Abstract

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is critical for phagocyte anti-microbial activity and plays a major role in innate immunity. Defects in genes coding for components of the NADPH oxidase enzyme system are responsible for chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare primary neutrophil immunodeficiency associated with recurrent, life-threatening bacterial and fungal infections. Microbial killing and digestion within the neutrophil phagosomal compartment are defective in these patients. NADPH oxidase activity is also crucial for optimal macrophage and dendritic cell function and has recently been implicated in both cross-presentation and T-cell priming. We present evidence of impaired macrophage function in CGD, with attenuated pro-inflammatory cytokine and increased interleukin-10 secretion following bacterial stimulation. These results highlight additional abnormalities in macrophage function associated with CGD and the importance of NADPH oxidase activity in immunity.

Keywords: chronic granulomatous disease, inflammation, macrophage, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a rare primary immunodeficiency affecting approximately 1/250 000 live births.1 The underlying defect is caused by one of several mutations in genes that encode any of four subunits of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex. Mutations abrogate or grossly attenuate enzyme activity compromising the respiratory burst.2 The most common mutation occurs in the CYBB (gp91phox) gene on the X chromosome and accounts for approximately 65% of cases (X-linked). The remaining genes are autosomal: NCF1 (p47phox), NCF2 (p67phox) and CYBA (p22phox); these cause approximately 25%, 5% and 5% of cases, respectively.3 NADPH oxidase activity is required for the anti-microbial function of phagocytic cells and patients with CGD are therefore highly susceptible to a range of bacterial and fungal pathogens and granulomatous inflammation.1 Current therapeutic regimens employ prophylactic antibiotics and antifungal agents, with additional interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in selected cases.4,5 Although efficient, prophylaxis is imperfect and resultant acute infections require aggressive antimicrobial treatment. Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been successfully employed in CGD and is currently the only proven curative treatment.6 Stem cell gene therapy is currently undergoing intense investigation and providing promising results.4,7,8 The use of autologous stem cells has the potential to eliminate the graft versus host response that can occur in allogeneic transplantations, therefore providing a relatively safe cure for a majority of CGD patients.

Recent investigations have highlighted a role for the NADPH oxidase in the induction of the innate immune system through bacterial recognition and toll-like receptor (TLR) signalling.9–12 The interaction between the TLR and NADPH oxidase has been shown to be highly complex. The TLR signalling causes up-regulation of NADPH oxidase expression in dendritic cells resulting in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and phagosomal alkalinization.12,13 The biological significance of this is reduced proteolysis within the phagosome and cross-presentation of antigenic peptides via major histocompatibility complex class I to the adaptive immune system.14 Dendritic cells derived from mice deficient in NADPH oxidase activity (gp91phox−/−) show impaired antigen processing and subsequent defective T-cell activation. The NADPH oxidase has also been shown to act directly in TLR signalling resulting in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines.10,11 The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor TLR4 activates a diverse array of signalling pathways, one of which is dependent on the activity of NADPH oxidase.10 It is therefore apparent that the appropriate immunological response to microbial challenge by professional antigen-presenting cells requires the activation of the NADPH oxidase system. Macrophages and dendritic cells from CGD patients will potentially respond abnormally to antigenic stimulation. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from CGD patients demonstrate an enhanced inflammatory response after TLR stimulation.15 In addition, macrophages from these patients have been shown to release diminished levels of the anti-inflammatory mediators prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) during phagocytosis of both non-opsonized and opsonized apoptotic targets.16 These two studies clearly illustrate abnormal inflammatory responses in patients with defective NADPH oxidase activity. Here we demonstrate abnormal macrophage function in CGD, with attenuated pro-inflammatory cytokine and elevated IL-10 release after bacterial exposure and TLR activation.

Materials and methods

Patients

These studies were approved by the Joint UCL/UCLH Committee for the Ethics of Human Research (project numbers 02/0324). Five patients with long standing CGD were used in all the studies. Four males were X-linked and one female was deficient in p47phox. Healthy controls were identified through the Department of Medicine, University College London (UCL). Patient details including current treatment and inflammatory status can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics for patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)

| CGD patient | Phenotype | Clinical diagnosis | Haemoglobin (g/dl) | WBC (× 109/l) | Platelets (109/l) | CRP (mg/ml) | Current medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X-linked | Recurrent skin abscesses, inflammatory bowel disease, retro-orbital abscess | 13·5 | 6·31 | 344 | 6 | Septrin, itraconazole, sulphasalazine |

| 2 | X-linked | Recurrent skin abscesses, inflammatory bowel disease with perianal fistula, recurrent lymphadenopathy, previous liver abscesses | 12·8 | 4·86 | 213 | < 1 | Ciprofloxacin, itraconazole, pentasa |

| 3 | X-linked | Recurrent skin abscesses, perianal fistula | 14·2 | 6·19 | 253 | 5 | Septrin, itraconazole |

| 4 | X-linked | Previous chest infection (Aspergillus and mycoplasma) | 16·7 | 3·39 | 312 | < 1 | Septrin, itraconazole |

| 5 | p47phox | Previous pan proctocolitis with pseudopolyposis, granulomatous tenosynovitis, osteoporosis | 15·9 | 4·9 | 489 | 5 | Septrin, voriconazole, prednisolone, folic acid, calcichew, alendronate, inhaler, qvar inhaler, salbutamol |

Healthy levels of inflammatory markers; haemoglobin 11·5–17·5 g/dl, white blood cell count (WBC) 4·1–11 × 109/l, platelets 140–400 × 109 and C-reactive protein (CRP) 0–6 mg/ml.

Macrophage isolation and culture and stimulation

Peripheral venous blood was collected from subjects into syringes containing 5 U/ml heparin. Mononuclear cells were isolated by differential centrifugation (900 g, 30 min, 20°) over Lymphoprep and washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Paisley, UK) at 300 g (5 min, 20°). Cells were resuspended in 10 ml RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 100 U/ml of penicillin (Gibco), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) and 20 mm HEPES pH 7·4 (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK), and plated at a density of approximately 5 × 106 cells/ml in 8-cm2 Nunclon™ Surface tissue culture dishes (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at 37°, 5% CO2. After 2 hr, non-adherent cells were discarded and 10 ml fresh RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each tissue culture dish. Cells were then cultured for 5 days at 37° in 5% CO2, with the addition of a further 10 ml fresh 10% FBS/RPMI-1640 after 24 hr.

Adherent cells were scraped on day 5 and re-plated in 96-well culture plates at equal densities (105/well) in X-Vivo-15 medium (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD). These primary monocyte-derived macrophages were incubated overnight at 37° in 5% CO2, and then stimulated for 24 hr with either 2·5 × 105 HkEc (prepared as previously described 27), Pam3-CSK4 (2 μg/ml) or LPS (200 ng/ml) (Invitrogen).

H2O2 release after macrophage stimulation

Macrophages (105/well) were washed in endotoxin-free PBS (Gibco) and 100 ml PBS containing 100 μm Amplex® Red (Invitrogen) and 0·25 U/ml horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) plus either 1 μg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma), 2·5 × 105 HkEc, 2 μg/ml Pam3-CSK4 or 200 ng/ml LPS plus or minus 5 μm diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI; Sigma). The change in fluorescence was monitored for 1 hr in a microplate reader (FLUOstar Omage; BMG Labtech, Aylesbury, UK), excitation 544 nm and emission detection at 590 nm. Results expressed as rate of H2O2 production per hour.

Macrophage viability

The numbers of viable macrophages after in vitro culture (6 days) and after 24 hr stimulation were ascertained with the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrozolium bromide, tetrazolium salt (MTT) assay (Boehringer Ingelheim, Berkshire, UK). Briefly, 20 μl of 2 mg/ml MTT was added to each well and incubated for 4 hr at 37° in 5% CO2. Supernatants were carefully discarded and 100 μl/well of lysis solution [90% isopropanol, 0·5% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 0·04 m HCl, 10% H2O] was added to each well for 1 hr at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 570 nm using a microplate reader (FLUOstar Omage; BMG Labtech).

Cytokine secretion assays

Macrophage supernatants were collected after 24 hr stimulation of primary monocyte-derived macrophages with HkEc, LPS or Pam3-CSK4 as previously described. The expression profile of a panel of cytokines in macrophage supernatants was measured using the Beadlyte Bio-Plex™ human cytokine assay (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Our assay was customized to detect and quantify interleukin (IL)-1Ra, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP-1β), IL-6, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IL-13, IFN-γ and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). Cytokine release in culture supernatants was normalized for the numbers of viable cells in each well, ascertained with the MTT assay (see above).

FACS analysis

Cells were prepared as described above. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was carried out on cells double-stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD14 (Sigma) and phycoerythin-conjugated anti-CD16 (BD Pharmingen™, Oxford, UK). The percentage of M1 (CD14+ CD16−) and M2 (CD14+ CD16+) cells was calculated from the CD14+ population. Results are expressed as the mean value ± SD.

Results

Bacterial and TLR-induced NADPH oxidase activity in macrophages

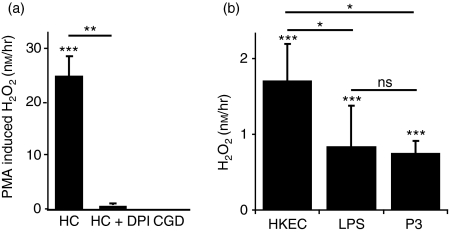

Human macrophages were exposed to PMA and the generation of H2O2 was determined (Fig. 1a). Macrophages from healthy controls released significant quantities of H2O2 after PMA exposure. The inclusion of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI resulted in almost complete loss in H2O2 release (∼ 98%). Macrophages derived from CGD patients were unable to generate any detectable H2O2 after PMA exposure.

Figure 1.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity in macrophages. (a) Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) results in the activation of NADPH oxidase in healthy control (HC) macrophages (n = 21), whereas there was no detectable activity in macrophages from patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; n = 3). In the presence of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI H2O2 release was reduced by 98% (n = 3). (b) HC macrophages (n = 11) stimulated with HkEc, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Pam3-CSK4 (Pam3) resulted in significant NADPH oxidase activation. All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

Macrophages from healthy controls were used to determine the level of NADPH oxidase activity after bacterial [heat-killed Escherichia coli (HkEc)], TLR4 (LPS) and TLR2 (Pam3-CSK4) stimulation (Fig. 1b). All three stimuli resulted in significantly higher H2O2 release compared with unstimulated macrophages. Exposure to HkEc produced a greater quantity of H2O2 than either of the TLR ligands. These results show that macrophages that are stimulated by either whole bacteria or highly purified TLR ligands activate the NADPH oxidase system resulting in ROS production.

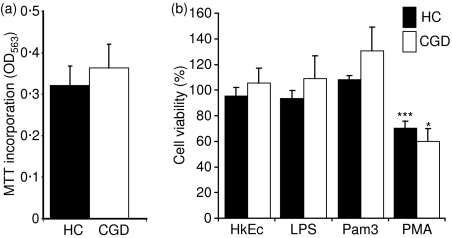

Macrophage viability after stimulation

A previous report identified an abnormal neutrophil apoptotic response in CGD.16 Neutrophils in these patients were shown to be more resistant to spontaneous apoptosis in culture than those from healthy controls. Spontaneous in vitro loss of macrophage viability, as determined by MTT incorporation, was not significantly different in between CGD patients and healthy control subjects after 6 days in culture (Fig. 2a). Stimulation with HkEc, LPS and Pam3-CSK4 had no effect after 24 hr on viability in either group (Fig. 2b), whereas, PMA caused significant cell death in both groups. These results suggest that, unlike in neutrophils, loss of NADPH oxidase activity has no affect on macrophage viability in vitro.

Figure 2.

Macrophage viability after: (a) 6 days in vitro; (b) 24 hr stimulation with HkEc, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Pam3-CSK4 (Pam3) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). Increased cell death was only observed after PMA stimulation and there was no significant difference between healthy controls (HC; n = 17) and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; n = 3) macrophages. All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *P < 0·05, ***P < 0·001.

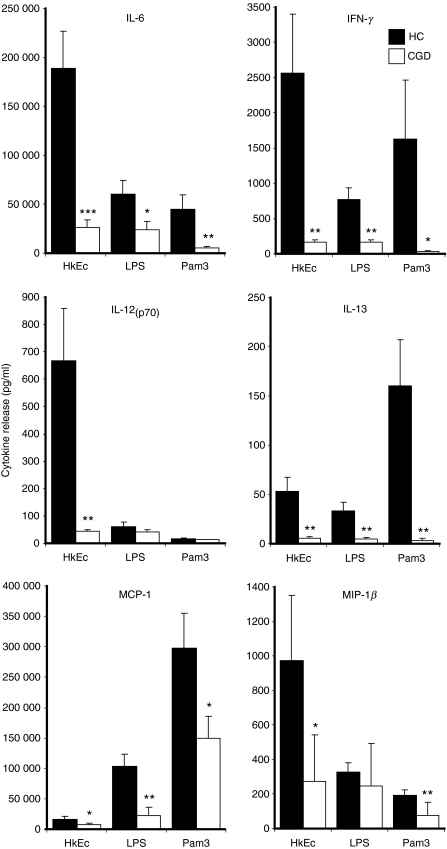

Pro-inflammatory cytokine release after bacterial and TLR stimulation

Pro-inflammatory cytokines have previously been described as elevated in PBMC from CGD patients after TLR stimulation.15 We therefore assessed the effects of HkEc, LPS and Pam3-CSK4 on pro-inflammatory cytokine release by healthy control and CGD macrophages. In contradiction to the findings in PBMC, CGD macrophages released significantly lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines after 24 hr stimulation (Fig. 3). Interleukin-6, MCP-1, IL-13 and IFN-γ were reduced with all stimuli, whereas MIP-1β was diminished with HkEc and IL-12(p70) was lower with both HkEc and Pam3-CSK4. The CGD macrophages released normal levels of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-8 after LPS and Pam3-CSK4 stimulation (data not shown). The expression levels of TLR2 and TLR4 were similar between CGD and healthy control cells (data not shown). Abnormal cytokine release seemed to be associated more strongly with HkEc exposure, which may reflect the increased NADPH oxidase activity normally induced by this stimulus (Fig. 2b).

Figure 3.

Pro-inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages stimulated for 24 hr with HkEc, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Pam3-CSK4 (Pam3). Diminished cytokine release was associated with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; n = 5) macrophages compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 15). All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001.

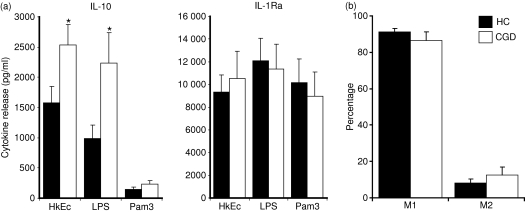

Increased secretion of IL-10 after macrophage stimulation

Decreased macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine release in CGD may result from a partial or complete inability to respond to an antigenic stimulus after in vitro culture. We therefore tested macrophage supernatants for the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10 and IL-1ra, after HkEc, LPS and Pam3-CSK4 stimulation. Whereas pro-inflammatory cytokine release was attenuated in CGD macrophages, anti-inflammatory cytokine release was normal (IL-1ra) or elevated (IL-10) (Fig. 4a). Release of IL-10 was significantly greater after HkEc and LPS stimulation. The altered cytokine profile observed in CGD did not result from an abnormal polarization in macrophage phenotype. The percentages of M1 (CD14+ CD16−) and M2 (CD14+ CD16+) macrophages were not significantly different in CGD patients and healthy controls (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Anti-inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages stimulated for 24 hr with HkEc, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Pam3-CSK4 (Pam3). Elevated interleukin-10 (IL-10) was associated with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; n = 5) macrophages compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 15) after HkEc and LPS stimulation. (b) M1 (CD14+ CD16−) and M2 (CD14+ CD16+) macrophage populations determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. All results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *P < 0·05.

It seems that the activation of NADPH oxidase after bacterial and TLR stimulation results in the generation of ROS, which in turn affects the cytokine secretory profile of the macrophage. Normal NADPH oxidase activity results in an increased pro-inflammatory and reduced anti-inflammatory cytokine release.

Discussion

This study shows that the macrophage response to antigenic challenge differs significantly in CGD and HC. Macrophage stimulation with whole bacteria and pure bacterially derived TLR ligands generates ROS that play a role in the release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. A lack of ROS in CGD has a profound effect on macrophage cytokine release, resulting in greatly diminished pro-inflammatory and elevated anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine secretion. The precise role NADPH oxidase plays in this complex process in still unclear. In addition, the NADPH oxidase does not seem to play a major role in macrophage viability in vitro. This is in direct contrast to neutrophils in CGD, which are more resistant to apoptotic cell death.16

In accordance with standard clinical practice in such patients, all the CGD patients in this study were on antimicrobial prophylaxis. Although such therapy could potentially influence the immune response, we were unable to identify any phenotypic differences in the macrophage population in CGD patients. This does not rule out the possibility that antimicrobial therapy could have an alternative effect on the immunological response. A more detailed investigation will be needed to fully address this point.

TLR4 activates a diverse array of signalling pathways, one of which has been shown to be dependent on the activity of NADPH oxidase.10 Stimulation with TLR4 results in the formation of the signalling complex tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6/apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (TRAF6/ASK1), which is dependent on the generation of ROS via NADPH oxidase. The TRAF6/ASK1 results in the sustained activation of the Jun N-terminal kinase/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases.11 The induction of the TLR4–NADPH oxidase-dependent pathway results in the increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6). Inhibition of ROS generation by the inclusion of anti-oxidants resulted in a significant decrease in cytokine synthesis upon TLR4 stimulation with LPS.10 NADPH oxidase activation is not restricted to TLR4 as work by Miletic et al. demonstrated that NADPH oxidase is downstream of the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88),17 providing evidence that the NADPH oxidase can be activated down all TLR except TLR3. Our results also demonstrate TLR2-induced ROS production and abnormal macrophage cytokine release in CGD macrophages after Pam3-CSK4 stimulation. Precisely how TLR signalling activates the NADPH oxidase is still not fully understood, but recruitment of the NADPH subunits to the plasma membrane involves interleukin receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), which phosphorylates p47phox and regulates oxidase activation.18

The pattern of macrophage cytokine release observed here in CGD differed from that reported for PBMC.15 The PBMC population used in the aforementioned study consisted predominantly of lymphocytes (B and T cells) with only a small proportion of monocytes. B cells and monocytes both contain the NADPH oxidase components19 and all PBMC are able to respond either directly or indirectly to the antigenic stimuli used. In our study we used purified macrophages that were matured in vitro for 6 days before activation. In support of an increase in macrophage anti-inflammatory cytokine release in CGD, Warris et al.20 reported elevated IL-10 secretion in whole blood activated by exposure to Aspergillus fumigatus. A recent report using gp91phox-deficient mice described the constitutive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages removed from the peritoneum.21 We were unable to detect cytokines from unstimulated human CGD monocyte-derived macrophages. This discrepancy may be to the result of differences in experimental procedures. Mouse macrophages were harvested, plated ex vivo and cytokines were measured 6 hr later. In the experiments presented here we used peripheral monocytes cultured for 5 days before 24 hr of microbial stimulation.

The NADPH oxidase activity may also have anti-inflammatory properties.22–25 A major role of the NADPH oxidase in an anti-inflammatory capacity is centred on neutrophil apoptosis and the induction of resolution.24,25 The precise role NADPH oxidase plays in resolution of inflammation seems to be highly complex. Recent papers have identified reduced levels of adenosine and cAMP,23 as well as phosphatidylserine membrane levels on apoptotic neutrophils.24,25 Our observation during the initiation phase of acute inflammation demonstrated increased IL-10 and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by CGD macrophages. This suggests that the NADPH oxidase plays differing roles in the acute and resolving phases of inflammation.

It is clear that the NADPH oxidase complex plays a major part in the immune system, apart from its obvious role in microbial killing. Microbial-induced NADPH oxidase activation and subsequent generation of ROS directly participate in complex inflammatory signalling cascades which ultimately determine the immunological response. Patients with CGD, who are unable to optimally activate these signalling pathways, generate abnormal immune responses that might be detrimental to their well being. It is interesting to note that a long-standing therapeutic regimen for CGD patients is the infusion of recombinant IFN-γ.26 Clinical trials of recombinant IFN-γ have shown a 72% reduction in the relative risk of serious infection compared with placebo. The precise mechanism by which IFN-γ works is still not known.5 Our results demonstrate that macrophages from CGD patients release very low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines after bacterial stimulation, particularly IFN-γ. It is tempting to speculate, therefore, that IFN-γ infusions may correct this deficiency in vivo, thereby improving the immunological response in these patients.

Our data clearly shows that macrophages in patients with CGD have a gross defect in cytokine release after microbial and TLR stimulation. The precise role that NADPH oxidase plays in cytokine secretion is still unclear, but it seems obvious that the generation of ROS during an infection plays a major part in dictating the immunological response.

Acknowledgments

We thank all volunteers for participating in these studies. This work was supported by The CGD Research Trust and The Wellcome Trust.

Disclosures

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dinauer MC. Chronic granulomatous disease and other disorders of phagocyte function. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:89–95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal AW. The NADPH oxidase and chronic granulomatous disease. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:129–35. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrasher AJ, Keep NH, Wientjes F, Segal AW. Chronic granulomatous disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1227:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seger RA. Modern management of chronic granulomatous disease. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:255–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Errante PR, Frazao JB, Condino-Neto A. The use of interferon-gamma therapy in chronic granulomatous disease. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2008;3:225–30. doi: 10.2174/157489108786242378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seger RA, Gungor T, Belohradsky BH, et al. Treatment of chronic granulomatous disease with myeloablative conditioning and an unmodified hemopoietic allograft: a survey of the European experience, 1985–2000. Blood. 2002;100:4344–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barese CN, Goebel WS, Dinauer MC. Gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1423–34. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.9.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goebel WS, Dinauer MC. Gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Acta Haematol. 2003;110:86–92. doi: 10.1159/000072457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang E, Dang O, Anderson K, Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H, David M. Cutting edge: apoptosis-regulating signal kinase 1 is required for reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of IFN regulatory factor 3 by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2006;176:5720–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzawa A, Saegusa K, Noguchi T, et al. ROS-dependent activation of the TRAF6-ASK1-p38 pathway is selectively required for TLR4-mediated innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:587–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T, et al. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinases and apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:222–8. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vulcano M, Dusi S, Lissandrini D, et al. Toll receptor-mediated regulation of NADPH oxidase in human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:5749–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elsen S, Doussiere J, Villiers CL, et al. Cryptic O2–-generating NADPH oxidase in dendritic cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2215–26. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savina A, Jancic C, Hugues S, et al. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126:205–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bylund J, MacDonald KL, Brown KL, et al. Enhanced inflammatory responses of chronic granulomatous disease leukocytes involve ROS-independent activation of NF-kappa B. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1087–96. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown JR, Goldblatt D, Buddle J, Morton L, Thrasher AJ. Diminished production of anti-inflammatory mediators during neutrophil apoptosis and macrophage phagocytosis in chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:591–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miletic AV, Graham DB, Montgrain V, et al. Vav proteins control MyD88-dependent oxidative burst. Blood. 2007;109:3360–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-033662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacquelet S, Johnson JL, Ellis BA, et al. Cross-talk between IRAK-4 and the NADPH oxidase. Biochem J. 2007;403:451–61. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babior BM. The respiratory burst oxidase. Curr Opin Hematol. 1995;2:55–60. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199502010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warris A, Netea MG, Wang JE, et al. Cytokine release in healthy donors and patients with chronic granulomatous disease upon stimulation with Aspergillus fumigatus. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:482–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540310013009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Boyanapalli RF, Frasch SC, McPhillips K, et al. Impaired apoptotic cell clearance in CGD due to altered macrophage programming is reversed by phosphatidylserine-dependent production of IL-4. Blood. 2008;113:2047–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao H, Edirisinghe I, Yang SR, et al. Genetic ablation of NADPH oxidase enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation and emphysema in mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1222–37. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajakariar R, Newson J, Jackson EK, et al. Nonresolving inflammation in gp91phox−/− mice, a model of human chronic granulomatous disease, has lower adenosine and cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate. J Immunol. 2009;182:3262–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hampton MB, Vissers MC, Keenan JI, Winterbourn CC. Oxidant-mediated phosphatidylserine exposure and macrophage uptake of activated neutrophils: possible impairment in chronic granulomatous disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:775–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frasch SC, Berry KZ, Fernandez-Boyanapalli R, et al. NADPH oxidase-dependent generation of lysophosphatidylserine enhances clearance of activated and dying neutrophils via G2A. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33736–49. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807047200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallin JI. Interferon-gamma in the management of chronic granulomatous disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:973–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.5.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marks DJ, Harbord MW, MacAllister R, et al. Defective acute inflammation in Crohn’s disease: a clinical investigation. Lancet. 2006;367:668–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]