Abstract

In many species germ cells form in a specialized germ plasm, which contains localized maternal RNAs [1–5]. In the absence of active transcription in early germ cells, these maternal RNAs encode germ cell components with critical functions in germ cell specification, migration and development [6, 7]. For several RNAs, localization has been correlated with release from translational repression, suggesting an important regulatory function linked to localization [3, 4, 8, 9]. To address the role of RNA localization and translational control more systematically, we assembled a comprehensive set of RNAs that are localized to polar granules, the characteristic germ plasm organelles. We find that the 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of all RNAs tested control RNA localization and instruct distinct temporal patterns of translation of the localized RNAs. We demonstrate necessity for translational timing by swapping the 3′UTR of polar granular component (pgc), which controls translation in germ cells, with that of nanos, which is translated earlier. Translational activation of pgc is concurrent with extension of its poly(A) tail length, but appears largely independent of the Drosophila CPEB homolog ORB. Our results demonstrate a role for 3′UTR mediated translational regulation in fine-tuning the temporal expression of localized RNA and may provide a paradigm for other RNAs that are found enriched at common cellular locations such as the leading edge of fibroblasts or the neuronal synapse.

Results and Discussion

Translation of germ plasm RNAs is temporally regulated by their 3′UTRs

To investigate the translational state of germ line localized RNAs, we assembled a list of RNAs localized to germ plasm using publicly available databases and published reports. We used data from the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) in situ database, the embryo data base by Lecuyer et al. and literature searches to assemble a list of RNAs present in germ cells and then tested these RNAs for their mode of germ cell localization [10, 11]. We based our analysis on the expression patterns of RNAs previously known to be localized to the germ plasm such as nanos, germ cell less (gcl) and polar granule component (pgc); by electron microscopy these RNAs were shown to be localized to the polar granules, which are integral RNA-protein components of germ plasm [12, 13]. nanos, gcl and pgc are initially localized in the form of a crescent at the posterior pole of the embryo (stage 1–2) and are then incorporated into developing germ cells (stage 3–4). Our analysis suggests that about ~33% (58/171) of germ cell RNAs are localized in a manner similar to nanos, gcl and pgc, while the remaining RNAs are protected in germ cells by selective stabilization without prior localization (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The majority of maternally synthesized RNA is not localized or protected and this RNA is degraded at the transition from maternal to zygotic gene expression (stage 4–5) [8, 14–18]. Of the 58 genes with expression patterns comparable to nanos, gcl and pgc we selected 11 for further analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. RNAs localized to germ plasm.

Column 1 lists RNAs localized to germ plasm. Column 2 shows the function of these localized RNAs. Column 3 shows RNAs that were localized to the germ plasm by performing in situ hybridization (data not shown) and databases used to identify RNAs localized to germ plasm. Column 4 shows RNAs that form RNA islands similar to those described for nanos RNA [48]. Islands of germ plasm form when nuclei migrate into the germ plasm at nuclear cycle 9; RNA island formation is a characteristic feature of germ plasm localized RNAs. Column 5 lists 3′UTRs sufficiency to localize reporter construct to the germ plasm (see also Supplementary Figure 1).

| RNA | Function | Germ plasm# | RNA islands# | 3′UTR Sufficiency | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nos | Translational control | + | + | + | [45] |

| bruno | Translational control | + | + | + | This study |

| pgc | Transcriptional silencing | + | + | + | This study |

| gcl | Germ cell formation | + | + | + | This study |

| CG5292 | RNA binding* | + | + | + | This study |

| sra | Ca2+ signaling | + | + | + | This study |

| CG18446 | Zinc ion binding* | + | + | + | This study |

| CG2774 | Endocytosis* | + | + | + | This study |

| cyclin B | Cell Cycle | + | + | + | [46] |

| orb | Translational control | + | + | + | This Study, [20] |

| rapgap1 | GTPase | + | + | ND | [47] |

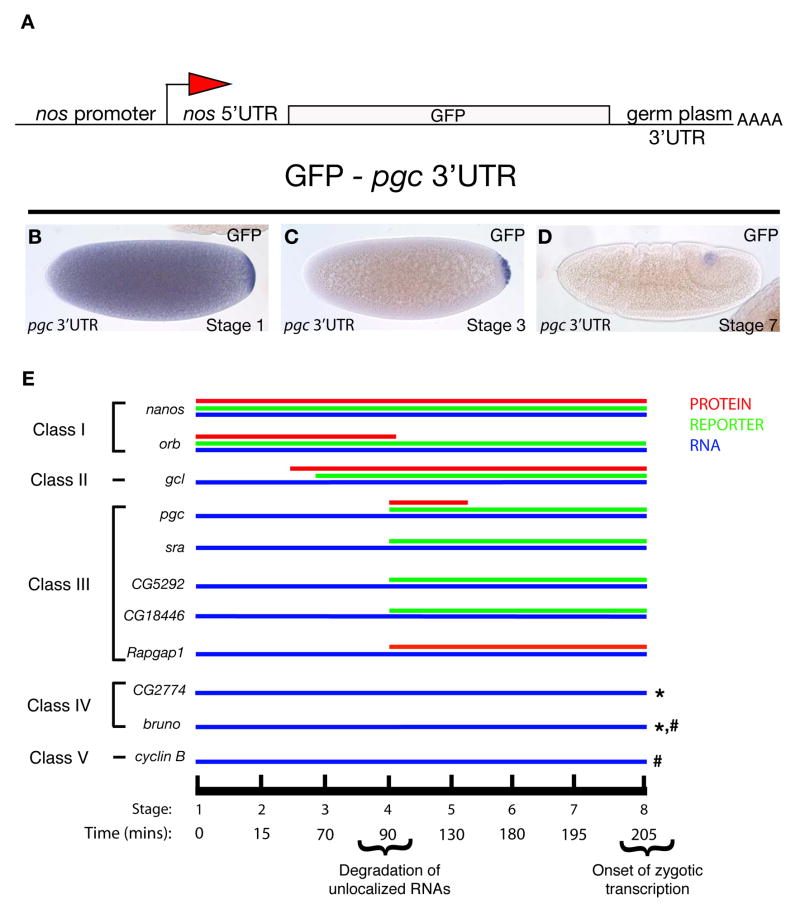

In the case of nanos, RNA translation in the embryo is linked to its localization to the germ plasm, and both aspects of RNA regulation are mediated by the nanos 3′UTR [8]. In order to determine whether this link between RNA localization and translation applies more generally to RNAs localized to the germ plasm and is mediated by 3′UTRs, we generated reporter constructs containing the 3′UTRs of selected localized RNAs and used previously described reporters for nanos and orb [19, 20]. We fused the maternally active nanos promoter and its 5′UTR to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding region, which carried a HA-tag on both the C- and N-termini, and added to this reporter cassette the 3′UTRs of selected localized RNAs (Figure 1A). We assayed the resulting transgenic lines for localization to the germ plasm by using in situ hybridization analysis for GFP RNA. For each of the seven transgenes generated, the 3′UTR was sufficient for germ plasm localization as well as degradation of the uniformly distributed RNA that is found throughout the embryo (Table 1, Figure 1B–D, Supplementary Figure 1B–K). To determine if the localization pattern of these hybrid transgenic constructs was germ plasm dependent, we tested a reporter construct containing the pgc 3′UTR (pnos::HA-GFP-HA pgc 3′UTR) in an oskar (osk) mutant background in which germ plasm is not formed (Supplementary Figure 2). GFP RNA was not localized to the posterior pole in embryos from osk mutant mothers. We confirmed this result by crossing the transgene into females that carried an osk-bcd 3′UTR transgene; in this genetic background germ plasm is formed ectopically at the anterior pole due to OSK mediated assembly of germ plasm at the anterior pole and the expression of the reporter is found at the anterior (Supplementary Figure 2) [21]. Thus in both assays, localization of the hybrid pgc reporter construct was dependent on a functional germ plasm.

Figure 1. Translational regulation of germ plasm RNAs.

A. Diagram shows the GFP-HA-3′UTR reporter cassette used in this study. For nanos 3′UTR, GFP was fused to moesin instead of HA [19]. Orb 3′UTR was fused to LacZ [20] B–D. pgc 3′UTR recapitulates endogenous RNA localization. In situ hybridization for GFP RNA at different stages of embryogenesis shows degradation of unlocalized pgc RNA and protection of localized RNAs in germ cells. E. Classification of germ plasm localized RNAs according to onset of translation. Blue line represents endogenous RNA. Green line represents translation of the reporter construct under control of respective 3′UTRs. Red line represents endogenous protein expression when antibodies were available. Stages of embryonic development and corresponding developmental time after egg deposition are indicated by the black line. Lines marked with (*) were tested for reporter expression only and showed no expression of GFP/HA. Lines marked with (#) were tested for expression of endogenous protein and showed no protein expression. Stages as indicated, posterior of the embryo is to the right.

As the reporter constructs demonstrated that 3′UTRs were sufficient to localize RNAs to the germ plasm, we wanted to analyze the translational state of these RNAs beginning at the germ plasm stage (stage 1) through stage 8 of embryogenesis, when zygotic transcription is initiated in germ cells [22]. In addition to following the expression of GFP protein translated by the respective reporter construct, we analyzed the expression of endogenous proteins when antibodies were available. The results are summarized in Figure 1E and Supplementary Figures 3–6. In general, we found that all localized RNAs tested were translationally regulated. With the exception of cyclin B, the reporter RNAs were not translated outside the germ plasm in the early embryo. Although all of the RNAs analyzed showed an apparently identical localization to germ plasm, the onset of translation varied and we observed distinct patterns, which we assigned to five different classes. Class I RNAs such as nanos and orb are already translated in the germ plasm (stage 1) (Supplementary Figure 3). Class II RNAs such as gcl are repressed in germ plasm and translated at nuclear cycle 9 just before germ cell formation (stage 2–3) (Supplementary Figure 4). Class III RNAs including pgc, sra, CG5292, CG18446 and Rapgap1 are translationally repressed in the germ plasm and translationally active concurrent with germ cell formation (stage 4) (Supplementary Figure 5). Class IV RNAs such as bruno and CG2774 are not translated in germ cells during embryogenesis (Supplementary Figure 6). Class V includes cyclin B, which is translationally repressed in germ plasm and germ cells and activated at stage 16, when germ cells have reached the somatic gonad [23, 24]. By utilizing available antibodies or published protein expression patterns we found that the onset of translation was identical between the respective reporter constructs and the endogenous proteins for PGC, GCL, NANOS and BRUNO [25–28]. However, GFP protein often persisted in germ cells beyond detection of the endogenous protein (Supplementary Figure 7), likely due to differences in protein stability. To address whether the amount of RNA localized may affect the timing of translation, we compared the onset of translation in embryos that received two copies of the pnos::HA-GFP-HA pgc 3′UTR transgene from their mother to embryos that had received one copy of the transgene and embryos with reduced germ plasm (derived from mothers heterozygous for oskar). While the amount of RNA localized to the germ plasm clearly differed, the onset of translation was not affected (Supplementary Figure 8). Taken together, our analysis of an extended number of localized RNAs suggests that RNA localization per se does not trigger translation and demonstrates that discrete information encoded by specific 3′UTRs dictates the exact timing of expression of a localized RNA.

Translation of pgc is associated with polyadenylation

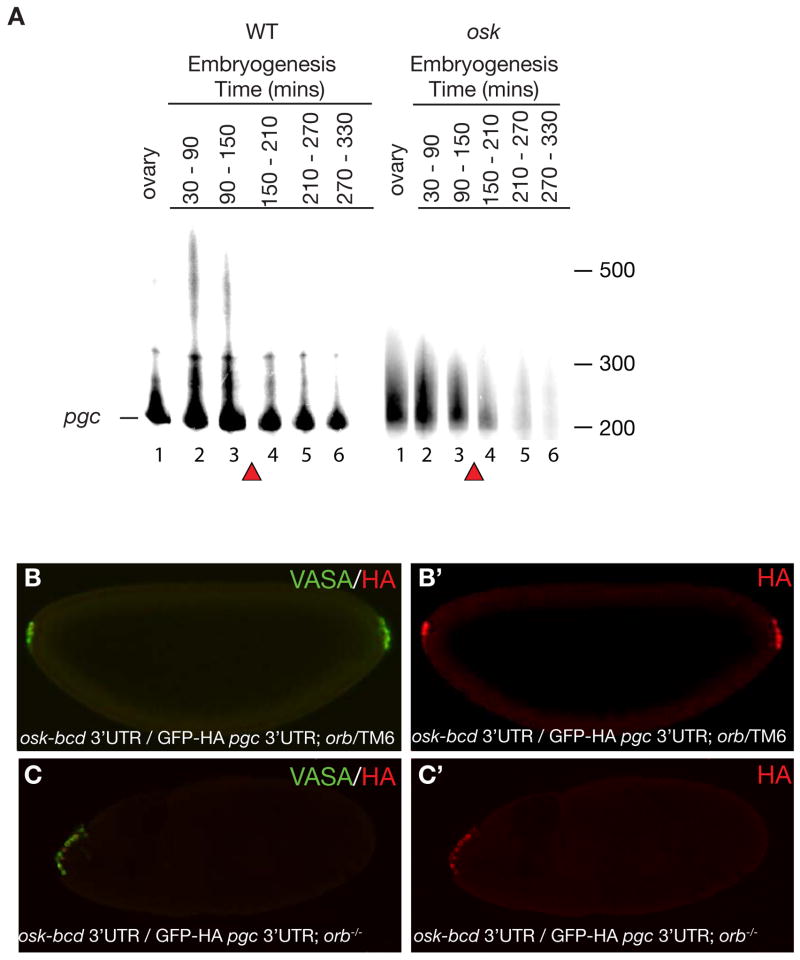

To further explore the link between 3′UTR-mediated localization and subsequent activity, we chose to focus on Class III RNAs, namely pgc and four other RNAs, for which translation was repressed during the early cleavage stages of embryogenesis and was activated upon germ cell formation (Figure 1E, Supplementary Figure 5). This particular pattern suggests that these protein products may perform functions required specifically in newly formed germ cells. Indeed, pgc, the best-studied representative of this class of RNAs, controls transcriptional silencing in germ cells at this stage [25, 29]. To determine how translation is induced upon germ cell formation, we determined if pgc activation is mediated by poly(A) tail elongation, a common mechanism of 3′UTR regulation [30]. We collected cDNA from adult ovaries and timed embryo collections using progeny from wild-type and oskar (osk) mutant flies and performed poly(A) tail length (PAT) assays [31]. Using RT-PCR we could detect an amplicon for pgc RNA during oogenesis in both wild-type and osk mutant flies (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 9A, B). During embryogenesis, we detected a strong pgc RNA signal between stages 1–4 (0–150 mins after egg deposition (AED)) and a weaker signal until stage 8 (330 mins AED) in wild-type embryos; this result is consistent with the degradation of the majority of unlocalized pgc RNAs during the maternal to zygotic transition of gene expression at stage 4–5 and protection of the localized RNA in germ cells [14]. Indeed, in osk mutants in which pgc RNA is not localized to germ cells, we detected pgc until stage 3–4 but not at later stages (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 9B). Using the PAT assay, we detected a prominent RNA species with a short poly(A) tail of about 100 nucleotides (nt) during oogenesis and embryogenesis in wild-type and osk mutant embryos; an additional, longer poly(A) tail of about 200–250 nt was present in the 0.5–1.5 hour collection from wild-type embryos (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 9B). Only 12% percent of the total RNA was shifted to the longer tail length (Supplementary Figure 9C). These data are consistent with previous studies showing that only a small fraction (4–18%) of total nanos and oskar RNA, respectively, are localized [32]. Since the long poly(A) tail species of pgc RNA were only detected in wild-type embryos, but not in osk mutant embryos, we conclude that the long poly(A) tail is only present when pgc RNA is localized to the germ plasm and translated in germ cells. We also analyzed the length of the poly(A) tail of Class IV RNA bruno, which is localized but not translated during germ cell formation. During oogenesis when bruno is translated it has a long poly(A) tail of 350–400 nt (Supplementary Figure 9D) [28]. However, during embryogenesis bruno is not translated and has a short poly(A) tail of about 75 nt. A short poly(A) tail is also observed in oskar mutants (Supplementary Figure 9D). Taken together our data show that translation of localized RNA correlates with an increase in poly(A) tail length and suggest that polyadenylation is one of the mechanisms that triggers 3′UTR-mediated translational timing.

Figure 2. Translation of pgc is concurrent with poly(A) tail extension and is CPEB independent.

A. PAT assay was performed for pgc RNA as indicated in materials and methods and products were run on an urea denaturing acrylamide gel. Poly(A) tail length of ovaries and embryos from wild-type and osk mutant females. Lane 1: Ovary; Lane 2: 30–90 mins AEL (stage 1–3); Lane 3: 90–150 mins AEL (stage 3–4); Lane 4: 150–210 mins AEL (stage 4–5); Lane 5: 210–270 mins AEL (stage 5-6-7); Lane 6: 270–330 mins AEL (stage 8–10). The baseline band indicated by a line corresponds to the shortest amplified fragment at 200nt. Poly(A) tail length is measured form this line. Red triangles mark the maternal to zygotic transition during which unlocalized maternal RNAs are degraded. A loading control for wild-type and osk mutant embryos is shown in Supplementary Figure 9. B and B′. Germ cells are formed at both anterior as well as posterior poles of embryos from osk-bcd 3′UTR/ pnos::HA-GFP-HA-pgc 3′UTR; orbmel/TM6 mothers. (B) Merge of both VASA and HA antibody, (B′) stained for GFP-HA reporter. C and C′. Germ cell formation only at anterior pole and not posterior pole in embryos from osk-bcd 3′UTR/ pnos::HA-GFP-HA-pgc 3′UTR; orbmel /orb343 mothers. (C) Merge of both VASA and HA antibody, (C′) stained for GFP-HA reporter. Posterior of the embryo is to the right.

One mechanism by which pgc RNA poly(A) tail length may be regulated is by regulated access of the Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element binding protein (CPEB) to the RNA. In neuronal granules, as well as during oocyte maturation of Xenopus laevis eggs, repressed RNAs are activated by poly(A) elongation via the activity of CPEBs [33]. Drosophila has two CPEBs; of these the one encoded by the orb gene is predominantly expressed in the germ line. orb RNA and protein are both present in germ plasm and in germ cells (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 10). However, genetic analysis of ORB’s role in germ plasm translation is difficult. ORB plays essential roles during oogenesis including positively regulating the translation of osk at the posterior pole of the oocyte [34, 35]. Indeed, the weak orbmel allele has a phenotype similar to that of osk, and embryos laid by orbmel mothers fail to assemble germ plasm or form germ cells, precluding the direct analysis of a later role of ORB in germ plasm or germ cells [36].

To assess if ORB is required for pgc RNA poly(A) tail elongation and translational activation we circumvented the necessity for orb in the translation of osk and thus the formation of germ plasm. We localized osk RNA to the anterior pole of the embryo by utilizing the bcd 3′UTR [15]. Embryos from orbmel/orb343 mutant mothers, carrying both the osk-bcd 3′UTR and pnos::GFP-HA-pgc 3′UTR transgenes, were collected and stained for VASA, a germ cell marker, and the HA tag to detect expression from the GFP-HA-pgc 3′UTR transgene (Figure 2B–C). The mutant embryos had no germ cells at the posterior end, confirming the role of ORB protein in the synthesis of endogenous OSK protein. VASA positive cells, however, were detected at the anterior pole, which also stained positively for HA (Figure 2B–C). Thus, orb does not affect the translation of pgc and germ cell less (gcl), which are required for germ cell specification and formation downstream of osk [26]. Low levels of ORB activity present in the orbmel mutant could be sufficient for pgc and gcl translation but not for osk translation or the Drosophila poly(A) polymerase, hiiragi (hrg), which has been shown to act cooperatively with ORB for osk translation, acts independently of ORB for pgc and gcl regulation [37]. Alternatively, rather than polyadenylation, deadenylation may be the regulated component that controls the onset of pgc and gcl translation. Indeed, the CCR4-Not-Pop2 deadenylation complex has been shown to control Cyclin B RNA translational repression in early germ cells [24].

Polar granules coordinate translation of germ plasm RNAs

The role of polar granules in the regulation of germ cell RNAs remains elusive. In somatic cells, Processing (P) bodies are known centers of RNA repression [38]. As polar granules share common components with P bodies, it has been proposed that polar granules are centers of RNA repression [6, 39]. However, EM studies have also shown that polar granules contain ribosomes, thereby predicting a more active role in translation [13]. Among the localized germ plasm RNAs that we investigated, nanos, gcl and pgc are found in polar granules by electron microscopy at the germ plasm stage [12, 13]. These three RNAs are translated at different time points, namely at the germ plasm (stage 1), germ bud (stage 2–3) and germ cell stage (stage 4) respectively. If polar granules had a solely repressive or activating role, one might expect that the association of these RNAs with polar granules would change during development as each RNA becomes translated. We used a transgenic line that expressed an Aubergine-GFP fusion protein (AUB-GFP), to mark polar granules [40, 41] while also assessing nos, pgc and gcl RNA localization by fluorescent in situ hybridization. We found that all three RNAs co-localize with polar granules during all stages of germ cell formation (Supplementary Figure 11, 12). While it is possible that small amounts of RNA leave the granules and are then translated, we favor the hypothesis that polar granules are dynamic centers of RNA regulation that control both RNA repression and translation.

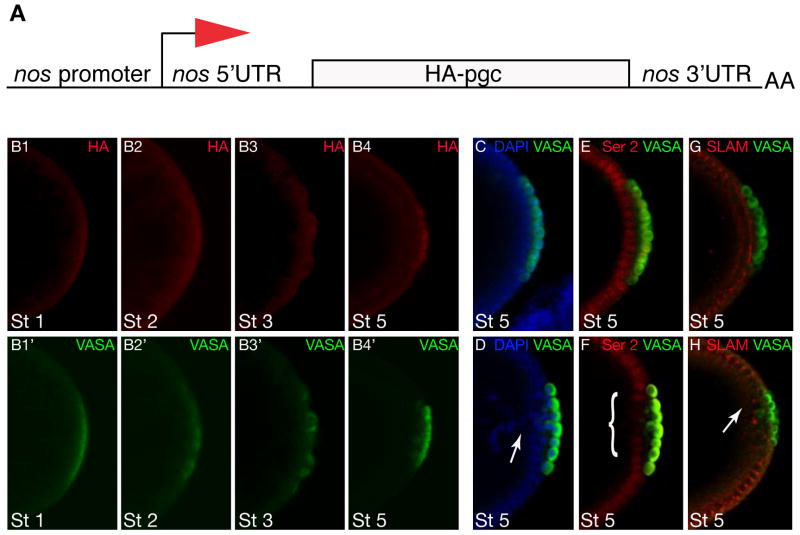

Regulation of translation by 3′UTR is important for proper development

Our results show that germ line RNAs are translationally regulated during embryogenesis in a temporally restricted manner. We next wanted to determine whether altering the temporal expression of these RNAs by switching 3′UTRs had consequences for proper germ line or somatic development. We chose pgc because of its role as a global transcriptional repressor in germ cells, a function that is required when germ cells form [29]. Furthermore, ectopic expression of pgc causes transcriptional silencing in somatic tissues [25]. We swapped the pgc 3′UTR, which restricts translation to the germ cell stage (stage 4), with the nanos 3′UTR, which confers translational activation earlier as oocytes mature during late oogenesis and in germ plasm (Figure 3B1–B4′) [42]. In transgenic lines that carry pgc under the control of the nanos 3′UTR, somatic cells located adjacent to the germ cells failed to cellularize properly and nuclei fell into the yolk, leaving a “pole hole” in ~50% (≥3 cells) of embryos (n = 75) compared to ~10% in wild type (n=70) (Figure 3C–D). Since PGC protein represses transcription in a global manner, we asked whether ectopic PGC protein reduces the expression of zygotically expressed genes that are required for somatic cell formation. We therefore analyzed the status of RNA Polymerase II activity by staining embryos with an antibody that recognizes phosphorylation of Ser2 (P-Ser2) in the Carboxy Terminal Domain (CTD) of RNA Polymerase II, a marker for active transcription. In embryos with precocious PGC translation, the pSer2 epitope was reduced in the nuclei of the posterior blastoderm and consequently these nuclei expressed lower levels of proteins like SLAM that are required for somatic cellularization (Figure 3E–H). We conclude that temporal regulation of germ plasm restricted RNAs like pgc is important to segregate the germ line program from the somatic program.

Figure 3. Precocious expression of PGC affects embryonic development.

A. Diagram showing the pnos::PGC-HA-nos 3′UTR construct used in this experiment to translate pgc in the germ plasm under the control of the nos 3′UTR. B. Nos-like translation pattern of embryos from mothers carrying pnos::PGC-HA-nos 3′UTR reporter construct. B1–B4 immuno-staining for HA shows translation in germ plasm and germ cells. B1′-B4′ immuno-staining for VASA shows staging of germ line development. C and D. Wild-type embryo (C) and embryo from pnos::PGC-HA-nos 3′UTR female (D) stained for nuclei in blue (DAPI) and germ cells in green (VASA). The somatic cells adjacent to the germ cells form a continuous epithelial layer in the wild type (C) but fail to cellularize properly and fall back into the yolk (“Pole hole phenotype”) in the embryo that precociously expresses PGC (arrow). E and F. Wild-type embryo (E) expresses high levels of active RNAPol II (detected by antibodies against the P-Ser2 epitope in the of RNAPol II CTD in red) in somatic cells adjacent to the germ cells (VASA, green); note that germ cells are transcriptionally silent due to PGC function. Embryo from pnos::PGC-HA-nos 3′UTR female (F) expresses reduced levels of the P-Ser2 epitope (red (marked by bracket)) in somatic cells adjacent to germ cells (VASA, green) because of expanded expression of PGC. G and H. Wild-type embryo (H) immunostained for Slow as molasses (SLAM) (red) a zygotically expressed gene required for somatic cellularization; germ cells stained for VASA in green. Expression of SLAM is disrupted in embryo from female carrying the pnos::PGC-HA-nos 3′UTR transgene (H, arrow). Stages as indicated, posterior is to the right.

Conclusion

By systematically analyzing RNAs localized to germ plasm in the embryonic germ line we show that 3′UTRs play an instructive role in the spatial and temporal control of germ line expression, a role made especially critical due to the lack of active transcription in early germ cells. In general, sequences within the 3′UTR restrict and protect RNAs with function in germ line biology to the germ cells. Moreover, the 3′UTR also harbors a specific program to repress and activate translation at distinct times of development. Thus, contrary to previous findings with oskar and nanos RNA, which suggested a mechanism by which translational repression was relieved concomitant with localization, our results suggest that additional mechanisms regulate translation during different stages of germ line development. Our results suggest that association with polar granules may not be limited to translationally active or repressed RNAs. Since transcription is repressed in germ cells, intrinsic timing mechanisms need to control the activity of transacting factors or the accessibility of RNA structure to relieve repression within polar granules. Large scale RNA localization is not unique to Drosophila germ plasm but has also been observed in migrating fibroblasts and in neuronal dendrites [43, 44]. So far only a small number of RNAs have been analyzed in detail for their regulation. A more systematic analysis of regulated RNAs should provide new insight into the logic contained in 3′UTRs that instructs specific translational outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lehmann lab members for critically reading the manuscript. We want to thank Alexey Arkov for the gift of the plasmid containing the nanos promoter with the nanos 5′UTR linked to GFP. We are particularly grateful to Daria Siekhaus and Noelle Paffett-Lugassy for discussion and comments on the manuscript. We thank Paul Schedl and Iswar Hariharan for flies and antibodies. P.R. is a HHMI Research Associate. R.G.M. was an EMBO and a Human Frontiers Science Program postdoctoral fellow. R.L. is a HHMI investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.King ML, Messitt TJ, Mowry KL. Putting RNAs in the right place at the right time: RNA localization in the frog oocyte. Biol Cell. 2005;97:19–33. doi: 10.1042/BC20040067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knaut H, Steinbeisser H, Schwarz H, Nusslein-Volhard C. An evolutionary conserved region in the vasa 3′UTR targets RNA translation to the germ cells in the zebrafish. Curr Biol. 2002;12:454–466. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ephrussi A, Dickinson LK, Lehmann R. Oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell. 1991;66:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90137-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim-Ha J, Smith JL, Macdonald PM. oskar mRNA is localized to the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Cell. 1991;66:23–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90136-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illmensee K, Mahowald AP. Transplantation of posterior polar plasm in Drosophila. Induction of germ cells at the anterior pole of the egg. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:1016–1020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seydoux G, Braun RE. Pathway to totipotency: lessons from germ cells. Cell. 2006;127:891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cinalli RM, Rangan P, Lehmann R. Germ cells are forever. Cell. 2008;132:559–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavis ER, Lehmann R. Translational regulation of nanos by RNA localization. Nature. 1994;369:315–318. doi: 10.1038/369315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunkel N, Yano T, Markussen FH, Olsen LC, Ephrussi A. Localization-dependent translation requires a functional interaction between the 5′ and 3′ ends of oskar mRNA. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1652–1664. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecuyer E, Yoshida H, Parthasarathy N, Alm C, Babak T, Cerovina T, Hughes TR, Tomancak P, Krause HM. Global analysis of mRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell. 2007;131:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomancak P, Berman BP, Beaton A, Weiszmann R, Kwan E, Hartenstein V, Celniker SE, Rubin GM. Global analysis of patterns of gene expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R145. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura A, Amikura R, Mukai M, Kobayashi S, Lasko PF. Requirement for a noncoding RNA in Drosophila polar granules for germ cell establishment. Science. 1996;274:2075–2079. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amikura R, Kashikawa M, Nakamura A, Kobayashi S. Presence of mitochondria-type ribosomes outside mitochondria in germ plasm of Drosophila embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9133–9138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171286998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tadros W, Houston SA, Bashirullah A, Cooperstock RL, Semotok JL, Reed BH, Lipshitz HD. Regulation of maternal transcript destabilization during egg activation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2003;164:989–1001. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bashirullah A, Halsell SR, Cooperstock RL, Kloc M, Karaiskakis A, Fisher WW, Fu W, Hamilton JK, Etkin LD, Lipshitz HD. Joint action of two RNA degradation pathways controls the timing of maternal transcript elimination at the midblastula transition in Drosophila melanogaster. Embo J. 1999;18:2610–2620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tadros W, Goldman AL, Babak T, Menzies F, Vardy L, Orr-Weaver T, Hughes TR, Westwood JT, Smibert CA, Lipshitz HD. SMAUG is a major regulator of maternal mRNA destabilization in Drosophila and its translation is activated by the PAN GU kinase. Dev Cell. 2007;12:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushati N, Stark A, Brennecke J, Cohen SM. Temporal reciprocity of miRNAs and their targets during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding D, Parkhurst SM, Halsell SR, Lipshitz HD. Dynamic Hsp83 RNA localization during Drosophila oogenesis and embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3773–3781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sano H, Renault AD, Lehmann R. Control of lateral migration and germ cell elimination by the Drosophila melanogaster lipid phosphate phosphatases Wunen and Wunen 2. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:675–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantz V, Schedl P. Multiple cis-acting targeting sequences are required for orb mRNA localization during Drosophila oogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2235–2242. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ephrussi A, Lehmann R. Induction of germ cell formation by oskar. Nature. 1992;358:387–392. doi: 10.1038/358387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Doren M, Williamson AL, Lehmann R. Regulation of zygotic gene expression in Drosophila primordial germ cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asaoka-Taguchi M, Yamada M, Nakamura A, Hanyu K, Kobayashi S. Maternal Pumilio acts together with Nanos in germline development in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:431–437. doi: 10.1038/15666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadyrova LY, Habara Y, Lee TH, Wharton RP. Translational control of maternal Cyclin B mRNA by Nanos in the Drosophila germline. Development. 2007;134:1519–1527. doi: 10.1242/dev.002212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanyu-Nakamura K, Sonobe-Nojima H, Tanigawa A, Lasko P, Nakamura A. Drosophila Pgc protein inhibits P-TEFb recruitment to chromatin in primordial germ cells. Nature. 2008;451:730–733. doi: 10.1038/nature06498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jongens TA, Hay B, Jan LY, Jan YN. The germ cell-less gene product: a posteriorly localized component necessary for germ cell development in Drosophila. Cell. 1992;70:569–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90427-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Lehmann R. Nanos is the localized posterior determinant in Drosophila. Cell. 1991;66:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90110-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster PJ, Liang L, Berg CA, Lasko P, Macdonald PM. Translational repressor bruno plays multiple roles in development and is widely conserved. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2510–2521. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinho RG, Kunwar PS, Casanova J, Lehmann R. A noncoding RNA is required for the repression of RNApolII-dependent transcription in primordial germ cells. Curr Biol. 2004;14:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter JD. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation in development and beyond. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:446–456. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.446-456.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salles FJ, Richards WG, Strickland S. Assaying the polyadenylation state of mRNAs. Methods. 1999;17:38–45. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergsten SE, Gavis ER. Role for mRNA localization in translational activation but not spatial restriction of nanos RNA. Development. 1999;126:659–669. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter JD. CPEB: a life in translation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christerson LB, McKearin DM. orb is required for anteroposterior and dorsoventral patterning during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:614–628. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lantz V, Chang JS, Horabin JI, Bopp D, Schedl P. The Drosophila orb RNA-binding protein is required for the formation of the egg chamber and establishment of polarity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:598–613. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castagnetti S, Ephrussi A. Orb and a long poly(A) tail are required for efficient oskar translation at the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2003;130:835–843. doi: 10.1242/dev.00309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juge F, Zaessinger S, Temme C, Wahle E, Simonelig M. Control of poly(A) polymerase level is essential to cytoplasmic polyadenylation and early development in Drosophila. Embo J. 2002;21:6603–6613. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomson T, Liu N, Arkov A, Lehmann R, Lasko P. Isolation of new polar granule components in Drosophila reveals P body and ER associated proteins. Mech Dev. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones JR, Macdonald PM. Oskar controls morphology of polar granules and nuclear bodies in Drosophila. Development. 2007;134:233–236. doi: 10.1242/dev.02729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris AN, Macdonald PM. Aubergine encodes a Drosophila polar granule component required for pole cell formation and related to eIF2C. Development. 2001;128:2823–2832. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forrest KM, Clark IE, Jain RA, Gavis ER. Temporal complexity within a translational control element in the nanos mRNA. Development. 2004;131:5849–5857. doi: 10.1242/dev.01460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bramham CR, Wells DG. Dendritic mRNA: transport, translation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:776–789. doi: 10.1038/nrn2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mili S, Moissoglu K, Macara IG. Genome-wide screen reveals APC-associated RNAs enriched in cell protrusions. Nature. 2008;453:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature06888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavis ER, Lehmann R. Localization of nanos RNA controls embryonic polarity. Cell. 1992;71:301–313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90358-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalby B, Glover DM. 3′ non-translated sequences in Drosophila cyclin B transcripts direct posterior pole accumulation late in oogenesis and peri-nuclear association in syncytial embryos. Development. 1992;115:989–997. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen F, Barkett M, Ram KT, Quintanilla A, Hariharan IK. Biological characterization of Drosophila Rapgap1, a GTPase activating protein for Rap1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12485–12490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavis ER, Curtis D, Lehmann R. Identification of cis-acting sequences that control nanos RNA localization. Dev Biol. 1996;176:36–50. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.