Summary

Axonemes of motile eukaryotic cilia and flagella have a conserved structure of nine doublet microtubules surrounding a central pair of microtubules. Outer and inner dynein arms on the doublets mediate axoneme motility [1]. Outer dynein arms (ODAs) attach to the doublets at specific interfaces [2–5]. However, the molecular contacts of ODA-associated proteins with tubulins of the doublet microtubules to mediate ODA attachment are not known. We report here that attachment of ODAs requires glycine 56 in the β-tubulin internal variable region (IVR). We show that in Drosophila spermatogenesis, a single amino acid change at this position results in sperm axonemes markedly deficient in ODAs. We moreover found that axonemal β-tubulins throughout phylogeny have invariant glycine 56 and a strongly conserved IVR, whereas non-axonemal β-tubulins vary widely in IVR sequences. Our data reveal a deeply conserved physical requirement for assembly of the macromolecular architecture of the motile axoneme. Amino acid 56 projects into the microtubule lumen [6]. Imaging studies of axonemes indicate several proteins may interact with the doublet microtubule lumen [3, 4, 7, 8]. This region of β-tubulin may determine conformation necessary for correct attachment of ODAs, or there may be sequence-specific interaction between β-tubulin and a protein involved in ODA attachment or stabilization.

Results and Discussion

Axoneme bending, and thus flagellar beating, occurs when dynein arms move along the adjacent doublet [9]. Dynein-mediated motility requires ATP-dependent interactions of the dynein heavy chain motor domain with C-terminal regions of the β-tubulin component of theα,β-tubulin dimers of the B-tubule [7, 10–12]. At the other end, the ODAs are anchored to the doublet A-tubule via a suite of proteins associated with the base of the arm [2, 5, 7, 13–17]. Our discovery of a specific sequence requirement in axonemal β-tubulin for attachment of ODAs provides the first information about molecular interactions between tubulins of the A-tubule and proteins involved in attaching ODAs.

Distinct β-tubulin isotype classes with conserved expression patterns were identified in vertebrate β-tubulin families, based on sequences in two variable domains, the final C-terminal tail (CTT) and a smaller internal variable region (IVR) comprising amino acids 55–57 [18]. Other β-tubulin families are not homologous to the vertebrate families, but a role for the variable regions in functional specialization is conserved. Using Drosophila spermatogenesis as a model, we have identified specific β-tubulin CTT requirements for motile axonemes, including an axoneme motif shared by all axonemal β-tubulins [19–25]. The sequence requirement for ODAs we demonstrate here is the first identification of a distinct function for the IVR.

A single amino acid mediates outer dynein arm attachment in Drosophila sperm axonemes

We observed that ODAs are reliably present in most cross-sections of axonemes generated by all but two of many β-tubulins we examined for their ability to support axoneme assembly in Drosophila spermatogenesis (Table 1). ODAs were deficient in axonemes utilizing β-tubulins with variant IVRs, but even substantial changes in C-terminal sequences did not affect ODA attachment. The most elegant example is the B2t6 mutation in the Drosophila testis-specific β2-tubulin, which has a single change at amino acid 56 in the IVR (Table 1) [26]. B2t6 mutant males make intact but nonmotile sperm axonemes in which the majority of doublets lack ODAs (Table 2; Fig. 1). Attachment of inner dynein arms (IDAs) is unaffected. The B2t6 mutation is fully recessive. Heterozygous males incorporate equal amounts of wild type β2 and the B2t6 protein into sperm; axonemes have normal morphology and males are fully fertile [22, 26, 27]. Thus functional axoneme architecture can accommodate 50% of the B2t6 protein.

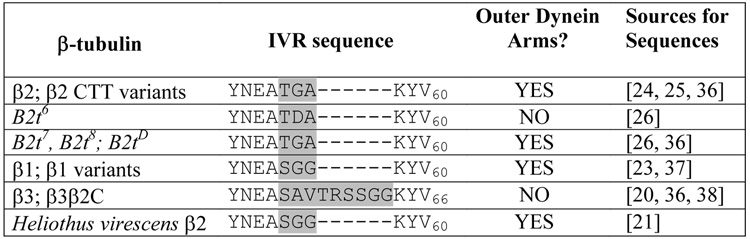

Table. 1. Sequences of the internal variable region in β-tubulins tested for axoneme assembly in Drosophila melanogaster spermatogenesis.

IVRs shaded: amino acids 55–57 in Drosophila β2, β1, and derivatives; 55–63 in β3 and β3β2C. The IVR is flanked by conserved sequences, as shown. B2t6 makes axonemes, but they are nonfunctional [26, 27]. ODAs are substantially deficient (Table 2, Fig. 1, online supplemental Table S1). Neither Drosophila β3 nor β3β2C (a chimera with β3 sequences joined to the β2 C-terminus [20]; Table S1) can alone support axoneme assembly, and rarely make doublets. In the few examples, ODAs are absent [20, 38]. Both of these proteins inhibit ODA addition when co-expressed with wild type β2 (Table 3, Fig. 2, Table S1). All other β-tubulins tested for axoneme assembly in Drosophila spermatogenesis consistently have ODAs, even when axonemes are otherwise defective (examples shown in online Fig. S1).

|

Table 2. Attachment of outer dynein arms (ODA) but not inner dynein arms (IDA) requires glycine at position 56 in the internal variable region.

Numbers in parentheses show total axonemes scored; followed by the number of males represented. B2t6 is identical to wild type β2 except for a glycine to aspartic acid substitution at position 56 (Table 1).

| β-tubulin in axonemes: | Wild type β2 (138; 14)1 | B2t6 (100; 13)2 | Equal amounts B2t6 and wild type β2 (111; 14)3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. No. ODA/Axoneme: | 8.98 | 3.2 | 8.4 |

| Avg. No. IDA/Axoneme: | 8.98 | 8.7 | 8.8 |

Data includes males with one gene copy and males with two gene copies. Of 74 axonemes in 10 males with only one copy of the β2 gene, average ODA per axoneme was 8.96; IDA, 8.96. Of 64 axonemes in 4 males with two copies of the β2 gene, average ODA was 9.0; IDA, 9.0. Both genotypes make normal functional sperm and are fertile [20, 22, 24, 25].

Data are for homozygous B2t6 males (two copies of B2t6). Range in average ODA/axoneme among individual males was 1.0 – 5.4; for IDA, 7.5 – 9. Homozygous B2t6 males make axonemes but do not produce functional sperm [26, 27]. Hemizygous males with only one copy of B2t6 and no other axoneme β-tubulin make many fewer intact axonemes, but attachment of dynein arms was the same as in B2t6 homozygotes (of 23 axonemes in 4 hemizygous males, average ODA was 3.1; IDA, 8.8; see Table S1).

B2t6 heterozygotes have 1 copy B2t6 and 1 copy wild type β2; their germ line β-tubulin pool consists of 50% mutant β26 and 50% wild type β2. Both β-tubulins are equally co-assembled into functional sperm [22, 26, 27]. Range in average ODA/axoneme among individual males was 7.3 – 9; for IDA: 7.8 – 9. See online Table S1 for additional data.

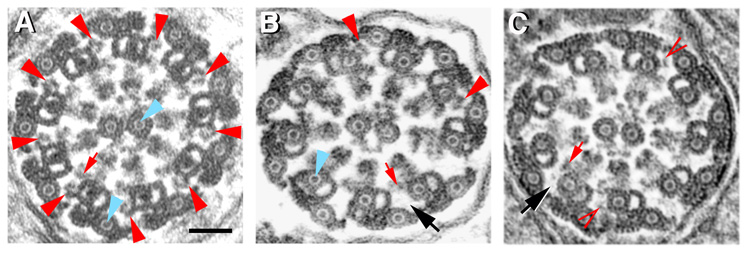

Fig. 1. Many sperm axoneme doublets lack outer dynein arms in B2t6 males.

(A) Mature sperm axoneme in a wild type male. All doublets have well-formed hook shaped ODAs (red arrowheads), and all doublets have inner dynein arms (IDAs; example indicated by small red arrow). Central pair and accessory microtubules have luminal filaments (examples indicated by blue arrowheads). (B, C) Axonemes from sterile B2t6 males. (B) Axoneme with two ODAs (red arrowheads). (C) Axoneme with no normal ODAs and two possible partial ODAs (open red arrowheads). Black arrows in B and C show examples of positions where an ODA should be, but is not. Doublets in B2t6 axonemes have IDAs (examples indicated by small red arrows in B and C), and luminal filaments (example indicated by blue arrowhead in B), similar to luminal filaments normally only in central pair and accessory microtubules. Scale bar, 50 nm.

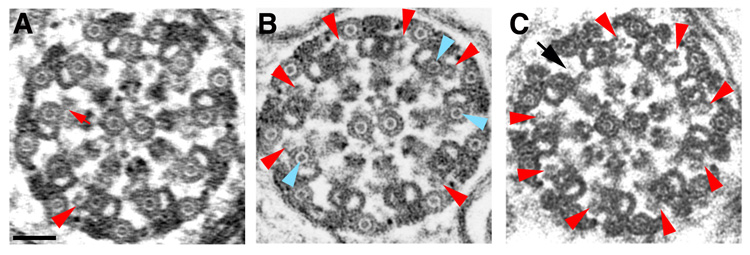

We have previously shown that the B2t6 mutation also has another phenotype. In addition to the classic “9+2” pattern, insect sperm axonemes have an outer ring of nine accessory microtubules, each associated with one of the doublets. Accessory and central pair microtubules contain a luminal filament, appearing as a “dot” in cross-section (Fig. 1A). In B2t6 males, the A-tubules of most doublets also contain luminal filaments (Figs. 1B, C; Table S1) [26, 27]. In Drosophila spermatogenesis, addition of dynein arms precedes appearance of luminal filaments in the central pair and accessory microtubules. Therefore it was unlikely that the failure to add ODAs is secondary to adding luminal filaments to doublet microtubules. We were able to clearly demonstrate that the two phenotypes are independent, separable events by using males co-expressing the chimeric protein β3β2C along with wild type β2. β3β2C, which has the β3 IVR containing nine instead of three amino acids (Table 1) has a phenotype very similar to that of B2t6, but in contrast to the recessive point mutation, β3β2C is strongly dominant [20]. We could control the ratio of the two proteins present in the male germ line by generating males expressing different copy numbers of β3β2C and β2. Strikingly, this allowed us to titrate ODAs. Addition of ODAs depended on the percent of β3β2C in the total β2-tubulin pool (Table 3; Fig. 2), confirming the role of the IVR in determining ODA addition. Moreover, axoneme morphology in β3β2C-expressing males conclusively showed that addition of ODAs and luminal filaments in the doublet microtubules occur independently. In axonemes of males with 33% β3β2C, some doublets lack ODAs and some doublets are filled, but the two phenotypes are not linked (Fig. 2B; Table S1).

Table 3. Addition of outer dynein arms in axonemes of males that co-express β3β2C and wild type β2 depends on the percent β3β2C.

Numbers in parentheses show total axonemes scored; followed by the number of males represented in sample. In all cases, both β-tubulins were co-assembled into axonemes in the same proportion they represented in the β2-tubulin pool [20, 22]. See online Table S1 for additional data.

| Percent β3β2C: | 50% (50; 4) | 33% (105; 6) | 25% (46; 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average No. ODA/Axoneme: | 1.7 | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Average No. IDA/Axoneme: | 8.8 | 8.96 | 8.96 |

Fig. 2. β3β2C inhibits addition of outer dynein arm when co-expressed with β2.

(A) Axoneme with 50% β3β2C. Only one doublet has an ODA (red arrowhead). A-tubules of all doublets have luminal filaments. (B) Axoneme with 33% β3β2C. Six doublets have outer dynein arms (red arrowheads); three doublets have filled A-tubules (blue arrowheads). All four possible arrangements for ODAs and filled doublets are present: four doublets have ODAs and are not filled (normal); two have ODAs but are filled; two lack ODAs but are not filled; one lacks an ODA and is filled. (C) Axoneme with 25% β3β2C. Most doublets have ODAs (red arrowheads; black arrow indicates single missing ODA). None of the doublets are filled. All doublets in A–C have IDAs (example indicated by small red arrow in A). Scale bar, 50 nm.

ODA addition is independent of CTT sequence. Both B2t6 and β3β2C have the wild type β2 C-terminus. We also examined ODAs in males that co-expressed the parent β3 molecule along with β2. Sperm axonemes of these males exhibited the same ODA phenotype as the chimeric β3β2C protein (Table S1). We note that while addition of ODAs is independent of C-terminal sequences, other aspects of axoneme functionality, reflected in male fertility, strongly depend on the CTT ([20], Table S1).

The phenotype of sperm axonemes in males that co-express the moth Heliothus virescens β2 homolog along with Drosophila β2 provides another indicator of the specificity of the influence of the IVR on ODA addition. H. virescens β2 causes even stronger dominant disruption of Drosophila spermatogenesis than β3β2C or β3, severely disrupting axonemes if it comprises 10% or more of the male germ line β-tubulin pool. In sperm axonemes of such males, the presence of moth β2 strikingly confers moth-like morphology to the accessory microtubules [21]. However, H. virescens β2 has glycine 56 in the IVR, and even fragmented or partial axonemes have ODAs on the doublets (Table 1; Fig. S1).

The internal axoneme sequence signature is conserved in all axonemal β-tubulins

Sequence comparisons revealed that glycine 56 is invariant in all known axonemal β-tubulins (Table 4; Table S2). Our data thus strongly support the hypothesis that stable attachment of outer arms depends on the sequence in the β-tubulin internal variable region in all motile axonemes with ODAs. Moreover, the entire axonemal β-tubulin IVR is conserved, with a consensus sequence of TGG (Table 4). In contrast, non-axonemal β-tubulins exhibit a range of amino acids at all positions in the IVR.

Table 4. Axonemal β-tubulins have glycine at the middle position of the internal variable region.

Amino acids that occur at each position in the IVR are tabulated for 34 axonemal and 40 non-axonemal β-tubulins; subscripts show the number of times a given amino acid occurs at each position in the β-tubulins sampled. Sequences represent β-tubulins in 58 genera encompassing animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Data and references are provided online in Table S2.

| Amino acids in the IVR: | 55 | 56 | 57 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axonemal β-tubulins: | T24 S7 A3 | G34 | G32 A1 S1 |

| Non-axonemal β-tubulins:* | S19 T7 A6 G4 Y3 R1 | G25 S6 C5 A2 N1 D1 | G22 N11 H2 S1 Q1 K1 R1 A1 |

Conclusions

Electron tomography indicates that ODAs contact the A-tubule through at least three interfaces, two of which involve proteins identified as part of the ODA docking complex [5]. Other components at the base of the arm have been shown to contact tubulins [5, 7, 28], but the specific tubulin residues involved have not been previously known. Our demonstration of the crucial role for β-tubulin glycine 56 and the conserved axonemal IVR provides the first identification of a specific tubulin sequence required for association of ODAs with axoneme doublets. β-tubulin amino acid 56 lies on the surface of the microtubule facing the lumen [6, 29]. Specific interactions with this region of tubulin are not defined. However, the open nature of the microtubule lattice [8, 29] means that the microtubule lumen is accessible to proteins outside the microtubule. Recent studies of doublets in sea urchin sperm and Chlamydomonas flagella indicate several structures inside the microtubule luminal surface [3, 4], the positions of which suggest they may help to stabilize the doublet or anchor proteins that attach to the outside of the microtubules. The presence of glycine at position 56 of the β-tubulin IVR may determine necessary conformation to permit these associations. Alternatively, there may be sequence-specific interactions between glycine 56 and protein(s) involved in ODA attachment. Because some ODAs remain present even in B2t6 mutant males (Table 1), the role of glycine 56-mediated interactions may be in the efficiency or stability of ODA attachment. The remarkable conservation of the IVR region in all axonemal β-tubulins suggests that the mechanism for ODA attachment is also conserved, consistent with the conservation of some of the proteins of the outer arm docking complex [13, 14]. Several luminal structures, including the luminal filaments in Drosophila sperm axoneme central pair and accessory microtubules, are added after microtubule construction [3, 4, 20, 21, 26, 30]. In B2t6 and β3β2C males, mislocation or absence of some of the normal luminal proteins in the doublet microtubules might be a factor in the incorrect addition of luminal filaments into doublet microtubules.

A key question is whether the conserved sequence of the axonemal β-tubulin IVR reflects its importance for any other aspect of axoneme structure or function. Motile axonemes lacking outer dynein arms occur naturally in sperm of eels [31]; in some insect sperm, including caddisflies and mayflies [32]; and in the flagellated sperm of basal non-angiosperm land plants, including gingko, cycads, ferns, lycophytes, and bryophytes [33, 34]. Outer arm dynein genes are not present in the genomes of the fern Marsilea [1] and the moss Physcomitrella [35]. The evolutionary loss of ODAs in diverse phylogenetic groups potentially provides a test of whether the IVR sequence remains constrained in the absence of the need for attachment of the ODAs. There is as yet insufficient data. However, the IVR is SGG in the two plant species with motile gametes for which complete presumptive axoneme β-tubulin sequences are available (Table S2), suggestive of constraint.

Experimental Procedures

Axoneme morphology was scored in electron micrographs of cross sections of spermatids in testes. Only axonemes in sufficiently good cross section such that all doublets and associated features were clearly discernable were scored. Although dynein arms and other axoneme-associated structures are present in fragmented or partial axonemes (see Fig. S1), only intact axonemes with 9 outer doublets were scored, to be sure that absence of outer arms was not a consequence of fragmentation of axonemes. In Drosophila spermatogenesis, outer and inner dynein arms are added to axonemes prior to or during early stages of assembly of the accessory microtubules. Therefore, we scored only axonemes in which all accessory microtubules were present and the majority were closed, or in mature axonemes, i.e., at stages when we could be confident ODAs would be present in wild type axonemes (see [20] for stages in Drosophila axoneme maturation and [21] for mode of assembly of accessory microtubules). Both ODAs and inner dynein arms were scored, to be sure absence of ODAs in experimental genotypes was not due in whole or in part to fixation or plane of sectioning. Normal ODAs have a distinct hook shape in cross section (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2, S1); we scored ODAs as present if a significant projection was present in the correct position, even if the full hook-like morphology wasn’t present.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Joan Caulton for her contributions to electron microscopy of axonemes, and Michael Prigge for his help with plant β-tubulins. This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM56493 to E.C.R.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wickstead B, Gull K. Dyneins across eukaryotes: a comparative genomic analysis. Traffic. 2007;8:1708–1721. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takada S, Kamiya R. Functional reconstitution of Chlamydomonas outer dynein arms from alpha-beta and gamma subunits: requirement of a third factor. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:737–745. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicastro D, Schwartz C, Pierson J, Gaudette R, Porter ME, McIntosh JR. The molecular architecture of axonemes revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science. 2006;313:944–948. doi: 10.1126/science.1128618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sui H, Downing KH. Molecular architecture of axonemal microtubule doublets revealed by cryo-electron tomography. Nature. 2006;442:475–478. doi: 10.1038/nature04816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishikawa T, Sakakibara H, Oiwa K. The architecture of outer dynein arms in situ. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1249–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Downing KH. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 1998;391:199–203. doi: 10.1038/34465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oda T, Hirokawa N, Kikkawa M. Three-dimensional structures of the flagellar dynein-microtubule complex by cryoelectron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:243–252. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meurer-Grob P, Kasparian J, Wade RH. Microtubule structure at improved resolution. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8000–8008. doi: 10.1021/bi010343p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satir P. Studies on cilia. 3. Further studies on the cilium tip and a "sliding filament" model of ciliary motility. J. Cell Biol. 1968;39:77–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.39.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gee MA, Heuser JE, Vallee RB. An extended microtubule-binding structure within the dynein motor domain. Nature. 1997;390:636–639. doi: 10.1038/37663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audebert S, White D, Cosson J, Huitorel P, Edde B, Gagnon C. The carboxy-terminal sequence Asp427-Glu432 of beta-tubulin plays an important function in axonemal motility. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;261:48–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vent J, Wyatt TA, Smith DD, Banerjee A, Luduena RF, Sisson JH, Hallworth R. Direct involvement of the isotype-specific C-terminus of beta tubulin in ciliary beating. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4333–4341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takada S, Wilkerson CG, Wakabayashi K, Kamiya R, Witman GB. The outer dynein arm-docking complex: composition and characterization of a subunit (oda1) necessary for outer arm assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1015–1029. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-04-0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushimaru Y, Konno A, Kaizu M, Ogawa K, Satoh N, Inaba K. Association of a 66 kDa homolog of Chlamydomonas DC2, a subunit of the outer arm docking complex, with outer arm dynein of sperm flagella in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Zoolog. Sci. 2006;23:679–687. doi: 10.2108/zsj.23.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freshour J, Yokoyama R, Mitchell DR. Chlamydomonas flagellar outer row dynein assembly protein ODA7 interacts with both outer row and I1 inner row dyneins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:5404–5412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607509200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koutoulis A, Pazour GJ, Wilkerson CG, Inaba K, Sheng H, Takada S, Witman GB. The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ODA3 gene encodes a protein of the outer dynein arm docking complex. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1069–1080. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakabayashi K, Takada S, Witman GB, Kamiya R. Transport and arrangement of the outer-dynein-arm docking complex in the flagella of Chlamydomonas mutants that lack outer dynein arms. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2001;48:277–286. doi: 10.1002/cm.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan KF. Structure and utilization of tubulin isotypes. Ann. Rev. Cell. Biol. 1988;4:687–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fackenthal JD, Turner FR, Raff EC. Tissue-specific microtubule functions in Drosophila spermatogenesis require the β2-tubulin isotype-specific carboxy terminus. Dev. Biol. 1993;158:213–227. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyle HD, Hutchens JA, Turner FR, Raff EC. Regulation of beta-tubulin function and expression in Drosophila spermatogenesis. Dev. Genet. 1995;16:148–170. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020160208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raff EC, Fackenthal JD, Hutchens JA, Hoyle HD, Turner FR. Microtubule architecture specified by a beta-tubulin isoform. Science. 1997;275:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoyle HD, Turner FR, Brunick L, Raff EC. Tubulin sorting during dimerization in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2185–2194. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen MG, Turner FR, Hutchens JA, Raff EC. Axoneme-specific beta-tubulin specialization: a conserved C-terminal motif specifies the central pair. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:529–533. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popodi EM, Hoyle HD, Turner FR, Raff EC. The proximal region of the beta-tubulin C-terminal tail is sufficient for axoneme assembly. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2005;62:48–64. doi: 10.1002/cm.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popodi EM, Hoyle HD, Turner FR, Xu K, Kruse S, Raff EC. Axoneme specialization embedded in a "Generalist" beta-tubulin. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:216–237. doi: 10.1002/cm.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fackenthal JD, Hutchens JA, Turner FR, Raff EC. Structural analysis of mutations in the Drosophila β2-tubulin isoform reveals regions in the beta-tubulin molecular required for general and for tissue-specific microtubule functions. Genetics. 1995;139:267–286. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuller MT, Caulton JH, Hutchens JA, Kaufman TC, Raff EC. Mutations that encode partially functional beta 2 tubulin subunits have different effects on structurally different microtubule arrays. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:141–152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkerson CG, King SM, Koutoulis A, Pazour GJ, Witman GB. The 78,000 M(r) intermediate chain of Chlamydomonas outer arm dynein is a WD-repeat protein required for arm assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:169–178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nogales E, Whittaker M, Milligan RA, Downing KH. High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell. 1999;96:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaughan S, Shaw M, Gull K. A post-assembly structural modification to the lumen of flagellar microtubule doublets. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R449–R450. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons BH, Gibbons IR, Baccetti B. Structure and motility of the 9 + 0 flagellum of eel spermatozoa. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. 1983;15:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afzelius BA, Bellon PL, Dallai R, Lanzavecchia S. Diversity of microtubular doublets in insect sperm tails: a computer-aided image analysis. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1991;19:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyams JS, Campbell CJ. Widespread absence of outer dynein arms in the spermatozoids of lower plants. Cell. Biol. Int. Rep. 1985;9:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(85)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renzaglia KS, Garbary DJ. Motile gametes of land plants: diversity, development, and evolution. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2001;20:107–213. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rensing SA, Lang D, Zimmer AD, Terry A, Salamov A, Shapiro H, Nishiyama T, Perroud PF, Lindquist EA, Kamisugi Y, et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science. 2008;319:64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1150646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudolph JE, Kimble M, Hoyle HD, Subler MA, Raff EC. Three Drosophila beta-tubulin sequences: a developmentally regulated isoform (beta 3), the testis-specific isoform (beta 2), and an assembly-defective mutation of the testis-specific isoform (B2t8) reveal both an ancient divergence in metazoan isotypes and structural constraints for beta-tubulin function. Mol. Cell Biol. 1987;7:2231–2242. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.6.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michiels F, Falkenburg D, Muller AM, Hinz U, Otto U, Bellmann R, Glatzer KH, Brand R, Bialojan S, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Testis-specific beta 2 tubulins are identical in Drosophila melanogaster and D. hydei but differ from the ubiquitous beta 1 tubulin. Chromosoma. 1987;95:387–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00333989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoyle HD, Raff EC. Two Drosophila beta tubulin isoforms are not functionally equivalent. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:1009–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.