Abstract

Background

Racial/ethnic health care disparities are well described in people living with HIV/AIDS, although the processes underlying observed disparities are not well elucidated.

Methods

A retrospective analysis nested in the UAB 1917 Clinic Cohort observational HIV study evaluated patients between August 2004 and January 2007. Factors associated with appointment non-adherence, a proportion of missed outpatient visits, were evaluated. Next, the role of appointment non-adherence in explaining the relationship between African American race and virologic failure (plasma HIV RNA >50 copies/mL) was examined using a staged multivariable modeling approach.

Results

Among 1,221 participants a broad distribution of appointment non-adherence was observed, with 40% of patients missing at least 1 in every 4 scheduled visits. The adjusted odds of appointment non-adherence were 1.85 times higher in African American patients compared to Whites (95%CI=1.61–2.14). Appointment non-adherence was associated with virologic failure (OR 1.78; 95%CI=1.48–2.13), and partially mediated the relationship between African American race and virologic failure. African Americans had 1.56 times the adjusted odds of virologic failure (95%CI=1.19–2.05), which declined to 1.30 (95%CI=0.98–1.72) when controlling for appointment non-adherence, a hypothesized mediator.

Conclusions

Appointment non-adherence was more common in African American patients, associated with virologic failure, and appeared to explain part of observed racial disparities in virologic failure.

Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in health care (e.g., antiretroviral medication receipt) and clinical outcomes (e.g., mortality) are well described in people living with HIV/AIDS,1–3 although the processes underlying observed disparities have not been well elucidated. Recently, there has been a call for the research community to move beyond descriptive studies in an effort to gain a better understanding of the root causes contributing to health care disparities.4–6 It has been argued that investigation of pathways mediating disparities has been limited thus impeding intervention development. While such pathways are likely to be complex and multi-faceted, a better understanding of contributing factors is needed to inform evidence-based interventions that will effectively address health care disparities.4, 5, 7

One particularly important pathway is access to care, which has long been recognized as an important factor contributing to health care disparities.7–11 Although insurance coverage is a known contributor, the Institute of Medicine reported that disparities in the quantity and quality of care exist even for patients with similar insurance coverage.8 To date, the role of detailed measures of access to care as a component of the pathway contributing to disparities in health care processes and outcomes has not been extensively studied, particularly when adjusting for insurance status. One such detailed measure is adherence to scheduled outpatient appointments among patients engaged in medical care.

Appointment non-adherence, or missed outpatient appointments, are common in HIV-infected patients, and have been observed more frequently in African Americans and the uninsured.12–15 Missed visits have also been associated with a higher incidence of virologic failure and clinical disease progression including incident AIDS-defining illnesses and death.16–22 However, to our knowledge, the potential role of appointment non-adherence in contributing to racial/ethnic disparities in HIV outcomes has not been well studied. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the role of appointment non-adherence in explaining, in part, observed racial disparities in virologic failure in an outpatient HIV cohort engaged in clinical care.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) 1917 Clinic Cohort is an IRB approved HIV clinical cohort protocol for the conduct of retrospective and prospective studies that has been described previously (www.uab1917cliniccohort.org).23–25 Established in 1992, the cohort contains detailed sociodemographic, psychosocial, and clinical information from all patients receiving care at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS clinic, including over 1,500 active patients. The current study includes patients with ≥4 scheduled primary HIV care appointments occurring over a minimum of 6 months between the first and last appointment (≥6 months) at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic during a study period of 1 August 2004 – 31 January 2007. Consistent with previous research,12, 13, 26, 27 appointments “cancelled” by the patient in advance of the scheduled visit or due to hospitalization, as well as visits cancelled by the 1917 Clinic, were excluded from the scheduled appointment measure as were all subspecialty appointments at the clinic (e.g. dermatology).

Measures

Appointment non-adherence

A missed visit proportion (MVP) was calculated for all study participants as a ratio of the number of “no show” visits divided by the overall number of scheduled appointments (“arrived” and “no show”) during the study period.

ARV receipt during the study period

Consistent with prior studies,28–30 and with treatment recommendations at the time of the study,31 patients who received ARVs as well as those with a laboratory indication for ARV therapy (CD4<350 cells/mm3 and/or plasma HIV RNA>100,000 copies/mL) at any point during the study period were included in these analyses.

Virologic Failure – Failure to achieve an undetectable plasma HIV RNA (<50 copies/mL)

Among patients receiving ARVs during the study period, the last plasma HIV RNA level (viral load) obtained during the study period was evaluated and recorded as a dichotomous measure (<50 copies/mL vs. ≥50 copies/mL). The last viral load measure was chosen to evaluate the temporal role of appointment non-adherence on subsequent virologic failure. To be included in this analysis, the last viral load measure had to be obtained at least 90 days after each patient's first attended visit during the study period.

Other measures

Sociodemographic characteristics, co-morbid affective mental health disorders, substance abuse and alcohol abuse disorders as recorded in patients' medical record, and baseline CD4 count, defined as the most recent measure within +/− 90 days of the initial clinic visit during the study period were ascertained by query of the 1917 Clinic Database. Because only 29 patients (2%) belonged to a racial/ethnic group other than African American and white, these patients were excluded from analyses.

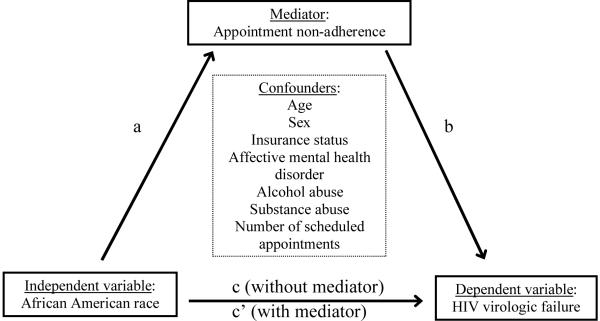

Mediation Analysis

The application of mediation methods in the evaluation of observational data has a long-standing history in the social sciences and is being employed increasingly in biomedical research.32–35 Mediation analyses allow for the evaluation of pathways through which independent variables exert an effect on dependent variables. These methods are particularly germane when studying areas not amenable to randomized studies, such as health care disparities, since they allow for the identification of relevant pathways that may be targeted when developing informed interventions. A basic approach to mediation analysis involves a three variable system in which the role of a third variable (mediator) in contributing to the relationship between an independent and dependent variable is evaluated.32–35 The current study employs this approach and evaluates the role of appointment non-adherence (mediator) in contributing to the relationship between African American race (independent variable) and HIV virologic failure (dependent variable) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Basic mediation model employed in the evaluation of appointment non-adherence as a mediator of racial disparities in HIV virologic failure (plasma HIV RNA >50 copies/mL). According to this framework, a series of steps are required to conclude that mediation has occurred: (1) variations in the level of the independent variable significantly account for variations in the mediator (path a, Table 1), (2) variations in the level of the mediator significantly account for variations in the level of the dependent variable (path b, Table 3), (3) variations in the level of the independent variable significantly account for variations in the level of the dependent variable (path c, Table 3), and (4) the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (path c', Table 3,) is included in the equation.32–35 Implicit in this framework is a temporal ordering whereby the potential mediator temporally follows the independent variable and temporally precedes the dependent variable. We believe the temporal relationship between variables is correctly defined in this study. For this study, the four steps are shown in both unadjusted analyses as well as when controlling for confounders, as displayed in the tables and described in the manuscript.

According to this framework, a series of steps are required to conclude that mediation has occurred: (1) variations in the level of the independent variable significantly account for variations in the mediator (path a), (2) variations in the level of the mediator significantly account for variations in the level of the dependent variable (path b), (3) variations in the level of the independent variable significantly account for variations in the level of the dependent variable (path c), and (4) the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (path c') is attenuated when the mediator is included in the equation.32–35 Implicit in this framework is a temporal ordering whereby the potential mediator temporally follows the independent variable and temporally precedes the dependent variable. We believe the temporal relationship between variables is correctly defined in this study. For this study, the four steps are evaluated in unadjusted analyses as well as when controlling for confounders, as described in the following section.

Statistical analysis

Association of Appointment Non-adherence with Patient Characteristics

Binomial generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with an auto-regressive correlation structure, which accounts for the correlation of multiple observations nested within each patient, were applied to generate the odds of a “no show” visit for various patient characteristics. These analyses addressed step 1 (path a) of the mediation analysis.

Predictors of Antiretroviral Medication Receipt

Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression was applied to evaluate factors associated with failure to receive ARVs. Primary analyses included patients meeting study inclusion criteria (i.e., those with ≥4 visits over ≥6 months), while sensitivity analyses were conducted using the entire clinic population who had at least one visit during the study period. Only patients treated with ARVs or with a laboratory indication for treatment were included in these analyses.

Predictors of Virologic Failure; Staged Mediation Modeling

Factors associated with virologic failure (>50 copies/mL) were initially examined with unadjusted logistic regression models (paths b and c, unadjusted analyses).

To evaluate appointment non-adherence as a covariate potentially mediating the effects of a disparity marker (i.e., African American race) on virologic failure, we used logistic regression to model virologic failure conditional on measured covariates to obtain the “total effects” (path c); and further conditional on appointment non-adherence to obtain the “direct effects” (path c') using a basic mediation modeling approach (Figure 1).32–35 The first logistic regression model included all covariates except for MVP (path c, adjusted analysis). Next, a second model including MVP was used to evaluate the role of appointment non-adherence as a mediator of virologic failure, as indicated by shifts in parameter estimates and statistical significance for the African American race variable relative to the first model (path b, adjusted analysis & path c', mediation analysis). Such mediation assessments must assume that the mediator and outcome are not themselves confounded,36, 37 and that the risk factor of interest and mediator do not interact to cause the outcome.37, 38

Finally, we calculated the mediation ratio as (c - c')/c, which represented the estimated proportion of the association between the main exposure (African American race) and the outcome (virologic failure) attributable to the mediator (appointment non-adherence).32, 39, 40 Following recommendations from Shrout and Bolger,40 we generated 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence bands for the mediation ratio based on 1,000 replicate datasets from random re-sampling with replacement (bootstrapping).

For each outcome measure, we examined interactions between the sex, race, and insurance variables and controlled for the total number of scheduled appointments in multivariable models. We also examined interactions between MVP and all other independent variables in the analysis of virologic failure. Sensitivity analyses were performed for all three outcome measures by restricting the sample to patients with ≥4 scheduled primary HIV care appointments occurring over ≥12 months, rather than the ≥6 month time period utilized for primary analyses. These analyses yielded similar results to the primary study analyses (data not shown). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.0 and STATA 10.0 SE.

Results

Among 1,503 UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic patients with scheduled appointments during the study period, 1,221 patients (81%) met study criteria and are included in this analysis. The mean age of study participants was 42.0 years, 24% were female, 47% were African American, 34% had public health insurance, and 23% were uninsured (Table 1). Half of study patients had an affective mental health disorder reported in their problem list, 19% had substance abuse disorders and 13% had alcohol abuse disorders recorded in their medical records. The mean number of scheduled appointments (“arrived” and “no show” visits only) was 9.5 per patient during the 30 month study period.

Table 1.

Overall characteristics and factors associated with poor adherence to primary HIV care appointments among 1,221 patients with at least 4 scheduled appointments over a ≥6 month time period at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic, August 2004 – January 2007.†

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD or N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) for No Show‡ | Adjusted OR (95% CI) for No Show‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.0 ± 9.2 | 0.82 (0.76–0.88)§** | 0.86 (0.80–0.93)§** |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 927 (75.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 294 (24.1) | 1.34 (1.15–1.55)** | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) |

| Race | |||

| White | 649 (53.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American | 572 (46.9) | 2.00 (1.75–2.29)** | 1.85 (1.61–2.14)** |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 519 (42.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Public | 416 (34.1) | 1.58 (1.36–1.85)** | 1.35 (1.16–1.58)** |

| Uninsured | 286 (23.4) | 1.54 (1.29–1.83)** | 1.18 (0.99–1.41) |

| Affective mental health disorder | |||

| No | 615 (50.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 606 (49.6) | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) |

| Alcohol abuse | |||

| No | 1068 (87.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 153 (12.5) | 1.26 (1.03–1.55)* | 1.22 (1.01–1.48)* |

| Substance abuse | |||

| No | 987 (80.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 234 (19.2) | 1.47 (1.25–1.73)** | 1.38 (1.17–1.63)** |

| Baseline CD4 count (cells/mm3) | |||

| ≤ 200 | 318 (26.0) | 1.35 (1.15–1.57)** | 1.12 (0.96–1.32) |

| 200 – 350 | 245 (21.1) | 1.29 (1.08–1.54)** | 1.22 (1.03–1.44)* |

| > 350 | 658 (53.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Number of total appointments scheduled† | 9.5 ± 3.7 | --- | --- |

| Missed visit proportion (MVP) ∥ | --- | --- | |

| 0% | 373 (30.6) | ||

| 0 < MVP < 25% | 355 (29.1) | ||

| 25 ≤ MVP < 50% | 332 (27.2) | ||

| 50 ≤ MVP < 75% | 143 (11.7) | ||

| 75 ≤ MVP < 100% | 18 (1.5) | ||

“No show” appointment status was modeled as the measure of poor adherence to HIV primary care appointments. All “arrived” and “no show” visits from all study participants during the study period were included in these analyses. “Cancelled” visits, appointments not attended for which a patient notified the clinic they would miss the visit or was hospitalized, were excluded.

Binomial generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with an auto-regressive correlation structure, which accounts for the correlation of multiple observations nested within each patient. Adjusted model controls for other variables with numeric values displayed in the table.

Odds ratio for 10-years increments

The missed visit proportion (MVP) is a binomial ratio of the number of “no show” visits divided by the overall number of scheduled appointments (“arrived” and “no show”) during the study period.

p<0.05

p<0.01

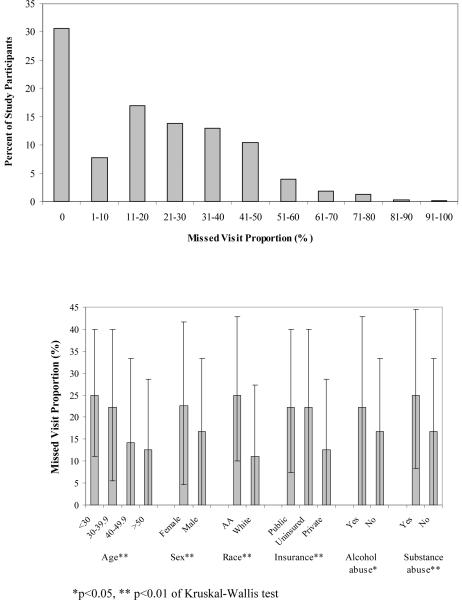

A broad distribution of appointment non-adherence was observed with 40% of patients missing at least 1 of every 4 scheduled appointments (Figure 2a). A higher median MVP was observed in younger patients, females, African Americans, patients lacking private health insurance, and those with alcohol abuse and substance abuse histories (Figure 2b). In multivariable GEE analysis, appointment non-adherence was associated with younger age, African American race (OR=1.85, 95%CI=1.61–2.14), having public health insurance, a baseline CD4 count of 200–350 cells/mm3, alcohol abuse and substance abuse disorders (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Distribution of appointment non-adherence among as measured by the missed visit proportion (MVP, 2a), and characteristics associated with MVP in bivariate analyses (1b) among 1,221 patients with at least 4 scheduled HIV primary care appointments over a ≥6 month time period at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic, August 2004 - January 2007. The median MVP and interquartile range is presented in Figure 2b and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare median MVP among study participants.

Among 1,221 study participants, 1,151 (94%) were eligible for antiretroviral treatment during the study period, which was prescribed in 96% of these patients (1,110 of the 1,151 individuals). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, only appointment non-adherence (OR=2.03 per 25% MVP, 95%CI=1.40–2.95) was associated with failure to have ARVs prescribed among treatment eligible patients (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis evaluating all patients with an attended visit during the study period (N=1,503) found that 92% of treatment eligible patients received ARVs. In multivariable analysis (excluding appointment non-adherence), African Americans (OR=1.54, 95%CI=1.00–2.39) and the uninsured (OR=1.96; 95%CI=1.16–3.3) were less likely to receive ARVs (data not shown).

Table 2.

Factors associated with failure to receive antiretroviral therapy among 1,151 ARV treatment eligible HIV primary care patients at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic, August 2004 – January 2007.

| Characteristic | ARV (n=1,110)† | No ARV (n=41)† | Crude OR (95% CI) for No ARV | Adjusted OR (95% CI) for No ARV‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.2 (9.2) | 40.1 (9.1) | 0.77 (0.55–1.09)§ | 0.95 (0.65–1.37)§ |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 850 (76.6) | 30 (73.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 260 (23.4) | 11 (26.8) | 1.20 (0.59–2.43) | 1.11 (0.52–2.38) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 604 (54.4) | 17 (41.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American | 506 (45.6) | 24 (58.5) | 1.69 (0.90–3.17) | 1.24 (0.60–2.56) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 465 (41.9) | 15 (36.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Public | 394 (35.5) | 11 (26.8) | 0.87 (0.39–1.91) | 0.75 (0.33–1.71) |

| Uninsured | 251 (22.6) | 15 (36.6) | 1.85 (0.89–3.85) | 1.42 (0.65–3.13) |

| Affective mental health disorder | ||||

| No | 555 (50.0) | 22 (53.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 555 (50.0) | 19 (46.3) | 0.86 (0.46–1.61) | 1.12 (0.57–2.20) |

| Alcohol abuse | ||||

| No | 977 (88.0) | 34 (82.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 133 (12.0) | 7 (17.1) | 1.51 (0.66–3.48) | 1.53 (0.63–3.73) |

| Substance abuse | ||||

| No | 902 (81.3) | 33 (80.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 208 (18.7) | 8 (19.5) | 1.05 (0.48–2.31) | 0.85 (0.36–2.00) |

| Number of total appointments | 9.7 (3.8) | 8.3 (3.0) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97)* | 0.90 (0.81–1.01) |

| Missed visit proportion (MVP) | 20.2 (19.6) | 35.9 (25.6) | 2.27 (1.62–3.19)∥** | 2.03 (1.40–2.95)∥** |

Data presented as N (column percent) or mean (standard deviation), ARV = antiretroviral

Multivariable logistic regression model controls for other variables displayed in the table. Model characteristics: Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic, P=0.49, c-statistic=0.73

Odds ratio for 10-years increments

Odds ratio for 25% increments

p<0.05

p<0.01

Plasma HIV RNA levels obtained at least 90 days after the first attended visit in the study period were available for 1,088 patients who received antiretroviral therapy (98%). Forty-one percent of these patients (n=448) experienced virologic failure (>50 copies/mL) at the last measure during the study period. In multivariable logistic regression analysis excluding appointment non-adherence (Table 3), younger age, African American race (OR=1.56, 95%CI=1.19–2.05), and having public health insurance were associated with virologic failure.

Table 3.

Factors associated with failure to achieve an undetectable plasma HIV RNA level (viral load (VL) <50 c/mL) among 1,088 HIV primary care patients at the UAB 1917 HIV/AIDS Clinic receiving ARV treatment, August 2004 – January 2007; staged multivariable mediation modeling.

| Characteristic | VL<50 c/mL (n=640)† | VL≥50 c/mL (n=448)† | Crude OR (95% CI) for VL≥50 c/mL | Adjusted OR (95% CI) for VL≥50 c/mL‡ | Mediation model Adjusted OR (95% CI) for VL≥50 c/mL§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.4 ± 9.2 | 40.8 ± 9.1 | 0.73 (0.64–0.84)** | 0.75 (0.65–0.87)** | 0.78 (0.68–0.91)** |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 497 (77.7) | 338 (75.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 143 (22.3) | 110 (24.6) | 1.13 (0.85–1.50) | 0.85 (0.62–1.16) | 0.82 (0.59–1.13) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 386 (60.3) | 212 (47.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| African American | 254 (39.7) | 236 (52.7) | 1.69 (1.33–2.16)** | 1.56 (1.19–2.05)** | 1.30 (0.98–1.72) |

| Insurance | |||||

| Private | 312 (48.8) | 144 (32.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Public | 194 (30.3) | 194 (43.3) | 2.17 (1.64–2.87)** | 1.82 (1.35–2.44)** | 1.62 (1.20–2.20)** |

| Uninsured | 134 (20.9) | 110 (24.6) | 1.78 (1.29–2.45)** | 1.31 (0.93–1.85) | 1.21 (0.86–1.72) |

| Affective mental health disorder | |||||

| No | 328 (51.3) | 211 (47.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 312 (48.7) | 237 (52.9) | 1.18 (0.93–1.50) | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) | 1.18 (0.90–1.54) |

| Alcohol abuse | |||||

| No | 569 (88.9) | 388 (86.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 71 (11.1) | 60 (13.4) | 1.24 (0.86–1.79) | 1.05 (0.71–1.57) | 1.00 (0.66–1.51) |

| Substance abuse | |||||

| No | 542 (84.7) | 343 (76.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 98 (15.3) | 105 (23.4) | 1.69 (1.25–2.30)** | 1.39 (0.99–1.95) | 1.27 (0.90–1.80) |

| Number of total appointments | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 10.4 ± 4.3 | 1.08 (1.04–1.11)** | 1.05 (1.01–1.09)** | 1.06 (1.02–1.10)** |

| Missed visit proportion (MVP) | 15.5 ± 16.8 | 24.7 ± 19.4 | 2.00 (1.68–2.38)** | - | 1.78 (1.48–2.13)** |

Data presented as N (column percent) or mean ± standard deviation, VL = plasma viral load

Multivariable logistic regression model controls for other variables with numeric values displayed in the table. Model characteristics: Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic, P=0.88, c-statistic=0.65

Multivariable logistic regression model controls for all variables displayed in the table. Model characteristics: Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic, P=0.96, c-statistic=0.68

∥ Odds ratio for 10-years increments

¶ Odds ratio for 25% increments

* p<0.05

p<0.01

Subsequently, MVP was added to the multivariable model to evaluate the role of appointment non-adherence as a covariate mediating the effects of a disparity marker (i.e., African American race) on virologic failure through mediation analysis (Figure 1 and Table 3).32–35 In this final model, a shift in the parameter estimate for African American race (OR=1.56 to OR=1.30) was observed, and this variable became statistically non-significant (P>0.05). Appointment non-adherence (OR=1.78 per 25% MVP, 95%CI=1.48–2.13) was significantly associated with virologic failure. The estimate of the association between African American race and virologic failure was reduced by 41% (95%CI=21–100%) after adjustment for appointment non-adherence. Notably, we did not identify significant interactions between MVP and any independent variables included in the multivariate model.

Discussion

Our study found that primary HIV care appointment non-adherence significantly contributes to racial disparities in HIV virologic failure. Missed outpatient HIV appointments were more common in African American patients (Step 1, path a), and were associated with HIV virologic failure among patients engaged in outpatient HIV treatment (Step 2, path b). Further, the magnitude of the observed relationship between African American race and virologic failure (Step 3, path c) became attenuated and statistically non-significant with the addition of a hypothesized mediator, appointment non-adherence, to the multivariable model (Step 4, path c'). Although additional factors certainly contribute, these findings suggest that interventions targeting appointment non-adherence may serve as a building block to address racial disparities in HIV virologic outcomes.

While the current study highlights the role of appointment non-adherence in contributing to racial disparities in virologic failure, we are unable to determine the root causes of missed visits among African American patients. We suspect that access to ancillary services such as transportation and case management,41, 42 patient-provider relationships,43, 44 health beliefs and distrust in the health care system may contribute.45, 46 Formative studies exploring the role of these and other factors will be critical to the development of interventions to improve appointment adherence in African Americans with HIV infection. Furthermore, future research should employ mediation methods to evaluate other pathways through which racial disparities in HIV outcomes occur, such that additional targets for intervention may be identified.

It has been noted that pathways mediating racial/ethnic health care disparities are likely to involve a complex interplay of health care, public health, and social factors.7 Clearly, much work needs to be done to better understand the intricate processes mediating health care disparities in HIV infection, and to provide confirmation of our findings and more details regarding the role of appointment non-adherence. From the health care system perspective, future studies may explore the role of differential receipt of antiretroviral medications. Among our study sample who attended ≥4 visits over ≥6 months, no difference in ARV receipt was observed along racial lines. However, evaluation of the all clinic patients with at least one visit during the study period showed that African Americans were less likely to receive ARVs when such treatment was indicated. These findings suggest the importance of retention in HIV care as it relates to racial disparities in receipt of antiretroviral therapy.

In a landmark study, Shapiro et al. identified disparities in receipt of protease inhibitors among HIV-infected African Americans in a national probability sample of people living with HIV/AIDS, which began enrollment shortly after this class of drugs became available.2 Recent studies examining racial disparities in antiretroviral receipt have yielded mixed results; some studies have identified persisting disparities while others demonstrate similar antiretroviral receipt by race/ethnicity.29, 30, 47 It is noteworthy that most of these studies, including ours, evaluate antiretroviral receipt using a cross-sectional design and focus on patients engaged in care. Effective treatment of HIV infection necessitates long-term, continuous treatment with antiretroviral medications. In addition to lower receipt of ARVs among patients with more missed visits as shown in the current study, it is expected that patients with worse appointment adherence are less likely to consistently receive antiretroviral therapy during longitudinal follow-up. We speculate that appointment non-adherence results in inferior HIV outcomes, as observed in this study, through less consistent receipt of antiretroviral medications among those with missed visits as well as worse antiretroviral medication adherence in these individuals.

Recently, increased attention has focused on linkage and retention to HIV clinical care.48–50 This expanded focus comes at a critical juncture as the number of new patients in need of HIV care is expected to increase dramatically in the coming years in response to the revised Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV testing recommendations that now advocate routine opt-out HIV testing for adults in all health care settings.51–53 Our study found clinic appointment adherence was worse in African Americans, younger patients, those with public health insurance, and patients with substance and alcohol abuse disorders. Previously we found that racial/ethnic minorities, females, and those lacking private health insurance were less likely to establish care at our clinic after calling to schedule an initial appointment.24 Collectively, these studies highlight a sobering challenge to the HIV research, policy, and outreach communities; to identify barriers and develop interventions to improve linkage and retention to clinical care among these underserved patient populations who bear a disproportionate burden of the US HIV epidemic.54 The findings from our study suggest that such interventions may play a role in attenuating HIV health care disparities.

Specific limitations may limit interpretation of our findings. As an observational study we are able to identify associations, but cannot attribute causality. As a single center, academically-affiliated HIV treatment center in the Southeast US, our findings may or may not be generalizable to other settings or patient populations. Our study included patients with 4 or more scheduled appointments occurring over 6-months or longer during the 30-month study period. As such, patients at the extreme of non-adherence, those lost to follow-up prior to accumulating 4 visits, are not included in these analyses. However, compared to patients included in this study, excluded patients (i.e., those with <4 visits over <6 months) were more likely to be African American, younger, and lacking private insurance (data not shown); sociodemographic characteristics associated with appointment non-adherence among study participants. This suggests that our study may actually underestimate the true impact of appointment non-adherence in these groups.

In summary, our study found that HIV clinic appointment adherence was worse in African Americans. Furthermore, appointment non-adherence was associated with failure to receive antiretroviral medications as well as failure to achieve an undetectable HIV viral load (<50 copies/mL) among patients receiving treatment. Finally, our study identifies a role of missed visits in contributing to racial disparities in virologic failure observed in African Americans. While other factors are certainly at play on the pathway mediating racial/ethnic HIV disparities, appointment non-adherence appears to play an important role. This study highlights the need to move beyond descriptive studies of health care disparities to identify pathways that may inform interventions to address and overcome inequities for those that bear a disproportionate burden of the US HIV epidemic.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic Cohort management team for their assistance with this project (www.uab1917cliniccohort.org).

Financial support: The UAB 1917 Clinic Cohort receives financial support from the following: UAB Center for AIDS Research (grant P30-AI27767), CFAR-Network of Integrated Clinical Systems, CNICS (grant 1 R24 AI067039-1), and the Mary Fisher CARE Fund. This study was supported by Grant Number K23MH082641 from the National Institute of Mental Health (MJM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented in part: 45th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, San Diego, CA; October 4–7, 2007 and the Society of Behavioral Medicine's 29th Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions, San Diego, California; March 26 – 29, 2008.

Citations

- 1.Levine RS, Briggs NC, Kilbourne BS, et al. Black White Mortality From HIV-Disease Before and After Introduction of HAART in 1996. Am J Public Health. 2007 Aug 29; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, et al. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Jama. 1999 Jun 23–30;281(24):2305–2315. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone VE. Optimizing the care of minority patients with HIV/AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Feb 1;38(3):400–404. doi: 10.1086/380969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancourt JR. Eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health care: what is the role of academic medicine? Acad Med. 2006 Sep;81(9):788–792. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie N. Health disparities--less talk, more action. N Engl J Med. 2005 Aug 18;353(7):727–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie N, Dubowitz T. Health disparities and access to health. Jama. 2007 Mar 14;297(10):1118–1121. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrulis DP. Access to care is the centerpiece in the elimination of socioeconomic disparities in health. Ann Intern Med. 1998 Sep 1;129(5):412–416. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-5-199809010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg JM, Power EJ. Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. Jama. 2000 Oct 25;284(16):2100–2107. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006 Jul;96(7):1300–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catz SL, McClure JB, Jones GN, Brantley PJ. Predictors of outpatient medical appointment attendance among persons with HIV. AIDS Care. 1999 Jun;11(3):361–373. doi: 10.1080/09540129947983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israelski D, Gore-Felton C, Power R, Wood MJ, Koopman C. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with medical appointment adherence among HIV-seropositive patients seeking treatment in a county outpatient facility. Prev Med. 2001 Nov;33(5):470–475. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kissinger P, Cohen D, Brandon W, Rice J, Morse A, Clark R. Compliance with public sector HIV medical care. J Natl Med Assoc. 1995 Jan;87(1):19–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palacio H, Shiboski CH, Yelin EH, Hessol NA, Greenblatt RM. Access to and utilization of primary care services among HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999 Aug 1;21(4):293–300. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199908010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, Clinton White A, et al. Retention in Care: A Challenge to Survival with HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giordano TP, White AC, Jr., Sajja P, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Apr 1;32(4):399–405. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucas GM, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in a large urban clinic: risk factors for virologic failure and adverse drug reactions. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Jul 20;131(2):81–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park WB, Choe PG, Kim SH, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: a predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007 Mar;261(3):268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rastegar DA, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR. Highly active antiretroviral therapy outcomes in a primary care clinic. AIDS Care. 2003 Apr;15(2):231–237. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000068371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins GK, Daniels B, Zheng H, Chueh H, Meigs JB, Freedberg KA. Predictors of antiretroviral treatment failure in an urban HIV clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):30–37. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248351.10383.b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valdez H, Lederman MM, Woolley I, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 protease inhibitors in clinical practice: predictors of virological outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Aug 9–23;159(15):1771–1776. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen RY, Accortt NA, Westfall AO, et al. Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Apr 1;42(7):1003–1010. doi: 10.1086/500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. Failure to establish HIV care: characterizing the“no show” phenomenon. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Jul 1;45(1):127–130. doi: 10.1086/518587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willig JH, Westfall AO, Allison J, et al. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor dosing errors in an outpatient HIV clinic in the electronic medical record era. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Sep 1;45(5):658–661. doi: 10.1086/520653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keruly JC, Conviser R, Moore RD. Association of medical insurance and other factors with receipt of antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health. 2002 May;92(5):852–857. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melnikow J, Kiefe C. Patient compliance and medical research: issues in methodology. J Gen Intern Med. 1994 Feb;9(2):96–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02600211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MH, Cook JA, Grey D, et al. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: the importance of abuse, drug use, and race. Am J Public Health. 2004 Jul;94(7):1147–1151. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R, et al. Racial and gender disparities in receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy persist in a multistate sample of HIV patients in 2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Jan 1;38(1):96–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pence BW, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Whetten K, Thielman N, Mugavero MJ. Use, Duration, and Success of Antiretroviral Therapy: The Influence of Psychosocial Characteristics and Race/Ethnicity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ace7e. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. Jama. 2006 Aug 16;296(7):827–843. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986 Dec;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS Behav. 2007 May;11(3):365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention and intervention research. NIDA Res Monogr. 1994;139:127–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Fallibility in estimating direct effects. Int J Epidemiol. 2002 Feb;31(1):163–165. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 1992 Mar;3(2):143–155. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman JS, Maclehose RF, Kaufman S. A further critique of the analytic strategy of adjusting for covariates to identify biologic mediation. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2004 Oct 8;1(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Harger GF, Roberts JM. Inflammation and triglycerides partially mediate the effect of prepregnancy body mass index on the risk of preeclampsia. Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Dec 15;162(12):1198–1206. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002 Dec;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conviser R, Pounds MB. Background for the studies on ancillary services and primary care use. AIDS Care. 2002 Aug;14(Suppl 1):S7–14. doi: 10.1080/09540120220149993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz MH, Cunningham WE, Fleishman JA, et al. Effect of case management on unmet needs and utilization of medical care and medications among HIV-infected persons. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Oct 16;135(8 Pt 1):557–565. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_1-200110160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Nov;19(11):1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Jun;21(6):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, et al. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. Am J Public Health. 2006 Apr;96(4):716–721. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Feb 1;38(2):213–218. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palacio H, Kahn JG, Richards TA, Morin SF. Effect of race and/or ethnicity in use of antiretrovirals and prophylaxis for opportunistic infection: a review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 2002 May-Jun;117(3):233–251. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.3.233. discussion 231–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-Infected Patients in Care: Their Lives Depend on It. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1500–1502. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. Aids. 2005 Mar 4;19(4):423–431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tobias C, Cunningham WE, Cunningham CO, Pounds MB. Making the connection: the importance of engagement and retention in HIV medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006 Sep 22;55(RR14):1–17. quiz CE11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mugavero MJ, Saag MS. HIV care at a crossroads: the emerging crisis in the US HIV epidemic. MedGenMed. 2007;9(1):58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saag MS. Which policy to ADAP-T: waiting lists or waiting lines? Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 15;43(10):1365–1367. doi: 10.1086/508664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Vol. 16. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2005. Also available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasrlink.htm. [Google Scholar]