Abstract

Clinical studies are emerging which suggest that sex hormones may play a role in quit attempts and relapse. The present study aim is to determine if menstrual phase plays a role on a second self-selected quit attempt and subsequent relapse during a twenty-six week follow-up. Participants (n=138) were 29.7 ± 6.5 years old and smoked 16.1 ± 4.8 cigarettes per day. Participants were more likely to self-select a second quit date during the Follicular (F) phase (59.4%) than Luteal (L) phase (40.6%, p = 0.033) and were also more likely to relapse during the F phase than the L phase (59.7% vs. 40.3%, p=0.043, respectively). Those who self-selected to quit in the L phase experienced a significantly longer time to relapse than those who chose the F phase (median of 3 days vs. 2 days, respectively; Hazard Ratio = 1.599, p-value=0.014). This confirms previous work suggesting quit dates in the F phase are associated with worse smoking cessation outcomes. Additional research is needed to investigate how this relationship may vary with the use of pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Females, Menstrual Cycle, Relapse, Quit Date

1. Introduction

Quit attempts in smoking women have been extensively studied given that women are particularly vulnerable to relapse, as well as have multiple health risks of smoking, i.e. lung cancer, osteoporosis, cervical cancer, increase problems with pregnancy including miscarriage, low birth weight and preterm deliveries (United States Department of Health & Human Services, 2001). Studies have shown that female smokers have poorer outcomes in sustaining a quit attempt (Perkins, 2001; Ward et al, 1997; Bjornson et al, 1995; Grunberg et al, 1991) and relapse quicker (Swan et al, 1996; Ward et al, 1997) as compared to men. Some specific barriers to smoking cessation among women have been identified including low confidence (Audrain et al, 1997; Sorensen et al, 1992), negative affect (Borland, 1990; Borrelli et al, 1996), fear of weight gain (Meyers et al, 1997; Pomerleau & Kurth, 1996; Perkins et al, 1997) and depression history (Glassman et al, 2001; Borrelli et al, 1996).

The role of sex hormones (i.e. menstrual cycle) in smoking cessation is still evolving. While the animal literature provides strong evidence for the role of sex hormones in addictive behaviors, the clinical literature is mixed. In animal studies, estrogen has been found to be associated with an increase in self-administration of addictive drugs (Lynch et al 2001; Roth et al, 2002; Roth et al 2004), whereas progesterone decreases self-administration (Mello et al, 2007; Morissette & DiPaolo, 1993; Anker et al 2007) Recent clinical studies have emerged with mixed evidence that sex hormones may play a role in quit attempts and relapse. Some studies have identified the follicular phase (high estrogen, low progesterone) to be associated with poorer smoking cessation outcomes (Allen et al, 2008), whereas others have found that the luteal phase (low estrogen, high progesterone) is associated with poor outcomes (Franklin et al, 2004; Franklin et al, 2008; Carpenter et al, 2008). Clearly, further studies are needed.

In our recent publication on menstrual phase effects on relapse (Allen et al, 2008), we observed that women randomized to quit smoking in the follicular (F) phase had shorter days to relapse than women randomized to quit in the luteal (L) phase. We followed these women who relapsed to determine their subsequent self- selected quit dates and relapse. The primary aim of the present study was to assess the effect of menstrual phase on the self-selected second quit date and on relapse. We hypothesized that women who self-selected a second quit date in the F phase would have fewer days to relapse as compared to women who self-selected a quit date in the L phase. The overall goal of defining these patterns was to gain more understanding of the potential role of sex hormones in quit attempts and relapse in smoking women and to use this knowledge to provide more successful smoking cessation strategies for women.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Female participants were recruited through local media advertisements. Women were screened first by phone, then at a clinic visit. After informed consent was obtained, study eligibility was confirmed from an assessment of the participant’s medical, menstrual and smoking history, blood levels of estrogen and progesterone, and breath carbon monoxide (CO) and saliva cotinine levels to verify smoking status. Participants had to be healthy, between the ages of 18 to 40 year-old, motivated to quit smoking (as indicated by a 7 or higher on a 10-point Likert-type scale), smoke 10 or more cigarettes per day for at least one year, have regular menstrual cycles and not be using exogenous hormones or psychotropic medications (see Allen et al, 2008 for more detail on inclusion/exclusion criteria). As part of the screening visit, women also completed the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al, 1991) and provided demographic information. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Study Protocol

Participants were randomized to quit smoking in either the F phase (days 4–6) or L phase (6–8 days after luteinizing hormone [LH] surge) of their menstrual cycle, with day 1 defined as the first day of menses. Within two to six weeks after enrollment and randomization, participants attended a baseline clinic visit. This visit was timed to occur approximately one week prior to the participant’s randomized quit date. Participants were instructed to quit smoking at midnight on their randomized quit day. Trained counselors provided brief behavioral counseling focusing on personally relevant coping strategies and provided each participant with a self-help manual (National Institute of Health’s Clearing the Air). Counselors were instructed to avoid discussion of the menstrual cycle during counseling sessions. Beginning on their quit date, participants kept daily menstrual cycle calendars and smoking diaries. Participants were followed for 26 weeks with eight clinic visits and two phone calls. Clinic visits occurred in weeks 1 (days 2 and 5), 2 (days 9 and 12), 4, 8, 12, and 26. At each visit, cessation counseling was provided, calendars and diaries were reviewed, blood samples were taken for hormone testing, and smoking status was confirmed via breath CO and saliva cotinine testing. Participants who had relapsed were encouraged, but not required, to set another quit date any time within the next month. Those who relapsed continued in the protocol as described above the same as abstainers. Those participants who relapsed and self-selected a second quit date were the focus of this current data analysis.

2.3 Menstrual Cycle Monitoring

Three methods were used to monitor phase during the study: daily menstrual calendars, urine LH testing (First Response Ovulation Test kit), and monitoring of serum hormone levels (for more details see Allen et al, 2008). For the purposes of this analysis, the L phase was defined as the fourteen days prior to the onset of menses and the F phase was defined as all other days of the menstrual cycle, including menses.

2.4 Self-Selected Second Quit Dates & Relapse

Self-selected second quit date was defined as any 24-hour period of smoking abstinence immediately following a day of smoking anytime after the participants’ randomly assigned quit date. Relapse occurring after the self-selected quit date was defined as a single puff of a cigarette (Hughes et al, 2003). Participants’ smoking status (relapsed or abstinent) was determined retrospectively using daily smoking diaries, Time Line FollowBack (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1991; Sobell & Sobell, 1996) and verified at each clinic visit with a Carbon Monoxide breath analyzer (CO < 5ppm indicating abstinence) and saliva cotinine (<15 ng/ml indicating abstinence).

2.5 Analyses

Among participants who had a self-selected second quit date, we calculated the number and percentage that quit during each menstrual phase. We also calculated the number and percentage that relapsed during each menstrual phase. A Fisher’s exact test and logistic regression were used to investigate the relationship between the second quit date and menstrual cycle phase of second relapse and baseline covariates. Time to second relapse was defined as the number of days between the second quit date and the date of second relapse. We calculated the median time in days to second relapse along with a 95% confidence interval using Kaplan-Meier estimators. Participants who did not have a second relapse were right censored using the date of the last diary entry. A Cox’s regression model was used to investigate the relationship between time to second relapse and baseline covariates. The following covariates were considered for inclusion in the models: initial randomization group, time of first relapse, number of previous quit attempts, length of longest previous quit attempt in days, baseline FTND score, years of smoking, age of smoking initiation, race, and current age. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Backward elimination was used to remove covariates from the model that had p-values ≥ 0.10. Analyses were completed using SAS version 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics/Smoking Behavior

A total of 294 women were enrolled in the original trial. Of those, 31.3% (92/294) withdrew from the study prior to their randomly assigned quit date citing scheduling difficulties, loss of interest in the study, or were lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 202 participants, 138 (68.3%) participants relapsed to smoking after their randomly assigned quit date and subsequently made a second quit attempt. These 138 participants were included in the present analysis. Participants (n=138) were, on average (± standard deviation), 29.7 ± 6.5 years of age, 81.2% white, and 30.7% had a high school education or less. They smoked an average of 16.1 ± 4.8 cigarettes per day and had an average FTND score of 3.9 ± 1.9. Seventy-five (54.4%) of the 138 participants, were initially randomized to quit smoking during the F phase and 63 (45.7%) were randomized to quit during the L phase. Demographics and smoking behaviors of the self-selected second quit date groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics & Smoking Behavior by Self-Selected Quit Phase Group

| All (n=138) | Self-Selected F Phase (n=82) | Self-Selected L Phase (n=56) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 29.7 ± 6.5 | 29.4 ± 6.4 | 30.1 ± 6.8 | 0.537 |

| ≤ 12 years of Education | 42 (30.7%) | 25 (30.5%) | 17 (30.9%) | 1.000† |

| Smoking Behavior | ||||

| CPD | 16.1 ± 4.8 | 16.1 ± 4.7 | 16.0 ± 4.9 | 0.873 |

| Age Started (years) | 16.8 ± 3.8 | 16.5 ± 3.6 | 17.1 ± 4.1 | 0.391 |

| Years of Smoking | 12.9 ± 6.6 | 12.9 ± 6.2 | 13.0 ± 7.2 | 0.894 |

| Number of Previous Quit Attempts | 2.9 ± 2.3 (median = 2) |

2.9 ± 2.3 (median = 2) |

2.9 ± 2.2 (median = 2) |

0.911 |

| Longest Previous Quit (Days) | 185.2 ± 329.8 (median = 30) |

185.9 ± 281.3 (median = 30) |

184.2 ± 394.2 (median = 28) |

0.978 |

| FTND Score | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 0.237 |

Statistics reported as mean ± standard deviation and a two-sided p-value from a t-test unless otherwise noted.

P-value from Fisher’s Exact Test

Among those who were excluded from the data analysis, 31.3% (20/64) were excluded because they remained abstinent after their first quit attempt and 68.8% (44/64) were excluded because they continued daily smoking during the follow-up period.

3.2. Effect of Menstrual Phase on Self-Selected Quit Date and Subsequent Relapse

Significantly more participants self-selected a second quit date in the F phase (59.4%, 82/138) than during the L phase (40.6%, 56/138; exact 2-sided binomial test for equal proportions, p-value = 0.033). The majority of participants (86.2%; 119/138) relapsed after their second quit attempt. Of those who relapsed, most relapsed during the same phase in which they made a quit attempt (65.9%; 91/138). However, overall participants were significantly more likely to relapse during the F phase than the L phase, (71 vs. 48, respectively, exact 2-sided binomial test for equal proportions, p-value = 0.043) regardless of the phase they self-selected for a second quit date (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phase of Self-Selected Quit Date by Phase of Relapse (n=138)

| Phase of Self-Selected Quit Date | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase of Relapse | Follicular (n=82) | Luteal (n=56) | Total (n=138) |

| Follicular | 57 (70%) | 14 (25%) | 71 (51%) |

| Luteal | 14 (17%) | 34 (61%) | 48 (35%) |

| Never Relapsed | 11 (13%) | 8 (14%) | 19 (14%) |

Fisher’s Exact Test, p-value < 0.001, OR = 9.9, 95% Confidence Limits = 4.2–23.2

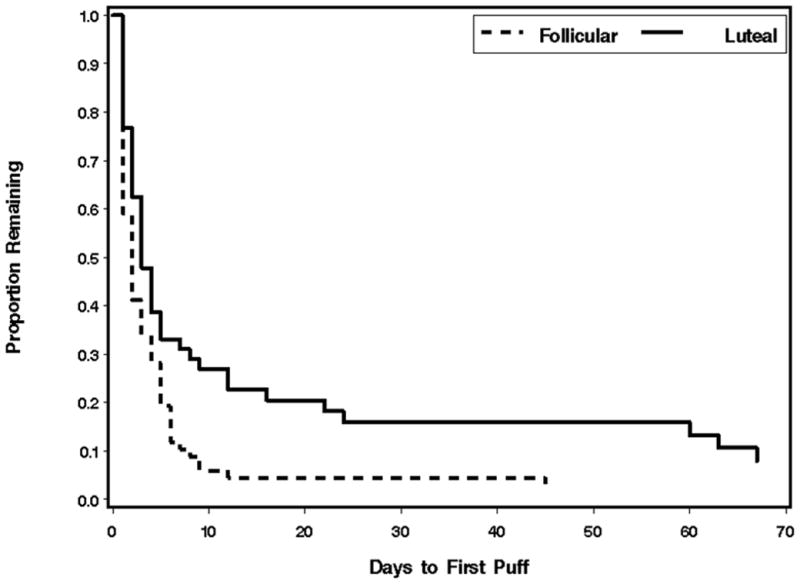

Those who self-selected a second quit date in the L phase experienced a significantly longer time to relapse than those who chose the F phase (Hazard Ratio = 1.599, p-value=0.014). The median time to relapse for those who self-selected the F phase and L phase for a second quit date was 2 days (95% Confidence Interval = 1–3) and 3 days (95% Confidence Interval = 2–5), respectively (Figure 1). Cox’s regression analysis resulted in two significant baseline covariates: age (Hazard Ratio= 0.970, p-value=0.031) and time (days) to first relapse (Hazard Ratio=0.989, p-value=0.058). Adjusting the model for these two covariates yielded similar results (Hazard Ratio = 1.657, p-value=0.0092) to the unadjusted model.

Figure 1.

Time to event curves using ‘one puff’ (continuous abstinence)

Menstrual phase of second relapse was significantly associated with phase of self-selected second quit date (Odds Ratio = 9.9; p-value < 0.0001; Table 2). Adjusting for time from second self-selected quit date to second relapse did not alter the results. Time to second relapse did not significantly predict the menstrual phase of second relapse (p-value = 0.740).

4. Discussion

The results indicate that self-selected quit dates in the follicular phase are associated with a shorter time to relapse as compared to self-selected quit dates in the luteal phase. Our results also indicate that women are more likely to self-select a quit attempt during the follicular phase compared to the luteal phase. Further, the majority of women relapsed within the phase of their self-selected quit attempt but overall women were more likely to relapse to smoking during the follicular phase compared to the luteal phase. In sum, the follicular phase appears to be associated with poorer smoking cessation outcomes in this study sample.

The influence of repeat quit patterns versus effect of ovarian hormones on self-selected second quit date and subsequent relapse is difficult to differentiate. However, it is of note that phase of relapse of second self-selected quit is consistent with our previous publication (Allen et al, 2008) on phase of relapse for randomized first quit. That is, relapse was greatest during the follicular phase compared to the luteal phase whether women were randomized to a quit phase or self-selected a quit phase. In our previous publication we discussed that the higher risk for relapse observed in the follicular phase was possibly related to ovarian hormone influence (Allen et al, 2008). For example, estrogen may enhance subjective mood response to nicotine, the effect of progesterone may attenuate the physiological and subjective effects of nicotine (Sofuoglu et al, 2001), there may be possible alteration of ovarian hormones on nicotine metabolism (Benowitz et al, 2006), or there may be a combination of these factors in play. Although the clinical significance of these observed cycle phase differences remains unknown, the results do suggest that ovarian hormones may play a role.

Our results are in contrast to recent studies of smoking cessation and menstrual phase that have used pharmacotherapy. Franklin et al (2008) conducted a retrospective analysis of women on nicotine replacement and found that relapse occurred more frequently when they quit in the luteal phase as compared to the follicular phase. Similarly, Carpenter et al (2008) conducted a small prospective study of women on nicotine replacement. When measuring point prevalence abstinence two weeks after quit date, they observed that abstinence rates were higher in the follicular group compared to the luteal group. It is possible that the nicotine patch has a moderating influence on the menstrual phase effects. For instance, amelioration of withdrawal symptoms may result in less slips and therefore less reinforcement of smoking during the estrogen dominant follicular phase, whereas in the luteal phase the premenstrual symptoms albeit ameliorated by the nicotine patch (Allen et al, 2000) still may result in more slips resulting in relapse. Or perhaps increased estrogen leads to a more positive response to NRT. Future studies are needed to address the mechanism of these effects.

Our study showed that 75.8% of study participants who relapsed from their initial quit attempt made a second quit attempt approximately four days after their first relapse, on average. Prior studies show despite the fact that 65 to 95% of quit attempts end in failure (Pierce & Gilpin, 2003; Yudkin et al, 2003), large numbers of smokers are interested in quitting again. One study showed that 65% want to make a repeat quit attempt within 30 days consistent across sociodemographic subgroups (Fu et al, 2006). Another study (Joseph et al, 2004) found in a survey of relapsed smokers, that 98% expressed interest in quitting and 50% were ready to quit immediately. Despite this high interest in quitting, it is notable that 86.2% of study participants relapsed to smoking after their second quit attempt. Research indicates that lapse to smoking is a significant predictor of eventual relapse (Kenford et al, 1994). Relapse after second quit attempt was, on average, no greater than three days. Studies (Hughes et al, 2004) show that most relapse occurs early and the majority of smokers relapse within eight days.

The strengths of this study include its prospective nature and building on the initial quit attempt results (Allen, et al 2008) by evaluating the second self-selected quit attempts and relapse with regard to the menstrual cycle. This study also has some limitations. First, smoking status, although confirmed biochemically at clinic visits, was based on self-report and may be misreported on days study participants did not attend clinic visits. Second, we had a relatively large number of women who prematurely withdrawal from the study. Those who prematurely withdrew from the study showed signs of greater nicotine dependence. It is unknown how the level of nicotine dependence may influence the impact of menstrual phase on smoking outcomes. Furthermore, it is difficult to differentiate between phase effect and the function of time in the quit-relapse process. Thus our ability to make inferences regarding the causality of the menstrual cycle on our observed quit-relapse patterns is limited. More research is needed to define the quit-relapse patterns, and the influence of ovarian hormones,

In conclusion, our results suggest that the patterns of second self-selected quit attempts and relapse may be influenced by the menstrual cycle. This confirms our earlier work indicating women who quit in the follicular phase had less favorable outcomes. More research is needed to investigate how this relationship may be altered during smoking cessation attempts assisted by pharmacotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIDA grant 2-R01-DA08075. We thank our research staff – Tracy Bade, Nicole Cordes and Roshan Paudal – for their help with study management, subject recruitment, data measurement and data entry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen SS, Bade T, Center B, Finstad D, Hatsukami DK. Menstrual phase effects on smoking relapse. Addiction. 2008;103:809–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SS, Hatsukami DK, Christianson D, Brown S. Effects of transdermal nicotine on craving, withdrawal and premenstrual symptomatology in short-term smoking abstinence during different phases of the menstrual cycle. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2:231–241. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Larson EB, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Effects of progesterone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in female rates. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;6:472–480. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain J, Gomez-Caminero A, Robertson AR, Boyd R, Orleans CT, Lerman C. Gender and ethnic differences in readiness to change smoking behavior. Journal of Women’s Health. 1997;3:139–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, Jacob P. Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clinical Pharmacolology & Therapeutics. 2006;79:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson W, Rand C, Connett JE, Lindgren P, Nides M, Pope F, Buist AS, Hoppe-Ryan C, O’Hara P. Gender differences in smoking cessation after 3 years in the Lung Health Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:223–230. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R. Slip-ups and relapse in attempts to quit smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli B, Bock B, King T, Pinto B, Marcus BH. The impact of depression on smoking cessation in women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12:378–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, Leinbach AS, Larowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Menstrual phase effects on smoking cessation: A pilot feasibility study. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:293–301. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Ehrman R, Lynch KG, Harper D, Sciortino N, O’Brien CP, Childress AR. Menstrual cycle phase at quit date predicts smoking status in an NRT treatment trail: A retrospective analysis. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:287–292. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Napier K, Ehrman R, Gariti P, O’Brien CP, Childress AR. Retrospective study: Influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:171–175. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu SS, Partin MR, Snyder A, An LC, Nelson DB, Clothier B, Nugent S, Willenbring ML, Joseph AM. Promoting repeat tobacco dependence treatment: are relapsed smokers interested? American Journal of Managed Care. 2006;12:235–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Covey LS, Stetner F, Rivelli S. Smoking cessation & the course of major depression: A follow-up study. Lancet. 2001;357:1929–1932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg NE, Winders SE, Wewers ME. Gender differences in tobacco use. Health Psycholology. 1991;10:143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the fagerstrom to tolerance questionnaire. British Journal Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GR. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tobacco & Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Rice K, An LC, Mohiuddin A, Lando H. Recent quitters’ interest in recycling and harm reduction. Nicotine Tobacco & Research. 2004;6:1075–1077. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331324893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation. Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA. 1994;271:589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Mickelberg JL, Carroll ME. Role of estrogen in the acquisition of intravenously self-administered cocaine in female rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2001;68:641–646. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Knudson IM, Mendelson JH. Sex and menstrual cycle effects on progressive ratio measures of cocaine self-administration in cynomolgus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1956–1966. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers AW, Klesges RC, Winders SE, Ward KD, Peterson BA, Eck LH. Are weight concerns predictive of smoking cessation? A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:448–452. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette M, DiPaolo T. Effect of chronic estradiol and progesterone treatments of ovariectomized rats on brain dopamine uptake sites. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;60:1876–1883. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Levine MD, Marcus MD, Shiffman S. Addressing women’s concerns about weight gain due to smoking cessation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K. Smoking cessation in women: Special consideration. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:391–411. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. A minimum 6-month prolonged abstinence should be required for evaluating smoking cessation trials. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:151–153. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000083427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Kurth CL. Willingness of female smokers to tolderate postcessation weight gain. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1996;8:371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Casimir AG, Carroll ME. Influence of estrogen in the acquisition of intravenously self-administered heroin in female rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2002;72:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth ME, Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Sex differences in vulnerability to drug abuse: A review of preclinical studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back User’s Guide. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Babb DA, Hatsukami DK. Progresterone treatment during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: effects on smoking behavior in women. Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior. 2001;69:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Goldberg R, Ockene J, Klar J, Tannenbaum T, Lemeshow S. Heavy smoking among a sample of employed women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1992;8:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan GE, Ward MM, Jack LM. Abstinence effects as predictors of 28-day relapse in smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ. Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkin P, Hey K, Roberts S, Welch S, Murphy M, Walton R. Abstinence from smoking eight years after participation in randomized controlled trial of nicotine patch. British Medical Journal. 2003;327:28–29. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7405.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]