Abstract

Inflammatory processes of vascular endothelial cells play a key role in the development ofatherosclerosis. We determined the anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on LPS-treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to evaluate their cardioprotective potential. Cells were pretreated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone prior to activation with LPS. Expression of COX-2, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and IL-6 production, and NF-κB activity were measured by Western blot, ELISA, and luciferase activity, respectively. Results showed that EPA, DHA, or troglitazone significantly reduced COX-2 expression, NF-κB luciferase activity, and PGE2 and IL-6 production in a dose-dependent fashion. Interestingly, low doses (10 µM) of DHA and EPA, but not troglitozone, significantly increased the activity of NF-κB in resting HUVECs. Our study suggests that while DHA, EPA, and troglitazone may be protective on HUVECs under inflammatory conditions in a dose-dependent manner. However there may be some negative effects when the concentrations are abnormally low, even in normal endothelium.

Keywords: DHA, EPA, Cyclooxygenase-2, Nuclear factor-κB, Endothelium

INTRODUCTION

The primary step in atherosclerosis is the accumulation of lipoproteins in the subendothelial matrix at specific arterial sites. Endothelial dysfunction is likely to play a major role in the initiation of atherosclerosis and may enhance disease progression by promoting inflammation, smooth-muscle-cell proliferation, platelet activation, and thrombus formation (Stary et al., 1994; Libby, 2002). A large number of epidemiologic studies, clinical trials, and experimental animal studies have shown that fish oils containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) protect against several types of cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, atherosclerosis, or hypertension (Engler et al., 2000; Abeywardena and Head, 2001; Kris-Etherton et al., 2002). Essential dietary lipids of the omega-6 and omega-3 families are the precursors of major mediators of inflammation, such as eicosanoids, that regulate the production of inflammatory cytokines and the expression of some major inflammation genes (Bagga et al., 2003). Prostaglandins and thromboxane A2 generation by the endothelium is regulated by the expression and activities of cyclooxygenases (COXs), and eicosanoid production associated with inflammatory conditions depends upon enhanced expression of COX-2. Elevated COX-2 expression has been detected in atherosclerotic lesions, suggesting that COX-2 may be involved in the pathogenesis of this disorder (Cipollone and Fazia, 2006; Massaro et al., 2008); this gene is known to be under the control of nuclear transcription factor, NF-κB. Although the protective effects of n-3 PUFAs are attributable to their direct effects on vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cell function (Engler et al., 2000; Abeywardena and Head, 2001; Kris-Etherton et al., 2002), the effect of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) on PGE2 and IL-6 production, COX-2 expression, and NF-κB activity in endothelial cells by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has not been investigated. Stimulation with LPS, a TLR4 agonist, results in a 56-fold increase in adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein mRNA expression in murine macrophages (Kazemi et al., 2005). Furthermore, the potential role of endotoxin as a pro-inflammatory mediator of atherosclerosis has been suggested (Stoll et al., 2004).

In this study, we investigated our hypothesis that DHA and EPA reduce inflammatory reactions in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) activated with LPS via a NF-κB-dependent pathway.

METHODS

Materials

Tissue culture medium 199 (M199), fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin), glutamine, and collagenase were supplied by Gibco-BRL (Rockville, MD, USA). Anti-COX-2, anti-NF-κB (p65), and anti-PPARγ antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagent was purchased from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). EPA was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA), and troglitazone was from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). All other chemicals, including DHA, were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

HUVECs were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, CA, USA), and were grown in M199 supplemented with 20% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 U/ml heparin, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 10 µg/ml streptomycin, and 50 µg/ml endothelial cell growth supplements (ECGS). Cells were cultured in 100-mm dishes and grown in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator. HUVECs were used between passages 3 and 6.

Cell treatment

HUVECs were serum-starved for 12 h in M199 medium containing 2% FBS and then treated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone, which was dissolved in DMSO. After 24 h of treatment, the PPARγ protein was measured by Western blot analysis. After 24 h of the same treatment, the cells were stimulated with LPS (10 µg/ml). Secreted PGE2 and IL-6 in the medium were measured 8 h later by ELISA, and the COX-2 protein level was determined by Western blot analysis.

Quantitative human IL-6 and PGE2 immunoassay

The level of IL-6 or PGE2 in the conditioned medium was determined using an IL-6 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or a PGE2 monoclonal EIA kit (catalog no. 514010; Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples and standards were assayed in parallel. All assays were performed on triplicate plates, and the data are presented as the means±SEM.

Western blot analysis

The cells were harvested and lysed in buffer A (0.5% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], and protease inhibitors). Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), and 20-µg aliquots of total protein were electrophoresed in 8% or 10% polyacrylamide gels to detect COX-2 or PPARγ, respectively. The electrophoresed proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes by semi-dry electrophoretic transfer at 15 V for 60~75 min. The PVDF membranes were blocked overnight at 4℃ in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), incubated with primary antibody diluted at 1:500 in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% BSA for 2 h, and then incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody. The immunoreactive proteins were detected by ECL (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Scanning densitometry was performed using an Image Master® VDS (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA).

Transfection

Transient transfections with NF-κB-luciferase constructs were performed as described by Kim et al. (2006) using Lipofectin (Gibco-BRL). Briefly, 5×105 cells were plated on 60-mm plates the day before transfection and were grown to ~70% confluence. The cells were transfected with empty vector (pGL3 and/or pcDNA3), or 2 µg of the NF-κB-luciferase construct +0.5 µg of pRL-TK-luciferase. After 24 h, the transfected cells were washed with 4 ml of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and then treated as described below. Luciferase activity was normalized using pRL-TK-luciferase activity (Renilla luciferase activity) for each sample.

Luciferase assay

After the experimental treatments, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, lysed in a lysis buffer provided in the dual luciferase kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and assayed for luciferase activity using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All transfections were performed in triplicate. The data are presented as the ratio between firefly and Renilla luciferase activities.

Statistical analysis

Treatment groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the post-hoc test by Scheffe. The data are presented as the mean±SEM. p values <0.05 were accepted as significant unless otherwise indicated (*,†p<0.05, **,††p<0.01).

RESULTS

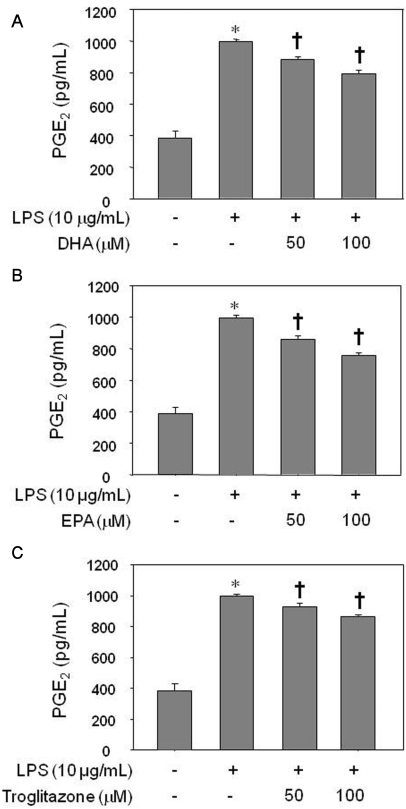

Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on PGE2 production in LPS-stimulated HUVECs

Treatment of HUVEC with LPS for 8 h significantly increased the PGE2 level as assessed by ELISA (p<0.05). Pretreatment of the cells with 50 µM or 100 µM of EPA, DHA, or troglitazone for 24 h decreased the LPS-induced augmentation in PGE2, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1; p<0.05). There was no significant difference among cell groups treated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inhibitory effect of DHA (A), EPA (B), or troglitazone (C) on PGE2 production by LPS-treated HUVECs. The results were confirmed by three experiments (n=6). Significance compared with the control, *p<0.05; significance compared with LPS, †p<0.05.

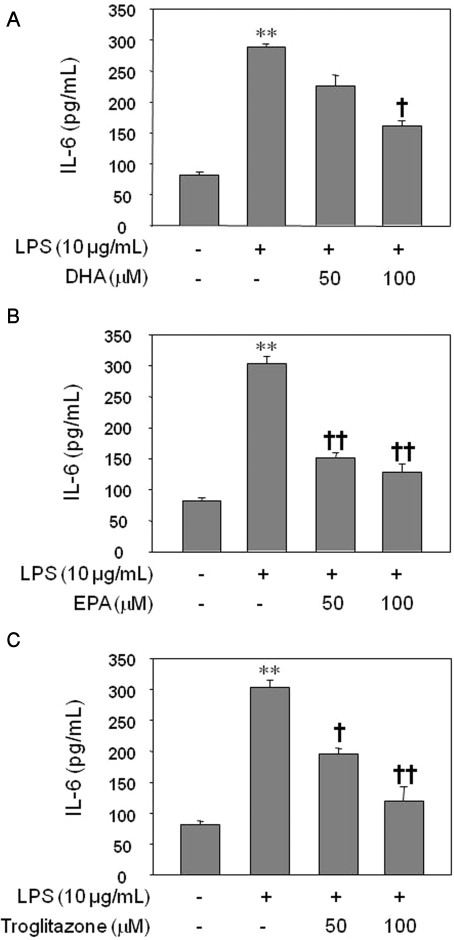

Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated HUVECs

Treatment of HUVECs with LPS for 8 h significantly increased the IL-6 level as assessed by ELISA (p<0.01). LPS-induced IL-6 production was decreased significantly by the pretreatment of the cells with 100 µM of DHA for 24 h (Fig. 2A; p<0.05) and by pretreatment with 50 and 100 µM of EPA for 24 h (Fig. 2B; p<0.01). Similarly, troglitazone pretreatment decreased IL-6 production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C; p<0.05, p<0.01). There was no significant difference in IL-6 production among cell groups treated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effect of DHA (A), EPA (B), or troglitazone (C) on IL-6 production by LPS-treated HUVECs. The results were confirmed by three experiments (n=6). Significance compared with the control, **p<0.01; significance compared with LPS, †p<0.05, ††p<0.01.

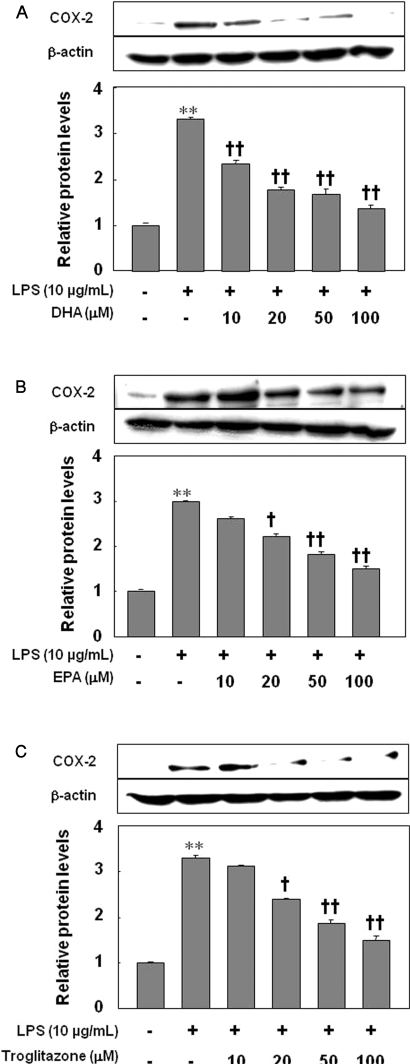

Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on COX-2 expression in LPS-stimulated HUVECs

Treatment of HUVECs with LPS for 8 h increased COX-2 expression as detected by immunoblotting (p<0.01). Pretreatment of HUVECs for 24 h with 10, 20, 50, and 100 µM of DHA significantly decreased the induction of COX-2 in LPS-treated HUVECs (Fig. 3A; p<0.01). Similarly, pretreatment of HUVECs with 20, 50, and 100 µM of EPA or troglitazone reduced COX-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B, C; p<0.05, p<0.01). There was no significant difference in COX-2 expression among cell groups treated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of DHA (A), EPA (B), or troglitazone (C) on the expression of COX-2. The results were confirmed by three experiments (n=3). Significance compared with the control, **p<0.01; significance compared with LPS, †p<0.05, ††p<0.01.

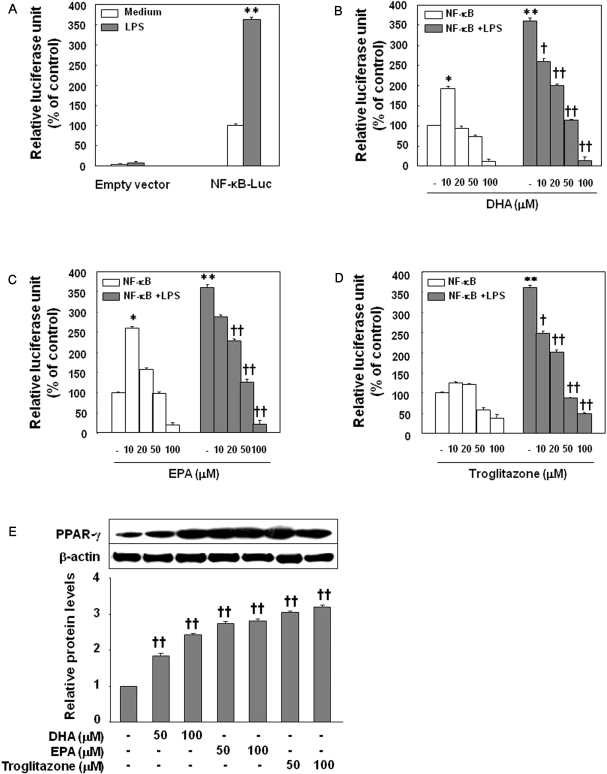

Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on NF-κB activity in LPS-stimulated HUVECs

In the luciferase assays performed after transfecting HUVECs with NF-κB vectors transiently, NF-κB luciferase activity increased in the LPS-treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 4A; p<0.01). Pretreatment of the cells for 24 h with 20, 50, and 100 µM EPA, DHA, or troglitazone significantly decreased LPS-induced luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B~D; p<0.01). There was no significant difference in NF-κB luciferase activity among the cell groups treated with DHA, EPA, or troglitazone (data not shown). While higher concentrations (100 µM) of DHA, EPA, and troglitazone reduced NF-κB luciferase activity in HUVECs with no LPS slightly (Fig. 4B~D), the lowest concentrations (10 µM) of EPA and DHA, but not troglitazone, increased NF-κB luciferase activity significantly (Fig. 4, p<0.05).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of LPS-induced NF-κB-luciferase activity by DHA, EPA, or troglitazone. Cells were transfected with 2 µg of NF-κB-luciferase, allowed to recover for 24 h, and then stimulated with LPS in the absence of agents (A) or in the presence of DHA (B), EPA (C), or troglitazone (D). Cells were harvested 8 h after treatment, and luciferase activities were determined. The results were confirmed by three experiments (n=6). Significance compared with NF-κB transfected control, *p<0.05, **p<0.01; significance compared with NF-κB+LPS, †p<0.05, ††p<0.01. (E) Effect of DHA, EPA, or troglitazone on PPARγ expression by HUVECs. The results were confirmed by three experiments (n=6). Significance compared with the control, ††p<0.01.

PPARγ expression by omega-3 fatty acids and troglitazone

Treatment of HUVECs with EPA, DHA or troglitazone for 24 h significantly increased the expression of PPARγ as detected by immunoblotting (p<0.01) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E, troglitazone>EPA>DHA).

DISCUSSION

It has become evident that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease with immune responses during initiation and progression of the disease. The presence of inflammatory cells can be observed in all stages of atherosclerosis, and activated inflammatory cells have been suggested to induce atherosclerotic plaque formation and destabilization (Ross, 1999; Libby, 2002). Our study showed that DHA and EPA clearly reduced the expression of COX-2 in HUVECs activated with LPS in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, pretreatment with DHA and EPA on LPS-treated HUVECs showed slight inhibition of PGE2 formation and more profound inhibition of IL-6 secretion. PGE2 and other 2-series PGs (i.e., PGD2, PGI2, PGE2, thromboxane A2, and PGF2α) are produced by COX from free arachidonic acid in inflammatory cells. With DHA or EPA supplementation, 3-series PGs (i.e., PGD3, PGI3, PGE3, and thromboxane A3), which are weaker inflammatory eicosanoids than 2-series PGs, are produced by COX (Serhan et al., 2000). Even though we did not test another inflammatory mediator enzyme, lipoxygenase (LOX), it is known that the potent inflammatory leukotrienes (LTB4 and LTE4) are produced by LOX, but n-3 PUFA substrates change them to weaker inflammatory leukotrienes (15-HEPE, ETE5, and ETB5; Philip CC., 2006). Recent studies have identified a novel group of mediators which exert anti-inflammatory actions, termed E-series resolvins (formed from EPA by COX-2), and D-series resolvins (docosatrienes and neuroprotectins from DHA) also produced by COX-2 (Serhan et al., 2002).

We hypothesized that PGE2 reduction and COX-2 suppression are indicative of the anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective actions of DHA and EPA. COX-2 suppression in our study was profound by DHA, EPA, and troglitazone in a dose-dependent manner. PGE2 and IL-6 production were also reduced. However, the conclusion that DHA and EPA have anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular protective effects is not so simple that they can be fully explained in terms of PGE2 reduction and COX-2 suppression. Even though PGE2 production was decreased, there was more profound COX-2 suppression. PGE2 mainly acts as a pro-inflammatory eicosanoid, but PGE2 also known to act as anti-inflammatory eicosanoid which inhibits the production of TNF and IL-1 (Philip, 2006). Furthermore, COX-2 suppression may involve the reduction of PGD2 (Scher and Pillinger, 2009), which is an anti-inflammatory eicosanoid, and PGI2, a vasodilator which has protective action in the human vascular system. Therefore, it is necessary to be aware that there may be some unknown long-term negative effects in vivo with COX-2 suppression by DHA and EPA.

DHA, EPA, or troglitazone supplementation did reduce IL-6 production. IL-6 is a well-known pro-inflammatory cytokine which can be liberated by inflammatory cells when stimulated by some pro-inflammatory eicosanoids (PGE2 and LTB4); this result was evidence of the anti-inflammatory effects of DHA and EPA. Thus, the overall physiologic or pathophysiologic outcome will depend on the cells present, the nature of the stimulus, the timing of eicosanoid generation, the concentrations of the different eicosanoids generated, and the sensitivity of the target cells and tissues to the eicosanoids generated (Philip, 2006).

Many inflammatory genes, including COX-2, and adhesion molecules are known to be under the control of nuclear transcription factor (NF-κB; Hayden and Ghosh, 2004; Goua et al., 2008; Massaro et al., 2008). Therefore, we addressed whether NF-κB activity, a common denominator of inflammatory stimulants, is involved in the inhibitory mechanism of DHA and EPA on COX-2 expression. As expected, these two chemicals significantly inhibited NF-κB luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner. This study suggests that omega-3 fatty acids attenuate the inflammatory reaction by inhibition of NF-κB in the vascular endothelium irrespective of the kinds of inflammatory stimulants, including LPS (Goua et al., 2008). Furthermore, the inhibition potency of DHA and EPA was similar to that of troglitazone, an anti-diabetic and synthetic PPARγ ligand (Rosen and Spiegelman, 2001; Blaschke et al., 2006). This suggests that the anti-inflammatory effect may be through the activation of PPARγ, which leads to inhibition of NF-κB activity (Delerive et al., 2001). Indeed, DHA and EPA increased PPARγ expression dose-dependently. This further supports the above notion that DHA and EPA act as PPARγ ligands (Massaro et al., 2008). Of course, there may be some relationships with other transcription factors, including AP-1, Sp1, GATA, and NFAT, although we did not evaluate such relationships (Delerive et al., 2001; Umetani et al., 2001).

It is of particular interest to note the results of NF-κB luciferase activity with DHA and EPA at the lowest dose (10 µM) in the absence of LPS. Both DHA and EPA significantly increase NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity (Fig. 4B, C, p<0.05, p<0.01) at such a dose, but troglitazone did not. This finding might provide a novel insight into the mechanisms of action of the DHA and EPA on NF-κB activity by their concentrations, even in the absence of inflammation in human vascular endothelium. Because we used commercially endotoxin-free materials under aseptic conditions, it is very unlikely that this novel result might come from endotoxin contamination of materials. To confirm this, however, it would be helpful to do further experiments with DHA, EPA, and troglitazone in concentrations <10 µM (e. g., 1 or 5 µM). Thus, an abnormally lower concentration of n-3 fatty acids may cause injury in the endothelial cell, which worsens the intact endothelium or pre-existing endothelial damage by activating NF-κB transcription factor. More attention should be focuses on how concentrations of these fatty acids really affect human health, in particular the cardiovascular system.

This study supported the previous reports that n-3 fatty acids attenuate inflammation in endothelial cells induced by inflammatory stimulants, such as cytokines (Massaro et al., 2006; Goua et al., 2008; Massaro et al., 2008). However, in our study, inflammation was induced by the administration of LPS to the human endothelial cells, not by some cytokines as many other studies did. LPS was suggested as one of the important causative agents of atherosclerosis (Triantafilou et al., 2007). Recently, chlamydial LPS (cLPS) in plaques in human atherosclerotic and aneurysmal arterial walls was suggested to produce an innate immune response reaction and its concentration was related to that of serum markers (IL-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein CRP; Vikatmaa et al., 2009). Although clinically, its contribution in inducing atherosclerosis may be low, it may be meaningful for patients who are infected with pathogens and pre-existing cardiovascular diseases.

In conclusion, we speculate that keeping inadequately low blood concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids throughout life might have a disadvantageous effect on the vascular endothelium in forming atherosclerosis, even without other risk factors. It is necessary to evaluate the mechanisms of how low concentrations of DHA and EPA increase NF-κB activity in the absence of inflammatory stimuli.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Special Clinical Fund of Gyeongsang National University Hospital in 2007.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- ECGS

endothelial cell growth supplements

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

References

- 1.Abeywardena MY, Head RJ. Long chain n-3 polyunsaturatedfatty acids and blood vessel function. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagga D, Wang L, Farias-Eisner R, Glaspy JA, Reddy ST. Differential effects of prostaglandin derived from omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on COX-2 expression and IL-6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1751–1756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334211100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaschke F, Spanheimer R, Khan M, Law RE. Vascular effects of TZDs: New implications. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;45:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cipollone F, Fazia ML. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition: vascular inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006;8:245–251. doi: 10.1007/s11883-006-0080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delerive P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in inflammation control. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:453–459. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engler MB, Engler MM, Browne A, Sun YP, Sievers R. Mechanisms of vasorelaxation induced by eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) in WKY rat aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1793–1799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goua M, Mulgrew S, Frank J, Rees D, Sneddon AA, Wahle KW. Regulation of adhesion molecule expression in human endothelial and smooth muscle cells by omega-3 fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acids: involvement of the transcription factor NF-kappaB? Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;78:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazemi MR, McDonald CM, Shigenaga JK, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein expression and lipid accumulation are increased during activation of murine macrophages by toll-like receptor agonists. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1220–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000159163.52632.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HJ, Tsoy I, Park JM, Chung JI, Shin SC, Chang KC. Anthocyanins from soybean seed coat inhibit the expression of TNF-alpha-induced genes associated with ischemia/reperfusion in endothelial cell by NF-kappaB-dependent pathway and reduce rat myocardial damages incurred by ischemia and reperfusion in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1391–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libby CP. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massaro M, Habib A, Lubrano L, Del Turco S, Lazzerini G, Bourcier T, Weksler BB, De Caterina R. The omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoate attenuates endothelial cyclooxygenase-2 induction through both NADP (H) oxidase and PKC epsilon inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15184–15189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510086103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massaro M, Scoditti E, Carluccio MA, De Caterina R. Basic mechanisms behind the effects of n-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular disease. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Philip CC. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(Suppl):1505S–1519S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. PPARγ: a nuclear regulator of metabolism, differentiation, and cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37731–37734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross R. Atherosclerosis - an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scher JU, Pillinger MH. J Investig Med. 2009. Feb 20, The anti-inflammatory effects of prostaglandins. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serhan CN, Clish CB, Brannon J, Colgan SP, Chiang N, Gronert K. Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1197–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, Colgan SP, Devchand PR, Mirick G, Moussignac RL. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter pro-inflammation signals. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1025–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S, Guyton JR, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schaffer SA, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the committee on vascular lesions of the council on arteriosclerosis, American heart association. Circulation. 1994;89:2462–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoll LL, Denning GM, Weintraub NL. Potential role of endotoxin as a proinflammatory mediator of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2227–2236. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147534.69062.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triantafilou M, Gamper FG, Lepper PM, Mouratis MA, Schumann C, Harokopakis E, Schifferle RE, Hajishengallis G, Triantafilou K. Lipopolysaccharides from atherosclerosis-associated bacteria antagonize TLR4, induce formation of TLR2/1/CD36 complexes in lipid rafts and trigger TLR2-induced inflammatory responsesin human vascular endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2030–2039. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umetani M, Mataki C, Minegishi N, Yamamoto M, Hamakubo T, Kodama T. Function of GATA transcription factors in induction of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 by tumornecrosis factor-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:917–922. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vikatmaa P, Lajunen T, Ikonen TS, Pussinen PJ, Lepäntalo M, Leinonen M, Saikku P. Chlamydial lipopolysaccharide (cLPS) is present in atherosclerotic and aneurysmal arterial wall-cLPS levels depend on disease manifestation. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2009 Jan 14; doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.10.012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]