Abstract

Background

We previously reported the feasibility of acute orally delivered newly developed conjugated form of human BNP (hBNP) in normal animals. The objective of the current study was to extend our findings and to define the chronic actions of an advanced oral conjugated hBNP (hBNP-054) administered for 6 days upon sodium excretion, and blood pressure. Secondly, we also sought to establish the ability of this new conjugate to acutely activate cGMP and reduce blood pressure in an experimental model of angiotensin II (ANGII)-mediated hypertension (HTN).

Methods and Results

First, we developed additional novel conjugated forms of oral hBNP that were superior to our previously reported hBNP-021 in reducing blood pressure in 6 normal dogs. We then tested the new conjugate hBNP-054 chronically in 2 normal dogs to assess its biological actions as a blood pressure lowering agent and as a natriuretic factor. Secondly, we investigated the effects of acute oral hBNP-054 or vehicle in 6 dogs that received continuous infusion of ANG II to induce hypertension. After baseline (BL) determination of mean blood pressure (MAP) and blood collection for plasma hBNP and cGMP, all dogs received continuous ANG II infusion (20 ng/kg/min, 1 ml/min) for 4 hrs. After 30 min of ANG II, dogs received oral hBNP-054 (400 μg/kg) or vehicle in a random crossover fashion with a one-week interval between dosing. Blood sampling and MAP measurements were repeated 30 min after ANG II administration and 10, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 min after oral administration of hBNP-054 or vehicle.

In the chronic study in normal dogs, oral hBNP-054 effectively reduced MAP for 6 days and induced a significant increase in 24-hr sodium excretion. hBNP was not present in the plasma at BL in any dogs, and it was not detected at any time in the vehicle group. However, hBNP was detected throughout the duration of the study after oral hBNP-054 with a peak concentration at 30 min of 1060±818 pg/ml. In the acute study after ANG II administration, plasma cGMP was not activated after vehicle, while it was significantly increased after oral hBNP-054 (p=0.01 between two groups). Importantly, MAP was significantly increased after ANG II throughout the acute study protocol. However, while no changes occurred in MAP after vehicle administration, oral hBNP-054 reduced MAP for over 2 hrs (from 138±1 after ANG II to 124±2 at 30 minutes, 124±2 and 130±5 mmHg 1 and 2 hrs after oral hBNP-054 respectively; p<0.001).

Conclusions

This study reports for the first time that a novel conjugated oral hBNP possesses blood pressure lowering and natriuretic actions over a 6-day period in normal dogs. Furthermore, hBNP-054 activates cGMP and reduces MAP in a model of acute HTN. These findings advance the concept that orally administered chronic BNP is a potential therapeutic strategy for cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension.

Keywords: conjugated human brain natriuretic peptide; 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP); blood pressure

INTRODUCTION

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is an endogenous peptide produced under physiological and pathological conditions by the heart as a non-active 108 amino acid prohormone 1-3. BNP is cleaved and activated into its 32 amino acid mature form by the trans-membrane enzymes corin and furin 4-6 and possesses natriuretic, diuretic, vasorelaxant, lusitropic, anti-aldosterone properties and direct as well as indirect anti-fibrotic actions 7,8 that could mediate cardiorenal protection in cardiovascular diseases 9,10. While approved as an intravenous agent for heart failure, hypertension may equally be a logical therapeutic target, as its phenotype is elevated blood pressure, often vasoconstriction, diastolic dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis together with impaired pressure natriuresis in the kidney. Moreover, both experimental and human studies demonstrate a lack of activation of BNP in the early stages of HTN that could be viewed as a relative BNP deficiency 11. Indeed, the phenotype of mice lacking the receptor to which BNP binds is characterized by hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis and sudden death 12,13 14.

Despite the specificity and efficacy of peptides that make them desirable as drugs, oral administration of peptides has been a longstanding therapeutic challenge that has limited the development of chronic protein therapy and largely relegated them to parenteral delivery. Recently, however, new technologies have been developed that make this aim achievable. Indeed, we previously reported the acute actions of subcutaneous (SQ) and orally administered conjugated human BNP (hBNP) in normal conscious dogs 9. In those studies, conjugated hBNP (hBNP-021) was absorbed and present in the plasma after SQ and oral administration. More importantly, acute SQ and oral conjugated BNP activated 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), the second messenger of BNP, that implied a maintained structure of the conjugate which retained the intrinsic ability to bind and activate the natriuretic peptide receptor type-A (NPR-A) resulting in a significant reduction of mean arterial pressure (MAP). This previous study was the first demonstration of an oral BNP molecule or derivative that was absorbed intact and promoted biological actions. These encouraging data support the importance of pursuing further studies with oral administration of conjugated forms of human BNP for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases especially hypertension.

Continued work has led to the discovery of two new conjugates (hBNP-050 and hBNP-054) that show greater oral efficacy than did the original hBNP-021. As with the original molecule, these derivatives were intended to improve the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of the peptide to enable oral administration. In vitro activity studies had demonstrated the importance of conjugating at lysine 3 of hBNP 15, so these two conjugates incorporate this key feature.

The first aim was to extend our previous report and to characterize for the first time in normal canines the action of 6 days of oral hBNP on MAP and sodium excretion after identifying the most optimal conjugated hBNP chemical entity. Our second aim was to demonstrate that acute oral administration of conjugated hBNP-054 would result in an increase in plasma levels of hBNP and cGMP, together with a reduction in MAP in a model of acute angiotensin II (ANG II)-induced HTN.

METHODS

The present study was performed in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and approved by the Mayo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Synthesis of conjugated hBNP

Two new hBNP mono-conjugates, hBNP-050, and hBNP-054, were prepared by regioselective attachment of branched, amphiphilic PEG oligomer to the lysine3 of hBNP. The syntheses of the mono-dispersed oligomers as well as the conditions for conjugation have been previously described 15,16. The resultant conjugates were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex; C18, 1.0 cm. i.d. × 25 cm. length) using a gradient system (A: H2O with 0.1% TFA; B: acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA; %B: 25 - 75 over 120 min).

Specifically, over fifty conjugates were prepared by rational design and synthesis and were subjected to various screens. One of the more promising conjugates of BNP, hBNP-050, was tested in a crossover comparison against hBNP-021, which we previously demonstrated to be efficacious in reducing MAP in normal dogs 9. After comparison, hBNP-050 was superior to hBNP-021 in reducing MAP in 6 conscious normal dogs. Another of the more promising candidates, hBNP-054, resulted in similar blood pressure properties compared to hBNP-050. The conjugate hBNP-054 was selected for the oral in vivo study in normal and hypertensive dogs due to its comparatively facile synthesis.

Study Protocol

Normal adult male mongrel dogs (15-20 kg) were used in these studies. Prior to experiments, an arterial port was placed in the femoral artery as previously reported17. Dogs were fed a fixed sodium diet of 100 mEq/day for 5 days prior to initiation of studies with ad lib. access to water and acclimated to standing calm in a sling. On the day of the experiment, the dogs were fasted and placed in a sling in a quiet room for 30 minutes before the beginning of the experiment.

First, we designed a randomized study where hBNP-054 (n=5; 350 μg/kg), native hBNP (n=6; 350 μg/kg), or vehicle (n=6) were administered orally in normal dogs (hBNP-054 was administered to only 5 dogs due to limited supply of conjugated human BNP). Baseline measurements of MAP and blood sampling for hBNP and cGMP were made. MAP and blood samplings were repeated at 10, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240 minutes after oral administration. We then continued in a proof of concept study in 2 of the normal dogs daily oral administration of 350 μg/kg of hBNP-054 was administered once a day for 6 days. On the seventh day vehicle was administered to the two dogs instead of the active hBNP-054. Blood pressure was measured daily before (baseline) and at 10, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 minutes after oral administration of BNP-054 on each day for the 6 consecutive days. Blood pressure was also measured the seventh day before and after oral administration of vehicle. A 24-hour urine collection was performed for 8 days starting the day before oral hBNP-054 administration, and continued for the 6 days of oral hBNP-054 administration, and concluded on day 7 when vehicle was administered instead of active drug.

Finally, we investigated in a randomized crossover-designed study the effects of oral hBNP-054 or vehicle in 6 dogs that received concomitant continuous intravenous infusion of ANG II to induce acute hypertension. After baseline determination of MAP and blood collection for plasma hBNP and cGMP, all 6 dogs received continuous ANG II infusion (20 ng/kg/min, 1 ml/min) for over 4 hrs. After 30 min of ANG II administration, all dogs received oral hBNP-054 (400 μg/kg) or vehicle in a random crossover fashion (one week of interval). Blood sampling and MAP measurements were repeated 30 min after ANG II administration and 10, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 minutes after oral administration of hBNP-054 or vehicle.

Hormone Analysis

Plasma hBNP and cGMP were assessed by radioimmunoassay as previously described 18,19.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± SEM. For the acute studies, data were assessed by one-way ANOVA for comparisons within groups followed by post hoc Bonferroni test. Two-way ANOVA repeated measurements was used for comparisons between groups followed by Bonferroni posttest. The Student unpaired t test was performed for single comparison between groups (GraphPad Prism software 4.0). Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05. Specifically, for the crossover comparative study, the within-treatment analyses of effect over time were done using one-way ANOVA for repeated measures to test the global time effects, with the time contrasts (each post-baseline time versus baseline) as the effects of interest being tested by a post-hoc Bonferroni test when the global test was significant. For the treatment comparison (active versus vehicle), a 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures was performed, with the treatment main effect being tested as the numerator mean square and the treatment * dog interaction mean square as the denominator mean square. This is equivalent to a paired t-test on the average values of each parameter between the 2 treatment periods, with the dog as the observation. Treatment contrasts at specific time points were then tested using the Bonferroni correction.

Finally, in the 2-dog chronic administration study, the study was too small to make inferences to the population of dogs. Instead, to test whether the drug had a reproducible effect in the 2 dogs in the study, analysis was conducted as follows. For the analysis of drug effect on MAP, the null hypothesis of no blood pressure reduction associated with oral BNP was tested by calculating the average MAP following drug administration within the first 2 hours (10 minutes, 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 120 minutes) on each day for each dog. For each dog, the 6 daily post-drug averages were compared to the pre-drug baseline, using a paired t-test with 5 degrees of freedom. The resulting one-sided p-values were combined across the 2 dogs by the Fisher method of combining independent p-values 20. For the analysis of drug effect on 24-hour sodium excretion, the 6 values for the days on drug were compared to the 2 values for days off drug by a 2-sample t-test for each dog, and the resulting 1-sided p-values were similarly combined 20 .

RESULTS

Comparisons between previous and new forms of conjugated hBNP in normal dogs

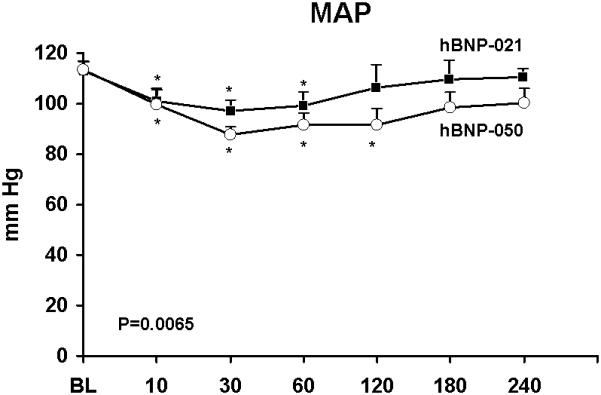

The novel conjugate hBNP-050 resulted in more potent blood pressure lowering effect as compared to the previously reported conjugated hBNP-021 when administered orally in normal dogs (Figure 1). A structurally similar compound (hBNP-054; Figure 2) possessed similar blood pressure lowering actions in normal dogs (Table 1). Due to advantages in synthesis, hBNP-054 was used in the remainder of the studies.

Figure 1.

Acute oral administration of conjugated human BNP-050 (hBNP-050) (open circles) and hBNP-021 (solid squares) in 6 normal conscious dogs. Columns represent mean ± SEM. Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.0065 between hBNP-050 and hBNP-021 groups by two-way ANOVA.

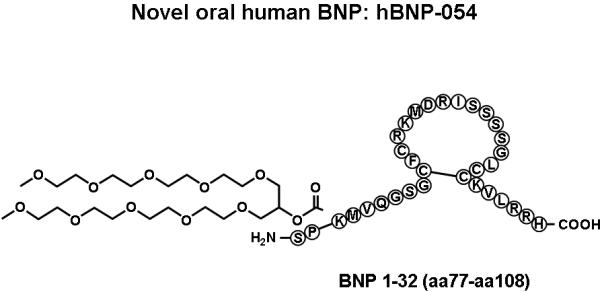

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of conjugates human BNP-054.

Table 1.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) after administration of hBNP-050 (n=6) and hBNP-054 (n=5) in normal dogs

| BL | 10 min | 30 min | 60 min | 120 min | 180 min | 240 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hBNP-050 | 113±3 | 99±6* | 87±3* | 92±5* | 92±6* | 98±6* | 100±6† |

| hBNP-054 | 120±1 | 115±4† | 96±8† | 95±7† | 91±7* | 92±10* | 94±10† |

MAP (mm Hg) ± SEM.

p<0.01

p<0.05 vs baseline (BL)

Acute studies with hBNP-054 in conscious normal dogs

Conjugated hBNP-054 was administered orally in normal dogs and compared to native hBNP and to vehicle. Figures 3A, 3B and 3C illustrate the humoral and blood pressure responses to orally administered hBNP-054, native hBNP, and vehicle in normal conscious dogs.

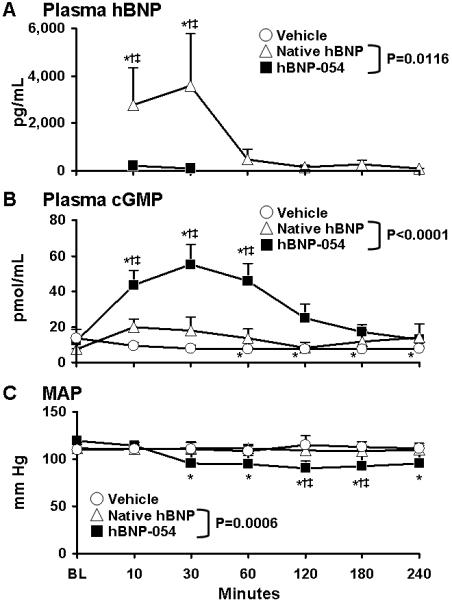

Figure 3.

Acute oral administration of conjugated human BNP-054 (hBNP-054) (solid squares), native hBNP (open triangles), and vehicle (open circles) in normal conscious dogs. Columns represent mean ± SEM.

A) Plasma human Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.0116 between hBNP-054 and native hBNP by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.05 vs vehicle, ‡p<0.05 vs native hBNP two-way ANOVA Bonferroni posttest.

B) Plasma 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P<0.0001 between hBNP-054 and native hBNP by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.05 vs vehicle, ‡p<0.05 vs native hBNP two-way ANOVA Bonferroni posttest.

C) Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.0006 between hBNP-054 and native hBNP groups by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.05 vs vehicle, ‡p<0.05 vs native hBNP two-way ANOVA Bonferroni posttest.

Plasma hBNP was not detectable in the dogs at BL or after vehicle. After oral administration of hBNP-054 and native hBNP, plasma hBNP was detected throughout the time course of the study. Specifically, plasma hBNP was significantly higher after 10 minutes of hBNP-054 (6489±3956 pg/mL) as compared to BL (p<0.05), native hBNP (p<0.05), and vehicle (p<0.05). During the study, plasma hBNP was significantly higher after hBNP-054 compared to native hBNP administration (p=0.0116 between groups) (Figure 3A).

Plasma cGMP significantly increased for 60 minutes after dosing of hBNP-054 (from BL 12.4±1 to 46.3±8 after 10 min, to 55.6±10 after 30 min, to 45.5±9 after 60 min, pmol/mL, p<0.05), while it was significantly reduced after vehicle (from BL 13.9±2 to 7.7±1 after 60 min, to 7.9±2 after 120, to 7.6±1 after 180 min, to 7.7±2 after 240 min, p<0.05). By comparison, cGMP levels were not statistically different from baseline levels after native hBNP administration and overall cGMP level were greater after hBNP-054 as compared to native hBNP and vehicle (p<0.0001 between hBNP-054 and the other groups) (Figure 3B).

MAP decreased at 30 minutes and remained decreased through 240 minutes after hBNP-054 administration (from BL 120±1 to 115±4 after 10 min, to 96±8 after 30 min, to 95±7 after 60 min, to 91.2±7 after 120 min, to 92.4±10 after 180 min, to 93.8±10 mm Hg after 240 min). In contrast, MAP did not change after native hBNP or vehicle administration throughout the study (p=0.0006 between groups) (Figure 3C).

Chronic studies with hBNP-054 in conscious normal dogs

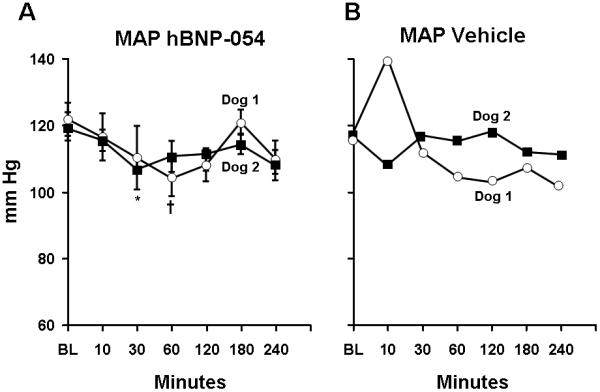

We furthered our observation in normal dogs in which hBNP-054 was administered chronically for 6 days followed by vehicle on the seventh day. Blood pressure was measured before and after oral administration of hBNP-054 or vehicle for 4 hours. Each time hBNP-054 was administered, we observed a significant reduction in MAP. Figure 4A illustrates the average MAP for all 6 days of orally administered hBNP-054. Of note, on the seventh day MAP was not reduced after administration of vehicle (Figure 4B). When the 4 post-infusion MAP values were averaged and compared to the baseline MAP value for each of six days, the resulting paired t-tests produced 1-sided p-values of 0.01125 and 0.0188, which when combined using the Fisher method gave a 1-sided p-value of 0.002, or a 2-sided value of 0.004, indicating evidence that MAP was significantly lowered in these 2 dogs.

Figure 4.

Trend-lines represent average for each dog of mean arterial pressure (MAP) measurements over 6 days of BNP-054 (Figure A) and the corresponding values on day 7 (vehicle) (Figure B). Values indicate MAP ± SEM.

A) Average MAP for each dog over 6 consecutive days, before and after hBNP-054. Baseline (BL), prior to oral administration of hBNP-054. P= 0.0424 and P=0.0399 one-way ANOVA for Dog 1 and Dog 2 respectively. †p<0.05 Dog 1vs BL, and *p<0.01 Dog 2 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. There was no difference between Dogs in responding to hBNP-054 over 6-day period by two-way ANOVA.

B) MAP for each dog on day 7 before (open squares) and after vehicle (open triangles). Baseline (BL), prior to oral administration of Vehicle.

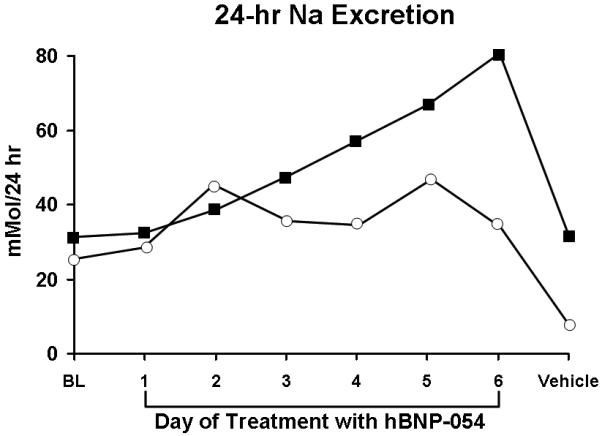

Of note, 24 hours sodium excretion increased every day during chronic oral hBNP-054 as compared to the day before hBNP-054 was initiated, being significantly elevated on day 5 and 6 with oral hBNP-054 administration as compared to the day before commencement of conjugate therapy (p<0.05). Importantly, 24 hour sodium excretion markedly decreased the day of vehicle administration (day 7) returning to baseline levels (Figure 5). When the 6 days with drug were compared to the 2 days (baseline and day 7) off drug using a two-sample t-test for each dog, the resulting 1-sided p-values were 0.0909 and 0.0272, respectively, and when combined using the Fisher procedure, gave a 1-sided p-value of 0.018, or a 2-sided value of 0.036, indicating significant evidence that urinary sodium excretion was increased in these 2 dogs by administration of the drug.

Figure 5.

Trend-line the daily Na excretion for each dog the day before treatment was started (BL), the days (day1 to day 6) of treatment with hBNP-054, and the day of vehicle. The 6 values for the days on drug were compared to 2 values for days off drug by a 2-sample t-test for each dog, and the resulting 1-sided p-values combined as described in the methods.

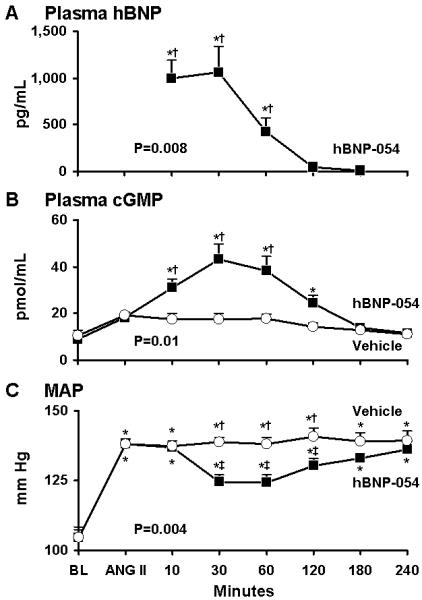

Acute studies with hBNP-054 in conscious hypertensive dogs

In a second phase of the current study, we tested the hypothesis that oral hBNP-054 is efficacious in reducing MAP in a model of acute hypertension induced by ANG II. Here we administered oral hBNP-054 or vehicle in dogs that received concomitant continuous intravenous infusion of ANG II to induce acute HTN.

As expected, hBNP was not present in the plasma at BL in any dogs, and it was not detected in the vehicle group. However, hBNP was detected throughout the duration of the study after oral hBNP-054 with peak concentrations at 10, 30, and 60 min (841±300; 1122±303; and 1060±818 pg/ml respectively) as compared to BL (p<0.05), and vehicle (p<0.05). During the time course of the study, plasma hBNP was overall significantly higher after hBNP-054 compared to vehicle (p=0.008) (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Acute oral administration of conjugated human BNP (hBNP-054) (solid squares), or vehicle (open circles) in 6 conscious dogs after continuous intravenous infusion of angiotensin II (ANG II). Columns represent mean ± SEM.

A) Plasma human Brain Natriuretic Peptide (hBNP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.008 between hBNP-054 and vehicle by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.01 vs vehicle Bonferroni posttest.

B) Plasma 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). *p<0.05 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.01 between hBNP-054 and vehicle by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.01 vs vehicle Bonferroni posttest.

C) Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP). *p<0.001 vs BL one-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test. P=0.004 between hBNP-054 and vehicle groups by two-way ANOVA. †p<0.001 vs hBNP-054, ‡p<0.001 vs ANG II Bonferroni posttest.

During ANG II infusion, plasma cGMP was not activated after vehicle. In contrast, cGMP levels significantly increased after oral hBNP-054 (p=0.01 between two groups) (Figure 6B). This plasma increase in cGMP, after hBNP-054, lasted for 2 hours (p<0.05 vs BL) and it was significantly greater than vehicle at 10, 30 and 60 min (p<0.01) (Figure 6B).

MAP was significantly increased during infusion of ANG II throughout the study in both hBNP-054 and vehicle group. However, while no changes occurred in MAP after vehicle administration, oral hBNP-054 was followed by a significant reduction in MAP for over 2 hours (from 138±2 after ANG II to 124±2 at 30 min, 124±2 and 130±2 mmHg at 1 and 2 hours after oral hBNP-054 respectively; p=0.004) (Figure 6C).

DISCUSSION

BNP is an endogenous peptide produced by the heart under physiological and pathological conditions. It possesses natriuretic, diuretic, vasorelaxant, lusitropic, anti-aldosterone and anti-fibrotic actions that could mediate cardiorenal protection in cardiovascular diseases 7,21. Its plasma concentration increases progressively in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) and has also been reported to be increased in hypertensive heart disease when accompanied by left ventricular hypertrophy 22,23. In advanced CHF, increased immunoreactive BNP may not reflect the biologically active BNP1-32 but represent unprocessed proBNP1-108 which lacks biological activities 24,25. In hypertension (HTN), there are varying findings on BNP levels. Although studies have reported an increase in BNP levels in patients with HTN with left ventricular hypertrophy 23,26,27, more in depth analysis have shown that early stages of HTN are characterized by a lack of activation of BNP that begins to rise only in later stages of the disease process 11. Nevertheless, despite this increase in circulating BNP in cardiovascular disease states, exogenous administration in experimental and human HTN and CHF may have favorable actions 28,29.

Use of recombinant human BNP has been approved for the treatment of acute CHF since 2001. Colucci et al. reported the beneficial actions on cardiovascular hemodynamics of acute intravenous BNP (nesiritide) in patients with decompensated CHF 30. New data from the NAPA trial support the prolonged use of BNP in patients with left ventricular dysfunction undergoing cardiac surgery providing renal protection 31. In agreement with such observations we previously reported that repeated chronic SQ administration of native BNP for 10 days during the evolution of left ventricular dysfunction in a model of mild CHF resulted in an improvement of cardiac hemodynamics 32. More recently, Chen et al. extended these data in human CHF patients, once again demonstrating the potential beneficial effects of chronic BNP therapy 33. Further, in experimental HTN, long acting SQ BNP fused to albumin induced a sustained blood pressure reduction in spontaneously hypertensive rats 34.

The therapeutic use of peptides continues to increase as they are generally characterized by high potency and few adverse events, yet their administration has almost exclusively been relegated to either intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection. While oral administration would be preferred in many cases, potential denaturation in the stomach, proteolysis in the stomach and small intestine, and insufficient transport across the intestinal mucosa and epithelium have proven to be formidable barriers. Although many efforts are underway to deliver native peptides orally via novel formulation technologies 35, the approach used for oral BNP has been based upon derivatization of the therapeutic peptide with small, amphiphilic oligomers that are monodispersed and are comprised of both a hydrophobic (alkyl) moiety and a hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) moiety.

Although, hBNP-021 was the first orally active conjugate discovered, continued research led to the superior conjugates hBNP-050 and hBNP-054 as studied in vivo in the current studies. Both of these derivatives are monoconjugates in which the respective oligomers are attached to the lysine 3 position. Because binding to the NPR-A was believed to occur mostly in the loop region, it had been hypothesized that activity could be compromised upon conjugation to lysine 14 and perhaps lysine 27. Indeed, it was later shown that conjugation at either of these two sites resulted in a loss of both potency and activity. In contrast, conjugation at lysine 3 resulted in virtually complete retention of activity 15.

In the current study we chose the conjugated form of hBNP (hBNP-054) that in normal dogs possessed the most favorable profile in terms of blood pressure lowering and synthesis. This novel conjugated form of BNP (Figure 2) induced a significant increase of plasma hBNP 10 minutes after its oral administration and remained detectable in the circulation for 4 hours. While a formal pharmacokinetic study was not part of the current investigation, the detection of hBNP in canine plasma up to 4 hrs after oral administration of hBNP-054 in all treated dogs, may underscore an extended half life of this new conjugated BNP as compared to native BNP that has a half of approximately 20 minutes. Alternatively, the presence of hBNP in the circulation up to 4 hours after administration of hBNP-054, may reflect different absorption rate. Therefore, more formal pharmacokinetic studies with intravenous injection of a bolus of hBNP-054 are necessary. Only oral hBNP-054, but not native BNP, significantly activated cGMP. Further, the increased levels of hBNP and cGMP after oral hBNP-054 administration induced a significant and sustained reduction of MAP for the duration of the entire study. Of note, we observed different levels of plasma hBNP after oral conjugated hBNP among dogs underscoring the need for continued improvement in this technology to optimize bioavailability and reproducibility in both animals and humans.

We were also able to demonstrate that chronic oral conjugated human BNP administration maintained its biological actions as shown by a significant reduction of MAP after oral hBNP-054 for the 6 days of administration (Figure 4A). The sustained biological actions of hBNP-054 were further demonstrated by a continuous rise in sodium excretion which was followed by a marked reversal of effect when oral hBNP-054 was discontinued (Figure 5). Due to limited hBNP-054, chronic studies were performed in only 2 dogs. These data taken together show that hBNP-054 did not lead to tachyphylaxis nor resulted in signs of accumulation during the study period.

Finally, we demonstrated that this novel orally active conjugate form of human BNP reduces blood pressure in experimental HTN. While there are numerous drugs available for HTN, BNP emerges as going beyond blood pressure reduction alone as it possesses a pleotropic set of beneficial cellular and tissue protective properties warranting further studies and more refined technology to enhance bioavailability and improved pharmacokinetics. The use of a model of acute HTN can be view as a limitation. However, this model of ANG II mediated acute HTN has been extensive in the past and has been used in key studies in the development of anti-hypertensive agents36-41. Importantly, whether BNP mediated antihypertensive properties have advantages over other antihypertensive mechanisms remains to be seen.

In conclusion, we report a novel form of conjugated hBNP that is absorbed and detectable in the circulation when administered orally. Furthermore, conjugated hBNP was capable of activating cGMP and reducing MAP even when administered in a model of acute HTN, and displayed a magnitude and duration of action superior to native hBNP. These data suggest the importance of pursuing further studies with oral administration of conjugated forms of human BNP for the long-term treatment of cardiovascular diseases such as HTN and perhaps overt CHF thus opening a new and innovative phase of cardiovascular therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

FOUNDING SOURCES

This study was supported by grants RO1 HL-36634, PO1 HL76611, and TG HL-07111 from the National Institutes of Health, by Grant 0365411Z from the American Heart Association, by the Mayo Foundation, and by the Italian Ministry of Research (MIUR) Progetto Rientro dei Cervelli.

Footnotes

Subject Heads: 118; 130

DISCLOSURES

There are no disclosures for this manuscript.

While B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) has been approved as an intravenous agent for acute heart failure (HF), increasing research suggests that an additional prime clinical target may be human hypertension to complement its therapeutic use in HF in which molecular forms with reduced biological actions have been reported. Several lines of investigation support a strategy for the therapeutic use of BNP or other natriuretic peptides for hypertension. The evidence includes relative deficiency of biologically active BNP in the early stages of hypertension, ability to chronically enhance sodium excretion and reduce blood pressure as demonstrated in the current studies, potent anti-fibrotic and pro-lusitropic actions and ability to suppress aldosterone synthesis and release. Importantly, in hypertension we take advantage of the blood pressure lowering effects that characterize the inherent properties of the natriuretic peptides, while this effect is a potential limitation for their indiscriminate use in HF patients. What is lacking in clinical practice, however, is the ability to chronically deliver peptides other than via subcutaneous injections. Our report ushers in a new day in protein therapeutics in which we see the ability of advanced alkylPEGylation that modifies the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of BNP permitting its chronic oral delivery. As stated in population studies from Canada, the rise in hypertension prevalence will likely far exceed the predicted prevalence for 2025 and strategies to manage hypertension and its sequelae are urgently needed. We advance now the concept for cardiovascular disease that the chronic use of natriuretic peptides like oral BNP as therapeutic agents will prove highly attractive.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saito Y, Nakao K, Itoh H, Yamada T, Mukoyama M, Arai H, Hosoda K, Shirakami G, Suga S, Minamino N, Kangawa H, Matsuo H, Imura H. Brain natriuretic peptide is a novel cardiac hormone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;158:360–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(89)80056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kambayashi Y, Nakao K, Mukoyama M, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Shiono S, Inouye K, Yoshida N, Imura H. Isolation and sequence determination of human brain natriuretic peptide in human atrium. FEBS Lett. 1990;259:341–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80043-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Hosoda K, Suga S, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Shirakami G, Jougasaki M, Obata K, Yasue H. Brain natriuretic peptide as a novel cardiac hormone in humans. Evidence for an exquisite dual natriuretic peptide system, atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1402–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI115146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan W, Sheng N, Seto M, Morser J, Wu Q. Corin, a mosaic transmembrane serine protease encoded by a novel cDNA from human heart. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14926–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Yandle TG, Espiner EA, Nicholls MG, Richards AM. Treatment of heart failure guided by plasma aminoterminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-BNP) concentrations. Lancet. 2000;355:1126–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper JD, Scarman AL, Clarke BE, Normyle JF, Antalis TM. Localization of the mosaic transmembrane serine protease corin to heart myocytes. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6931–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:321–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cataliotti A, Boerrigter G, Costello-Boerrigter LC, Schirger JA, Tsuruda T, Heublein DM, Chen HH, Malatino LS, Burnett JC., Jr. Brain natriuretic peptide enhances renal actions of furosemide and suppresses furosemide-induced aldosterone activation in experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:1680–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124064.00494.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataliotti A, Burnett JC., Jr. Natriuretic peptides: novel therapeutic targets in heart failure. J Investig Med. 2005;53:378–84. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cataliotti A, Chen HH, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr. Natriuretic peptides as regulators of myocardial structure and function: pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. Heart Fail Clin. 2006;2:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belluardo P, Cataliotti A, Bonaiuto L, Giuffre E, Maugeri E, Noto P, Orlando G, Raspa G, Piazza B, Babuin L, Chen HH, Martin FL, McKie PM, Heublein DM, Burnett JC, Jr., Malatino LS. Lack of activation of molecular forms of the BNP system in human grade 1 hypertension and relationship to cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1529–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00107.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowles JW, Esposito G, Mao L, Hagaman JR, Fox JE, Smithies O, Rockman HA, Maeda N. Pressure-independent enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:975–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver PM, Fox JE, Kim R, Rockman HA, Kim HS, Reddick RL, Pandey KN, Milgram SL, Smithies O, Maeda N. Hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and sudden death in mice lacking natriuretic peptide receptor A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietz JR, Landon CS, Nazian SJ, Vesely DL, Gower WR., Jr. Effects of cardiac hormones on arterial pressure and sodium excretion in NPRA knockout mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:813–8. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller MA, Malkar NB, Severynse-Stevens D, Yarbrough KG, Bednarcik MJ, Dugdell RE, Puskas ME, Krishnan R, James KD. Amphiphilic conjugates of human brain natriuretic peptide designed for oral delivery: in vitro activity screening. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:267–74. doi: 10.1021/bc0501000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James KD, Radhakrishnan B, Malkar NB, Miller MA, Ekwuribe NM. Preparation of modified natriuretic conjugates. Chem Abstr. 2004;141:38847. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin FL, Stevens TL, Cataliotti A, Schirger JA, Borgeson DD, Redfield MM, Luchner A, Burnett JC., Jr. Natriuretic and antialdosterone actions of chronic oral NEP inhibition during progressive congestive heart failure. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1723–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cataliotti A, Malatino LS, Jougasaki M, Zoccali C, Castellino P, Giacone G, Bellanuova I, Tripepi R, Seminara G, Parlongo S, Stancanelli B, Bonanno G, Fatuzzo P, Rapisarda F, Belluardo P, Signorelli SS, Heublein DM, Lainchbury JG, Leskinen HK, Bailey KR, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr. Circulating natriuretic peptide concentrations in patients with end-stage renal disease: role of brain natriuretic peptide as a biomarker for ventricular remodeling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1111–9. doi: 10.4065/76.11.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grantham JA, Borgeson DD, Burnett JC., Jr. BNP: pathophysiological and potential therapeutic roles in acute congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1077–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher RA. Combining independent tests of significance. American Statistician. 1948;2:30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cataliotti A, Chen HH, James KD, Burnett JC., Jr. Oral brain natriuretic peptide: a novel strategy for chronic protein therapy for cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:10–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei CM, Heublein DM, Perrella MA, Lerman A, Rodeheffer RJ, McGregor CG, Edwards WD, Schaff HV, Burnett JC., Jr. Natriuretic peptide system in human heart failure. Circulation. 1993;88:1004–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohno M, Horio T, Yokokawa K, Murakawa K, Yasunari K, Akioka K, Tahara A, Toda I, Takeuchi K, Kurihara N, Takeda T. Brain natriuretic peptide as a cardiac hormone in essential hypertension. Am J Med. 1992;92:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90011-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkridge AM, Heublein DM, Bergen HR, 3rd, Cataliotti A, Burnett JC, Jr., Muddiman DC. Quantitative mass spectral evidence for the absence of circulating brain natriuretic peptide (BNP-32) in severe human heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17442–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang F, O’Rear J, Schellenberger U, Tai L, Lasecki M, Schreiner GF, Apple FS, Maisel AS, Pollitt NS, Protter AA. Evidence for functional heterogeneity of circulating B-type natriuretic peptide. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1071–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freitag MH, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Wilson PW, Vasan RS. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels and blood pressure tracking in the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2003;41:978–83. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000061116.20490.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda T, Kohno M. Brain natriuretic peptide in hypertension. Hypertens Res. 1995;18:259–66. doi: 10.1291/hypres.18.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen HH, Cataliotti A, Schirger JA, Martin FL, Burnett JC., Jr. Equimolar doses of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides and urodilatin have differential renal actions in overt experimental heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1093–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00682.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisel AS. Nesiritide: a new therapy for the treatment of heart failure. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2003;3:37–42. doi: 10.1385/ct:3:1:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colucci WS, Elkayam U, Horton DP, Abraham WT, Bourge RC, Johnson AD, Wagoner LE, Givertz MM, Liang CS, Neibaur M, Haught WH, LeJemtel TH, Nesiritide Study Group Intravenous nesiritide, a natriuretic peptide, in the treatment of decompensated congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:246–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mentzer RM, Jr., Oz MC, Sladen RN, Graeve AH, Hebeler RF, Jr., Luber JM, Jr., Smedira NG. Effects of perioperative nesiritide in patients with left ventricular dysfunction undergoing cardiac surgery:the NAPA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:716–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen HH, Grantham JA, Schirger JA, Jougasaki M, Redfield MM, Burnett JC., Jr. Subcutaneous administration of brain natriuretic peptide in experimental heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1706–12. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen HH, Redfield MM, Nordstrom LJ, Horton DP, Burnett JC., Jr. Subcutaneous administration of the cardiac hormone BNP in symptomatic human heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Ou Y, Shi Y. AlbuBNP, a recombinant B-type natriuretic peptide and human serum albumin fusion hormone, as a long-term therapy of congestive heart failure. Pharm Res. 2004;21:2105–11. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000048203.30568.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morcol T, Nagappan P, Nerenbaum L, Mitchell A, Bell SJ. Calcium phosphate-PEG-insulin-casein (CAPIC) particles as oral delivery systems for insulin. Int J Pharm. 2004;277:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smits GJ, Koepke JP, Blaine EH. Reversal of low dose angiotension hypertension by angiotensin receptor antagonists. Hypertension. 1991;18:17–21. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang CT, Zou LX, Navar LG. Renal responses to AT1 blockade in angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:535–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huelsemann JL, Sterzel RB, McKenzie DE, Wilcox CS. Effects of a calcium entry blocker on blood pressure and renal function during angiotensin-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 1985;7:374–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorbea-Oppliger VJ, Fink GD. Clonidine reverses the slowly developing hypertension produced by low doses of angiotensin II. Hypertension. 1994;23:844–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.d’Uscio LV, Moreau P, Shaw S, Takase H, Barton M, Luscher TF. Effects of chronic ETA-receptor blockade in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;29:435–41. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imagawa J, Kusaba-Suzuki M, Satoh S. Preferential inhibitory effect of nifedipine on angiotensin II-induced renal vasoconstriction. Hypertension. 1986;8:897–903. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.8.10.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]