Abstract

Objectives To describe trends in the numbers of Down’s syndrome live births and antenatal diagnoses in England and Wales from 1989 to 2008.

Design and setting The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register holds details of 26488 antenatal and postnatal diagnoses of Down’s syndrome made by all cytogenetic laboratories in England and Wales since 1989.

Interventions Antenatal screening, diagnosis, and subsequent termination of Down’s syndrome pregnancies.

Main outcome measures The number of live births with Down’s syndrome.

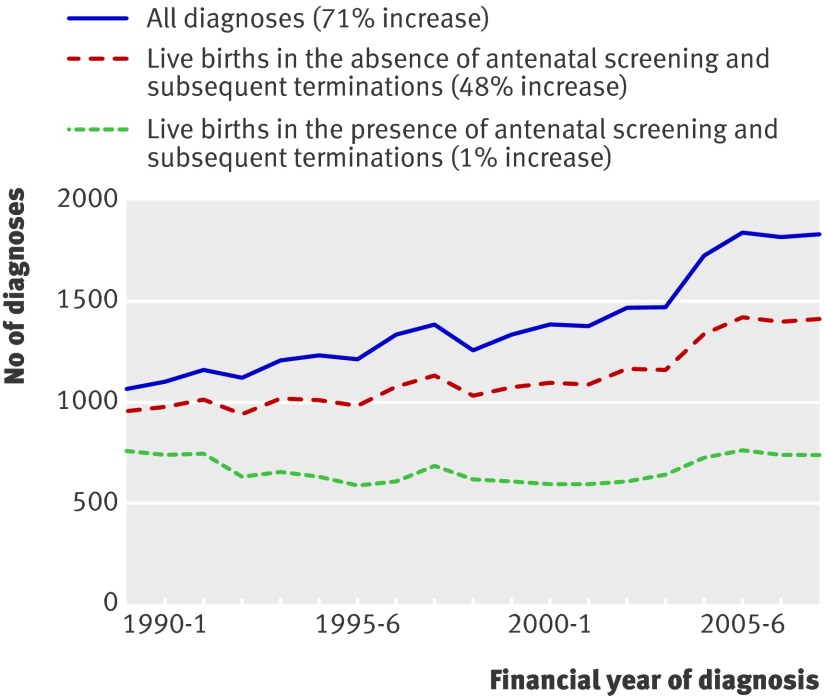

Results Despite the number of births in 1989/90 being similar to that in 2007/8, antenatal and postnatal diagnoses of Down’s syndrome increased by 71% (from 1075 in 1989/90 to 1843 in 2007/8). However, numbers of live births with Down’s syndrome fell by 1% (752 to 743; 1.10 to 1.08 per 1000 births) because of antenatal screening and subsequent terminations. In the absence of such screening, numbers of live births with Down’s syndrome would have increased by 48% (from 959 to 1422), since couples are starting families at an older age. Among mothers aged 37 years and older, a consistent 70% of affected pregnancies were diagnosed antenatally. In younger mothers, the proportions of pregnancies diagnosed antenatally increased from 3% to 43% owing to improvements in the availability and sensitivity of screening tests.

Conclusions Since 1989, expansion of and improvements in antenatal screening have offset an increase in Down’s syndrome resulting from rising maternal age. The proportion of antenatal diagnoses has increased most strikingly in younger women, whereas that in older women has stayed relatively constant. This trend suggests that, even with future improvements in screening, a large number of births with Down’s syndrome are still likely, and that monitoring of the numbers of babies born with Down’s syndrome is essential to ensure adequate provision for their needs.

Introduction

Between 1989 and 2008 two changes occurred that influenced the numbers of diagnosed Down’s syndrome pregnancies, despite no change in the overall number of births in England and Wales. First was the considerable increase in maternal age, which is a major known risk factor for Down’s syndrome.1 2 Second was the increase in antenatal diagnoses of Down’s syndrome, which included non-viable fetuses who would not have survived to term and therefore remained undiagnosed.3

In the early years of the period from 1989 to 2008, the major indication for invasive antenatal diagnosis was a maternal age of 37 years or older. Since the mid-1990s, maternal serum testing and, later, measurement of fetal nuchal translucency, were successful screening tests, and antenatal screening has achieved higher rates of correct predictions and higher coverage year on year. In 2001, the UK National Screening Committee advised that all pregnant mothers should be offered one of the available screening tests for Down’s syndrome, and their recommendations for 2007–10 are that these tests should have a positive rate of less than 3% and a detection rate of more than 75%.4

This report describes the effects of the changes in maternal age and advances in screening on the incidence of live births with Down’s syndrome, and on the number of antenatal diagnoses between 1989 and 2008 in England and Wales.

Methods

Data collected

The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register1 was set up on January 1 1989, and holds anonymous data from all clinical cytogenetic laboratories in England and Wales for more than 26 000 cases of Down’s syndrome diagnosed antenatal or postnatally.5 Almost every baby with clinical features suggesting Down’s syndrome, as well as any antenatal diagnostic sample from a pregnancy suspected to have Down’s syndrome, receives a cytogenetic examination, since the definitive test for the syndrome is detection of an extra chromosome 21 (trisomy 21). All clinical cytogenetic laboratories in England and Wales are asked to submit to the register a completed form for each such diagnosis and its variants. The form contains details of the date, place of, and indications for referral, maternal age, and family history. Most laboratories send a copy of this form to the referring physician for confirmation and completion.

The data have been compared with those from other congenital anomaly registers and those of the UK Office for National Statistics. These comparisons have shown that since its inception the register has captured data for an estimated 93% of all diagnosed births and pregnancy terminations to residents of England and Wales.6 All data are presented by financial year (from April 1 1989 to March 31 2008).

Missing maternal ages

Five per cent of records had missing maternal age, of which more than 95% were postnatal diagnoses. Every case was assigned a set of probabilities of the mother being aged from 15 to 50 years, calculated from the distribution of single years of known maternal ages registered in the same year, matched for antenatal or postnatal diagnoses. The probabilities were then used in any calculations involving maternal age. All women younger than 37 years were classified as younger women and women aged 37 and older as older women for presentation purposes. Age 37 years was chosen as the threshold because at the start of the register, age was used as the initial screening test with many women of this age or older being offered an antenatal diagnostic test before other antenatal screening tests became available.

Adjustment for natural fetal losses

The data included pregnancies that were diagnosed antenatally and subsequently terminated. Many of these pregnancies would not have survived to term and would therefore previously never have been diagnosed (miscarried fetuses are generally not karyotyped). For a comparison of the annual numbers of live births that would have occurred in the absence of antenatal diagnosis and subsequent terminations, adjustment must be made for the risk of a natural miscarriage. To do this, the number of terminations is weighted by the estimated risk of miscarriage, allowing for the fall in risk with increasing gestational maturity and the increase in risk with increasing maternal age.7 For example, at a maternal age of 35 years, only 57% of Down’s syndrome fetuses diagnosed at 13 weeks’ gestation result in a live birth (the others miscarry or are stillborn), so that terminations that occurred at around 13 weeks’ gestation to such mothers are weighted by 0.57 to estimate the numbers of live births that would have occurred at term. This means, for example, that the occurrence of two terminations at 13 weeks to 35 year old mothers is equivalent to around one birth occurring.

Missing outcomes

The outcome of each pregnancy diagnosed antenatally is followed-up, but ascertainment has been slow for certain laboratories in recent years. This is partly because of the increased used of private diagnostic testing, so that the place of testing is not the same as the place of pregnancy outcome. However, the reasons for missing outcomes are unrelated to the actual outcome and to maternal and gestational age in cases subsequently traced. To examine trends in the proportion of women deciding to continue with the pregnancy on receiving a antenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome, we excluded all cases with missing outcomes. To check the validity of doing so, we also examined every year’s outcome data separately, and data from a specific laboratory were included only if outcomes were available for more than 95% of diagnoses. With this smaller dataset, the estimated proportion of women deciding to terminate the pregnancy was the same as that derived from the first method of excluding all cases with missing outcomes, the findings of which are presented in the results.

Results

Trends in diagnoses and live births

The table shows the increase in diagnoses of Down’s syndrome between 1989 and 2008, from 1075 in 1989/90 to 1843 in 2007/8. These values include live births and stillbirths diagnosed postnatally, and outcomes after antenatal diagnoses (terminations, fetal losses, and a small number in which the pregnancy was continued to term). The number of affected live births was 752 in 1989/90 and 743 in 2007/8 (a 1% decrease).

Down’s syndrome diagnoses in England and Wales from 1989/90 to 2007/8 according to year of diagnosis and outcome

| Financial year of diagnosis | Diagnoses | Outcomes of antenatal diagnoses† (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Antenatal | Live births |

Unknown outcomes | Terminations | Miscarriages /stillbirths | Live births | |||

| Reported | Estimated* | ||||||||

| 1989-90 | 1075 | 329 | 752 | 752 | 6 | 93.2 | 2.5 | 4.3 | |

| 1990-1 | 1106 | 386 | 741 | 742 | 14 | 88.4 | 4.3 | 7.3 | |

| 1991-2 | 1168 | 445 | 744 | 745 | 11 | 88.5 | 4.4 | 7.1 | |

| 1992-3 | 1128 | 514 | 625 | 626 | 18 | 92.1 | 3.2 | 4.6 | |

| 1993-4 | 1218 | 595 | 645 | 646 | 11 | 93.2 | 2.1 | 4.8 | |

| 1994-5 | 1234 | 622 | 628 | 629 | 24 | 91.6 | 3.2 | 5.2 | |

| 1995-6 | 1214 | 655 | 582 | 583 | 19 | 91.2 | 2.8 | 6.0 | |

| 1996-7 | 1352 | 758 | 607 | 608 | 17 | 92.7 | 2.8 | 4.5 | |

| 1997-8 | 1395 | 733 | 680 | 682 | 32 | 91.7 | 2.6 | 5.7 | |

| 1998-9 | 1266 | 684 | 610 | 612 | 30 | 91.6 | 2.0 | 6.4 | |

| 1999-00 | 1348 | 765 | 608 | 610 | 38 | 91.9 | 1.9 | 6.2 | |

| 2000-1 | 1387 | 822 | 591 | 595 | 70 | 92.4 | 1.3 | 6.3 | |

| 2001-2 | 1394 | 833 | 588 | 594 | 102 | 91.1 | 2.7 | 6.2 | |

| 2002-3 | 1481 | 908 | 603 | 609 | 106 | 92.4 | 2.1 | 5.5 | |

| 2003-4 | 1476 | 877 | 638 | 643 | 79 | 89.6 | 2.8 | 7.6 | |

| 2004-5 | 1735 | 1039 | 716 | 725 | 143 | 89.8 | 3.8 | 6.4 | |

| 2005-6 | 1843 | 1108 | 746 | 757 | 175 | 91.6 | 2.8 | 5.6 | |

| 2006-7 | 1825 | 1108 | 729 | 740 | 176 | 91.3 | 3.2 | 5.5 | |

| 2007-8 | 1843 | 1112 | 730 | 743 | 214 | 92.8 | 2.5 | 4.8 | |

| Total | 26488 | 14293 | 12563 | 12640 | 1285 | 91.5 | 2.7 | 5.8 | |

*Estimated live births includes 6% of unknown outcomes.

†Calculated as a proportion of all known outcomes.

Around 92% of women who received an antenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome decided to terminate the pregnancy, and this proportion was constant throughout the period covered by the register.

Figure 1 compares the total number of Down’s syndrome diagnoses (top line) with the estimated number of Down’s syndrome live births that would have occurred in the absence of antenatal diagnoses and selective termination (middle line). The two lines differ because some of these pregnancies would have miscarried naturally and not resulted in a live birth. The bottom line gives the estimated number of Down’s syndrome live births that did occur in the presence of antenatal diagnoses and selective termination. The difference between the bottom two lines is attributable to antenatal screening and subsequent terminations, the effects of which have clearly increased over time.

Fig 1 Down’s syndrome diagnoses and live births according to year of diagnosis and presence or absence of antenatal screening and subsequent terminations

Trends in maternal age

The middle line in figure 1 is the number of live births expected in the absence of screening and subsequent terminations; the rise (from 959 in 1989/90 to 1422 in 2007/8) is therefore due to a true increase in the incidence of Down’s syndrome, which can be attributed to the increase in maternal age.

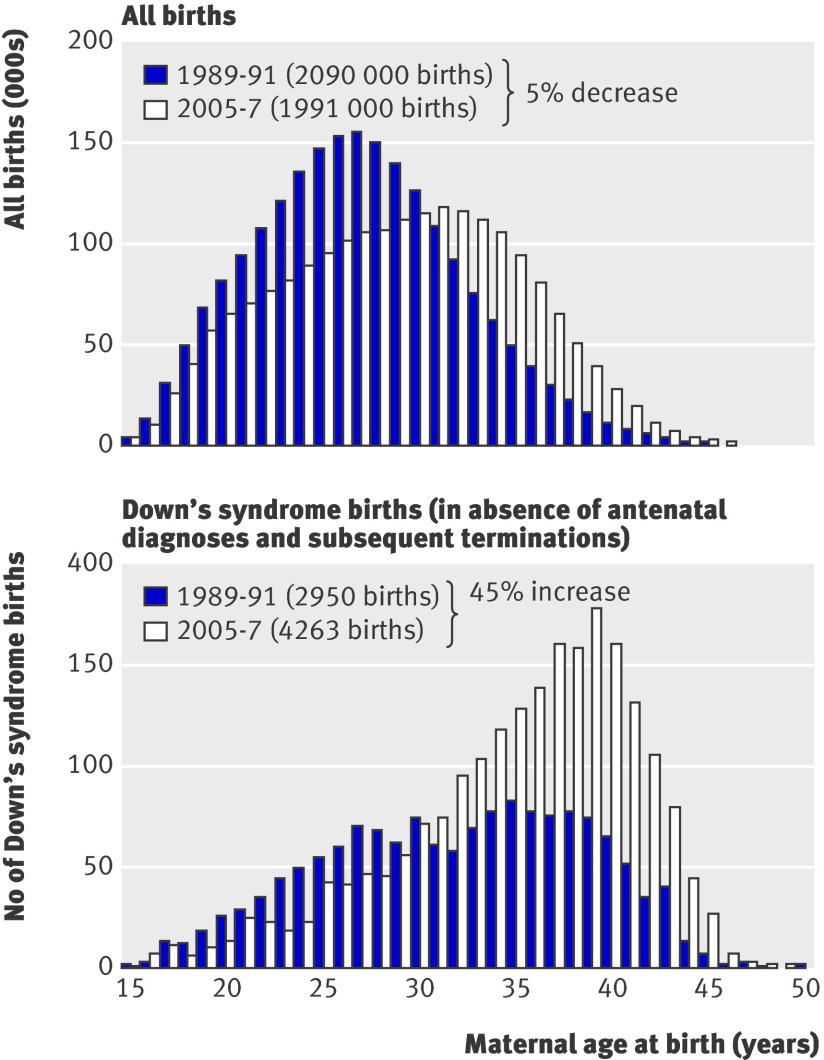

Figure 2a shows the changes in maternal age for all births in England and Wales, and figure 2b shows the consequent effect on Down’s syndrome pregnancies.8 The small increase in the number of older mothers has a large effect on the number of Down’s syndrome pregnancies because the risk of an affected pregnancy is greatly increased for older mothers; the risk for a 40 year-old mother is 16 times that for a 25 year-old mother.

Fig 2 All births and all Down’s syndrome births in England and Wales for 1989-91 compared with 2005-7

Trends in antenatal screening

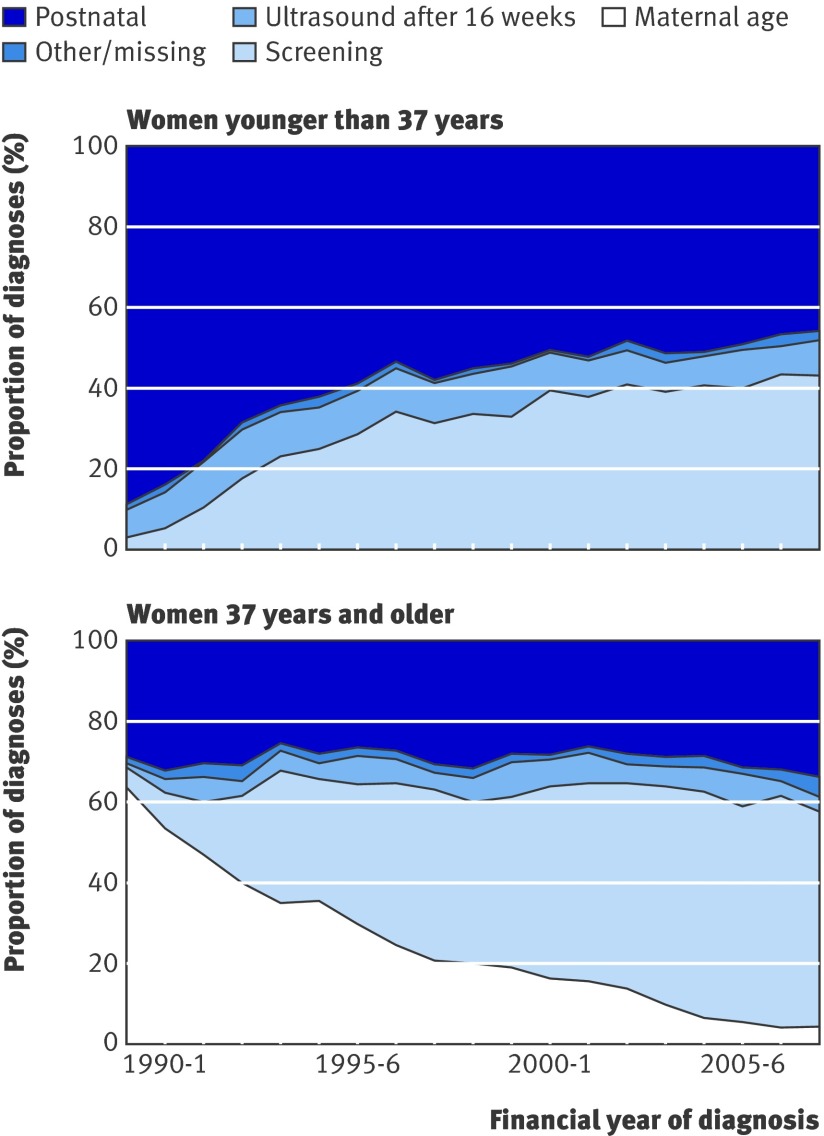

Because maternal age is such a powerful predictor it is the most important element of estimation of risk in all screening programmes. In the early years of the register, maternal age was the only method of screening, and women older than 36 years were offered an amniocentesis. For women younger than 37 years old (fig 3a) few screening tests were available in 1989 and the early 1990s. Antenatal diagnosis was generally done in these women for other reasons, such as a family history of Down’s syndrome, or findings of so-called soft markers at fetal ultrasound examinations, which became more common in the early 1990s. Even when validated screening tests became available, they had lower detection rates in younger than in older women. That the proportion of pregnancies diagnosed antenatally in younger women, which was 3% at the start of the register, began to increase rapidly after about 1993 to around 43% in 2007/8 is therefore unsurprising. Figure 3b shows that the proportion of pregnancies to women of 37 years and older diagnosed antenatally remained at around 70%, with the proportion diagnosed antenatally due to age alone being replaced with diagnoses due to other types of screening.

Fig 3 Reasons for Down’s syndrome diagnoses according to year of diagnosis for women younger than 37 years and women 37 years and older

An important consequence of these changes is that the mean age of mothers of live born children with Down’s syndrome has risen over time, from 30.6 years (sd = 6.1 years) in 1989/90 to 34.4 years (sd = 6.8 years) in 2007/8, while the age of mothers of antenatally diagnosed cases has fallen.

Discussion

We have shown in this paper that the two factors that influence the numbers of live births with Down’s syndrome—the underlying incidence of the syndrome due to the distribution of maternal age, and the numbers of pregnancies that are detected antenatally and subsequently terminated—have changed considerably over the life of the register. Increases in maternal age would have caused a 48% increase in births with Down’s syndrome in the absence of terminations between 1989-91 and 2005-7. However, terminations of Down’s syndrome pregnancies due to an increase and improvements in antenatal screening have caused the number of live births with Down’s syndrome to remain constant.

In older women, a constant proportion of around 70% of diagnoses of Down’s syndrome are antenatal. In the early years of the register, this was because most accepted a diagnostic test because of their advanced maternal age alone, but it is now accounted for by most accepting a diagnostic test due to having had a different screening test.

In younger women, the implementation of more recent methods of screening has had a greater effect, because reasons to offer them diagnostic tests were rare before the availability of these methods, and the earliest screening tests were not very sensitive. By 2007 all women should have been offered screening and the tests available were much improved, with higher detection rates and fewer false positives. Data from the register show that the proportion of antenatal diagnoses in younger women has increased rapidly, but the data shown in figure 3 suggest that this will also plateau at around 70%. In 1992, a prediction was made based on available evidence, that no more than 60% of all women would take up antenatal screening.9 In view of the apparent plateau in uptake of antenatal diagnosis and the increasing maternal age, an increase in the number of affected births was predicted. However this prediction underestimated the future power and effectiveness of new screening techniques. The annual number of Down’s syndrome live births has remained fairly steady as the number of pregnancies terminated balance those resulting from the age-related increase. This plateau will not necessarily remain if maternal age continues to increase and the proportion of parents accepting screening and opting for a termination remains the same or decreases. However, the proportion of women who decide to terminate the pregnancy when they receive an antenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome has remained constant at 92% throughout the life of the register.

The findings also show that parents currently expecting a baby with Down’s syndrome tend to be older than those in previous cohorts, a fact that needs to be considered when planning long term care for those affected. Moreover, such care will need to be extended as life expectancy is probably rising faster in individuals with Down’s syndrome than in others. These concerns might be mitigated somewhat by the much improved educational attainment and social acceptance of people with Down’s syndrome.

The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register is a unique resource that has ascertained over 93% of diagnoses of Down’s syndrome in all of England and Wales over 19 years. It has enabled the effects of changes in screening policies to be accurately monitored. The only other national dataset on this syndrome in England and Wales is that collected by the National Congenital Anomaly System, which is too incomplete to monitor trends.6 10 Regional congenital anomaly registers collect data that enable monitoring of regional trends, but these registers cover only around 55% of all births in England and 100% of all births in Wales.10 The main current weakness of the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register is the necessity to estimate the number of live births, because of largely administrative delays in receiving data for some pregnancy outcomes after an antenatal diagnosis. However, these delays are unrelated to the outcome in cases that we have subsequently managed to trace, and we are finding that with increased resources cases are often traceable.

Other countries have reported similar trends in Down’s syndrome diagnoses, screening, and subsequent live births, generally by merging their birth registries with data from cytogenetic laboratories.11 12 13 14 15 The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register covers a greater population (all of England and Wales) and a longer period of changing diagnostic technologies than do registers from other countries.

In conclusion, dramatic changes in demography have been offset by improved medical technology and have resulted in no substantial changes in the birth prevalence of this quite disabling condition. Despite these underlying changes, it is striking that for women older than 36 years with a Down’s syndrome pregnancy, the proportion who have had an antenatal diagnosis has remained constant at 70%, and for all women with an antenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome the proportion who decide to terminate the pregnancy has remained constant at 92%. These findings indicate that even with improved screening tests, a considerable proportion of women may still decide not to be screened, and a qualitative study investigating why some women decide not to be screened would be valuable. To ascertain whether the decision is an informed one and, if not, to address the lack of information, is important. Knowledge about how much the risk of fetal loss after amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling influences the decision to have a diagnostic test would help us to predict the impact of the future introduction of non-invasive diagnostic tests. The lack of iatrogenic risk may result in a higher uptake than current diagnostic tests, which would reduce, or even abolish, invasive diagnostic tests, and could substantially increase the numbers of therapeutic abortions of affected fetuses at an earlier gestational age.16 These future changes need to be closely monitored to ensure that appropriate resources are available both for the potentially increasing numbers of therapeutic abortions and also for the babies who will still be born with Down’s syndrome.

What is already known on this topic

Older mothers are at increased risk of having babies with Down’s syndrome.

Antenatal screening for Down’s syndrome is more available now than in the early 1990s.

What this paper adds

The number of diagnoses of Down’s syndrome has increased by 71% (from 1075 in 1989/90 to 1843 in 2007/08), whereas that of live births decreased by 1% (755 to 743), owing to antenatal screening and subsequent terminations.

In the absence of antenatal screening and subsequent terminations, the numbers of Down’s syndrome births would have increased by 48% due to parents choosing to start families later.

Contributors: JM is Director of the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register and is responsible for the data and the analysis presented and worked jointly with EA in the writing of this paper. Haiyan Wu, Annabelle Stapleton, and Khadeeja Wahid maintain the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register database. JM is the guarantor for the study.

Funding: The NHS Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme funded the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register to collect the data until March 2009. The funders played no role in the analysis or write up of this paper. JM and EA are independent of the Fetal Anomaly Screening Programme. JM and EA had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data sharing: no additional data available.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register (as part of the British Isles Network of Congenital Anomaly Registers) has multicentre research ethics committee approval from Trent MREC. It was granted section 60 class support under the Health and Social Care Act 2001 for the collection of personal information without consent.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3794

References

- 1.Morris JK, Mutton DE, Alberman E. Revised estimates of the maternal age specific live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome. J Med Screen 2002;9:2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuckle HS, Wald NJ, Thompson SG. Estimating a woman’s risk of having a pregnancy associated with Down’s syndrome using her age and serum alpha-feto protein level. Br J Obst Gynaecol 1987;94:387-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberman E, Mutton D, Ide R, Nicholson A, Bobrow M. Down’s syndrome births and pregnancy terminations in 1989 to 1993: preliminary findings. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK National Screening Committee. Fetal anomaly screening programme—screening for Down’s syndrome: UK NSC policy recommendations 2007-2010: model of best practice. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_084732.

- 5.Mutton DE, Alberman E, Ide R, Bobrow M. Results of first year (1989) of a national register of Down’s syndrome in England and Wales. BMJ 1991;303:1295-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savva GM, Morris JK. Ascertainment and accuracy of Down syndrome cases reported in congenital anomaly registers in England and Wales. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2009;94:F23-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savva GM, Morris JK, Mutton DE, Alberman E. Maternal age-specific fetal loss rates in Down syndrome pregnancies. Prenat Diagn 2006;26:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birth Statistics. Office for National Statistics FM1 18-20;34-6.

- 9.Nicholson A, Alberman E. Prediction of the number of Down’s syndrome infants to be born in England and Wales up to the year 2000 and their likely survival rates. J Intellect Disabil Res 1992;36:505-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd PA, Armstrong B, Dolk H, et al. Congenital anomaly surveillance in England—ascertainment deficiencies in the national system. BMJ 2005;330:27-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iliyasu Z, Gilmour WH, Stone DH. Prevalence of Down syndrome in Glasgow, 1980-96—the growing impact of prenatal diagnosis on younger mothers. Health Bull (Edinb) 2002;60:20-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melve KK, Lie RT, Skjaerven R, Van Der Hagen CB, Gradek GA, Jonsrud C, Braathen GJ, Irgens LM. Registration of Down syndrome in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway: validity and time trends. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:824-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins VR, Muggli EE, Riley M, Palma S, Halliday JL. Is Down syndrome a disappearing birth defect? J Pediatr 2008;152:20-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekelund CK, Jorgensen FS, Petersen OB, Sundberg K, Tabor A. Impact of a new national screening policy for Down’s syndrome in Denmark: population based cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siffel C, Correa A, Cragan J, Alverson CJ. Prenatal diagnosis, pregnancy terminations and prevalence of Down syndrome in Atlanta. Birth defects research 2004;70:565-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo YM, Tsui NB, Chiu RW, Lau TK, Leung TN, Heung MM, et al. Plasma placental RNA allelic ratio permits noninvasive prenatal chromosomal aneuploidy detection. Nat Med 2007;13:218-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]