Abstract

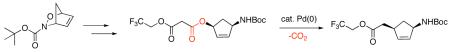

Homoallylic esters are obtained in a single transformation from allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonates by using a Pd(0)-catalyst. Facile decarboxylation of allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonates is attributed to a decrease in pKa compared to allyl methyl malonates. Subsequent reduction of the homoallylic 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl ester provides a (hydroxyethyl)cyclopentenyl derivative that represents a key intermediate in the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides. A select allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonate undergoes a decarboxylative Claisen rearrangement to provide a regioisomeric homoallylic ester.

Homoallylic esters are embedded in the core structures of several classes of natural products including macrolide polyketides,1 α-linolenic acid metabolites and derivatives2 and cyclopentenone prostaglandins.3 Although homoallylic esters may be synthesized in several steps by functional group manipulation,2a direct access to homoallylic esters has been achieved by Krapcho decarboxylation of malonates,4 addition of vinyl radicals to α,β-unsaturated esters5 and 1,4-addition of alkenylcopper reagents.6

We considered metal-catalyzed decarboxylative allylations as an alternative method to directly prepare homoallylic esters under mild conditions.7 Although α-cyano, α-nitro, α-keto8 and α-sulfonyl9 allyl esters readily undergo Pd(0)-catalyzed decarboxylative rearrangements to afford the corresponding homoallylic derivatives, allyl methyl malonates are much less reactive. Their diminished reactivity is attributed to the less stable methoxyethenolate that forms upon decarboxylation. α,α-Dialkyl allyl methyl malonates require harsh conditions (i. e., 120 °C in DMF) to effect Pd(0)-decarboxylative rearrangements.8 Diallyl malonates undergo decarboxylative allylation at room temperature, but must possess an aryl group at the α-position.10 To our knowledge, Pd(0)-decarboxylative rearrangements of α,α-unsubstituted allyl alkyl malonates have not been reported. In order to achieve decarboxylation, we envisioned replacement of the allyl methyl malonate with an allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonate. The strong electron-withdrawing ability of the trifluoroethyl group would improve the stability of the transient alkoxyethenolate and promote decarboxylation. Herein, we disclose that α,α-unsubstituted allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonates are suitable substrates for Pd(0)-catalyzed decarboxylative allylations and provide desired homoallylic 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl esters in high yields.

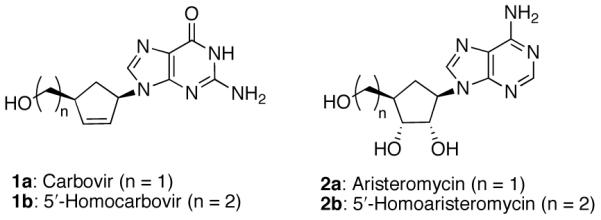

Our group has previously reported Pd(0)-catalyzed allylic alkylations with cycloadduct 311 and related substrates as key steps en route to targeted carbocyclic nucleosides.12 In order to access carbonucleoside targets 5′-homocarbovir 1b13 and 5′-homoaristeromycin 2b,14 we required a reliable method to install the requisite 5′-hydroxyethyl side chain. We envisioned a Pd(0) decarboxylative rearrangement to afford an α-allyl ester and subsequent reduction to the (hydroxyethyl)cyclopentyl core structure. Further elaboration would furnish 1b and 2b (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Carbonucleoside Target Molecules.

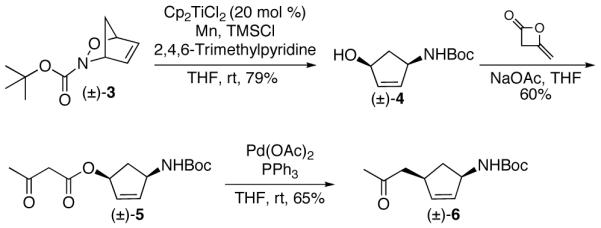

As a model system to explore palladium catalyzed decarboxylative allylation of 1,4-syn disubstituted cyclopentenes, allyl β-keto ester 5 was synthesized in two steps from cycloadduct 3 (Scheme 1).15,16 Allyl β-keto esters are reliable substrates that undergo Pd(0)-catalyzed decarboxylative rearrangements under mild conditions.8,17 The mechanism proceeds through oxidative addition to give a metal β-keto carboxylate/π-allyl system. Upon decarboxylation, nucleophlic attack by the resulting enolate affords ketone products. When allyl β-keto ester 5 was treated with Pd(0), ketone 6 was isolated in 65% yield as the exculsive product with complete diastereo- and regiocontrol. This initial result demonstrated that appropriately functionalized cyclopentenes derived from 4 are suitable substrates for decarboxylative allylations.

Scheme 1.

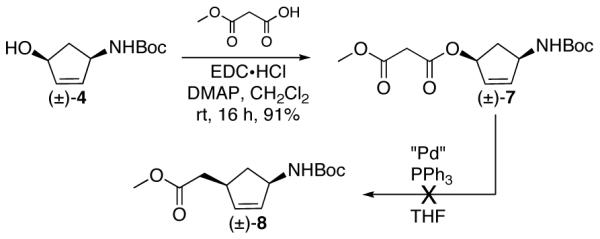

Replacement of the allyl β-keto ester group with an allyl methyl malonate system would provide access to a versatile homoallylic ester sidechain. The ester could be converted to an alcohol or aldehyde and give access to key intermediates in the synthesis of carbonucleosides. Cyclopentenol 4 was coupled to methyl malonate to give allyl methyl malonate 7 in 91% yield. Exposure of 7 to various palladium sources (Pd(OAc)2, Pd(dba)2, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3) and temperatures resulted in no reaction and recovery of starting material (Scheme 2).18

Scheme 2.

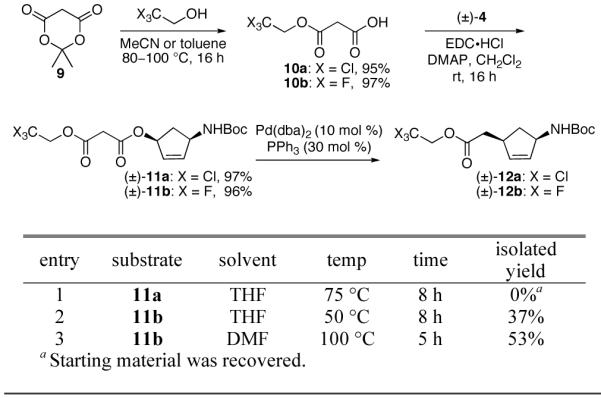

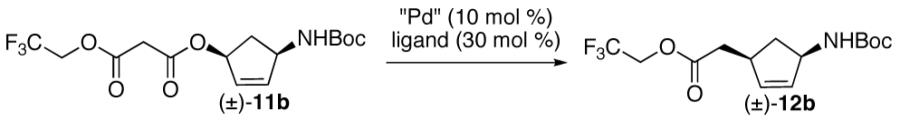

In an attempt to increase stabilization of the anionic intermediate that is formed upon decarboxylation, acids 10a and 10b were coupled with cyclopentenol 4 to form allyl 2,2,2-trichloroethyl malonate 11a and allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonate 11b in high yields, respectively (Scheme 3). Although trichloroethyl derivative 11a did not undergo decarboxylative rearrangement in the presence of Pd(dba)2 and PPh3, trifluoroethyl substrate 11b provided homoallylic ester 12b under similar reaction conditions with complete diastereo- and regiocontrol. The electron withdrawing effect of the trifluoroethyl group plays a significant role in accelerating the decarboxylative rearrangement.

Scheme 3.

Next, we turned our attention to optimizing the reaction conditions for formation of α-allyl ester 12b (Table 1). Accordingly, a series of palladium sources and ligands were investigated with DMF as solvent. The combination of Pd(dba)2 and 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane (dppe) emerged as the optimal source of Pd(0). However, heating the reaction mixture at 100 °C in DMF was undesirable and removal of DMF complicated the purification and isolation process. Several solvents were explored at lower temperatures and ultimately THF proved to be optimal (Table 1, entry 7) and a yield of 82% was obtained.19,20 A control reaction (Table 1, entry 8) in the absence of Pd(0) and ligand was also performed to confirm that the process was not thermally driven. Decomposition of malonate 11b was not observed after stirring at 145 °C in DMF for 16 h. The retention of the 1,4-syn stereochemistry of 12b was expected due to the double inversion via the palladium π-allyl system. The 1,4-syn stereochemistry of ester 12b was confirmed by 1H NMR. A characteristic coupling pattern (J = 6.5, 6.5, 13.5 Hz and J = 7.8, 7.8, 13.5 Hz) was observed for the diastereotopic methylene protons in the cyclopentene core.21

Table 1.

Selected Reaction Conditions for Optimization Studies

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Pd/ligand | solv. | temp | time | isolated yield |

| 1 | Pd(OAc)2 PPh3 |

DMF | 100 °C | 5 h | 40% |

| 2 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 PPh3 |

DMF | 100 °C | 5 h | 40% |

| 3 | Pd(dba)2 P(OPh)3 |

DMF | 100 °C | 8 h | 0%a |

| 4 | Pd(dba)2 rac-BINAP |

DMF | 100 °C | 4 h | 51% |

| 5 | Pd(dba)2 PS-PPh3 |

DMF | 100 °C | 4 h | 56% |

| 6 | Pd(dba)2 dppe |

DMF | 100 °C | 4 h | 60% |

| 7 | Pd(dba)2 dppe b |

THF | 75 °C | 6 hc | 82% |

| 8 | no palladium no ligand |

DMF | 145 °C | 16 h | 0%a |

Starting material was recovered.

Reaction conducted with 5 mol % Pd(dba)2 and 15 mol % dppe resulted in 50% conversion to product (by1H NMR integration) after 6 h.

Longer reactions time (16 h) resulted in lower yield (53%).

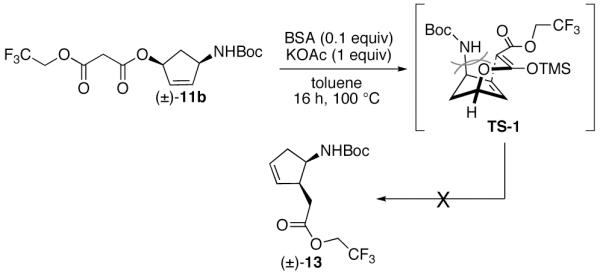

With a reliable method to 1,4-syn cyclopentene derivative 12b established, we turned our attention to the synthesis of 1,2-syn cyclopentene derivative 13 by employing a decarboxylative Claisen rearrangement. The base catalyzed [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement-decarboxylation of tosylmalonic mono(allylic) esters has recently been reported.22 While substrate 11b does not have the additional electron withdrawing Ts group at the α-position, it was envisioned that the increased electron withdrawing effects of the trifluoroester would allow for the rearrangement to occur. Malonate 11b was subjected to N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA) and KOAc in anhydrous toluene at 100 °C (Scheme 4).23 Unfortunately, partial decomposition occurred and product 13 was not detected. This result was not unexpected considering the steric bulk imparted by the Boc-protected amine in pseudo-boat transition state TS-1.

Scheme 4.

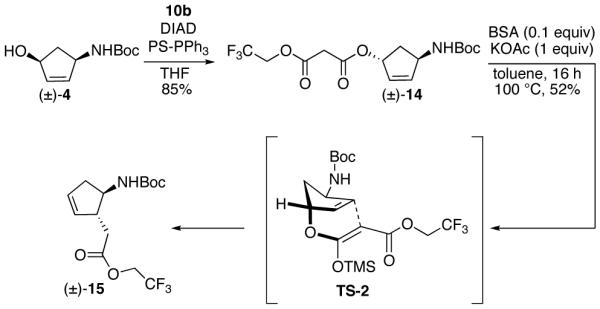

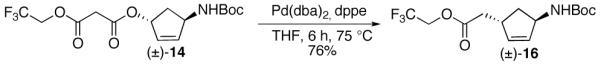

In order to avoid a sterically hindered transition state, we synthesized 1,4-trans diastereomer 14 as a substrate for the decarboxylative Claisen rearragement. Alcohol 4 was subjected to Mitsunobu conditions in the presence of acid 10b to afford 1,4-trans malonate 14 (Scheme 5). Malonate 14 was exposed to the decarboxylative Claisen rearrangement conditions and ester 15 was obtained in 52% yield. The unfavorable boat-like 6-membered transtion state TS-2 could have contributed to the relatively low yield. Malonate 14 also underwent efficient Pd(0)-catalyzed decarboxylative rearrangement to 1,4-trans cyclopentene 16 (Scheme 6).20 The stereochemistry of 15 and 16 was confirmed by analyses of the COSY and/or ROESY NMR spectra.

Scheme 5.

Scheme 6.

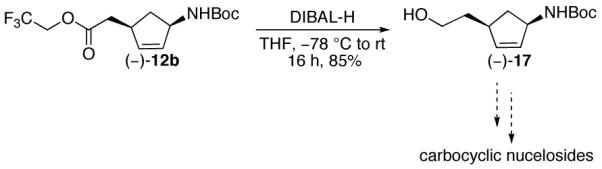

Finally, allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonate (-)-11b was synthesized from the readily available aminocyclopentenol (-)-424 and converted to ester (-)-12b. Treatment with diisobutylaluminum hydride provided alcohol (-)-17 in 85% yield (Scheme 7). Alcohol (-)-17 represents a key intermediate towards the synthesis of (-)-5′-homocarbovir 1b and (-)-5′-homoaristeromycin 2b.

Scheme 7.

In summary, allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonates undergo efficient Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation. Installation of the trifluoroethyl group resulted in improved stabilization of the reactive carbanion intermediate. Simple esters and trichloroethyl ester groups were not effective. We have also identified substrate 14 as a new system for the decarboxylative Claisen rearrangement. Alcohol (-)-17 is currently being used as a key intermediate to synthesize carbocyclic nucleosides. Those investigations will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge Nonka Sevova (University of Notre Dame) for mass spectroscopic analyses, Dr. Jaroslav Zajicek (University of Notre Dame) for NMR assistance, and Dr. Jed Fisher (University of Notre Dame) for helpful discussions. We acknowledge the University of Notre Dame and NIH (GM 068012 and GM 075885) for support of this work.

References

- (1).Sheehan LS, Lill RE, Wilkinson B, Sheridan RM, Vousden WA, Kaja AL, Crouse GD, Gifford J, Graupner PR, Karr L, Lewer P, Sparks TC, Leadlay PF, Waldron C, Martin CJ. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:1702. doi: 10.1021/np0602517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Nonaka H, Wang Y-G, Kobayashi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:1745. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pinot D, Guy A, Fournial A, Balas L, Rossi J-C, Durand T. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3063. doi: 10.1021/jo702455g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Negishi M, Katoh H. Prostag. Oth. Lipid M. 2002;68-69:611. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Acharya H, Kobayashi Y. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:3329. [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Miura K, Itoh D, Hondo T, Hosomi A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9605. [Google Scholar]; (b) Foubelo F, Lloret F, Yus M. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:6715. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cahiez G, Venegas P, Tucker CE, Majid TN, Knochel P. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992;19:1406. [Google Scholar]

- (7).For a review on decarboxylative allylations, see:Tunge JA, Burger EC. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:1715.Dai LX, You SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889.

- (8).Tsuji J, Yamada T, Minami I, Yuhara M, Nisar M, Shimizu I. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:2988. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Weaver J, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4657. doi: 10.1021/ol801951e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Imao D, Itoi A, Yamazaki A, Shirakura M, Ohtoshi R, Ogata K, Ohmori Y, Ohta T, Ito Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1652. doi: 10.1021/jo0621569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Mulvihill MJ, Surman MD, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4874. [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Jiang MX-W, Jin B, Gage JL, Priour A, Savela G, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4164. doi: 10.1021/jo060224l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li F, Brogan JB, Gage JL, Zhang D, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:4538. doi: 10.1021/jo0496796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).For total synthesis of (±)-5′-homocarbovir, see:Rhee H, Yoon D, Jung ME. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2000;19:619. doi: 10.1080/15257770008035012.

- (14).For total synthesis of (-)-5′-homoaristeromycin, see:Roberts SM, Jones MF. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. I. 1988:2927.Yang M, Schneller SW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:149. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.019.

- (15).For N-O bond reductions of cylcloadducts, see:Cesario C, Tardibono L, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:448. doi: 10.1021/jo802184y.

- (16).Diketene reaction conditions adapted from a procedure found in:Collado I, Mazón A, Espinosa JF, Blanco-Urgoiti J, Schoepp DD, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Kingston AE. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:3619. doi: 10.1021/jm0110486.

- (17).Burger EC, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4113. doi: 10.1021/ol048149t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).For a detailed table of reaction conditions, see Supporting Information.

- (19).The reaction is performed under anhydrous conditions in a sealed tube. High yields (76%) were observed on 1.5 mmol scale. Decreased yields (61%) were observed on 6 mmol scale.

- (20).Crude reaction mixture was analyzed by 1H NMR and showed complete consumption of the allyl 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl malonate and the formation of a single product with complete diastereo- and regiocontrol.

- (21).For a brief discussion of coupling constants of 1,4-disubstituted cyclopentenes, see:Mulvihill MJ, Surman MD, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4874.

- (22).Craig D, Grellepois F. Org. Lett. 2005;7:463. doi: 10.1021/ol047577w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).For mechanistic discussions of the decarboxylative Claisen rearrangement, see:Bourgeois D, Craig D, King NP, Mountford DM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:618. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462023.Craig D, Grellepois F, White AJP. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6827. doi: 10.1021/jo050747d.

- (24).Mulvihill MJ, Gage JL, Miller MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3357. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.