Abstract

Objective To determine the optimal range of increase in haemoglobin concentration with treatment with erythropoietins that is safe and is not associated with mortality.

Design Retrospective cohort study. The analysis was adjusted for several covariables with Cox regression analysis with spline functions. Use of erythropoietins, haemoglobin concentration, and covariables were included in a time varying manner; variable selection was based on the purposeful selection algorithm.

Setting Transplantation centres in Austria.

Participants 1794 renal transplant recipients recorded in the Austrian Dialysis and Transplant Registry who received a transplant between 1 January 1992 and 31 December 2004 and survived at least three months.

Main outcome measures Survival time and haemoglobin concentration after treatment with erythropoietins.

Results The prevalence of use of erythropoietins has increased over the past 15 years to 25%. Unadjusted extended Kaplan-Meier analysis suggests higher mortality in patients treated with erythropoietins, in whom 10 year survival was 57% compared with 78% in those not treated with erythropoietins (P<0.001). In the treated patients there were 5.4 events/100 person years, compared with 2.6 events/100 person years in those not treated (P<0.001). After adjustment for confounding by indication, comorbidities, comedication, and laboratory readings, haemoglobin concentrations >125 g/l were associated with increased mortality in treated patients (hazard ratio 2.8 (95% confidence interval 1.0 to 7.9) for haemoglobin concentration 140 g/l v 125 g/l), but not in those not treated (0.7, 0.4 to 1.5). When haemoglobin concentrations were 147 g/l or above, patients treated with erythropoietins showed significantly higher mortality than those who were not treated (3.0, 1.0 to 9.4).

Conclusion Increasing haemoglobin concentrations to above 125 g/l with erythropoietins in renal transplant recipients is associated with an increase in mortality. This increase was significant at concentrations above 140 g/l.

Introduction

According to the Transplant European Survey on Anemia Management (TRESAM), which analysed data from 72 transplant centres in 16 countries, 38.6% of renal transplant patients are anaemic—that is, their serum haemoglobin concentration is ≤120 g/l in females and ≤130 g/l in males.1 One in five severely anaemic patients, defined as haemoglobin concentration ≤100 (females) or ≤110 g/l (males), respectively, received treatment with erythropoietins. Furthermore, there was a strong correlation between graft function and anaemia and use of erythropoietins. Of the patients with a serum creatinine concentration >176.8 μmol/l 60% were anaemic compared with 29% of those with concentrations ≤176.8 μmol/l (P<0.01).

Until the first clinical trials were stopped because of an unexplained higher mortality rate in patients treated with erythropoietins, this treatment was considered safe and effective in correcting anaemia in many indications, including renal anaemia.

Two studies in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease found a higher mortality or more cardiovascular events in patients in whom the haemoglobin concentration had been normalised with erythropoietins.2 3 In the CHOIR study by Singh and colleagues, 1432 patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3 or 4 were randomly assigned to receive doses of erythropoietins aimed at achieving target haemoglobin concentrations of 135 g/l or 113 g/l and followed for a median of 16 months.2 Of the 222 composite events, which included death, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure, 125 occurred in the higher concentration group and 97 in the lower concentration group (hazard ratio 1.34, 95% confidence interval 1.03 to 1.74; P=0.03).

The CREATE trial by Druecke and coworkers investigated 603 patients with chronic kidney disease stage 4 for three years.3 Participants were randomised to target haemoglobin concentration ranges with erythropoietins of 130-150 g/l or 105-115 g/l. Fifty eight cardiovasulcar events occurred in the higher concentration arm and 47 in the lower concentration arm (P=0.20).

A randomised study of use of erythropoietins in patients with end stage renal disease treated by haemodialysis was published in 1998 and the follow-up reported as a comment in 2008.4 5 The authors found that more patients died and had non-fatal cardiac infarction in the group randomised to a packed cell volume of 0.42 with erythropoietins compared with the group with a packed cell volume of 0.30.

In 2003 the first clinical trials investigated whether correction of anaemia with erythropoietins could improve outcome of curative radiotherapy among patients with head and neck cancer but found an increase in mortality.6 7 Similarly, patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving first line chemotherapy who were treated with 40 000U epoetin alfa weekly exhibited a higher death rate than patients who received placebo.8 The main concern in oncological studies was that erythropoietins were associated with tumour progression and mortality. The situation is different in renal patients, in whom the main causes of death are cardiovascular events.

About half of all prevalent patients with terminal failure of their native kidneys receive a renal transplant. Nearly all recipients of a renal allograft, however, exhibit impaired glomerular filtration rates, and the 39% rate of anaemia is thus not surprising. It remains unclear whether the findings on target haemoglobin concentrations and treatment with erythropoietins in patients with chronic kidney disease (CREATE, CHOIR) and haemodialysis patients (Normal Hematocrit Study) also apply to renal transplant recipients. The main reported advantage of erythropoietins and anaemia correction was a better quality of life in the domains of physical activity.9 Transplant patients are more active and thus would probably derive special benefit from correction of anaemia in terms of physical functioning.

As there is no randomised controlled trial underway nor is it likely that there will be one done in the near future we conducted a cohort study in a well maintained national database. We investigated whether higher achieved haemoglobin concentrations with erythropoietins are associated with increased mortality in renal transplant patients.

Methods

Patient population

We used data from patients recorded in the Austrian (OEsterreichisches) Dialysis and Transplant Registry (OEDTR) and Eurotransplant database who received a renal allograft between 1 January 1992 and 30 September 2004 and survived at least three months. Patients were followed up until 31 December 2004 because thereafter prescriptions for erythropoietins and target ranges changed in renal transplant patients because of the availability of results from the CHOIR and CREATE studies of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. The registry was established by the Austrian Society of Nephrology in 1970 and has almost complete follow-up; only 17 patients have been lost since 1990. The Eurotransplant database was established in 1968 and holds complete entries of organ donor characteristics from transplants performed in the Eurotransplant region.

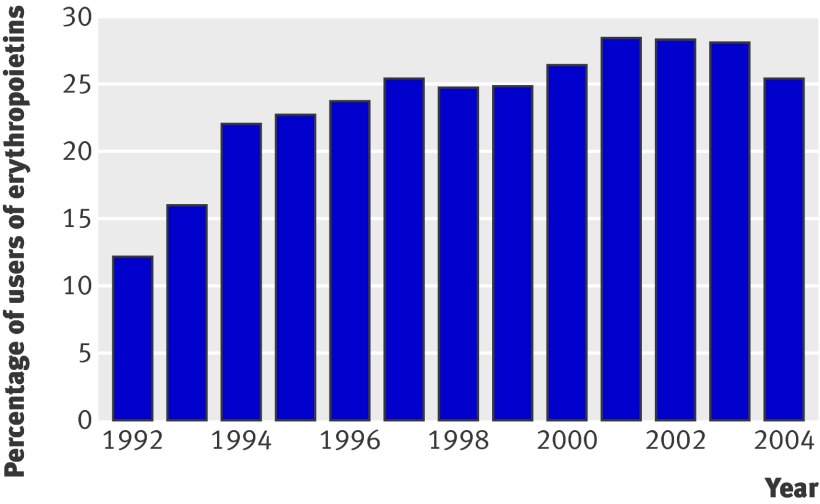

Our sample comprised 1794 patients and an equal number of grafts because we analysed only the first transplant. Before 1992 almost no patients received treatment with erythropoietins (fig 1). After 2004, the prescription pattern of erythropoietins changed because of available data from abstracts of randomised controlled trials in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients and therefore, despite availability of data on survival status and comorbidities up to 2008, we used the time range only up to the end of 2004 for analysis.

Fig 1 Percentage of users of erythropoietins by year. Percentage for year x was computed as total time of use in year x divided by total time at risk in year x

Variables and definitions of variables

All variables recorded in the database are annually updated and are listed in the appendix (see bmj.com). Continuous variables entered the analysis as time dependent with their median values per calendar year. These median values were interpolated by using linear regression within patients. Arterial hypertension was defined as mean arterial blood pressure >107 mm Hg or prescription of at least one antihypertensive drug. Patients were classified as having coronary heart disease if they had unstable angina or a myocardial infarction or if coronary stenosis was documented by angiography or radioisotopic techniques. Heart failure, vascular disease, and diabetes were defined by the attending physician.

We defined acute rejection confirmed by biopsy and chronic allograft nephropathy according to Banff 93 and 97 criteria, respectively.10 11 A total of 3546 biopsies were obtained within the study period. Banff criteria were initially not applied to 248 biopsies performed before 1 January 1994. One of the investigators reclassified these biopsies according to the Banff 97 criteria. Acute rejection confirmed by biopsy was defined as Banff borderline and higher grades/types of cellular rejection. Diagnosis and grading of lesions of biopsies in native kidneys and of the donor kidney before transplantation was performed according to the World Health Organization classification.12

Data on immunosuppressive regimens were gathered annually and classified into four groups: the standard immunosuppressive regimen was defined as triple therapy with corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and a calcineurin inhibitor (applied for 27.2% of total graft life); triple therapy with corticosteroids, azathioprine, and a calcineurin inhibitor (24.0% of graft life); all regimens without corticosteroid (13.9% of graft life); and immunosuppression without calcineurin inhibitors (19.8% of graft life) or other (15.1% of graft life). Induction treatment with a polyclonal antibody was performed in 0.092% of total graft life. IL-2 antibody induction was used infrequently (<1%).

Outcomes

The length of a patient’s survival was defined as the time from the first kidney transplantation until death or a second kidney transplantation or the end of the study (31 December 2004), whichever came first, conditional on survival to three months. Only death was counted as event.

Characteristics of patients at the time of transplantation were described by mean and standard deviation, by median and interquartile range, or by frequency and percentage for normally distributed variables, non-normally distributed variables, and categorical variables, respectively. We used t tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests to compare these characteristics between patients who did or did not receive erythropoietins at any time after transplantation.

We computed extended Kaplan-Meier curves (taking into account time varying group membership of individuals) to compare the survival of patients who did and did not receive erythropoietins.13

Multivariable Cox regression was used to model the association of use of erythropoietins and haemoglobin concentration (both time dependent) on survival.14 As the interaction of erythropoietins and haemoglobin concentration must be assumed to be non-linear, we used restricted cubic splines with five knots placed at the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th centiles for haemoglobin concentration.15 We assessed results by depicting the hazard ratio of haemoglobin concentration compared with a reference concentration of 125 g/l in those who did and did not receive erythropoietins and compared those who did and did not receive erythropoietins at various haemoglobin concentrations. The analysis was further adjusted by variables that either proved significant in a multivariable model (P<0.05) or changed the log hazard ratio of erythropoietins or haemoglobin concentration by more than 25% if we excluded those variables from the analysis (purposeful selection algorithm).16 We assumed that any variables not selected will not have had a relevant impact on our conclusions. All variables (except baseline variables) were entered as time dependent. Occasionally missing values of covariates were replaced in a multiple imputation analysis, which was accompanied by an analysis of sensitivity of the assumption of randomly missing values (see appendix on bmj.com). Five imputed versions of the dataset were generated, with results computed for each of those datasets; results were then combined with Rubin’s rules.17 The adequacy of the multiple imputation approach was underlined by the compatibility of its results to those of the complete cases only analysis. The higher number of events in the multiple imputation analysis, however, leads to a higher stability of results and better control of confounding compared with the complete cases only analysis. Included baseline covariates were primary indication for transplantation (diabetes, immune mediated, polycystic kidney disease, other), age at transplantation, year of transplantation, time on dialysis, cold ischaemia time, age of donor, and sum of HLA mismatches. Time dependent variables were number of blood pressure lowering drugs, peripheral or cardiovascular diseases, coronary heart disease, heart failure, mean arterial pressure, cholesterol concentration, type of immunosuppressive treatment, presence of diabetes, and dialysis status (functioning graft or graft not functioning and patient needs dialysis again). In the final model, we investigated the linearity assumption of continuous variables by likelihood ratio tests of a model using restricted cubic splines for these variables against a model with the variable entering as linear. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by testing an interaction of each variable with log of time. Interactions of variables were tested by including pair-wise product interaction terms. These model assumptions tests were performed by controlling a false discovery rate of 5%.18 For all other hypothesis tests we considered P<0.05 as significant, and all tests were two sided. All statistical computations were done with SAS System V9.2 (2008, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All graphics were produced with the R software (www.r-project.org).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study patients at the time of transplantation, stratified for use of erythropoietins at any time during follow-up. Characteristics associated with erythropoietins were older donor, female recipient, lower haemoglobin concentration, presence of hypertension, severity of hypertension (as measured by number of prescribed blood pressure lowering drugs and arterial pressure), higher cholesterol concentration, chronic allograft nephropathy, and cadaveric donor. Patients who received erythropoietins were also more likely to have experienced acute rejection confirmed by biopsy (46% v 30%). In these patients it is impossible to ascertain exactly whether such rejection occurred before or after use of erythropoietins. In all further analysis, we analysed use of erythropoietins by current prescription, which allows for individuals who switch from use to non-use (n=314, 18%) or vice versa (n=284, 16%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at day of transplantation, classified by use of erythropoietins. Values are means (SD), medians (interquartile range), or numbers (percentages) as shown

| Variable | Erythropoietins | No erythropoietins | P value | No of patients (erythropoietins /no erythropoietins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation (years) | 48.6 (15.0) | 48.7 (16.4) | 0.889 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Donor age (years) | 47.1 (15.3) | 42 (15.8) | <0.001 | 1597 (774/823) |

| Female donor | 331 (42.5%) | 347 (42%) | 0.829 | 1606 (779/827) |

| Female recipient | 350 (44.9%) | 281 (34%) | <0.001 | 1606 (779/827) |

| Years on dialysis before transplantation | 1.8 (0.9-3.1) | 1.8 (0.9-3) | 0.871 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Year of transplantation | 1998 (1995-2001) | 1999 (1995- 2002) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Body weight (kg) | 71.3 (16) | 71.5 (17.9) | 0.837 | 1224 (575/649) |

| Haemoglobin concentration (g/l) | 100 (91-110) | 105 (96-116) | <0.001 | 1572 (752/820) |

| STRF | 191 (156-227) | 192.1 (160-232.8) | 0.388 | 1073 (545/528) |

| TRFS | 24.2 (16.4-32.8) | 23.6 (16.1-32.4) | 0.431 | 1056 (538/518) |

| Panel reactive antibodies | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-4) | 0.728 | 1596 (779/817) |

| Sum of HLA mismatches | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.3) | 0.239 | 1542 (756/786) |

| Cold ischemia time (days) | 16.4 (8.4) | 16.8 (8) | 0.332 | 1408 (694/714) |

| Type of immunosuppression: | ||||

| S+MMF+CNI | 180 (22.4) | 188 (19) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| S+AZA+CNI | 153 (19) | 125 (12.6) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| S-free* | 23 (2.9) | 12 (1.2) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Other† | 449 (55.8) | 664 (67.1) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Induction therapy (ATG) | 188 (23.4) | 114 (11.5) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| CNI based | 415 (80.7) | 478 (83.7) | 0.200 | 1085 (514/571) |

| Hypertension | 730 (90.7%) | 709 (71.7%) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| No of antihypertensive drugs prescribed | 2 (1-4) | 2 (0-3) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Systolic arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 140.3 (51.1) | 118 (52) | <0.001 | 1117 (513/604) |

| Diastolic arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 82.2 (33.6) | 70.2 (41.3) | <0.001 | 1118 (513/605) |

| Cholesterol concentration (mmol/l) | 5.26 (1.64) | 5.10 (1.46) | 0.046 | 1523 (736/787) |

| Coronary heart disease | 132 (27.3%) | 186 (29.5%) | 0.410 | 1114 (484/630) |

| Heart failure | 90 (18.6%) | 107 (17%) | 0.485 | 1114 (484/630) |

| Any heart disease | 214 (45.1%) | 283 (46.9%) | 0.560 | 1077 (474/603) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 74 (16.1%) | 70 (12%) | 0.058 | 1045 (461/584) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 110 (23.9%) | 132 (22.6%) | 0.632 | 1045 (461/584) |

| Any vascular disease | 153 (34.2%) | 164 (29.9%) | 0.149 | 997 (448/549) |

| Biopsy confirmed acute rejection | 366 (46%) | 250 (29.5%) | <0.001 | 1642 (795/847) |

| Chronic allograft nephropathy | 164 (20.4%) | 75 (7.6%) | <0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Cadaveric donor | 736 (91.4%) | 855 (86.5%) | 0.001 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Diabetes | 233 (28.9%) | 299 (30.2%) | 0.552 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Primary indication for transplantation: | ||||

| Diabetes | 166 (20.6%) | 249 (25.2%) | 0.023 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Immune mediated | 102 (12.7%) | 121 (12.2%) | 0.781 | 1794 (805/989) |

| PCKD | 90 (11.2%) | 124 (12.5%) | 0.378 | 1794 (805/989) |

| Other or unknown | 444 (55.2%) | 485 (49.0%) | 0.010 | 1794 (805/989) |

ATG=antithymocyte globulin; STRF=serum transferrin concentration; TRFS=transferrin saturation; S+MMF+CNI=triple therapy with corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, and calcineurin inhibitor; S+AZA+CNI=triple therapy with corticosteroids, azathioprine, and CNI.

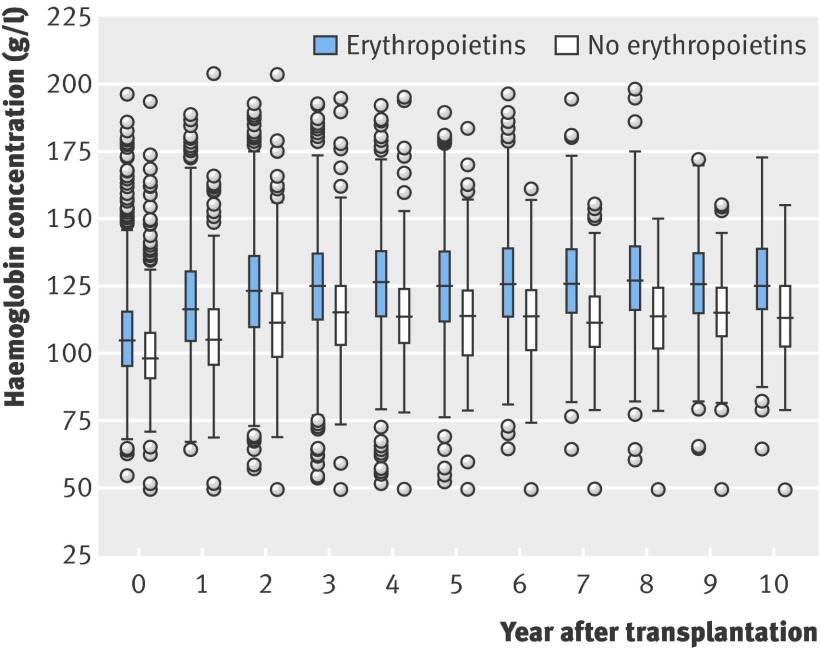

The median follow-up time was 5.6 years (interquartile range 3.0-8.7 years). Figure 1 shows the percentage of use of erythropoietins during the years under investigation. We notice increasing prevalence of erythropoietins from 1992 (12%) to 2001 (28%), and a constant use thereafter. Figure 2 shows haemoglobin concentrations over follow-up, stratified for use of erythropoietins.

Fig 2 Haemoglobin concentration v time after transplantation, showing median (horizontal centre bar), 25th and 75th centiles (lower and upper ends of box), and values below or above interquartile range

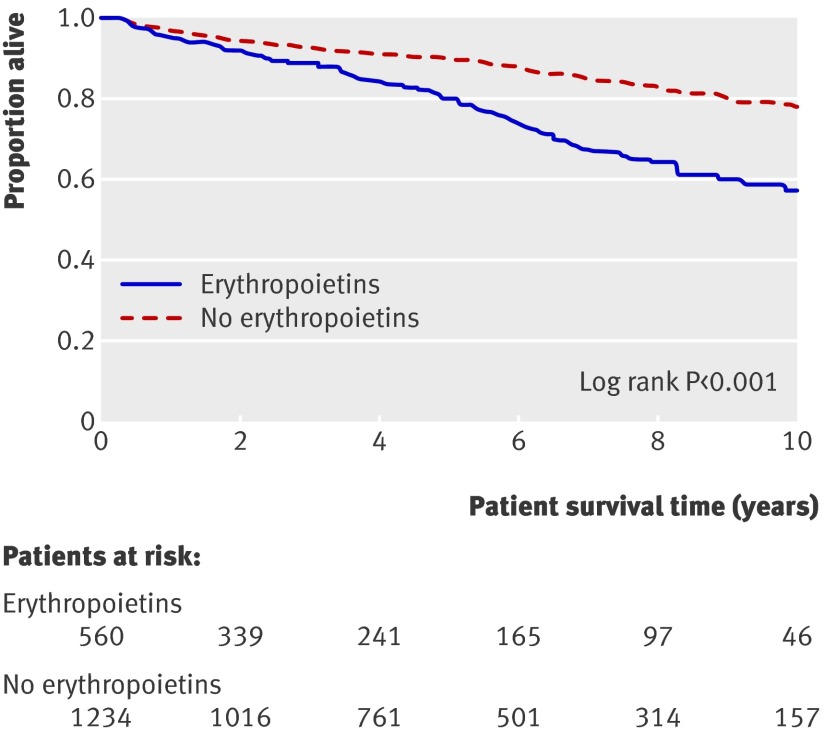

During follow-up, 345 of the 1794 patients died; 59 died during the first 90 days after transplantation. The overall absolute mortality rates per 100 person years were 5.4 for those who received erythropoietins and 2.6 for those who did not. The mortality rates for cardiovascular, malignancy, and infection related death were numerically higher in those who received erythropoietins compared with those who did not (events per 100 person years were 1.4 v 0.8 for cardiovascular events; 0.4 v 0.3 for malignancy; 1.7 v 0.7 for infection). In total, 178 patients experienced graft failure (18 during the first 90 days) and returned to dialysis. Figure 3 shows extended Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival probabilities (allowing for individuals switching groups) stratified for use of erythropoietins.

Fig 3 Extended Kaplan-Meier plot of patients’ survival (P<0.001)

Using multivariable Cox regression, we assessed the association between haemoglobin concentration and use of erythropoietins on survival. The purposeful selection algorithm identified several variables to include in the model. These comprised dialysis status, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cholesterol concentration, type of immunosuppressive regimen, diabetes status, age at transplantation, and cold ischaemia time.

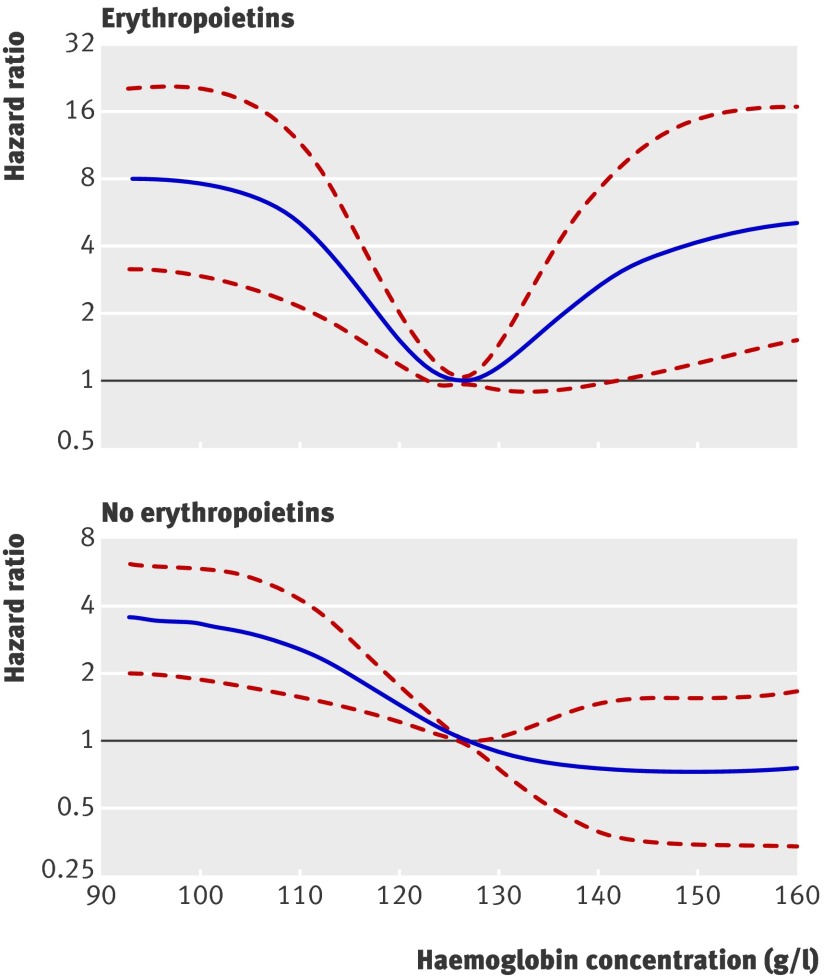

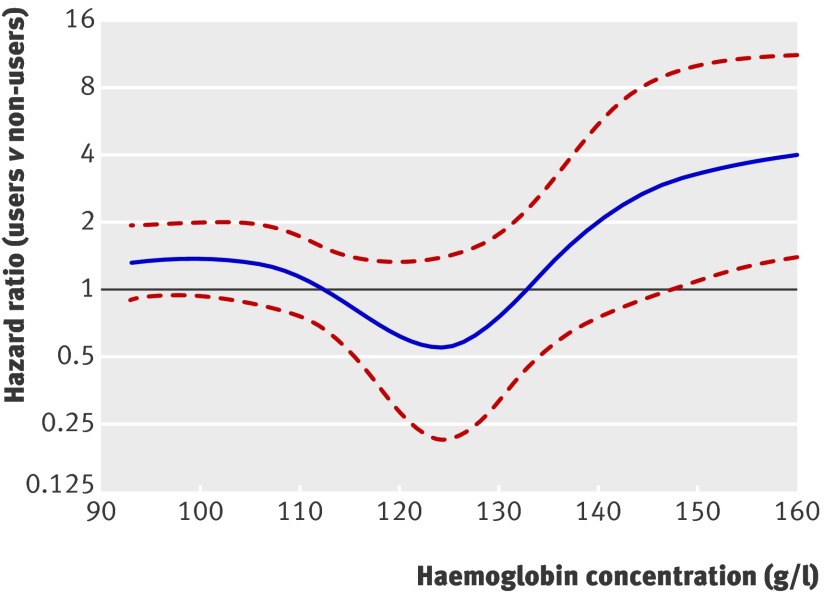

Figure 4 shows the hazard ratios associated with various haemoglobin concentrations against a reference level of 125 g/l for those who did and did not receive erythropoietins. In both groups, haemoglobin concentrations <125 g/l were correlated with increased risk of mortality. In patients who did not receive erythropoietins, higher concentrations led to reduced risk. In those who did receive erythropoietins, however, we saw the opposite: at haemoglobin concentrations >140 g/l, we noted a significantly increased risk. Comparing these patients with those who did not receive erythropoietins, given they exhibit similar haemoglobin concentrations (fig 5), we found no significant difference in mortality with haemoglobin concentrations up to about 147 g/l, but with higher concentrations recipients had significantly higher risk than non-recipients. Table 2 summarises these findings.

Fig 4 Adjusted hazard ratio for haemoglobin concentration (reference level 125 g/l). Results obtained by multivariable Cox regression with restricted cubic splines with five knots for haemoglobin concentration, adjusted for dialysis status, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cholesterol concentration, immunosuppressive regimen, diabetes status, age at transplantation, and cold ischaemia time

Fig 5 Adjusted hazard ratio at various haemoglobin concentrations for patients who did and did not use erythropoietins. Hazard ratios >1 indicate higher risk for those who received erythropoietins. Results were obtained by multivariable Cox regression with restricted cubic splines with five knots for haemoglobin concentration, adjusted for dialysis status, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cholesterol concentration, immunosuppressive regimen, diabetes status, age at transplantation, and cold ischaemia time

Table 2.

Adjusted* hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from multivariable Cox regression including interaction of use of erythropoietins and haemoglobin concentration (with restricted cubic splines with five knots)

| Haemoglobin concentration (g/l) | No erythropoietins | Erythropoietins | Erythropoietins v no erythropoietins |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95 | 3.5 (2.0 to 6.0) | 8.0 (3.1 to 20.6) | 1.4 (0.9 to 1.9) |

| 110 | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.0) | 4.7 (2.1 to 10.5) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) |

| 125 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.5) |

| 140 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.5) | 2.8 (1.0 to 7.9) | 2.2 (0.8 to 6.0) |

| 155 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.6) | 4.7 (1.4 to 16.2) | 3.8 (1.3 to 10.9) |

*Adjusted for dialysis status, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cholesterol concentration, type of immunosuppressive regimen, use of calcineurin inhibitors, diabetes status, age at transplantation, cold ischaemia time.

Several sensitivity analyses assessed the impact of the model’s assumptions on our conclusions. In particular, we checked the assumption of randomly missing values in the multiple imputation procedure, non-linear effects of metric variables, and time dependent effects of variables, using a reduced or extended set of covariables in the multivariable Cox model, and the impact of including deaths during the first 90 days in the analysis. Detailed reports of these additional analyses are given in the appendix on bmj.com. None of these sensitivity analyses led to any substantial changes in our conclusions.

Discussion

Regardless of treatment with erythropoietins, anaemia in kidney transplant recipients is associated with an increased risk of mortality. The hazard of dying decreases numerically with increasing haemoglobin concentration above the reference value of 125 g/l in those who do not receive erythropoietins but increases when higher concentrations are achieved with erythropoietins. The cut-off where this difference in mortality reached significance was a haemoglobin serum concentration of >140 g/l (lower 95% confidence interval); the point estimate of the hazard ratio started to increase already at a haemoglobin concentration of 125 g/l.

Winkelmayr and Chandraker recently summarised the enigma of post-transplant anaemia.19 Their conclusion was that because of the lack of large, well designed, prospective studies, the consequences of anaemia, the response to treatment, and the cost effectiveness of treatment in the post-transplantation setting remain poorly understood. In a previous study the same authors concluded that post-transplant anaemia is prevalent and undertreated in kidney transplant recipients.20

Comparison with other studies

Our results fit well with the data obtained in large randomised controlled trials in patients with chronic kidney disease and haemodialysis patients in whom a target haemoglobin concentration of 135 g/l (CHOIR) and 130-150 g/l (CREATE) or a normal versus a low packed cell volume of 0.42 versus 0.30 (Normal Hematocrit Study) caused an increase or at least no decrease in cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.

Observational studies have previously shown that anaemia after renal transplantation, defined as haemoglobin concentration below 130 g/l in males and 120 g/l in females, is associated with higher mortality and graft loss compared with non-anaemic patients.21 22 These studies, however, did not address the main issue of treating anaemia with erythropoietins, and the association of achieved haemoglobin concentrations with hard outcomes such as mortality. Iron deficiency contributes to post-transplant anaemia.19 Measures of iron status, such as transferring and transferrin saturation of ferritin, were available and were no different between groups but, according to Lorenz and colleagues, do not predict post-transplant anaemia.23

Study limitations and strengths

Our present observational study has some intrinsic limitations by design. We dealt with confounding of the association of haemoglobin concentrations and use of erythropoietins with survival by using techniques such as the purposeful selection algorithm. Unmeasured confounding was addressed by inclusion of as many potentially relevant covariates as possible. As our aim was not to compare those who were or were not treated with erythropoietins but rather to assess the association of achieved haemoglobin concentration with survival, recently developed techniques to control confounding and assess causality of effects, such as marginal structural models, were not applicable.24 Therefore, as in all non-randomised trials, we could not confirm a causal relation. Furthermore, the OEDTR database does not have information on dose of erythropoietins and specific product and thus we cannot speculate on what might have caused this increased risk of mortality. A potential dilution effect might have occurred because of patients who received erythropoietins but did not respond. In the absence of a randomised controlled trial, however, it is impossible to quantify this dilution effect. Recent experimental data in patients not undergoing transplantation suggest that high doses of erythropoietins might cross activate growth receptor thus leading to tumour progression and potential cardiovascular events.25

Although all covariates entered the analysis as time dependent, there was no general follow-up scheme at which measurements were taken, which is typical for observational retrospective studies. Some data, such as data on drug prescription or comorbidities, were available only on an annual basis. For laboratory variables, typically several measurements a year were available. We paid regard to varying number of follow-up measurements between patients by using the median value per calendar year. Some authors, such as Brown and colleagues,26 proposed analysis of longitudinal measurements and survival in a so called joint regression analysis. To our knowledge, such techniques have not yet been used to analyse interactions of several time dependent variables (as in our study) and are still far from being suitable for routine analyses. Moreover, in 20 variables on average 19.5% of the values were missing. We addressed this problem with different analytical strategies including complete cases only and multiple imputations including sensitivity analysis. Results were stable over these different analyses, suggesting robust findings. The occurrence of missing values, however, must be seen as a limitation. In the absence of a randomised controlled trial our analysis provides the only evidence on the association of use of erythropoietins above a certain haemoglobin concentration and mortality in renal transplant patients.

Conclusions and policy implications

In summary we found that increasing haemoglobin concentration to above 140 g/l with treatment with erythropoietins in renal transplant recipients is associated with an increase in mortality. Because of the study design we cannot confirm a causal relation, but, in analogy to interventional studies in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, we consider that renal transplant recipients with a haemoglobin concentration over 125 g/l should not be given erythropoietins.

What is already known on this topic

The prevalence of anaemia after kidney transplantation approaches 40% and about 20% of severely anaemic patients (haemoglobin ≤110 g/l in males and 100 g/l in females) are treated with erythropoietins

Recent data suggest that use of erythropoietins might actually increase mortality under some circumstances

What this study adds

Increasing haemoglobin concentrations to >125 g/l with erythropoietins in renal transplant recipients is associated with an increase in mortality, which was significant at >140 g/l

The risk of death at an achieved haemoglobin concentration of 140 g/l v 125 g/l was 2.8 with erythropoietins and 0.7 without

Because of the study design a causal relation cannot be confirmed

We thank the administrators and all contributors of the Austrian Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

Contributors: GH and RO performed statistical analysis and wrote the paper. AK and WHH wrote part of the paper and maintained the database. RO is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (P-18325-B13 to R.O.) and the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4018

References

- 1.Vanrenterghem Y, Ponticelli C, Morales JM, Abramowicz D, Baboolal K, Eklund B, et al. Prevalence and management of anemia in renal transplant recipients: a European survey. Am J Transplant 2003;3:835-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, et al. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2085-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drueke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, et al. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2071-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med 1998;339:584-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besarab A, Goodkin DA, Nissenson AR. The normal hematocrit study—follow-up. N Engl J Med 2008;358:433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henke M, Laszig R, Rube C, Schafer U, Haase KD, Schilcher B, et al. Erythropoietin to treat head and neck cancer patients with anaemia undergoing radiotherapy: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2003;362:1255-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overgaard J, Hoff C, Sand Hansen H, Specht L, Overgaard M, Grau C, et al. Randomized study of the importance of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (Aranesp) for the effect of radiotherapy in patients with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck HNSCC)—the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group DAHANCA 10 randomized trial. Eur J Cancer Suppl 2007;5:7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leyland-Jones B, Semiglazov V, Pawlicki M, Pienkowski T, Tjulandin S, Manikhas G, et al. Maintaining normal hemoglobin levels with epoetin alfa in mainly nonanemic patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy: a survival study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5960-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eschbach JW, Abdulhadi MH, Browne JK, Delano BG, Downing MR, Egrie JC, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin in anemic patients with end-stage renal disease. Results of a phase III multicenter clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1989;111:992-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solez K, Axelsen RA, Benediktsson H, Burdick JF, Cohen AH, Colvin RB, et al. International standardization of criteria for the histologic diagnosis of renal allograft rejection: the Banff working classification of kidney transplant pathology. Kidney Int 1993;44:411-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 1999;55:713-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churg J, Sobin LH. Benign nephrosclerosis. In: Churg J, ed. Renal disease—classification and atlas of glomerular diseases. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin, 1982:211-24.

- 13.Snappin S, Jiang Q, Iglewicz B. Illustrating the impact of a time-varying covariate with an extended Kaplan-Meier estimator. Am Stat 2005;59:301-7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Soc B 1972;34:187-220. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzl H, Kaider A. Gaining more flexibility in Cox proportional hazards regression models with cubic spline functions. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1997;54:201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis. Regression modeling of time to event data. New York, NY: Wiley, 1999.

- 17.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley, 1987.

- 18.Benyamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B 1995;57:289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkelmayer WC, Chandraker A. Posttransplantation anemia: management and rationale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:S49-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkelmayer WC, Kewalramani R, Rutstein M, Gabardi S, Vonvisger T, Chandraker A. Pharmacoepidemiology of anemia in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:1347-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamar N, Rostaing L. Negative impact of one-year anemia on long-term patient and graft survival in kidney transplant patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation 2008;85:1120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molnar MZ, Czira M, Ambrus C, Szeifert L, Szentkiralyi A, Beko G, et al. Anemia is associated with mortality in kidney-transplanted patients—a prospective cohort study. Am J Transplant 2007;7:818-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz M, Kletzmayr J, Perschl A, Furrer A, Horl WH, Sunder-Plassmann G. Anemia and iron deficiencies among long-term renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:794-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology 2000;11:561-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AK. The controversy surrounding hemoglobin and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: what should we do now? Am J Kidney Dis 2008;52(6 suppl):S5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown ER, Ibrahim JG, DeGruttola V. A flexible B-spline model for multiple longitudinal biomarkers and survival. Biometrics 2005;61:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]