Abstract

Previous literature has found greater heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) responses during relived anger, and a positive association between covert hostility and relived anger, in male veterans with PTSD. This study investigated hostility and cardiovascular responses to a relived anger task in 120 women (70 with PTSD and 50 without PTSD). Women with PTSD reported greater hostile beliefs and covert hostility than non-PTSD controls, reported greater anger and anxiety during the anger recall task, and had higher resting HR. In general, the relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular response was moderated by covert hostility, which was associated with greater baseline diastolic BP and greater HR during relived anger and anger recovery among women with PTSD, but not among non-PTSD controls. Results suggest that the relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular response is moderated by hostility.

Keywords: Cardiovascular parameters, PTSD, hostility

Anger and hostility are hallmarks of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Anger and hostility are both higher in people with PTSD than people without PTSD, and they are particularly higher in those suffering from PTSD associated with military experience (Orth & Wieland, 2006). Irritability and outbursts of anger are one of the Cluster D (hyperarousal) symptoms of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Heightened autonomic arousal is also considered to be a hallmark of PTSD (Pole, 2007). This hyperarousal is particularly associated with idiopathic trauma cues, but also has been found in resting baseline physiology, response to startling sounds, and standardized trauma cues (Pole, 2007). Hyperarousal has also been found to anger cues in people with PTSD (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002). Male combat veterans with PTSD had greater mean heart rate (HR) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) response during a standardized anger recall paradigm, and reported greater anger and anxiety during the task, compared to male combat veterans without PTSD. In addition, there was a significant interaction between PTSD status and covert hostility: That is, PTSD moderated the relationship between covert hostility and cardiovascular functioning such that only veterans with PTSD exhibited slower systolic blood pressure (SBP) recovery with higher covert hostility (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002). Although previous studies had found a relationship between cardiovascular reactivity and hostility in nonselected samples (Fredrickson et al., 2000; Suarez, Kuhn, Schanberg, Williams, & Zimmering, 1998), this study found no relationship between these variables in Vietnam combat veterans without PTSD. This suggested that veterans exposed to significant combat trauma who do not develop PTSD may have unusual psychological resilience.

Unfortunately, despite strong evidence linking PTSD and hostility to increased cardiovascular reactivity in men, there has been little investigation of hostility and cardiovascular parameters in women with PTSD (Beckham, Calhoun, Glenn, & Barefoot, 2002). This is a significant limitation of the current literature, as PTSD is more prevalent in women (Olff, Langeland, Draijer, & Gersons, 2007) and there is growing evidence of an association between hostility and cardiovascular outcomes in women (Haynes, Feinleib, & Kannel, 1980; Krantz et al., 2006; Matthews, Owens, Kuller, Sutton-Tyrrell, & Jansen-McWilliams, 1998; Williams et al., 2000). While we have demonstrated that hostility is more strongly related to ambulatory HR and DBP in women with PTSD than women without PTSD (Beckham, Flood, Dennis, & Calhoun, 2009), it remains unknown whether women with PTSD would display similar cardiac response patterns to an anger provocation task as have men with PTSD.

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate self-report and cardiovascular responses (HR, SBP, and DBP) to a standardized anger recall task in women with and without PTSD in order to explore the relationship between PTSD, covert hostility, and cardiovascular outcomes in a direct replication of our study with male veterans (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002). As in this previous work, hostility is considered a stable, attitudinal trait operationalized through a factor analysis of four common hostility questionnaires, and anger is manipulated as a short-term emotional state through recall of a personal anger memory. Based on our previous results with men, it was hypothesized that, compared to women without PTSD, women with PTSD will report higher levels of hostility, demonstrate a greater magnitude of cardiovascular response during and after relived anger, and be more likely to show a significant positive relationship between covert hostility level and response to anger provocation.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited via advertising for a study on trauma and health, and all participants gave informed consent before participating in the study. One hundred and ninety-three participants completed the screening interviews, which included the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (Blake et al., 1995) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis (Spitzer, Williams, & Gibbon, 1995). Sixty-nine were then excluded for the following reasons: lifetime, but not current PTSD (n = 27); current drug or alcohol abuse or dependence or positive drug screen (n = 7); Current or lifetime major depressive disorder (n=29); other psychiatric condition (n = 4),]: [two for psychosis; two for bipolar with current manic symptoms]; and being prescribed a contraindicated medication (amitriptyline, methadone) [n = 2]. Subsequently, 124 participants met enrollment criteria. Another four were excluded from our analyses for having incomplete questionnaire data, resulting in a final dataset of N=120 (70 PTSD, 50 Control). Of the 50 participants in the control condition, 40 (80%) reported a Criterion A traumatic experience in their history.

Measures

Hostility

Cook-Medley Hostility Scale

This measure is an abbreviated form of the original scale consisting of 27 items. Three subscales (cynicism, hostile affect, and aggressive responding) were derived from this instrument (Barefoot, Dodge, Peterson, Dahlstrom, & Williams, 1989; Barefoot, Larsen, Lieth, & Schroll, 1995). The coefficient alpha for this abbreviated form is .86 (Barefoot, Beckham, Haney, Siegler, & Lipkus, 1993).

Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) (Buss & Durkee, 1957)

The BDHI consists of 66 true/false items with seven subscales: assault, indirect hostility, irritability, negativism, resentment, suspicion, and verbal hostility. Two-week test-retest reliability coefficients for the subscales range from 0.64 to 0.78.

Spielberger Anger Expression Scale (AX) (Spielberger, Jacobs, Russel, & Crane, 1983)

The AX scale is a 20-item Likert scale with two subscales: Anger-In and Anger-Out. Anger-In measures suppressed or inwardly directed anger; Anger-Out indicates the tendency to express anger toward other persons or the environment. Studies have supported the instrument’s concurrent, convergent and divergent validity; alpha coefficents range from 0.73 to 0.84 (Spielberger et al., 1985).

Rotter Interpersonal Trust Scale (Rotter, 1967)

This is a 19-item Likert scale that measures an individual’s generalized expectancy that the promises of others can be relied on. The scale has been found to have an adequate split-half (r = .76) and test-retest (r = .68) reliability and good construct validity.

Re-lived Anger Memory Task

Participants were asked to recall and then later re-live a specific past experience of anger (Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991). Complete instructions and the videotape are available upon request. To identify a specific anger memory, participants were asked to recall a time when they felt really angry, frustrated, or upset with another person, and were not happy with the outcome. When a participant indicated retrieving a memory, the experimenter then asked: “What happened? Tell me everything about that day – time, place, weather, etc. How were you feeling then? What did you say? What did the other person say? What led up to this? How did the other person respond to the incident? Have you had any contact with that person since? Why do you feel that the situation remains unresolved?” After the participant provided details about the selected memory, the experimenter provided the following instructions: “Later in this session, you will be guided by what you see on the TV. Written instructions on the TV will tell you when the session begins and what you should do when. At one point during the videotape, you will receive instructions to relive that angry situation that we talked about earlier today. The time when you were really angry with … (fill in detail). At other times during the tape, you’ll be asked to just relax and think about nothing in particular. These periods only last for two or three minutes, so please be patient with them. The purpose of these rest periods is to get some baseline measures of your heart rate and blood pressure; thus, we are collecting some very important data even though it seems you are not doing anything. When the session is over, the TV will say so. When the time comes when you are to relive the angry situation that we talked about, the written instructions will say, “Now we want you to think about that time when you felt so angry you wanted to explode.” Relive this situation in your mind by thinking about it and reliving it in your mind. When you are able to feel your anger, please raise your left finger like this. Do you have any questions? Please do not speak during the video. O.K., let’s begin.”

Cardiovascular Measures

An Ohmeda Finapres Blood Pressure Monitor (Model 2300) was used to collect continuous measures of finger arterial pressure and HR. The Finapres self-regulating finger cuff was attached to the middle phalange of the middle finger of the participant’s nondominant hand. A sling was used to immobilize the participant’s arm at heart level. Beat-by-beat measures of HR, SBP and DBP were recorded on a microcomputer through a serial interface using custom software. These data were later converted from beat-by-beat data into a real time metric (Graham, 1978). The Finapres estimates heart rate from fingertip pulse readings, which, though less accurate in the time domain than estimating heart rate from the ECG, is a trivial difference in accuracy over the time periods assessed in this study. In a review of 43 studies evaluating the accuracy of the Finapres technology, Finapres accuracy and precision were concluded to be sufficient for reliable tracking of changes in blood pressure and heart rate (Imholtz, Wieling, van Montfrans, & Wesseling, 1998).

Anger Recall Procedure

All participants were tested individually at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in a laboratory setting. The laboratory session lasted approximately 45 minutes. Informed consent had already been obtained during the initial diagnostic assessment and questionnaire completion. The experimenter attached the blood pressure finger cuff as indicated above. Cardiovascular measures were obtained for a 10-minute initial resting baseline phase in which participants were instructed to sit quietly in the chair. Following this 10-minute baseline, the stimulus videotape without sound was started. The first instructions appeared as follows: “The first session will begin now. We want you to relax for a few minutes. Please continue to look at the X on the screen while you are relaxing. Begin to relax now. Clear your mind. Don’t think about anything in particular.” Then a large X appeared on the screen for two minutes, during which time a pre-anger baseline was collected. Next, instructions to begin recalling the self-chosen anger memory appeared on screen: participants were asked to think about the time they felt so angry they wanted to explode, and to raise a finger when they began to feel their anger. The experimenter paused the stimulus tape on this instruction screen, and the participants’ finger raise served as the cue to restart it. Twenty seconds after participants indicated feeling anger (with the finger raise), a 90-second-long clip of ocean waves began. This provided the external cue for participants to stop re-living their anger. The ocean waves clip was followed by a blank screen, lasting for 150 seconds, which served as the extended recovery period. There were no explicit instructions for the participants during the ocean wave clip or blank screen. This ended the stimulus videotape and participants next provided ratings of anger and anxiety while they were recalling their anger memory on eleven -point Likert scales (0 = least angry or anxious, 10 = most angry or anxious; (Ekman, Friesen, & Ancoli, 1980).

Anger situations were coded independently by two raters for content type, including whether they were trauma-related (i.e., represented a traumatic event) or other-related. Agreement between two raters was 98%. Five percent were rated as trauma-related1, and 95% were rated as other. Examples of trauma-related anger situations were “sexual harassment by my boss” and “physical abuse, almost killed her.” Examples of non-trauma-related anger situations were “my boyfriend stole my furniture,” “argument with my parents,” “my mother hung up the phone on me,” and “my daughter forget her social security card when we went to get her driver’s license.”

Data Reduction and Analytic Strategy

Following previous work with mixed-gender community samples (Barefoot et al., 1993; Brummett et al., 1998) and male veterans (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002), the three subscales of the Cook-Medley Hostility Scale, the seven subscales of the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory, the two subscales of the Spielberger Anger Expression Scale, and the Rotter Interpersonal Trust Scale underwent a principal component analysis with varimax rotation to determine factors associated with hostility. As in previous studies, three factors emerged, accounting for 66% of the total variance. ‘Hostile Beliefs’, the first factor, explained 45% of the variance. It measured cognitive aspects of hostility (cynicism, suspiciousness, resentment); the scales loading above .50 on this factor were the Cook-Medley Cynicism Scale, the Buss-Durkee Suspicion and Resentment Scales, and the Rotter Interpersonal Trust Inventory (negatively correlated). The second factor, ‘Overt Hostility’ (13% of the variance) involved the tendency to express anger towards others; scales loading above .50 were the Buss-Durkee Verbal Scale and Assault Scale, Spielberger Anger-out, and the Cook-Medley Aggressive Responding Scale. The third factor, ‘Covert Hostility’, (8% of the variance) measured the tendency to withhold anger and harbor resentment; factor loadings above .50 were found for the Buss-Durkee Irritability, Indirect, and Resentment Scales, Spielberger Anger-In, and the Cook-Medley Hostile Affect Scale. The Covert Hostility factor was the factor most similar in content, and the most highly correlated (r=.80), with the first factor obtained from a principal component analysis of these hostility measures completed by a sample of male veterans (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002) in the study the current experiment is attempting to replicate. Thus, the primary analyses presented in this manuscript involve the covert hostility factor. Secondarily, results are presented for parallel analyses with the hostile beliefs and overt hostility factors. Previous research (Barefoot et al., 1993) found women to score more highly than men on the covert hostility factor and found no gender differences on hostile beliefs or overt hostility.

Physiological response during re-lived anger was calculated as the difference between physiological activity during the 20 seconds after participants raised their finger to indicate feeling anger and physiological activity during the two minutes prior to the relived anger task. Anger recovery was calculated as the difference between physiological activity during the 90-second ocean wave video and the two minutes prior to re-lived anger. Multiple regression was used to assess the effects of PTSD status and individual differences in covert hostility on cardiovascular and self-reported responses to anger. The independent variables in each analysis were group status (coded as 0 = Control, 1 = PTSD), the covert hostility factor score, and the Group × Covert Hostility interaction. In each analyses group status was entered first, followed by the covert hostility score, and finally the Group × Covert Hostility interaction term. These analyses were repeated with the Overt Hostility and Hostile Beliefs factors.

The dependent variables were 1) baseline DBP, SBP and HR (the 10-minute initial baseline and the two-minute baseline prior to anger recall, analyzed separately); 2) DBP, SBP, and HR magnitude change and rated anger and anxiety during re-lived anger; and 3) DBP, SBP and HR magnitude change during anger recovery. For each physiological dependent variable, age, cardiac and psychiatric medication, ethnicity, and current smoking status were evaluated as potential covariates using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When one of these potential covariates had a significant effect on the independent variable, it was entered first in the regression model. This strategy is in accord with that recommended by experts in the PTSD field (Keane & Kaloupek, 1997). The identified covariates entered into each model are included in each analysis description. Markers of socioeconomic status (SES) were not used as covariates in between group comparisons as reduced education and SES have been shown to be a sequelae of early trauma and PTSD and are thus confounded with PTSD status (Kulka et al., 1990). A basic tenet of ANCOVA is that the covariate is independent of the primary predictor of interest. When the covariate and predictor are not independent, the regression adjustment may obscure part of the treatment effect or product spurious effects (Miller & Chapman, 2001). Thus, the adjustment for SES would result in biased estimates because some effects attributable to PTSD would be eliminated from the dependent variable (for a discussion see Miller & Chapman, 2001).

Results

Sample Description

Participants reported a mean age of 39 years (range = 19–70). Race/ethnicity was almost equally divided among African-American and Caucasian participants (42% vs. 47%), with other ethnic groups representing 11%, resulting in 53% of the sample being of minority status. Thirty-one percent of participants were married. The sample was primarily community based; 17% of participants were veterans. Mean education level was 15 years, while SES status was middle class based on the Hollingshead Index (Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958). Twenty-six percent of participants were current smokers, while 50% were lifetime (current or former) smokers. Participant demographics and tests of group differences are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information by Group

| PTSD (n = 70) M (SD) or % | Control (n = 50) M (SD) or % | Significant Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.21 (11.85) | 35.60 (11.76) | t(119)=6.59 p=.0115 |

| Education | 14.54 (2.57) | 16.72 (2.84) | t(119)=19.11, p<.0001 |

| Hollingshead | 45.53 (17.34) | 31.10 (14.33) | t(119)=23.26, p <.0001 |

| % Veteran | 24% | 6% | χ2(1)=6.7973, p=0.0091 |

| % Minority | 56% | 50% | NS |

| % Employed | 60% | 94% | χ2(1)=17.6994, p<.0001 |

| % Married | 33% | 28% | NS |

| Hostile Beliefs | 0.25 (0.89) | −0.62 (.0.93) | t(119)=27.29, p<.0001 |

| Overt Hostility | 0.06 (1.07) | −0.10 (0.91) | NS |

| Covert Hostility | 0.20 (0.94) | −0.34 (1.03) | t(119)=9.04 p=.0034 |

| Current PTSD+ | 100% | 0% | |

| Current Major Depression+ | 54% | 0% | |

| Lifetime Major Depression+ | 76% | 0% | |

| Lifetime Abuse or Dependence | 41% | 10% | Χ2(1)=14.19, p=<.0002 |

| Current other anxiety disorder | 46% | 12% | χ2(1)=15.32, p=<.00013 |

| Lifetime other anxiety disorder | 59% | 16% | χ2(1)=21.88 p<.0001 |

| PTSD (n = 70) M (SD) | Control (n = 50) M (SD) | Significant Differences | |

| Lifetime Dysthymia | 13% | 2% | χ2(1)=4.50, p=.0339 |

| Lifetime Eating disorder | 11% | 6% | NS |

| On cardiac effecting medication | 31% | 6% | χ2(1)=11.43, p=.0007 |

| On psychiatric medication | 40% | 0% | χ2(1)=26.09, p<.0001 |

| Current smokers | 33% | 16% | χ2(1)=4.33, p<.0375 |

Note. NS=non-significant

Statistical comparisons were not done for Major Depression and PTSD, as group assignment was based on these diagnoses

Group Differences in Hostility

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for age and race were conducted in order to evaluate group differences in hostility factors. The PTSD group was significantly higher on the hostile beliefs factor, F(1,119) = 26.3, and the covert hostility factor, F(1,119) = 10.7, both p < .001, than the control group. The groups were not significantly different on the overt hostility factor, F < 2.0.

Baseline Physiological Values

Covert Hostility Factor

Means for DBP, SBP and HR for each period by group are presented in Table 2, and Table 3 displays correlations between each variable and covert hostility for the full sample and each group separately. Participant ethnicity was significantly related to all baseline blood pressure variables, and so was included as a covariate in all baseline blood pressure analyses. Neither systolic nor diastolic blood pressure baseline differed as a function of PTSD group (all t < 1.1, p > .30) or covert hostility (all t < 1.9, p > .05) for the 10-minute initial baseline or the two-minute baseline prior to anger recall. For DBP, there was a Group × Covert Hostility interaction for both the initial baseline, t(112) = 2.11, p < .04, and the pre-anger baseline, t(112) = 2.19, p < .04. As can be seen in Table 3, in both cases this interaction indicates that baseline DBP was higher with increased covert hostility for women with PTSD, and baseline DBP was lower with increased covert hostility for the control group. The pattern of data was the same for SBP, though the effects were not statistically significant. Women with PTSD had higher HR than women in the control group during the initial baseline, t(113)= 2.03, and the pre-anger baseline t(113) = 2.15, both p < .05. Neither covert hostility nor its interaction with PTSD group explained significant variance in HR baseline.

Table 2.

Mean Levels (and Standard Deviations) for Cardiovascular Variables for Different Experimental Periods for the PTSD and Control Groups

| Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| PTSD | Control | |

| Initial Baseline | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 70.2 (17.6) | 71.6 (13.2) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 132.6 (22.7) | 132.0 (19.2) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 72.4 (9.5) | 67.9 (9.6)* |

| Pre-Anger Baseline | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 73.0 (18.9) | 73.9 (13.1) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 135.4 (22.6) | 135.9 (0.6) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 71.8 (10.1) | 67.0 (9.2)* |

| Re-lived Anger | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 73.1 (8.3) | 74.4 (13.1) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 136.1 (21.0) | 137.0 (20.1) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 73.8 (10.0) | 70.7 (9.1) |

| Anger Rating (0–10) | 6.0 (2.1) | 4.4 (2.0)* |

| Anxiety Rating (0 – 10) | 4.7 (2.8) | 3.1 (2.2)* |

| Anger Recovery | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 73.4 (18.8) | 74.9 (13.1) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | 134.8 (22.3) | 137.1 (20.3) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 71.8 (9.5) | 66.7 (9.1) |

= groups differ at p < .05

Table 3.

Simple Correlations between Dependent Measures and Covert Hostility for the Full Sample and for Each Group Separately

| Correlations with Covert Hostility | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | PTSD group | Control group | |

| Initial Baseline | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | .06 | .22+ | −.16 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | .04 | .12 | −.10 |

| Heart Rate | .10 | .05 | .05 |

| Pre Anger Baseline | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | .10 | .25* | −.14 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | .04 | .15 | −.08 |

| Heart Rate | .10 | −.03 | .13 |

| Re-lived Anger | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | .01 | −.03 | .08 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | .08 | .01 | .21 |

| Heart Rate | .05 | .26* | −.11 |

| Anger Rating | .16+ | .08 | .07 |

| Anxiety Rating | .07 | .08 | −.15 |

| Anger recovery | |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | .04 | .08 | .04 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | .04 | .08 | .05 |

| Heart Rate | .02 | .24* | −.31* |

Note. The first column of numbers shows correlations between the variable at the left of the column and the covert hostility factor score for the whole sample. In order to interpret interactions between group and hostility, the last two columns provide the correlations between the variable at the left of the column and covert hostility separately for the Control and PTSD groups. The sample size is 117 for the cardiovascular variables (67 for the PTSD group, 50 for the Control group) and 120 for the self-report variables (70 for the PTSD group, 50 for the Control group).

= p < .10,

= p < .05.

Hostile Beliefs and Overt Hostility Factors

Like covert hostility, the hostile beliefs factor was positively correlated with the 10-minute initial DBP baseline only for women with PTSD: For DBP, there was a Group × Hostile Beliefs interaction for the initial baseline, t(112) = 2.54, p < .02. Baseline DBP was significantly correlated with Hostile Beliefs for the PTSD group (r = .26, p < .04) but not for the control group (r = −.10, p = .50). Because the effects of covert hostility and hostile beliefs were so similar, we explored the extent to which these two effects are independent or overlapping by carrying out a regression in which ethnicity (the covariate) and PTSD group were entered in the first, followed by the covert hostility score and the hostile beliefs score; finally the Group × Covert Hostility and Group × Hostile Beliefs interactions were entered. As can be seen in Table 4, ethnicity and the interactions of covert hostility and hostile beliefs with PTSD group all independently explained significant amounts of variance in baseline DBP. The entire model explained 16.5% of the variance in baseline DBP (F(6,110) = 3.62, p < .003, R2 = .165).

Table 4.

Regression Table for Prediction of Baseline Diastolic Blood Pressure from Ethnicity, PTSD Group, Covert Hostility, Hostile Beliefs, and Interactions

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | B | Std. Error | Beta | T(110) | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 63.601 | 3.404 | 18.682 | .000 | |

| PTSD Group | −.654 | 3.400 | −.020 | −.192 | .848 |

| Ethnicity | 9.163 | 3.049 | .288 | 3.005 | .003 |

| Hostile Beliefs | −4.567 | 2.519 | −.288 | −1.813 | .073 |

| Covert Hostility | −1.867 | 2.156 | −.120 | −.866 | .389 |

| PTSD Group × Hostile Beliefs interaction | 9.074 | 3.206 | .392 | 2.831 | .006 |

| PTSD Group × Covert Hostility interaction | 7.168 | 2.882 | .330 | 2.487 | .014 |

Note. PTSD Group is coded as 1 = PTSD, 0 = Control; Ethnicity is coded as 0 = white, 1 = other.

Baseline heart rate was significantly and positively correlated with overt hostility for the PTSD group but not significantly correlated for the control group, Group × Overt Hostility t(1.93) = p = .056 for the 10-minute baseline and t(113) = 2.31, p < .03 for the two-minute pre-anger baseline. No other significant relationships were found between either hostile beliefs or overt hostility and any of the baseline cardiovascular measures.

Anger Response

Cardiovascular Response to Re-lived Anger

As we found previously for male combat veterans, covert hostility moderated the relationship between PTSD status and cardiovascular response to anger, Group × Covert Hostility, t(113) = 2.08, p < .05 for HR. As can be seen in Table 3, for women with PTSD there is a significant positive correlation between covert hostility and HR response to anger, whereas for the control group there is a nonsignificant negative correlation between covert hostility and HR response to anger. Thus, greater covert hostility is associated with greater HR response to anger only for women with PTSD. Women with PTSD had less HR increase during anger recall than women in the control group, t(113) = −2.00, p < .05; however, this appears to be due to an initial values difference at baseline: when the two-minute pre-anger HR baseline is covaried out, this effect is no longer significant, t(112) = −1.42, p = .158. For both SBP and DBP, participant ethnicity was significantly related to blood pressure change during anger and so was included as a covariate in the analyses. Other than ethnicity, no variable in the model explained a significant amount of variance in SBP or DBP, all p > .20. Hostile beliefs and overt hostility were not related to DBP, SBP, or HR anger response.

Self-reported Anger and Anxiety to Re-lived Anger

Women with PTSD reported greater anger, t(114) = 3.56, p < .001, and anxiety, t(114) = 3.14, p < .01, to re-lived anger compared with the control group (see Table 2). Covert hostility was not related to anger or anxiety ratings. Hostile beliefs was positively related to both self-reported anger, t(115) = 2.28, p < .03, and anxiety, t(115) = 3.23, p < .002, during re-lived anger. These effects were found for the entire sample; that is, hostile beliefs did not interact with PTSD group.

Cardiovascular Recovery from Re-lived Anger

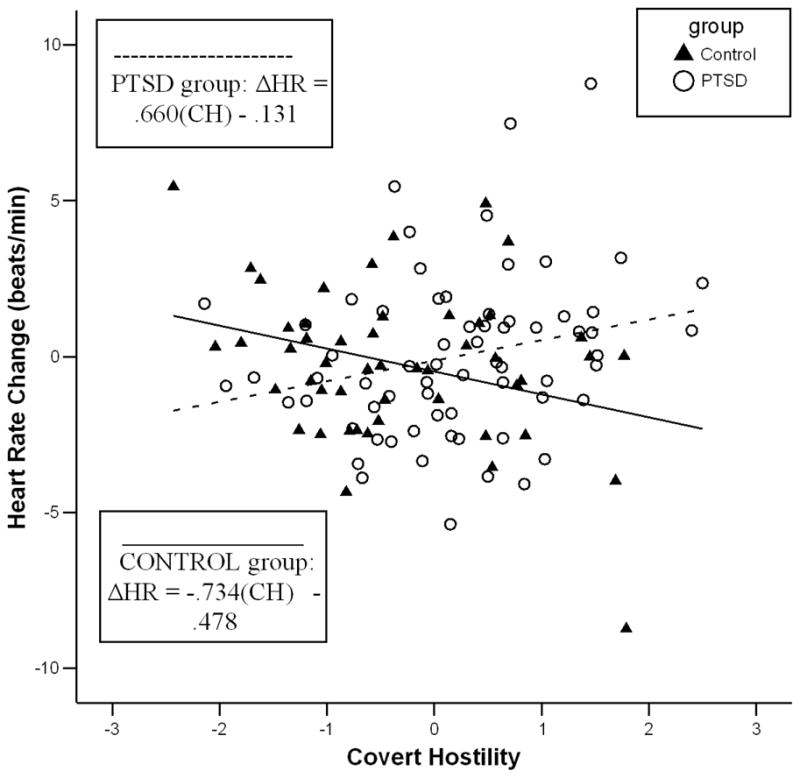

For HR recovery following anger recall, a significant main effect of covert hostility, t(113) = 2.14, p < .04, and a significant Group × Covert Hostility interaction, t(113) = 2.98, p < .004, were found. The main effect of covert hostility cannot be interpreted, however, because the zero-order correlation between covert hostility and HR recovery for the full sample is r =.02 (see Table 3). Examining the zero-order correlations between covert hostility and HR recovery within each group shows the nature of the interaction: there is a significant positive correlation between covert hostility and HR recovery for women with PTSD, r =.24, p < .05, indicating less HR recovery with higher levels of covert hostility, and a significant negative correlation between covert hostility and HR recovery for women in the control group, r = −.31, p < .03, indicating greater HR recovery with higher levels of covert hostility. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 1. Neither PTSD status, covert hostility, nor their interaction was related to SBP or DBP during recovery from relived anger, all p > .20. The models employing the hostile beliefs and overt hostility factors did not explain a significant amount of variance in DBP, SBP, or HR recovery from anger recall.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot depicting heart rate recovery (as the difference between HR during the 90-second ocean wave video and the two minutes prior to re-lived anger) in beats/minute as a function of each participant’s score on the covert hostility factor. Regression lines, and the regression equation for each group are also shown in the Figure. “CH” in each regression equation indicates the covert hostility factor score.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to determine if the relationship between covert hostility and cardiovascular responding in anger recall and anger recovery found among male combat veterans with PTSD (Beckham, Vrana, et al., 2002) is also found in women with PTSD. In the earlier study greater increases in blood pressure during anger recall and recovery were associated with higher levels of covert hostility in male veterans with PTSD, but not in male veterans without PTSD. The lack of effect in the non-PTSD group was contrary to the literature finding a positive relationship between hostility and cardiovascular functioning in non-selected samples (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2000; Suarez, Kuhn, Schanberg, Williams, & Zimmering, 1998), and was interpreted as suggesting that veterans with significant combat experience who do not develop PTSD may possess an unusual ability to modulate negative emotions like fear and anger.

The current study employed the same procedures but a very different sample—compared to the men, the women in this study were younger, mostly non-veterans, and had experienced a variety of traumatic events leading to PTSD. Despite these differences, we replicated the association of cardiovascular response with covert hostility only in participants with PTSD: HR increases during relived anger and recovery from anger were positively correlated with covert hostility in women with PTSD, but not for women in the control group. The results were found for HR, and not blood pressure as was the case for men.

On the other hand, covert hostility moderated the relationship between PTSD status and baseline blood pressure in women: women with PTSD exhibited increased baseline DBP with increased covert hostility, whereas women without PTSD exhibited a non-significant trend toward decreased baseline DBP with increased covert hostility. The lack of a relationship between covert hostility and baseline blood pressure in women without PTSD may, like the reactivity findings described above, be ascribed to effective emotion regulation ability among those who experience traumatic events but do not develop PTSD. It is notable that in our male sample there were no relationships between covert hostility and baseline cardiovascular activity (DBP, SBP, or HR). Previous literature has found a relationship between hostility and ambulatory blood pressure among women but not men (Durel et al., 1989). These results suggest that the effect of covert hostility on blood pressure is more chronic and corrosive in women than in men with PTSD.

In contrast to covert hostility, the hostile beliefs and overt hostility factors were not related to cardiovascular response to anger; however, these factors were related to baseline BP and self-reported affect during anger recall. In particular, the hostile beliefs factor exhibited the same relationship with baseline DBP as did covert hostility: increased hostile beliefs were associated with higher DBP in women with PTSD, but not in the control group. The covert hostility and hostile beliefs factors are independent (r = .012) and follow-up analyses (see Table 4) found independent and robust effects of these two factors interacting with PTSD. These results have important implications for cardiovascular health. Using the unstandardized beta weights from Table 4, it can be seen that a woman with PTSD and factor scores of one on the hostile beliefs factor and one on the covert hostility factor (i.e., one SD above the mean on each factor) is predicted to have a baseline DBP that is 15.6 mm/Hg higher than a woman with similarly high hostility scores on both factors who does not suffer from PTSD. Underscoring the moderating effect of PTSD on this relationship, a woman with PTSD and hostile beliefs and covert hostility factor scores of one is predicted to have a baseline DBP 9–10 mm/Hg higher than a woman with a score of zero (i.e., at the mean) on each of these two hostility factors, regardless of whether or not she suffers from PTSD. Since women with PTSD have significantly higher means on these two hostility factors compared to women without PTSD (see Table 1), having PTSD represents a seriously compounded risk factor: a woman with PTSD is likely to show characteristics of cynicism, resentment, and the tendency to withhold anger, and if she does she will be at significantly increased risk for hypertension.

In general, the measures of hostility were not related to the dependent measures in the sample as a whole; it was only within the women with PTSD that relationships were found. One exception was that women with high levels of hostile beliefs reported more anger and anxiety in response to the recalled anger scenario. Finding that increased hostile beliefs is related to greater report of anger is neither unusual nor unexpected; the fact that this relationship is found for anxiety as well is most likely due to consistently high correlation between similarly-valent affective reports (Russell & Mehrabian, 1977).

PTSD diagnostic status was independently related to two notable outcomes. First, women with PTSD had higher baseline HR, but not higher baseline BP, compared to women without PTSD. These HR and BP findings are consistent with meta-analytic results, based primarily on data from male combat veterans (Pole, 2007), though our own data from male combat veterans, which were included in this meta-analysis, found no baseline HR or BP effects of PTSD status (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002). Second, women with PTSD reported greater anger and anxiety in response to the recalled anger scenario than did women without PTSD, replicating our own findings among male combat veterans with and without PTSD (Beckham, Vrana et al., 2002).

The current data have important implications for the relationship between PTSD and health outcomes. A growing literature is documenting that posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with poorer health outcomes. Individuals with PTSD have more health complaints, physician-diagnosed medical conditions (Beckham et al., 1998), and health care utilization (Calhoun, Bosworth, Grambow, Dudley, & Beckham, 2002). Chronic PTSD has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Flood et al., 2009; Schnurr & Green, 2004). An epidemiological study of veterans 30 years after military service found that PTSD was associated with increased mortality for all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and external causes of death (Boscarino, 2006). A recent prospective study (Kubzansky, Koenen, Spiro, Vokonas, & Sparrow, 2007) found that for each standard deviation increase in PTSD symptom level, men with PTSD had age-adjusted relative risks of 1.26 (CI, 1.05–1.51) for all cardiovascular heart disease (CHD) outcomes combined (nonfatal myocardial infarction, fatal CHD, and angina).

There are many potential mechanisms through which poor health is connected to PTSD. For example, PTSD veterans smoke more (Beckham, 1999), have higher lipids (Calhoun, Wiley, Dennis, & Beckham, 2009), report poorer objective sleep (Calhoun et al., 2007), and report more daily negative affect (Beckham et al., 2005; Beckham, Gehrman, McClernon, Collie, & Feldman, 2004; Beckham, Moore, & Reynolds, 2000). However, the current results strongly suggest that the relationship between PTSD and poor cardiovascular health outcomes (e.g., HR, BP) is substantially moderated by hostility, and especially covert hostility. Over the past decade, increasing evidence suggests that anger and hostility are characteristic of individuals with PTSD (Becker et al., 2007; Beckham, Calhoun et al., 2002; Orth & Wieland, 2006). PTSD veterans with higher levels of hostility are to more likely to die prematurely than veterans without PTSD and more likely to die from cardiovascular related causes (Flood et al., 2009). The large majority of the literature on the relationship between PTSD and health, and on the relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular response, is based on data from male combat veterans. The current study finds that the relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular responses of heart rate and blood pressure, moderated by covert hostility, is the same for women as it is for men, and the effect may be even more robust for women.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Office of Research and Development Clinical Science, Department of Veterans Affairs, R01MH062482, K24DA016388, 2R01CA081595, and R21DA019704. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Six percent of the women in the PTSD group described anger situations that were trauma-related and two percent of the women in the control group described anger situations that were trauma-related. Removing these subjects from the analyses did not influence the results.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barefoot JC, Beckham JC, Haney TL, Siegler I, Lipkus IM. Age differences in hostility among middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1993;3:3–9. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barefoot JC, Larsen S, Lieth LVD, Schroll M. Hostility, incidence of acute myocardial infarction, and mortality in a sample of older Danish men and women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:477–484. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker ME, Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Dennis MF, Bukenya DS, Beckham JC. A placebo-controlled trial of Bupropion SR in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;27:193–197. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318032eaed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC. Smoking and anxiety in combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1999;31:103–110. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1999.10471731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Calhoun PS, Glenn DM, Barefoot JC. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, hostility, and health in women: A review of current research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:219–228. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Feldman ME, Barefoot JC, Fairbank JA, Helms MJ, Haney TL, et al. Ambulatory cardiovascular activity in Vietnam combat veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:269–276. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Feldman ME, Vrana SR, Mozley SL, Erkanli A, Clancy CP, et al. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking in smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary study. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;13:218–228. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Flood AM, Dennis MF, Calhoun PS. Ambulatory cardiac activity and hostility ratings in women with chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Gehrman PR, McClernon FJ, Collie CF, Feldman ME. Cigarette smoking, ambulatory cardiovascular monitoring and mood in Vietnam veterans with and without chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1579–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Kirby AC, Fairbank JA. Health status, somatization, and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1565–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Moore SD, Reynolds V. Interpersonal hostility and violence in Vietnam combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of theoretical models and empirical evidence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5:451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Vrana SR, Barefoot JC, Feldman ME, Fairbank JA, Moore SM. Magnitude and duration of cardiovascular responses to anger in Vietnam veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:228–234. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a clinician-administered posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and mortality among U.S. Army veterans 30 years after military service. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummett BH, Maynard KE, Babyak MA, Haney TL, Siegler IC, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC. Measures of hostility as predictors of facial affect during social interaction: Evidence for construct validity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:168–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02884957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;42:155–162. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, Beckham JC. Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:2081–2086. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Wiley M, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Self-reported health and physician diagnosed illnesses in women with posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:122–130. doi: 10.1002/jts.20400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Wiley M, Dennis MF, Means MK, Edinger JD, Beckham JC. Objective evidence of sleep disturbance in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:1009–1018. doi: 10.1002/jts.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durel LA, Carver CS, Spitzer SB, Llabre MM, Weintraub JK, Saab PG, Schneiderman N. Associations of blood pressure with self-report measures of anger and hostility among Black and White men and women. Health Psychology. 1989;8:557–575. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV, Ancoli S. Facial signs of emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Flood AM, Boyle SH, Calhoun PS, Dennis MF, Moore SD, Barefoot JC, et al. Prospective study of externalizing and internalizing subtypes of posttraumatic stress disorder and their relationship to mortality among Vietnam veterans. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.08.002. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Maynard KE, Helms MJ, Haney TL, Siegler IC, Barefoot JC. Hostility predicts magnitude and duration of blood pressure response to anger. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;23:229–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596208324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. Constraints on measuring heart rate and period sequentially through real and cardiac time. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:492–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SG, Feinleib M, Kannel WB. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham Study. III. eight-year incidence of coronary heart disease. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1980;111:37–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB, Redlich RL. Social class and mental illness. New York: John Wiley; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imholtz B, Wieling W, van Montfrans G, Wesseling K. Fifteen years experience with finger arterial pressure monitoring: assessment of the technology. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;38:605–616. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius S. Sympathetic hyperactivity and coronary risk in hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:886–893. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Kaloupek DG. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in PTSD: Implications for research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;821:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS, Olson SB, Francis JL, Phankao C, Merz CNB, Sopko G, et al. Anger, hostility, and cardiac symptoms in women with suspected coronary artery disease: The women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) study. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:1214–1223. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64:109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, et al. Trauma and the Vietnam War generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Carstensen LL, Friesen WV, Ekman P. Emotion, physiology, and expression in old age. Psychology and Aging. 1991;6:28–35. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Owens JF, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Jansen-McWilliams L. Are hostility and anxiety associated with carotid artherosclerosis in health postmenopausal women? Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:633–638. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GM, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, Gersons BPR. Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Wieland E. Anger, hostility and posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:698–706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N. The psychophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:725–746. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality. 1967;35:651–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Mehrabian A. Evidence for a three-factor theory of emotions. Journal of Research in Personality. 1977;11:273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Jacobs G, Russell S, Crane R. Assessment of anger: The State-Trait Anger Scale. In: Butcher JN, Spielberger CD, editors. Advances in personality assessment. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Johnson EH, Russell SF, Crane RJ, Jacobs A, Worden TJ. The experience and expression of an anger expression scale. In: Chesney MA, Rosenman RH, editors. Anger and hostility in cardiovascular and behavioral disorders. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985. pp. 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Zimmering EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JE, Paton CC, Siegler IC, Eigenbrodt ML, Nieto FJ, Tyroler HA. Anger proneness predicts coronary heart disease risk: prospective analysis from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2000;101:2034–2039. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]