium, the net flow of the Cv2-binding proteins away from their region of production is reduced. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; Cv2 (Crossveinless 2; BMPER); Sog, Short gastrulation; Tsg, Twisted gastrulation.

A mathematical version of the exchange model can also produce biphasic dose-response curves, as long as the complex of Cv2, BMP and receptor has a greatly reduced ability to signal (Serpe et al., 2008). At low concentrations, Cv2 provides BMP for the receptor, whereas at high concentrations Cv2 sequesters BMPs. The model can also reproduce the ligand-dependence of Cv2 activity: when BMP-receptor binding parameters are used from the lower affinity Gbb-like BMP7, the response to Cv2 levels is biphasic; when the higher affinity Dpp-like BMP4 parameters are used, the response to Cv2 is inhibitory. An interesting implication of this model is that one BMP-binding protein might simultaneously reduce receptor binding for high-affinity BMPs, reducing the problem of receptor saturation, while simultaneously increasing the receptor binding of low-affinity BMPs. The model might also apply to other BMP-binding molecules; for example, Cerberus, previously thought to be purely inhibitory, can also promote BMP signaling and also binds type I receptors (Yu et al., 2008).

In an alternative model, Cv2 stimulates signaling independently of its ability to bind BMPs, perhaps via its interactions with molecules such as Chordin/Sog or Tsg. Support for this model comes largely from the observation that mutated forms of Drosophila Cv-2 and zebrafish Cvl2 that reduce BMP binding can still increase signaling in some assays (Serpe et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Moreover, mammalian Cv2 can bind vertebrate Tsg and Chordin, either singly or in complexes with BMPs (Ambrosio et al., 2008). Drosophila Cv-2 also binds to Drosophila Sog, although apparently not to the Drosophila Tsg proteins (S. M. Honeyager, M. Serpe, D. Olson and S.S.B., unpublished). The function of this binding is not yet clear and does not necessarily argue against the exchange model. In fact, binding might mediate the exchange of BMPs between Cv2, Chordin/Sog and Tsg in much the same way that exchange is hypothesized to occur between Cv2 and BMP receptors (Fig. 4A). The binding of Cv2 and Chordin/Sog cannot mediate all of the effects of Cv2 because, in zebrafish, Cvl2 can still promote signaling in the absence of Chordin (Rentzsch et al., 2006). Nonetheless, it is possible that some aspects of Cv2 activity are mediated by changes in the levels or activity of Chordin/Sog or Tsg in the extracellular space (see Ambrosio et al., 2008; Serpe et al., 2008; Zakin et al., 2008).

A variation on this hypothesis, the sink model (Fig. 4B), posits that a relatively immobile, cell-bound protein such as Cv2 could still act over a long range, affecting gradient formation by acting as a local sink for a protein or protein complex produced elsewhere. A sink can locally reduce the extracellular levels of proteins, increasing diffusion towards the sink and away from the source (Fig. 4B). This would not explain the activity of Cv2 in vitro, or in the crossveins, where uniform Drosophila Cv-2 overexpression can increase signaling after uniform overexpression of Sog and Tsg (Ralston and Blair, 2005; O'Connor et al., 2006; Shimmi et al., 2005a) (A. Ralston, PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsin, 2004). But in the Xenopus embryo, ventrally expressed Cv2 might act as a local sink for dorsally generated Chordin-BMP complexes (Ambrosio et al., 2008). The sink hypothesis might also explain some otherwise confounding results from mouse vertebral development. The levels of BMPs, Chordin, Tsg and BMP signaling are all initially highest in the condensed mesenchyme, the precursor of the intervertebral disc, whereas Cv2 levels are high in the complementary uncondensed mesenchyme, the precursor to the vertebral body (Zakin et al., 2008). Oddly, Cv2 knockouts reduced BMP signaling in the condensed mesenchyme, where Cv2 is not normally detected. One possibility is that without the distant sink provided by Cv2, Chordin or Tsg levels build up to abnormally high levels in the condensed mesenchyme, blocking signaling (Fig. 4B). An effect via excess Tsg would be consistent with the essentially normal vertebral development observed in Cv2 Tsg double knockouts (Ikeya et al., 2008; Zakin et al., 2008).

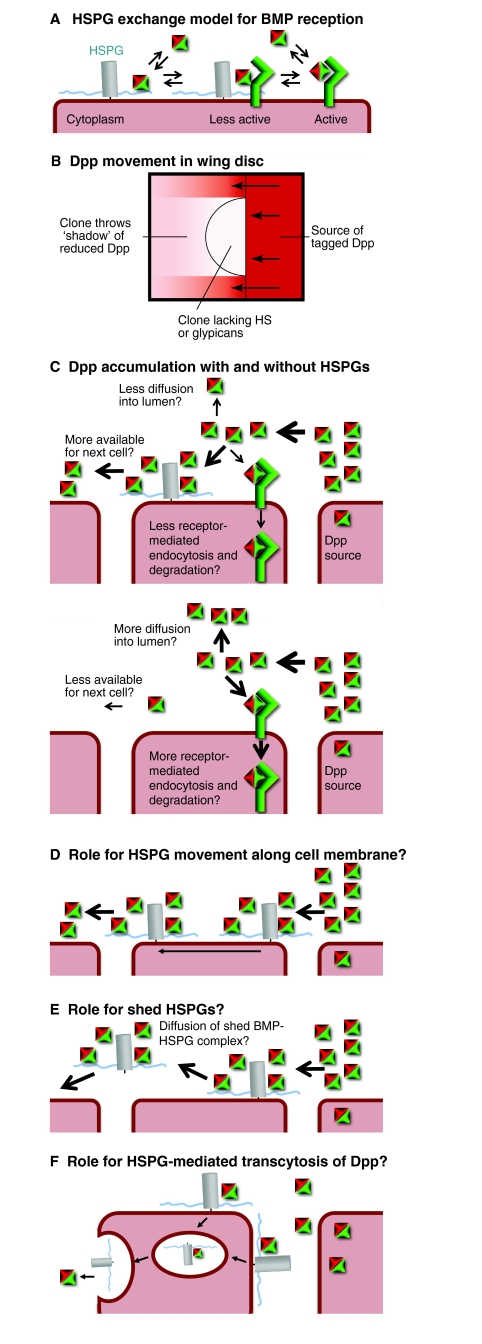

BMP reception and movement: context-dependent effects of proteoglycans

The debate about Chordin/Sog and Cv2 function has particular relevance to the study of another class of BMP-binding proteins, the proteoglycans (PGs) (reviewed by Esko and Selleck, 2002; Filmus et al., 2008; Gorsi and Stringer, 2007; Kirkpatrick and Selleck, 2007). This diverse family of carbohydrate-modified proteins has perplexingly complex effects on the BMP and other signaling pathways. PG core proteins can either be transmembrane, as with the syndecans, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked to the membrane, as with the glypicans (Fig. 4A), or secreted into the extracellular matrix, as with the perlecans and Biglycan. Unbranched glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, such as heparan sulfate (HS) or chondroitin sulfate (CS), are added to selected sites on the core protein by GAG co-polymerases; GAGs are further modified by sulfation and de-sulfation. The GAG heparin binds BMPs (Ruppert et al., 1996), and the protein core of the Drosophila glypican Dally binds Dpp (Kirkpatrick et al., 2006). As with Cv2, further complexity is added by the ability of GAGs to bind other BMP-binding proteins, including the vertebrate BMP inhibitor Noggin (Paine-Saunders et al., 2002), Chordin (but not Drosophila Sog), Drosophila Tsg (but not vertebrate Tsg) (Jasuja et al., 2004; Mason et al., 1997; Moreno et al., 2005) (R. Jasuja, PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsin, 2006) and vertebrate and Drosophila Cv2 (Rentzsch et al., 2006; Serpe et al., 2008). Noggin and Chordin are less effective at inhibiting signaling in vitro after reductions in HS or Biglycan function (Jasuja et al., 2004; Moreno et al., 2005; Viviano et al., 2004).

It is therefore not that surprising that reducing PG function - either by chemical or enzymatic removal of the GAGs, by removal of the enzymes responsible for GAG extension or sulfation, or by the removal of individual core proteins - can have opposite effects in different contexts. Some of the different effects caused by wholesale changes to GAGs might be due to the different roles of specific PG cores: e.g. Syndecan-4 versus Glypican-1 (O'Connell et al., 2007); TβRIII (Kirkbride et al., 2008); Biglycan (Moreno et al., 2005); Xenopus Syndican-1 versus Syndecan-4 and Glypican-4 (Olivares et al., 2009). But the effects of removing even a single PG, such as Syndecan-3, can be complex (Fisher et al., 2006). In fact, Xenopus BMP signaling has a biphasic response to changes in the concentration of the HSPG Syndecan-1 (Olivares et al., 2009).

PGs can either promote or inhibit BMP signaling in vitro, indicating a role in signal reception that is independent of any effect on BMP transport. Given the parallels with Cv2, it is tempting to invoke the Cv2 exchange model to explain the biphasic effects of PGs: PGs can either sequester BMPs from the receptors or, when concentrations are low enough, bind BMPs and provide them to the receptors (Fig. 5A). One caveat is that it is not known whether PGs can associate with BMP receptors to allow this type of exchange, although PGs can bind receptors in other signaling pathways. A second caveat is that only a few studies have controlled for the effect of PGs on the levels or activity of other BMP-binding proteins, and so PGs might act as scaffolds more akin to ONT1 or type IV collagen.

Fig. 5.

Putative roles for proteoglycans in BMP signaling. (A) The exchange model applied to the modulation of BMP signal reception by a membrane-bound glypican HSPG. (B) Reduced movement of tagged Dpp through a Drosophila wing disc clone that lacks heparan sulfate synthesis or the glypicans Dally and Dally-like (Dlp). (C-F) Models of how HSPGs promote BMP (Dpp) movement in Drosophila wing discs. (C) HSPGs prevent the loss of BMPs via either receptor-mediated endocytosis or diffusion out of the epithelium, increasing the levels available for the next cell. In the absence of HSPGs, less BMP is available for diffusion to the next cell. (D) HSPGs increase BMP diffusion across a single cell by moving along the membrane of that cell. (E) Diffusible HSPGs shuttle BMPs to adjacent cells. (F) HSPGs help mediate BMP transcytosis, increasing the levels of BMPs available for the next cell. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; Dpp, Decapentaplegic; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan.

In vivo, the situation is even more complicated as, unlike Drosophila Cv-2, PGs affect the movement of BMPs through tissues. Although BMPs are likely to have lower affinities for heparin than they do for their receptors (Table 2), cell-bound HSPGs might be expected to reduce BMP movement by tethering BMPs to cells or by increasing their endocytosis. Indeed, reducing the binding of BMP4 to HSPGs, either by removing the three N-terminal amino acids of BMP4, or by digesting HS-GAGs with heperatinase, allows BMP4 to signal over a longer range in Xenopus animal caps (Ohkawara et al., 2002). The absence of HSPGs from early Drosophila embryos may also speed BMP movement (Bornemann et al., 2008). Signaling in the embryo is established in minutes, whereas in HSPG-containing tissues, such as the late third instar wing disc, the formation of long-range gradients takes hours (Lecuit and Cohen, 1998; Teleman and Cohen, 2000).

However, glypican HSPGs in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc also confound simple predictions, as they increase the range over which BMPs (and other signaling molecules) accumulate. Before pupariation, Dpp is expressed in a region just anterior to the anterior-posterior compartment boundary, and this produces a gradient of extracellular Dpp that runs through most of the disc (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Teleman and Cohen, 2000). The levels of extracellular BMPs are reduced around wing disc cells that lack either the enzymes required for HS synthesis or the two Drosophila glypicans Dally and Dally-like (Dlp) (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Fujise et al., 2001). Although, in theory, the reduced accumulation of Dpp could be caused by its faster diffusion through the mutant tissue (Lander, 2007), this does not appear to be the case. If a clone of HS-deficient or glypican-deficient cells is placed between a zone of Dpp expression and a group of receptive wild-type cells, the clone throws a `shadow' - a zone of wild-type cells with reduced levels of extracellular BMPs and reduced BMP signaling (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Bornemann et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004) (Fig. 5B). Reducing the binding of Dpp to HSPGs by removal of the seven N-terminal amino acids of Dpp reduces its range of movement, lowers its accumulation and increases its rate of loss from the cell surface (Akiyama et al., 2008).

Indirect effects via Sog, Tsg or Cv-2 are unlikely, as these play no obvious role during BMP signaling in the Drosophila wing disc at these stages (Shimmi et al., 2005a; Serpe et al., 2008; Vilmos et al., 2005; Yu et al., 1996). Nonetheless, something like the Chordin/Sog shuttling model might be operating here: the HSPGs could increase BMP movement by increasing the levels present in the extracellular space, raising the concentration available to diffuse to adjacent cells (Fig. 5C). As envisioned with Chordin/Sog, HSPGs could compete BMPs away from receptor-mediated endocytosis and degradation (Akiyama et al., 2008). And yet, if BMPs bind strongly enough to PGs to block receptor-mediated endocytosis, one might expect equally strong inhibition of receptor-mediated signaling. Signaling should therefore increase in a clone lacking HSPGs, at least at the edge near the source of Dpp; however, this has not been observed (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Bornemann et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004). Another possibility is that HSPGs reduce BMP loss by means other than reducing receptor binding, such as by reducing the diffusion of BMPs away from the single-cell layered wing disc epithelium. But either way, the BMPs that are bound to cell-bound PGs must also be free to move to adjacent cells (Eldar and Barkai, 2005; Hufnagel et al., 2006).

Several other proposals have been put forward and there is as yet no consensus about which model is correct. One proposal is that the diffusion of HSPGs within a single cell membrane increases the rate of BMP transport (Fig. 5D). Although unhindered diffusion for a BMP may be on the order of 10-100 μm2 second-1, it is conceivable that tortuosity, additional binding sites and other factors could scale down the diffusion of extracellular BMP to an effective diffusion rate that would be slower than that of membrane-associated glypicans. The diffusion of proteins associated with a membrane is on the order of 0.1 μm2 second-1, similar to that measured for Dpp-GFP in the wing imaginal disc (Kicheva et al., 2007). This still requires, however, the transfer of BMPs between HSPGs on adjacent cells.

Another proposal is that HSPGs are not cell-bound and thus can shuttle BMPs directly from cell to cell (Fig. 5E). GPI-linked glypicans can be shed from cells, at least in part owing to cleavage of the GPI link by extracellular proteases such as Notum (Kreuger et al., 2004; Traister et al., 2007). That said, the range of Dpp signaling is not obviously reduced in wing discs lacking Notum (Gerlitz and Basler, 2002; Giraldez et al., 2002). Moreover, expression of an engineered form of the glypican Dally that should remain linked to the cell surface still promotes Dpp signaling, whereas a constitutively secreted form actually inhibits signaling (Takeo et al., 2005). Glypicans can also be GPI-linked to extracellular lipid-containing lipoprotein particles, but reducing the levels of lipoproteins does not obviously reduce the range of BMP signaling in the wing disc (Eugster et al., 2007; Panakova et al., 2005).

A final alternative is that binding to HSPGs traffics BMPs and other ligands through tissues via transcytosis, rather than through the extracellular space (Fig. 5F). In this view, there is significant recycling of endocytosed HSPG-bound BMPs, resulting in the movement of BMPs through cells; it is the BMP movement through cells, rather than around cells, that forms a long-range gradient in the plane of the wing disc epithelium (Entchev et al., 2002; Kicheva et al., 2007). There has been a robust debate about the importance of planar transcytosis for gradient formation. The evidence for it is based on the effects of reduced endocytosis on Dpp movement and the formation of shadows of lower Dpp accumulation. There are disagreements about the data, and about the ability of purely diffusive models to explain the data (Belenkaya et al., 2004; Entchev et al., 2000; Kicheva et al., 2007; Kruse et al., 2004; Lander et al., 2002; Marois et al., 2006; Torroja et al., 2004). Nonetheless, planar transcytosis remains an intriguing possibility. Transcytosis might also affect signaling by moving BMPs between apical and basal compartments, as has been suggested for Hedgehog signals (Gallet et al., 2008).

Conclusions

Increasingly, new data show that extracellular regulators of BMP signaling have multi-purpose, context-dependent roles. The diffusible BMP-binding proteins Sog and Chordin block signaling near the sites of production, but also redistribute BMP ligands to increase their concentration at distances far from the site of Chordin/Sog secretion. Relatively immobile molecules, such as collagen and ONT1, can nonetheless facilitate BMP movement, probably by acting as scaffolds for the formation or breakdown of Chordin/Sog-BMP complexes. Cv2 and PGs can inhibit or promote signaling by mechanisms that are still hotly debated and that are likely to be both multiple and complex.

Although the players in hand clearly provide enough complexity to explain a range of context-dependent differences, the recent addition of several novel participants to these pathways suggests that there is more complexity to come. A question for the field is how to handle this complexity. At a minimum, we need more direct measures of the levels and localization of both individual proteins and protein-protein complexes, which is not an easy thing to achieve in vivo. Support for any model will probably rely upon simplified settings in which the activities of particular components can be isolated. Biochemical data, including additional kinetic binding parameters, are clearly crucial, and mathematical models will be increasingly important for establishing the plausibility of alternative models and for making testable predictions.

Supplementary Material

D.U. is supported by grants from the Showalter Trust and Purdue University. M.B.O. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.S.B. is supported by grants from the NIH and NSF. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Akiyama, T., Kamimura, K., Firkus, C., Takeo, S., Shimmi, O. and Nakato, H. (2008). Dally regulates Dpp morphogen gradient formation by stabilizing Dpp on the cell surface. Dev. Biol. 313, 408-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio, A. L., Taelman, V. F., Lee, H. X., Metzinger, C. A., Coffinier, C. and De Robertis, E. M. (2008). Crossveinless-2 Is a BMP feedback inhibitor that binds Chordin/BMP to regulate Xenopus embryonic patterning. Dev. Cell 15, 248-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor, H., Christ, B., Rashid-Doubell, F., Kemp, C. F., Lang, E. and Patel, K. (2002). Follistatin regulates bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) activity to stimulate embryonic muscle growth. Dev. Biol. 243, 115-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga-Solis, E., Gayraud, B., Lee, S. Y., Shum, L., Sakai, L. and Ramirez, F. (2001). Regulation of limb patterning by extracellular microfibrils. J. Cell Biol. 154, 275-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe, H. L. (2008). Type IV collagens and Dpp: positive and negative regulators of signaling. Fly (Austin) 2, 313-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe, H. L. and Briscoe, J. (2006). The interpretation of morphogen gradients. Development 133, 385-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avsian-Kretchmer, O. and Hsueh, A. J. (2004). Comparative genomic analysis of the eight-membered ring cystine knot-containing bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt, J. L., Zhang, Y., Samad, T. A., Xia, Y., Tang, J., Campagna, J. A., Schneyer, A. L., Woolf, C. J. and Lin, H. Y. (2005). Repulsive guidance molecule (RGMa), a DRAGON homologue, is a bone morphogenetic protein co-receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29820-29827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans, W. and Van Hul, W. (2002). Extracellular regulation of BMP signaling in vertebrates: a cocktail of modulators. Dev. Biol. 250, 231-250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnam, K., Murray, S. S. and Brochmann, E. J. (2006). BMP stimulation of alkaline phosphatase activity in pluripotent mouse C2C12 cells is inhibited by dermatopontin, one of the most abundant low molecular weight proteins in demineralized bone matrix. Connect. Tissue Res. 47, 271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenkaya, T. Y., Han, C., Yan, D., Opoka, R. J., Khodoun, M., Liu, H. and Lin, X. (2004). Drosophila Dpp morphogen movement is independent of dynamin-mediated endocytosis but regulated by the glypican members of heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cell 119, 231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi, D., Shilo, B. Z., Fainsod, A. and Barkai, N. (2008). Scaling of the BMP activation gradient in Xenopus embryos. Nature 453, 1205-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnerts, M. E., Wen, X., Cante-Barrett, K., Bright, J., Chen, H. T., Asundi, V., Sattari, P., Tang, T., Boyle, B., Funk, W. et al. (2004). Human Crossveinless-2 is a novel inhibitor of bone morphogenetic proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315, 272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornemann, D. J., Duncan, J. E., Staatz, W., Selleck, S. and Warrior, R. (2004). Abrogation of heparan sulfate synthesis in Drosophila disrupts the Wingless, Hedgehog and Decapentaplegic signaling pathways. Development 131, 1927-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornemann, D. J., Park, S., Phin, S. and Warrior, R. (2008). A translational block to HSPG synthesis permits BMP signaling in the early Drosophila embryo. Development 135, 1039-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochmann, E. J., Behnam, K. and Murray, S. S. (2009). Bone morphogenetic protein-2 activity is regulated by secreted phosphoprotein-24 kd, an extracellular pseudoreceptor, the gene for which maps to a region of the human genome important for bone quality. Metabolism 58, 644-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier, C., Ketpura, N., Tran, U., Geissert, D. and De Robertis, E. M. (2002). Mouse Crossveinless-2 is the vertebrate homolog of a Drosophila extracellular regulator of BMP signaling. Mech. Dev. 119Suppl. 1, S179-S184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles, E., Christiansen, J., Economou, A., Bronner-Fraser, M. and Wilkinson, D. G. (2004). A vertebrate crossveinless 2 homologue modulates BMP activity and neural crest cell migration. Development 131, 5309-5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley, C. A., Silburn, R., Singer, M. A., Ralston, A., Rohwer-Nutter, D., Olson, D. J., Gelbart, W. and Blair, S. S. (2000). Crossveinless 2 contains cysteine-rich domains and is required for high levels of BMP-like activity during the formation of the cross veins in Drosophila. Development 127, 3947-3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, C. M., Jiang, X., Hsu, T., Soo, C., Zhang, B., Wang, J. Z., Kuroda, S., Wu, B., Zhang, Z., Zhang, X. et al. (2007). Synergistic effects of Nell-1 and BMP-2 on the osteogenic differentiation of myoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 918-930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis, E. M. (2006). Spemann's organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 296-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis, E. M. (2008). Evo-devo: variations on ancestral themes. Cell 132, 185-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis, E. M. and Sasai, Y. (1996). A common plan for dorsoventral patterning in Bilateria. Nature 380, 37-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, S. and Gurdon, J. B. (1998). The interpretation of position in a morphogen gradient as revealed by occupancy of activin receptors. Cell 93, 557-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar, A. and Barkai, N. (2005). Interpreting clone-mediated perturbations of morphogen profiles. Dev. Biol. 278, 203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldar, A., Dorfman, R., Weiss, D., Ashe, H., Shilo, B. Z. and Barkai, N. (2002). Robustness of the BMP morphogen gradient in Drosophila embryonic patterning. Nature 419, 304-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entchev, E. V., Schwabedissen, A. and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. (2000). Gradient formation of the TGF-beta homolog Dpp. Cell 103, 981-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esko, J. D. and Selleck, S. B. (2002). Order out of chaos: assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 435-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterberg, R. and Fritz, A. (2009). dlx3b/4b are required for the formation of the preplacodal region and otic placode through local modulation of BMP activity. Dev. Biol. 325, 189-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster, C., Panakova, D., Mahmoud, A. and Eaton, S. (2007). Lipoprotein-heparan sulfate interactions in the hh pathway. Dev. Cell 13, 57-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmus, J., Capurro, M. and Rast, J. (2008). Glypicans. Genome Biol. 9, 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M. C., Li, Y., Seghatoleslami, M. R., Dealy, C. N. and Kosher, R. A. (2006). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans including syndecan-3 modulate BMP activity during limb cartilage differentiation. Matrix Biol. 25, 27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois, V., Solloway, M., O'Neill, J. W., Emery, J. and Bier, E. (1994). Dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo depends on a putative negative growth factor encoded by the short gastrulation gene. Genes Dev. 8, 2602-2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujise, M., Izumi, S., Selleck, S. B. and Nakato, H. (2001). Regulation of dally, an integral membrane proteoglycan, and its function during adult sensory organ formation of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 235, 433-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, W. Y., Fat, K. F., Eng, C. K. and Lau, C. K. (2007). crm-1 facilitates BMP signaling to control body size in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 311, 95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallet, A., Staccini-Lavenant, L. and Therond, P. P. (2008). Cellular trafficking of the glypican Dally-like is required for full-strength Hedgehog signaling and wingless transcytosis. Dev. Cell 14, 712-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Abreu, J., Coffinier, C., Larrain, J., Oelgeschlager, M. and De Robertis, E. M. (2002). Chordin-like CR domains and the regulation of evolutionarily conserved extracellular signaling systems. Gene 287, 39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzerro, E. and Canalis, E. (2006). Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 7, 51-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, G., Hopkins, D. R., Ho, W. B. and Greenspan, D. S. (2005). GDF11 forms a bone morphogenetic protein 1-activated latent complex that can modulate nerve growth factor-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5846-5858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlitz, O. and Basler, K. (2002). Wingful, an extracellular feedback inhibitor of Wingless. Genes Dev. 16, 1055-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez, A. J., Copley, R. R. and Cohen, S. M. (2002). HSPG modification by the secreted enzyme Notum shapes the Wingless morphogen gradient. Dev. Cell 2, 667-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsi, B. and Stringer, S. E. (2007). Tinkering with heparan sulfate sulfation to steer development. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasberger, B., Minton, A. P., DeLisi, C. and Metzger, H. (1986). Interaction between proteins localized in membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 6258-6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, K. E., Ono, R. N., Charbonneau, N. L., Kuo, C. L., Keene, D. R., Bachinger, H. P. and Sakai, L. Y. (2005). The prodomain of BMP-7 targets the BMP-7 complex to the extracellular matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27970-27980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumienny, T. L., MacNeil, L. T., Wang, H., de Bono, M., Wrana, J. L. and Padgett, R. W. (2007). Glypican LON-2 is a conserved negative regulator of BMP-like signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 17, 159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada, K., Ogai, A., Takahashi, T., Kitakaze, M., Matsubara, H. and Oh, H. (2008). Crossveinless-2 controls bone morphogenetic protein signaling during early cardiomyocyte differentiation in P19 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26705-26713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta, T., Konishi, H., Katoh, E., Natsume, T., Ueno, N., Kobayashi, Y. and Yamazaki, T. (2000). Identification of the ligand-binding site of the BMP type IA receptor for BMP-4. Biopolymers 55, 399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke, J., Wehofsits, L., Zhou, Q., Zoeller, C., Baar, K. M., Helbing, T., Laib, A., Augustin, H., Bode, C., Patterson, C. et al. (2008). BMPER is an endothelial cell regulator and controls bone morphogenetic protein-4-dependent angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 103, 804-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holley, S. A. and Ferguson, E. L. (1997). Fish are like flies are like frogs: conservation of dorsal-ventral patterning mechanisms. BioEssays 19, 281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufnagel, L., Kreuger, J., Cohen, S. M. and Shraiman, B. I. (2006). On the role of glypicans in the process of morphogen gradient formation. Dev. Biol. 300, 512-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanes, M. and Belmonte, J. C. (2008). Theoretical and experimental approaches to understand morphogen gradients. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iber, D. and Gaglia, G. (2007). The mechanism of sudden stripe formation during dorso-ventral patterning in Drosophila. J. Math. Biol. 54, 179-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iemura, S., Yamamoto, T. S., Takagi, C., Uchiyama, H., Natsume, T., Shimasaki, S., Sugino, H. and Ueno, N. (1998). Direct binding of follistatin to a complex of bone-morphogenetic protein and its receptor inhibits ventral and epidermal cell fates in early Xenopus embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9337-9932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya, M., Kawada, M., Kiyonari, H., Sasai, N., Nakao, K., Furuta, Y. and Sasai, Y. (2006). Essential pro-Bmp roles of crossveinless 2 in mouse organogenesis. Development 133, 4463-4473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya, M., Nosaka, T., Fukushima, K., Kawada, M., Furuta, Y., Kitamura, T. and Sasai, Y. (2008). Twisted gastrulation mutation suppresses skeletal defect phenotypes in Crossveinless 2 mutant mice. Mech. Dev. 125, 832-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata, H., Haraguchi, T. and Sasai, Y. (2008). Robust stability of the embryonic axial pattern requires a secreted scaffold for chordin degradation. Cell 134, 854-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja, R., Allen, B. L., Pappano, W. N., Rapraeger, A. C. and Greenspan, D. S. (2004). Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans potentiate chordin antagonism of bone morphogenetic protein signaling and are necessary for cellular uptake of chordin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51289-51297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlem, P. and Newfeld, S. J. (2009). Informatics approaches to understanding TGFβ pathway regulation. Development 136, 3729-3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura, M., Matsumoto, K., Koshiba-Takeuchi, K. and Ogura, T. (2004). Vertebrate crossveinless 2 is secreted and acts as an extracellular modulator of the BMP signaling cascade. Dev. Dyn. 230, 434-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanomata, K., Kokabu, S., Nojima, J., Fukuda, T. and Katagiri, T. (2009). DRAGON, a GPI-anchored membrane protein, inhibits BMP signaling in C2C12 myoblasts. Genes Cells 14, 695-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R., Ren, R., Pi, X., Wu, Y., Moreno, I., Willis, M., Moser, M., Ross, M., Podkowa, M., Attisano, L. et al. (2009). A concentration-dependent endocytic trap and sink mechanism converts Bmper from an activator to an inhibitor of Bmp signaling. J. Cell Biol. 184, 597-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerszberg, M. and Wolpert, L. (1998). Mechanisms for positional signalling by morphogen transport: a theoretical study. J. Theor. Biol. 191, 103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodenko, B. N., Hoek, J. B. and Westerhoff, H. V. (2000). Why cytoplasmic signalling proteins should be recruited to cell membranes. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kicheva, A., Pantazis, P., Bollenbach, T., Kalaidzidis, Y., Bittig, T., Julicher, F. and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. (2007). Kinetics of morphogen gradient formation. Science 315, 521-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelman, D. and Pyati, U. J. (2005). Bmp signaling: turning a half into a whole. Cell 123, 982-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinna, G., Kolle, G., Carter, A., Key, B., Lieschke, G. J., Perkins, A. and Little, M. H. (2006). Knockdown of zebrafish crim1 results in a bent tail phenotype with defects in somite and vascular development. Mech. Dev. 123, 277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, K. C., Townsend, T. A., Bruinsma, M. W., Barnett, J. V. and Blobe, G. C. (2008). Bone morphogenetic proteins signal through the transforming growth factor-beta type III receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7628-7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, C. A. and Selleck, S. B. (2007). Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1829-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, C. A., Knox, S. M., Staatz, W. D., Fox, B., Lercher, D. M. and Selleck, S. B. (2006). The function of a Drosophila glypican does not depend entirely on heparan sulfate modification. Dev. Biol. 300, 570-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, T., Nickel, J. and Sebald, W. (2000). BMP-2 antagonists emerge from alterations in the low-affinity binding epitope for receptor BMPR-II. EMBO J. 19, 3314-3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger, J., Perez, L., Giraldez, A. J. and Cohen, S. M. (2004). Opposing activities of Dally-like glypican at high and low levels of Wingless morphogen activity. Dev. Cell 7, 503-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, K., Pantazis, P., Bollenbach, T., Julicher, F. and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M. (2004). Dpp gradient formation by dynamin-dependent endocytosis: receptor trafficking and the diffusion model. Development 131, 4843-4856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, A. D. (2007). Morpheus unbound: reimagining the morphogen gradient. Cell 128, 245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, A. D., Nie, Q. and Wan, F. Y. (2002). Do morphogen gradients arise by diffusion? Dev. Cell 2, 785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]