How did the study come about?

Given the dramatic decline in the incidence of HIV infection in infants and children in the United States, but the unfortunate persistence of mother to child transmission in other parts of the world, international collaborations are critical to the conduct of trials to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of therapeutic and prophylactic modalities in children. Additionally, because the bulk of pediatric HIV infection now occurs in middle- and low-income countries, infrastructure development in such countries is also very important. With the advent and availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the face of this fatal disease in children has changed from one of widespread morbidity and mortality to one that is potentially manageable and allows infected children to survive well into adulthood.1,2 Because of these changes, the importance of long-term outcomes related to both the disease and exposure to its treatment has become a major focus of research efforts.

Through experience with pediatric antiretroviral (ARV) treatment trials in sites in Brazil and The Bahamas in 1998 and 1999, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) identified a need to increase Latin American and Caribbean capacity for the conduct of clinical trials, particularly those involving experimental drugs in HIV-infected children. During 2000, NICHD began the NICHD International Site Development Initiative (NISDI) in Latin America and the Caribbean to address this need. NISDI was designed to provide capacity-building and training to international sites through the conduct of two observational studies: the perinatal protocol that enrolled HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants,3 and the pediatric protocol that enrolled HIV-exposed, but uninfected infants and HIV-infected infants, children and adolescents. This initiative provided direct training and capacity-building for sites with limited prior experience in conducting clinical trials, by involving these sites in the development of protocols and informed consent documents, managing data collection and transmittal, performing virologic and immunologic laboratory testing and other study-related activities and participating in the analysis and reporting of study findings. A major goal of this initiative was to train investigators and develop sites that could then participate in future prevention and treatment trials within international and regional networks.

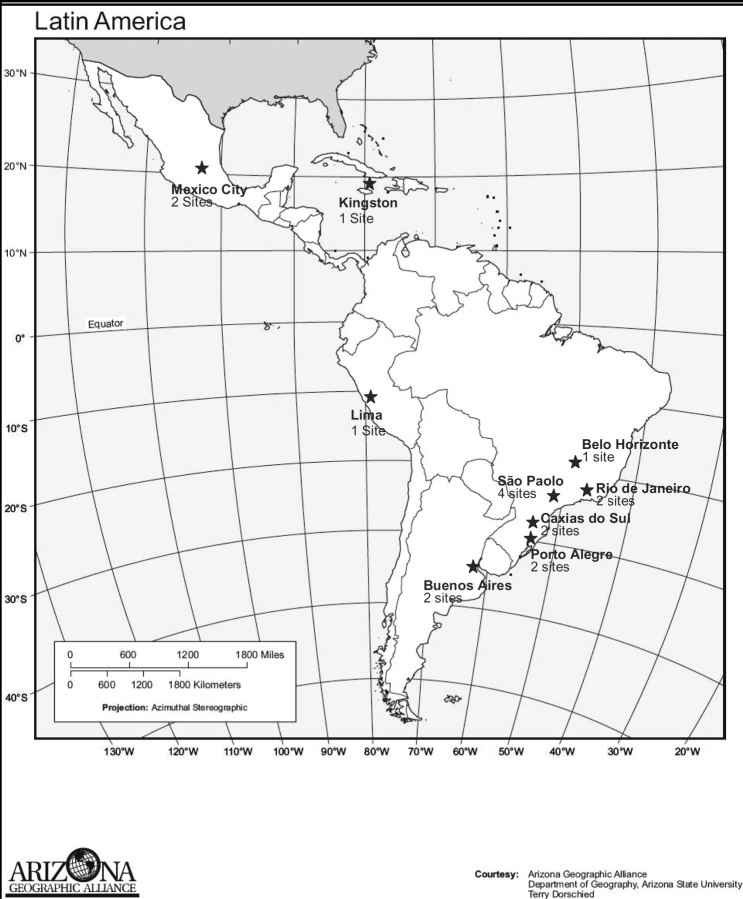

NICHD and the data management and statistical centre developed and released a Request for Proposals for Latin American and Caribbean sites in November 2000, soliciting potential investigators and sites in a systematic fashion through communication with regional and national public health and AIDS offices, professional organizations and universities. To be eligible to participate, sites were required to follow at least 30 HIV-infected and exposed children <21 years old and have ARVs available for patients who met criteria for treatment as determined by clinical practice at each site. ARV treatment was not provided by the protocol and initiation and management of ARVs were decided by individual site investigators as per availability, clinical practice at that site and national guidelines. Alternatives to breastfeeding were also required but not provided by the protocol. Sites were required to provide a subject retention plan, to demonstrate the ability to perform basic laboratory assays and the capability to perform CD4 and HIV viral load assays either on site or through a laboratory routinely used by the site, and to have access to freezers for storage of repository samples. Given the selection criteria, centres chosen to participate in the study had either carried out research in the past or had sufficient infrastructure in place to carry out research. An external review committee made up of international experts in HIV-infection reviewed proposals and made recommendations about site selection in 2001. Approximately half of the sites that submitted proposals were chosen. The data management and statistical centre subcontracted with 15 sites in three countries (Brazil, Mexico and Argentina) to carry out the pediatric protocol. During 2001 and 2002, NICHD and Westat staff and investigators from each site developed the study protocol. Subsequently, the NICHD Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Westat IRB, separate in-country ethics committees and national review boards (where appropriate, i.e. Brazil) reviewed and approved the protocol. In 2006, two additional sites were added, one in Peru and one in Jamaica. The geographical locations of the sites are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the 17 sites participating in the NISDI pediatric collaboration

What does it cover and who is in the sample?

The scientific goals of the pediatric protocol are: (i) to describe the characteristics of HIV-exposed infants and HIV-infected infants, children and adolescents cared for at clinical sites in Latin America and the Caribbean, (ii) to describe early and late outcomes related to HIV disease and ARV therapy and (iii) to describe early and late outcomes related to in utero exposure to ARVs and HIV and to neonatal exposure to ARVs.

When enrolment began in the autumn of 2002, two groups of subjects who were receiving care at the participating sites (11 in Brazil and 2 each in Mexico and Argentina) were eligible: (i) infants (≤12 months of age) who were born to women diagnosed with HIV infection either prior to or during pregnancy or within 1 month postpartum and (ii) HIV-infected infants, children and adolescents (≤21 years of age). All subjects with vertically acquired HIV infection and all those determined to be HIV negative (or indeterminate) were born to HIV-infected mothers. The subjects with horizontally acquired HIV infection had to have another mode of transmission and/or not be born to an HIV-infected mother. Informed consent was obtained from either parents or guardians or from subjects who were able to provide consent based upon local laws. Assent was obtained from subjects >8 years of age when appropriate and according to local practice.

By 2004, the enrolment rate was higher than anticipated (922 enrolled, accrual ceiling of 1500), and the protocol was amended to increase the accrual ceiling to 2000, to close new enrolment at five of the Brazilian sites (but to continue enrolled subject follow-up at those sites), and to limit new enrolment of HIV-infected infants and children at other sites to those who were <5 years of age. We now report data collected by October 2007.

How often have patients been followed up and what is measured?

The following were performed at 6 month intervals: medical history (including diagnoses, hospitalizations, medications and vaccinations), physical examination, laboratory evaluations (including haematology, flow cytometry and standard biochemical assays), growth parameters, morbidity evaluation and mortality status. Virologic assessments were performed in the HIV-infected group. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and plasma were collected from all subjects annually and stored in a central repository for potential future studies.

What has been found?

As shown in Table 1, 1629 subjects enrolled of whom 731 (45%) were vertically HIV-infected, 85 (5%) horizontally HIV-infected, 767 (47%) confirmed to be HIV-uninfected and 46 (3%) whose HIV status was indeterminate as of October 2007. Eight hundred and sixteen were enrolled in the first year of life, the vast majority of whom were HIV-uninfected. The majority of subjects (70%) were enrolled in Brazil and 15% were enrolled in Argentina. In a majority (88%) of the HIV-infected mothers, HIV was transmitted via heterosexual contact. Injection drug use was a risk factor for HIV acquisition in 7.9% of HIV-infected mothers who had an HIV-infected child, compared with 2.7% of HIV-infected mothers with an uninfected child (P < 0.0001). There was one HIV-infected mother who was infected perinatally. As expected, the vast majority (93%) of the mothers of HIV-uninfected subjects received ARV prophylaxis or treatment during pregnancy. The regimen included a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) and/or a protease inhibitor (PI) in 82% of the group that received ARVs. Only 11% of the mothers of HIV-infected subjects received an ARV regimen during pregnancy and only 25% of these mothers receiving ARVs received an NNRTI and/or a PI. Sixty-two per cent of the HIV-uninfected subjects were delivered by Caesarean section; whereas, only 33% of the HIV-infected subjects were delivered in this manner (P < 0.0001). These differences may reflect different availability and standards of management in different time periods when subjects were born; the entire HIV-uninfected cohort was born recently, whereas the HIV-infected cohort was generally much older. Among the subjects with HIV-infected mothers, 49% were primarily cared for by both biological parents, and the biological mother alone was the primary caregiver for an additional 32%.

Table 1.

Enrolment by age and HIV status

| Age at enrolment (years) | HIV Infection Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-infected vertical | HIV-infected horizontal | HIV-uninfected | HIV indeterminate | Total | |

| <1 | 33 | 0 | 737 | 46 | 816 |

| 1 ≤ 2 | 47 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 78 |

| 2–4 | 226 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 238 |

| 5–10 | 323 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 342 |

| 11+ | 102 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 155 |

| Total | 731 (44.9%) | 85 (5.2%) | 767 (47.1%) | 46 (2.8%) | 1629 |

Among all of the HIV-infected subjects (horizontally and vertically infected), 30%, 26%, 32% and 12% had HIV RNA levels <500 copies/ml, between 500 and 9999 copies/ml, between 10 000 and 99 999 copies/ml, and ≥100 000 copies/ml, respectively, at enrolment. Only 12% had CD4% <15 at enrolment, while 59% had CD4% ≥25.

The characteristics of the 85 horizontally infected subjects are shown in Table 2. Thirty-two acquired HIV through consensual sexual contact, 19 via blood transfusion, while 31 had no known risk factors. In general, this was a relatively healthy group with 58% having CD4% ≥25, 35% having HIV RNA levels <500 copies/ml and 35% receiving no ARVs at the time of enrolment.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the horizontally HIV-infected group at enrolment (N = 85)

| Gender–No. (%) | |

| Female | 46 (54.1) |

| Mode of HIV acquisition—No. (%) | |

| Blood product transfusion | 19 (22.4) |

| Consensual sexual contact | 32 (37.6) |

| No known risk factors | 31 (36.5) |

| Other | 1 (1.2) |

| Sexual abuse | 1 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.2) |

| CD4% at enrolment—No. (%) | |

| <15% | 12 (15.6) |

| 15–24% | 20 (26.0) |

| ≥25% | 45 (58.4) |

| Missinga | 8 |

| HIV RNA copies/ml at enrolment—No. (%) | |

| <500 | 29 (35.4) |

| 500–9999 | 24 (29.3) |

| 10 000–99 999 | 28 (34.1) |

| ≥100 000 | 1 (1.2) |

| Missinga | 3 |

| Type of ARV regimen received at enrolment—No. (%) | |

| No ARV | 30 (35.3) |

| NRTI-based only | 7 (8.2) |

| PI-based HAART | 27 (31.8) |

| NNRTI-based HAART | 16 (18.8) |

| PI + NNRTI-based HAART | 5 (5.9) |

aNot included in % calculation.

The characteristics of the 731 vertically infected subjects are shown in Table 3. Sixty per cent had CD4% ≥25, 29% had HIV RNA <500 copies/ml and 84% were receiving ARVs at the time of enrolment. Seventy-nine per cent of those receiving ARVs at enrolment were receiving HAART, i.e. a regimen that contained an NNRTI and/or a PI. A list of the individual regimens received by three or more subjects at enrolment is shown in Table 4. A total of 106 children were ARV naïve at enrolment (25 of these 106 had received ARV prophylaxis). Sixty-three of these treatment naïve subjects started ARVs during the study. Most subjects’ HIV disease laboratory parameters remained stable through 18 months as evidenced by 66% having CD4% ≥25 and 38% having HIV RNA <500 copies/ml at 18 months of follow-up. Eighteen subjects died during the study, 16 of whom were HIV-infected. Characteristics of the subjects who died are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the vertically infected group at enrolment and after 18 months of follow-up (N = 731)

| <2 years | 2–4 years | 5–10 years | 11–21 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 47 (58.8) | 117 (51.8) | 180 (55.7) | 62 (60.8) | 406 (55.5) |

| Male | 33 (41.2) | 109 (48.2) | 143 (44.3) | 40 (39.2) | 325 (44.5) |

| ARV received by mother during pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 30 (39.0) | 30 (14.9) | 20 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 80 (13.1) |

| No | 47 (61.0) | 171 (85.1) | 242 (92.4) | 72 (100) | 532 (86.9) |

| Unknown | 3 | 25 | 61 | 30 | 119 |

| HIV RNA copies/ml at enrolment | |||||

| <500 | 17 (21.8) | 60 (26.9) | 100 (31.0) | 33 (32.4) | 210 (28.9) |

| 500–9999 | 15 (19.2) | 45 (20.2) | 93 (28.8) | 31 (30.4) | 184 (25.3) |

| 10 000–99 999 | 15 (19.2) | 79 (35.4) | 105 (32.5) | 33 (32.4) | 232 (32.0) |

| ≥100 000 | 31 (39.7) | 39 (17.5) | 25 (7.7) | 5 (4.9) | 100 (13.8) |

| Missing | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| HIV RNA copies/ml at 18 months | |||||

| <500 | 20 (37.7) | 67 (37.6) | 115 (36.9) | 41 (40.2) | 243 (37.7) |

| 500–9999 | 11 (20.8) | 44 (24.7) | 99 (31.7) | 31 (30.4) | 185 (28.7) |

| 10 000–99 999 | 16 (30.2) | 53 (29.8) | 80 (25.6) | 26 (25.5) | 175 (27.1) |

| ≥100 000 | 6 (11.3) | 14 (7.9) | 18 (5.8) | 4 (3.9) | 42 (6.5) |

| Missing | 27 | 48 | 11 | 0 | 86 |

| CD4% results at enrolment | |||||

| <15% | 9 (12.2) | 23 (11.6) | 29 (10.4) | 13 (14.0) | 74 (11.5) |

| 15–24% | 19 (25.7) | 54 (27.3) | 73 (26.1) | 41 (44.1) | 187 (29.0) |

| ≥25% | 46 (62.2) | 121 (61.1) | 178 (63.6) | 39 (41.9) | 384 (59.5) |

| Missing | 6 | 28 | 43 | 9 | 86 |

| CD4% results at 18 months | |||||

| <15% | 2 (3.8) | 7 (4.0) | 24 (8.1) | 15 (15.5) | 48 (7.8) |

| 15–24% | 9 (17.0) | 36 (20.8) | 80 (27.1) | 36 (37.1) | 161 (26.1) |

| ≥25% | 42 (79.2) | 130 (75.1) | 191 (64.7) | 46 (47.4) | 409 (66.2) |

| Missing | 27 | 53 | 28 | 5 | 113 |

| CDC Clinical Classification at enrolment | |||||

| C | 22 (31.0) | 82 (36.3) | 102 (31.6) | 27 (26.5) | 233 (32.3) |

| B | 13 (18.3) | 67 (29.6) | 112 (34.7) | 41 (40.2) | 233 (32.3) |

| A/N | 36 (50.7) | 77 (34.1) | 109 (33.7) | 34 (33.3) | 256 (35.5) |

| Missing | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| CDC clinical classification at 18 months | |||||

| C | 26 (32.5) | 85 (37.6) | 103 (31.9) | 29 (28.4) | 243 (33.2) |

| B | 21 (26.3) | 69 (30.5) | 118 (36.5) | 41 (40.2) | 249 (34.1) |

| A/N | 33 (41.3) | 72 (31.9) | 102 (31.6) | 32 (31.4) | 239 (32.7) |

| Child's ARV regimen at enrolment | |||||

| No ARV | 35 (43.8) | 49 (21.7) | 29 (9.0) | 5 (4.9) | 118 (16.1) |

| NRTI-based only | 12 (15.0) | 27 (11.9) | 65 (20.1) | 24 (23.5) | 128 (17.5) |

| PI-based HAART | 28 (35.0) | 107 (47.3) | 146 (45.2) | 45 (44.1) | 326 (44.6) |

| NNRTI-based HAART | 5 (6.3) | 33 (14.6) | 51 (15.8) | 13 (12.7) | 102 (14.0) |

| PI + NNRTI-based HAART | 0 (0.0) | 10 (4.4) | 31 (9.6) | 14 (13.7) | 55 (7.5) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Type of ARV regimen received at 18 months | |||||

| No ARV | 8 (14.5) | 26 (14.6) | 15 (4.8) | 6 (5.9) | 55 (8.5) |

| NRTI-based only | 9 (16.4) | 21 (11.8) | 54 (17.1) | 19 (18.6) | 103 (15.8) |

| PI-based HAART | 32 (58.2) | 89 (50.0) | 156 (49.5) | 48 (47.1) | 325 (50.0) |

| NNRTI-based HAART | 6 (10.9) | 34 (19.1) | 64 (20.3) | 18 (17.6) | 122 (18.8) |

| PI + NNRTI-based HAART | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.5) | 26 (8.3) | 11 (10.8) | 45 (6.9) |

| Missing | 25 | 48 | 8 | 0 | 81 |

Table 4.

ARV regimens received by 3 or more of the 731 vertically infected subjects at enrolment

| ARV Regimena | N (%) |

|---|---|

| ZDV + ddI | 75 (10.3) |

| d4T + 3TC + NFV | 49 (6.7) |

| ZDV + ddI + NFV | 43 (5.9) |

| d4T + 3TC + RTV | 35 (4.8) |

| ZDV + 3TC + NFV | 33 (4.5) |

| d4T + ddI + NFV | 30 (4.1) |

| d4T + ddI + EFV + NFV | 25 (3.4) |

| ZDV + 3TC + NVP | 24 (3.3) |

| ZDV + 3TC | 23 (3.1) |

| d4T + ddI + RTV + SQV | 22 (3.0) |

| ZDV + 3TC + LPV/RTV | 18 (2.5) |

| d4T + ddI + EFV | 16 (2.2) |

| ZDV + ddI + EFV | 15 (2.1) |

| ZDV + 3TC + RTV | 15 (2.1) |

| d4T + ddI + LPV/RTV | 14 (1.9) |

| ZDV + 3TC + EFV | 13 (1.8) |

| ZDV + ABC + 3TC | 13 (1.8) |

| d4T + ddI + RTV | 12 (1.6) |

| d4T + 3TC + LPV/RTV | 12 (1.6) |

| d4T + 3TC + EFV | 12 (1.6) |

| ZDV + ddI + RTV | 11 (1.5) |

| ZDV + ddI + LPV/RTV | 9 (1.2) |

| d4T + 3TC + EFV + NFV | 7 (1.0) |

| d4T + ddI + NVP | 7 (1.0) |

| d4T + 3TC + NVP | 7 (1.0) |

| ZDV + ddI + NVP | 6 (0.8) |

| ZDV | 5 (0.7) |

| d4T + ddI | 4 (0.5) |

| d4T + ddI + EFV + LPV/RTV | 3 (0.4) |

| d4T + 3TC + NVP + NFV | 3 (0.4) |

| ddI + 3TC + EFV + NFV | 3 (0.4) |

| d4T + ddI + ABC | 3 (0.4) |

| d4T + 3TC | 3 (0.4) |

| Others | 43 (5.9) |

| No ARVs | 118 (16.1) |

aKey to ARV drug names: ZDV, zidovudine; ddI, didanosine; d4t, stavudine; 3TC, lamivudine; NFV, nelfinavir; RTV, ritonavir; EFV, efavirenz; NVP, nevirapine; SQV, saquinavir; ABC, abacavir; LPV, lopinavir.

Table 5.

Deaths on study among HIV-infected subjects

| Vertically infected | Age at enrolment (years) | Age at death (years) | Last available CD4% | Last available HIV RNA (copies/ml) | Primary cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 3.2 | 5.3 | 23 | 125 000 | Septicemia/meningitis |

| No | 16.9 | 18.7 | 1 | 995 000 | Septicemia |

| Yes | 3.5 | 6.7 | 24 | 25 | Multiple organ system failure |

| Yes | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3 | 2090 | Septic shock |

| Yes | 19.1 | 21.7 | 1 | 75 000 | Pneumonia |

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.6 | 50 | 500 000 | Septic shock (Streptococcus pneumoniae) |

| Yes | 3.7 | 7.5 | 4 | 60 096 | Unknown |

| No | 20.7 | 23.4 | 27 | 17 676 | Post-operative sepsis |

| Yes | 11.8 | 15.5 | 4 | 372 000 | Fungemia (Candida) |

| Yes | 2.5 | 4.1 | 22 | 37 908 | HIV wasting and diarrhea (Cryptosporidium) |

| Yes | 1.1 | 2.2 | 16 | 20 465 | Pneumonia and congestive heart failure |

| Yes | 3.6 | 4.5 | 1 | 78 955 | Pneumonia |

| No | 1.7 | 2.7 | 8 | 5255 | Unknown |

| Yes | 2.0 | 2.1 | 16 | 136 479 | Pneumonia |

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0 | 174 257 | Pneumonia |

| Yes | 2.7 | 3.4 | 10 | 100 000 | Sepsis (S. pneumoniae) |

Table 6.

Deaths on study among HIV-uninfected subjects

| Age at enrolment (years) | Age at death (years) | Primary cause of death |

|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 1.3 | Head injury/trauma |

| 0.4 | 1.0 | Pneumonia |

What are follow-up and attrition like?

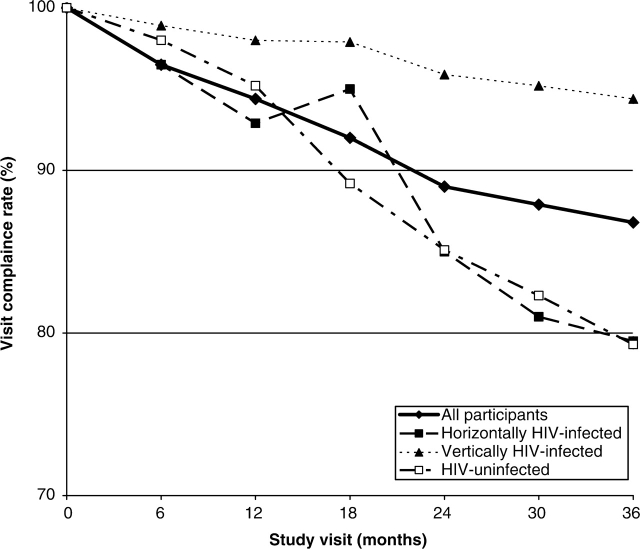

Median follow-up for all study subjects was ∼37 months with the HIV-infected subjects, both horizontally and vertically infected, having a median follow-up of >45 months. Visit compliance rates were calculated based on all those who completed a particular visit divided by those who were eligible for that visit. Overall and individual group visit compliance rates through 36 months are shown in Figure 2. As expected, the follow-up rates for the vertically infected subjects, who were actively receiving care at the sites in addition to their study evaluations, were very high, ranging from 94% to 99% at each scheduled visit. The data for the HIV-uninfected group have important implications, with follow-up rates ranging from 76% to 98%. Many recommend that follow-up of children with ARV exposure should continue into adulthood because of the theoretical concerns regarding the potential for carcinogenicity and mitochondrial toxicity from exposure to nucleoside analogue ARVs.4,5 According to the US Public Health Service guidelines,4 this long-term follow-up should include yearly physical examinations of all children exposed to ARVs. However, there are concerns about the feasibility of following large cohorts of uninfected children exposed to ARVs in utero or in the neonatal period since this group of children is generally healthy and not necessarily followed by a clinic engaged in pediatric HIV care. The rates in this protocol were reassuring in this regard and matched what was seen in an analysis from the US-based PACTG 219 study, which reported results on 234 uninfected children originally enrolled on the PACTG 076 trial6 and showed an 86% rate of retention.7

Figure 2.

Study visit compliance rates overall and by cohort

What are the main strengths and weaknesses of NISDI?

Strengths

Prospective, interval, cohort study in which data are collected at specific intervals as called for by a common protocol.

Centralized database.

Central sample repository for future studies in this well-characterized cohort (such as prevalence and impact of hyperlipidemia related to ARV exposure, genotypic characteristics of HIV resistance and profile of opportunistic infections).

Ongoing data quality review by data management and statistical centre with data issues and discrepancies resolved by clinical site.

Dedicated site investigators able and willing to propose and carry out individual secondary studies to answer specific scientific questions. These proposals are evaluated for scientific merit, feasibility and resource utilization and only meritorious proposals move forward.

Opportunities for collaborations between investigators from different regions within Brazil and different countries. These have been supported by annual NISDI meetings with site investigators.

Ability to collaborate with other pediatric cohorts, such as the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) and those being developed within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA),8 to pool data when large data sets are necessary to answer important scientific questions in a timely manner.

Weaknesses

Heavily weighted towards Brazil with limited participation of four other countries (Mexico, Argentina, Peru and Jamaica).

Subjects may not be a representative sample of the HIV-infected or exposed uninfected children at these sites or in these countries.

HIV-infected subjects with variable prior ARV treatment ranging from no history of ARVs to prior treatment with two or more regimens.

Historical data may be incomplete.

How can I collaborate? Where can I find out more?

Potential collaborators should contact the NICHD Principal Investigator (RH). Requests to access data and/or samples will be reviewed for scientific merit, feasibility and resource utilization by the NISDI Pediatric Executive Committee, which consists of five site investigators, a representative of the data management and statistical centre, and the NICHD Principal Investigator and other NICHD staff.

Funding

NICHD Contracts (#N01-HD-3-3345 and #N01-DK-8-0001).

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Appendix

The members of the NISDI Pediatric Study Group 2008 are: Principal investigators, co-principal investigators, study coordinators, data management centre representatives and NICHD staff include: Brazil: Belo Horizonte: Jorge Pinto, Flávia Faleiro (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais); Caxias do Sul: Ricardo da Silva de Souza, Nicole Golin, Machline Paim Paganella (Universidade de Caxias do Sul/Secretaria Municipal de DST/AIDS de Caxias do Sul-Ambulatório Municipal DST/AIDS); Nova Iguacu: Jose Pilotto, Beatriz Grinsztejn, Valdilea Veloso (Hospital Geral Nova de Iguacu Setor de DST/AIDS; Porto Alegre: Ricardo da Silva de Souza, Breno Riegel Santos, Rita de Cassia Alves Lira (Universidade de Caxias do Sul/Hospital Conceição); Ricardo da Silva de Souza, Mario Peixoto, Suzete Saraiva (Universidade de Caxias do Sul/Hospital Fêmina); Ricardo da Silva de Souza, Marcelo Goldani, Margery Bohrer Zanetello (Universidade de Caxias do Sul/Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre); Regis Kreitchman, Debora Coelho Fernandes (Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericordia de Porto Alegre); Ribeirão Preto: Marisa M. Mussi-Pinhata, Bento V. Moura Negrini, Maria Célia Cervi, Márcia L. Isaac (Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo); Rio de Janeiro: Ricardo Hugo S. Oliveira, Maria C. Chermont Sapia (Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira); Esau Custodio Joao, Maria Leticia Cruz, Claudete Araujo Cardoso, Guilherme Amaral Calvet (Hospital dos Servidores do Estado); São Paulo: Regina Celia de Menezes Succi, Daisy Maria Machado (Federal University of São Paulo); Marinella Della Negra, Wladimir Queiroz (Instituto de Infectologia Emilio Ribas); Mexico: Mexico City: Noris Pavía-Ruz, Patricia Villalobos-Acosta, Elsy Plascencia-Gómez (Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez); Peru: Lima: Jorge Alarcon (Instituto de Medicina Tropical ‘Daniel Alcides Carrion’-Division de Epidemiología), Maria Castillo Díaz (Instituto de Salud del Niño), Mary Felissa Reyes Vega (Instituto de Medicina Tropical ‘Daniel Alcides Carrion’-Division de Epidemiología); Data Management and Statistical Center: Yolanda Bertucci, Laura Freimanis Hance, René Gonin, D. Robert Harris, Roslyn Hennessey, Margot Krauss, James Korelitz, Sharon Sothern, Sonia K. Stoszek (Westat, Rockville, MD, USA); NICHD: Rohan Hazra, Lynne Mofenson, Jack Moye, Jennifer Read, Carol Worrell (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Maryland).

References

- 1.Gortmaker SL, Hughes M, Cervia J, et al. Effect of combination therapy including protease inhibitors on mortality among children and adolescents infected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1522–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K. The changing face of pediatric HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1568–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111223452111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Read JS, Cahn P, Losso M, et al. Management of human immunodeficiency virus-infected pregnant women at Latin American and Caribbean sites. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1358–67. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000265211.76196.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perinatal HIV Guidelines Working Group. Public Health Service Task Force Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. 2007. Nov 2, pp. 59–60. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PerinatalGL.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2008)

- 5.Spector SA, Saitoh A. Mitochondrial dysfunction: prevention of HIV-1 mother-to-infant transmission outweighs fear. AIDS. 2006;20:1777–78. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000242825.97495.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1173–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culnane M, Fowler M, Lee SS, et al. Lack of long-term effects of in utero exposure to zidovudine among uninfected children born to HIV-infected women. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 219/076 Teams. JAMA. 1999;281:151–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGowan CC, Cahn P, Gotuzzo E, et al. Cohort Profile: Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV research (CCASAnet) collaboration within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) programme. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:969–76. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]