Abstract

A polymer blend consisting of antimicrobials (chlorhexidine, clindamycin, and minocycline) physically admixed at 10% by weight into a salicylic acid-based poly (anhydride-ester) (SA-based PAE) was developed as an adjunct treatment for periodontal disease. The SA-based PAE/antimicrobial blends were characterized by multiple methods, including contact angle measurements and differential scanning calorimetry. Static contact angle measurements showed no significant differences in hydrophobicity between the polymer and antimicrobial matrix surfaces. Notable decreases in the polymer glass transition temperature (Tg) and the antimicrobials' melting points (Tm) were observed indicating that the antimicrobials act as plasticizers within the polymer matrix. In vitro drug release of salicylic acid from the polymer matrix and for each physically admixed antimicrobial was concurrently monitored by high pressure liquid chromatography during the course of polymer degradation and erosion. Although the polymer/antimicrobial blends were immiscible, the initial 24 h of drug release correlated to the erosion profiles. The SA-based PAE/antimicrobial blends are being investigated as an improvement on current localized drug therapies used to treat periodontal disease.

Keywords: biodegradable polymer, polymer blends, salicylic acid, antimicrobials

Introduction

Polyanhydrides have been studied by many researchers over the past 2 decades as drug carriers.1–3 Particularly, polyanhydrides exhibit nearly zero-order drug release profiles in vitro2,3 because they primarily erode by a surface erosion mechanism that excludes water from the polymer matrix during degradation.4–7 Polyanhydride matrices have been examined for the delivery of multiple bioactive agents, such as hydrophobic drugs, anticancer agents, and DNA.8–11

Building upon the success of the polyanhydrides, our laboratory synthesized salicylic acid-based poly (anhydride-ester) (SA-based PAEs)12–14 that degrade into active drug molecules and may also act as drug carrier matrices. Salicylic acid is particularly relevant because it is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that can treat the inflammation and pain associated with periodontal disease.15,16 In an early example, the SA-based PAEs were fabricated into fibers, and then the degradation and mechanical properties examined.17 On the basis of our early results, we evaluated the SA-based PAEs as drug delivery systems to concurrently deliver physically admixed antimicrobials and chemically incorporated salicylic acid both of which are released upon hydrolytic degradation of the polymer matrix.18 The combined delivery of an antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory is of particular interest for treating periodontal disease.

Periodontal disease is a very common bacterial infection that causes the periodontium (gum tissue) and bone surrounding the teeth to erode and resorb, ultimately causing tooth loss.19 Typically, periodontal disease is treated with scaling and root planing to physically remove plaque below the gum line. Scaling and root planing is usually followed with additional treatments, including systemic administration of antibiotics to ensure bacterial destruction.20 Recent therapies include localized delivery of antibiotics to reduce the risk of adverse systemic drug reactions and to decrease concerns of patient compliance.21–24 Examples of such commercially available products include Arestin®, a microsphere system based on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) for minocycline release and Atridox®, a poly(lactic acid) (PLA)-based system for doxycycline release. Notably, the current approach to localized delivery utilizes PLGA and PLA, which have been shown to cause inflammation and a foreign body response.25 In comparison, the SA-based PAEs in this article do not cause inflammation, whereas the PLA-based systems show pronounced inflammation in a rat defect model.26 Nonetheless, the PLA and PLGA systems enable a prolonged release of the antimicrobials over 1–3 weeks without a lag phase rather than immediate release of the antibiotic without polymer. The polymer/antimicrobial system described herein is designed for implantation into the pockets formed in the periodontium (gum tissue) such that both the NSAID and antimicrobials are simultaneously and locally released into the periodontal pocket.

Three antimicrobials (chlorhexidine·2HCl, clindamycin·HCl, and minocycline·HCl) were physically admixed into the polymer matrix at 10 wt % at approximately the current therapeutic levels used in similar periodontal products.23,27–29 The antimicrobials have different octanol/water partition coefficient (log P)30 and pKa31 values, which correlate to each drug's hydrophobicity and charge (Table I) and thus, their potential release rate from the biodegradable polymer matrix. Further, the three antimicrobials provide a range of options to prevent contraindications in patients who are clinically relevant and have been examined for their potential use in other delivery systems throughout the literature.19,27,32–34

Table I. LogP, pKa, Solubility, Tm, and Td Values of Antimicrobial Agents and Salicylic Acid.

This article describes the physical polymer degradation characteristics and the controlled, concurrent in vitro release of clinically relevant antimicrobials and a NSAID from a biodegradable polymer matrix. The localized drug delivery system described herein may enhance the benefits of localized antimicrobial delivery systems by providing localized pain relief and anti-inflammatory effects due to the concurrent release of an NSAID,27 in addition to the release of antimicrobials to reduce microbial growth.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Poly[1,6-bis(o-carboxyphenoxy)hexanoate] was prepared using previously described methods.13,14 The polymer had Mw = 20,600, PDI = 1.2, and Tg = 65°C. Chlorhexidine·2HCl, clindamycin·HCl, and minocycline·HCl were purchased from MP Biomedicals (Irvin, CA) and used as received. Potassium phosphate dibasic and potassium phosphate monobasic and high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade-acetonitrile were obtained from Aldrich.

Polymer disk preparation

The antimicrobials were separately incorporated into the polymer at 10% (w/w). Polymer (900 mg) was heated in a 150 mL PTFE beaker (FisherBrand, Pittsburg, PA) with a heat gun for ∼2 min or until the polymer began to flow at 65°C. Each antimicrobial agent (100 mg) was added to the molten polymer and stirred for 1 min with a glass stirring rod. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature and then ground for 30 s in a coffee grinder (Mr. Coffee, Rye, NY).

The ground antimicrobial-polymer mixture (50.0 ± 5.0 mg) was placed into an IR pellet die (International Crystal Laboratories, Garfield, NJ) and pressed at 4,000 psi at room temperature for 5 min in a Carver Press (Carver, Wabash, IN). The resulting disks were 6.0 ± 0.2 mm diameter and 1.0 ± 0.2 mm thick as determined by vernier caliper measurements (Mitutoyo, Japan).

Differential scanning calorimetry studies

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on polymer/antimicrobial samples in triplicate following admixing but prior to pressing into disks. Up to 15 mg of each sample was placed in a TA instruments aluminum hermetic pan and analyzed on a TA Instruments Q200 DSC (New Castle, DE). The samples were tested using a heat- cool- heat scan from 0 to 200°C at 10°C/min under N2. The polymer's Tg values were obtained from the second heat cycle and determined as the inflection point for all samples. Each antimicrobial's Tm was obtained from the first heat cycle. All DSC data analysis was completed using TA Universal Analysis software on a Dell Dimension 3000 computer with a Windows XP operating system.

Contact angle measurements

Static contact angle measurements were performed on polymer samples in triplicate on three separate samples prior to degradation using deionized water on a model 100 goniometer (Rame-Hart, Mountain Lakes, NJ). The contact angle was determined digitally with a camera attachment and the measuring system on the DROPimage Advanced software on a Dell Dimension 3000 computer with a Windows XP operating system.

In vitro degradation studies

The sample disks (40.0 ± 1.4 mg) were placed in 20-mL scintillation vials containing 10 mL 0.1M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) at pH 7.4. The vials were stored in a New Brunswick Scientific Series 25 controlled environment incubator shaker at 37°C and constantly shaken at 65 rpm. The degradation media was decanted from the vial and replaced with 10-mL fresh PBS at predetermined time intervals. The spent degradation media was stored at room temperature until further analysis. The degradation study was conducted twice with an n = 3 for both sets of experiments. All data shown are the average of at least three samples.

Determination of sample mass loss and water uptake

Water uptake and mass loss were determined by obtaining the mass of each sample using an analytical balance (Mettler Toledo Columbus, OH). At predetermined time points during the degradation study, the samples were removed from the degradation media, rinsed in deionized water to remove residual phosphate salts, and patted with Kimwipes® (Kimberly-Clark, Neenah, WI). Each sample was lyophilized in a Freezone Freeze Dry System (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) for 48 h to ensure a constant mass. The water uptake was calculated using Eq. (1)7,35:

| (1) |

where WA is water absorbed by the sample or water uptake, Wh is the mass of the hydrated sample, and Wr is the residual mass of the lyophilized sample. The mass loss was calculated using Eq. (2)7,35:

| (2) |

where ML is the mass loss of the sample and W0 is the mass of the sample prior to degradation. Three samples were measured and averaged for each time point (n = 3).

High pressure liquid chromatography analysis of degradation media

Free salicylic acid release and antimicrobial (chlorhexidine·2HCl, minocycline·HCl, and clindamycin·HCl) release were quantified using a Gemini C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) on a Perkin Elmer (PE) HPLC system consisting of a Series 200 UV detector, a Series 200 pump, and an ISS 200 autosampler. The HPLC system was connected to a Dell computer running PE TotalChrom software via PE-Nelson 900 Interface and 600 LINK. Samples were diluted using PBS if needed to ensure measurements within the calibration curve and filtered through 0.45 μm poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) syringe filters (Nalgene, Rochester, NY). Salicylic acid release was monitored at 210 nm, while chlorhexidine, clindamycin, and minocycline were monitored at 254, 210, and 298 nm, respectively. The mobile phase was 75% 20 mM dibasic and monobasic potassium phosphate at pH 2.5 using 1N HCl to adjust the pH and 25% acetonitrile. Five point calibration curves were generated for each compound with concentrations ranging between 0.0025 mg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL. Complete recovery (100 wt % of incorporated antimicrobials) of the antimicrobials was ensured by dissolving any remaining solid at the end of the in vitro degradation study and running the dissolved samples on the HPLC with the same running conditions.

Results and Discussion

Influence of admixed antimicrobials on polymer matrix properties

The incorporation of molecules into a polymer's matrix may alter the inherent properties of the matrix. Static contact angle and DSC measurements were performed to determine the effect of the admixed antimicrobials on polymer 1 (Fig. 1) properties.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of poly[1,6-bis(o-carboxyphenoxy)hexanoate] (Polymer 1).

Primarily, the static contact angle was used to identify any changes to the hydrophobic nature of the polymer surface. Compression-molded disks of the SA-based PAE alone showed a static contact angle of 56° in deionized water. The contact angles decreased slightly to 54° when the antimicrobials were added to the compression-molded polymer at 10 wt %. Based on the minimal change in the contact angle measurement, the antimicrobials are not influencing the hydrophobic surface of polymer 1.

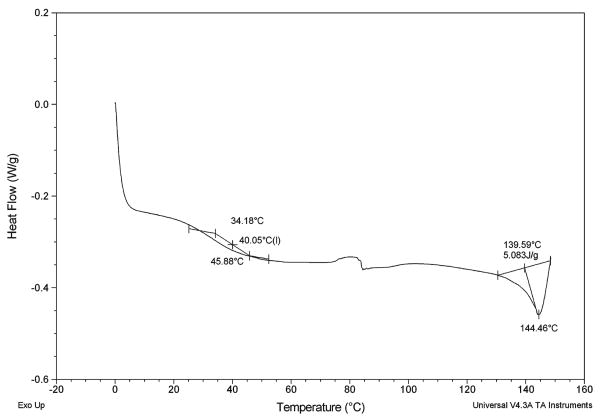

DSC measurements were conducted to determine the extent of mixing between the antimicrobials and the polymer chains through changes in the glass transition temperature of polymer 1. DSC has been used for decades as a method to measure the interaction or mixing of drugs within polymeric matrix systems.36 The DSC results are summarized in Table II. The Tg of the polymer alone is 65°C, and a noticeable decrease in the polymer Tg is observed with each antimicrobial admixture. For the admixtures, the polymer's glass transition (39–65°C) is clearly separated from the antimicrobials' melting transition (138–152°C). A sample DSC curve for clindamycin is displayed in Figure 2. Additionally, a significant decrease in the Tm of chlorhexidine was observed from 187°C for chlorhexidine alone to 152°C in the chlorhexidine/polymer blend. The DSC results show that there is a characteristic lowering of the polymer's Tg for each of the polymer/antimicrobial blends that is consistent with previously reported results on diffusion-controlled drug release from polymers.37 Each of the antimicrobials acts as a plasticizer within the polymer matrix, which indicates an increase in the free volume of the polymer.

Table II. Thermal Properties of Antimicrobial: Polymer Blends.

| Sample | Polymer Tg (°C) | Antimicrobial Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer | 65 | * |

| 10% Chlorhexidine in Polymer | 54 | 152 |

| 10% Clindamycin in Polymer | 40 | 144 |

| 10% Minocycline in Polymer | 39 | 138 |

Thermal transition was not observed.

Figure 2.

Representative DSC curve of 10% clindamycin HCl in SA-based adipic PAE (polymer Tg shown at 40°C and clindamycin Tm shown at 144°C).

Salicylic acid and antimicrobial release

The retention time of each compound separated by HPLC is shown in Table III; each compound is distinct and clearly separated from salicylic acid (SA). The cumulative release of salicylic acid from the SA-based PAE matrix is shown in Figures 3 and 4 for each of the admixed antimicrobial matrices. Compared to polymer alone, the overall rate of salicylic acid release resulting from hydrolytic degradation of the polymer backbone was not significantly influenced by the presence of each admixed antimicrobial. Even though the differences in the release profiles are not statistically significant, a strong trend is observed: the amount of salicylic acid released into the media decreases with increased antimicrobial hydrophobicity (Table I, Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, all release profiles exhibit a lag phase of ∼15 h. After the lag phase, the release profile is linear, faster, nearly zero-order, and ultimately reaches a plateau. Polymers were 50% degraded (t1/2) at times ranging from 25 h for the polymer alone to 30 h for minocycline (most hydrophilic at log P −0.55), and 42 h for chlorhexidine (most hydrophobic at log P 4.55).

Table III. HPLC Retention Times for Chlorhexidine, Clindamycin, Minocycline, and Salicylic Acid.

| Compound | Retention Time (min) |

|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine | 29.6 |

| Clindamycin | 5.1 |

| Minocycline | 2.3 |

| Salicylic Acid | 8.1 |

Figure 3.

Cumulative release profiles of salicylic acid generated from the four different polymer matrices, ranging from the salicylic acid-based polymer alone to and the three antimicrobials (10 wt %) admixed within the polymer at 140 h.

Figure 4.

Cumulative release profiles of salicylic acid generated from the four different polymer matrices, ranging from the salicylic acid-based polymer alone to and the three antimicrobials (10 wt %) admixed within the polymer at 24 h.

The release profiles of the three admixed antimicrobials from each polymer/antimicrobial matrix are compared in Figures 5 and 6. The antimicrobial release generally corresponds to the log P values: chlorhexidine (log P 4.55) exhibited a longer lag phase and minimal release into the media before the matrix lost its integrity, whereas minocycline (log P −0.55) and clindamycin (log P 1.82) are quickly released into the degradation media. Given the large disparity between more hydrophobic drugs (e.g. chlorhexidine) and the SA-based PAE, the release of drugs with log P values and solubilities equal to or less than that of salicylic acid are better controlled. These studies were conducted using the SA-based PAE with an adipic linker (C = 4), but antimicrobial release may be tailored in the future for use with other SA-based PAEs with different linkers as shown from their varied degradation rates.14

Figure 5.

Cumulative release profiles of admixed antimicrobials from the salicylic acid-based polymer matrices at 140 h.

Figure 6.

Cumulative release profiles of admixed antimicrobials from the salicylic acid-based polymer matrices at 24 h.

Additionally, the pKa values (Table I) for each compound may also influence the release rate. Salicylic acid and minocycline31,38 will be partially deprotonated in PBS (pH 7.4), whereas chlorhexidine and clindamycin will be mostly in the neutral form. Chlorhexidine has a higher pKa value (10.3)31,39 and clindamycin is also basic with a pKa value of 7.6,31,40 thus, both will be mostly neutral at the pH of these experiments.41 Although the hydrophobicity of the drugs has most influence on the drug release rate, ion-pairing may occur between salicylic acid and the basic drugs, chlorhexidine and clindamycin. The mostly neutral minocycline may not interact with the salicylic acid, especially considering its very hydrophilic log P value. Although pKa is likely to influence release rates, the drug release profiles shown in Figures 5 and 6 more clearly correlate to log P, that is, the more hydrophobic drugs are released more slowly.

Mass loss and water uptake

Mass loss and water uptake of the polymer disks were also monitored for the first 24 h of hydrolytic degradation, then compared to the drug release rates to determine how water permeation influences polymer degradation and ultimately drug release. These experiments were limited to 24 h because the shape of the matrix changes and integrity decreases after this time point. The mass loss data are shown in Figure 7, and the water uptake data are shown in Figure 8. The polymer alone has the fastest rate of mass loss; the minocycline and chlorhexidine also have significant mass loss in the first 24 h of degradation. However, clindamycin has very little mass loss, which may be because of the similar log P values of clindamycin (1.82) and salicylic acid (2.06) creating an equilibrium with little driving force for physical degradation of the admixed clindamycin samples. The admixed clindamycin samples had the least amount of mass loss and water uptake and an intermediate release rate. The minocycline admixed samples had the most similar mass loss and water uptake profiles compared to the polymer alone. In general, the presence of admixed antimicrobials slowed down the matrices mass loss and water uptake.

Figure 7.

Percentage of mass loss from the polymer matrices during the degradation study (up to 24 h).

Figure 8.

Percentage water uptake from the polymer matrices during the degradation study (up to 24 h).

The water uptake results (Fig. 8) depict the same trend as the mass loss results (Fig. 7). The polymer alone has the greatest amount of water uptake, followed by the hydrophobic chlorhexidine and hydrophilic minocycline. After 24 h, the minocycline- and chlorhexidine-containing disks absorbed more water than clindamycin-admixed disks. These observations correlate with our salicylic acid release in that salicylic acid release from the polymer alone is fastest, followed by minocycline, chlorhexidine, and clindamycin, respectively (Fig. 4).

Conclusions

Polyanhydrides are often defined as surface-eroding materials4 with tunable erosion mechanisms for tissue engineering and sensitive compounds, such as proteins.42,43 This research sought to correlate drug release rate to polymer matrix erosion profiles based on water uptake and mass loss. The varied solubility parameters and immiscibility of the polymer/antimicrobial blends were observed to influence drug release as demonstrated in related studies.44,45 Most importantly, salicylic acid release profiles were not influenced by the incorporated drugs. The SA-based PAEs release antimicrobials after a 12-h lag phase, which may be more useful than the PLA and PLGA-based systems for sustaining the overall drug release. Typically, drug release from the Arestin® system occurs immediately with drug release percentages at 99% after the first 72 h.46 Upon analysis of the initial 24 h of drug release, the trend for salicylic acid and antimicrobial release correlates with the mass loss and water uptake findings (Figs. 4, 6–8). Based on the results, the release of three antimicrobials may be primarily controlled by drug diffusion from the polymer matrix. The antimicrobials (chlorhexidine·2HCl, clindamycin·HCl, and minocycline·HCl) were successfully admixed into the SA-based PAE matrices and their subsequent release sustained for at least 3 days. The antimicrobial release generally slowed with increasing hydrophobicity of the antimicrobials as based on the log P values. In summary, a range of antimicrobials with varying properties can be released from the SA-based PAE matrices without affecting the chemical degradation of the polymer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mark Reynolds DDS, Ph.D. for insight into relevant antimicrobials, Almudena Prudencio, Ph.D. for initial polymer synthesis, and Kenya Whitaker-Brothers, Ph.D. for preliminary chlorhexidine studies.

Contract grant sponsor: NSF-IGERT: Integratively Engineered Biointerfaces; contract grant number: DGE 33196

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Health; contract grant number: DE 13207

References

- 1.Kumar N, Langer RS, Domb AJ. Polyanhydrides: An overview. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:889–910. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain JP, Modi S, Domb AJ, Kumar N. Role of polyanhydrides as localized drug carriers. J Control Release. 2005;103:541–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhrich K, Cannizzaro S, Langer R, Shakesheff K. Polymeric systems for controlled drug release. Chem Rev. 1999;99:3181–3198. doi: 10.1021/cr940351u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Burkersroda F, Schedl L, Gopferich A. Why degradable polymers undergo surface erosion or bulk erosion. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4221–4231. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gopferich A, Tessmar J. Polyanhydride degradation and erosion. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:911–931. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbari H, D'Emanuele A, Atwood D. Effect of geometry on the erosion characteristics of polyanhydride matrices. Int J Pharm. 1998;160:83–89. doi: 10.3109/10837459809028502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akbari H, D'Emanuele A, Atwood D. Effect of fabrication technique on the erosion characteristics of polyanhydride matrices. Pharm Dev Technol. 1998;3:251–259. doi: 10.3109/10837459809028502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkland C, Kipper MJ, Narasimhan B, Kim K, Pack DW. Microsphere size, precipitation kinetics and drug distribution control drug release from biodegradable polyanhydride microspheres. J Control Release. 2004;94:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shikanov A, Vaisman B, Krasko MY, Nyska A, Domb A. Poly (sebacic acid-co-ricinoleic acid) biodegradable carrier for paclitaxel: In vitro release and in vivo toxicity. J Biomed Mater Res. 2004;69A:47–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quick DJ, Macdonald KK, Anseth KS. Delivering DNA from photocrosslinked, surface eroding polyanhydrides. J Control Release. 2004;97:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brem H. Biodegradable polymer implants to treat brain tumors. J Control Release. 2001;74:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00311-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erdmann L, Uhrich K. Synthesis and degradation characteristics of salicylic acid derived poly(anhydride-esters) Biomaterials. 2000;21:1941–1946. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmeltzer RC, Anastasiou TJ, Uhrich KE. Optimized synthesis of salicylate-based poly(anhydride-esters) Polym Bull. 2003;49:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00289-003-0123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prudencio A, Schmeltzer RC, Uhrich KE. Effect of linker structure on salicylic acid-derived poly(anhydride-esters) Macromolecules. 2005;38:6895–6901. doi: 10.1021/ma048051u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vane JR, Botting RM. Anti-inflammatory drugs and their mechanism of action. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:S78–S87. doi: 10.1007/s000110050284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drouganis A, Hirsh R. Low-dose aspirin therapy and periodontal attachment loss in ex- and non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:38–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitaker-Brothers K, Uhrich K. Poly(anhydride-ester) fibers: Role of copolymer composition on hydrolytic degradation and mechanical properties. J Biomed Mater Res. 2004;70A:309–318. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson ML, Uhrich KE. In vitro release characteristics of antimicrobials admixed into salicylic acid-based poly(anhydride-esters) Polym Mater Sci Eng. 2006;95:979–980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwach-Abdellaoui K, Vivien-Castioni N, Gurny R. Local delivery of antimicrobial agents for the treatment of periodontal diseases. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:83–99. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slots J, Ting M. Systemic antibiotics in the treatment of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2002;28:106–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trombelli L, Tatakis DN. Periodontal diseases: Current and future indications for local antimicrobial therapy. Oral Dis. 2003;9:11–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.9.s1.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killoy WJ, Saiki SM. A new horizon for the dental hygienist: Controlled local delivery of antimicrobials. J Dent Hyg. 1999;73:84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cianco S. Site specific delivery of antimicrobial agents for periodontal disease. Gen Dent. 1999:172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Killoy WJ. The clinical significance of local chemotherapies. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatakis D, Trombelli L. Adverse effects associated with a bioabsorbable guided tissue regeneration device in the treatment of human gingival recession defects. J Periodontol. 1999;70:542–547. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.5.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds M, Prudencio A, Aichelman-Reidy ME, Woodward K, Uhrich KE. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-derived poly(anhydride-esters) in bone and periodontal regeneration. Curr Drug Deliv. 2007;4:1–7. doi: 10.2174/156720107781023866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenwell H, Bissada NF. Emerging concepts in periodontal therapy. Drugs. 2002;62:2581–2587. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200262180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Addy M. Chlorhexidine compared with other locally delivered antimicrobials: A short review. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:957–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz M, Schmoldt A. Therapeutic and toxic blood concentrations of more than 800 drugs and other xenobiotics. Pharmazie. 2003;58:447–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LogP Calculation: SciFinder scholar ACD/Labs Software v8.14 for Solaris; © 1994–2005 ACD/Labs.

- 31.Williams DA, Lemke TL. Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and WIlkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yue IC, Poff J, Cortes ME, Sinisterra RD, Faris CB, Hilden P, Langer R, Shastri VP. A novel polymeric chlorhexidine delivery device for the treatment of periodontal disease. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3743–3750. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker C, Gordon J. The effect of clindamycin on the microbiota associated with refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1990;61:692–698. doi: 10.1902/jop.1990.61.11.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park YJ, Lee JY, Yeom HR, Kim KH, Lee SC, Shim IK, Chung CP, Lee SJ. Injectable polysaccharide microcapsules for prolonged release of minocycline for the treatment of periodontitis. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1761–1766. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitaker-Brothers K, Uhrich K. Investigation into the erosion mechanism of salicylate-based poly(anhydride-esters) J Biomed Mater Res. 2006;76A:470–479. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theeuwes F, Hussain A, Higuchi T. Quantitative analytical method for determination of drugs dispersed in polymers using differential scanning calorimetry. J Pharm Sci. 1974;63:427–429. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600630325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siepmann F, Le Brun V, Siepmann J. Drugs acting as plasticizers in polymeric systems: A quantitative treatment. J Control Release. 2006;115:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colaizzi JL, Klink PR. pH-partition behavior of tetracyclines. J Pharm Sci. 1969;58:1184–1189. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600581003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akaho E, Fukumori Y. Studies on absorption characteristics and mechanism of adsorption of chlorhexidine mainly by carbon black. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:1288–1297. doi: 10.1002/jps.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wan H, Holmen AG, Wang Y, Lindberg W, Englund M, Nagard MB, Thompson RA. High-throughput screening of pKa values of pharmaceuticals by pressure-assisted capillary electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2639–2648. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabath LD, Toftegaard I. Rapid microassays for clindamycin and gentamicin when present together and the effect of ph and of each on the antibacterial activity of the other. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974;6:54–59. doi: 10.1128/aac.6.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burkoth AK, Burdick J, Anseth KS. Surface and bulk modifications to photocrosslinked polyanhydrides to control degradation behavior. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:352–259. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<352::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torres MP, Vogel BM, Narasimhan B, Mallapragada SK. Synthesis and characterization of novel polyanhydrides with tailored erosion mechanisms. J Biomed Mater Res. 2006;76A:102–110. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyu SP, Sparer R, Hobot C, Dang K. Adjusting drug diffusivity using miscible polymer blends. J Control Release. 2005;102:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karavas E, Georgarakis E, Bikiaris D. Adjusting drug release by using miscible polymer blends as effective drug carries. J Therm Anal Cal. 2006;84:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 46.OraPharma. Data on file. Warminster, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]