Abstract

Using data from grandparents (G1), parents (G2), and children (G3), this study examined continuity in parental monitoring, harsh discipline, and child externalizing behavior across generations, and the contribution of parenting practices and parental drug use to intergenerational continuity in child externalizing behavior. Structural equation and path modeling of prospective, longitudinal data from 808 G2 participants, their G1 parents, and their school-aged G3 children (n = 136) showed that parental monitoring and harsh discipline demonstrated continuity from G1 to G2. Externalizing behavior demonstrated continuity from G2 to G3. Continuity in parenting practices did not explain the intergenerational continuity in externalizing behavior. Rather, G2 adolescent externalizing behavior predicted their adult substance use, which was associated with G3 externalizing behavior. A small indirect effect of G1 harsh parenting on G3 was observed. Interparental abuse and socidemographic risk were included as controls, but did not explain the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Results highlight the need for preventive interventions aimed at breaking intergenerational cycles in poor parenting practices. More research is required to identify parental mechanisms influencing the continuity of externalizing behavior across generations.

Keywords: externalizing behavior, intergenerational, monitoring, harsh discipline, parenting

Child and adolescent externalizing behavior, characterized by poor impulse control and oppositional, aggressive, or delinquent behavior, is associated with a wide range of negative consequences, including later substance use (Englund, Egeland, Oliva, & Collins, 2008; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992), poor academic outcomes (Masten et al., 2005; McLeod & Kaiser, 2004), and criminality (Nagin & Tremblay, 1999). In addition, externalizing behavior in one generation often is associated with externalizing behavior in the subsequent generation (Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2006; Smith & Farrington, 2004; Thornberry, Freeman-Gallant, Lizotte, Krohn, & Smith, 2003), suggesting that associated negative consequences also may echo across generations. Parenting practices, such as harsh discipline and parental monitoring, have been linked repeatedly to child externalizing behavior (Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, 2003; Gershoff, 2002; Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Stanger, Dumenci, Kamon, & Burstein, 2004), and show evidence of continuity across generations (Capaldi, Pears, Patterson, & Owen, 2003; Conger, Neppl, Kim, & Scaramella, 2003; Hops, Davis, Leve, & Sheeber, 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003). It is possible, then, that continuity in parenting practices may contribute to continuity in child externalizing behavior and that interrupting this continuity may reduce transmission of associated negative consequences. The present analyses use data from two longitudinal studies linking three generations to examine the roles of parental monitoring and harsh discipline in the intergenerational transmission of child externalizing behavior.

Theoretical Background

The Social Development Model (SDM; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) identifies socialization processes that lead to both pro- and antisocial behavior across the lifespan. The model integrates social control (Hirschi, 1969), social learning (Akers, 1977; Bandura, 1977), and differential association theories (Sutherland & Cressey, 1970), and posits key processes that may lead to antisocial or externalizing behavior, including opportunities for antisocial behavior, inappropriate or absent costs for involvement in antisocial behavior, bonding to others who engage in antisocial behavior, acceptance of beliefs that support antisocial behavior, and the lack of external constraints against such behavior (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). These socialization processes can occur in multiple areas, including family, school, and peer contexts.

The present study focuses on the provision of inappropriate costs for misbehavior (harsh discipline) and inadequate external constraints on behavior (poor parental monitoring) in the family context. According to the SDM, parental monitoring reduces children’s externalizing behavior by reducing the child’s opportunity to engage in such behavior and by increasing the probability that it will be detected (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). Empirical evidence supports the importance of parental monitoring as a predictor of a wide range of child risk behaviors (Capaldi, Stoolmiller, Clark, & Owen, 2002; Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Hawkins et al., 1992; Laird, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2003), including externalizing behavior (Beyers et al., 2003; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Stanger et al., 2004), across childhood and adolescence.

Harsh discipline, here defined as spanking, threatening, yelling, or screaming in response to misbehavior, is thought to contribute to higher levels of child externalizing behavior by promoting norms supportive of violence or aggression (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). Associations between harsh discipline and child externalizing behavior from early childhood to adolescence have been demonstrated (Gershoff, 2002; Leve et al., 2005; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008; Nix et al., 1999).

The SDM predicts intergenerational continuity in both externalizing behavior and parenting practices. Continuity in externalizing behavior is expected because parents who engaged in externalizing behavior when they were young are hypothesized to continue such behavior in adulthood, to associate with others who behave similarly, and to hold norms and beliefs that favor antisocial behavior (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). Thus, their children are thought to be at increased risk for exposure to antisocial opportunities from their parents or their parents’ friends, formation of affective bonds to antisocial others, and adoption of norms and beliefs that promote antisocial behavior. Further, parents who hold antisocial norms are expected to provide fewer external constraints on their children and to resort to poor discipline practices. Continuity in parenting practices is expected because it is hypothesized that adult parents (G2) will have internalized the norms and beliefs about parenting that they experienced as children. Further, continued involvement with and bonding to their own parents (G1) is expected to contribute to shared norms and similarity in parenting practices (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985).

Intergenerational Transmission of Parenting Practices and Externalizing behavior

A small body of studies demonstrates continuity in parenting practices across generations in prospective, multigenerational samples (Capaldi et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004; Thornberry et al., 2003). Specifically, intergenerational transmission of harsh and aggressive parenting (Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Scaramella & Conger, 2003) and parental monitoring (Smith & Farrington, 2004) has been shown. Other studies have shown continuity in consistent discipline and parental warmth (Thornberry et al., 2003), and in parenting practices constructs that include harsh parenting (Capaldi, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2008; Capaldi et al., 2003) and parental monitoring (Capaldi et al., 2003). Several of these authors draw heavily from theories that, similar to the SDM, focus on modeling and aspects of social learning as key mechanisms for intergenerational continuity in parenting practices (e.g., Capaldi et al., 2003; Scaramella & Conger, 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003). Results from these studies consistently support intergenerational continuity across multiple aspects of parenting.

Findings from multigenerational studies of the transmission of externalizing behavior across generations are mixed. Two studies have linked parent (G2) antisocial behavior measured in adolescence and later externalizing behavior (Thornberry et al., 2003) or difficult temperament (Capaldi et al., 2003) among their G3 children. Other studies, however, have not found associations between G2 and G3 antisocial behavior (Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003), or have found associations between G2 adult – but not child or adolescent – antisocial behavior and concurrent conduct problems in G3 (Smith & Farrington, 2004). Inclusion of small numbers of participants (e.g., Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003) and the use of different measures to capture G2 and G3 antisocial behavior (e.g., criminality in G2 and externalizing in G3) may help to explain the inconsistency in the literature.

Given that parenting practices are linked both theoretically and empirically to child externalizing behavior, it is plausible that continuity in parenting practices may contribute to cross-generation resemblance in externalizing behavior. We found five prior studies that have tested this hypothesis in three-generation samples (Capaldi et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004; Thornberry et al., 2003). Findings as to whether parenting constitutes a mechanism for continuity in antisocial behavior from G2 to G3 are mixed. Two studies found evidence that G2 adolescent antisocial behavior was associated with their later poor parenting, which was, in turn, predictive of higher levels of G3 externalizing as measured by the CBC (Hops et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003). This pathway partially mediated the association between G2 adolescent antisocial behavior and G3 externalizing in one of those studies (Thornberry et al., 2003). In the Hops and colleagues study, there was no association between G2 adolescent aggression and G3 externalizing. Another study found no evidence of intergenerational continuity in externalizing behavior and no association between G2 adolescent aggression and their later parenting of G3 (Conger et al., 2003). In the Capaldi and colleagues study (Capaldi et al., 2003), continuity in parenting from G1 to G2 was significant when considered alone, but when a pathway from G2 adolescent antisocial behavior to their parenting of G3 was included in the model, neither pathway met conventional levels of significance. The final study (Smith & Farrington, 2004) found evidence for continuity in monitoring from G1 to G2. Although poor parental monitoring was associated with child externalizing behavior in the G1–G2 pair, poor G2 monitoring of G3 was not associated with G3 externalizing behavior. These authors did not test whether G2 adolescent delinquency predicted their later poor monitoring of G3.

Alternative Explanations for Continuity in Externalizing Behavior

A number of plausible alternative mechanisms for continuity in externalizing behavior and parenting practices exist, including parent substance use (Bailey et al., 2006; Pears, Capaldi, & Owen, 2007), family violence (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004), and sociodemographic risk (Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, & Wu, 1991; Thornberry et al., 2003). All of these variables have been associated with child externalizing behavior (Bailey et al., 2006; Buehler et al., 1997; Hinshaw, 2002; Schuckit et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004; Stanger et al., 2004) and have demonstrated intergenerational continuity (Chassin, Pitts, DeLucia, & Todd, 1999; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Johnson & Leff, 1999; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2005; Musick & Mare, 2006; Thornberry et al., 2003). Therefore, parent substance use, IPA, and sociodemographic risk are included here as competing processes that may explain observed continuity in externalizing behavior, parental monitoring, and harsh parenting.

The Present Study

The present study builds on prior work with multigenerational samples by examining parental monitoring and harsh parenting as potential mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior, by including tests of potential competing mechanisms, and by modeling G3 age. Examining parental monitoring and harsh parenting independently reflects the theoretically distinct mechanisms thought to be at work, namely the imposition of external constraints (monitoring) expected to reduce externalizing behavior and the provision of inappropriate costs for undesired behavior (harsh parenting) expected to increase externalizing behavior. Examining these variables independently also enables identification of clear intervention targets by highlighting specific parent behaviors that may be influential. Measures of sociodemographic risk, interparental conflict, and parent substance use are included as alternative mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Because G2 adolescents with externalizing problems may have children at younger ages (Miller-Johnson et al., 1999) and because G3 age may be associated with their levels of externalizing behavior (Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008), inclusion of G3 age in the model is important. The same measure of externalizing behavior – teacher reports from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBC; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001)– is used in both G2 and G3. Finally, although some prior studies reported zero-order associations between G1 parenting and G3 externalizing behavior (Capaldi et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003), none report multivariate statistical tests of indirect effects of G1 parenting practices on G3 externalizing behavior.

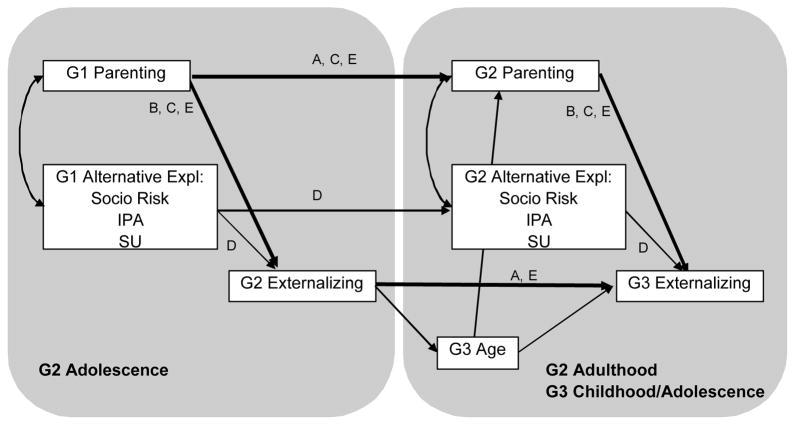

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model underlying this study and highlights hypothesized causal paths and mediated relationships. Based on predictions about the effects of external constraints, modeling, and acceptance of norms favoring antisocial behavior in the SDM, we expect that: (a) both parenting practices and child externalizing behavior will show continuity across generations; (b) poor parental monitoring and harsh parenting will predict higher levels of child externalizing behavior in both generations; and (c) intergenerational continuity in poor parenting practices may explain continuity in child externalizing behavior. Alternately, (d) continuity in parent substance use, IPA, or sociodemographic risk may explain the cross-generation transmission of externalizing behavior. Finally, (e) grandparent parenting practices may affect the externalizing behavior of their grandchildren indirectly via higher levels of G2 externalizing behavior or poor G2 parenting.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Letters correspond to study hypotheses A, B, C, D and E, and designate pathways implicated in each hypothesis.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The present analyses draw data from two closely related research projects: the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and The Intergenerational Project (TIP). SSDP is a longitudinal study of youth development and pro- and antisocial behavior. Participants were recruited from 18 Seattle public elementary schools that primarily served higher risk neighborhoods. From the population of 1,053 students entering Grade 5 (age 10) in participating schools in the fall of 1985, 808 students (77% of the population) consented to participate in the longitudinal study and constitute the SSDP sample. Interviews were conducted yearly from ages 10 to 16, at age 18, and every 3 years thereafter, including age 27. Data were obtained through the administration of parent (G1) and student (G2) questionnaires. G2 interviews were conducted in English in person, and were administered by trained interviewers. G1 interviews were administered over the telephone. When respondents did not have a telephone or when their number was unlisted0, in-person interviews were conducted (O’Donnell, Hawkins, & Abbott, 1995). It is unknown what language was spoken in the G1–G2 home. Only G2 surveys were administered from age 18 onwards.

Ninety-five percent (n = 771) of G1 parents completed at least one of the seventh-and eighth-grade (G2 ages 13 and 14) interviews. At the interview administered when G2 were age 13, 86% of G1 parents were mothers or acting as mothers. According to G2 reports, mothers averaged 39 years of age (range 26 to 66 years). About 9% of G1 parents were fathers or acting as fathers. According to G2 reports, fathers averaged 42 years of age (range 26 to 74 years). The remaining 5% of G1 “parents” were other adults acting as parents. The age of these other adults is unknown.

About 81% of the original 808 G2 participants completed the age 13 interview, and 96% completed the age 14 interview. Ninety-two percent of the original 808 G2 participants completed the age 27 interview. Nonparticipation at each assessment was not consistently related to ethnicity or alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other illicit drug use by age 10. At age 27, slightly more women than men participated (94.7% vs. 90.3%), however, this was explained by higher rates of death among male participants (3% versus 1% for women), and likely not attributable to a differential willingness to participate. These 808 participants constitute the available sample for analyses of the association between G1 parenting practices and G2 externalizing behavior.

In 2002, TIP began data collection on G2 SSDP participants and their children (G3). TIP is a longitudinal study following consenting G2 SSDP participants raising children of their own to examine the consequences of parental and grandparental substance use on child development. SSDP sample members were invited to participate in TIP if they had a biological child with whom they had face-to-face contact, at minimum, on a monthly basis. In cases where there were multiple biological children, the oldest child was selected. First born G3 children of any age were included. TIP used an accelerated longitudinal design, in which multiple age cohorts were measured annually and new families were recruited for the study as they became parents for the first time. The present study makes use of data from the first two annual data collection waves of TIP.

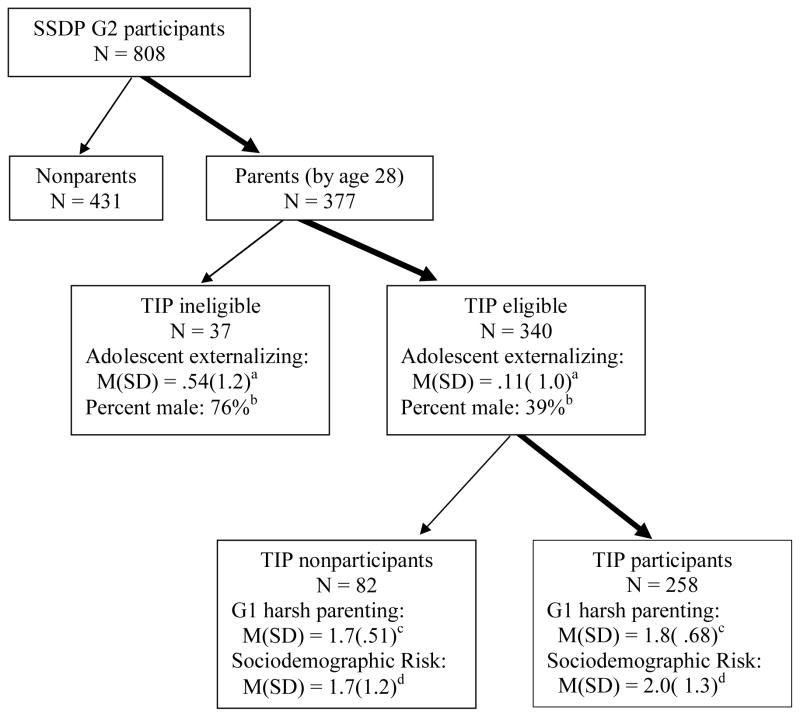

Figure 2 displays information on TIP eligibility and participation among G2 parents. There were 377 SSDP participants who reported having a biological child by the second year of TIP, of whom 340 met the eligibility criterion (face-to-face contact with the G3 child at least once per month). About 76% (n = 258) of eligible parents consented to participate in either Wave 1 or 2. Analyses of differential eligibility and participation included G1 sociodemographic risk, substance use, IPA, and harsh parenting, and G2 gender, adolescent externalizing, adult sociodemographic risk, and adult substance use. There were no significant differences between eligible and recruited participants on G1 substance use, sociodemographic risk, or interparental aggression, nor on G2 substance use in adulthood. Eligible G2 parents were rated by teachers during adolescence as having less externalizing behavior and were more likely to be female than parents who did not have sufficient contact with their child to meet eligibility requirements (Figure 2). Eligible SSDP G2 parents who chose to participate in TIP were more likely to have experienced harsh parenting by G1 and reported higher levels of sociodemographic risk in adulthood (Figure 2) compared to those who chose not to participate. Table 1 displays demographic information on grandparents, parents, and children.

Figure 2.

Eligiblity and recruitment into the TIP study. Values with the same superscript are significantly different from each other (p < .05).

Table 1.

SSDP and TIP sample demographic characteristics

| G1 Grandparents N = 771 | G2 Parents N = 258 | G3 Children N = 258 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 83% | 64% | 49% |

| African American | 22% | 23% | 20% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 18% | 10% | 8% |

| Native American | 3% | 5% | 2% |

| Caucasian | 51% | 38% | 32% |

| Multi-Racial/Other | 3% | 24% | 38% |

| Hispanic | 3% | 8% | 13% |

| Sociodemographic Risk Score | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.0) | - |

| M (SD) |

NOTE: G2 and G3 demographics are from Wave 1 of TIP. Sociodemographic risk scores range from 0 to 4. For G2 and G3, Hispanic ethnicity was not mutually exclusive with other ethnicity designations. Therefore, percentages sum to more than 100.

Parent, alternate caregiver, and child interviews were conducted in person by trained interviewers. It is unknown what language was spoken in the G2–G3 home. Interviews were timed to occur within 6 weeks of the G3 child’s birthday. In addition, questionnaires were mailed to teachers of 105 children age 6 and older in Wave 1 and to teachers of 124 children age 6 and older in Wave 2. Ninety-seven teachers (92%) returned the Wave 1 teacher survey, and 113 (91%) returned the Wave 2 survey, for a cumulative total of 136 students. Because the present analyses make use of teacher-reported child behavior problems, these 136 school-aged children (ages 6 to 14, average age 9) constitute the available sample for analyses of associations between G2 parenting and G3 externalizing behavior. The Human Subjects Review Committee at the University of Washington approved the procedures and measures used in both the SSDP and TIP studies.

Measures

Parent externalizing behavior in adolescence

When parents (G2) were ages 13 and 14, their teachers completed the Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986). Responses to individual items were averaged across the 2 years. A Conduct Disorder score was obtained by averaging the following 10 items: cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others; destroys others’ things; destroys his or her own things; gets in many fights; physically attacks people; hangs out with kids who get in trouble; runs away from home; steals; sets fires; threatens others. The internal consistency of items in the Conduct Disorder scale was good (Cronbach’s α = .89). An Attention Problems score was created by averaging the following 3 items (α = .80): restless, can’t sit still; impulsive; has trouble concentrating. An Oppositional Defiant score was obtained by averaging the following five items (α = .89): argues; disobedient at school; defiant, talks back; stubborn, sullen or irritable; has a hot temper. The use of these items and scales is consistent with work by Lengua and colleagues (2001) and by Achenbach and Rescorla (2001). SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc, 2008) and maximum likelihood estimation were used to create G2 externalizing behavior factor scores from these three scales for use in analyses. The study used teacher-reported externalizing behavior (for both G2 and G3) to reduce potential reporting bias which may result from using parent reports of both parenting practices and child behavior.

Child externalizing behavior

During the first two annual data collection waves of TIP, teachers completed the Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) about the G3 children attending school (i.e., ages 6 – 14 years, M = 9 years). Similar to the G2 externalizing behavior scales, we created Conduct Disorder (Wave 1 Cronbach’s α = .78, Wave 2 α = .86), Attention Problems (Wave 1 α = .76, Wave 2 α = .84), and Oppositional Defiant (Wave 1 α = .90, Wave 2 α = .90) scores for the G3 children. For those children who participated in both waves, their respective Conduct Disorder, Attention Problems, and Oppositional Defiant scores were averaged across waves. SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc, 2008) and maximum likelihood estimation were used to create G3 externalizing behavior factor scores from these three scales for use in analyses.

Parental monitoring

G1 monitoring of G2 was based on G1 reports obtained at two time points, when G2 were age 13 and 14. At each of these times, G1 were asked “How often do you know where your child is and who s/he is with?” Response options ranged from 1 (almost always) to 5 (almost never). Items were reverse coded, so that higher scores indicated more monitoring, and averaged across waves to create a single, measured variable.

In addition to knowing their child’s whereabouts and companions, G2 parents were asked “How often do you talk with (CHILD) about what s/he has done during the day?” and “When (CHILD) is out, how often do you know when s/he will be home?” G2 monitoring of G3 was based on G2 reports obtained in TIP years 1 and 2. Response options ranged from 1 (almost always) to 5 (almost never). Items were coded so that higher scores indicated more monitoring. When families had participated in both waves, responses to each question were averaged across waves. The three monitoring items were averaged to create a single, observed variable (α = .62).

Harsh discipline

When G2 were age 13 and 14, G1 were asked “How often do you and (CHILD) yell at each other?” and “When (CHILD) disobeys you, do you spank him/her?” Response options ranged from 1 (almost always) to 5 (almost never). Items were recoded so that higher scores reflected more harsh discipline. Responses to each question were averaged across waves, and then averaged together to create a single index of G1 harsh parenting.

During years 1 and 2 of TIP, G2 parents were asked: “In the past year, when (CHILD) misbehaved, how often did you: shout, yell, or scream at (him/her)? threaten to spank or hit (him/her), but didn’t actually do it? spank (him/her)?” Response options ranged from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always or almost always). Responses to each item were averaged across the two waves, and the resulting three items were averaged to create an index of G2 harsh discipline.

Grandparent and parent substance use

Grandparents (G1) reported on the frequency of their own and their live-in partner’s binge drinking (five or more drinks per occasion), marijuana use, and cigarette use when G2 were in seventh and eighth grades (average ages 13 & 14). Binge drinking, marijuana use, and cigarette use frequencies were averaged across partners and grades. When there was no live-in partner, only the respondent’s substance use was used. To reduce skew, frequency scores for each substance were grouped into three ordered categories: binge drinking—0 (never), 1 (once in a while), 2 (less than half of the time or more than half of the time); marijuana use—0 (never), 1 (less than once per month), 2 (2–3 times or more per month); cigarette use—0 (never or quit), 1 (less than 1 pack per day), 2 (1 pack or more per day). Parents (G2) reported on their own binge drinking (five or more drinks per occasion), marijuana use, and cigarette use at age 27. Respondents were asked how many times they had engaged in each of these behaviors during the month prior to the interview. To reduce skew, frequency variables were categorized into the following ordered categories: binge drinking and marijuana use—0 (no use), 1 (once or less per week), 2 (more than once per week); and cigarette use—0 (no use), 1 (less than 1 pack per day), 2 (1 pack or more per day). These categorical binge drinking, marijuana use, and cigarette use variables were used as indicators of latent G1 and G2 substance use constructs.

Interparental abuse

Interparental abuse was assessed in G1 and G2 using items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). G1 answered questions at two time points, when G2 were age 13 and 14. Items included “During the last year, how often have you: berated or put your spouse/partner down on purpose? yelled at your spouse/partner? threatened to hit or throw something at your spouse/partner? pushed, grabbed or shoved your spouse/partner? slapped or hit your spouse/partner?” Respondents also reported how often their partner did these things. Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 6 (>20 times). G2 reported on abuse in their romantic relationships in years 1 and 2 of TIP, when, on average, they were 27 and 28 years old. Parents were asked “How often do/did you: insult, swear, or yell at (PARTNER)? threaten to end your relationship or leave? threaten to hit (PARTNER)? push, grab, slap, or shove (PARTNER)?” Parents also were asked how often their partner did these things. Response options ranged from 1 (very often) to 5 (never). Items were recoded so that higher scores reflect more abuse. Within each generation and across waves, items tapping both victimization and perpetration were averaged to form two observed variables: G1 interparental abuse (α= .81) and G2 interparental abuse (α= .84).

Sociodemographic risk

To address the possibility that observed intergenerational relationships were due to sociodemographic differences rather than parenting, we included a measure of sociodemographic risk for both G1–G2 and G2–G3. Risks included being an unmarried parent, low education, high neighborhood disorganization (presence of crime, drug selling, gangs, violence, etc.), and poverty. Sociodemographic risk scores reflected the total number of risks experienced (range 0 to 4). Poverty for G1–G2 was indicated by G2 eligibility for the National School Lunch/School breakfast program at age 11, 12, or 13. Poverty for G2–G3 was indicated by G2 receipt of AFDC, TANF, or Food Stamps in the first year of TIP. The measure of neighborhood disorganization in the G1–G2 neighborhood was based on G2 reports of their perceived levels of neighborhood crime, drug selling, poverty, gangs, and undesirable neighbors, obtained when G2 were in eighth grade (age 14, α = .84). Neighborhood disorganization in the G2–G3 neighborhood was similarly measured using reports by G2 parents at age 27 (α = .88). Low parent education and high neighborhood disorganization were based on a median split of the sample.

Analysis

We evaluated the hypothesized relationships between G1 and G2 parenting practices and G2 and G3 externalizing behavior using Mplus Version 3.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2004). Mplus uses Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation in the presence of cases with missing data. Current methodological research on analysis in the presence of missing data suggests that FIML provides unbiased parameter estimates when some questions are not applicable to all sample members (“out-of-scope missingness,” Schafer & Graham, 2002), as is the case with G2 parenting and G3 externalizing behavior in this study, given that not all G2 participants have children. FIML was employed to utilize all available information from the larger SSDP sample (n = 808) and the smaller TIP parent (n = 258) and G3 (n = 136) samples. Specifically, parameter estimates for relationships between G1 parenting practices and G2 externalizing behavior are based only on cases where data are present for the relevant variables (n = 808). Parameter estimates for relationships between G1 parenting practices and G2 parenting practices similarly are based only on those cases where relevant data are present (n = 258 TIP parents). Finally, parameter estimates of the association between G2 parenting and G3 externalizing behavior are based only on the 136 cases where both G2 parenting and G3 externalizing behavior data are available (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2004; Schafer & Graham, 2002).1 Parameter estimates produced by FIML are unbiased with relation to any potential correlates of missingness that are included in the model (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001; Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fisk, 2003; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Thus, although TIP participants experienced slightly more harsh parenting and reported more sociodemographic risk than those who were eligible but chose not to participate, results should be unbiased with respect to these variables. Bias is still possible if missingness is related to variables that are not included in the model, however, even in this case bias is minimized using FIML compared to other methods like listwise deletion or mean substitution (Collins et al., 2001; Graham et al., 2003; Schafer & Graham, 2002).

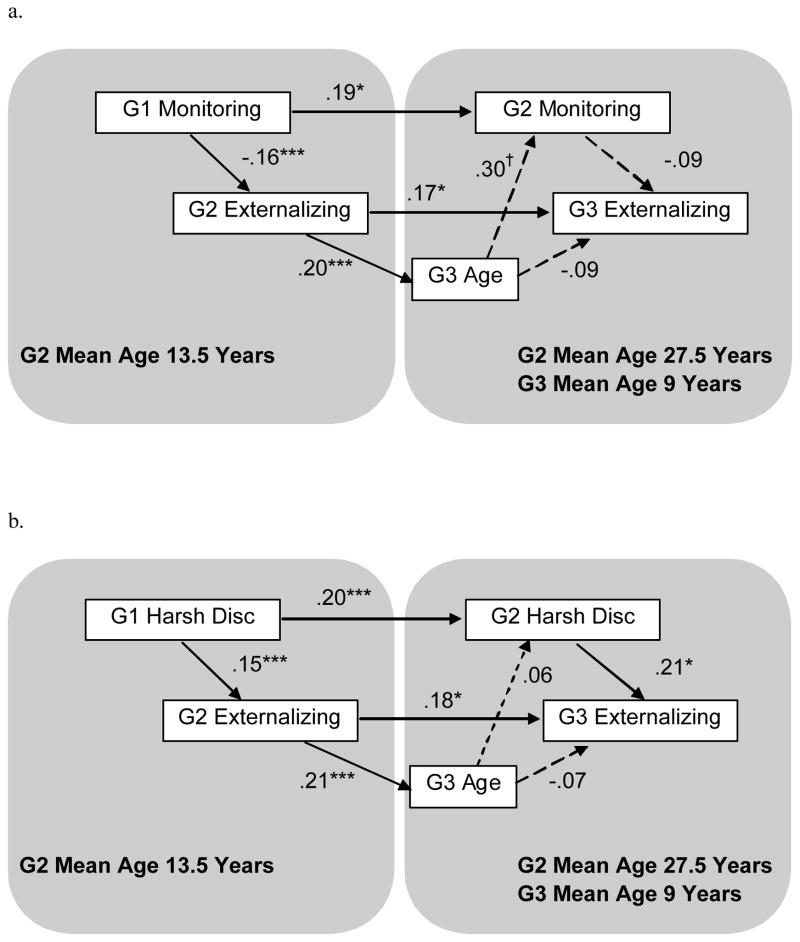

A portion of the sample was exposed to a multicomponent preventive intervention in the elementary grades, consisting of teacher training, parenting classes, and social competence training for children (Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott, & Hill, 1999). Previous analyses have shown that a “full” intervention group that received all of the intervention components and a control group of participants who received no intervention were most likely to demonstrate significant intervention effects on mean levels of behavior (Hawkins et al., 1999). Multiple group modeling analyses revealed no significant differences between the full intervention and control groups for either the harsh parenting or parental monitoring models presented in Figure 3. Therefore, the full sample was used in all analyses.

Figure 3.

Path models of intergenerational continuity in parenting practices and externalizing behavior. A. Parental monitoring model. B. Harsh discipline model. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, †p < .10.

Parameter estimates presented in the text and Figures are fully standardized, and can be interpreted as effect sizes similar to Cohen’s d. For example, a parameter estimate of. 19 between independent variable x and dependent variable y indicates that a 1 standard deviation increase in variable x is associated with a. 19 standard deviation increase in variable y (Bollen, 1989). Unstandardized parameter estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for path and structural equation models are presented in Appendix A for the convenience of interested readers and those conducting quantitative literature reviews.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 2 presents the results of bivariate correlation analyses of study variables. G2 externalizing behavior was positively associated with G3 externalizing behavior. G2 parental monitoring and harsh discipline were associated positively with respective G1 parenting practices. Cross-generation associations were significant but not large, indicating both continuity and discontinuity in parenting practices and child externalizing behavior in this sample. G2 externalizing behavior in adolescence was not related to their later parenting practices at the zero order. Parent substance use and sociodemographic risk were associated with higher levels of child externalizing behavior in both generation pairs. Exposure to IPA was associated with higher levels of adolescent externalizing behavior among G2 participants, but not among G3 participants. None of the associations between G1 variables and G3 externalizing behavior reached statistical significance in bivariate analyses, suggesting no direct influence of G1 parenting on grandchildren.

Table 2.

Zero Order Associations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G1 Monitoring | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. G1 Harsh Disc | −.17*** | - | |||||||||||

| 3. G1 Socio Risk | −.14*** | .10** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. G1 SU | −.10† | .06 | .30*** | - | |||||||||

| 5. G1 IPA | .02 | .14** | .06 | .34*** | - | ||||||||

| 6. G2 Externalizing | −.14*** | .15*** | .22*** | .24*** | .19*** | - | |||||||

| 7. G2 Monitoring | .17* | .05 | −.20* | .18 | −.19† | −.14 | - | ||||||

| 8. G2 Harsh Disc | .06 | .23*** | .05 | −.03 | .08 | .03 | .07 | - | |||||

| 9. G2 Socio Risk | −.07† | .08† | .21*** | .21*** | .17*** | .23*** | −.12 | .19** | |||||

| 10. G2 SU | −.06 | .04 | .05 | .23** | .16** | .22*** | −.37*** | .02 | .37*** | - | |||

| 11. G2 IPA | −.06 | .09 | .18** | .03 | .12 | .10 | −.20* | .29*** | .18** | .20* | - | ||

| 12. G3 Age | −.12† | .08 | .11† | .10 | .05 | .25*** | −.02 | .07 | .34*** | .09 | .03 | - | |

| 13. G3 Externalizing | −.05 | .10 | .06 | .14 | .18 | .21* | −.12 | .21* | .23** | .31** | .02 | −.03 | - |

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Path and Structural Equation Modeling

Two path models were estimated to test the first three study hypotheses (see Figure 3): (a) both parenting practices and child externalizing behavior will show continuity across generations, (b) poor parenting practices will predict child externalizing behavior in both generations, and (c) intergenerational continuity in poor parenting practices may explain continuity in child externalizing behavior. The first model (Figure 3a) included G1 and G2 monitoring, G2 and G3 externalizing behavior, and G3 age. Model fit was good [χ2(800, 3) = 1.94, p = .58, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA estimate = .00, SRMR = .02]. Significant associations were found between G1 monitoring and G2 monitoring and between G2 externalizing behavior and G3 externalizing behavior fourteen years later (hypothesis a). Within time periods, G1 monitoring was significantly associated with lower levels of G2 externalizing behavior, but the association between G2 monitoring and G3 externalizing behavior was not significant (hypothesis b). Results did not support the hypothesis that continuity in parental monitoring would explain intergenerational continuity in child externalizing behavior (hypothesis c). The parameter estimate linking G2 and G3 externalizing behavior (.17) was slightly diminished from the zero order association (r = .21), but remained statistically significant. Further, a direct path from G2 externalizing to their later monitoring of G3 was nonsignificant (not shown). Exclusion of this nonsignificant path did not significantly affect model fit. G2 externalizing behavior was positively related to G3 age, indicating that G2 participants with higher externalizing behavior scores had their children at a younger age. G3 age was not related to G3 externalizing behavior scores, but was marginally associated with G2 monitoring.

Figure 3b shows results from the harsh discipline model. Data fit the model well [χ2(801, 3) = .54, p = .91, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.2, RMSEA estimate = .00, SRMR = .01]. Harsh discipline demonstrated statistically significant continuity from G1 to G2 (hypothesis a), and was associated with higher levels of child externalizing behavior in both generation pairs (hypothesis b). Results were not consistent with the hypothesis that G1 – G2 continuity in harsh discipline would explain the observed intergenerational continuity in child externalizing behavior (hypothesis c). As in the parental monitoring model, the parameter estimate linking G2 and G3 externalizing behavior (.18) was somewhat reduced from the zero order relationship (r = .21), but remained statistically significant. Omission of a nonsignificant direct path from G2 adolescent externalizing to later G2 harsh parenting did not adversely affect model fit. G2 externalizing behavior was positively related to G3 age and G3 externalizing behavior. G3 age was not associated with either G2 harsh discipline or G3 externalizing behavior.

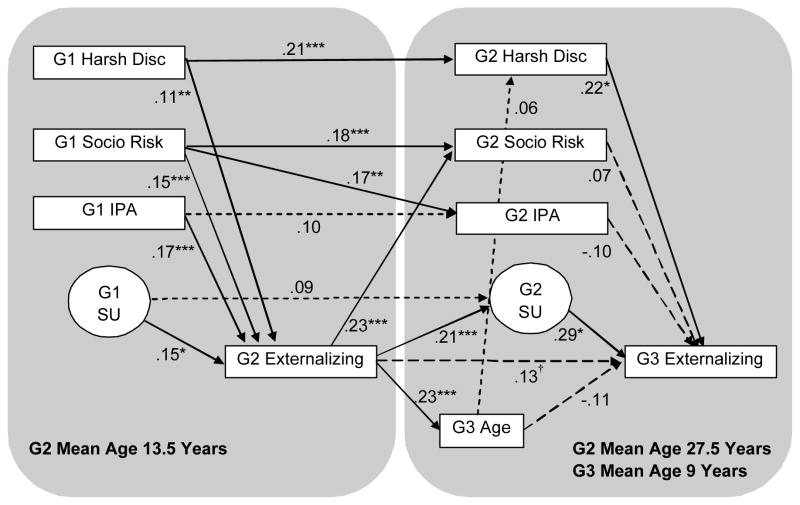

To test the alternate hypothesis that intergenerational continuity in parent substance use, interparental abuse (IPA), or sociodemographic risk would explain the cross-generation transmission of child externalizing behavior (hypothesis d), the structural equation model in Figure 4 was estimated. Model fit was adequate [χ2(808, 47) = 62.22, p = .07, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA estimate = .02, WRMR = .73]. Because the substance use measures combined three separate constructs (binge drinking, cigarette use, and marijuana use), they were modeled as latent factors. Indicators of the latent G1 and G2 substance use constructs loaded significantly on their respective factors, and loadings ranged from .44 to .75. Because G2 parental monitoring was not significantly related to G3 externalizing behavior in earlier analyses, only harsh parenting was included in the final model. Results showed that, in the presence of alternate explanatory variables, G1 harsh parenting continued to predict G2 harsh parenting, and harsh parenting continued to demonstrate positive associations with child externalizing behavior in both generation pairs (hypotheses a and b). Sociodemographic risk also showed evidence of continuity from G1 to G2, but substance use and IPA did not. Consistent with prior findings from this sample (Bailey et al., 2006), G1 substance use was, however, related to G2 adolescent externalizing behavior, which was, in turn, related to G2 adult substance use. G2 adult substance use was associated with higher levels of G3 externalizing behavior (hypothesis d). Sociodemographic risk and IPA were related to child externalizing behavior for G1 – G2, but not for G2 – G3. The inclusion of parent substance use, IPA, and sociodemographic risk in the model reduced the size of the association between G2 and G3 externalizing behavior and rendered it nonsignificant (standardized parameter estimate = .13, hypothesis d).

Figure 4.

Final model. Intercorrelations among G1 Substance Use (SU), G1 IPA, G1 Sociodemographic Risk, and G1 Harsh Discipline were specified in the statistical model, but are not shown to improve readability of the figure. Intercorrelations among G2 Substance Use (SU), G2 IPA, G2 Sociodemographic Risk, and G2 Harsh Discipline and between G3 Age and G2 Sociodemographic Risk were specified in the statistical model, but also are not shown. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, †p < .10.

To test our final hypothesis, that poor parenting by G1 may be associated indirectly with higher levels of externalizing behavior in their grandchildren (G3), we used the MODEL INDIRECT feature available in Mplus to test for a significant, overall indirect relationship between G1 harsh parenting and G3 externalizing behavior in the full model (Figure 4). Results showed a small, but statistically significant total indirect effect [standardized parameter estimate .07, unstandardized estimate (95% CI) .10 (.02 – .17)], which operated via a specific indirect effect linking G1 harsh discipline to G2 harsh discipline to G3 externalizing behavior.

Discussion

This study examined parenting practices (parental monitoring and harsh discipline) and drug use as mechanisms in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. It built on existing multigenerational studies by examining both parental monitoring and harsh parenting practices, by including tests of potential competing mechanisms, and by accounting for G3 age. Findings suggest that both parenting practices and child externalizing behavior showed intergenerational continuity. Results partially supported the hypothesis that parental monitoring and harsh discipline would be associated with child externalizing in both generation pairs. Both G1 parenting practices were associated with G2 adolescent externalizing behavior, but only harsh parenting by G2 was associated with G3 externalizing. These parenting practices did not appear to mediate the relationship between G2 and G3 externalizing behavior (hypothesis c). Rather, results suggest that G2 externalizing behavior in adolescence was associated with later G2 substance use in adulthood, which, in turn, predicted G3 externalizing (hypothesis d). Our final hypothesis, that grandparent parenting practices may be associated indirectly with grandchild externalizing behavior via higher levels of parent externalizing behavior or poor parenting practices, was supported. Results showed a significant but weak indirect association between G1 harsh parenting and G3 externalizing via higher levels of G2 harsh parenting.

The finding of significant associations between G1 monitoring and G2 monitoring, and between G1 harsh discipline and G2 harsh discipline in this study are in line with a growing body of research demonstrating continuity in parenting practices across generations using prospective data (Capaldi et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003). As with other prior studies, however, we found that the degree of continuity in parenting practices was small (standardized parameter estimates ~ .20), indicating that there was also a good deal of discontinuity across generations. Under the Social Development Model (SDM), this is to be expected, given that G2 parents may be bonded to and share norms about parenting with G1 to some extent (contributing to continuity), but also that the socialization experiences of G2 parents were likely different from those of G1 parents (contributing to discontinuity). Future research on intergenerational transmission of parenting practices also should investigate mechanisms of discontinuity. For example, research by Capaldi and colleagues (Capaldi et al., 2008) highlights the role of the G2 parent’s partner in influencing G2 parenting practices, which may contribute to discontinuity between G1 and G2 parenting practices. Other researchers have found that intergenerational continuity in hostile parenting from G1 to G2 was observed only when G3 children demonstrated high negative reactivity, which was thought to elicit or condition hostile parenting by G2 parents (Scaramella & Conger, 2003). Examination of other potential influences on G2 parenting and of moderators that may interrupt or facilitate G1–G2 continuity in parenting practices is critical to a more complete understanding of the intergenerational transmission of parenting.

We found a small but significant association between G2 externalizing behavior at ages 13–14 and the later externalizing behavior of their G3 children at ages 6–14 (mean age 9). This finding is consistent with SDM theory and some prior research demonstrating parent-child continuity in externalizing behavior (Capaldi et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003). An advantage of coupling the SSDP data with the TIP data was that the same measure – teacher-reported externalizing based on the CBC – was available for both G2 and G3, although measures were not taken at the same ages for both generations. This may have contributed to the finding of intergenerational continuity, and may help to explain the differences between the present results and prior research that did not demonstrate continuity (Conger et al., 2003; Hops et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004). Future multigenerational research should continue to investigate continuity in antisocial behavior to clarify the degree to which it is carried across generations. Further investigation as to the continuity of age at onset and developmental patterns of antisocial behavior across time also would be useful. Larger sample sizes and similar measurement across generations may help to resolve these questions. The present results, taken with those from other studies finding intergenerational continuity in externalizing behavior, however, suggest that the degree of continuity is small. Therefore, future research also should examine mechanisms of discontinuity, including moderators that may buffer or facilitate the transmission of externalizing behavior.

Evidence from this study as to the association between parenting practices and child externalizing behavior was mixed. As expected, harsh discipline was associated with child externalizing behavior in both generation pairs. According to the SDM, this may be because harsh discipline communicates norms favoring aggressive and hostile behavior that are then adopted by children (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). Contrary to expectations, however, parental monitoring was not associated with child externalizing behavior in both generations; only the association between G1 monitoring and G2 externalizing reached statistical significance. This finding echoes that of Smith and Farrington (2004), who found a similar pattern of results. Several possible explanations for this discrepancy between the hypothesized relationship and the results exist. Prior research indicates that the strength of the relationship between parental monitoring and externalizing behavior may vary with child age (Frick, Christian, & Wootton, 1999), such that monitoring is more strongly associated with externalizing behavior in late childhood and adolescence, but only weakly related in children aged 6–9. Thus, it may be that the inclusion of G3s spanning ages 6–14 in this study (and 3–15 in the Smith and Farrington study) resulted in an attenuation of the relationship between G2 monitoring and G3 externalizing, in spite of the inclusion of G3 age in the model. Alternatively, it may be that the measures of monitoring used here, which focused on times when the parent and child were apart, were more appropriate to older children. Supporting this notion, there was little variance in measures of G2 monitoring of G3 in the present study, and the mean level of monitoring reported was quite high, indicating a possible ceiling effect. Future multigenerational studies should explore ways to measure parental monitoring among younger children and in samples of children that vary widely in age.

Results from this study did not support the hypothesis that continuity in parenting practices explains the association between G2 externalizing behavior and G3 externalizing behavior. Although parenting practices were mostly related to child externalizing in this study, inclusion of G1 and G2 parenting practices in statistical models did not eliminate the significant association between G2 and G3 externalizing. Nor was G2 externalizing in adolescence related to their later parenting of G3. What did appear to explain the observed continuity in externalizing behavior across generations was G2 substance use in adulthood; G2 adolescent externalizing predicted their adult substance use, which was associated with G3 externalizing. It may be that other parenting practices (e.g., family management) or parent-child relationship characteristics (e.g., bonding) mediate these relationships.

Finally, although we did not observe significant zero-order associations between G1 parenting practices and G3 externalizing, we did observe a significant, overall indirect effect of G1 harsh discipline on G3 externalizing. It is logical that past grandparent parenting practices may affect the development of their grandchildren indirectly by influencing G2 parenting practices, problem behavior, academic achievement, and other outcomes. This study, taken together with results from other studies demonstrating associations between G1 parenting of G2 and G3 outcomes (Capaldi et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2003; Thornberry et al., 2003), suggests that further research into associations between grandparent behaviors and grandchild outcomes is warranted.

Limitations

Several limitations should be kept in mind when considering the implications of the current study. First, the study did not use a genetically informed design, and it is possible that genetic mechanisms may explain, at least in part, intergenerational continuity in problem behavior (D’Onofrio et al., 2007) and even parenting practices. Second, G3 participants spanned a wide age range. Although G3 age was included in tested models, it is possible that developmental differences in the relevance of the examined parenting constructs or the nature of externalizing behavior may not have been captured. Third, measures of parental monitoring were limited. G1 monitoring of G2 was assessed by a single item at each age (13 and 14), and there appeared to be little variation in measures of G2 monitoring of G3. This may explain the lack of association between G2 monitoring and G3 externalizing behavior. Fourth, our hypotheses focus on the effects of parenting practices on child externalizing, but some researchers have argued that child externalizing and parenting practices may be mutually influential (Fite, Colder, Lochman, & Wells, 2006; Stoolmiller, Patterson, & Snyder, 1997). This study cannot establish the direction of causality because measures of parenting practices and child externalizing were collected at the same time. Fifth, this study did not include a measure of G2 adult externalizing or antisocial behavior. It is possible that inclusion of such a measure concurrent with the G2 adult substance use measure would have predicted G3 externalizing behavior, either in addition to or instead of the included G2 adult substance use measure. Further, a measure of G2 adult externalizing behavior may have mediated the relationship between G2 adolescent externalizing and G3 externalizing. Sixth, although we found no evidence for intervention group differences in the intergenerational processes examined, sample size was reduced for these analyses, possibly compromising power to detect small differences between the control and full treatment groups. It is possible that some intervention group differences were missed. Finally, the G2 parents in this study were young when they had their G3 child (oldest age at birth of child = ~22). Results from this study may not generalize to G2 families where the G3s were born to older parents.

Conclusions and Implications

Results from this study and prior work on the intergenerational transmission of parenting suggest that parenting practices are transmitted across generations. Given the small magnitude of the observed continuity in this and other studies, however, it is clear that there is also intergenerational discontinuity in parenting. Thus, results from work so far in this area point to the need for greater understanding of mechanisms of discontinuity. Additional research may help to identify intervention targets useful in decreasing transmission of undesirable parenting practices. This and other prior studies (e.g., Conger et al., 2003; Smith & Farrington, 2004; Thornberry et al., 2003) suggest that, although parenting is related to child antisocial behavior, intergenerational continuity in parenting practices does not account for continuity in child externalizing behavior. Thus, other mechanisms should be explored. In the present study, it was parent substance use and not harsh parenting or parental monitoring that explained the association between G2 and G3 externalizing behavior. This finding highlights the importance of parental drug use as an intervention target in seeking to break intergenerational cycles in child problem behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants # 1RO1DA12138-05 and #R01DA09679-11 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Points of view are those of the authors and are not the official positions of the funding agency.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of our study participants and the SDRG Survey Research Division, as well as Tanya Williams for her help in editing this manuscript.

Appendix A

Unstandardized parameter estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for the Monitoring Model depicted in Figure 3a.

| Parameter | Unstandardized Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Monitoring → G2 Externalizing | −.22 | .06 | −.34 – −.11 |

| G1 Monitoring → G2 Monitoring | .09 | .04 | .01 – .16 |

| G2 Monitoring → G3 Externalizing | −.29 | .37 | −1.0 – .43 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Externalizing | .17 | .07 | .03 – .30 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Age | .65 | .19 | .28 – 1.0 |

| G3 Age → G2 Monitoring | .03 | .02 | −.01 – .06 |

| G3 Age → G3 Externalizing | −.03 | .04 | −.10 – .05 |

Unstandardized parameter estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for the Harsh Parenting Model depicted in Figure 3b.

| Parameter | Unstandardized Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 Harsh Disc → G2 Externalizing | .23 | .06 | .12 – .34 |

| G1 Harsh Disc → G2 Harsh Disc | .23 | .07 | .10 – .36 |

| G2 Harsh Disc → G3 Externalizing | .26 | .11 | .05 – .47 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Externalizing | .17 | .07 | .04 – .30 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Age | .69 | .19 | .32 – 1.1 |

| G3 Age → G2 Harsh Disc | .01 | .02 | −.02 – .05 |

| G3 Age → G3 Externalizing | −.02 | .04 | −.10 – .05 |

Unstandardized parameter estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for the Final Model depicted in Figure 4.

| Parameter | Unstandardized Estimate | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model | |||

| G1 SU → Binge Alc. | .44 | .06 | .31 – .56 |

| G1 SU → Cigarette | .65 | .06 | .53 – .78 |

| G1 SU → Marijuana | .72 | .08 | .57 – .87 |

| G2 SU → Binge Alc. | .49 | .06 | .38 – .60 |

| G2 SU → Cigarette | .73 | .06 | .61 – .85 |

| G2 SU → Marijuana | .61 | .06 | .50 – .73 |

| Structural Paths | |||

| G1 SU → G2 Externalizing | .14 | .06 | .02 – .27 |

| G1 Harsh Disc → G2 Externalizing | .17 | .06 | .07 – .28 |

| G1 IPA → G2 Externalizing | .23 | .07 | .10 – .36 |

| G1 Socio. Risk → G2 Externalizing | .11 | .03 | .05 – .18 |

| G1 Socio. Risk → G2 IPA | .07 | .02 | .02 – .11 |

| G1 SU → G2 SU | .10 | .09 | −.08 – .26 |

| G1 Harsh Disc → G2 Harsh Disc | .24 | .07 | .11 – .38 |

| G1 IPA → G2 IPA | .07 | .04 | −.02 – .15 |

| G1 Socio. Risk → G2 Socio. Risk | .15 | .03 | .09 – .21 |

| G2 Externalizing → G2 SU | .23 | .07 | .09 – .36 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Age | .76 | .20 | .38 – 1.1 |

| G2 Externalizing → G2 Socio. Risk | .24 | .04 | .17 – .32 |

| G2 Externalizing → G3 Externalizing | .12 | .07 | −.02 – .27 |

| G2 SU → G3 Externalizing | .26 | .12 | .03 – .48 |

| G2 Harsh Disc → G3 Externalizing | .27 | .11 | .06 – .49 |

| G2 IPA → G3 Externalizing | −.18 | .19 | −.55 – .18 |

| G2 Socio. Risk → G3 Externalizing | .06 | .11 | −.15 – .27 |

| G3 Age → G3 Externalizing | −.03 | .03 | −.08 – .02 |

| G3 Age → G2 Harsh Disc | .02 | .02 | −.02 – .05 |

| Correlation Specifications | |||

| G1 SU with G1 Harsh Disc | .03 | .03 | −.03 – .10 |

| G1 SU with G1 IPA | .23 | .05 | .15 – .32 |

| G1 SU with G1 Socio. Risk | .37 | .07 | .24 – .50 |

| G1 Harsh Disc with G1 IPA | .06 | .02 | .03 – .09 |

| G1 Harsh Disc with G1 Socio. Risk | .08 | .03 | .03 – .14 |

| G1 IPA with G1 Socio. Risk | .07 | .04 | −.01 – .15 |

| G2 SU with G2 Harsh Disc | .01 | .07 | −.12 – .14 |

| G2 SU with G2 IPA | .09 | .04 | .00 – .17 |

| G2 SU with G2 Socio. Risk | .32 | .06 | .21 – .43 |

| G2 Harsh Disc with G2 IPA | .10 | .02 | .05 – .14 |

| G2 Harsh Disc with G2 Socio. Risk | .10 | .04 | .02 – .18 |

| G2 IPA with G2 Socio. Risk | .06 | .03 | .01 – .11 |

| G2 Socio. Risk with G3 Age | .80 | .19 | .43 – 1.2 |

| G1 Binge Indicator with G2 Binge Indicator | .12 | .06 | .01 – .23 |

| G1 Cig. Indicator with G2 Cig. Indicator | .17 | .05 | .06 – .27 |

| G1 Marij. Indicator with G2 Marij. Indicator | −.03 | .09 | −.20 – .14 |

Footnotes

We tested the parental monitoring and harsh parenting models presented in Figure 3 using only TIP participants and again using the full sample. Because patterns of significance were the same and parameter estimates were nearly identical in the full sample (n = 808) and TIP only (n = 258) analyses and because the full sample provides greater power, we present findings based on the full sample of 808 participants.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/dev.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Akers RL. Deviant behavior: A social learning approach. 2. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Anthony C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Gerard JM, Pemberton S. Interparental conflict and youth problem behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1997;6:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Kerr DCR, Owen LD. Intergenerational and partner influences on fathers’negative discipline. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Patterson GR, Owen LD. Continuity of parenting practices across generations in an at-risk sample: A prosepective comparison of direct and mediated associations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:127–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1022518123387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M, Clark S, Owen LD. Heterosexual risk behaviors in at-risk young men from early adolescence to young adulthood: Prevalence, prediction, and association with STD contraction. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:394–406. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: Predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:106–119. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella L. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Harden KP, Heath AC, et al. Intergenerational transmission of childhood conduct problems: A children of twins study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:820–829. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Wasserman GA, Verdelli L, Greenwald S, Miller LS, Davies M. Maternal Antisocial Behavior, Parenting Practices, and Behavior Problems in Boys at Risk for Antisocial Behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl 1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, Lochman JE, Wells KC. The mutual influence of parenting and boys’ externalizing behavior problems. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Christian RE, Wootton JM. Age trends in the association between parenting practices and conduct problems. Behavior Modification. 1999;23:106–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods for handling missing data. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:226–234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance-abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescencd: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;111:127–155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Davis B, Leve C, Sheeber L. Cross-generational transmission of aggressive parent behavior: A prospective, mediational examination. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:161–169. doi: 10.1023/a:1022522224295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Leff M. Children of substance abusers: Overview of research findings. Pediatrics. 1999:1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Parents’ monitoring -relevant knowledge and adolescents’ delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development. 2003;74:752–768. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Top 10 greatest “hits”: Important findings and future directions for intimate partner violence research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:108–118. doi: 10.1177/0886260504268602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA, Friedrich WN, Fisher J. Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children’s symptomatology: Expert ratings and confirmatory factor analyses of the CBCL. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:683–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, Pears KC. Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, et al. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Kaiser K. Childhood emotional and behavioral problems and educational attainment. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:636–658. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Winn DM, Coie J, Maumary-Gremaud A, Hyman C, Terry R, et al. Motherhood during the teen years: A developmental perspective on risk factors for childbearing. Development and Psychpathology. 1999;11:85 – 100. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JL, Clarke-Stewart KA. Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:771–786. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Mare RD. Recent trends in the inheritance of poverty and family structure. Social Science Research. 2006;35:471–499. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix RL, Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, McFayden-Ketchum SA. The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Development. 1999;70:896–909. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell J, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD. Predicting serious delinquency and substance use among aggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:529–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Substance use risk across three generations: The roles of parent discipline practices and inhibitory control. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:373–386. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children’s negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Barnow S, Preuss UW, Luczak S, Radziminski S. Correlates of externalizing symptoms in children from families of alcoholics and controls. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2003;38:559–567. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Wu CI. Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Farrington DP. Continuities in antisocial behavior and parenting across three generations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:230–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows (Version 16.0.2) Chicago: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Dumenci L, Kamon J, Burstein M. Parenting and children’s externalizing problems in substance-abusing families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:590–600. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M, Patterson GR, Snyder J. Parental discipline and child antisocial behavior: A contingency-based theory and some methodological refinements. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland EH, Cressey DR. Criminology. New York: Lippincott; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA. Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022574208366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]