Abstract

Galectins, a family of ß-galactoside-binding proteins, participate in a variety of biological processes, such as early development, tissue organization, immune regulation, and tumor evasion and metastasis. Although as many as fifteen bona fide galectins have been identified in mammals, but the detailed mechanisms of their biological roles still remain unclear for most. This fragmentary knowledge extends to galectin-like proteins such as the rat lens crystallin protein GRIFIN (Galectin related inter fiber protein) and the galectin-related protein GRP (previously HSPC159; hematopoietic stem cell precursor) that lack carbohydrate-binding activity. Their inclusion in the galectin family has been debated, as they are considered products of evolutionary co-option. We have identified a homologue of the GRIFIN in zebrafish (Danio rerio) (designated DrGRIFIN), which like the mammalian equivalent is expressed in the lens, particularly in the fiber cells, as revealed by whole mount in situ hybridization and immunostaining of 2 dpf (days post fertilization) embryos. As evidenced by RT-PCR, it is weakly expressed in the embryos as early as 21 hpf (hour post fertilization) but strongly at all later stages tested (30 hpf and 3, 4, 6, and 7 dpf). In adult zebrafish tissues, however, DrGRIFIN is also expressed in oocyte, brain, and intestine. Unlike the mammalian homologue, DrGRIFIN contains all amino acids critical for binding to carbohydrate ligands and its activity was confirmed as the recombinant DrGRIFIN could be purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography on a lactosyl-Sepharose column. Therefore, DrGRIFIN is a bona fide galectin family member that in addition to its carbohydrate-binding properties, may also function as a crystallin.

Keywords: galectin, GRIFIN, zebrafish, Danio rerio, carbohydrate recognition domain, lens crystallin

Complex carbohydrate structures modulate interactions between cells or between cells and the extracellular matrix by specifically binding to cell surface–associated or soluble carbohydrate-binding receptors [1]. Among these, galectins, formerly known as S-type lectins, are ß-galactoside-binding proteins that have been proposed to participate in a variety of biological processes, such as early development, tissue organization, immune functions, host-parasite interactions, tumor evasion and cancer metastasis [2-7]. However, the detailed mechanisms of their biological roles still remain unclear. Based on structural features, galectins have been classified in three types: proto, chimera, and tandem-repeat [8]. Prototype galectins contain one carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRD) per subunit and are usually homodimers of noncovalently linked subunits. In contrast, chimera-type galectins are monomeric with a C-terminal CRD similar to the proto type, joined to an N-terminal peptide containing a collagen-like sequence rich in proline and glycine. Tandem-repeat galectins, in which two CRDs are joined by a linker peptide, are also monomeric. Proto- and tandem-repeat types make up several distinct galectin subtypes. Galectin subtypes have been numbered following the order of their discovery [9], and so far, 15 have been described in mammals [10]. Gal1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, and 15 are examples of the proto type galectins- of which gal5 is monomer, whereas all others are homodimers. Gal3 is the only chimera type galectin; whereas Gal4, 6, 8, 9, and 12 are examples of the tandem-repeat type galectins.

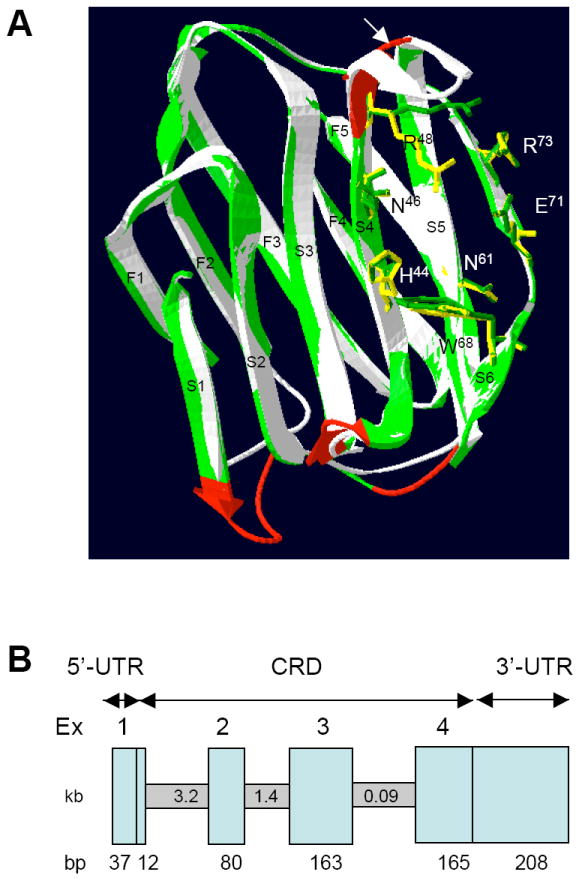

The structures of proto-type galectins have been resolved during the past few years revealing a common jellyroll topology, typical of legume lectins [11, 12]. In the galectin dimer, each subunit is composed of an 11-strand antiparallel ß-sandwich that contains a CRD, with the N- and C-termini located at the dimer interface. The structure of the bovine (Bos taurus) gal1-LacNAc (N-acetyllactosamine) complex revealed that the amino acids H44, N46, R48, N61, E71, and R73 are directly involved in hydrogen bonding with the 4 and 6 hydroxyls of the galactose unit, and the 3 hydroxyl of the N-acetylglucosamine group of the LacNAc. W69 provides a strong hydrophobic interaction with the galactose ring of the LacNAc [11]. Thus, the structure of the galectin-ligand complex has provided provides a detailed description of the lectin-carbohydrate-interactions.

In the past decade, several galectin-like proteins such as the lens crystallin protein GRIFIN (Galectin related inter-fiber protein) and the galectin-related protein GRP (previously HSPC159; hematopoietic stem cell precursor) have been identified [10,13, 14]. Although they have close similarity to galectin sequences, due to the lack of carbohydrate-binding activity they are not considered to be members of the galectin family, but putative products of evolutionary co-option. GRIFIN, described in the rat as a novel crystallin [13], is expressed at the interface between lens fiber cells, and was proposed to have evolved from a galectin precursor that has lost its capacity to bind lactose. Crystallins are water-soluble structural proteins that account for the transparency of the vertebrate lens. They constitute a heterogeneous family of composed of four major groups (α–δ) and several minor groups, with roles as both molecular chaperones and structural proteins [15].

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) has been established as a useful animal model for studies of early development because this species offers a number of advantages over mammalian systems such as external fertilization, rapid development of embryo, transparent embryo, easy genetic manipulation, and an extensive collection of mutants. Thus, we proposed that it may also constitute the model of choice for gaining further insight into the biological roles of galectins [4]. Recently, we characterized the zebrafish galectin repertoire as follows: three gal1-like proteins (Drgal1-L1, Drgal1-L2, Drgal1-L3), one chimera type galectin (Drgal3), and two gal9-like proteins (Drgal9-L1 and Drgal9-L2) [16]. In silico analysis of the nearly completed genome sequence has enabled the identification of additional members, such as gal4-, gal5-, and gal8-like proteins (NIH Zebrafish Genome Project).

In this study we identified a GRIFIN homologue in zebrafish (designated DrGRIFIN), which is expressed in the lens, particularly in the fiber cells, of early embryos. Unlike the mammalian GRIFIN, however, DrGRIFIN is also expressed in oocyte, brain, and intestine in the adult zebrafish tissues. Surprisingly, in contrast with the mammalian homologue, DrGRIFIN contains all amino acids critical for binding to carbohydrate ligands and its activity was confirmed as the recombinant DrGRIFIN could be purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography on a lactosyl-Sepharose column.

Materials and methods

Database search and sequence analyses

The Danio rerio genome database was searched for galectin sequences through the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) web page (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). TBLASTN program in the NCBI web page was then used to search the translated nucleotide database using a protein query [17]. Amino acid sequences were aligned by ClustalW program.

Homology modeling

Homology modeling of DrGRIFIN based on the bovine gal1 structure [11] was performed using SWISS-MODEL [Version 3.7] [18] at the SWISS-MODEL Protein Modeling Server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org)].

Analytical procedures

Protein concentration measurements and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS-PAGE) were carried as described elsewhere [19]. For immunoblotting, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred, and probed with a mouse anti-rat GRIFIN monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) as reported earlier [19].

Maintenance of zebrafish and collection of embryos

Zebrafish were raised according to the standard method previously described [20]. At the onset of light, a female and a male fish were placed in an egg collection tank at 28.5 °C, and the embryos sampled at various developmental stages.

Analyses of temporal and spatial expression of DrGRIFIN by reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from several embryonic stages and adult organs of zebrafish as previously described [16]. Poly (A)+ RNA was purified from the total RNA on poly (dT)-Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For RT-PCR analysis, first strand cDNAs were generated from the purified mRNA using the cDNA synthesis kit (Life Technologies), and used as template for PCR amplification. All PCR amplifications were carried out with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) in the buffer and Mg2+ solution provided by the manufacturer. Annealing temperatures varied from 50 to 65 °C. The non-overlapping DrGRIFIN specific primers used were as follows: DrGRIFINF1 (5’-CGGTTTGAGGCTTCCTGTCC-3’) and DrGRIFINR1 (5’-GCATCACTTTGGCTTTGTCG-3’).

Cloning and sequencing

The DrGRIFIN amplicon obtained by PCR was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Plasmids for DNA sequencing were prepared using the QIAprep Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or GenElute Five-Minute Plasmid Miniprep kit (Sigma). DNA sequences were determined by the dye termination cycle sequencing method using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI 3130 XL instrument equipped with 16 capillary columns (50 cm length) (Applied Biosystems) by using the vector primers (Novagen, Madison, WI). All other manipulations of nucleic acids such as ligation, transformation, gel electrophoresis, gel elution, and preparation of buffers were carried out following standard protocols [21].

Expression and purification of recombinant DrGRIFIN

To construct a DrGRIFIN expression plasmid the complete open reading frame was inserted between the NdeI and EcoRIrestriction sites of the pET-30 expression vector (Novagen). The following primers DrGRIFINNdeI: 5’-CCGGCCAATTCCATATGACATTACGGTTT-GAGGC-3’ and DrGRIFINEcoRI: 5’-CGGAATTCCGCCGCCCAGACTCAGT-3’ were used to amplify zebrafish eye cDNA to generate a PCR product that includes an artificial NdeI site coinciding with the start codon, ATG, and a EcoRI site at the stop codon. After cloning the product into the pGEM-T vector (Promega), the DrGRIFIN insert was released and cloned into the pET30. For expression and isolation of the recombinant DrGRIFIN protein (recDrGRIFIN), E.coli strain BL21 (DE3) competent cells were transformed with the DrGRIFIN-pET30 construct and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-ß-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min) and disrupted by lysozyme treatment (100 μg/ml) for 15 min at 30 °C, followed by sonication in PBS supplemented with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (ME/PBS) and 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The soluble fraction was cleared by centrifugation (14,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min) and directly applied to a lactose-Sepharose affinity column equilibrated in ME/PBS. The column was extensively washed in ME/PBS and the bound recDrGRIFIN was eluted with 5 bed volumes of 100 mM glucose in ME/PBS followed by 5 bed volumes of 100 mM lactose in ME/PBS. The purification of recDrGRIFIN was monitored by estimating protein content at each step.

Whole mount in situ hybridization and immunostaining

In situ hybridization and immunostaining were carried out following the protocols previously described [16].

Results and discussion

Zebrafish expresses a homologue of the mammalian GRIFIN

Through in silico analysis we identified a proto type galectin sequence (GenBank accession no. NM001003430) that in BLAST analysis produced the highest match with the mammalian GRIFIN. We named this protein DrGRIFIN (see Fig. 4 from the Supplementary Materials). When compared with mammalian and bird GRIFINs, the amino acid sequence identity of DrGRIFIN ranges from 32.3% (human) to 52.5% (chicken) (see Fig. 5 from the Supplementary Materials), with about thirty invariant amino acid residues in all GRIFIN sequences. Among the galectin sequences we identified in zebrafish (at least four proto type, one chimera, and at least four tandem-repeat) [16], the highest % identity with DrGRIFIN was observed with the chimera galectin (Drgal3) (see Fig. 6 from the Supplementary Materials). Close examination of the DrGRIFIN sequence corresponding to the carbohydrate-binding site revealed that it contains all seven amino acids (H44, N46, R48, N61, W68, E71, R73; numbering based on bovine galectin-1 sequence, shown shaded in Fig. 5 from the Supplementary Materials) that are responsible for the carbohydrate binding activity, as demonstrated from the 3-D structure of the gal1-LacNAc complex [11]. Thus, the primary structure of DrGRIFIN strongly suggested that it binds carbohydrates. This is in contrast to all other GRIFINs described so far, which at most exhibit only five of those amino acids as follows: H44, R48, N61, W68, and E71, except for the chicken GRIFIN that contains H44, N46, R48, N61, and W68, and are considered to lack sugar binding activity.

The DrGRIFIN CRD is structurally similar to the mammalian galectin CRD

To investigate further whether DrGRIFIN could bind carbohydrate ligands, we modeled DrGRIFIN on the basis the bovine gal1 structure. Despite the relatively low amino acid identity (23 %), the homology model revealed a striking structural similarity between DrGRIFIN and the mammalian galectin CRD (Fig. 1A). Except for moderate differences in the loops between the β-strands S1 and F2 and between strands S4 and S5, all eleven strands of DrGRIFIN (shown in green) are well aligned with those of the bovine gal1 (shown in white). Moreover, except for R48 (numbering based on the bovine gal1 sequence) all the essential carbohydrate-binding amino acids (shown in green) in DrGRIFIN are closely aligned with those (shown in yellow) from the bovine gal1, and thus, should be capable of binding carbohydrates such as lactose. However, because the loop between the β strands S4 and S5 in DrGRIFIN (Fig. 1A, shown by arrow) is shorter, the carbohydrate-binding specificity of DrGRIFIN may show some differences to that of the bovine gal1. Due to this short loop in DrGRIFIN, R48 is pointing away from the binding pocket and may not be accessible for interactions with the carbohydrate ligands. In the 16 kDa galectin from Caenorhabditis elegans [22], a similar shorter loop between the β strands 4 and 5 results in unique binding activities for blood group precursor oligosaccharides (Tα, Galβ1,3GalNAcα; Tβ, Galβ1,3GalNAcβ; type 1, Galβ1,3GlcNAc; type 2, Galβ1,4GlcNAc) [22]. However, because the crystal structure of galectin-3 (C-CRD) reveals that R29 in β-strand 3 makes a direct hydrogen bond interaction with the bound oligosaccharide [23], additional interactions of DrGRIFIN with the carbohydrate ligands that may be mediated by amino acids other than those in β-strands 4 and 5 cannot be ruled out.

Fig. 1.

(A) Homology modeling of DrGRIFIN. Ribbon diagram showing the overlap of the DrGRIFIN (green) and the bovine gal1 structure (white, PDB code 1SLT, ref. 9). The amino acids that are essential for carbohydrate-binding are shown in green for DrGRIFIN, and yellow for bovine gal1.

(B) Genomic organization of DrGRIFIN. The vertical boxes represent exons, which are numbered at the top. The size of each exon (in bp) is indicated at the bottom. The horizontal boxes represent introns, whose sizes are indicated in kb in the middle.

The DrGRIFIN gene structure is similar to that of the mammalian gal1 genes

A sequence homology search (TBLASTN) of DrGRIFIN in the zebrafish genome, identified a 5,324 bp gene, composed of 4 exons [Exon 1, 12 bp; 2, 80 bp; 3, 163 bp; and 4, 165 bp (lengths are without 5’ and 3’ UTR)] (Fig. 1B). The gene is located in chromosome 3 spanning between 2602.067 kb to 2596.744 kb. Despite some differences in intron sizes, the organization of the DrGRIFIN gene (exon/intron boundaries and number of exons) is similar to the mammalian and avian gal1 genes [8]. The organization of gal1 genes from human, mouse, chicken and zebrafish is remarkably similar in exon number and length, [16, 24-27]: exon 1, 6-9 bp; exon 2, 80-83 bp; exon 3, 160-172 bp; exon 4, 144-150 bp, of which the largest (exon 3) encodes the carbohydrate binding site. It is noteworthy that the rat GRIFIN gene is smaller (about 2 kb) than the DrGRIFIN gene, but it contains five exons: exon 1, 12 bp; exon 2, 80 bp; exon 3, 160 bp; exon 4, 167 bp; exon 5, 16 bp [13]. The mouse GRIFIN is similar to the rat GRIFIN in both length and organization (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

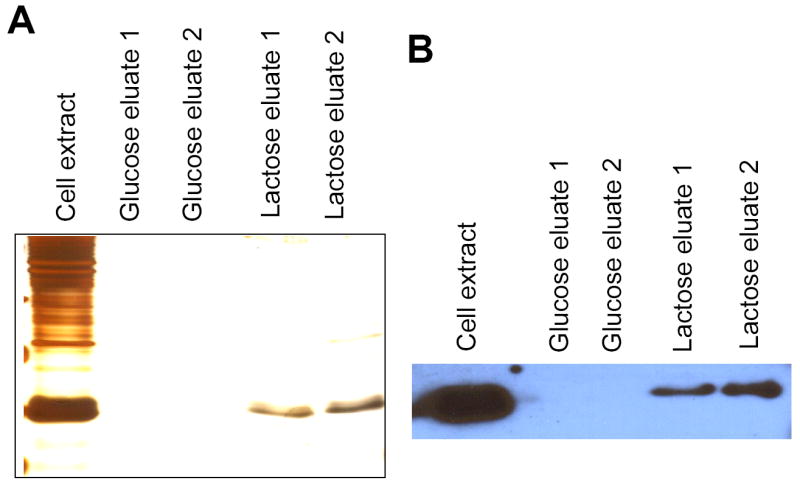

Unlike mammalian GRIFIN, DrGRIFIN represents a functional carbohydrate-binding galectin

Transformation of BL21(DE3) cells with the DrGRIFIN-pET 30 and then IPTG-induction resulted abundant expression of recDrGRIFIN as evidenced by SDS-PAGE (not shown). The recDrGRIFIN was obtained mostly in the soluble fraction of the cell extract, and bound strongly to the lactosyl-Sepharose column, as the column washthrough did not show any DrGRIFIN on SDS-PAGE (not shown). Like other galectins, the binding of DrGRIFIN was specific for lactose, as the bound protein was eluted as a single band with lactose, but not with glucose (Fig. 2A). The strong cross-reactivity of DrGRIFIN with an anti-rat GRIFIN monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2B) provided further evidence of its structural similarity to rat GRIFIN.

Fig. 2.

(A) Purification of recombinant DrGRIFIN on a lactosyl-Sepharose. The extract was absorbed on lactosyl-Sepahrose, and the bound protein was eluted with 0.1 M glucose followed by 0.1 M lactose. Samples of each step were electrophoresed and silver-stained.

(B). Serological cross-reactivity of anti-rat GRIFIN antibody with DrGRIFIN.

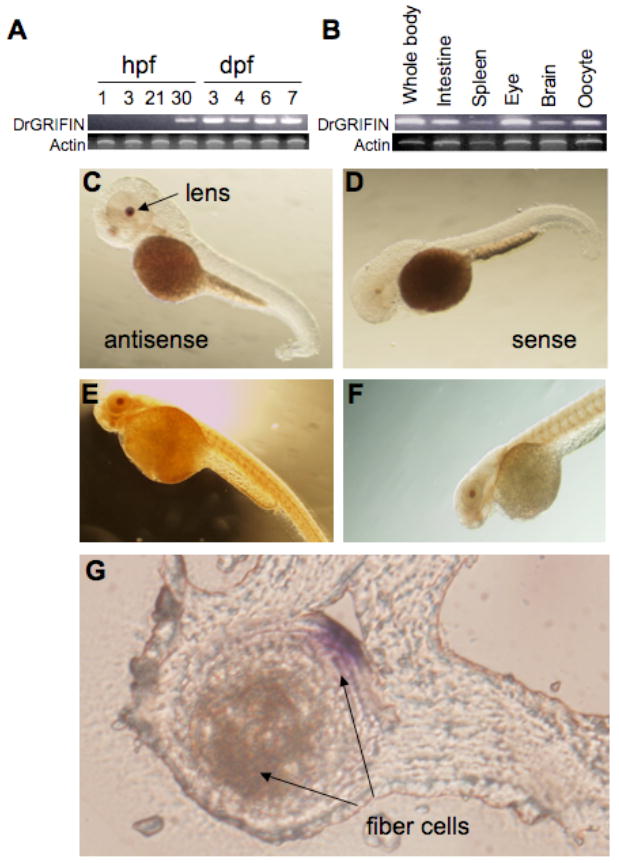

In early embryos DrGRIFIN is exclusively localized in the eye lens

Analysis of the temporal expression of DrGRIFIN by RT-PCR in zebrafish embryos revealed a faint band as early as 21 hpf, the earliest stage of eye development, with higher expression levels at all later stages tested (Fig. 3A). In the adult zebrafish, the strongest expression was observed in the eye, followed by oocyte, intestine, and brain (Figure 3B). Whole mount in situ hybridization in 48 hpf embryos indicated that DrGRIFIN is exclusively expressed in the eye lens (Fig. 3C; 3D). This observation was corroborated by whole mount immunostaining of 48 hpf embryos with an anti-rat GRIFIN monoclonal antibody, that only stained the lens (Fig. 3E; 3F). Microscopic examination of thin sections (10 micron) from eyes from zebrafish that had been tested by in situ hybridization revealed that like rat GRIFIN, DrGRIFIN is highly expressed in the lens fiber cells (Fig. 3G). Although the spatial expression of DrGRIFIN in early embryos is restricted to the lens, in adult zebrafish its expression is not only confined to the eye, but also other organs such as oocytes, intestine, and brain. This observation is in sharp contrast to the expression of rat GRIFIN, whose expression in adult animals is restricted to the lens [13]. The rat GRIFIN is localized at the interface between lens fiber cells and is believed to function as a crystallin [13], and a similar localization of DrGRIFIN suggests that it may have a similar function. However, expression of DrGRIFIN in tissues other than the lens of adult zebrafish, such oocytes, intestine, and brain suggests that in addition to contributing to the physical/functional properties of the lens, it may have additional biological roles most likely related to its carbohydrate binding properties.

Fig. 3.

Expression of DrGRIFIN in zebrafish identified by RT-PCR. (A) Temporal expression patterns; (B) Spatial expression patterns (tissue/organ-specific) in the adult C-G. Whole mount in situ hybridization and immunostaining. (C, D) In situ hybridization of whole zebrafish embryo (2 days post fertilization, dpf) showing (C) DrGRIFIN expression in lens (lateral view); (D) 2 dpf embryos (lateral view) with sense probe for negative control.

E, F. Whole mount immunostaining with anti-rat GRIFIN monoclonal antibody showing DrGRIFIN expression in lens. E and F are the same, but with different time of substrate development.

G. Cross-section of eye after whole mount in situ hybridization.

DrGRIFIN: an intermediate step in an evolutionary co-option process?

As discussed above, although the rat GRIFIN contains a galectin-like CRD sequence, it does not bind carbohydrate, and this is probably due to the lack of two of the seven essential amino acids in the carbohydrate-binding site [13]. The other mammalian and bird GRIFINs identified so far also lack two essential amino acids, and most likely lack carbohydrate-binding activity. Because the rat GRIFIN is an abundant soluble protein exclusively expressed in the lens fiber cells, it has been suggested that it functions as a crystallin [13]. Further, considering the close similarity of the mammalian and avian GRIFINs to gal3, it has been suggested that GRIFIN derives from gal3 in a process of evolutionary co-option but has lost its capacity to bind lactose when recruited to the lens as a crystalline [28]. Another example of possible co-option is the galectin-related protein GRP, which also exhibits a galectin-like sequence but lacks carbohydrate-binding activity [10, 14]. Because among all zebrafish galectins DrGRIFIN is also closest to Drgal3, it is tempting to speculate that like bidr and mammalian GRIFINs, DrGRIFIN has also evolved from Drgal3. However, because unlike the avian and mammalian homologues, DrGRIFIN still retains its carbohydrate-binding activity, and like its precursor Drgal3 it is expressed in various adult zebrafish tissues, DrGRIFIN would mediate functions related to the transparency of the lens, and like a bona fide galectin, mediate interactions between cells, and cells and the extracellular matrix either in the lens or other tissues. Thus, DrGRIFIN may represent an intermediate step in the co-option process that in vertebrate evolution has led from an active sugar-binding galectin to a non-sugar binding crystallin in the extant birds and mammals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Debasish Sinha (The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD) for advise on interpretation of eye sections. This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant RO1 GM070589-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bakkers J, Semino CE, Stroband H, Kijne JW, Robbins PW, Spaink HP. An important developmental role for oligosaccharides during early embryogenesis of cyprinid fish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:29–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirabayashi J, editor. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol. Vol. 9. 1997. Recent topics on galectins; pp. 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leffler H, Carlsson S, Hedlund M, Qian Y, Poirier F. Introduction to galectins. Glycoconj J. 2004;19:433–440. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000014072.34840.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasta GR, Ahmed H, Du S, Henrikson D. Galectins in teleost fish: Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model species to address their biological roles in development and innate immunity. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:503–521. doi: 10.1007/s10719-004-5541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu FT, Rabinovich GA. Galectins as modulators of tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:29–41. doi: 10.1038/nrc1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabinovich GA, Toscano MA, Jackson SS, Vasta GR. Functions of cell surface galectin-glycoprotein lattices. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tasumi S, Vasta GR. A novel galectin facilitates entry of the parasite Perkinsus marinus into oyster hemocytes. J Immunol. 2007;179:3086–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirabayashi J, Kasai K. The family of metazoan metal-independent β-galactoside-binding lectins: structure, function and molecular evolution. Glycobiology. 1993;3:297–304. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barondes SH, Cooper DNW, Gitt MA, Leffler H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20807–20810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper DNW. Galectinomics: a lesson in complexity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:209–231. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao DI, Kapadia G, Ahmed H, Vasta GR, Herzberg O. Structure of S-lectin, a developmentally regulated vertebrate β-galactoside-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:1428–1432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasta GR, Ahmed H, Odom EW. Structural and functional diversity of lectin repertoires in invertebrates, protochordates and ectothermic vertebrates. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogden AT, Nunes I, Ko K, Wu S, Hines CS, Wang AF, Hegde RS, Lang RA. GRIFIN, a novel lens-specific protein related to the galectin family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28889–28896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou D, Sun J, Zhao W, Zhang X, Shi Y, Teng M, Niu L, Dong Y, Liu P. Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray characterization of the GRP carbohydrate-recognition domain from Homo sapiens. Acta Crystallogr. 2006;62:474–476. doi: 10.1107/S1744309106012875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piatigorsky J. Lens crystallins and their genes: diversity and tissue-specific expression. FASEB J. 1989;3:1933–1940. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.8.2656357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed H, Du SJ, O’Leary N, Vasta GR. Biochemical and molecular characterization of galectins from zebrafish (Danio rerio): notochord-specific expression of a prototype galectin during early embryogenesis. Glycobiology. 2004;14:219–232. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed H, Pohl J, Fink NE, Strobel F, Vasta GR. The primary structure and carbohydrate specificity of a β-galactosyl-binding lectin from toad (Bufo arenarum Hensel) ovary reveal closer similarities to the mammalian galectin-1 than to the galectin from the clawed frog Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33083–33094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westerfield M. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) 4. The University of Oregon Press; Eugene, OR: 2004. The zebrafish book. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. A Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. Molecular Cloning. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed H, Bianchet MA, Amzel LM, Hirabayashi J, Kasai K, Giga-Hama Y, Tohda H, Vasta GR. Novel carbohydrate specificity of the 16 kDa galectin from Caenorhabditis elegans: binding to blood group precursor oligosaccharides (type 1, type 2, Tα, and Tβ) and gangliosides. Glycobiology. 2002;12:451–461. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seetharaman J, Kanisberg A, Slaaby R, Leffler H, Barondes SH, Rini JM. X-ray crystal structure of the human galectin-3 carbohydrate recognition domain at 2.1-A resolution. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13047–13052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohyama Y, Kasai K. Isolation and characterization of the chick 14K beta-galactoside-binding lectin gene. J Biochem. 1988;104:173–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiariotti L, Wells V, Bruni CB, Mallucci L. Structure and expression of the negative growth factor mouse β-galactoside binding protein gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1089:54–60. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gitt MA, Barondes SH. Genomic sequence and organization of two members of a human lectin gene family. Biochemistry. 1991;30:82–89. doi: 10.1021/bi00215a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gitt MA, Massa SM, Leffler H, Barondes SH. Isolation and expression of a gene encoding L-14-II, a new human soluble lactose-binding lectin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10601–10606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houzelstein D, Goncalves IR, Fadden AJ, Sidhu SS, Cooper DN, Drickamer K, Leffler H, Poirier F. Phylogenetic analysis of the vertebrate galectin family. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1177–1187. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.