Abstract

Two prospective investigations of the moderating role of dyadic friendship in the developmental pathway to peer victimization are reported. In Study 1, the preschool home environments (i.e., harsh discipline, marital conflict, stress, abuse, and maternal hostility) of 389 children were assessed by trained interviewers. These children were then followed into the middle years of elementary school, with peer victimization, group social acceptance, and friendship assessed annually with a peer nomination inventory. In Study 2, the home environments of 243 children were assessed in the summer before 1st grade, and victimization, group acceptance, and friendship were assessed annually over the next 3 years. In both studies, early harsh, punitive, and hostile family environments predicted later victimization by peers for children who had a low number of friendships. However, the predictive associations did not hold for children who had numerous friendships. These findings provide support for conceptualizations of friendship as a moderating factor in the pathways to peer group victimization.

There is considerable evidence that a small percentage of children are targeted for frequent physical and verbal abuse by their peers (Olweus, 1978; Perry, Kusel, & Perry, 1988; Perry, Perry, & Kennedy, 1992). Because these persistently victimized children are at risk for later psychosocial and behavioral maladjustment (Boivin, Hymel, & Bukowski, 1995; Schwartz, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1998), researchers have sought to examine the factors that potentially lead to such difficulties in the peer group. Within this domain of inquiry, the primary focus has been on identification of proximal predictors of peer group victimization. Investigators have examined direct predictive associations between behavioral or psychological vulnerabilities and victimization (Egan & Perry, 1998; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999; Hodges & Perry, 1999; Schwartz, Dodge, & Coie, 1993). Researchers have also begun to examine distal factors, such as early parenting and home environment (Bowers, Smith, & Binney, 1992, 1994; Ladd & Kochenderfer Ladd, 1998; Olweus, 1993) that are presumed to predict victimization through the mediation of more proximal mechanisms (Finnegan, Hodges, & Perry, 1998; Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997).

Early research on both the proximal and distal predictors of peer group victimization typically incorporated “main effect” models of risk. Such models are guided by the assumption that there are linear relations between a specific risk factor (or risk accrued additively from multiple factors) and particular negative outcomes. High levels of vulnerability or exposure to a risk factor are presumed to be linearly predictive of the undesired outcome. For example, investigators have described correlations between a child's propensity to submit to social overtures and the frequency with which that child is targeted for victimization by peers (e.g., Olweus, 1978; Schwartz, Dodge, et al., 1998). Frequent displays of submissive social behavior are presumed to lead directly to persistent victimization by peers (Schwartz et al., 1993).

More recently, investigation of the predictors of peer victimization has incorporated interactive models, which posit that the risk associated with particular vulnerabilities varies systematically as a function of the presence or absence of other factors (Rutter, 1989). Interactive models allow for “protector” variables that mitigate the impact of exposure to risk (e.g., Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997). Hodges, Malone, and Perry (1997) proposed such a model in regard to the proximal behavioral predictors of victimization. Hodges et al. (1997) hypothesized that friendship mitigates the relation between maladaptive behavioral propensities and peer group victimization. These researchers reported that the strength of the association between victimization and behavioral risk factors (assessed concurrently) is attenuated for children who are able to establish friendships with peers. Subsequent researchers have found that friendship exerts a longer term moderating influence on the behavioral pathways to victimization, although the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully understood (Schwartz, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999).

The current study extends this conceptualization of friendship as a moderating factor to a prospective investigation of the distal predictors of victimization. Our goal was to examine the influence of friendship on the link between early harsh home environments and later peer group victimization. We sought to determine whether the strength of the association between negative experiences in the home and bullying in the school peer group is diminished for children who have numerous friends.

We focused our analyses on aspects of early home experience linked to peer group victimization in the existing literature. In an earlier study (Schwartz et al., 1997), we reported that preschool exposure to harsh, punitive, or violent home environments is predictive of peer victimization for third- and fourth-grade boys, although our findings were restricted to victims who were concurrently aggressive. In past research, we have also found that early family exposure to major stressors (e.g., deaths in the family, financial and legal difficulties) is associated with later victimization in the peer group (Schwartz, 1993). Other family processes that have been linked to peer group victimization include parental hostility or rejection and maternal restrictiveness or over control (e.g., Finnegan et al., 1998; Olweus, 1993). We examined the moderating role of friendship on the predictive associations between these aspects of early experience in the home and later victimization by peers.

We hypothesized that harsh home environments lead children to react in volatile and out-of-control ways to later provocation, a pattern that is prone to “egg on” victimizers (Schwartz, Dodge, et al., 1998). We expected that friendship would moderate this predictive link by serving as an ameliorative factor. Past investigators have suggested that the beneficial effects of friendship can help children to compensate for vulnerabilities acquired through stressful experiences in the home (Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; Gauze, Bukowski, Aquan-Assee, & Sippola, 1996). Positive interactions with friends might alter problematic developmental trajectories (e.g., pathways between harsh home environment and peer victimization) by enhancing emerging capacities for self-regulation (Parker & Gottman, 1989) and by facilitating the development of other core social competencies (Price, 1996).

An alternative perspective offered by past researchers is that friends mitigate risk for victimization by providing vulnerable children (i.e., children who have deficits in behavioral and emotional control) with support against potential victimizers (Hodges et al., 1997). This hypothesized protective role of friendship could influence bully–victim outcomes on a number of different levels. Within the context of immediate peer group interactions, friends could serve as defenders or allies against aggressive peers (Hodges et al., 1999). In addition, over longer periods of time, friends might facilitate the development of social reputations that discourage maltreatment by peers (Schwartz et al., 1999).

Friendship is also likely to be a powerful “marker” of child attributes (see Parker & Asher, 1987) that minimize long-term risk for victimization by peers. That is, the influence of friendship on the prediction of victimization could be indirect, occurring as a result of third-variable associations between friendship and other more central, processes. The social skills (e.g., emotion regulation) that are required for the establishment and maintenance of friendship may be associated with resiliency in multiple domains of social functioning. A child who develops such competencies, despite early exposure to a difficult home environment, will be unlikely to emerge as a persistent victim of bullying.

Group Social Acceptance and Friendship as Incremental Predictors

Past researchers have made careful distinctions between dyadic friendship relationships and acceptance by the peer group as a whole. Friendship has been conceptualized as an intimate, supportive relationship between two peers, whereas group acceptance involves the collective attitudes of the peer group toward a particular child (Asher, Parker, & Walker, 1996; Bukowski & Hoza, 1989). There are, however, clear associations between these different relational systems. A child who is well accepted by his peers has numerous opportunities for friendship, whereas a rejected child will have more difficulty establishing such relationships (Bukowski, Pizzamiglio, Newcomb, & Hoza, 1996). Thus, it is not surprising that there is some degree of overlap in the outcomes predicted by dyadic friendship and peer group social acceptance (Ladd & Kochenderfer, 1996).

Because of the conceptual and empirical association between dyadic friendship and acceptance by the peer group as a whole, interpretation of analyses focusing on the buffering influence of friendship can be complex. Friendship might act as a proxy for peer group acceptance without having a unique effect on child outcomes. Accordingly, we conducted hierarchical analyses examining the protective influence of friendship, with the effect of group acceptance controlled.

Aggression and the Moderating Role of Friendship

Although most persistently bullied children are characterized by submissive or nonassertive social behavior (Schwartz et al., 1993), a small subgroup of victimized children displays behavioral tendencies that are more aggressive and hostile in nature (Olweus, 1978; Perry et al., 1988). The distal predictors of peer group maltreatment appear to be different for these two subgroups of victims (Bowers et al., 1994; Rigby, 1992; Schwartz et al., 1997). Aggressive victims often experience early home environments that include exposure to marital violence, harsh punitive discipline, and abuse (Schwartz et al., 1997). For submissive or passive victims, however, factors such as maternal overprotectiveness and negativity may be more relevant (Olweus, 1993). The protective role of friendship may vary systematically as a function of these subgroup differences in the predictors of victimization. In the present study, we examined three-way interactions involving aggression, friendship, and early home environment.

Gender and the Moderating Role of Friendship

A final issue considered was the influence of gender. Gender differences in the topography and function of peer group aggression have been explored in previous investigations (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). However, relatively little is known about differences in the mechanisms of risk and protection for girls and boys. It might be the case that the link between specific aspects of early home environment and later peer group victimization differ as a function of gender. Similarly, friendship could be a more powerful buffering factor for one gender group than the other. Although we did not hypothesize gender differences of this nature, we sought to explore the possibility carefully.

The Present Studies

These research questions were examined in two independent prospective investigations. In the first study, we examined predictive relations between preschool home environment and victimization in the middle years of elementary school, with friendship assessed in the intervening years. In the second study, we examined the relation between kindergarten home environment and third-grade victimization, with friendship again assessed in the intervening years (i.e., first and second grade). In both investigations, we examined the moderating role of early friendships in the prediction of later victimization. We conceptualized victimization as a social process that emerges over time as a product of interactions between multiple early risk and protective factors.

Study 1

Study 1 was completed as part of the Child Development Project (CDP), an ongoing multisite longitudinal investigation of children's social development and adjustment (Pettit et al., 1997). This project has also served as the basis for several past reports on the concurrent and predictive correlates of victimization (e.g., Schwartz et al., 1997; Schwartz, McFadyen-Ketchum, et al., 1998) and on the link between family processes and children's social adjustment (e.g., Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1993). Within the context of the CDP, third- and fourth-grade bully–victim outcomes were predicted from children's preschool home environments, with dyadic friendship assessed in Grades 1–3.

Method

Overview

Two separate cohorts, recruited in consecutive years, are participating in the CDP. Data collection is ongoing and began in the summer before the children entered kindergarten. Assessment of children's social and behavioral adjustment have been obtained on an annual basis. The current study examined predictors of victimization when the first cohort was in the fourth grade (mean age = 9-years-old) and the second cohort was in the third grade (mean age = 8-years-old).

Participant Recruitment and Retention

The initial sample was recruited just prior to kindergarten enrollment in three geographic regions (Bloomington, IN; Knoxville, TN; Nashville, TN). Parents were approached by research staff and asked to participate in a longitudinal study of child development. About 75% of the parents consented.

A total of 585 children (304 boys, 281 girls) participated in the study: 308 in Cohort 1, 277 in Cohort 2. At the time of the victimization assessment, 530 of these children (91%) were retained in the study and assessed by either teachers, mothers, or peers. However, due to difficulties interviewing peers of those participants who had moved to remote sites, we were able to obtain peer nomination data for only 389 of these children. Analyses focusing on a number of indicators of social and behavioral adjustment indicated that these 389 children were representative of the full CDP sample (see Schwartz et al., 1999). The number of children varied across analyses, due to missing values. In the final subsample, approximately 24% of the children were from minority racial or ethnic backgrounds (almost all African American). Most of the children were from lower- to middle-socioeconomic-class backgrounds, with approximately 26% of the children coming from economically disadvantaged families (i.e., families classified in the two lowest socioeconomic status groups, according to criteria specified by Hollingshead, 1979).

Harsh Family Environment

The assessment of family environment is briefly summarized here, but it has been described in greater detail in past reports (e.g., Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994b). In the summer before the child began kindergarten, a trained interviewer visited each child's home to conduct a 150-min interview with the child's mother. Before beginning, the interviewer informed the mother of the range of questions to be asked and the ethical and legal obligation to report any concern of current physical danger to the child. The interview consisted of a comprehensive series of open-ended and structured questions regarding the child's developmental history, socialization, and family background. On the basis of the mothers' responses, the interviewer made a series of 5-point ratings of a number of aspects of the child's preschool environment. Reliability of the ratings was assessed by a second rater, who accompanied the interviewer on the family visit, or by a rater who listened to an audiotape recording of the interview, for 56 randomly selected families (total sample size differs across ratings due to missing values). Separate ratings were made for each of two eras in the child's life: the period from the child's first birthday until 1 year before the interview, and the 1-year period preceding the interview. The analyses presented in this article are based on mean ratings across the eras, a period that we refer to as T1. The ratings of interest in the current report include the following:

Harshness of discipline

A rating of maternal use of restrictive or punitive discipline, with points ranging from nonrestrictive, mostly prosocial to severe, strict, often physical. Independent rater agreement was r = .80 (p ≤ .001), and the correlation between ratings for the two eras was .74 (p ≤ .0001).

Marital conflict

A rating of the degree of conflict between the mother and her husband/partner that was completed only in households in which the mother reported an adult partner who was significantly involved in the childcare. Points ranged from hardly even shout to physical more than once. Independent rater agreement was r = .79 (p ≤ .001), and the correlation between ratings for the two eras was .54 (p ≤ .0001).

Stress

A rating of the level of day-to-day stress experienced by the child's family in terms of major changes or adjustments (e.g., death of family members, divorce, legal difficulties). Points ranged from minimal challenge to severe, frequent challenges. Independent rater agreement was r = .79 (p ≤ .001), and the correlation between ratings for the two eras was .48 (p ≤ .0001).

Abuse

A rating of the probability that the child has experienced physical maltreatment. Points ranged from definitely no harm to possible harm and then to definite harm. If the interviewer rated the probability of maltreatment as at least possible harm in either era, the child was classified as maltreated (0 = not maltreated in either era, 1 = maltreated in at least one era). This assessment of physical abuse has been extensively validated in past reports and found to correlate with relevant demographic factors and child outcomes (Dodge et al., 1994a). Interrater agreement was 90% (κ = .56).

Children for whom current physical abuse was suspected were reported to local child protective service agencies (after the family was informed again of the interviewer's legal and ethical requirement to disclose). Ambiguous cases were discussed with local expert consultants and were resolved through additional probing of parents.

During the full home visit, the interviewer had opportunities to observe the mother and child interact with each other. The interviewer coded these interactions on a postvisit inventory, which included items adapted from the HOME (Home Observation for the Measurement of Environment) scale (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984). A postvisit inventory was also completed independently by a second interviewer who visited the home to assess the child (interviewer agreement was high, as described by Dodge et al., 1994b). A maternal hostility score was derived from this measure on the basis of the occurrence or nonoccurrence of each of the following four behaviors (as coded by either interviewer): “shouts at child,” “otherwise expresses overt hostility or annoyance toward child,” “tells child to behave or pay attention,” and “negative physical contact” (α = .70).

Peer Group Acceptance and Friendship

Peer group acceptance and friendship were assessed each year of the study by means of a peer nomination interview. All peers whose parents consented participated in the interview (consent rates were at least 75% in ail classrooms). The interview was administered individually during the first 3 years of the study, and a group format was used in the later years of the project. Children were given a roster of the other children in their classroom and were asked to identify the three peers they liked most and the three peers they liked least: they were then asked to rate each child in their class on a 1–5 liking rating scale (higher ratings indicated greater liking).

The total number of like and dislike nominations received by each child was calculated and standardized within each classroom. A social preference score, which served as an index of peer group acceptance, was calculated as the standardized difference between the like and dislike scores (as per Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). In addition, children who reciprocally rated each other with the highest possible liking rating (e.g., reciprocal ratings of 5) were classified as friends, and the total number of friendships that each child had was calculated.

Our assessment of friendship differed somewhat from assessments used by previous investigators, who have relied primarily on reciprocated “best friend” (Parker & Asher, 1993) or reciprocated “like most” nominations (e.g., Hodges et al., 1997). The reciprocated nomination approach has been well validated in past research (Asher et al., 1996), although constrained variability can be an issue for estimates generated with limited-choice procedures (e.g., procedures limiting children to three nominations: see Furman, 1996). A potential advantage associated with the reciprocated liking rating index is that the number of friends whom a child can identify is restricted only by the size of the classroom (see George & Hartmann, 1996). This approach also allowed us to use distinct items for estimation of peer group acceptance and friendship (Parker & Asher, 1993). Evidence regarding the concurrent and predictive validity of reciprocated liking ratings has been presented in a past study based on the CDP (Schwartz et al., 1999). Other investigators have also described overlap between reciprocated “best friend” nominations and reciprocated liking ratings (Bukowski, Hoza, & Newcomb, 1994).

For purposes of later analysis, we calculated mean friendship and social preference scores across second and third grade for Cohort 1 participants and across first and second grade for Cohort 2 participants. We refer to this assessment period, which includes the 2 years prior to the assessment of victimization, as T2.

Victimization and Aggression

The peer nomination interview was expanded to include three victimization descriptors (i.e., “gets picked on,” “gets teased,” “gets hit or pushed”) and three aggression descriptors (“starts fights,” “says mean things,” “gets mad easily”) in fourth grade for Cohort 1 participants and in third grade for Cohort 2 participants. Children nominated up to three peers for each item.

For each child, a victimization score was calculated from the total nominations received for the victimization items (α = .82), and an aggression score was calculated from the total nominations received for the aggression items (α = .89). Both scores were standardized within classroom. The reliability and validity of these scores has been extensively documented in past investigations (e.g., Schwartz et al., 1997; Schwartz, McFadyen-Ketchum, et al., 1998). For ease of presentation, we refer to the time at which these data were obtained as T3.

Results

Overview

Our analysis strategy focused on examining T2 friendship as a moderator in the predictive linkages between T1 home environment and T3 victimization. Previous analyses conducted within this data set did not yield any predictor by cohort interactions that approached significance (Schwartz et al., 1997). Accordingly, all analyses were based on the full sample, and cohort was not included as a term in our models. Calculation and interpretation of interaction effects were guided by the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991) and Jaccard, Turrisi, and Wan (1990). Correlations among all variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations Among Predictor, Moderator, and Outcome Variables for Study 1 (N = 338).

| T1 family environment | T2 moderators | T3 social outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. Restrictive discipline | — | .21*** | .40*** | .37*** | .23*** | −.05 | −.22*** | .21*** | .14** |

| 2. Maternal hostility | — | .17** | .01 | .08 | −.03 | −.11* | .15** | .17** | |

| 3. Abuse | — | .31 *** | .24*** | −.14* | −.22*** | .19*** | .25*** | ||

| 4. Marital conflict | — | .38*** | −.06 | −.16** | .14* | .18*** | |||

| 5. Stress | — | −.01 | −.15** | .16** | .17** | ||||

| 6. Friendship | — | .49*** | −.25*** | −.16** | |||||

| 7. Social preference | — | −.45*** | −.40*** | ||||||

| 8. Victimization | — | .35*** | |||||||

| 9. Aggression | — | ||||||||

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered kindergarten, T2 (Time 2) variables in second and third grades for Cohort 1 and first and second grades for Cohort 2, and T3 (Time 3) varibles in fourth grade for Cohort 1 and third grade for Cohort 2. Analyses are presented with gender controlled.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Relations Between Early Harsh Family Environment and Later Peer Group Victimization

There were significant bivariate correlations between each of the T1 predictor variables and T3 victimization, although the effect sizes were generally modest (see Table 1). A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the relation between the combined five T1 home environment variables and T3 victimization. The full model was significant, F(5, 340) = 7.39 p ≤ .0001, with the combined variables accounting for 9.8% of the variance in T3 victimization. T1 restrictive discipline (β = .158, sr2 = .019, p ≤ .01), and T1 abuse (β = .125, sr2 = .012, p ≤ .01) were independently predictive of T3 victimization (where sr2 is the squared semipartial correlation coefficient, the percentage of variance in the outcome accounted for uniquely by the predictor). There were also marginally significant standardized regression parameters for T1 stress (β = .098, sr2 = .008, p ≤ .10) and T1 maternal hostility (β = .086, sr2 = .007, p ≤ .10).

We then conducted a series of analyses to examine gender differences in the predictors of T3 victimization. Separate analyses were conducted for each of the five T1 family environment variables, with T3 victimization predicted from the main effect of gender, the main effect of T1 family environment variable, and the interaction term for T1 family environment variable by gender. These analyses yielded only one significant effect—for T1 maternal hostility by gender (β = .128, sr2 = .016, p ≤ .05). Bivariate correlations conducted separately, for each gender group indicated a positive correlation between T1 maternal hostility and T3 victimization for girls (r = .25; p ≤ .001) and a nonsignificant correlation for boys (r = .05).

Friendship as a Moderator

To examine the moderating role of T2 friendship in the prediction of T3 victimization, we conducted a separate hierarchical regression analysis for each of the five T1 family environment predictor variables. In each analysis, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of the T1 family environment variable and T2 friendship (entered on Step 1) and the interaction between the T1 family environment variable and T2 friendship (entered on Step 2). Significant interaction effects between T1 home environment and T2 friendship were conceptualized as indicators of moderation (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Holmbeck, 1997). As depicted in Table 2, there were significant interaction effects for each of the five T1 family environment variables.1

Table 2. Analyses of the Moderating Role of T2 Friendship in the Prediction of T3 Victimization From T1 Home Environment: Study 1.

| Step1 | Step 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of T2 friendship | Main effect of T1 home environment | T2 Friendship × T1 Home Environment | Full model | |||||

| T1 home environment variable | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | R2 | |

| Restrictive discipline | −.233 | .054*** | .198 | .039*** | −.146 | .021*** | .121*** | |

| Abuse | −.220 | .048*** | .159 | .024*** | −.125 | .014** | .097*** | |

| Marital conflict | −.235 | .055*** | .125 | .016* | −.106 | .011* | .086*** | |

| Stress | −.239 | .057*** | .159 | .025** | −.156 | .024** | .108*** | |

| Maternal hostility | −.238 | .056*** | .142 | .020* | −.101 | .010* | .089*** | |

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered kindergarten, T2 (Time 2) variables in second and third grades for Cohort 1 and first and third grades for Cohort 2, and T3 (Time 3) variables in fourth grade for Cohort 1 and third grade for Cohort 2. sr2 is the squared semipartial correlation coefficient, the percentage of variance accounted for uniquely by the parameter.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

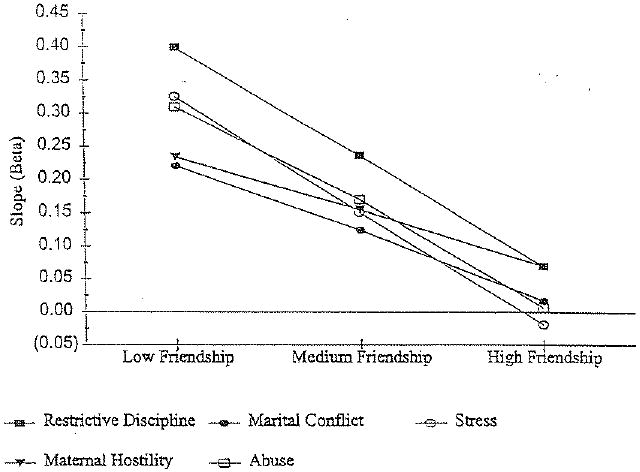

We explored the nature of these effects by specifying models predicting T3 victimization from each of the family environment variables, with T2 friendship fixed at low (1 SD below the mean), medium (the mean), and high (1 SD above the mean) levels. Procedures for conducting such analyses are described by Aiken and West (1991). As shown in Figure 1, the slope of the relation between the T1 home environment variable and T3 victimization consistently declined as the fixed value of friendship increased. The decline in the prediction associated with some of the home environment variables was notable. For example, the relation between T1 restrictive discipline and T3 victimization declined from β = .40 (p ≤ .0001) at low levels of friendship to β = .07 (ns) at high levels of friendship. For each of the home environment variables, the standardized regression parameters were significant at the lowest level of friendship (all ps ≤ .001) but were nonsignificant at the highest level of friendship.

Figure 1.

Changes in the slope of the relation between the T1 (Time 1) home environment variables and T3 (Time 3) victimization at different levels of friendship, assessed with standardized regression parameters. Low friendship was fixed at 1 SD below the mean level of friendship, medium friendship at the mean level of friendship, and high friendship at 1 SD above the mean level of friendship (see Aiken & West, 1991, for details on calculation of these effects). All slopes were significant at low levels of friendship (ps ≤ .001) and nonsignificant at high levels of friendship.

Group Social Acceptance and Friendship as Incremental Predictors

To determine whether the protective influence of friendship occurs independent of the association between group social acceptance and friendship, we conducted a separate hierarchical regression for each of the T1 family environment variables. In each of these analyses, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of the T1 home environment variable, T2 social preference, and T2 friendship (Step 1); and from the two-way interaction terms for T2 Social Preference × T2 Friendship, T1 Home Environment Variable × T2 Social Preference, and T1 Home Environment Variable × T2 Friendship (Step 2). As depicted in Table 3, these analyses yielded significant interaction terms for T1 Stress × T2 Friendship and T1 Abuse × T2 Friendship. There was also a marginally significant term for T1 Marital Conflict × T2 Friendship and T1 Restrictive Discipline × T2 Friendship. In contrast, there were no significant interactions between any of the T1 home environment variables and T2 social preference. Thus, T2 friendship continued to moderate the prediction of T3 victimization associated with some aspects of T1 home environment even after the contribution of T2 social preference was controlled.2

Table 3. Analyses of the Moderating Role of T2 Friendship in the Prediction of T3 Victimization From T1 Home Environment With T2 Social Preference Controlled: Study 1.

| T1 home environment | Step | Effects in model | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictive discipline | 1 | T2 friendship | −.035 | .000 |

| T2 social preference | −.410 | .121*** | ||

| T1 restrictive discipline | .116 | .012* | ||

| 2 | T1 Restrictive Discipline × T2 Social Preference | −.023 | .000 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .099 | .008* | ||

| T1 Restrictive Discipline × T2 Friendship | −.099 | .007† | ||

| Abuse | 1 | T2 friendship | −.022 | .000 |

| T2 social preference | −.422 | .131*** | ||

| T1 abuse | .095 | .009* | ||

| 2 | T1 Abuse × T2 Social Preference | .121 | .008* | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .123 | .012* | ||

| T1 Abuse × T2 Friendship | −.116 | .008* | ||

| Maternal hostility | 1 | T2 friendship | −.030 | .001 |

| T2 social preference | −.427 | .137*** | ||

| T1 maternal hostility | .098 | .010* | ||

| 2 | T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Social Preference | −.018 | .000 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .125 | .014** | ||

| T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Friendship | −.054 | .002 | ||

| Stress | 1 | T2 friendship | −.033 | .001 |

| T2 social preference | −.422 | .131*** | ||

| T1 stress | .097 | .009* | ||

| 2 | T1 Stress × T2 Social Preference | −.022 | .000 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .105 | .009* | ||

| T1 Stress × T2 Friendship | −.111 | .009* | ||

| Marital conflict | 1 | T2 friendship | −.017 | .000 |

| T2 social preference | −.452 | .152*** | ||

| T1 marital conflict | .068 | .004 | ||

| 2 | T1 Marital Conflict × T2 Social Preference | .066 | .003 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .147 | .019** | ||

| T1 Marital Conflict × T2 Friendship | −.095 | .007† |

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered kindergarten, T2 (Time 2) variables in second and third grades for Cohort 1 and first and third grades for Cohort 2, and T3 (Time 3) variables in fourth grade for Cohort 1 and third grade for Cohort 2. sr2 is the squared semipartial correlation coefficient, the percentage of variance accounted for uniquely by the parameter.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Differences in the Moderating Role of Friendship as a Function of Level of Aggression

Next, a series of simultaneous regression analyses was conducted to determine whether the moderating role of T2 friendship differs as a function of a child's level of T3 aggressiveness. A separate analysis was conducted for each home environment variable. In each of these analyses, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of the T1 family environment variable, T2 friendship, and T3 aggression; the two-way interaction terms for T2 Friendship × T3 Aggression, T1 Family Environment Variable × T3 Aggression, and T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship; and the three-way interaction term for T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship × T3 Aggression. Significant three-way interaction terms were conceptualized as an indication of differences in the moderating role of friendship at different levels of aggression. However, these analyses failed to yield any such effects.

Although there were no significant T1 Home Environment × T2 Friendship × T3 Aggression interactions, other findings suggested that the early predictors of T3 victimization differ as a function of level of T3 aggression. Most notably, there was a two-way interaction between T2 friendship and T3 aggression (β = −.123, sr2 = .015, p ≤ .01). Analyses guided by Aiken and West's (1991) recommendations demonstrated that the strength of the negative association between T2 friendship and T3 victimization increased as the level of T3 aggression moved from low (β = .004, ns) to middle (β = −.219, p ≤ .0001) and then to high (β = −.446, p ≤ .0001). Similarly, we found a series of T1 Home Environment × T3 Aggression interaction effects, with the strength of the relation between harsh home environment and victimization increasing as level of aggression increased (described in detail by Schwartz et al., 1997).3

Differences in the Moderating Role of Friendship as a Function of Gender

We conducted a similar series of simultaneous regression analyses to examine gender differences in the moderating role of friendship. For each of the five T1 home environment variables, we conducted an analysis predicting T3 victimization from the main effects of the T1 family environment variable, T2 friendship, and gender; the two-way interaction terms for T2 Friendship × Gender, T1 Family Environment Variable × Gender, and T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship; and the three-way T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship × Gender interaction term. Significant three-way interactions indicated that the moderating role of friendship differed as a function of gender. However, there was only one significant three-way interaction: T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Friendship × Gender (β = −.181 sr2 = .016, p ≤ .01).

To explore the nature of this three-way interaction, we estimated standardized regression parameters for T1 maternal hostility predicting T3 victimization at low, medium, and high values of friendship (as per Aiken & West, 1991), separately for each gender. For boys, none of these analyses yielded an effect that approached significance. For girls, there was a significant standardized effect at low levels of friendship (β = .429, p ≤ .0001), but the effects at medium (β = .115, ns) and high (β = −.198, ns) levels of friendship were not significant.

Discussion

The results of Study 1 were highly consistent with our initial hypotheses. Children who experienced punitive, harsh, stressful, and potentially violent home environments in the preschool years were likely to emerge later as targets of maltreatment by peers. However, the association between these aspects of early home environment and victimization in the peer group was of higher magnitude for children with a low number of friendships than for children with many friendships. These findings complement existing research on the proximal predictors of victimization (e.g., Hodges et al., 1997) by providing evidence that friendship also influences the prediction of victimization from more distal processes (i.e., early home environment).

Interestingly, for some aspects of harsh home environment, the moderating effect of friendship remained significant even after the variance associated with group social acceptance (i.e., social preference) was statistically controlled. Ladd, Kochenderfer, and Coleman (1997) have recently argued that peer group victimization, global acceptance/rejection, and dyadic friendship are distinct relational systems. The current results support this perspective.

The findings with regard to aggression are also of note. Our analyses failed to produce evidence that the role of friendship differs as a function of a child's level of aggressiveness (i.e., we did not find any significant Aggression × Friendship × Home Environment three-way interaction effects). However, harsh home environments were more strongly predictive of later victimization for aggressive than nonaggressive children (see Schwartz et al., 1997). Moreover, we found that the magnitude of the association between friendlessness and victimization increased with increasing levels of aggression. Thus, there are clearly important differences in the predictive pathways for aggressive and nonaggressive victims, but friendship appears to serve as a moderating factor for both subgroups.

Similarly, despite evidence that the form and function of bullying differ for girls and boys (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), we found that friendship serves a protective role for both genders. Small gender differences did emerge for the maternal hostility variable, but the findings were not consistent across the other indicators of early harsh environment. Friendship seems to influence the prediction of peer group victimization for both boys and girls.

These results provide a consistent picture of dyadic friendship as a moderating factor in the pathways to peer victimization. Nonetheless, the specific research questions addressed in this investigation have not been previously examined in any known study, and relevant comparison data are not available. Although there are reasons to have confidence in our initial findings, replication of these results would allow for stronger conclusions.

Study 2

Study 2 was completed as part of the Fast Track project, an ongoing study of the development and prevention of conduct problems (see Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992; Lochman & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995). Within the context of the normative sample of the Fast Track project (see Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999), we examined predictive relations between children's early experiences in the home and peer group victimization in the middle years of elementary school. Of the five family environment variables examined in Study 1, marital conflict was problematic because the Fast Track sample contained a high number of single-parent families. The abuse variable was also problematic because scoring differences led to the classification of very few children as maltreated. Therefore, we focused our analyses on harsh and punitive parenting, maternal hostility, and family stress.

We also considered the influences of gender and aggression. Strong patterns of gender and aggression subgroup differences did not emerge in Study 1. However, maternal hostility was more strongly predictive of victimization for girls than boys. Moreover, friendship was a significant moderator of the linkage between maternal hostility and victimization for girls only. We sought to replicate these specific patterns of findings in Study 2.

Method

Overview

The Fast Track study is a multisite longitudinal project that includes schools that receive intervention, as well as nonintervention “control” schools. Participating schools were identified from four geographic sites: Durham, NC; Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; and rural central PA. The details of this investigation, including recruitment and section criteria, have been extensively described elsewhere (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1992, 1999; Lochman & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995). The participating children have been followed on a continuing basis since kindergarten, with assessments of their functioning and adaptation in multiple domains obtained annually. To be comparable to Study 1, the current investigation examined relations among home environment in the summer prior to first grade (T1; approximate mean age of 6 years), friendship in first and second grades (T2; approximate mean ages of 6–7 years), and victimization by peers in third grade (T3; approximate mean age of 8 years). A summary comparison of the design features of the Fast Track and CDP data sets is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Comparison of Study Design Features for the CDP (Study 1) and Fast Track (Study 2).

| Design feature | CDP (Study 1) | Fast Track (Study 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Samplea | ||

| No. of participants | 389 (198 boys, 191 girls) | 243 (115 boys, 128 girls) |

| Location of participants | Nashville, TN; Knoxville, TN; Bloomington, IN | Nashville, TN; Durham, NC; Seattle, WA; rural central PA |

| Ethnic/racial composition | 76% European American 22% African American 2% “other” |

53% European American 40% African American 7% “other” |

| Socioeconomic backgroundb | 26% economically disadvantaged | 61% economically disadvantaged |

| Predictor variables | ||

| Time of assessment | Summer before kindergarten | Summer before 1st grade |

| Environment measures | Restrictive discipline, maternal hostility, stress, marital conflict, abuse | Restrictive discipline, maternal hostility, stress |

| Methods of assessment | Oral interview, postvisit inventory | Oral interview, postvisit inventory |

| Moderator variables | ||

| Time of assessment | 2nd & 3rd grade for Cohort 1; 1st & 2nd grade for Cohort 2 | 1st & 2nd grade |

| Assessment of friendship | Reciprocated liking ratings (1–5 scale) | Reciprocated liking ratings (1–3 scale) |

| Assessment of social acceptance | Social preference (standardized difference between “like most” and “like least” scores) | Social preference (standardized difference between “like most” and “like least” scores) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Time of assessment | 4th grade for Cohort 1; 3rd grade for Cohort 2 | 3rd grade |

| Assessment of aggression | 3 peer nomination items | 1 peer nomination item |

| Assessment of victimization | 3 peer nomination items | 1 peer nomination item |

Note. CDP = Child Development Project.

Participants in current studies.

Economic disadvantage was defined by classification in one of the two lowest socioeconomic status groups, using criteria specified by Hollingshead (1979).

Participants

The 387 children participating in the current study comprised the Fast Track “normative” sample. All kindergarten children enrolled in the control schools (i.e., nonintervention schools) were rated by their teachers for the presence of behavior problems. At each of the four geographic sites, 10 children from each decile of the teacher rating score distributions were recruited, forming a sample of 100 children at each site. This selection represented the race and sex composition in each decile of the teacher screen. At one site, only 87 children were selected because one of the schools dropped out of the study during the first year. T3 victimization assessments were available for 243 of these children (almost all of the children in the initial sample were retained across the first 3 years of the study, but peer nomination data were not collected for children who had moved out of the Fast Track schools). Across the four sites, 53% of the children were boys, 47% were of minority ethnic/racial background (40% African American, 7% other backgrounds), and 61% were from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (assessed via the Hollingshead, 1979, four-factor method).

Harsh Home Environment

In the summer before the children entered first grade (i.e., T1), trained interviewers visited each child's home to complete a structured interview with the child's mother (a detailed psychometric analysis of the interview was conducted by Miller-Johnson, Maumary-Gremaud, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995). The mothers were asked to respond to a series of open-ended and structured question regarding their child's developmental history, socialization, and family background. On the basis of each mother's responses, the interviewer completed 5-point ratings regarding a number of aspects of the child's home environment. Ratings were completed for two eras in the child's life: the period before the child entered kindergarten and the period after the child entered kindergarten. Analyses presented in this study are based on the preschool era only (the first era) in order to maximize comparability with Study 1. Variables derived from the interview included the following:

Harshness of discipline

As described in Study 1, interviewers rated maternal disciplinary strategies from nonrestrictive, mostly prosocial to severe, strict, often physical. The correlation between ratings across the two eras was .77 (p ≤ .0001).4

Stress

The interviewer read a list of stressful experiences to the mother (e.g., medical problems, divorce, financial problems, legal problems) and asked her to identify events that had occurred and to determine whether the impact of each event on the family was minor or major (0 = did not occur, 1 = minor occurrence, 2 = major occurrence). The total score across all events constituted the child's score for exposure to stress (α = .74).

After completion of the home visit, the interviewers coded behaviors observed during the interview on a postvisit inventory, which was based on the inventory used in Study 1. A maternal hostility score was derived on the basis of the nonoccurrence–occurrence of the following: “mother shouted at child,” “mother expressed anger toward child,” “mother threatened child,” “mother used sarcasm toward child,” “mother hit (grabbed, etc.) child” (α = .62).

Friendship and Group Social Acceptance

In the spring semester of each year of the study, consenting classmates (consent rates were at least 75% in each classroom) of each of the participants were individually administered a peer nomination interview. The interviewer presented the child with a class roster and read the names on the roster aloud to ensure that the child was familiar with his or her classmates. Children were also asked to nominate three liked peers and three disliked peers and to rate each of their peers on a 1–3 liking scale (lower scores indicate greater liking).

Using the procedures described in Study 1, we then calculated friendship and social preference scores for each year of the study. For later analysis, summary T2 scores were calculated from the mean scores across the first and second grades (the 2-year period prior to the assessment of victimization).

Victimization and Aggression

During the administration of the peer nomination interview, the children were read a series of behavioral descriptors and were asked to nominate up to three peers who fit each descriptor. Included was one victimization item (“kids who get picked on or teased by other kids”) and one aggression item (“kids who start fights”). These items were derived from the scales used in Study 1 and have been extensively validated in past studies (Schwartz et al., 1997; Schwartz, McFadyen-Ketchum, et al., 1998). Although only one item was used for each construct, single-item peer nomination assessments are generated on the basis of the responses of multiple raters (i.e., multiple nominating of classmates) and have strong psychometric properties (Coie, Terry, Lenox, Lochman, & Hyman, 1995). For later analysis, victimization and aggression scores were generated by calculating the total number of nominations received for each item, standardized within class.

Results

Overview

Similar to Study 1, analyses focused on the moderating role of T2 friendship in the relation between T1 family environment and T3 victimization. Correlations among the variables are summarized in Table 5. The pattern of effects was generally similar to the pattern observed in Study 1. In contrast to the earlier analyses, however, the stress variable was not strongly associated with other aspects of early family environment.

Table 5. Correlations Among Predictor, Moderator, and Outcome Variables for Study (N = 230).

| T1 home environment | T2 moderators | T3 social adjustment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Restrictive discipline | — | .18* | .18* | −.09 | −.30*** | .24** | .36*** |

| 2. Maternal hostility | — | .09 | −.11 | −.15* | .08 | .09 | |

| 3. Stress | — | −.01 | −.10 | −.01 | −.01 | ||

| 4. Friendship | — | .33* | −.14* | −.09 | |||

| 5. Social preference | — | −.29*** | −.40*** | ||||

| 6. Victim | — | .16* | |||||

| 7. Aggression | — | ||||||

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered first grade, T2 (Time 2) variables in first and second grades, and T3 (Time 3) variables in third grade. Correlations were conducted with gender controlled.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Relations Between Early Harsh Family Environment and Later Peer Group Victimization

A multiple regression analysis was conducted predicting T3 victimization from the three T1 home environment variables. The full model was significant, F(3, 224) = 4.87, p ≤ .005, accounting for 6.13% of the variance in T3 victimization. T1 restrictive discipline (β = .239, sr2 = .052, p ≤ .0005) was independently predictive of victimization.

A series of analyses was then conducted to examine gender differences in the predictors of T3 victimization. A separate analysis was conducted for each of the three T1 family environment predictor variables, with T3 victimization predicted from the main effect of gender, the main effect of the T1 family environment variable, and the interaction between gender and T1 family environment. However these analyses failed to yield any significant interaction effects.

Friendship as a Moderator

To examine the moderating role of friendship in the prediction of victimization, we conducted a separate hierarchical regression analysis for each of the three T1 family environment predictor variables. In each analysis, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of the T1 family environment variable and T2 friendship (entered on Step 1) and the interaction between the T1 family environment variable and T2 friendship (entered on Step 2). As shown in Table 6, there were significant interaction effects for T1 restrictive discipline and T1 maternal hostility.

Table 6. Analyses of the Moderating Role of T2 Friendship in the Prediction of T3 Victimization From T1 Home Environment: Study 2.

| Step1 | Step 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect of T2 friendship | Main effect of T1 home environment | T2 Friendship × T1 Home Environment | Full model | ||||

| T1 home environment variable | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | R2 |

| Restrictive discipline | −.136 | .018* | .226 | .051*** | −.140 | .019* | .095*** |

| Stress | −.156 | .025* | .007 | .000 | .016 | .000 | .025 |

| Maternal hostility | −.149 | .022* | .069 | .005 | −.164 | .020* | .049* |

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered first grade, and T2 (Time 2) variables were collected in first and second grades.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .001.

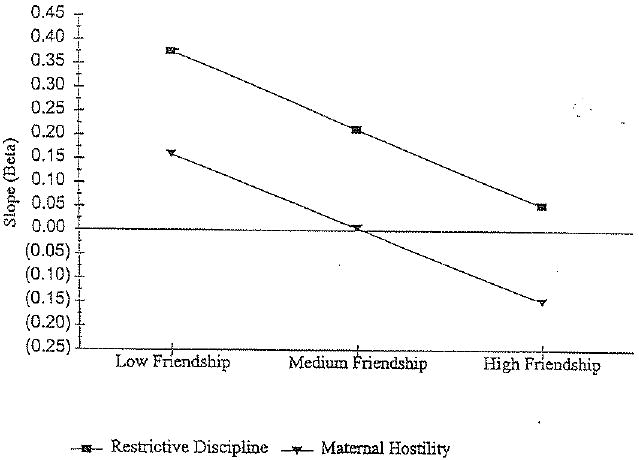

To explore the nature of these effects, we again used the procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) to examine relations between the T1 home environment variables and T3 victimization at low, medium, and high levels of friendship. As shown in Figure 2, the slope of the relation between the T1 home environment variables and T3 victimization consistently declined as the level of T2 friendship increased. At low levels of T2 friendship, the effect was significant for restrictive discipline (p ≤ .001) and marginally significant for maternal hostility (p ≤ .06). In contrast, the effects were nonsignificant at high levels of T2 friendship for both home environment variables (the negative β for maternal hostility at high levels of friendship was not significant and should not be interpreted).

Figure 2.

Changes in the slope of the relation between the T1 (Time 1) home environment variables and T3 (Time 3) victimization at different levels of friendship, assessed with standardized regression parameters. Low friendship was fixed at 1 SD below the mean level of friendship, medium friendship at the mean level of friendship, and high friendship at 1 SD above the mean level of friendship (see Aiken & West, 1991, for details on calculation of these effects). The slope is significant at low levels of friendship (p ≤ .001) for restrictive discipline and marginal for maternal hostility (p ≤ .06). For both home environment variables, the slopes do not approach significance at high levels of friendship.

Social Acceptance and Friendship as Incremental Predictors

To determine whether the protective influence of friendship occurred Independent of group social acceptance, we conducted a separate hierarchical regression for each of the T1 family environment variables for which there was a significant interaction with T2 friendship (i.e., restrictive discipline and maternal hostility). In each analysis, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of the T1 home environment variable, T2 social preference, and T2 friendship (Step 1); and the two-way interaction terms for T2 Social Preference × T2 Friendship, T1 Home Environment Variable × T2 Social Preference, and T1 Home Environment Variable × T2 Friendship (Step 2). As depicted in Table 7, even after T2 social preference had been controlled, there was a significant interaction effect for T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Friendship. In contrast, the interactions with T2 social preference did not approach significance.

Table 7. Analyses of the Moderating Role of T2 Friendship in the Prediction of T3 Victimization From T1 Home Environment With T2 Social Preference Controlled: Study 2.

| T1 home environment variable | Step | Effects in model | β | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictive discipline | 1 | T2 friendship | −.065 | .004 |

| T2 social preference | −.235 | .045* | ||

| T1 restrictive discipline | .163 | .024* | ||

| 2 | T1 Restrictive Discipline × T2 Social Preference | .065 | .003 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .061 | .003 | ||

| T1 Restrictive Discipline × T2 Friendship | −.085 | .006 | ||

| Maternal hostility | 1 | T2 friendship | −.061 | .003 |

| T2 social preference | −.279 | .069*** | ||

| T1 maternal hostility | .039 | .001 | ||

| 2 | T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Social Preference | −.011 | .000 | |

| T2 Friendship × T2 Social Preference | .106 | .001 | ||

| T1 Maternal Hostility × T2 Friendship | −.176 | .022* |

Note. T1 (Time 1) variables were collected in the summer before the children entered first grade, T2 (Time 2) variables in first and second grades, and T3 (Time 3) variables in third grade. Effects were entered simultaneously at each step, and steps were entered sequentially. sr2 is the squared semipartial correlation coefficient, the percentage of variance accounted for uniquely by the parameter.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .001.

Differences in the Moderating Role of Friendship as a Function of Level of Aggression

A series of simultaneous regression analyses was conducted to determine whether the moderating role of T2 friendship differs as a function of a child's level of T3 aggressiveness. A separate analysis was conducted for each home environment variable, predicting T3 victimization from the main effects of the T1 family environment variable, T2 friendship, and T3 aggression; the two-way interaction terms for T2 Friendship × T3 Aggression, T1 Family Environment Variable × T3 Aggression and T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship; and the three-way interaction term for T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship × T3 Aggression. However, these analyses failed to yield any significant three-way interactions.

Differences in the Moderating Role of Friendship as a Function of Level of Gender

Next, we examined gender differences in the moderating role of friendship. A separate simultaneous regression analysis was conducted for each home environment predictor variable. In each analysis, T3 victimization was predicted from the main effects of T1 family environment variable, T2 friendship, and gender; the two-way interaction terms for T2 Friendship × Gender, T1 Family Environment Variable × Gender, and T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship; and the three-way T1 Family Environment Variable × T2 Friendship × Gender Interaction. However, these analyses did not yield any significant three-way interactions.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 were generally consistent with the findings of Study 1. Early exposure to harsh, punitive, and rejecting home environments was associated with later victimization in the peer group, but the predictive linkages between these aspects of home environment and peer group victimization were stronger for children who had few friendships than for children with numerous friendships. Study 2 also replicated our earlier findings with regard to the roles of gender and aggression. The moderating effect of friendship did not differ as a function of gender or of children's level of aggressiveness. Although it has been argued in the past that gender and aggression are factors that can exert a powerful influence on the predictors of victimization (see Schwartz et al., 1997, 1999), the interactive processes examined here appear to be relatively invariant across groups (it should be emphasized that a finding of “no differences” does not provide a strong basis for conclusion).

General Discussion

Taken together, the findings of Study 1 and Study 2 provide consistent support for conceptualizations of friendship as a moderator in the pathways to victimization. In both investigations, the examined risk factors were not predictive of victimization for children who had numerous friendships. In contrast, there were moderately strong associations between early exposure to harsh home environment and later victimization by peers for children who did not succeed in establishing friendships. These effects remained constant across gender, and across levels of aggression.

The replication of findings in two distinct samples is particularly compelling when considered in light of the low power that characterizes analyses of moderator effects in quasi-experimental research designs (McClelland & Judd, 1993). Analyses conducted across samples also provide some assurance that spurious interaction effects did not emerge as result of the distributional properties of the predictor variables (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998). Rigorous statistical procedures can minimize the possibility of such interpretational difficulties, but replication still provides the strongest foundation for conclusions (Rutter, 1983).

Past research on the determinants of peer group victimization has tended to emphasize main effect relations between particular risk factors and victimization (e.g., Schwartz et al., 1993). The current results, and the recent findings of other investigators (e.g., Egan & Perry, 1998; Hodges et al., 1997; Ladd et al., 1997), are more consistent with an interactive model of risk. Early negative experiences in the home can leave a child vulnerable to victimization by peers, but external factors such as friendship may alter the relevant developmental trajectories.

Identification of the Underlying Mechanisms

Although our findings highlight the developmental significance of friendship, the mechanisms through which these dyadic relationships exert an influence on the prediction of victimization are not yet clear. We have hypothesized that friendship mitigates the influence of risk factors (i.e., exposure to a difficult home environment) by serving an ameliorative function. As past investigators have suggested, friendships could play a critical role in facilitating the development of social competence, self-esteem, and school adjustment (Berndt, 1996; Hartup, 1996; Ladd, 1990). Interactions with friends could also offer opportunities for the development of social skills and regulatory capacities that help children to compensate for deficits that they bring to their early peer group interactions (Price, 1996). Thus, children who are exposed to harsh home environments may be likely to display behavior deficits (e.g., emotion dysregulation) that are predictive of victimization by peers (Schwartz et al., 1997). However, these problematic developmental trajectories can be altered by the positive influence of early friendships.

An important task for future researchers will be direct investigation of the impact of friendship on specific vulnerability factors. Research examining the effects of participation in friendship on children's emerging abilities to regulate behavior and emotion might prove particularly informative. Impairments in these domains are likely to play a key role in determining bully–victim outcomes and may serve as mediating processes linking early harsh home environments to later maltreatment by peers (Schwartz et al., 1997).

A somewhat different perspective on these findings can be derived from the existing research on friendship and peer victimization. Hodges et al. (1997, 1999) have argued that friends serve an important protective role in bully–victim interactions. These investigators have hypothesized that friends can reduce the likelihood that a child will emerge as a victim by offering support against potential aggressors. Although particular behavioral or psychological attributes might increase risk for victimization (Egan & Perry, 1998; Schwartz et al., 1993) children are unlikely to target peers who are defended by numerous friends. The social support associated with early friendships could also influence the development of social reputations that minimize later risk for victimization (see Schwartz et al., 1999).

Another possibility is that friendship does not have a direct influence on the pathways to victimization but, instead, is a “marker” of child attributes that minimize risk for negative social outcomes (Parker & Asher, 1987). Successful formation and maintenance of friendship requires complex social skills. These skills could also have relevance for peer victimization, which has been conceptualized as a dyadic phenomenon by some researchers (e.g., Dodge, Price, Coie, & Christopoulos, 1990). For example, the capacity to modulate negative emotional states during dyadic interactions is central to both friendship (Parker & Gottman, 1989) and successful defense against potential victimizers (Schwartz, Dodge, et al., 1998). Children who have numerous friends may have developed interactive styles that discourage maltreatment by peers, even though these children may also exhibit other psychological or behavioral vulnerabilities.

A conceptualization of friendship as a marker of resiliency provides a parsimonious explanation for our findings. This perspective is particularly compelling when considered in light of our limited understanding of the casual mechanisms underlying the moderating effect of friendship. Remaining to be explored, however, are the relevant child attributes that are both associated with friendship and predictive of resiliency. These qualities are likely to be distinct from the more global social competencies that are typically associated with popularity or consensual acceptance by peers (see Parker & Seal, 1996). In our analyses, friendship maintained a moderating role even after the interaction between group social acceptance (i.e., social preference) and harsh home environment was statistically controlled.

The Process of Friendship

A related set of questions focuses on the specific conditions under which friendship is likely to have a beneficial impact. For example, it may be the case that different kinds of friends influence bully–victim outcomes in different ways. Friends that are socially skilled, well liked by their peers, and high in self-esteem could have a different influence than friends who are less well adjusted. Consistent with this suggestion, Hodges et al. (1997) found that the moderating influence of friendship on the prediction of victimization varied as a function of the behavioral attributes of a child's friends. Within the larger literature on friendship, there is also evidence that the characteristics of a child's friends can have significant repercussions for that child's social development (see Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995).

Similarly, friendship quality is likely to be an important factor. Researchers have viewed the phenomenon of friendship from multiple levels, considering both the number of friends that a child has and the specific quality of a child's friendships (Bukowski & Hoza, 1989; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1996). Findings from this work indicate that friendship has both negative and positive features (Berndt, 1986). Some positive features of friendship include closeness, intimate exchange, support, and companionship, whereas negative features might include conflict, rivalry, and jealousy. Not surprisingly, the positive aspects of these relationships have been most closely linked to desirable psychosocial outcomes (Berndt, 1996). Friendships that are high in such features may be particularly likely to serve an ameliorative role in the developmental pathways examined in this investigation.

It is also unclear whether the influence of friendship on bully–victim outcomes should be conceptualized in continuous or non-continuous terms. An implicit assumption underlying the current research is that potential benefits of friendship increase in a linear fashion as the density of a child's network of friendships increase. Accordingly, the moderating factor that we focused on was children's total number of friendships across the early years of elementary school. However, the developmental impact of friendship can also be conceptualized in “all-or-none” terms, with the central comparison being between children who have at least one friend and children who do not have any friends (see Bukowski & Hoza, 1989). From this perspective, the effects of friendship are not viewed as cumulative across multiple relationships, and a child who has only one friend is expected to derive the same developmental benefit as a child who has several friends. A nonlinear model might prove particularly useful for research focusing on high-quality friendships that are stable over long periods of time (Parker & Seal, 1996).

Other Caveats

Several other caveats should be kept in mind when considering our findings. Overall, the pattern of findings was highly consistent across Study 1 and Study 2, but there were some discrepancies. In Study 1, we found a relation between early exposure to major stressors in the home and later peer group victimization. This linkage was, in turn, moderated by friendship. In Study 2, however, stress was not a significant predictor of victimization, nor was the relation between stress and victimization influenced by children's friendships. We suspect that this inconsistency reflect differences in methods of assessing stress across the two studies. Stress was concurrently correlated with other indicators of disruptive home environment in Study 1, but a similar pattern of correlations did not emerge in Study 2. Nevertheless, in the absence of replication, we avoid strong inferences regarding stress and victimization.

In addition, we were unable to replicate the findings of Study 1 with regard to gender differences in the prediction of peer group victimization. Our Study 1 analyses suggested that maternal hostility is a stronger predictor of victimization for girls than boys. In Study 2, however, the predictors of victimization did not differ for boys and girls (although concerns regarding difficulties detecting moderator effects should be considered; see McClelland & Judd, 1993). Further research could prove informative, but the current findings are not suggestive of a strong pattern of gender differences in the distal predictors of victimization.

It is also important to recognize that the correlational nature of this research precludes causal conclusions regarding the relation between family environment and victimization in the peer group. Because these studies used prospective designs, we can make statements regarding statistical associations between early experiences in the home and later peer victimization. We can also identify factors, such as friendship, that moderate the predictive linkage between early home environment and later victimization. However, the possibility still exists that third variables determine both family experience and peer group outcomes. Furthermore, our findings do not provide a strong foundation for inferences regarding the relative contributions of biological and socialization processes.

Another potential concern is that these findings might not generalize across different ethnic/racial or cultural groups. The investigations reported here included samples of diverse ethnic composition. However, we chose not to examine ethnic/racial group differences in the predictors of peer victimization. Our ability to make conclusions regarding such differences would have been quite limited given the likely influence of more immediate contextual factors (i.e., classroom ethnic composition) on the distribution of victimization in the peer group (Smith & Sharp, 1994). Nonetheless, there is an emerging body of research focusing on ethnic/racial group differences in the impact of negative experiences in the home (e.g., Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Pettit et al., 1997). This research might have significant implications for our understanding of the determinants of victimization.

A final set of concerns focuses on our assessment of friendship. Past investigators have argued that children have a very specific conceptualization of friendship, so that items that directly ask children about friendship are necessary (e.g., mutual “best friend” nominations; see Asher et al., 1996). Other investigators have focused more on the issue of reciprocity of high positive regard and have viewed items that assess mutual liking as acceptable assessments of friendship (e.g., reciprocated “like most” nominations, reciprocated liking ratings; Bukowski & Hoza, 1989; Bukowski et al., 1994). The reciprocal liking ratings procedure used in the current investigation is conceptually consistent with this later perspective. However, items that directly assess friendship (e.g., Gauze et al., 1996; Parker & Seal, 1996) would seem to have greater face validity than items that tap the more general construct of liking (Asher et al., 1996) and, for that reason, may represent a more optimal assessment strategy.

Our approach of using reciprocated liking ratings to assess friendship also differs somewhat from the friendship assessments used by past bully–victim researchers, who have relied primarily on reciprocated “like most” nominations (e.g., Hodges & Perry, 1999). We chose to use reciprocated ratings in order to take advantage of the potential gains in validity associated with an unlimited-choice procedure. With the reciprocal ratings approach, the number of peers whom a child can identify as “friends” (i.e., highly liked) is constrained only by the total number of children in his or her classroom. In contrast, the reciprocated nominations approach relies on a limited-choice procedure. That is, the number of peers whom a child can identify as friends (i.e., liked most) is constrained by the maximum number of nominations that the child is allowed to make (typically three nominations). In past work, we have found that unlimited-choice procedures yield friendship estimates that are distributed with greater variability than estimates obtained via limited choice (see Schwartz et al., 1999). It should be noted, however, that findings from factor analytic research suggest that reciprocated nominations and reciprocated ratings are products of the same underlying latent construct of friendship (Bukowski et al., 1994).

In summary, this report has demonstrated the importance of interactive models of risk for understanding the developmental pathways to peer group victimization. The relation between distal risk factors and victimization is complex and influenced by moderating processes. Friendship, in particular, may serve an important function in these developmental pathways. Research on the role of friendship in bully–victim interactions can greatly enhance current understanding of the processes underlying peer victimization.

Acknowledgments

Study 1 (Child Development Project) was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant 42498 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD3052. Study 2 (Fast Track) was supported by NIMH Grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, and R18 MH50953. Fast Track has also been supported by the Center of Substance Abuse Prevention through a memorandum of agreement with NIMH and by Department of Education Grant S184U30002 and NIMH Grants K05MH00797 and K05MH01027. Parts of this article were written while David Schwartz was a summer scholar at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences Stanford, California.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Antonius Cillessen, Dorothy Espelage, Robert Laird. Michael Criss, and Laura Proctor.

Footnotes

Editor's Note. Steven Asher served as the action editor for this article.—JLD

T2 friendship was treated as the moderator variable instead of T3 friendship, because our hypotheses focused on the role of early friendship in the prediction of later victimization. However, for exploratory purposes, we specified a series of models predicting T3 victimization from the main effect of T1 home environment (separate analyses were conducted for each of the five home environment variables), the main effect of T3 friendship, and the interaction between T1 home environment and T3 friendship. The overall pattern of results was similar to the analyses conducted with T2 friendship. There were significant interaction effects for T1 Restrictive Discipline × T3 Friendship (β = −.147, sr2 = .021, p ≤ .005), T1 Stress × T3 Friendship (β = −.116, sr2 = .013, p ≤ .05), T1 Abuse × T3 Friendship (β = −.199, sr2 = .033, p ≤ .0005), T1 Maternal Hostility × T3 Friendship (β = −.108, sr2 = .011. p ≤ .05), and T1 Marital Conflict × T3 Friendship (β = −.156, sr2 = .024, p ≤ .0005). Thus, the relation between early home environment and victimization appears to be moderated by a child's total number of friendships, assessed both concurrently and in the earlier years of elementary school. We also conducted exploratory analyses using a friendship variable derived from reciprocated “like most” nominations at T3 (instead of reciprocated liking ratings). These analyses yielded a significant interaction effect for maternal hostility (β = −.137, sr2 = .016, p ≤ .005) and a tread toward interaction for stress (β = −.079, sr2 = .006, p ≤ .10). For the remaining variables, there were nonsignificant interactions in the expected direction. Because the variability in the reciprocated nomination variable was somewhat restricted in CDP data set (for T3 reciprocated nominations, M = 1. 03. SD = 0. 95), our ability to detect such interactions may have been limited.